Music is my still life, my landscape, my nude.” Ellen Banks is unique among the painters in this book in taking music as the sole subject of her art. Her approach is highly unusual too: her canvases are based not on the sound or performance of music but on musical scores (mostly piano music by everyone from Bach to Cole Porter to Mary Lou Williams), measures from which she translates into colors and geometric shapes using a personal system of correspondences that she devised in the early 1980s. Although at one time she envisioned the music on a large scale—“Bach toccatas about three feet tall and nine feet long, and fugues approximately six feet square”1—in recent years she has focused more on small canvases and encaustics.

Born in Boston in 1941,2 Banks studied both painting and music as a child (she is a classically trained pianist) until—inspired by Mondrian—she elected to concentrate on art. She studied at the Massachusetts College of Art, later worked with César Domela in Paris and Hans Jaffe at Harvard, and was a Bunting Fellow at Radcliffe in 1983–84. She has exhibited widely in Europe but remains less well known in the United States. For many years she taught at Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Art before retiring in 1996. She now lives in Brooklyn, New York, in a house stacked with the canvases to which she devotes all of her time. I talked with her there in November 2003.

GL: You were interested in painting from an early age?

EB: Oh, always. My whole life. Believe it or not, I’m very shy. [Laughs.] As a kid I was incredibly shy, skinny and shy. I thought, if I’m a painter, people will love my paintings and I don’t have to be involved with them. Which hasn’t happened—it doesn’t work like that! No, I always wanted to be an artist. Because I could do it by myself; I wouldn’t have to compromise. In life you have to compromise so much. And who knows what people will want to be? Nobody in my family was an artist.

GL: Did you not want to be a musician at one time?

EB: I wanted to be a dancer. My cousins were dancers but they were men. My mother said, oh no, it’s not a good life for a woman. It wasn’t then: this was many years ago. But I wanted to be a dancer, oh, for years! Now I’m learning the tango. Those childhood desires die very hard. Don’t laugh—I’m very good at the tango!

GL: I thought you’d considered becoming a concert pianist when you were younger.

EB: I was offered a scholarship many years ago by one of the conservatories in Boston. I realized I was not going to be creative as a pianist; I might become a good performer but that’s not creative, that’s interpreting. That’s why I wanted to be a painter; I wanted to see if I could discover some strange relationship, something that no one else was doing—and I am! Even if they’re working with music, they’re not working with it in the same way I do.

GL: I know you wanted to find a way of translating music into painting. Can you talk a little about your experiments with that?

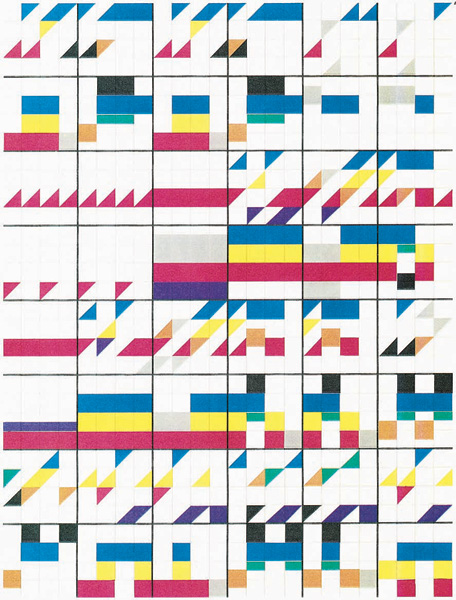

EB: I certainly can. The Scott Joplin piece I showed you earlier, Maple Leaf Rag,3 that was very simplistic, a literal translation (Figure 12.1).

GL: At that time you were assigning each note in the score a particular color?

EB: Right. A is red, B is orange, C is yellow; it’s just prismatic.4 It took me a while to come up with a color for G because there are six prismatic colors and I didn’t know what to do with the seventh note. So I made it neutral and that worked.

GL: And for sharps and flats you use black and gray?

EB: I don’t do sharps and flats anymore. It’s too confining. I just want the structure of the music. I advanced from this kind of form [points to Maple Leaf Rag], which is linear, just like the music, into much more personal structural statements.

