In the fall of 2003, saxophonist Branford Marsalis released his CD Romare Bearden Revealed. The project was suggested by Robert O’Meally for the occasion of the major retrospective, The Art of Romare Bearden, which opened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in September 2003 and later toured to San Francisco, New York, and Atlanta. Originally, the plan had been to put together an anthology of historical jazz performances by artists connected with Bearden’s work. Yet in the end this idea was replaced with a newly recorded CD by Branford Marsalis’s quartet that featured several special guests, including the rest of the Marsalis family and Harry Connick Jr.

According to O’Meally’s liner notes for the CD, Marsalis’s recording can be read as “part of a jam session in which Romare Bearden’s paintings play a vibrant part: the musicians playing the paintings of a visual artist who had a mighty brush with the blues.”1 Indeed, Marsalis’s record marks a fascinating moment of transmedial, synesthetic dialogue between visual art and music. It is fascinating because the often-proclaimed influence of jazz and blues on Bearden’s work here comes full circle. Now it is the musicians who claim their music is influenced by the painter who is said to be influenced by the music. However, this very circular structure raises some fundamental questions about the nature of this influence, questions that have rarely been asked from a theoretical point of view. For what we hear on Marsalis’s record is (not surprisingly) nothing but jazz. Where is Romare Bearden in this music, we may ask, other than on the cover and in the booklet? And if this question is asked, we also have to wonder about its flipside: where exactly do we locate jazz in Bearden’s paintings?

The answer typically given in the literature on Bearden has been to single out structural and formal equivalences in jazz and Bearden’s collage paintings.2 The most frequent reference in this respect points to Bearden’s conversations with Stuart Davis. It was Davis who suggested that Bearden listen to Earl “Fatha” Hines in order to gain a fuller understanding of the importance of space. Bearden himself stressed the importance of Davis’s advice: “Some years ago,” he wrote in 1987, “I showed a watercolor to Stuart Davis, and he pointed out that I had treated both the left and right sides of the painting in exactly the same way. After that, at Davis’s suggestion, I listened for hours to recordings of Earl Hines at the piano. Finally, I was able to concentrate on the silences between the notes. I found that this was very helpful to me in the transmutation of sound into colors and in the placement of objects in my paintings and collages.”3

Bearden’s likening of musical space—which is itself a metaphor taken from the realm of the visual—to visual space is of course a problematic one. Taken literally, he confounds two different modes of aesthetic reception, namely, listening to music, which is bound primarily to time—to the diachronic, we might say—and looking at an image, which is fundamentally based on space, on the synchronic. While it will be important to consider how Bearden works at bringing together time and space, the uncritical equation of Hines’s musical space and Bearden’s visual space only makes sense on a loose metaphorical level. Davis suggested yet another analogy that seems to solve the problem of the incommensurability of the spatial and the temporal by looking at music in synchronic terms. He pointed out not only the silences in Hines’s solos, but also his intervals, explaining to Bearden: “The interval is what you leave out.”4

This statement, however, opens up even more problems. How can we think of intervals in terms of leaving things out? According to this logic, wouldn’t we have to say that musicians “leave out” more when they play a fifth rather than a third, and thus create more space? Strictly speaking, this only makes sense if one considers the intervals not as the organization of sound but as the different keys pressed down on the piano. In other words, even when Davis conceptualizes music in synchronic terms through the interval, this does not really lead him to the dimension of space.

Despite its vagueness, many critics have used the rhetoric of equivalence to claim direct links between the paintings and the music. This eventually ended in sweeping claims of Bearden painting jazz.5 For instance, in 1987 a local paper’s review of a show in Hartford, Connecticut, carried the headline: “In Innovative Exhibit, Bearden Executes Jazz on Canvas.”6 Similarly, Myron Schwartzman, whose Romare Bearden: His Life and Art (1990) is considered the authoritative biography of Bearden, notes in a different book (Romare Bearden: Celebrating the Victory, 1999) written specifically for a young audience:

Romare Bearden made his art sing on canvas. He created the visual definition of jazz, as if he played the red-hot brassy ragtime figures of a great trumpet player, or the oh-so-cool blue, elegantly composed chords of a piano legend. Just as the great blues-band sections call and answer each other, trading “riffs” or musical phrases with each new line of blues, so Bearden called and recalled his life experiences in his art.7

There is one major problem that such claims run into: a purely formalist analysis leaves no room for the dimension of aesthetic experience. In other words, the viewer is left out of the description, just as the listener is excluded. Saying that Bearden painted jazz—and trying to prove this by pointing out structural and formal similarities—glosses over the peculiarities of the aesthetic experiences of music and painting. In this sense, these hasty conclusions omit what really counts in an intermedial endeavor. The tacit assumption behind the above claims is not only that Bearden painted in the way a jazz musician plays but that we as viewers and listeners have some of the same experiences in listening and viewing. But by simply analyzing the formal dimension of the works in their respective medium, this assumption is not at all interrogated.

