Having explicated the context in which small development non-profits operate, and examined the ways they conduct, utilise, and perceive evaluation, this final chapter unpacks the point of evaluation in small non-profits against the three concepts outlined in Chapter 3: community development, evaluation, and evaluation utilisation. This chapter ascertains whether evaluation could fulfil donor-driven expectations and provide more relevant and useful approaches to evaluation for small non-profits than those promoted by the evaluation orthodoxy. These conclusions support the key assumptions outlined in Chapter 1: (1) Development non-profits aspire to enact their stated community development values and commitments, and evaluative processes should support and enhance these aspirations. (2) Small non-profits are increasingly expected to conduct rigorous evaluations. (3) The existential worth of evaluation is bound to its utilisation. Therefore, without utilisation of some description, this book considers evaluation pointless.

In Chapter 1, I argued that fulfilment of these three assumptions constitutes evaluative success for community development non-profits. After exploring the success, or otherwise, of current approaches to evaluation in small non-profits in the first half of this chapter, the second half draws on the literature and practitioners’ constructed knowledge around useful and pragmatic ideas to explicate a new approach to evaluation, which is sensitive to the advantages, constraints, and values of these organisations.

(Re)Working Evaluation to Align with Community Development

Supporting the first assumption underpinning this book, Chapter 4 established that small development non-profits aspire to enact their stated community development values and commitments. However, as noted in Chapters 5–7, the extent to which the evaluative processes at play support and enhance these aspirations is less clear. This section uses the findings, and elements of evaluation and community development drawn from the literature in Chapters 2 and 3, to determine how aspects of evaluative practice in these organisations align with community development expectations. By distilling elements of evaluation that work with or against community development, this section highlights practices that are possibly more or less useful, meaningful, and purposive for evaluation’s primary intended users: non-profit practitioners.

Non-profits are struggling to fulfil increasing demands for evaluation (Bach-Mortensen & Montgomery, 2018; Carman & Fredericks, 2010; Shutt & McGee, 2013), a task made more difficult due to the nature of their work whereby impacts are often long-term, effectiveness is subjective, and attribution is complex. Whilst scrambling to prove their effectiveness using methods expected by donors, non-profits are being criticised for a lack of downward accountability, failing to critically reflect on their practice, being too professionalised, and sycophantically responding to donors’ commands (Edwards & Hulme, 1995; Ramanath, 2014). While these criticisms may be particularly applicable to larger non-profits, practitioners in this study identify with the first two of these criticisms, expressing a desire to focus more strongly on community recipient-centred accountability and on enhancing their critical reflection. In terms of the last criticism, case study non-profits face difficult choices and trade-offs between fulfilling donor demands and staying true to their community development values.

Pulled in two directions, case study non-profits are unable to devote full commitment to either upward or downward accountability. They, along with others in the sector, report that evaluation mechanisms have resulted in less time with community recipients and more time gathering and compiling data. In response to these pressures, some non-profits have found the need to game the system through falsification, reclassification, prioritising actions that link to predetermined indicators regardless of value to community recipients, and other strategies which result in data inaccuracies and negate the point of doing the evaluation in the first place (Lowe & Wilson, 2017). Practitioners comment that this is sometimes the only option due to busy roles in small non-profits and short evaluation timeframes. Instead of an inclusive discursive process for reflective thought and growth, evaluation becomes, in the words of one practitioner in South-East Asia: ‘Quick! Gotta churn out something!’ Playing the game is no longer a viable option as the demand for results is becoming so encompassing that it is diminishing organisations’ ability to respond effectively and prioritise accountability to community recipients.

Worlds apart?

Evaluation orthodoxy | Community development | |

|---|---|---|

Positivist/post-positivist | Metaphysical | Interpretivist/phenomenological |

Science-based evidence | Experience-based evidence | |

Considered objective | Subjective | |

Considered value-free | Context-sensitive | |

Methodological | Operational | Social/participatory |

Deductive | Inductive | |

Controlled | Real world | |

Linear/logical | Iterative/cyclical | |

Reductionist | Complex | |

Pre-determined indicators | Emergent social change | |

Outcomes/impacts | Process/transformation | |

Top-down | Power | Bottom-up |

Professional | Empowering | |

External experts | Community experts | |

Technical knowledge | Local wisdom | |

Extracting | Capacity building | |

Objectification | Rights-based citizenship | |

Upward accountability | Downward accountability | |

Individualist | Collectivist |

The rest of this section unpacks the table presented above, beginning with a discussion of this clash of values at the metaphysical level, which notes that the evaluation orthodoxy offers ‘a very narrow interpretation’ of evidence supported by methodological individualism, neoliberalism, and new public management (NPM) (Schwandt, 2005, p. 96). Measurement is one of NPM’s ‘key planks’, resulting in a tenacious emphasis on performance management and accountability, as in, achieving promised results (Lowe & Wilson, 2017, p. 981). The top-down and cognitively fixed approach to evidence aligns with this neoliberal NPM paradigm which privileges the attainment of profit and values professionalism, competition, and individualism. As such, the evaluation orthodoxy rests on a philosophical foundation of realism, rationalism, positivism, and empiricism, a paradigm antithetical to interpretivist-aligned community development as it objectifies and ignores the complexity of human phenomena. Nonetheless, as the neoliberal paradigm prevails in most ‘developed’ world regions (where most bilateral and multilateral donors, large philanthropic foundations, and large international non-profits are headquartered) it is unsurprising that the development sector increasingly adopts notions of the evaluation orthodoxy, as was observable in the case study non-profits.

The hierarchy of evidence and its associated branches have been thoroughly critiqued throughout the literature of multiple disciplines (e.g. Archibald, 2015; Lowe & Wilson, 2017; Simons, Kushner, Jones, & James, 2003). However, a strong residual internalised belief in the truth of the hierarchy endures (Chouinard, 2013). This was evident in case study non-profits’ deference to ‘experts’ and extremely limited use of participatory evaluation techniques in preference to practitioner- or ‘expert’-led methods.

Most would agree that policies and practices should draw on the best available evidence. However, the evaluation orthodoxy has co-opted and attributed a specific meaning to the term ‘evidence’, as objective, rational, and ‘unproblematically separable from the scientists who generate it and the practitioners who may use it’ (Greenhalgh, 2018, p. 13). Dominant understandings within the evaluation orthodoxy specifically value ‘quantitative evidence gathered through “rigorous” research or evaluation designs’ (Archibald, 2015, p. 138). As such, this perpetuates a positivist view of scientific research evidence as factual and other forms of evidence as weaker and dismissible. This outlook is particularly problematic as it provides normative policy, operational, and evaluation packages (which may have demonstrable efficacy in controlled settings), for replication in real-world settings without consideration of context. Practitioners highlight the difficulties surrounding this as, adapting an evidence-based project to more appropriately suit the context results in the project no longer being ‘evidence-based’ as the controlled setting has changed.