Figure 12.1 Ellen Banks, Maple Leaf Rag [page 1]. 1988. Silkscreen, 18 in. × 12½ in. Courtesy of the artist.

GL: Maple Leaf Rag is a silkscreen from 1988, right? But you’d started to do paintings of music before this?

EB: The first piece I did with music was Thanksgiving of 1981: Bartók, Mikro- kosmos. I was in my studio and my husband called: we were supposed to be going to dinner with some people. I said, “Okay, okay,” but I had to finish it. So we got there a little late! [Laughs.] I started with the Mikrokosmos because they’re very simple melodies, really simple. I love that because I’m just looking for musical relationships; I’m not interested in what it sounds like. But it was a successful image; the first time I could get the elements to work together.

GL: What hadn’t been working previously? I know you’d already decided to use only the treble clef.

EB: I still couldn’t get it all into one clef. I was dealing with too many musical items. Above the clef, below the clef. I realized that was unimportant for me, that I just wanted a basic structure to work from. So I stopped dealing with above the clef and below the clef. If there was an A above, I put it in the A space within the clef, because I was looking for patterns, visual things.

GL: Then you translated these within a grid system on the canvas?

EB: Yes. But before I did the music paintings, I’d always worked within the grid as a painter.

GL: Why a grid?

EB: I love it! I don’t know why … Well, okay, I’ll tell you one of the reasons. I’ve never been interested in … I was going to say people, but that’s not true—when I was studying sculpture, all I did was the human figure. But when I’m working two-dimensionally, I’m not the least interested in the figure. I find that … I’m trying to think how to say this without sounding too crazy … I think that what we see is rather unimportant, there is so much in life that is unseen. I love mathematics. I was playing with mathematics and, of course, I ended up with the golden section, which Dorothea Rockburne has done incredible things with, as did the Greeks. I didn’t know how far I wanted to go in mathematics and I had all the music—from studying the piano—so I said I’m going to find geometric relationships in music.

Earlier, I’d seen a painting of Mondrian’s—I guess I was twelve or fourteen— and I thought, well, he’s an artist, so I know I can find what I want to do as a painter. I loved Kandinsky, of course, but he was a little romantic for me. And I love the work of Agnes Martin: I saw her work when I was in Amsterdam. It just blew me away. Anyway, I started working on the grid, doing abstractions, geometric abstractions, based on the dimensions of the canvas: if it was, say, fifty-four by sixty-six inches, I’d divide each side by six, set up a grid, and find patterns in it. Then it became too introspective, too self-indulgent; I wanted something bigger than I, so that’s when I started thinking about music and the geometry within music and working that into a grid.

GL: Tell me more about Mondrian. I know you studied with César Domela and Hans Jaffe; do you see yourself as being in a line from Mondrian?5

EB: Well, I was on a panel once and they said, “How can a black woman relate to a Dutch man?” I said, look, he was a Calvinist, I was a Baptist; from early childhood we were brought up in a grid, in an emotional grid pattern. I mean, I don’t think of the grid so much as restrictive but that’s the kind of thinking we were brought up with, rules and inter-rules! Mondrian was brought up in that too, and so we have that bond. Because I always feel that the arts transcend. The arts don’t belong to any one people. They’re a language that really goes from one to another; it’s just human talk. Like, I find my images come from black women composers and from Bach and Scarlatti: how can I restrict myself to one way of thinking? I can’t do it.

I feel there are certain relationships, emotional relationships, that just transcend race, sex, nationality; certain things are pleasing to everyone. I mean, Europeans love jazz, and that has a black history; I love Bach, who comes from a Germanic background. These restrictions, which were put up out of fear, they’re really not there.

GL: The panel you were on—is this the one you mentioned when we spoke yesterday, from the early 1970s, when some Black Arts people denounced you for liking Bach and Mondrian?

EB: Yes, that’s when I was called an Oreo. I told them, I’m not going to restrict myself! My family was part of civil rights before anyone else. We lived in Boston and my father would take us on cold March days to honor Crispus Attucks, who was one of the first men to fall in the Revolution: he was black. We used to stand out there in the cold; everyone thought we were crazy. My father would talk about Crispus Attucks and a few people would stop and listen. You know, we were there to honor him.