What I propose to turn to, then, are some basic insights gained by reception aesthetics in the last three decades. Wolfgang Iser’s contribution to literary theory has developed around such key terms as the “implied reader” and “blanks” that are filled by the reader. In short, in a literary work we have to take account of the reader’s contribution to the aesthetic experience: the reader is obliged to bring something of himself or herself to the act of reading in order to experience the literary work. This becomes plausible at once when we consider that we never really know a character in a literary work. When we visualize a literary figure, we add our own imaginary portions to what is provided in the text in order to construct a coherent figure that we think we understand and know.8 At the same time, reception aesthetics stresses the formal features of the work in their capacity to direct the reader’s actualization of the text. This is the main function of the blank: it suspends a relationship—a connectivity, to use Iser’s term—between certain elements of a work. These relationships are then established by the reader. In this sense, the positioning of the blanks and the choice of elements affected by the suspension of connectivity all direct the reader to his or her site of activity. Yet the precise qualities of the relations that the reader will provide differ from case to case.

Several art historians, most notably Wolfgang Kemp, have successfully applied Iser’s thoughts to the visual arts, thinking about the viewer who is “inside” the painting as an “implied beholder.”9 It is important to note that the premier example of reception aesthetics within art history seems to be history painting. The reason is the common practice in history painting of referring to a historical or mythical narrative that is intelligible to the viewer as he or she is confronted with the painting. Thus, on the one hand constitutive blanks are filled in by the viewer on the basis of a familiar narrative; on the other hand, the painter’s evocation of such a narrative as a device of interplay between text and context still leaves open myriad ways for the engagement of the beholder. This emphasis of narrative and the evocation of the culturally familiar will concern us later, since these are key strategies of Bearden’s approach.

First, however, we have to note that Bearden himself in many ways directed his aesthetic approach in terms quite similar to how reception aesthetics proposes to proceed in analyzing art. Bearden talked about his various influences at length, including jazz, cubism, and the Flemish masters. He pointed out repeatedly his interest in how these artists found ways to engage the beholder. In his essay “Rectangular Structure in My Montage Paintings” he writes, “I have incorporated techniques of the camera eye and the documentary film to, in some measure, personally involve the onlooker.”10 In the same article, he becomes very specific about his interest in Chinese landscape painting. At the end of the 1940s he had found a new mentor with whom he studied, one Mr. Wu. He attributed to his study of Chinese landscape the concept of a path of entry, which he explained as “the device of the open corner to allow the observer a starting point in encompassing the entire painting.”11 In other words: Bearden was centrally concerned with how to direct the onlooker’s gaze and how to spatially structure the painting according to the needs of this directing. This explains his interest in space much more directly than his connection with jazz. The organization of the image in terms of space was crucial to the way the onlooker would perceive the painting. Writing again on Chinese landscape painting, Bearden explains: “By searching out rhythmical movements in rocks, mountains and clouds, the painter followed what he believed to be the way of nature…. Space is allembracing; it is … dynamic.”12 If space is dynamic and rhythmical, this is, again, not only a statement on the object level of a painting. Rather, it precisely relates to the way the onlooker is directed in looking at the picture. It is as if the viewer’s look were traveling across the picture plane, directed by the various shapes and their relation to each other, at times speeding up, at other times coming to a halt.

Here we come to an understanding of the way in which time and space work together in Bearden’s collage paintings. There is indeed a diachronic dimension to the aesthetic experience of a painting, something we might call a rhythm. In a letter from 1945, Bearden explained this himself: “I’m beginning to see what time sense means in a picture…. I’m trying to get things held together, but lead the eye from section to section—taking the time say as music does—a composition extended in time.”13

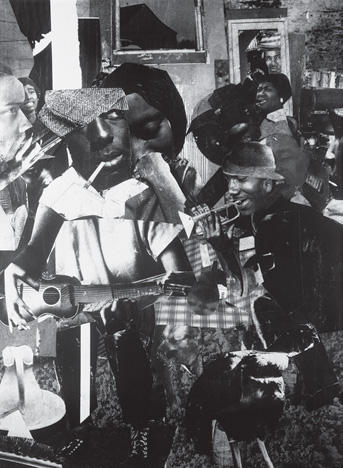

We can observe this when we look at a collage such as the 1964 Train Whistle Blues, No. 2, which became part of the series Projections. The actual collage was rather small, roughly eleven by fourteen inches. For Projections, Bearden blew up the original to a wallpaper format using photostat technology, thereby transforming the color collage into black and white (Figure 9.1). As noted above, it remains impossible to predict precisely how the onlooker will interact with the structure of the image. Yet the formal features of Train Whistle Blues, No. 2 allow us to make assumptions about likely processes of actualization. As in most collages of the series, portions of faces take a central position and attract primary attention. Here, the viewer’s gaze will most likely focus first on the face that belongs to the guitar player—simply because this element of the picture, due to its size and coherence, is most easily discernible. From here the course of the onlooker across the picture is difficult to foretell, although it seems likely that the viewer will follow the direction of the guitar player’s gaze to the right. More important, and fully in line with the modernist conventions of the collage, the viewer will soon be struck by the uneven ratios and perspectives of the various elements that make up the assembled figural entities of the collage. Moreover, in order to complete those entities that form a whole only at second glance—like the guitar player, whose firm stand on the dark rug comes almost as a surprise due to the tonal contrast of upper and lower body—the onlooker must adjust the pace of his or her gaze. In turn, new ensembles open up, as, for instance, the contiguity of the trumpet’s bell and the guitar player’s lower sleeve, which form a quasi-triangular pair. In short, there is a rhythm in observing Train Whistle Blues, No. 2, and, in combination with the thematic conspicuousness of musicians and instruments, this may be one reason why many critics are eager to align Bearden’s works with jazz.