Internalised belief in a hierarchy of evidence provides rationale for the acceptance and influence of ‘evidence-based’ evaluation approaches that are not always appropriate for context and purpose. As stated by Crotty (1998, p. 28): ‘The world perceived through the scientific grid is a highly systematic, well-organised world. It is a world of regularities, constancies, uniformities, iron-clad laws, absolute principles. As such, it stands in stark contrast with the uncertain, ambiguous, idiosyncratic, changeful world we know at first hand’. In the case study non-profits, this internalised privileging of certain ways of knowing has resulted in the adoption of irrelevant evaluation approaches, demonstrated by the very low instrumental use of external and internal formal interval-based evaluations and practitioners’ stated claims regarding their irrelevance. This is despite the existence, discussed in Chapter 2, of multiple participatory evaluation approaches developed just for them and their ‘uncertain, ambiguous, idiosyncratic, changeful world’.

As the positivist mindset is being pushed from the top down, with the locus of power in the hands (and bankrolls) of donors, community organisations and the people they work with have little or no power over these fundamental discourse-driving decisions. Practitioners mention that they need to develop their critical thinking and downward accountability, but are in thrall to the ‘technologies of power’, artefacts of the evaluation orthodoxy that require ‘obedience rather than independent and above all, critical thought’ (Eyben, 2013, pp. 8–9). Similarly, Cheek (2007, p. 100) argues that ‘methodological fundamentalism’ has shaped understandings of evidence which ‘are colonized by discourses such as the evidence-based movement’.

The evaluation orthodoxy with its evidence-based audit culture, outcomes-based performance management, results-based accountability, best practice directives, and ‘gold standard’ of evidence exudes infallibility and precision. Practitioners suggest that these positivist approaches could be valuable in some cases, depending on the evaluand and the evaluation purpose. The concern highlighted by practitioners and the literature is that the orthodoxy’s internalised legitimacy eclipses other ways of knowing and diminishes the voice of marginalised groups (Cheek, 2007; Lennie & Tacchi, 2013; Patton, 2015). This is important to unpack as, ‘Treating ideas such as evaluation and accountability as self-evident and non-problematic is asking for trouble in an environment where neo-liberalism and managerialism are increasingly accepted as the conventional wisdom’ (Ife, 2013, p. 174). The evaluation orthodoxy promotes a myth of certainty, failing to recognise that all forms of inquiry and evidence are value-laden, open to interpretation, and maybe inherently imperfect and ambiguous. The normative approach of the orthodoxy can directly contravene community development notions of context-sensitivity, community expertise, and empowerment, undermining the everyday work conducted in small development non-profits. The focus should be on what is methodologically appropriate rather than on ranking methods according to a controverted and often irrelevant hierarchy of evidence.

The second section of the ‘Worlds apart’ Table 8.1 presents the operational level split between the orthodoxy’s notion that subjects can be controlled and measured with accuracy, against community development understandings of real-world complexity, fluidity, and change. Wadsworth (2011, p. 154) argues that the myth of certainty promoted by the evaluation orthodoxy is ‘a false sense of certainty’. Practitioners mention this when discussing how they use evaluations to ‘prove’ their effectiveness. While the idea of simple and coherent outcomes that prove effectiveness would be wonderful, the innumerable variables, interactions, and well-being of people and societies cannot be boiled down to a statistic. Therefore, a certain world is ‘impossible’ and a reductionist approach cannot conceivably ‘reflect the reality of community life’ (Ife, 2013, p. 175). This notion is supported by practitioners who discuss the need for in-depth, ethnographically inspired, participatory evaluation methods. This extends credence to practitioners who champion the use of complexity and systems thinking concepts to inform a more realistic picture of events and change-making processes.

Similarly, the often reductionist, non-participatory, deductive, and linear tools utilised by the evaluation orthodoxy can undermine community development values. Logical frameworks, program logics or logframe matrices, are commonly developed by case study non-profits and other actors in development and beyond. They provide a stepwise cause-and-effect chain based on assumptions of program consequences. They help organisations develop expected outcomes and performance indicators to measure the achievement of outcomes. These tools and the indicators and outcomes encased within them are predominantly developed without community recipient involvement, and are only able to capture predetermined, intended outcomes with unfounded assumptions regarding attribution or contribution. This means they can only provide a simplistic account of whether the intended outcomes occurred, largely ignoring the complexity of social change that surrounds these small, rigid achievements. Green (2016, p. 12) clarifies the difficulty of using a linear model to assess change in complex systems using the analogy of raising a child: ‘What fate would await your new baby if you decided to go linear and design a project plan setting out activities, assumptions, outputs, and outcomes for the next twenty years and then blindly followed it? Nothing good, probably.’ Suggesting that social programs occur in (or can be crammed into) a controllable, linear vacuum conceptualises evidence as ‘a narrow discourse in which the “how” of context and process is ignored’ (Eyben, 2013, p. 17).

This linear thinking ignores the reality of the real world in which non-profits operate. Variations of logical frameworks, such as theory of change models, may offer a more appropriate tool for community development organisations due to their flexibility and ability to incorporate complexity. A minority of practitioners suggest the use of theory of change to explore the causal linkages and drivers of change, which may include psychological, sociological, political, and economic factors. Theory of change models continue to be less utilised than logical frameworks and are hindered by a lack of conceptual clarity to separate the two models (Peta, 2018; Prinsen & Nijhof, 2015). While this can result in a ‘theory of change’ becoming a logic model with a different name, practitioners recognise its potential as a tool for deep reflection and enhancing strategic direction and clarity.

Another aspect of difference manifests in the reductionist nature of the evaluation orthodoxy versus the complex nature of community development. The further up the evidence pyramid one goes, the more reductionist the approach, an approach that simplifies and distorts real-world settings to the extent that they are no longer based in reality (Butler, 2015; Guba & Lincoln, 1989; Lowe & Wilson, 2017). As highlighted throughout this book, complexity is inherent in the work done by small development non-profits, as it is to non-profits offering social programs regardless of size. Specifically, practitioners recognise complexity in relationships with and between themselves as workers and between recipients and their communities and the wider norms and mores of their cultural and political settings. They identify complexities within individuals that negate reductionist forms of evaluation that barely scratch the surface of meaning. While emphasis on the importance of context-sensitivity and complexity concepts are common throughout evaluation literature (Patton, 2011, 2012; Wadsworth, 2010; Walton, 2014, 2016), this is often ignored in practice with the disconnect between reductionist evaluations of complex programs remaining the elephant in the evaluation literature room. Lowe and Wilson (2017, p. 997) suggest that this makes evaluation a farcical ‘game’ which ‘exists in two separate dimensions: the dimension of simplified rules, and the complex reality of life…This means that the game does not “make sense” but still staff [and evaluators] must learn to play it well’.

Rather than waste small non-profits’ limited resources playing an evaluation game, practitioners suggest alternatives to standard evaluation that align with community development values, which will be discussed later in this chapter. Within this reimagined framework, practitioners mention their desire for community-driven identification of indicators and outcomes. However, donor-driven evaluation expectations and resource limitations hinder adoption of bottom-up participatory approaches, which, while time-intensive, could contribute to organisational mission and objectives. Instead, in all but two instances, case study non-profits base their performance on indicators and outcomes determined from the top down. As well as undermining community development approaches to empowerment and bottom-up practice, performance indicators are limited in their utility as they fail to provide background information to help users understand why the results are as they are or clarify how they could be improved.