GL: You were explaining how you evolved your method of translating music into painting. How did you come to match colors with notes? Why link red with A?

EB: A is the first letter of the alphabet, so A is red because red is the first color in the prismatic scale. That’s it. Someone asked me, was I getting the colors from the Kabbalah? I don’t even know what that is! It’s just very simplistic. The magic doesn’t happen until I have the patterns and the materials I’m going to work with. So A is red, B is orange, and so on; I just get that out of the way so I’m free to work. There’s no meaning behind it.

GL: Have you ever felt that the colors you end up with don’t seem to fit the piece of music?

EB: That’s not important. I’m not interpreting music: I’m using the structure of the music, not the music itself. I work from the written score; I don’t listen to the pieces I’m working on.

GL: Oh, you don’t even listen to the music? I hadn’t realized.

EB: No, no, no! I don’t want somebody else’s interpretation. If I hear someone play a piece I’m working on, forget it! Because then I’m caught up in their interpretation. I take the score and I want to make a completely different art form out of it.

GL: Do you listen to music at all?

EB: Sometimes. I love music but I’m not a person who can listen to music while I’m doing anything else. Music is all-consuming to me. If I hear music, I have to stop and listen to it. I wish it weren’t like that.

GL: Is there a correlation between the music you like to listen to and the music you like to paint?

EB: Yes. Because I have basically piano music. That’s what I played, so I have all the scores. There are some composers I love and I’m sure I paint them; but I could never play some of the things I paint. There are other composers I like to listen to; but if it’s not piano music I’ve never even tried to paint it. I want to do one thing. Really investigate all the ramifications.

GL: Can you say a little about which composers you like?

EB: Oh yes! Bach, of course, I love. My favorite music is spirituals and Bach. His Well-Tempered Clavier. When I hear someone play that, you can almost taste it! The texture, the wonderful strong texture. That’s one of my favorite pieces. I like Chopin, Mozart—I’m not crazy about his piano music but I love his orchestrations. The big sound! I like Beethoven, Beethoven’s piano music: when he hits that bass, when he gets that bass to move, it doesn’t even sound like a piano, it’s a fantastic noise! You know what I mean? Oh, you’re basically into jazz?

GL: Jazz and the eighteenth century. I’m a big fan of Bach, Handel, Haydn. There’s so much great music out there, I’m still finding things …

EB: This is it … I mean, how much time do you have in life? I don’t have time to do all the things I want to do. Sometimes I become so exhausted, I just stretch out on the couch and go to sleep. I’m sure you do too, no?

GL: Hmmm … I’m not sure I’m that driven.

EB: Oh. [Laughs.] I don’t think of myself as driven, but maybe you’re right. My brother said to me one day, you have such strange energy. Still, look, Paul Klee left, what, 15,000 pieces …

GL: You still have a way to go? I mean, there are a lot of paintings in this room, but even so …

EB: You should see the rest of the house! [Laughs.]

But, yes, there is a correlation between the composers I like and the canvases I paint, because I feel I’m paying respect to them. I have the music here and these are people I’ve known my whole life. I’ll tell you why I learned German: one of the reasons, because there were others. All my adult life I’d wanted to learn German and it was because of the composers I’ve worked with: Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn—they’re all German. I realized the first sounds they heard, that they related to, were the human voice and the German language. They got it from their parents; it was all around them. I guess this was just a romantic kind of thing, but I wanted to go back even further than the music and hear their language. The structure of German is so pronounced that I know some of it has gone into the structure of their music, the way they think about their music. This is the romantic reason why I wanted to learn German. There were practical reasons too; I’ve had several shows in Germany.

GL: When you first began to make paintings from scores, did you start from the beginning of the score?

EB: Yes, but not any more. I used to start by drawing up a whole score, to see what measures worked: now I can look at a measure and see if it has the elements I’m looking for. I need a certain balance in a piece and sometimes if, say, there’s no D or E, I can’t use that measure because it will cluster down into a certain area and make for a terribly unbalanced canvas.

GL: You’re not talking about colors?

