ARCHAEOLOGY AND LAND-FORMS OF WOODLAND AND WOOD-PASTURE

One of the features of an ancient forested soil surface, one that had or has been continued thru several generations of trees, is the presence of mounds and depressions (‘pillows and cradles’) resulting from blown-over and uprooted trees. This pillow-and-cradle topography – widespread in northeastern [United States] never-ploughed lands, and elsewhere in the world – is destroyed in the process of ploughing, a land-use which leaves a smooth surface and clean-cut plough-line in the soil horizons … These ploughland features will then persist even for two hundred years after abandonment, or until new pillows and cradles start forming when trees are again wind-blown.

F.E. EGLER & W.A. NIERING, 1976 [REFERRING TO CONNECTICUT]1

Archaeologists tend to avoid woods: either because they are assumed to be relicts of wildwood that have never known human activity, or because tree roots are assumed to have destroyed the underground stratigraphy, or because dense vegetation interferes with archaeological survey. In reality, English and Welsh woods contain as much archaeology as anywhere else, if not more. Potsherds rarely lie on the surfaces, but badgers sometimes excavate them, and they should be looked for in the tip-up mounds of uprooted trees.

Some features belong to the functioning of woods themselves; others (e.g. coal mines) may have been in a wood but not related to it; others may survive from something on the site before it became a wood. Woods can contain remains of almost any terrestrial human activity, including some seldom preserved outside woodland. The investigator should not pass over the inexplicable: people often send me drawings and photographs of strange earthworks in woods, which I am seldom able to identify.

Natural features are not always distinguishable in the field from artificial earthworks. Landslip terraces (natural) are easily confused with lynchets (artificial); with ponds it is often impossible to be sure which is which.

This chapter deals with the non-living part of woodland archaeology; but ancient trees, especially coppice stools and pollards, are as much part of the archaeology as barrows and charcoal-hearths. Anyone surveying a wood should record both. Archaeology can manifest itself indirectly in such things as nettle-beds growing on accumulations of phosphate.

Faint earthworks may not be visible all the time. They may be revealed when a wet spring temporarily floods the surface, or enhanced by vegetation sensitive to slight differences of drainage. Faint banks or ridge-and-furrow can appear as lines of dog’s-mercury, bluebell or primrose (p.175ff).

SITES OF WOODS

Woodland often occupies particular positions in the landscape, usually not places that are good for growing trees, but places bad for anything else: steep slopes, rock outcrops, flat ill-drained clayland, or old landslips.

Large areas of sandy or stony terrain tend to be heath or moorland, sometimes with woods round their edges. In England most big heaths date from the Mesolithic to Bronze Ages, but there are later examples of woodland turning into heath: for example most of Thorpe Wood near Norwich turned into Mousehold Heath around the twelfth century AD. The heaths of Wollin on the Polish coast arose out of woodland a little earlier, supposedly as a result of too much harvesting of trees.2

Often a medieval coppice-wood adjoins a common pasture or wood-pasture, with a stout bank between. Cheddar Wood adjoins Linwood Common in the Mendip Hills: Wall Wood and Monk Wood adjoin Woodside Green near Hatfield Forest, Essex. Probably the whole was originally wood-pasture, and the lord and tenants did a deal: the lord got exclusive control of the more wooded part in exchange for relinquishing his rights to the trees on the rest.

Ancient woodland strongly avoids ground liable to flooding: that was the most valuable land as meadow. In other countries, woods occur on the flood-plains of rivers such as the Rhine, Danube and Mississippi. A fragment still remains of the last flood-plain wood in Ireland (the Geeragh in Macroom, County Cork). Only in the twentieth century, as meadow lost its importance, have woods arisen on wetland; for example, the birchwood now covering Holme Fen nature reserve near Peterborough, or most of the alder and sallow carrs of the Norfolk Broads. Rising local relative sea level is bringing the latter within reach of high tides: it is an uncanny experience to stand in Surlingham Wood and watch the spring tide creeping around the tree trunks (Fig. 47).

SHAPES OF WOODS

Shapes of woods can be constrained by the environment, for example a long narrow wood following a steep escarpment, or the ‘gallery’ woods bordering streams that are common in Cornwall and in many other countries. Otherwise, the shape of a wood tells a tale. Does it have the shape of a field that has turned into a wood? Or is it the shape of an ancient wood? Or of a park? Or a common?

Typical shapes of ancient woods (Fig. 187) are sinuous, as in Hayley Wood, or zigzag, as in Kingston Wood nearby. The irregular curves date from a period before people saw any virtue in straight lines; they may represent a boundary that had to find its way between the trees of a wood-pasture. Zigzags may represent successive stages in grubbing out a bigger wood. Woods seldom have roads within them: where a road appears to cross a wood, either the wood or the road is modern, or the road really separates two woods, with a woodbank on either side.

Wood-pasture commons (including wooded Forests), in contrast, have straggling outlines, funnelling out by horns into the verges of the roads that cross the common. The houses of commoners, scattered round the edge, often define the outline. There can be enclaves of private land, including private woodland, within the common. Wooded commons are no different in this respect from unwooded commons. Norfolk and Dorset, before the Age of Reason caught up with them, were permeated by a spider’s-web of ramifying commons, some wooded, some not.

Parks often have a very distinctive shape, a rectangle or pentagon with rounded corners. The special feature of a park was an expensive deer-proof fence or boundary wall, hence the need to shorten the boundary.

EARTHWORKS BELONGING TO WOODS

Woodbanks

In much of England ancient woods are surrounded by banks and ditches, following all the bends and zigzags of their outlines. Normally the bank is on the inside and the ditch on the outside (Fig. 48); exceptions raise the suspicion that the site was once a park (Fig. 49).

The earliest woodbanks that I know are faint ones bordering the holloway of the ‘Roman Road’ – really an Iron Age road – through Chalkney Wood, Essex. Most big woodbanks seem to be of Anglo-Saxon or early medieval date.