Further, the shallow typology of ‘outcomes’ in standard evaluation demonstrates a focus on ends (outcomes) guided by linear logical frameworks rather than the community development focus on means (process) guided by intricate and complex theories of change.1 While outcomes-based evaluation is a strong focus of the contemporary evaluation climate, these ‘outcomes’ are often abstracted benchmarks aimed at assessing one small part of a person’s life, which are not attributable to an intervention anyway due to incalculable variables. In many cases, including within the case study non-profits, outcomes are developed in accordance with their measurability against a set of predetermined indicators, most likely devised by people other than the community recipients whose desired outcomes have been assumed. As such, Ife (2013, p. 179) suggests that this ‘obsession with outcomes’ is ‘part of the problem, and they are unlikely to play much part in the solution’. Rather than automatically agreeing with the dominant discourse, this highlights the need to dissect assumptions surrounding these ideas and, particularly, to consider them against community development values to assess whether this normative evaluation focus is one to which community development non-profits wish to align.

The final section of the ‘Worlds apart’ Table 8.1 examines the overarching split between notions of power and who should wield it between the evaluation orthodoxy and community development. As well as being antithetical to community development values, practitioners identify that acceptance of top-down approaches to evaluation reduce capacity for creativity and deep introspection. The increasing adherence to neoliberal ideas of bureaucracy, managerialism and short-term, unstable funding undermine community development’s ability to deeply critique itself (Ledwith & Springett, 2010). Demonstrated by the short journeys formal evaluations take from case study non-profits to their donors, evaluation has become about upward obedience rather than about critical (evaluative) thought (Lennie & Tacchi, 2013).

Practitioners highlight that their organisations are subject to accelerating expectations to prove their effectiveness according to top-down notions of proof and evidence. Practitioners feel powerless to challenge these expectations, identifying that they operate in a climate where, ‘Those who produce the appropriate data are rewarded, those who fail to do so are punished’ (Lowe & Wilson, 2017, p. 994). In this way, artefacts of the evaluation orthodoxy, such as logical frameworks, become neoliberal tools that give donors further power and control over non-profit activities. Practitioners in Chapter 4 identified that the small size of their organisations increased their ability to choose donors with matched values who provide space for them to pursue bottom-up agendas. The fact that they still identify this lack of power around evaluation suggests that larger non-profits may operate in even greater states of bondage to donors surrounding evaluation expectations.

Observation and practitioner statements in the case study non-profits capture a lack of user buy-in surrounding externally expected evaluation approaches and tools. This situation severely limits evaluation utility and utilisation, demonstrated by the low-use of formal evaluation in the case study non-profits, despite these being rigorous and well-presented. In this regard, a technically precise evaluation determined from the top down and conducted by outsiders is unlikely to hold much value for non-profit practitioners and community recipients beyond fulfilment of upward accountability demands. This claim resembles arguments in development theory that privilege bottom-up community participation as crucial for sustainable and empowering social change, as highlighted in Chapter 3.

The assumption that evaluation is conducted by external evaluators is ‘almost always’ implied in the evaluation literature (Conley-Tyler, 2005, p. 3). Practitioners concur that their donors prefer external evaluation and that internally driven evaluation is considered less rigorous. This is despite many appraisals extolling the virtues of internal evaluative efforts (Baron, 2011; Love, 1991; Rogers & Gullickson, 2018; Rogers, Kelly, & McCoy, 2019; Sonnichsen, 2000; Volkov, 2011; Volkov & Baron, 2011; Yusa, Hynie, & Mitchell, 2016). The notion of an external expert is contradictory to the shared and non-directive styles of leadership discussed in Chapter 3 as vital to community development facilitation. Community development posits that if external expertise is required, the demand for it should come from the bottom up and be driven by the community themselves wherever possible (Ife, 2016; Twelvetrees, 2017). Additionally, this expertise should be predicated on a commitment to upskill and empower rather than to conduct ‘research on’ and extract (Cheek, 2007; Cooke, 2004; Smith, 2012). While external upskilling and empowerment is mentioned as a process outcome of evaluation in two of the case study non-profits, others (as previously quoted in Chapter 5) highlight that external evaluators are simply ‘coming in and doing their stuff and then taking it away’.

Embedding evaluation in organisational processes is discussed throughout the evaluation literature (Cousins, Goh, Clark, & Lee, 2004; Greenaway, 2013; Labin, 2014; McCoy, Rose, & Connolly, 2013), suggesting scope for evaluation to fit within process-focused community development and aligning with the informal evaluative processes occurring in non-profits. While informal evaluative processes are embedded in case study non-profits, embedment is not occurring as part of their formal interval-based evaluations. Formal evaluations in case study non-profits are conducted by a cloistered staff member or by an external expert who extracts the data to external institutions for analysis and then distributes it upward, an approach deplored by researchers and practitioners championing Indigenous research methods (Battiste, 2007; Chilisa, 2012; Smith, 2012). Ledwith (2011, p. 80) adds that, ‘It is ideological hypocrisy for community development to resort to research methods that are based on unequal, culturally invasive relationships’. Additionally, extractive and context-deficient evaluation conducted on community recipients will be of little value to organisational learning and recipient needs.

The final disconnect between the evaluation orthodoxy and community development discussed here is accountability. Edwards and Hulme (1995, p. 6) highlight that ‘Performing effectively and accounting transparently are essential components of responsible practice’, but accountability to whom and effectiveness as determined by whom? In the evaluation orthodoxy, accountability is consistently directed upward with less recognition given to the importance of authentic downward accountability. Highlighting the superficiality of non-profit accountability, Edwards and Hulme (1995, p. 13) define this as a ‘tendency to “accountancy” rather than “accountability”’. Examination of evaluation utilisation in case study non-profits demonstrates this upward accountability with formal evaluation predominantly manufactured for and distributed upward to donors. However, practitioners decry this practice and desire a change that refocuses their accountability downward and challenges the ‘frequent and incessant demands of upward accountability’ (David & Mancini, 2005, p. 1). Further, practitioners voice a desire to recognise everybody as an evaluator with value to add, highlighting that community-driven evaluation and bottom-up accountability could more appropriately support organisational learning and improvement while simultaneously helping them work towards their community development aspirations for empowerment and sustainability.

Ife (2013, p. 174) confirms that: ‘Community development actually stands against trends such as individualism, managerialism and neo-liberalism, and it is these trends that have helped to shape notions of “accountability” (and other concepts) in ways that perpetuate and exacerbate inequality, injustice and oppression’. If community development non-profits are accepting top-down conventional wisdom as truth and best practice, then this ‘wisdom’ is being accepted from the same powerful dominant forces and structures that community development professes to hold to task.