Figure 9.1 Romare Bearden, Train Whistle Blues, No. 2. 1964. From the Projections series. Photomontage, 39¼ in. × 29½ in.© Romare Bearden Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2007. Courtesy of ACA Galleries, New York.

But it would be easy to overstate the pertinence of such an analogy. Slowing down and speeding up—tempo rubato—is much too general a musical device to enlist it as proof for specific intermedial connections between Bearden’s art and jazz. One could even argue that tempo changes are far less typical of African American music than a steady pulse (the apposite analogy would rather have to point to the practice of playing behind and ahead of the beat). In any case, tempo and rhythm open up merely first gateways to a conjunction of painting and music in the viewer’s experience. For a more complex account, we also have to consider Bearden’s extensive use of narrative. However, narrative is often regarded as incommensurable with the autonomous aesthetic of modernism. This becomes obvious when we read Albert Murray’s comments on Bearden’s art. Murray and Bearden became friends when they met in Paris in the 1950s. Later Murray worked as Bearden’s literary adviser and contributed titles for some paintings as well as captions. In his essay “Bearden Plays Bearden,” Murray attempts to downplay the narrative element of Bearden’s work in order to stress the equivalences of jazz and the collages on a formal level. He begins his argument by establishing aesthetic (formal) links at the expense of a more representational axis (here, somewhat confusingly, called “forms”):

The specific forms as such—however suggestive of persons, places, and things and even of situations and events, actual or mythological—are by [Bearden’s] own carefully considered account always far more a matter of on-the-spot improvisation or impromptu invention not unlike that of the jazz musician than of representation such as is the stock in trade of the portrait painter, the illustrator, and the landscape artist of, say, the Hudson River School.14

Murray makes two claims at once. On one level he says that in Bearden’s own account specific forms are subordinate to their improvisational genesis. Of course, all we can see in the painting are forms—representational and abstract ones—but we can never see the actual act of improvisation by the artist. Murray, I think, is aware of this and tacitly mixes this hierarchy (in which process ranks higher than form) with a second hierarchy, namely, abstraction versus narration. This explains why, in belittling form as compared with process, he singles out representational forms—“however suggestive of persons, places, and things and even of situations and events, actual or mythological.” Thus, while Murray’s argument actually requires the proof that Bearden’s art is process oriented and is, in that sense, much like the improvisation of a jazz musician, he ends up devaluing both the representational and narrative elements of Bearden’s work in order to stress the equivalences of jazz and the collages as process. Because the viewer cannot witness the actual act of painting, what the emphasis on process entails is a downplaying of the representational meaning of figural shapes. To look at a painting as an improvisational process, then, means treating figural shapes as abstract ones, as well as pushing the narrative dimension to the background. Murray writes, “In the case of Farewell Eugene, Bearden tells a touching and informative anecdote about a boyhood friend in Pittsburgh and about how Eugene, who taught him how to draw, used to make pictures of houses in which the interior activities could be seen from the street. But the painting does not tell that story at all!”15

Murray’s remark is really quite ironic. Farewell Eugene is part of an autobiographical series from 1978, entitled Profiles/Part I: The Twenties. One special feature of the show was the captions that accompanied each collage. These captions—single sentences—were written in chalk directly onto the gallery’s walls.16 And it was Murray himself who wrote, or at least co-wrote, these texts. The caption about Eugene reads: “The sporting people were allowed to come but they had to stand on the far right.” Eugene, whom Bearden has called his first artistic inspiration, died as a teenager; thus the line and the representational elements of the painting refer to his funeral. Murray is right, then: the painting does not tell the story. And neither does the autobiographical line do so. But the sentence—as well as the title—nevertheless relates to the representational level of the painting and adds a fraction of the story. It serves a narrative purpose similar to that of common historical knowledge for history painting: it gives the viewer a necessary dimension to engage in the aesthetic experience of constructing relationships between the elements that are given and those that are omitted.

What we begin to see here is that Murray’s claim of Bearden having privileged improvisational process over the representational and thus the narrative is deeply problematic. Various letters from the 1940s and 1950s to artist colleagues like Walter Quirt and Carl Holty make clear that he conceptualized both aspects in balance. In his 1969 article “Rectangular Structure in My Montage Paintings” he comments: “I do not burden myself with the need for complete abstraction or absolute formal purity but I do want my language to be strict and classical, in the manner of the great Benin heads.”17 It comes as no surprise, then, that the important narrative function in his work stirred the interest of playwright August Wilson. Wilson never met Bearden but, having come across his two autobiographical series (the already-mentioned Profiles/Part I: The Twenties and Profiles/Part II: The Thirties), he used one painting of each series as the source for plays. He based Joe Turner’s Come and Gone on Bearden’s Mill Hand’s Lunch Bucket, and he wrote a play called The Piano Lesson inspired by Bearden’s collage of the same title. This is not to suggest that “Wilson wrote Bearden” any more than “Bearden painted jazz” or “musicians played Bearden”; but it demonstrates the importance of narrative for transmedial transformation.