EB: I’m talking in terms of pattern, before I put in the color. But as I’m talking, I’m rethinking this because I’ve introduced other elements, like circles and negative spaces.

GL: I wanted to ask about this. Initially you worked with straight lines, horizontal and vertical, then suddenly there were circles. Why?

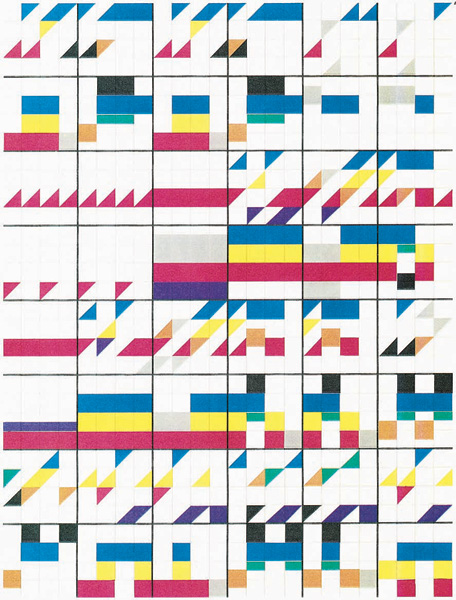

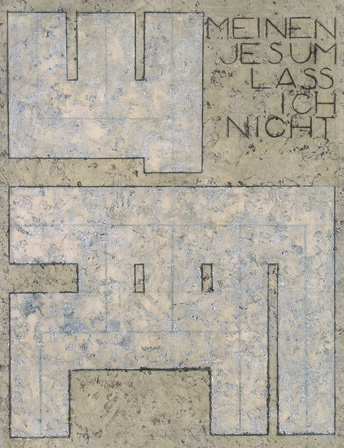

EB: I just wanted to break the interior space, to get something else happening there. So now I’m into circles. And I like text in work. I used the German text in my Bach cantatas, the Oracle series: because this is Bach, it’s coming from an oracle (Figure 12.2). Those cantatas are great: because I’m black I don’t have to deny myself those experiences—first of all I’m a human being. I used the text in the spirituals too; I called that series Supplications (Figure 12.3). Did you see the definitions I gave with supplication?6 I love when it related back to the Romans: another person, another culture, but they’re doing the same bloody thing. We don’t change.

Figure 12.2 Ellen Banks, Oracle #244. 1998. Encaustic, 24 in. × 18 in. [Based on a Bach cantata.] Courtesy of the artist.

GL: Okay, you’ve introduced the circle now, but do you use curved lines at all? Or diagonals?

EB: Curved lines, no, I haven’t gone there yet. I have used diagonals, kind of, for drawing within the form.

GL: Oh, like the little triangles in the Joplin.

EB: Yes. It’ll take me a couple of years to draw a real diagonal. [Laughs.]

Figure 12.3 Ellen Banks, Supplication #2. 2001. Encaustic, 20 in. × 16 in. [Based on the spiritual “Go Down Moses.”] Courtesy of the artist.

GL: Do you not find this a constraint? Not using curves or diagonals?

EB: No, no, I’m very much into what I’m doing. Look at Mondrian, he spent his whole life doing just that. I don’t want to hop around and do a lot of things; I think the more disciplined, the more creative. The less you have to work with, the more you have to manipulate what you have. Maybe when I come back in my next life, I’ll just do circles. [Laughs.]

Figure 12.4 Ellen Banks, Scarlatti Sonata, Allegro in A. 1986. Acrylic on canvas, 48 in. × 48 in. Courtesy of the artist.

GL: I’ve noticed in the works you’ve shown me—the Joplin, the Chopin études, your first Scarlatti sonatas—though they’re all from the mid-1980s, they’re already quite minimalist.

EB: Oh yes, I was a minimal painter. All my work was minimal. You can see how the Chopin relates to the Joplin: the grid is still very pronounced; I’m still using a lot of colors; it’s obvious that this is a clef.7

GL: The Scarlatti, in particular, seems like a distillation. There’s a less literal relationship to the score? (Figure 12.4)

EB: Yes, a stripping away. Stripping away completely to get to the nucleus of the form. Because I want to use the music but I don’t want to be imprisoned by it. I want to take the geometry somewhere else.