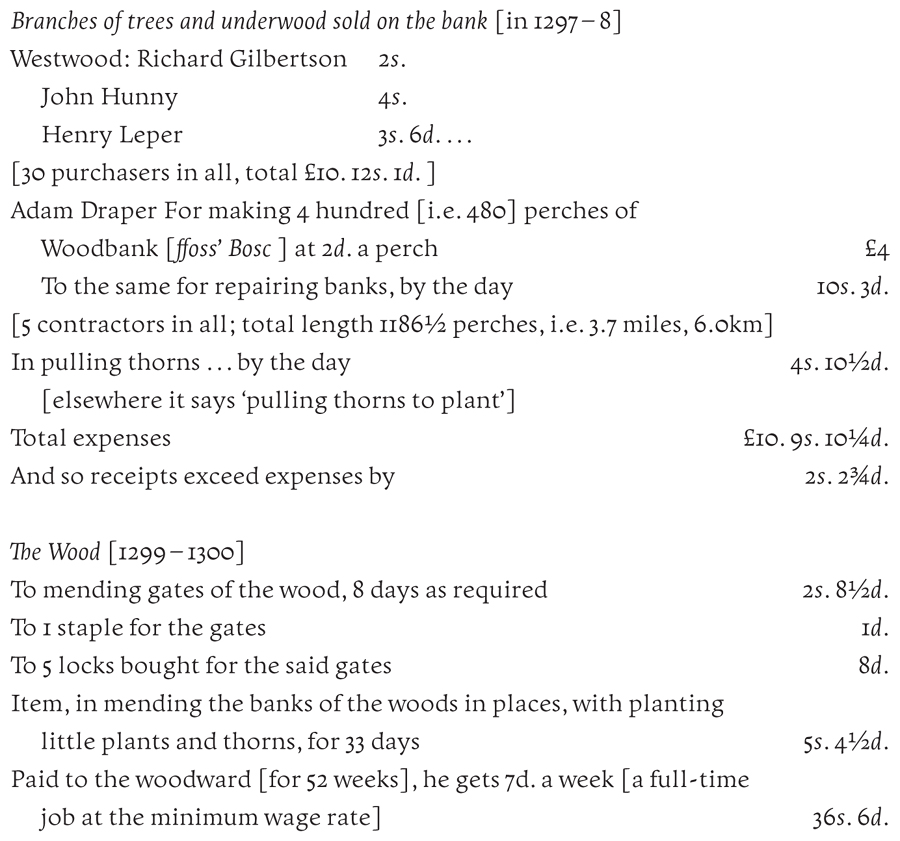

At Hindolveston (Norfolk) the monks of Norwich Cathedral, having converted their two big woods from timber to underwood production, hired contractors to make 3½ miles (5.5 kilometres) of new woodbank round the woods. Their account-rolls record the following:3

They built bridges at the entrances, supplied gates with ‘feterloks’, and planted a hedge, all at a cost of £10. 10s. [roughly £7,000 in the money of 2006]. The date, 1297–8, is rather late for a major woodbank. One of the woods still exists, surrounded by a massive bank and ditch at least 30 feet (9 metres) in total width (Fig. 50). Accounts of woodland in the Blean, east Kent, record the making of what appear to be new woodbanks in the 1230s, 1250s and 1290s.4

Woodbanks were made whenever a new wood-edge was created by subtracting from, or adding to, a wood. By the eighteenth century wood edges were often in straight lines. Banks became steadily less substantial, until in the nineteenth century they were no more than a hedge of the same period, with a feeble bank and a single row of planted hawthorns (Fig. 51). The latest woodbank known to me was constructed through Gravelpit Coppice, Hatfield Forest (Essex), when it was reduced in size in 1857.

Internal woodbanks were made when a wood was subdivided between owners. In Gamlingay, when the biggest manor was divided in the twelfth century, two-thirds and one-third, so was the wood (see Fig. 179). The predecessors of Merton College and of the Avenells insinuated a ditch between the trees; each began at the perimeter bank, keeping the bank on his own side of the ditch, and met in the middle where the bank switches sides. The ditch is still there, 400 years after Merton bought out the Avenells and no longer needed it. In Hockley Woods, south Essex, such a process continued when successive farms were split off the big estates, each taking and embanking an acre or two of wood. Subdivision typically went on until the late Middle Ages, after which the woods were gradually re-amalgamated into one ownership.

Presumably banks originally had a triangular section, which would slowly wear down to a rounded profile; leases of woods often required the lessee to clear out the ditch. Later banks tend to be more triangular and less worn down, though I hesitate to date an earthwork by its state of preservation. Banks are often asymmetrical, steeper on the outside.

Where a wood is on a slope, a lynchet tends to obliterate the ditch. If there is a field below the wood, the soil creeps away down the slope, leaving the woodbank at the top of a little cliff; if a field is above the wood soil creeps down to fill up the ditch and pile against the bank (Fig. 188).

Very big woodbanks were made by ecclesiastical landowners. In Chicksands Wood (Bedfordshire) a huge bank stands on the monks’ side of the ditch that separates their part of the wood from the secular Pedley Wood (Fig. 52). In the woods around Canterbury one can detect the different styles of woodbank profile favoured by the Archbishop, Christchurch Cathedral, St Augustine’s Abbey and other, mostly spiritual, wood owners.

Not every ancient wood was embanked. Richard Gulliver comments on the scarcity of woodbanks in the Vale of York.5 Forest regulations sometimes stipulated that woods shall have a ‘low bank and hedge’ so as not to discommode the deer. This rarely seems to have been observed. The banks of the woods in Hatfield Forest are not much less substantial than those of non-Forest woods. However, the nearby wood called Canfield Hart and some of its neighbours, although unquestionably medieval, are surrounded only by a ditch with no bank: although a bank helps to stabilise a wood’s outline it is not essential. Wychwood Forest (Oxfordshire) was a large wooded Forest compartmentalised into Copses (woodland) and Lights (grassland) (Fig. 189). In what is left of the Forest the Lights follow dry valleys and the Copses occupy the limestone ridges; although they have been stable for centuries the divisions are not marked by any earthwork. (Soils over the limestone are thin, making this an example of the ‘trees on rock, grassland on soil’ principle.)

In stone-wall country, such as west Cornwall, there may be a boundary wall as well as, or instead of, a woodbank. The wall may act as a facing to the outer slope of the bank. On the top boundary of Cheddar Wood, Somerset, dividing the wood from Linwood Common (Fig. 190), the bank evidently came first and was then revetted with a wall, which was left unfinished. Around Sheffield, Melvyn Jones distinguishes three types of woodbank profile and three types of bank-plus-wall, as well as walls only.6

Woodbanks and wood-walls may not coincide with the present edge of a wood. Most of the woods of the Mendips (Somerset) extend beyond their banks: the woods increased in the twentieth century as the adjacent commons fell out of use. At the top of Cheddar Wood a fringe of woodland outside the woodbank was already there on the Ordnance Survey map of 1883; this fringe is of hazel and therefore antedates the coming of the grey squirrel.

The investigator should make a map at a scale of 1:2,500 of all the woodbanks and other earthworks, recording their width, on which side is the bank, any notable features of the profile, and any significant trees.

Trees on woodbanks: On many woodbanks are pollard trees of various species, typically halfway down the outer face of the bank. These are usually the only ancient upstanding trees in an ancient wood.

On slippery clays, woodbanks, even worn down by centuries of rain, are not negligible obstacles to getting into a wood. They were reinforced by a hedge at the level of the pollards. Remains of the hedge may have grown out into mighty and grotesque shapes. An ancient ash stool, its horizontal boughs plashed (‘laid’) in the line of the hedge, is a surreal object, as are the towering gnarled beeches that surround some woods in southeast Wales.

In southeast England, coppice compartments (cants) in woods are defined by low pollards called cant-marks, often not on a bank. These established the boundaries whenever a cant of a wood came up for sale at a coppice auction.

Woodbanks in other countries: Woodbanks were an investment expressing the value of woodland and the importance of woodland conservation, especially round small woods where the bank can, on occasion, take up one-sixth of the entire area of the wood.