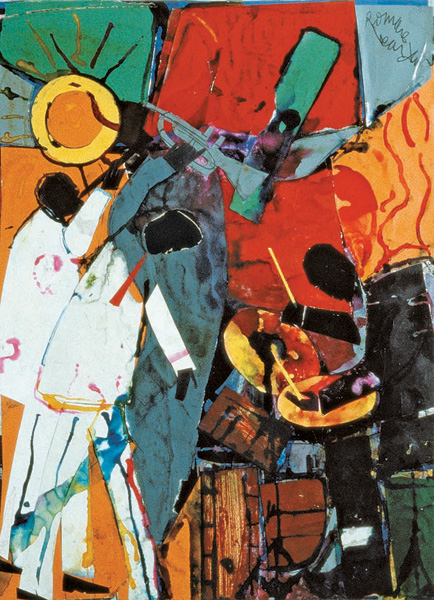

When we look at a collage painting like Drum Chorus from 1986, we can see how narrative, representational, and abstract elements interact to produce a specific aesthetic experience (Figure 9.2). As in Train Whistle Blues, No. 2, the path of entry is afforded by the representational elements of the painting, namely, the three musicians. These figures also provide the frame on the left and the right, as the bodies of the musicians lean inward.

But the longer we look, the more our attention shifts from the representational level to that of forms, shapes, and planes. We begin to put the central red plane in relation to the green, orange, and white on the left, and the blue, orange, black, and green on the right, subdividing the painting into a roughly rectangular structure that increasingly loses its order as we move toward the lower center. Even the very spaces that at first struck the viewer as representational now become recoded in terms of shape and color and eventually may take on a different representational meaning. This concerns, for instance, the heads of two of the musicians. When we integrate the main two colors in the center—the grayish blue and the red—into a single shape, we see how they are held together symmetrically by the inward-leaning heads of the musicians. Yet the initial representational level is never quite superseded.

Thus we arrive at an experience of the painting that creates new relations between the scene represented here (three musicians, two of whom are playing), the implication of the title that the scene is a drum solo, and the non-figurative dimensions of the painting. In other words, the abstract and the figurative start to interact: “Blues and the Abstract Truth,” we might say, following Oliver Nelson.18

Figure 9.2 Romare Bearden, Drum Chorus. 1986. Collage and watercolor on board, 16⅝ in. × 12⅛ in. © Romare Bearden Foundation VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2007. Courtesy of the Bearden Foundation.

Following this interaction, we can highlight the contrast between the drummer and his drum set as that section of the painting that comprises the highest density of small forms in dark earthy colors, and, on the other hand, the large red plane in the center, which seems to radiate from the cymbals. But can we deduce from this visual contrast how the viewer will imagine the music played by Bearden’s musicians? I think it would be naïve to think that upon seeing Bearden’s picture the viewer feels compelled to imagine a concrete sound at all. But if one were to infer an imaginary sound from Drum Chorus in order to argue for Bearden’s close links to jazz, it would not suffice to say that Bearden’s treatment of colors and shapes is somehow jazzy. Rather, one would have to claim, for instance, that the visual contrast between the jumbled quality of the drummer-cum-drum set and the relatively steady organization of the red plane can be translated into a musical imagining, in which the immediate rumbling activity of the drummer flows into an atmosphere of sound—a sheet of sound, as it were—that is larger and steadier than the drummer’s individual beats. Of course I am not at all saying that every viewer will actualize the painting in such a way. What I am rather saying is that if we want to claim that the viewer experiences something like jazz when looking at Drum Chorus, it seems most accurate to me to use such a theoretical construction to explain it.

But construing the sound of Drum Chorus from the formal determinants of the picture remains culturally hollow as long as one neglects how narrative enters into the aesthetic experience of the painting. It might at first seem that we are not interested in a narrative in Drum Chorus, beyond the fact that there are three musicians playing. But it is of course crucial that Bearden’s musicians are black musicians. While Albert Murray is right in saying that this blackness is not representational in a mimetic sense, it surely is also not a purely formal consideration; it is iconic in the sense that it activates cultural constructions of African American culture. Bearden habitually uses iconic signs—marked self-referentially as symbols rather than truly mimetic signs—to call upon these cultural associations. In Drum Chorus, for instance, this explains the function of the circular shape in the upper left corner, which I interpret as both a spotlight and a sun.19 (The spotlight/sun also clearly fulfills an abstract function, its orange inner circle providing a counterweight to the orange rectangle it tangentially touches.) Again, this ties in with my discussion about the representational and the abstract, for this iconic dimension of the black musician enters into a dialogue between what Lisa Kennedy has called “the black familiar” and Bearden’s aesthetics of defamiliarization, which serves the distinct purpose of opening up the in-between.20 The interplay between representation and form, then, always takes place in the realm where representation carries the meaning of culturally constituted signification, while also performing this very cultural constitution. Not surprisingly, one of Bearden’s most overtly political moves has been to combine iconic and narrative means, for instance in reinterpreting Homer’s Iliad (1948) and Odyssey (1977) through the lens of black iconography, such as trains, record players, quilts, and, of course, musicians. Thus, when we engage in the interplay of Bearden’s representation of jazz musicians and the abstract forms of which they consist and by which they are surrounded, we cannot help but pursue this inside the strictures of the cultural codes of blackness. The crucial point here is to remember that Bearden uses specific iconic means to evoke these cultural narratives, and without them any link to jazz or African American culture more generally would seem far-fetched.