GL: Have you worked at all with very contemporary scores?

EB: No, because those scores are beautiful already. I mean, the old scores are beautiful too but they’re written in a very direct language. I don’t understand some of the notations in contemporary scores. A musician friend of mine, a woman I met, gave me one of her scores; it was so beautifully written and had so many notations that I don’t have the imagery for. The imagery was right there in the score. Some contemporary scores … they just have lines or marks, there are no clefs. I don’t know how to handle that yet. I don’t know if I’ll live long enough.

GL: I saw some paintings of yours that were titled Improvisations. Were you still working from a written score?

EB: I always work directly from a written score. But I carry it away from the score. I take the score and I play with it. I say I improvise on it. I don’t know how to put it into words. I take the score into my own field and use it.

GL: I also saw a quote of yours where you say that once you get the structure down, then anything goes.8 What did you mean by that?

EB: Anything goes? What I mean is … basically, I’ll start with the key color— the form is in the color of the key—but if it changes, that’s okay too.

GL: Why would it change?

EB: Because, as you paint, sometimes one color demands another color. Or else, sometimes I don’t put it on right or sometimes I forget and put down the wrong color. When I say anything goes, I mean I’m open to what happens on the canvas.

GL: But the structure is fixed? It stays the same?

EB: It stays the same. Sometimes, if it’s too confining, if it feels confined, I’ll leave pieces off: but the basic form is still there.

GL: How does this differ from the pieces you call Improvisations?

EB: There’s no difference. It’s just a name. Some I call Untitled, some I call Motif; the long thin ones I call Totem, some I call Improvisation. It’s because people like a title to hang onto it. Now I put on the back what work it comes from and what measure it is.

GL: So whether it’s called, say, Chopin or Improvisation, the process is the same?

EB: It’s the same. This is why I was always into integration; this is why … how can I put this? Black music deals with a certain thinking but it’s still a part of music. I don’t have these little separations for race; I never have. I don’t use one method for black music, for spirituals or gospel, and another method for Bach. I use the same method. Sometimes I go to different composers to find different patterns, different ways of thinking. I have found that … because with the spirituals the music came after the words—people had the words and they would use whatever kind of music they could make, so the written scores came afterward—because of that I cannot find some of the intricate, challenging patterns in the spirituals that I can find in other music that is just about music.

I tried to do some spirituals in 1985 and I couldn’t do them; they were too close to my family and my childhood. I would end up just sitting in my studio crying. I could not deal with them. Isn’t that strange? Emotionally, I was too raw. I was trying to think of them as just patterns but I would read the texts and it would bring up all of the stuff from childhood and the prejudice, the sadness, and I just couldn’t do them. But in the past few years, I’ve been able to do them; in the late ’80s, early ’90s I did them on paper.

GL: Oh, I saw those at the Schomburg. How did you get all those wonderful textural effects on the paper? (Figure 12.5)

EB: Complete and utter chance. The paper just happens. I make my own hand-made paper and I don’t make it right. [Laughs.] If you make the paper correctly, it comes out smooth. I learned how to make it but somehow I didn’t make it correctly, so that’s why it has all the crinkly edges and holes in it. I love it! I thought, forget it, I’m not going to take another class to learn how to make it correctly.

GL: I think it works really well for the spirituals. They look and feel like ancient sacred parchments. The colors seem different too, more intense.

Figure 12.5 Ellen Banks, Song Book of Negro Spirituals, Measures 15 and 16. Early 1990s. Mixed media on paper, 6 in. × 8¾ in. Courtesy of the Art and Artifacts Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

EB: They’re smaller so I could paint those more intense colors. When I got to larger paintings, something happened … When I used the intense colors in the larger paintings, they were kind of off-putting because it was too large. In the smaller paintings, they’re fine; I used them in the Bach too, those colors. But in the larger paintings I had to give you more space to relate to the forms, so I couldn’t use those colors. You know, I want my paintings to be human, I want them to go into human places. I think the time of those huge paintings is gone. I do encaustics now and I cannot paint them large. I think it makes them much more human because encaustics you can dust; you can take a soft cloth and go over them and you get a sheen—the wax comes alive. (Figures 12.2 and 12.3 are encaustics.)