Rather than becoming obedient puppets or undercover rebels content to game the system, these contentions between community development and evaluation highlight the importance of retaining a critical mindset and unpacking organisational values against contending evaluation approaches. The following section examines ways in which evaluation standards support or hinder current evaluative practices in small development non-profits.

Ensuring Rigorous Community Development Evaluation

This section focuses on the second and third assumptions that underlie this book. The assumptions presuppose that evaluation needs to be rigorous and utilised. While rigour is context-sensitive (Patton, 2015), in this book rigour is broadly aligned with the Joint Committee program evaluation standards introduced in Chapter 3. This section examines the findings from this research against the first four evaluation standards (utility, feasibility, propriety, and accuracy) to unpack the success of current evaluation practice in the case study non-profits according to these assumptions.

Low-use and non-use of evaluation has been identified as an issue of concern for decades, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3. Those within the evaluation discipline have sought to rectify the utilisation problem with the Joint Committee utility standards adding to this pursuit by outlining aspects of practice to facilitate utility (Yarbrough, Shulha, Hopson, & Caruthers, 2011). The utility standards expect evaluation to have a purpose negotiated with stakeholders, to communicate in a timely manner and pay attention to stakeholders, and to be aware of negative consequences. According to the standards, evaluations should be relevant and meaningful to primary intended users and should engage qualified evaluators with credibility. The utilisation-focused concepts, introduced in the conceptual framework, build on these standards to insist on utilisation rather than simply utility (Patton, 2012). These highlight the need to identify and engage primary intended users and collaboratively develop the purpose, determine appropriate methods, and interpret evaluative data. Additionally, utilisation-focused evaluation expects evaluators to hold responsibility for effective dissemination and utilisation of results (Patton, 1988).

Examining evaluation in the case study non-profits through a utilisation-focused lens illuminates disconnects between non-profits’ evaluation aims and practice. Practitioners highlight that the purposes of evaluation are for improvement, to check on effectiveness, and for accountability. However, in practice only eight per cent of external and internal formal evaluations in the case study non-profits are used for improvement, as discussed in Chapter 6. Further, in two-thirds of these cases, practitioners were planning to make the changes recommended by the evaluation prior to receiving the evaluation results. In terms of effectiveness, practitioners have reservations about the accuracy of formal evaluations, a concern that impedes evaluations’ ability to determine effectiveness in a manner deemed acceptable and trustworthy to the primary intended users, an issue discussed further on in this section when I focus on the Joint Committee’s accuracy standard. Formal evaluations are used for accountability as they are invariably sent upward to donors. However, practitioners are cognisant that they are not paying sufficient attention to downward accountability, as mentioned in the previous section. Additionally, they are unsure as to whether the evaluations sent upward are utilised beyond the action of emailing them to donors.

Conversely, ninety-two per cent of practitioners identify informal evaluative activities as being of instrumental use, specifically for assessing effectiveness and for helping the organisations improve. These activities have less focus on accountability although they are utilised for both upward and downward accountability in some instances. In all three forms of evaluation (external, internal, and informal), practitioners identify that instrumental use is driven by non-profit staff members.

Formal evaluation is identified by practitioners as being largely irrelevant and meaningless, an issue demonstrated in practice in the case study non-profits as negatively impacting evaluations’ utility and utilisation. Practitioners identify this lack of relevance as stemming from perceived expectations of evaluation rigour and objectivity, and evaluators with differing values who did not accurately capture the evaluand. Further, case study non-profit staff have little involvement in formal evaluation processes resulting in limited user buy-in or ownership, another barrier to utilisation. Practitioners comment on the strong power differentials between them and their donors that limit their ability to negotiate alternative options. As the case study non-profits drive informal evaluative processes for their own needs, these activities have high relevance and meaningfulness to the primary intended users, resulting in their high utilisation. Additionally, as these informal processes are not mandated, they are developed as needed and with context-sensitivity by organisations with an appetite for learning and critical thought.

While substantial utilisation of formal evaluation in the case study non-profits was not immediately obvious, conceptual use is a common outcome of inquiry that is likely to occur throughout evaluative processes. In Chapter 6, I surmised that conceptual use may be the main ‘point’ of formal interval-based evaluation. However, while conceptual use is important, its imprecise nature is indicative of Patton’s (2007, p. 104) complaint that, instead of clarifying use, ‘we are becoming vaguer and more general’. Further, it is unknown whether the quantity or quality of conceptual use in the case study non-profits is greater in formal or informal evaluation. It is likely to occur in both, but its slow accretion and ambiguous existence hinders attempts to measure its influence. Presuming that conceptual use is important but ubiquitous, this type of use should not offer different forms of evaluation any advantage. Rather, this emphasises that advantage should be weighed by instrumental use as a priority, and process use to enhance instrumental use, with conceptual and symbolic use as by-products; a utilisation protocol that corresponds with the stated uses of informal evaluation in the case study non-profits.

While evaluators conducting formal evaluations in the case study non-profits likely attempt to negotiate purposes, include stakeholders in decision-making, and conduct evaluations with the aim of producing relevant and meaningful reports, practitioners consider that very few of these succeed. Practitioners clarify that evaluators should have matched values and allocate sufficient time to work in a participatory and bottom-up manner to understand and include non-profit staff and community recipients in meaningful evaluative processes. This suggests that evaluation utility and utilisation in small development non-profits can be maximised through inclusion of community development values that favour inclusive participation, local ownership, cohesive relationships, shared decision-making, and non-directive leadership; elements of practice practitioners feel more important than methodological precision (Chapter 7). The emphasis on local ownership links to a tenet of utilisation-focused evaluation that places responsibility for utilisation on the evaluator (Patton, 1988, 2012). When everyone is the evaluator with ownership over the evaluation, shared responsibility can ensue.

Feasibility, the next Joint Committee standard, is assessed according to evaluations’ ability to make prudent and effectual use of resources, cause minimal interference to organisational operations, and to be practical, viable, and context-sensitive (Yarbrough et al., 2011). While the findings related to the other evaluation standards in this section are mostly split between formal and informal evaluations, the findings related to feasibility are mostly split between formal evaluations conducted by external experts, and evaluations conducted by non-profit staff—whether formal interval-based internal evaluations or informal evaluations.

A main concern regarding external evaluation is the high cost that practitioners feel is unrepaid in value. In Chapter 5, practitioners highlight that they struggle to afford external evaluation as sufficient factoring into funding agreements is rare. The thought of expenses associated with external evaluation was enough to firmly dissuade three non-profit directors from conducting external evaluation, citing that they would rather spend the money on programs. This reconfirms the notion of non-profit practitioners as ‘doers’ who are less interested in ‘time-consuming and costly evaluations’ (Ebrahim, 2005, p. 65). On rare occasions when the case study non-profits scrape together enough funds, expectations are commensurate with the hardship the organisations endure to undertake such a costly venture. Practitioners indicate that the high cost may be acceptable if resulting evaluations affect significant improvements in programs and organisational capacity. However, as highlighted in Chapter 6, the research undertaken for this book shows minimal utilisation of external evaluations.