The reason I have pursued an analysis of Drum Chorus at some length here is that it also plays a role in Branford Marsalis’s Romare Bearden Revealed. The reference is somewhat oblique, however. In the booklet, the painting is reproduced at stamp size along with several other works. In his notes on the tune “Laughin’ & Talkin’ (with Higg),” Robert O’Meally first quotes Branford Marsalis at length. The piece was recorded with a quartet: drums, bass, trumpet, and saxophone, no piano. Hence, Marsalis points out the tune’s adventurous sound and continues: “That’s Romare: adventurous.” Marsalis then makes a leap to pointing out the subject matter of drummers in Romare Bearden’s paintings: “And in his work you just see all those drummers, drummers everywhere.” This is O’Meally’s cue for establishing a link between “Laughin’ & Talkin’ ” and Drum Chorus: “See Bearden’s Drum Chorus—with testifying horns and with drummer’s sticks that could be a conductor’s batons, writer’s tools, or swinging artist’s brushes.” In other words, having introduced the subject matter of drums with Marsalis’s quote, O’Meally creates the intermedial connection through the representational level—the various possibilities of reading the drummer’s sticks—implying that the drummer we see here is a synecdoche for a certain kind of artist. It is clear that Bearden belongs to this specific kind of artist: he is the swinging artist whose brushes O’Meally detects in the painting. But if the whole challenge of these liner notes—written, as they are, for a general audience interested in both jazz and painting—is to make clear why Bearden’s paintings are swinging and are an inspiration for Marsalis, we end up with a tautology: the painting swings because in it we see a kind of artist who is swinging. And the depicted artist is swinging because his creator, Bearden, is a swinging artist too.

“Laughin’ & Talkin’ ” itself, however, does not really pick up on the representational level of the painting. The recording is far from being a feature number for the drummer (although drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts is the composer, and, as the title implies, the composition is presumably a dedication to his late colleague, drummer Billy Higgins). Placed at the center of the recorded rendition is the dialogue between Branford and his brother Wynton—and, secondarily, their respective interaction with Watts. One wonders, then, whether matching this painting with this recording was not actually a rather random choice. In what sense is “Laughin’ & Talkin’ (with Higg)” revealing Romare Bearden differently than any other jazz recording would have done?

Considering my previous discussion on the issue of reception aesthetics, the connection between “Laughin’ & Talkin’ ” and Drum Chorus must remain elusive because it fails to address some of the most vital questions about the link across the different media: what could a thorough engagement of jazz musicians with Bearden’s paintings sound like? How can the aesthetic experience of looking at Bearden’s art be translated—and here I do not simply mean finding an equivalent—into an aesthetic experience in the medium of music? And more specifically, how can the imaginary listening that is made possible through the painting’s interaction of representational and abstract aspects be translated not only into real music but also into an imaginary viewing as a result of the aesthetic experience of listening? In asking these questions, I do not want to blame the musicians for having evaded a profound engagement with visual art. Marsalis may have decided early on, and for good reasons, that the music would have suffered from a forced linkage of music and painting. One might simply have to admit that when it comes to playing jazz, the influence of visual art remains an intangible inspiration at best. The problem is that the discourse surrounding a CD like Romare Bearden Revealed does not seem to allow for an open confrontation with its own conceptual limits.

“Laughin’ & Talkin’ ” is not the only track on the CD in which there is little serious engagement with what the project claims to be about. Nevertheless, this selection occupies an exceptional place on Romare Bearden Revealed, because nowhere does the connection between the two media remain as open as here. Most tracks establish a link to Bearden’s art by re-appropriating titles: the musicians mostly play compositions whose titles Bearden had borrowed for his paintings. However, this kind of link proves to be an evasion of the transmedial connection. Going back to the original musical reference of the paintings means almost undoing Bearden’s criss-crossing. For instance, Marsalis has selected “Carolina Shout,” the well-known stride piano piece by James P. Johnson, which also provided the title to one of the collage paintings of Bearden’s series Of The Blues (1974–75) (see Figure 8.1). On the record, “Carolina Shout” is featured in a stunningly traditional rendition performed by Branford and guest pianist Harry Connick Jr. The established connectivity by the musicians thus highlights the intra-musical dimension, in fact precluding an engagement with the painting, even though O’Meally claims to have found such an engagement by emphasizing the double meaning of the shout as a coming together of body and soul. But if this is perceivable in the painting and the tune, we would at least have to admit that the merging of body and soul is a prominent feature of virtually all successful jazz.

Yet another example of the attempt to establish a connection via the title is “I’m Slappin’ Seventh Avenue.” Bearden named one of his collages after this tune by Duke Ellington, which was written “for the 1938 Cotton Club Revue as a feature for tap dancer Peg Leg Bates,” as O’Meally tells us in the liner notes. Bearden’s painting from 1981 is a collage that importantly brings together icons from different eras, such as a car from the 1970s and a man dressed in suit and hat, carrying a cane. But the entry of the musicians into the dialogue with Bearden eschews a detailed engagement with the painting; instead, they focus on the intra-musical connection with Ellington. Consequently, O’Meally is forced to establish the link between Bearden’s I’m Slappin’ Seventh Avenue and Marsalis’s rendition thereof in general terms of style: “Works by both Bearden and Marsalis bespeak high-fashion, Harlem-style.”