GL: How does the encaustic process work?

EB: You melt the wax and then you apply it with spatulas, with brushes, whatever works for you. And you can go back into it with an iron or a heat lamp and melt it and manipulate it. That’s what encaustic is about.9

GL: Then you paint on top of the wax?

EB: Sometimes, yes. I do, quite often. You can also color the wax, which I’ve done. I make my own media, so I make my own wax. I have a formula for it: I just put the pigment into the melting wax and see what happens. [Laughs.]

GL: I saw some slides of your Villa-Lobos pieces at the Schomburg. They seemed to be on a different kind of material again.

EB: I was doing those on burlap. I used to be far more involved with the composer and I thought—burlap for Villa-Lobos! You know, that lusty, warm feel. I don’t do that anymore. I’m much more into how I want to use paint … It’s stripping away more and more.

GL: Even so, you’ve done series on the spirituals, on black women composers, Bach cantatas, Scarlatti sonatas; you’ve done Beethoven’s rondos—on circular canvases!—and his Diabelli Variations, thirty-three paintings on paper, one for each variation! It seems you prefer to work in long series.

EB: I think it’s the only way to get to know the subject. When I was studying piano, I wanted to study only Bach for a year: I thought that would be very exciting. My piano teacher said, no, no, that would be awfully boring, and he wouldn’t do it with me. So yes, I always like to study, to work in series.

GL: Talking of study, you taught at the Boston School of the Museum of Fine Arts for many years?

EB: Right. From 1974 to 1996, twenty-two years. Of course, I took years off. I lived in Paris for a year and I worked at Radcliffe—that was the year I had my solo show at the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover. Since I stopped teaching, I’ve just been painting. I was with a gallery in Paris … because of the nature of my work … Galleries here, quite often, if they’re carrying a black artist, they want it to be obvious that it’s a black artist. Like, kudos for us! [Laughs.]

So I’ve had problems. I had one dealer say to me, “I think your work is beautiful and incredible but I can’t put your work with you.” It isn’t that I’m not beautiful and incredible [laughs]—but I knew what she meant. I said, Oh! Because my work, as you can see from looking around, is definitely a part of me. When she said that, I was a little taken aback. Others have implied it, but she was the first one who came up and said it to me. So I do run into that. That’s why I showed in Paris—they don’t have this stereotypical idea about a black woman—and I’ve exhibited in Amsterdam and in Berlin at the Spandow Gallery.

GL: Did you enjoy teaching?

EB: Oh no, I hated every minute that it kept me from painting. And I’ve lost more years. I lost all the years … when my husband and I were in India, he became very sick and we had to go to the hospital in India, and then we came home and it was all I could do to take care of him and teach. So my painting suffered a great deal. Then, after he died, I was going back and forth to Boston, and then they found I had cancer.

Dear God, through it all I paint! But the production’s cut down a little. So that slowed me down. Now I’m fine, as far as I know. But it kind of slows you down. That, along with age. That’s why I’ve decided to get a cleaning woman. As you can see, I don’t clean. [Laughs.] I just can’t do it. All I do is paint. For pleasure I read German and work in the garden and walk the dog. But I don’t clean. I love my music and my painting, and I’m not hurting anyone; so I’m going to do what I want to do.

To see more paintings by Ellen Banks, including other works inspired by the spirituals and by Bach, as well as two based on compositions by Mary Lou Williams, please go to the Hearing Eye Web site at www.oup.com/us/thehearingeye.

1. Quoted in Alicia Faxon, “Ellen Banks,” in Gumbo Ya Ya: Anthology of Con-temporary African-American Women Artists, ed. Lesley King-Hammond (New York: Midmarch Press, 1995), 7.

2. Faxon gives her year of birth as 1938 but other sources have 1941; Banks has confirmed in personal correspondence that 1941 is correct.

3. Banks created Maple Leaf Rag as a series of silk screens that was printed by Nexus Press in Atlanta and published in 1988 as an “accordion book,” a phrase Banks says she took from Rudi Blesh’s introduction to Joplin’s collected piano scores.