In Wales, the bigger and more compact woods are often embanked, but mosaics of woods on rock outcrops and fields on pockets of soil are not demarcated. Many woods do not fill the space inside the wood-wall, as though they have shrunk at their up-slope edges.

In Scotland, the story is more complex. Pinewoods and birchwoods are not confined; indeed the biology of the trees requires that they have room to move around (Chapter 16). Professor Smout demonstrates the ‘dyking’ of woods, especially oakwoods, in the seventeenth century and later.7 Whether this happened in the Middle Ages is uncertain; some Lowland woods, such as Garscadden Wood near Glasgow, have ancient banks around and within them.

In Ireland, some ancient woods were embanked, although with rare exceptions (such as St John’s Wood) so little remains of their perimeters that woodbanks seldom survive. Often, as at interfaces between wood and bog in Killarney or between wood and limestone pavement on the Burren, I can find no boundary feature.

In Belgium, boundary banks, sometimes very thickly set with pollard trees, are a feature of big ancient woods such as the Forêt de Marchiennes. From the early sixteenth century there survive a series of drawings of a massive bank defining a monastic property boundary: it had gates and stiles, and sizeable coppice stools and a plashed hedge grew on it.8

Woodbanks are common in northern France. Around the (part-wooded) Forêt de Fontainebleau, south of Paris, I found a bank and ditch with reverse orientation (ditch on the inside), having sarsen-stone pillars to mark the boundary. A stronger bank, with normal orientation, marks the boundary of the (wooded) Forêt de Chantilly northeast of Paris. In both places the wood now sometimes extends beyond the bank. The monks of the great Abbey of Bec (Le Bec-Hellouin, Normandy) took the boundaries of their local wood seriously. Its perimeter, 5 miles (8 kilometres) long, is surrounded by a massive, sinuous bank with a mortared stone wall on it; lesser banks subdivide the interior (Fig. 53).

In America, woodland was usually too plentiful and labour too scarce for making woodbanks. I have found banks between wood-lots and fields on Cumberland Island off the Georgia coast, but that was a land of slavery where jobs might need to be found to keep slaves busy at slack times of year. In Japan, weak banks, with pollard trees on them, sometimes demarcate lanes between private coppices, or the boundary between the sacred grove of an ancient Shinto shrine and a private pinewood. Where a wood adjoins a rice-field the farmer has the right to maintain a ribbon of grassland to prevent the trees from shading the crop. These buffer zones, imbatsuchi, are old grassland, part of the elaborate interrelation of semi-natural habitats that forms the satoyama landscape of old-fashioned Japan.9

Woodbanks as habitat: Woodbanks create a special environment and add to the diversity of a wood. In wet woods such as Hayley badgers make setts in the bank. Woodbank soils tend to be less acidic, better drained and often more clayey than the rest of the wood, and may have distinct vegetation: in an ashwood with bluebell the bank may be a strip of maple-wood with dog’s-mercury.

Tip-up mounds

Why is the general surface of English woods (away from earthworks and geological features) usually almost smooth? Successive storms ought to have uprooted trees, which – decades later – would have died and rotted away, leaving a pit where the roots were torn up and a mound beside it representing the root-plate.

Tip-up mounds are common in northeastern North America, and indicate which areas are primary forest that has usually been felled but never cultivated, and which are secondary on ex-farmland. In New England historical ecologists, by studying the rate at which mounds degrade and the superposition of successive mounds, have identified traces of hurricanes of 1944, 1938, 1821, 1815, 1635, and c.1450.10 The Alleghany National Forest, Pennsylvania, is full of ‘pillows and cradles’ except in parts that have been cultivated (Fig. 54); these result from tornadoes, and when I was there in 1999 a tornado had just generated a new crop.

Tip-up mounds are rare in Britain. They have been reported by archaeologists from sites now outside woodland: at Sutton Hoo (Suffolk) pits and mounds were found with Neolithic pots carefully deposited in the pits.11 On Rodborough Common near Stroud (Gloucestershire), Dr Michael Martin tells me of pits, now in grassland, but with wood-anemone (an ancient-woodland plant, Chapter 12) growing round them, possibly due to the storms of 1602 or 1703. The blowdown of 2004 in the Tatra Mountains of Slovakia was not a unique event; there are plenty of tip-up mounds from previous storms.

Most ancient woods have had centuries of coppicing, with little opportunity for trees to grow big enough to get uprooted. Even so, there ought to be traces of mounds dating from before coppicing began. They should be visible in woods such as Hayley, on clay soils that preserve earthworks well, and in seasons when waterlogging brings out details only an inch or so high, but I have never found them.

Tip-up mounds are generated now, especially when great beeches uproot; in Hayley Wood the storms of 1987 and 2002 produced some from ashes and maples. In the Middle Ages there were regular arrangements for disposal of cablish, wind-fallen wood, not only after exceptional storms like that of 1362. However, trees often fall or perish without generating mounds. An elm that dies standing and falls to pieces gradually will not leave a hole, nor will a lime that rots and breaks at the base. An oak that dies of Phytophthora or honey-fungus stands until the roots rot, and falls leaving only a small hole.

In overcrowded plantations and neglected woods there are now far more trees of the size and age to uproot than in past centuries. But why are there not faint pits and mounds from prehistory? Did trees then not fall in ways that created them?fn1 Were there not enough big youngish trees to uproot? Or not enough great storms? Or is there some process that effaces mounds?

In the redwood forests of California I can find no trace of ancient pit-and-mound, although today these colossal trees quite often topple over leaving prodigious root holes.

Stumps

Another surprisingly rare feature is oak stumps in the last stages of decay. Many woods are full of stumps of oaks felled during or between the World Wars; these are eroded at the surface and the older ones are detached from the ground, but they are still very recognisable: a dead oak stump evidently takes more than a century to disappear (Fig. 56). (Most other species last less long.) Why are there not very degraded remains of stumps from earlier fellings? Fewer oaks than usual were felled between 1860 and 1914, but some were, and they should have left recognisable stumps. Is this due to a change in the method of felling?

‘Grub-felling’ by cutting through the roots is recorded for certain Norfolk woods in the nineteenth century. It would have the advantage of yielding a foot or two more of the valuable butt end of the tree. It ought, however, to leave a recognisable pit. Documents and place-names from Anglo-Saxon times onwards prove that stumps and stocks of trees were familiar objects. I have often seen medieval timbers with the marks of an axe on the butt end (showing that they were felled in the conventional way), but never with the stumps of roots.

The investigator should get into the habit of noting stumps, whether they are oak, their size, and (with experience) how recent they are.

Charcoal-hearths

Walter [de Fynchyngfelde] had four charcoal hearths in the said cover, to the destruction of the forest and the detriment and escape of the king’s beasts.