More productive is the strategy we find in “B’s Paris Blues.” The composition refers to Bearden’s painting Paris Blues, which itself seems to refer to Michael Ritt’s 1961 movie Paris Blues, featuring Louis Armstrong, who is depicted in Bearden’s painting along with Ellington and an African mask. The slight alteration in the new composition’s title provides us with a bit of biographical and anecdotal information on Bearden. Bearden himself spent time in Paris in the 1950s and he has told the story of dropping in at a private party where Sidney Bechet was playing.21 Hence, the “B” of “B’s Paris Blues” refers to both Bearden and Bechet. This we understand because Marsalis’s rendition of the tune on soprano saxophone is an obvious homage to Bechet. With this move, the tune becomes something like biographical “history music,” not unlike Bearden’s own biographical series Profiles/Part I and Profiles/Part II. While the reference remains essentially musical, the biographical clue gives us a chance to listen to the soprano sax not only with the imaginary complementation of Bechet but also of Bearden in Paris.

If “B’s Paris Blues” is more convincing in crossing from music to painting than the selections discussed previously, Doug Wamble’s composition “Autumn Lamp” may at last come close to fulfilling the promise of “revealing Romare Bearden.” Wamble, a guitar player and singer who has musical roots not only in jazz but also in blues, country, and folk, took his inspiration from Bearden’s 1983 collage Autumn Lamp (Guitar Player) (Figure 9.3). Here the sharing of titles does not merely lead back to an intra-musical reference, although there is that too: Wamble evokes the slide technique of guitar players like Mississippi Fred McDowell and Blind Willie Johnson, both of whom have recorded the spiritual “Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning,” which may thus be the common reference point for both Bearden and Wamble. But beyond uncovering Bearden’s possible reference, Wamble engages with the representational dimension of the painting. It is as if Wamble, in the course of his solo rendition of a country blues, becomes the embodiment of Bearden’s guitar player, who, ironically, is not even playing in the picture. Bearden makes the body of the guitar look battered and the strings torn: a visual effect achieved through collage, which Wamble translates into sound by stretching—literally: sliding—the intonation to its limits. O’Meally’s liner notes attempt to establish the link between the music and painting through the improvisational character that supposedly informs both. Yet Wamble’s rendition of a slow country-inflected blues theme works well not because there is much room for improvisation but because Wamble makes extended use of rubato. In this particular case, this is, in fact, the decisive technique for attaching sound to image, because the floating tempo changes so characteristic of country bluesmen accompanying themselves on guitar rely on the musician being a solo performer. As soon as a rhythm section is added, time keeping becomes indispensable. In other words, Wamble’s rubato symbolically underlines his being on his own.

Figure 9.3 Romare Bearden, Autumn Lamp (Guitar Player). 1983. From the Mecklenburg Autumn series. Oil with collage, 40 in. × 31 in. © Romare Bearden Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2007.

But Bearden’s guitar player also exceeds the cliché of the alienated traveling blues man of the post-Reconstruction South and in this regard becomes more difficult to capture for Wamble. Bearden gives his guitar player the expression of a contented, confident, and peaceful individual—his hands rest complacently in his lap—who looks at the viewer with remarkable openness, his smiling face slightly tilted to the side. This blues man betrays not the least bit of the vulnerable self-assertiveness typically associated with blues singers battling a host of social pressures. The lamp, as much a symbol of rusticity as of security and hope, underlines the guitar player’s languorous ease. As Mississippi Fred McDowell and Annie Mae McDowell sing in the chorus of “Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning”: “Now here don’t you get worried / See what the Lord has done.”22 Doug Wamble’s decision to avoid any of the conventions of blues lyrics by not singing at all may be the most effective and unobtrusive way of acknowledging Bearden’s deviation from the blues singer’s stereotypes.

But since “B’s Paris Blues” and “Autumn Lamp” will have to count as exceptions to the rule, we are arriving at an overall picture of Romare Bearden Revealed as a record that is not interested in the interplay of imaginary viewing and hearing it promises. Instead, the CD ends up making a very different point. It suggests that jazz can only be understood if the listener is literate in the language of jazz.23 The recording resembles a sound museum of jazz history, each piece invoking a different period. And the implications reach further: this language is seen as a structuring force behind all black art. Therefore, this language is also what we need in order to understand Bearden’s works. In other words, Romare Bearden Revealed subscribes to Murray’s dictum that the “blues idiom” informs all black art because the black artist is conditioned by that idiom.24 The problem is, however, that construing the aesthetic linkages between Bearden and jazz in this way becomes an article of faith. Once one accepts the premise of a blues idiom permeating black culture, almost any work of art that is engaged with blackness on whatever level will do as evidence for proving that linkage. The rhetoric of the blues idiom thus exemplifies what Walter Benn Michaels has called the no-drop rule: the surprising recurrence of an essentialist logic in those critical projects that have moved from race to culture, or from blood to idiom.25 What is more, proving the coherence of the blues idiom—itself an article of faith—becomes increasingly tautological.

In fact, attempts to celebrate the language or idiom of black art across different media run the risk of neglecting the close tie between the metaphors of “idiom” and “language,” and actual narrative. Just as Bearden’s black musicians, through their iconographic value, contribute to actualizing cultural discourses of blackness, so the talk of the black idiom in its very tautological quality recalls and reproduces a narrative of blackness—the telling of which is of course highly political—without which the rhetoric of equivalence would be doomed to fail. An analysis in terms of aesthetic experience would not offer a way out of cultural narratives, to be sure; but it would open up a means of registering the specifics of artworks and thus create a space in between the work and the narrative. As I said, aesthetic experience does not take place in a cultural vacuum. By the same token, it cannot be limited to ever-new versions of the changing same. What an analysis of the aesthetic experience might help us do, then, is to find a way out of tautology in explaining the dialogue between Bearden’s paintings and jazz.