Economically, the cost–benefit scenario for external evaluation is mostly negatively unbalanced in the case study non-profits, suggesting that ‘arms-length funding of small NGOs may be more cost-effective’ than models that expect rigid measures (Copestake, O’Riordan, & Telford, 2016, p. 159). External evaluation diminishes the case study non-profits’ finances with minimal benefit from the final product (Chapter 6). Further, practitioners comment that external evaluation consumes additional organisational resources, most notably staff time due to tendering and commissioning the evaluation, informing the evaluator, and engaging as evaluees (Chapter 5). While internal forms of evaluation are usually more cost-effective, both internal and external interval-based formal evaluation drain staff time. However, this is minimised in internal evaluation as there is no need to commission an evaluator or help them get to know the organisation, as is necessary for external evaluators. Alternatively, practitioners suggest that informal everyday evaluation does not deplete financial or personnel resources as it is embedded and not an additional chore. They feel that everyday evaluation strengthens practitioners and programs in line with their values, providing an instant benefit through process use. Similar to participatory evaluation introduced in Chapter 2, everyday evaluation is part of community development practice.

Linked to staff time, formal evaluation can be disruptive to practitioners, particularly if the evaluator needs to interview them or observe them in practice. If the evaluator is conducting experiments or other research on community recipients, this has greater ramifications for disturbing and even inadvertently sabotaging non-profit work. Evaluators regularly attempt to limit this interference, as mentioned by the evaluation consultant in Chapter 5 who discusses getting program facilitators to distribute surveys rather than an evaluator coming in and disrupting the program. My observations at one urban Australian non-profit, presented in Chapter 5, showed potential disturbances of the hiring process alone, with staff struggling to find an evaluator who would conduct the evaluation for the minimal funds they had at hand.

Another aspect of feasibility is subject to evaluations’ practicality. This highlights the need for evaluation to be practical for all stakeholders and for practicalities to be weighed against beneficence, utility, and accuracy (Yarbrough et al., 2011). Using a pragmatic lens to assess practicality demonstrates that formal evaluation faces numerous issues for the case study non-profit staff, such as interference and cost discussed above, which informal everyday evaluation ameliorates. However, as this book focuses on non-profit practitioners and organisational processes, the practicality of formal and informal everyday evaluation for other stakeholders requires further investigation.

Viability is a key aspect of feasibility. This book suggests that, for evaluation viability, the three assumptions introduced in Chapter 1 are essential. Document review in Chapter 5 revealed that the formal evaluations, particularly the external evaluations commissioned by the case study non-profits, are of adequate quality and rigour. In this, these evaluations are methodologically viable. As the informal evaluative processes are often ad hoc and unsystematic, these bear less methodological rigour. These findings suggest that formal evaluation meets the second assumption that small non-profits need to deliver rigorous evaluations, while informal evaluation requires further development to meet this success indicator. However, formal evaluation in the case study non-profits fares more poorly on the first and third assumptions as these evaluations are largely divorced from non-profits’ community development values as well as suffering from underutilisation. Conversely, informal everyday evaluation is better utilised and aligned to non-profit values. The first assumption is particularly salient as values are central to feasibility.

Finally, adequate engagement of stakeholders is vital to feasibility, necessitating context-sensitive and inclusive practices. Practitioners wish to develop their processes of downward accountability and inclusion of community recipients in all forms of evaluation, but remark that they are strongly engaged in informal everyday evaluation with recipients. Practitioners do not raise any problematic instances with engagement between stakeholders in any internal or informal everyday evaluations. Instead, they provide examples of respectful and inclusive relationships, such as when community recipients at an urban Australian drop-in centre gathered to deliberate and make the final decision between two options for the organisation’s new premises. However, practitioners highlight numerous concerns regarding staff and community recipient engagement with external evaluation and evaluators. While there are stories of positive relationships between non-profit staff and external evaluators, these are dwarfed by discontents. Practitioners often feel their engagement with external evaluators was perfunctory, while evaluators’ engagement with community recipients was sometimes inappropriate or non-existent. Two examples previously detailed in Chapter 7 are the overly long surveys that fatigued recipients in a suburban Australian non-profit, and the external evaluators who feared for their safety so would not speak with recipients (female prostitutes) despite staff requests and reassurances at an urban Australian non-profit.

Overall, formal, specifically external, evaluation appears largely unfeasible for small development non-profits in terms of cost-effectiveness, disruption, practicality, viability, and context-sensitivity. Equally, internal and informal everyday evaluation is largely feasible. The main aspect of feasibility where informal evaluation falls short is its viability in terms of rigour. This suggests that building rigour into informal evaluative processes is necessary for progressing feasibility for this form of evaluation.

The Joint Committee’s evaluation standard of propriety expects that evaluators behave appropriately and morally through engaging in respectful, transparent, and clear processes that ensure inclusive, responsive, and negotiated communication and decision-making (Yarbrough et al., 2011). This includes upholding ethical responsibilities and human rights in evaluative practice. Evaluation ethics is a contested space in the case study non-profits. Practitioners feel ethics is under control, as external evaluators tend to have university affiliations that give them an aura of credibility. Despite this, practitioners raise issues where they feel external evaluators acted in breach of ethical practice. Conversely, none of the internal or informal everyday evaluations reviewed or observed in the case study non-profits had formal ethics approval and practitioners state that sufficient consideration of ethical ramifications is rare, as discussed in Chapter 5.

Practitioners mention that small non-profits can be so overwhelmed by the idea of evaluation and accompanying ethical dilemmas that they avoid conducting evaluative activities, especially ones that would entail discussions with community recipients. Festen and Philbin (2007, p. 6) comment that the ‘pressure to evaluate and the misconceptions about what evaluation entails can lead many smaller groups to forego the effort altogether, assuming it requires specialized skills or rigor beyond their capacity.’ Hatry, Newcomer, and Wholey (2015, p. 819) compound this fear confirming that ‘Virtually all evaluations will be subject to formal requirements to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects’. While formal ethics approval is rarely necessary for small-scale evaluative consultations with intent to prove and improve programs for dissemination within the immediate stakeholder group (NHMRC, 2014), it is good practice to subject inquiry with humans to critical ethical reflection. Practitioners with doctoral degrees note that ethical considerations are often under-thought in small non-profit contexts and suggest this could be a space for capacity development.

Ensuring beneficence to participants is one of the key ethical considerations of any research (NHMRC, 2007a, 2007b; Persson, 2017), including evaluation (NHMRC, 2014). In the case of small development non-profits, this expects that evaluation benefits practitioners and community recipients in a manner that outweighs the risks and discomfort of the evaluation; ‘discomfort’ including financial and time loss as well as emotional and social discomfort. There are no glaring cases of ethical breaches in the evaluations reviewed for this book with discomfort (apart from possibly financial loss related to external evaluation) appearing minimal. However, the findings presented in Chapter 6 show that utilisation of formal evaluations was also minimal. This suggests that the benefit of the formal evaluations was either equal to or less than the discomfort it caused the organisation and evaluation participants. Practitioners report no discomfort associated with informal everyday evaluations as these processes are linked to activities that are intended to be of immediate benefit to participants (whether practitioners or community recipients). Additionally, these informal activities are highly utilised, as demonstrated in Chapter 6, tipping the balance strongly towards benefit with minor risk or discomfort.