HATFIELD FOREST, CLOSE ROLLS, 1336 (EDITOR’S TRANSLATION)

Charcoal is made by setting fire to wood and cutting off the air supply. Once started the process is self-sustaining: the chemistry of the wood is broken down, the volatile constituents evaporating as gases and fumes. What remains is a fraction of the weight of the wood with a larger fraction of its heat of combustion. The structure of the wood is unaffected, and microscopic details can still be identified in charcoal thousands of years old from archaeological sites.

Charcoal is a lightweight fuel, cheaply transported, though fragile and difficult to carry more than 15 miles (25 kilometres) unless by barge. A pound of charcoal produces more heat than a pound of wood, though less than the 2½ pounds or more of dry wood needed to make the pound of charcoal. It was favoured as an urban fuel, where the cost of transport mattered more than the cost of trees. Charcoal can be made to burn at a higher temperature than wood, or any other fuel before the invention of coke (which is coal converted to charcoal). It was used (and still is to a smaller extent) in high-temperature industries like iron working. It was produced in bulk in the Chilterns and other woods that supplied London, or that supplied iron-furnaces as in the Weald, southern Lake District, Forest of Dean, South Wales and Argyll. It was also made wherever there were woods, to supply blacksmiths and other local users: charcoal was a convenient way to use up branchwood and oddments.

Often the species does not greatly matter, though hard charcoals such as oak are more transportable than fragile species such as pine. For gunpowder the charcoal was normally alder, whose structure produces the intimate mixture of carbon and potassium nitrate needed to achieve a predictable explosion. Alder coppices established round the Royal Gunpowder Factory at Waltham Abbey are still there.

The Italians, who took charcoal seriously, worked out the weight of charcoal produced by a given weight of wood: 16 per cent with pine, 18 per cent ash, 19 per cent beech, 20 per cent oak, 24 per cent maple, and 25 per cent larch (apparently based on the fresh weight of wood).12 In practice wastage usually reduces the yield to 12–15 per cent.

Underwood of no more than 12 years’ growth or branchwood was normally preferred. Charcoal was at first made by burning wood in a pit, hence the ‘coalpits’ in medieval documents in places where there was no mineral coal.

The classic method, recorded by Theophrastus in the fourth century BC,13 was to build a stack of logs, cover it with earth and straw, ignite it from within by a secret method, and watch it day and night for a week as it smouldered into charcoal. In the New Forest this method flourished in the nineteenth century, but mysteriously collapsed after 1880, apart from a brief revival to make charcoal for gas masks in World War II.14 Charcoal was later a by-product of pyroligneous acid factories, and is now made in steel kilns.

Details are poorly documented: writers and artists were more interested in the charcoal-burners’ cabins than in what they did. A charcoal-stack requires a circle of level ground 20–40 feet (6–12 metres) across, often misleadingly called a ‘pit’ or ‘pitstead’. On flat ground, as in Hatfield Forest, there is little hope of finding the site, but on a slope it appears as a circular platform scooped into the hillside. Charcoal-hearths were used time and again as the woods were felled and grew up. They are often in groups, served by one track, as men watching a stack burn could use their time building another stack and dismantling a third. Under the leaf-mould there is a layer of charcoal fragments, from which the species and size of wood can be identified.

Charcoal-hearths can be found in most sloping woods of north and west England, and in Wales, Scotland and Ireland. In the Derbyshire Peak six patterns of charcoal-hearth have been distinguished, two of them on level ground. Sometimes there are so many that scraping up earth to cover them would have significantly affected soil and vegetation.15 Around Coniston Water are woods that supplied the ironworking activities of Furness Abbey and its successors from the twelfth to the eighteenth centuries. The woods contain pitsteads at about one per 2 acres (0.8 ha).16 The woods around the Helford River, Cornwall, contain charcoal-hearths that probably served the tin industry, operating in that area in the seventeenth century.

Charcoal-hearths can occur on moorland that used to be woodland. Above the oakwoods north of Abergavenny (Monmouthshire) are brackeny slopes with faint depressions, which turn out to be scooped platforms containing oak charcoal. Charcoal-hearths on moorland, without charred wood, may be for peat charcoal; on the Lizard, Cornwall, these are rectangular.17

Charcoal was a big industry in Italy (which never had a coal age), leaving innumerable hearths in the Apennines.18 I have found charcoal-hearths in surprisingly remote places on Athos, the Holy Mountain of the Ægean: the monks, who made a living from their vast mountain woods, evidently shipped charcoal to urban markets in Thessalonica and Constantinople. There are charcoal-hearths in the gorges of Crete, sometimes where there is no longer woodland.

Whitecoal: This mysterious fuel consisted of wood (of bigger sizes than usual for charcoal) dried in a kiln. It was especially used in lead smelting from about 1550 to after 1750, when a process was invented using coal. Lead smelting used typically one ton of wood (fresh weight) per ton of lead. Whitecoal was added to charcoal to give the right temperature: charcoal alone would burn too hot and volatilise the lead.

For unknown reasons whitecoal was made in the woods, rather than being dried immediately before use. Structures known from their shape as Q-pits occur in woods in lead-working areas, especially north Derbyshire. They are circular, with an entrance gap (‘mouth’) and a trench (‘tongue’) extending downslope from it. How they were used is unclear; some have evidence of a secondary use for charking mineral coal into coke.19

Limekilns

A limekiln was a rough stone tower with an arched entrance, built on a slope. Chalk or limestone and fuel were fed in at the top, and lime extracted through the arch. The heat of combustion decomposed the limestone (calcium carbonate) to quicklime (calcium oxide), used to make mortar or as a fertiliser. The high temperature melts or calcines the inside of the kiln, depending on the kind of stone.

Limekilns were often built near a source of limestone or fuel or both, although even in woodland they might burn coal. Cathedral builders, needing hundreds of tons of lime, often got a friendly king to give them dead trees for a rogus, a kiln attached to the cathedral (where stone-working debris would provide the limestone). In Crete one often finds remains of a limekiln next to an isolated masonry chapel or fort.

WOODLAND PONDS, DELLS AND HOLLOWS

One might expect fewer ponds to the acre in ancient woodland than elsewhere, since most of the activities that create ponds took place outside woodland. This may not be so. The biggest concentrations of ponds in England are in Cheshire, south Lancashire, south Norfolk and north Suffolk; in East Anglia there are even more ponds per square mile in ancient woods than in the rest of the landscape.20 Wolves Wood (Hadleigh, Suffolk) has more than three depressions per acre of woodland. Are these there by chance? Most show no characteristic artificial features nor any plausible explanation for their presence (Fig. 55). Were natural ponds among the obstacles to cultivation that caused a site to be left as woodland?

Ponds, pits and dells (dry depressions) have many different origins. In New England or Ohio innumerable ‘ponds’ represent natural hollows in the landscape as retreating glaciers left it, and this may partly be so in Old England also. They can result from other natural processes and from many kinds of human activity.

Some clusters of ponds are pingos, the melted-out remains of great lenses of ice formed in glacial times where water welled up from under frozen subsoil; they appear as ponds with banks round them, often in recent woodland, but so far not reported from ancient woods.21 Swallow-holes occur where limestone or hard chalk is dissolved by acid waters or reacts with adjacent acid rocks, especially in Hertfordshire and Dorset. They are often conical, with streams mysteriously disappearing into the underworld.