To hear “Autumn Lamp” and “B’s Paris Blues” from the Branford Marsalis Quartet’s Romare Bearden Revealed CD, courtesy of Marsalis Music, please go to the Hearing Eye Web site at http://www.oup.com/us/thehearingeye.

1. Robert O’Meally, untitled liner notes to Branford Marsalis Quartet, Romare Bearden Revealed (Marsalis Music/Rounder Records MARCD3306, 2003), n.p.

2. Critics often point out how close Bearden was to jazz—he was acquainted with many musicians and for a while worked as a composer himself—in order to stress that his creative process closely resembled jazz improvisation. However, as Diedra Harris-Kelley, Bearden’s niece and an artist herself, reminds us, the fact that Bearden often listened to jazz while working, or “told stories of growing up surrounded by music,” should not lead us to equate one art form with another. “It seems impossible,” she writes, “to make direct correlations between music and painting without really understanding the different forms and production techniques, even when artists insist on these correlations…. As much as artists might draw on musical ideas and concepts, playing jazz is not painting.” Diedra Harris-Kelley, “Revisiting Romare Bearden’s Art of Improvisation,” in Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies, ed. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 249–55.

3. Quoted in Myron Schwartzman, Romare Bearden: Celebrating the Victory (New York: Franklin Watts, 1999), 92–93.

4. Quoted in ibid., 75.

5. Let me point out that the critique of naïveté that I am implying here does not apply to Robert O’Meally. In the preface to his anthology The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, O’Meally writes, “Given a certain brashness and command of lingo, anyone can shoot the breeze about the deep-set jazz nature of geological formations, Shakespeare’s sonnets, or—why not?—drugstore hair-nets. This crazy, scattershot impulse already appears in undergraduate papers on American literature or art: ‘jazz’ is everywhere and serves, along with other critical clichés that rumble through the academic culture, to explain away almost any unique or complex issue in its path.” Robert G. O’Meally, Preface, The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, ed. Robert G. O’Meally (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), ix. Nevertheless, in his liner notes to Marsalis’s recording he tends to assert the presence of jazz in Bearden’s work less carefully than his above admonition would suggest. No doubt this is due to the fact that O’Meally is addressing a general audience, which would have little use for the fine-grained distinctions of academic reasoning.

6. Quoted in Ruth Fine, ed., The Art of Romare Bearden, exhibition catalogue (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2003), 209.

7. Schwartzman, Romare Bearden, 16.

8. Cf. Winfried Fluck, “The Search for Distance: Negation and Negativity in Wolfgang Iser’s Literary Theory,” New Literary History 31.1 (Winter 2000): 196.

9. See Wolfgang Kemp, ed., Der Betrachter ist im Bild (Cologne: DuMont, 1985).

10. Romare Bearden, “Rectangular Structure in My Montage Paintings,” Leonardo 2 (January 1969): 14.

11. Ibid., 12.

12. Quoted in Romare Bearden in Black and White: Photomontage Projections 1964, ed. Gail Gelburd, exhibition catalogue (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997), 29.

13. Quoted in Sarah Kennel, “Bearden’s Musée Imaginaire,” in Fine, The Art of Romare Bearden, exhibition catalogue, 141.

14. Albert Murray, The Blue Devils of Nada: A Contemporary American Approach to Aesthetic Statement (New York: Pantheon Books, 1996), 117.

15. Ibid., 118, emphasis in original.

16. Cf. Fine, Art of Romare Bearden, 107.

17. Bearden, “Rectangular Structure,” 14.

18. The Blues and the Abstract Truth is, of course, the title that Oliver Nelson gave to his famous recording for the Impulse! label in 1961. While Bearden, in my reading, was concerned with the interplay of the representational/narrative and the abstract elements to guide the beholder in providing connectivities, Nelson explores a similar dynamic of interplay. The two elements that Nelson negotiates on the record are the standard forms of songs (either the twelve-bar blues or the thirty-two-bar “I’ve Got Rhythm”) and the alterations of these forms through the influence of thematic material. Thus, Nelson explains in the liner notes, “one device which has always been successful … is to let the musical ideas determine the form and shape of a musical composition” (p. 2). Tying this back to the record’s title, one begins to wonder whether Nelson is not punning. In one moment, the blues stands for the musical form—an abstract, rationalized pattern, which lays the ground for the individual melodies and solos. In the next moment, “the blues,” understood as a mood and mode, becomes the idea that determines the form. Thus, Nelson’s record focuses on the interaction of abstract form and narrative or idea. He divides the mutually constituting forces of both poles into alternating compositional strategies, singling out the trajectories from form-to-idea/narrative, and from idea/narrative-to-form, one at a time. In this sense, Nelson’s Blues and the Abstract Truth is directly related to Bearden’s career-long experiment of how to engage with music through painting, insofar as Bearden’s engagement, too, gains momentum by shifting accents from abstraction to form to narrative and back again. See Oliver Nelson, untitled liner notes, The Blues and the Abstract Truth (1961; reissue, Impulse!/MCA IMP11542, 1995), 2–10.