4. According to a statement that accompanied the published version of Maple Leaf Rag, Banks

translates Scott Joplin’s written piano score into a visual scaffolding onto which notes and tones are assigned specific colors and densities. Accordingly, grouping of notes and rhythmic silences determine both positive and negative spaces.

The grid is an integral component of the work since it is the equivalent of the treble and bass staffs modified into four spaces and three lines. Their orientation is similar to the written score without the intervening spaces. All notes, whether above or below a given staff, are placed within the appropriate staff. The note, or tonic which designates the key of the work, is red. The colors are used in prismatic sequence; red = A, orange = B, yellow = C, etc. Thus, in the first measure in the treble or upper staff A / red is struck; the next note is E / blue and for the third we return to A / red. These are all half beats, since the triangle fills half the space. In the lower / bass staff, second group of four down, again A / red is struck; however, it is a full beat or square. This is followed by a chord of A, C, and E.

Banks’ intention is not for her viewers to “read” these scores in literal fashion, but rather to focus on the visual play of tumbling notes and color, the negative/positive spaces which are created, and the resulting chromatic harmonies.

Uncredited statement in Ellen Banks, Maple Leaf Rag (Atlanta: Nexus, 1988), n.p. Thanks to Ellen Banks for sending me a copy of this statement. (There are more pages from Maple Leaf Rag on the Hearing Eye Web site.)

5. Hans Jaffe wrote about the de Stijl movement and was Mondrian’s biographer; César Domela was “the last living member of de Stijl and a friend of Mondrian until Domela’s introduction of the circle into his imagery drove an ideological wedge between the two.” Stephen Westfall, untitled note, Ellen Banks: Recent Paintings, exhibition brochure (New York: Andre Zarre Gallery, 2003), n.p.

6. “This series ‘Supplication’ is based on the geometric patterns found in the written scores of Afro-American Spirituals and Gospel music.

“I found it interesting that in Webster’s dictionary there were three entries for supplication.

“1. entreaty

“2. a humble request, prayer

“3. in ancient Rome a religious solemnity observed in times of distress …” From Ellen Banks, The Supplications, undated, unpublished ms. (There are more paintings from the Supplication series on the Hearing Eye Web site.)

7. You can see one of Ellen Banks’s Chopin paintings, Chopin Etude Opus 10 #6, Measure 1, on the Hearing Eye Web site.

8. Quoted in Gerrit Henry, “Ellen Banks: ‘The Rondos,’ ” in Ellen Banks: “The Rondos,” exhibition catalogue (Berlin: Spandow Gallery, 1999), n.p.

9. “The encaustic adds richness and a sensuality and seductiveness that is both an aesthetic and physical pleasure. The malleable wax is stroked by Banks’ touch as she rubs in pigment and paint, gently pushing them into the surface in a gesture of restrained mark making and burning. Tempering the sensuality, however, are the muted range of colors that seem veiled and muffled, more dim glow than brilliant fire.” Lilly Wei, “Encaustic Painting of Ellen Banks,” in Ellen Banks: Encaustic, exhibition catalogue (Berlin: Spandow Gallery, 2000), n.p.

Ellen Banks: Encaustic. Berlin: Spandow Gallery, 2000.

Ellen Banks: “The Rondos.” Berlin: Spandow Gallery, 1999.

Banks, Ellen. “The Supplications.” Undated, unpublished manuscript.

Faxon, Alicia. “Ellen Banks.” In Gumbo Ya Ya: Anthology of Contemporary African-American Women Artists. Ed. Lesley King-Hammond. New York: Midmarch Press, 1995. 7–9.

Henry, Gerrit. “Ellen Banks: ‘The Rondos.’ ” In Ellen Banks: “The Rondos.” Exhibition catalogue. N.p.

Uncredited statement. In Ellen Banks. Maple Leaf Rag. Atlanta: Nexus, 1988. N.p. Wei, Lilly. “Encaustic Painting of Ellen Banks.” In Ellen Banks: Encaustic Exhibition catalogue. N.p.

Westfall, Stephen. Untitled note. Ellen Banks: Recent Paintings. Exhibition brochure. New York: Andre Zarre Gallery, 2003. N.p.