Artificial ponds may or may not be related to happenings in the wood. ‘Hammer Ponds’ in the Weald are dams made to supply water wheels that worked mechanical hammers for processing iron, located in or near woods to be near the fuel supply. The five dams still holding water in Sutton Coldfield Park were made about 1420; they drove, among other industries, fulling mills, a sword mill and a button mill.22

In most coalfields mining goes back to the Middle Ages or before, and has left remains inside and outside woods. Bell-pits are shafts sunk to a shallow coal seam; the miner would undercut the bottom of the shaft as far as he dared and then dig another shaft. They appear as swarms of pits with rings of spoil around them. Drifts or adits are tunnels dug into a seam from its outcrop on a hillside. These too are often in groups, with remains of an access road in front.

Landslips

When a slope is too steep to stand up it gives way. It usually tilts as well as sliding. The breakaway part comes to rest as a terrace, often crescent-shaped and sloping back into the hillside to form a dell. Landslips are commonest where clay underlies other strata and springs lubricate the slip-plane. They occur especially on the coast, where marine erosion takes away the fallen material that would otherwise buttress the slope against further slumps, and in railway and motorway cuttings.

Inland landslips are commoner in woodland than in the rest of the countryside. The trees probably had little influence: tree roots are too shallow to reach the slip planes, although trees could have a minuscule effect by promoting the infiltration of rainwater to activate the slip. Landslips favour the formation or survival of woodland by preventing cultivation.

Good localities for woodland landslips are the Isle of Wight, the Ironbridge Gorge (Shropshire) and west Dorset. In Dorset, with its complex strata of clays, weak sandstones and chalk, they can occur on slopes as little as 5°, making a visit to even the smallest wood an adventure. They appear as steep banks with hollows behind them of bottomless black ooze, sallow-wood full of golden saxifrage, marsh violet, wood horsetail and unusual sedges; they can be lairs of wild sows, liberated in the 1990s. Many landslips are probably of Pleistocene age. More recent ones can be vaguely dated by relation to archaeological features and the growth of trees.

Britain is a stable country where landslips seldom still occur inland; but in the Alps, the Mediterranean and Japan the mountains are still being upheaved and are still shedding loads of sediment. Landslips are a well-known ecological factor in tropical forests, where the exposed rock may only slowly be recolonised.23

WOODS AND ROADS

Now you would never know

There was once a way through the woods.

RUDYARD KIPLING, REWARDS AND FAIRIES, 1910

By far the greater part of modern roads go back at least to the Saxon age, and many thousands of miles of them, the ridgeways, have had a continuous existence going back into times long before history began.

G.B. GRUNDY, 1933

Many parts of England once had a denser network of roads than today, and woodland is a likely place to look for extinct roads.

A difference between woods and wood-pastures is that wood-pastures have roads through them, but woods have roads between them (Figs 187, 208). An example from east Kent is the radfalls, a number of wide, muddy lanes between massive banks that straggle between the Blean Woods. Some of these are through routes, but one seems to be an access lane ending in North Bishopsden Wood, surrounded by woodbanks that suggest it was the last wood in that part of the Blean to remain as common after all the surrounding woods had been embanked.24

Trenches

Commanded … that the highroads from merchant towns to other merchant towns be widened, wherever there are woods or hedges or earthworks, where a man may lurk to do evil near the road, by two hundred feet on one side and by two hundred feet on the other side; but that this statute extend not to oaks nor to great trees, if they be clear underneath. And if by default of the Lord, who may not want to level earthwork, underwood, or bushes as provided above, and robberies be done, the Lord is responsible. And if there be murder, let the Lord be fined at the King’s will. And if the Lord is unable to level the underwood, let the country [folk] help him to do it. And the King wishes that in his demesne lands, and woods within Forests, the roads be widened as is said above. And if by chance a park be near the highroad, it is convenient that the Lord of the park adapt his park so that it have a space of two hundred feet next to the highroad … or he make a wall, earthwork, or hedge such that malefactors may not pass or return to do evil.

STATUTES OF THE REALM 1 97 (1285)

Woods were feared as dangerous places; travellers expected to be mugged when passing them. Two travellers were murdered in the Prior of Barnwell’s wood at Bourn, alongside the road from Huntingdon to Royston, and the Abbey chronicler claimed that the above statute – the earliest legislation concerning woods – was a response. The new woodbanks made on that occasion, by owners of woods in Bourn and across the road in Longstowe, are visible to this day.25

Not all owners of roadside woods hastened to cut trenches, as these clearings were called, because the statute told them to: that is not how medieval legislation worked. Trenches, to give travellers a sense of security against highwaymen, had long been made where roads passed woods, and I know of no new ones after 1285. Whether they did deter highwaymen is unknown: then as now, the sense of security was what mattered.

Some trenches still survive as long narrow fields between woods and roads – sometimes surprisingly minor roads. Others have long since grown over again, but traces can be found as woodbanks set back from the road. A trench, if correctly identified, proves that both the wood and the road existed in the thirteenth century, but its absence does not prove the contrary. Some landowners, such as the De Bohun family in Essex, took their chance of a holdup occurring: their Dunmow High Wood adjoins a Roman road with no trace of a trench.

Watling Street, now the A2, was the great road for pilgrims to Canterbury and travellers to France. The pilgrims in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, having escaped the perils of Shooter’s Hill, Oxleas Wood and Bexley Heath, would have passed through the great ring of woods surrounding Canterbury, in sight of their destination. This large and armed party, telling merry tales, would have given no thought to highwaymen; but others might have been glad of the trench through the woods (Fig. 191). It varies in width from 280 to 420 feet (85 to 130 metres), not the 400-plus feet (120 metres) provided by the statute. It is bounded by sinuous woodbanks, evidently fitted in among the trees. At least four owners were involved; Fishpond Wood, which had a private owner, is less strongly embanked than the others, which were ecclesiastical.

Another trench borders the present A121 road through Epping Forest (see Fig. 183). Being in an uncompartmented Forest, it has no woodbanks; it is now overgrown, but can still be detected as the ancient pollards stop abruptly at a line about 180 feet (55 metres) from the road on either side.

Edward I, when invading Wales, conscripted hundreds of woodcutters to fell trenches along the roads to protect his communications.26 Whether they grew up again as soon as Edward’s back was turned, is not recorded.

In France concerns about highwaymen lasted much longer. The Cassini maps, c.1755, show hundreds of tranchées where main roads traversed woods, and many still survive. Trenches are typically 200–230 metres (about 650 feet) in total width, often used as arable fields (e.g. ‘Les Cinq Tranchées’ in the Forêt de Haye outside Nancy). Some are sinuous and could be medieval, as along the main, supposedly Roman, road through the Forêt de Sommedieue from Verdun to Metz. Others border the straight main roads attributed to Louis XIV.