In terms of respectful and inclusive relationships, practitioners raise cases where they feel external evaluators did not take their opinions or suggestions on board, similar to my experience with external evaluators recounted in the author note at the beginning of this book. Further, practitioners mention instances where external evaluators, probably inadvertently, disrespected their organisation, program, or recipients. This includes cases mentioned in Chapter 7 where external evaluators’ over-professionalised manner prevented their ability to connect or relate to practitioners and community members, and when external evaluators diminished the importance and value of programs by offering ‘quick and dirty’ evaluations. There were no instances noted throughout the document review, observations, or interviews, of internal evaluators being perceived as anything other than inclusive and respectful. While external evaluators are well versed in the importance of stakeholder relations, practitioners’ perceptions highlight that external evaluators’ rapport-building attempts are not always positively received. The potential for disconnect between professional external evaluators and small non-profits may be greater than in larger non-profits due to smaller organisations’ tendency to be less professionalised and closer to the communities with whom they work, as outlined in Chapter 4.

The fourth evaluation standard identified by the Joint Committee surrounds evaluation accuracy. An ‘evidence-based mania’ (Schwandt, 2005, p. 96) has provided the idea that stakeholders can accurately evidence effectiveness. This ignores the idea that ‘not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted’ (Cameron, 1963, p. 13).2 Regardless, accuracy is key to effective evaluation as inaccurate data can lead to misinformation, inefficiencies, and suboptimal management. Additionally, inaccuracy, or perceived inaccuracy, can have significant repercussions on evaluation utilisation. Due to the interpretivist character of development practice, perhaps notions of credibility and trustworthiness are more suitable than notions of accuracy for small non-profit evaluations. Again, this raises a benefit of matched values between evaluators and non-profits as philosophical and practical ideas around what is accurate can differ if one party is focused on construct validity and the other on trustworthiness.

Accuracy in evaluation refers to accurate communication and reporting from defensible information sources. It also requires sound evaluation design, systematic data collection and information management, with methodical analyses, explicit reasoning, and justified conclusions (Yarbrough et al., 2011). Linking to the second assumption underpinning this book that expects rigorous evaluation, previously discussed in regards to feasibility, informal everyday evaluation in the case study non-profits suffers from issues with these expectations while, on the surface, formal evaluation appears to meet them. Document review in Chapter 5 showed that the design of formal evaluation in the case study non-profits is logical, data are organised and thoughtfully presented, and recommendations are justified. However, as discussed in Chapter 6, these evaluations are largely unused and practitioners raise concerns as to their accuracy, in addition to other complaints. On the other hand, informal everyday evaluation is sporadic, sometimes haphazard, data collection is often unsystematic and disorganised, yet practitioners trust and use these findings. Practitioners comment that these findings are trusted because they are gathered directly from non-profit practitioners and community recipients by staff and the findings resonate with primary intended users’ knowledge and expectations of the program. When findings ring true and have been arrived at through a process of mutually engaged co-inquiry, information can be trusted, whether the results are positive or negative. This suggests minimising the distance between information sources and users for increased accuracy and trustworthiness.

While hard scientific data is often considered accurate, practitioners suggest otherwise; highlighting complexity, relationships, and positionality as vitally affecting evaluators’ ability to accurately hear, gather, and interpret knowledge. Practitioners are suspicious as to whether external evaluations are able to accurately portray or understand their programs and recipients. As the director of a rural African non-profit mentioned in Chapter 6, ‘you can make a report say anything…Numbers can be twisted. Words are just words on a paper’. This sentiment reduces practitioner trust in the opinions and interpretations of outsiders, lending greater feasibility to internal and informal everyday evaluations. Practitioners suggest numerous reasons for this including unmatched values, short fieldwork times, and failure to build sufficient rapport to elicit accurate responses from community recipients. Practitioners highlight outliers they consider accurate in Chapter 6, pinpointing the reasons for their trust are due to long-term relationships between the external evaluator and the organisation, matched values, or simply that the evaluations regurgitated the words of non-profit staff.

Practitioners, including one who works as an external evaluator in a suburban Australian non-profit, comment that community recipients are more likely to be open and honest with staff they know and trust, an idea that splits opinion in the evaluation literature (Conley-Tyler, 2005). Further, internal staff have deep knowledge of context and organisational values that external evaluators are unlikely to have time to cultivate, unless they engage in a long-term relationship with an organisation, which may jeopardise their perceived or actual objectivity. Despite debates on objectivity discussed in Chapter 7, the findings suggest that internal staff or long-term external evaluators are well placed to conduct evaluation with accuracy due to good contextual understanding and rapport enabling open and honest discussion.

While this analysis of accuracy has focused on intangible aspects of assuring accuracy, tangible aspects are noticeably variable in the case study non-profits. During my observations, I witnessed a range of different data storage and organisation approaches. While some practitioners were quickly able to locate survey results or whatever other documentation they were seeking to show me, others were unable to find the sought documentation under piles of paper and disorganised computer systems, as raised in Chapter 5. Although there was no mention of data management impacting accuracy of evaluative conclusions, this could be a consideration when developing rigorous internal and informal systems.

Revising Evaluation for Small Non-Profits

The research undertaken for this book discovered that formal evaluation in small development non-profits is underutilised and often in breach of community development and evaluation standards, being largely resource-intensive, top down, and not useful. Outliers are formal evaluations conducted by internal or external evaluators who focus on primary intended user (staff) needs, collaboration, and skill sharing. Informal evaluative processes are highlighted as utilised and aligning more closely with community development and evaluation standards than the bulk of formal evaluation, being largely embedded, bottom up, and meaningful. These findings suggest that most formal evaluation has little point other than upward accountability while informal everyday evaluation checks effectiveness and improves processes and programs. However, observations corroborated by practitioner comments suggest that non-profits’ stated desires for downward accountability and community recipient inclusion in evaluation are limited.