19. Bearden employed the visual pun of spotlight/sun, sometimes paired with a moon, rather frequently in his paintings that feature musical performances. Of The Blues: At the Savoy (1974) is an interesting example: in the picture’s center, above the bandstand, Bearden places a column of four yellow circles. Their vertical alignment makes them readable as stage lights. In addition, he places a larger yellow circle in the upper right corner, which repeats the shape of the stage lights, yet is separated from them by size and site. Bearden explicitly linked both sun and moon to the spiritual traditions of Africa and the African diaspora, and his Caribbean watercolors, in particular, explore the significance of the sun (see, for example, his comments in Fine, Art of Romare Bearden, 123).

20. For a critique of Lisa Kennedy’s concept of the “black familiar,” see Greg Tate’s article “Dark Matter: In Praise of Shadow Boxers,” Souls 5.1 (Spring 2003): 128–36. Tate associates Kennedy’s concept with the widely held idea of “the Black Culture of the Black collective,” which he sees as a counterpart to the equally well-established notion of “the cult of the Black individual” (128). Attempting to displace this dichotomy, Tate argues for a “Black modernity,” which “has always worked the place of the space between the collective and the individual—critically, poetically, and animistically” (ibid.). As successful exemplars in the art world Tate lists, among others, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

21. Romare Bearden, “To Hear Another Language: A Conversation with Alvin Ailey, James Baldwin, Romare Bearden, and Albert Murray,” Callaloo 12.3 (Summer 1989): 433.

22. Mississippi Fred McDowell, Good Morning Little School Girl (Arhoolie 424, 1994).

23. This metaphor of jazz being a language is of course an old one, having been used by a long list of musicians ranging from Louis Armstrong to Wynton Marsalis. Armstrong, for instance, wrote, “Some people don’t understand that the basis of jazz is a kind of language.” Louis Armstrong, “Jazz Is a Language” (1961), in Jazz—A Century of Change: Readings and New Essays, ed. Lewis Porter (London: Schirmer Books, 1997), 186. Marsalis echoes him, saying, “Improvisation itself is a misunderstood language.” Quoted in Howard Mandel, Future Jazz (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 107. But while the metaphor has shifted back and forth between designating the soloist’s individual style (in the sense of “my own language”) and the indebtedness to a shared tradition (in the sense of a “common language”), it is this latter meaning that is clearly privileged here.

24. Murray writes about Bearden: “his basic orientation to aesthetic statement had been conditioned by the blues idiom in general and jazz musicianship in particular all along” (Murray, Blue Devils of Nada, 120).

25. Walter Benn Michaels, “The No-Drop Rule,” Critical Inquiry 20.4 (Summer 1994): 758–69.

Fine, Ruth, ed. The Art of Romare Bearden. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2003.

Gelburd, Gail, ed. Romare Bearden in Black and White: Photomontage Projections 1964. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1997.

Branford Marsalis Quartet. Romare Bearden Revealed. Marsalis Music/Rounder Records MARCD3306, 2003.

McDowell, Mississippi Fred. Good Morning Little School Girl. Arhoolie 424, 1994.

Nelson, Oliver. The Blues and the Abstract Truth. 1961. Reissue, Impulse!/MCA IMP11542, 1995.

Armstrong, Louis. “Jazz Is a Language.” 1961. In Jazz—A Century of Change: Readings and New Essays. Ed. Lewis Porter. London: Schirmer Books, 1997. 185–87.

Bearden, Romare. “Rectangular Structure in My Montage Paintings.” Leonardo 2 (January 1969): 11–19.

———. “To Hear Another Language: A Conversation with Alvin Ailey, James Baldwin, Romare Bearden, and Albert Murray.” Callaloo 12.3 (Summer 1989): 431–52.

Fluck, Winfried. “The Search for Distance: Negation and Negativity in Wolfgang Iser’s Literary Theory.” New Literary History 31.1 (Winter 2000): 175–210.

Harris-Kelley, Diedra. “Revisiting Romare Bearden’s Art of Improvisation.” In Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies. Ed. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004. 249–55.

Kemp, Wolfgang, ed. Der Betrachter ist im Bild. Cologne: DuMont, 1985.

Kennel, Sarah. “Bearden’s Musée Imaginaire.” In Fine, The Art of Romare Bearden Exhibition catalogue. 138–55.

Mandel, Howard. Future Jazz. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Michaels, Walter Benn. “The No-Drop Rule.” Critical Inquiry 20.4 (Summer 1994): 758–69.

Murray, Albert. The Blue Devils of Nada: A Contemporary American Approach to Aesthetic Statement. New York: Pantheon Books, 1996.

Nelson, Oliver. Untitled liner notes. Oliver Nelson, The Blues and the Abstract Truth. Recording. 2–10.

O’Meally, Robert G. Preface. The Jazz Cadence of American Culture. Ed. Robert G. O’Meally. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. ix–xvi.

———. Untitled liner notes. Branford Marsalis, Romare Bearden Revealed. Recording. N.p.

Schwartzman, Myron. Romare Bearden: Celebrating the Victory. New York: Franklin Watts, 1999.

Tate, Greg. “Dark Matter: In Praise of Shadow Boxers.” Souls 5.1 (Spring 2003): 128–36.