Roman roads

Disused Roman roads quite often run through woods, appearing as low, flat-topped earthworks, for example in Grovely Forest west of Salisbury. The main Roman road to Dorchester through Cowpound Wood, Athelhampton, has massive earthworks to overcome a steep gradient. Most disused Roman roads lack trenches and woodbanks; they probably fell out of use before these came into general use.

Occasionally an unknown Roman road comes to light in a wood, as with the faintly raised, flat-topped earthwork across the Bradfield Woods, west Suffolk, overlain by the spoil-banks of the later excavation called the Fishpond. Conversely, a search of ancient woods can disprove the existence of a Roman road. At Barking (Suffolk) the known Roman road from Long Melford, if prolonged in a straight line for COMBRETOVIUM (the predecessor of Ipswich), has left no trace in Priestley or Swingens Woods, documented to the thirteenth century (see Fig. 186). It must have turned aside to join a preceding road (still in use) to reach its destination by a less direct route, avoiding a steep descent.

Holloways

Lanes sunk below the land surface are erosional features: centuries of hooves, wheels and feet have ground away the soft surface, and heavy rain has washed away the debris. They are especially common in Monmouthshire, Dorset, west Suffolk and the Weald. They are undatable: many are already cited as holan weg in Anglo-Saxon charters. Holloways tend to turn into linear woods as trees grow on the steep or rocky sides: they may acquire woodland plants such as bluebell, primrose, and even moschatel. Further erosion undermines the trees and leaves their roots dramatically overhanging the road.

Many lanes through, or rather between, woods are holloways (Fig. 57). A narrow lane, which can hardly have taken carts, descends through Merthen Wood, Cornwall, to a quay on the Helford River.

A holloway that enters a wood-pasture common by one of its horns, or by a ford across a stream, may split into several tracks, either to reach different destinations across the common, or because travellers would divert round difficult parts of the track. In disuse these can create puzzling bundles of gullies.

Tracks within woods

The common pattern of straight woodland rides, often with ditches on the uphill side or both sides, is usually of eighteenth-century or later date. However, the rides that divide Norsey Wood, Billericay, into six divisions appear on a map of 1593.27 In French Forests, such as Fontainebleau, grids of straight rides radiating from a point known as a patte d’oie (‘goosefoot’) are said to have enabled eminent hunters to ride around on horseback or in carriages. English examples are in Hatfield Forest (eighteenth century), Savernake Forest, and Oakley and Hailey Woods (Cirencester), all associated with important estates. Rides within woods must not be confused with highways between woods (with a woodbank on either side) or the tongues of plain that sometimes separate woods in a compartmental wood-pasture (see Fig. 184).

Constructed tracks on slopes often lead to mines or clusters of charcoal-hearths. In Cheddar Wood in the Mendips hollow tracks leading straight up the very steep slope are said to have been for sliding down wood or timber.

EARTHWORKS THAT HAPPEN TO BE IN WOODS

Barrows

Barrows – burial mounds ranging from Neolithic to Anglo-Saxon in date – were normally built in grassland or heath, often carefully sited to be visible from a distance. Some, however, are now in ancient woodland. Within Wychwood Forest are several long and round barrows and chamber tombs (see Fig. 189). Wychwood was one of the big wooded areas in medieval England, but much of it was evidently non-woodland from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age.

Field systems

Most ancient woods show no traces of cultivation, but there are many exceptions. Strip lynchets are narrow fields (like terraces but lacking stone walls) that follow the contours on steep slopes, usually on chalk or limestone. Sometimes they extend into ancient woods, as in Westridge Wood, Wotton-under-Edge.

Madingley Wood, Cambridge, is the scene of 350 years of botanical studies. Some of its earthworks relate to the medieval boundary of the wood, some to the grubbing of four small fields from the wood in the seventeenth century and their subsequent re-incorporation into the wood. Underlying all these is a grid of massive banks and ditches, which seem to define a system of small squarish ‘Celtic Fields’ (Fig. 192). This was confirmed when a pipe-trench in 1994 revealed a large Iron Age to Roman settlement just outside the wood. What then was probably a clearing in the boulder-clay woods had, by the Middle Ages, turned into an island of woodland surrounded by fields.28

What may be a planned field system extends under the Blean woods north of Canterbury. Deep ditches define a grid of rectangles, 550 × 210 yards (500 × 190 metres), aligned along the Roman road through Blean village.29

In the last 30 years coaxial field systems, believed to be of various prehistoric dates, have been reported in many different places, including Dartmoor and south Norfolk.30 Parallel but not straight main axes, often roughly north and south, are connected by cross-hedges at irregular intervals.

A test for any such planned field-system is to see what happens when it meets an ancient wood. The clay uplands of west Cambridgeshire, once thought to have changed from wildwood to farmland as late as Anglo-Saxon times, are underlain by about 30 parallel but sinuous north–south axes, visible in the landscape as roads, furlong and parish boundaries. Susan Oosthuizen draws attention to these and shows that they are older than the Roman roads that intersect them.31 Her interpretation is extended and confirmed by including the low bank and ditch that bisect Hayley Wood, which conforms to this system and is extended outside the wood by further parish boundaries (Fig. 193). This in turn is underlain by fainter, apparently older, banks and ditches within the wood, visible as strips of bluebell in an otherwise meadowsweet-dominated area. Even Hayley Wood has not the simple history that we envisaged.

Ridge-and-furrow

This is the physical expression of open-field strip-cultivation, widespread in midland and northern England from late Anglo-Saxon times until the eighteenth or nineteenth century. It consists of ridges, usually curved or with a double ‘reversed-S’ curve, typically around 33 feet (10 metres) in wavelength and one furlong (220 yards, 200 metres) in length. Ridge-and-furrow was also formed in later centuries and outside the ‘classic’ area; late ridges tend to be straight and narrow (Figs 192, 58). Several different profiles have been recognised.32 Anyone interpreting ridge-and-furrow in a wood should remember the need for a headland, a strip of land at the end of the ridges on which to turn the plough.

Many ancient woods in the east Midlands contain areas of ridge-and-furrow, which have therefore not been woodland all the time. Some ridged areas are outside the woodbank and are an enlargement of the original wood. In Buff Wood (East Hatley, Cambridgeshire) four areas of ridge-and-furrow appear to have been added to the wood in the late Middle Ages: they contain ancient coppice stools, and a map of 1750 knows no difference between the additions and the original wood. Out of 18 ancient woods in the west Cambridgeshire group, 11 have expanded over ridge-and-furrow; in five instances these represent medieval, and in six post-medieval, additions to the wood. In two woods (Madingley and the Triangle at Hayley Wood) the ridge-and-furrow itself is of post-medieval date.

Less often, ridge-and-furrow occurs inside the woodbank: sometimes it is faint, and apparently represents an experiment in cultivation that got no further. In Monks’ Wood near Huntingdon about one-sixth of this very large wood is ridged.33 Among ancient wood-pastures, some of the ancient oaks of Moccas Park (Herefordshire) and Dalkeith Park near Edinburgh stand on ridge-and-furrow that must antedate them.