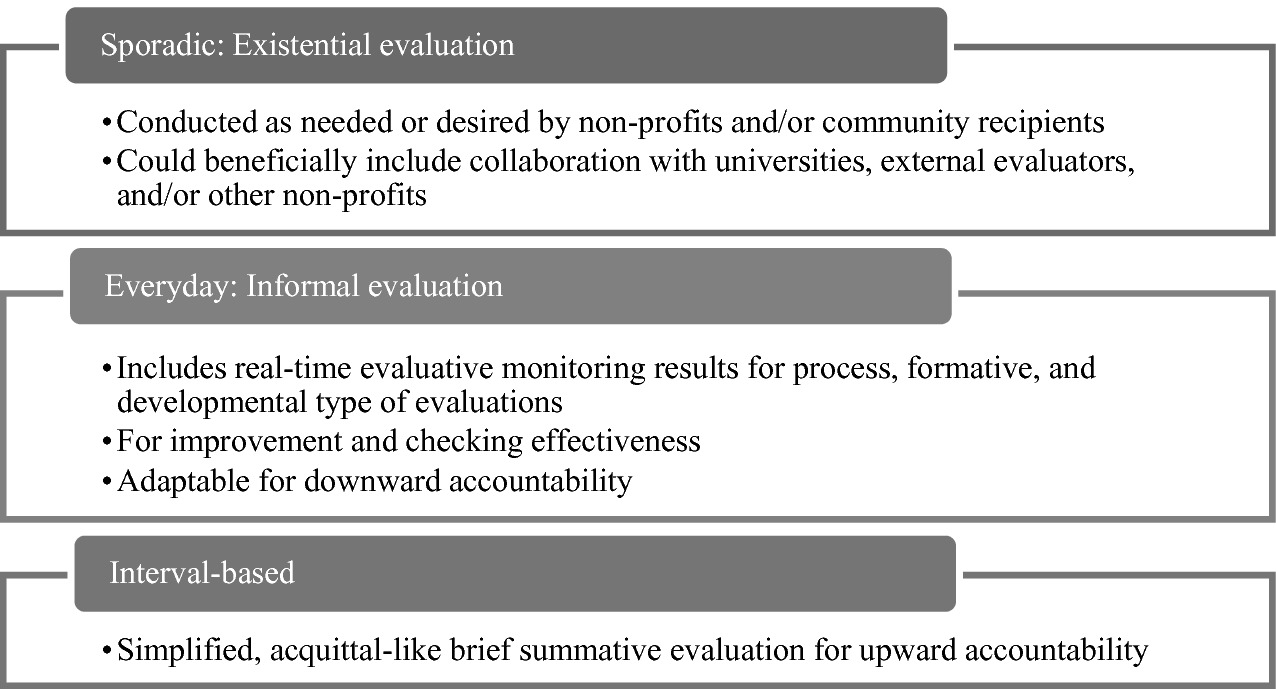

Building on these findings, Chapter 7 presented practitioner ideas for improving evaluation in small development non-profits. This section groups these ideas together into a three-pronged model for context-sensitive evaluation, focusing on deep evaluative research, rigorous informal evaluation, and simplified upward accountability. While designated as a ‘model’, in reality it is a collection of practitioner-led ideas intended to inspire small non-profits and provide a starting place to adapt their own alternatives. The model seeks to address barriers to evaluation in small non-profits and utilise their strengths while heeding community development and program evaluation standards. The model is underpinned by utilisation-focused principles, with users and evaluators (whoever they may be) encouraged to outline clear and realistic purposes and intended uses for their evaluations, and hold responsibility for utilisation, a point emphasised by fourteen per cent of practitioners and raised in the evaluation literature (Patton, 1988, 2012). The ideas within the model are eclectic, for use with a range of existing approaches such as empowerment evaluation, appreciative inquiry, or action research. As the model provides a high-level framework drawn from the ideas of fifty practitioners in small non-profits, it is highly adaptable to allow for contextual sensitivity. To develop the model for use in organisations, the community development and evaluation standards provide useful prompts to critically implement evaluative activities with fidelity to values and rigour.

Program evaluation and what lies beneath

An existential evaluation could interrogate non-profits’ motives, assumptions, and worldviews to ascertain their potential for negative and positive short- and long-term impacts on the people and communities with whom they work. The notion of existential evaluation could enhance critical thinking and clarify strategic direction—actions practitioners identify as requiring attention in Chapter 7. For example, the rural South Asian non-profits’ desire to examine the impact of girls’ empowerment on their community, raised in Chapter 7, involves a deep piece of research that asks stakeholders to critically evaluate the premise of the organisation and its objectives, which centre on girls’ empowerment. Additionally, existential evaluation could incorporate the collaborations with universities, other non-profits, and external evaluators raised as potentially useful by practitioners in Chapter 7, to assist them with organisationally-identified needs such as research expertise, funding acquisition for research, formal ethics approval, or dissemination. Inclusion of these external actors could also serve to question and prompt non-profit practitioners to avoid echo chambers, self-fulfilling prophecies, and confirmation biases.

Throughout this research, practitioners comment that they place significant value on community recipients and downward accountability. At the same time, nearly a fifth of practitioners comment that they would like to enact this value more strongly and authentically, identifying top-down evaluation and tokenistic participation as problematic. Conducting an existential evaluation project could be an opportunity to address this through community-led research using approaches such as participatory action research or Indigenous research methods. This notion aligns specifically with the third community development standard on participatory planning that recommends supporting recipients to undertake and use their own research. Further, embarking on community-led research could help organisations better understand the priorities, values, and felt concerns of their target group.

Build Rigour into Informal Evaluative Processes

The second part of the practitioner-led ideas for evaluation improvement centre on building rigour into informal everyday evaluative processes, as raised in Chapter 7. Systematically scheduling and capturing the data from these processes, shown to be highly utilised in Chapter 6, could log change, monitor effectiveness, and facilitate accountability in a bottom-up manner that aligns with community development and evaluation standards. Ebrahim (2005, p. 79) highlights that these ‘simple and flexible systems’ are more relevant and feasible than ‘elaborate or highly technical systems’. As shown in Chapter 5, these pre-existing processes are already embedded in practice in and are part of program delivery; therefore, they are not an additional burden on resources. Strengthening this approach aligns with Wildavsky’s (1972, p. 509) notion of the ‘ideal organization’ as one that self-evaluates, ‘continuously monitoring its own activities so as to determine whether it [is] meeting its goals or even whether these goals should continue to prevail’.

Practitioners identify that mainstreaming evaluation into embedded informal processes requires critical thought and space for open dialogue, aspects of inquiry that practitioners highlighted a desire and need to cultivate in Chapter 7. Using the community development and evaluation standards to think about and build rigour into these everyday processes could help small non-profits deconstruct and reconstruct their ways of doing and thinking. Practitioners seek debate and well-thought-out ideas where decision-making processes are ‘made explicit, opened up to examination, and contested’ to provide strong rationale for their choice (Cheek, 2007, p. 106). Further, these deliberative inquiry processes could help small non-profits and their stakeholders come to consensus over definitions of key terms and concepts, fostering mutual understandings to reduce ambiguity and confusion.

There is potential that building rigour into these informal processes could result in another resource-intensive trap, with hordes of meeting minutes, meticulously collated statistics, and other sources of data gathering in numerous unsorted and disorganised piles. Avoiding this trap could link with the need, identified by practitioners in Chapter 7, for better databases and technology with reporting capabilities to reduce administrative burden. Further, small non-profits could benefit from support to devise these data management systems, a use corroborated by practitioners in Chapter 7 who identify that external evaluators could help them develop effective and context-sensitive evaluation systems and frameworks. Integrating principles from developmental evaluation could be particularly suited to this form of working as it focuses on continuous improvement without necessarily requiring formal written reports (Patton, 1994, 2011). Despite finding a general lack of utility around reports in this research, there may be value in the exercise of writing working documents on an ‘as needed’ basis to provide a tangible artefact to refer to in deliberations.