Ridge-and-furrow witnesses to the well-documented increase of woodland in the nineteenth century, but also to an earlier increase in about 1350 to 1500, after the Black Death had reduced the population of England by about one-third. In both periods woodland increased at a time of agricultural depression.fn2

An example – Swithland Wood: The Charnwood area is an outlier of Highland England in the midst of Leicestershire, of hard rock, crags and thin soils, and ancient mixed hedges. In Domesday Book this was the most wooded part of a poorly wooded county.

Swithland Wood has been investigated over many years by Stephen Woodward. At first sight it is an obvious secondary wood, with no distinctive boundary earthworks, and most of it overlying ridge-and-furrow. It has a number of ponds and dells and strong internal banks and ditches. The parts lacking ridge-and-furrow include rocky outcrops containing recent quarries. The name Swithland Wood is anomalous, for the wood is in Newtown Linford parish, not Swithland, which adjoins it to the east.34

The wood has a rich woodland flora including species characteristic of ancient woodland, such as native lime, and a number of great stools of lime, ash and oak.

The ridge-and-furrow forms an irregular pattern around the internal banks, dells and outcrops (Fig. 194). It seems to have been fitted into pre-existing hedged fields. The names of these fields may have been remembered in a record that Mr Woodward found of the wood in 1677, when it was called Great Lynns, Little Lynns and Donham Lynns. This name probably refers to linde or lime-tree; ‘Great Lynds’ was already a wood and was coppiced in 1512.

One expects ancient secondary woodland in Leicestershire. The total woodland area diminished only 20 per cent between 1086 and 1895, so most woodland grubbed out in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries was replaced later. The men of Linford probably hewed some fields out of a wood on the edge of their territory. They left strips of woodland to act as hedges, and groves on thin soils and around dells and other uncultivable patches. Later, imitating their open-field neighbours in east Leicestershire, they created ridge-and-furrow on the new fields. After the Black Death these poor fields were the first to be abandoned and to tumble down to woodland, which they have been for at least 550 years.

The oak coppice, as expected, is on the thin, acid soils of the rocky patches. Big coppice stools, as expected, are near the hedge lines. Most of the lime today is on or near hedge lines and other places where the tree would best have survived. Lime away from these places represents occasional colonisation by seed in favourable years. Another factor favouring lime is that some of the trees on this site are of the variant that has weeping branches that hang down and take root.

Terraces

Terraces are the Mediterranean equivalent of ridge-and-furrow. They run horizontally across slopes like strip-lynchets, but are built with stone walls. They are notoriously difficult to date, but some are datable from ancient trees standing on them.

In the twentieth century woodland increased in most southern European countries. Terraces in woods are familiar to Mediterranean travellers; often they are revealed after a fire.35

Moats

Moats are dry or wet ditches round houses, castles, orchards, churches, windmills or haystacks. House moats, typically of a fraction of an acre in extent, were dug in their thousands round farmsteads between 1150 and 1330, with a revival at a higher social level in Elizabethan times. Moats may have deterred burglars and highwaymen; they served for drainage, sewage disposal and fishing; but they are now thought of mainly as a status symbol – the middle-class symbol of a man whose house is his castle, but who does not run to a park. Moats are commonest in Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Worcestershire and Warwickshire; there are many in Ireland.

Many deserted moats appear as groves among fields. Often they are elmwoods, now full of dead elms and live elm suckers, with ivy, nettle, cow-parsley and other plants of woodland with accumulations of phosphate. They rarely have rich floras, though some have been woodland for centuries.

Moats also occur in bigger woods: sometimes by chance, but also there is a definite association with woodland. The west Cambridgeshire woods have 11 moats in or adjoining them. Kingston Wood and its outliers surround a moat that still contains a medieval house; this remarkable arrangement has changed little since before 1720, though the woodbanks indicate changes before then. East Hatley is a shrunken medieval village with 12 moats – an apparently unique concentration – lining the village street. Two of the moats are now in Buff Wood; one of these overlies earlier ridge-and-furrow; nine elm clones are associated with them. In Overhall Grove a big, apparently unfinished moat, with medieval pottery, forms the core of a wood largely on ridge-and-furrow; it is surrounded by massive multiple banks and ditches that may be prehistoric. This is one of the biggest surviving elmwoods in England.

East Anglia has some notable woodland moats: Gawdy Hall Wood (Norfolk), divided by an internal bank into two parts, each containing a moat; Hedenham Wood (Norfolk) and Burgate Wood (Suffolk), each with a huge ‘Hall Yard’ moat; Hockering Wood, with a moat in the middle of a big limewood. Some people evidently liked to live in the shelter of a wood. Woods may also contain ditched enclosures like miniature moats, for example in Hayley Wood, or Bonny Wood (Barking, Suffolk). Did woodwards’ cottages aspire to moat status?

Hillforts

Hillforts are embanked enclosures of the Iron Age. Some big ones, like South Cadbury in Somerset, enclosed permanent towns; others are interpreted as refuges for times of trouble.

Many hillforts, like Maiden Castle or Hod Hill in Dorset, are in grassland. Others, like Wandlebury near Cambridge, had trees planted in the eighteenth or nineteenth century. But many others are in ancient woodland or wood-pasture. Were the woods there when the hillforts were in use? If not, how much of the present woodland did the forts and their surroundings occupy? Two in Epping Forest, Ambresbury Banks and Loughton Camp, remind us of (they could even have inspired) Julius Cæsar’s statement that the Britons forted up in ‘impassable woods’.36 Neither has any visible field system attached.

The great hillfort of Welshbury, outside the Forest of Dean, with its triple fortifications, is in an ancient limewood. The limes, last coppiced in the 1930s, form huge stools and clonal patches, recognisable by differences in time of leaf-fall. The two biggest lime clones, one 40 × 39 feet (about 12 × 12 metres), both sit on (or emerge from under) the ramparts. Their size raises the question of their relation to the fort. Were they already there before it was built? A recent survey (which does not discuss the limes) reveals the further complication that the fort sits partly on an earlier field system.37

It might be thought that trees would shelter attackers and impede defence. But Dr David Morfitt drew my attention to the custom, in Continental fortifications, to plant the earthworks with trees that, when the time came, could be felled to form a defensive abattis that attackers would have to struggle through under fire.

Conclusions

Not all ancient English woods (or all tropical rainforests) have been woodland throughout the Holocene. Most of the big and some smaller wooded areas of medieval England contain evidence of Roman or earlier settlement and cultivation. However, it can seldom be shown that the whole of a medieval wood was non-woodland at an earlier period.

By the Iron Age, population had grown until it was no longer possible to cultivate the easier soils and leave the rest. People were tilling land later thought to be uncultivable. Was this was because of extreme pressure of population or because standards of what was cultivable were different then? Or was it a mistake, like modern attempts to cultivate deserts in America and Uzbekistan?

The second-largest wooded area in eleventh-century Essex lay east of Bishop’s Stortford. Although Domesday Book records woods here only roughly, in terms of swine, woodland must have predominated over several square miles. Most of it was grubbed out in the twelfth century, remained as farmland, and long afterwards became the site of Stansted Airport. The southern part remained as the woods of Hatfield Forest. In the 1990s investigations in advance of extending the airport found numerous settlements from Bronze Age to Roman in date. How much woodland survived through this earlier period of habitation is not known, but settlement had predominated over woodland for some of this time. Hatfield Forest has two known Iron Age sites, one with a small field system, and several other mysterious features which are unlikely to be natural.

An example pointing in the other direction comes from the coaxial fields of southeast Essex, an ordered landscape with a large hole in the middle containing the ancient woods of Hockley, Rayleigh and Hadleigh. Evidently there was a central block of infertile land that was left as woodland or heath. The woods have complex woodbanks that do not conform to the field system; in some there appear to have been two or three successive cycles of subdividing and embanking the woods.38

How many of the settlements and field systems recovered from under destroyed medieval woods could have been detected when the woods were intact? Are there unsuspected non-woodland features under surviving woods? These questions might have been settled in the 1950s and 1960s by surveying woods before and after they were grubbed out, to see whether they overlay archaeological features invisible in the intact wood. Alas, surveying practice developed too late, and woods were destroyed unrecorded. The compartment boundaries in Monks’ Park are visible both as soil marks in the destroyed wood and as banks and ditches in the remaining wood; but the soil marks also reveal faint, unrelated structures, probably Roman or earlier, which are confined to the part of the wood that was grubbed before recording began. Woods are now rarely destroyed, and opportunities no longer arise.

WOODLAND AND WAR

Battles in woods … are usually long and murderous.

LA GRANDE ENCYCLOPÉDIE, c.1882

Military remains tend to be less tidied-away and better preserved in woodland than elsewhere. They include practice trenches of World War I, sometimes dug into a pre-existing earthwork, with their characteristic zigzag or crenellated plan, changing direction every few yards. Along the old Lavenham railway (Suffolk) the medieval woodbank of Lineage Wood was pressed into service in World War II as part of a defence line supposed to keep invading tanks away from Cambridge.

Eastern England had more than a hundred military airfields in World Wars I and II. Their barracks, hospitals, ammunition stores, etc. were hidden in woods from enemy reconnaissance. After the war these structures rotted away (latrines being the last to go), but there are still remains. Stansted Airport began in 1942–3 as a bomber base; in Table Coppice, Hatfield Forest, are rows of iron stumps, the remains of hutments; the hard roads built to service them are still in daily use. Earl’s Colne airfield (Essex) resulted in bunkers in Markshall Woods, now adapted as bat shelters; in Chalkney Wood the huts are marked only as patches of nettles and other phosphate-demanding plants.

Woods have been used as strategic and tactical obstacles. The battle of Agincourt in 1415 is said to have been fought in a confined space between the woods of Agincourt and Tramecourt, but Azincourt has had no wood for at least 250 years, and the topography is now uncertain. Elizabethan accounts of warfare in Ireland make much of the difficulty of getting through woods. Having struggled through Irish woods on scree slopes, I am thankful not to have been wearing armour and under fire.

What of the effects of war on woodland? The military have at least temporarily destroyed woods, as along roads in Wales. Unusual quantities of timber have been consumed for military purposes or to sustain war efforts. And not only timber: Henry III when he went to war would order large quantities of hurdles, and down the centuries underwood was used to make gabions and revetments to trenches. But this should not be exaggerated. The period 1914–45 was unusually stable for ancient woods in England (apart from destruction by airfields), even though the amount of timber in many woods diminished.

In the nineteenth century European tacticians developed a system for turning woods into improvised forts, by creating an abattis of felled trees with defensive positions round the edge.39 This was tried in the Franco-Prussian War and World War I. It would leave archaeological traces, especially of the trenches and parapets recommended 60–100 feet (20–30 metres) inside the wood edges.

Generations have wondered at the devastated woods photographed in World War I, with the top shot off every tree. But woods quickly recover, as they do after hurricanes. Some shot-up woods and trenched and cratered ground were seized upon by the French and Belgian forest services for a spree of replanting in the 1930s. The effects of the War on the topography vary. Around Verdun, where a million men were slain in very wooded country, the woods are still much the same as on the Cassini map of c.1755, but both natural woodland and plantations have increased (the Forêt de Verdun) where the blood poured thickest. The woods that I have seen had returned to the appearance of a normal coppice-wood by the 1970s. The notorious Thiepval Wood on the Somme has recovered as a natural wood, but is still full of bodies, unexploded munitions, trenches and craters.40 In Flanders many small woods disappeared, but probably long after the war.

Wars can favour woodland by restraining unfavourable activities, especially pasturage. Parts of the Pindus Mountains were depopulated in World War II and the civil war that followed. When the people returned they found their lands seized by the Greek Forest Service on the plea that trees were now growing on them. Land rendered inaccessible by uncharted minefields has had the effect of protecting forests and allowing new ones to arise.

WOODLAND AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONSERVATION

Some archaeologists object to trees. Trees are supposed to promote erosion as raindrops coalesce on them and splatter the ground; this can be a useful corrective to the doctrine, common in other countries, that trees (and only trees) protect against erosion. Tree roots disrupt buried features. Tree-felling brings machinery that wrecks earthworks. When trees blow down their root plates tear up surface and buried features. For such reasons archaeologists in the 1960s destroyed the ancient wood on Llanmelin hillfort not far from Welshbury, losing any prospect of ever understanding the relation between the trees and the hillfort.

If trees take over grassland sites the ecology as well as the archaeology is damaged, which should be opposed by both kinds of conservationist. Cambridgeshire Wildlife Trust has spent many years on the laborious task of reversing the invasion of the great earthworks of Devil’s Ditch and Fleam Dyke.

With ancient woodland the trees may well be part of the archaeology, like elms at Buff Wood and Overhall Grove. At Welshbury the ramparts are in excellent condition despite centuries of coppiced limewood; the state of the underground features is unknown, but any damage by roots will have been completed long ago. The conservation of the archaeology depends on suitably managing the trees. If lime is allowed to grow up to tall trees, this will indeed result in windblow at the next big storm. As has been shown at Overhall Grove, timber can be removed without damaging the earthworks by attention to detail, such as not using machines in wet weather and filling ditches temporarily with logs.

The Forestry Commission has recently surveyed its woods in the east Midlands for archaeological features, entering the results on constraint maps that identify areas out of bounds to certain types of operation. This should set an example, ending the tradition among archaeological and biological conservationists of not talking to each other, even when they war against the same foes.

Footnotes

fn1 A hint that points in this direction is the clonal distribution of lime. If limes habitually blew down, they ought to have taken root along the fallen trunk, giving rise to a linear clonal patch. I have been unable to find such patches.

fn2 For the Ruddiman hypothesis, this happened on a world scale so vast as to produce a remission in the rise of atmospheric carbon dioxide and in global warming.