Noted during my observations, small non-profits have started to develop ways of recording everyday data in useable forms. One example is an Excel document where practitioners designate a row for each new meeting and list key ideas and decisions in succinct statements. Together these statements demonstrate a timeline of organisational change and highlight movement and development in thought and action. Collating themes from these points at intervals could provide a rigorous and detailed view of improvement, challenges, and effectiveness. Practitioners note many other documents, such as case notes, action plans, supervision plans, and worker journals, that they feel hold valuable information that could be tapped for evaluation.

It’s just an anecdote when told in isolation and heard by amateurs. But I’m a professional anecdote collector. If you know how to listen, systematically collect, and rigorously analyze anecdotes, the patterns revealed are windows into what’s going on in the world. It’s true that to the untrained ear, an anecdote is just a casual story, perhaps amusing, perhaps not. But to the professionally trained and attuned ear, an anecdote is scientific data – a note in a symphony of human experience. Of course, you have to know how to listen.

Patton’s role as a professional anecdote collector bears similarity to an evaluation consultant’s identification of evaluators as custodians of people’s stories in Chapter 7. As presented in Chapter 5, the work practitioners are already doing, listening to people’s stories and collecting case studies to display on their websites, could be informed and guided by methods such as Most Significant Change (Davies & Dart, 2005).

Lastly, as presented in Chapter 7, practitioners specifically raise that they wish to question, reassess, and renew the ways in which their evaluative processes support empowerment and agency of the people and communities with whom they work. While small non-profits try, and many of the case study organisations are involving community recipients in their work in significant ways, practitioners argue that non-profits should always seek do better, agreeing that recipients’ capabilities are regularly overlooked and their ability to add value to evaluative assessments often go unrealised. Practitioners’ comments align with Chambers (2009, p. 246) who emphatically states that, ‘it is those who live in poverty, those who are vulnerable, those who are marginalised, who are the best judges and the prime authorities on their lives and livelihood and how they have been affected…We need to make more and better use of them. Again and again, the injunction bears repeating: ask them!’ Bottom-up development of informal everyday evaluation offers a unique opportunity to include community recipients and trial the numerous participatory evaluation approaches, some of which are mentioned in Chapter 2, to enhance recipients’ power and control over non-profit processes. Currently, as reported in Chapter 5, small non-profits’ time is consumed with doing top-down evaluation for donor appeasement, renegotiating this situation could provide non-profits and community recipients with a chance to re-do evaluation in a form that inverts this traditional relationship. In this, recipients and practitioners become the creators of evaluative processes while those traditionally on the top act in supportive, ancillary roles.

Developing informal everyday evaluation as a bottom-up approach to evaluation links with community development values and begins to address the marginalisation and disempowerment of small non-profits discussed in Chapter 4. While not speaking directly about evaluation, Kenny’s (2011) argument that subordinate groups (such as small non-profits) can and should seek to negotiate, redefine, and transform the ideas and practices of the orthodoxy supports these organisations forging a new path. This transformation is central to empowerment as, in the ‘processes of reconstruction, subordinate groups can define new values and meanings, and identify other options and new ways of doing things. New ways of looking at things open the way to resisting the dominant groups’ definition of what is proper and reasonable’ (Kenny, 2011, p. 183). This provides an opportunity for community recipients and small non-profits to seek joint emancipation.

The final part of the three-pronged practitioner-led solutions for effective evaluation in small non-profits is for these organisations and their donors to negotiate simplified mechanisms for upward accountability. The findings reported in this book point to a clear dichotomy in evaluation practice, noted in the evaluation literature as a split between evaluation that is accountable upward to donors and evaluation that is accountable downward to community recipients (Chouinard, 2013; Ebrahim, 2003; Kilby, 2006). Patton (2012) identifies this split noting that summative evaluations are most useful for the top echelons of evaluation stakeholders, the donors and board, while the utility of summative evaluation for practitioners involved in program improvement is reduced. Formative and developmental evaluations can be less useful to executives who want accountability information but can be of high utility to non-profit staff and community recipients who are interested in forming and reshaping programs to improve and develop them (Patton, 2011, 2012). While this dichotomy is documented in the evaluation literature, the impact of this finding on practice is minimal. There are expectations that evaluation should be everything to everyone, although in practice, including in the case study non-profits, this rarely occurs as downward accountability is pushed to the sidelines and undermined by obligations to upward accountability (Jacobs & Wilford, 2010). Further, the expectation that evaluation should be shared with donors (as demonstrated in Chapter 7) stifles non-profits’ desire and ability to engage in deep critical inquiry due to the threat of sanction (Donaldson, Gooler, & Scriven, 2002; Ebrahim, 2005; McCoy et al., 2013). This can particularly affect small non-profits with limited funding streams resulting in resource dependency and conditions of high upward accountability (Ebrahim, 2005). Recognising that organisations, community recipients, and donors require different types of evaluation may help reduce confusion and resource-wastage on lengthy evaluation reports that are of limited utility to each stakeholder group.

In Chapter 7, practitioners suggest that it would be helpful if they had a simple template or acquittal form to fulfil their upward accountability needs. This would allow donors to find out precisely what they want to know and minimise the time and effort small non-profits are currently spending trying to appease donors with detailed reports that they suspect are unused and even unread, as raised in Chapters 7 and 8. Donors could develop this template, or co-design it with other stakeholders, with an emphasis on keeping it short and including only questions backed by rationale for use. A specific and simple evaluation for upward accountability could clearly focus on the ‘proving’ element of evaluation and include key findings from existential and informal evaluations to demonstrate effectiveness and highlight challenges and change. Additionally, these evaluations could be a suitable area to utilise aggregated and reductionist forms of measurement heralded by the evaluation orthodoxy, as balancing the various approaches to evaluation helps triangulate and strengthen data collected through more interpretivist forms of evaluation. Separating and simplifying upward accountability could reduce gamesmanship and administrative burden while providing small development non-profits with opportunities to implement critical approaches such as existential evaluation and rigorous informal evaluation. This could promote a recipient-centred evaluative shift towards evaluation as a tool for critical inquiry and improvement, rather than a tool for compliance.

A model for evaluation in small development non-profits

As argued previously, this model is highly adaptable and could inspire other ideas or be implemented in part or full depending on non-profit circumstances and donor requirements. In a best-case scenario, if a donor was satisfied to receive updates from context-sensitive informal evaluations, a negotiation that may be a ‘tough sell’ (Green, 2016, p. 238), this could negate the need even for simplified interval-based evaluations. This could transform evaluation to a place where it is ‘no longer discrete activities, but part of a longer learning process’ (Shutt & McGee, 2013, p. 8). Indeed, the findings of this book suggest that ceasing formal interval-based evaluation altogether may have minimal negative effect on small non-profits, although it could free-up organisational resources, particularly time and funds for reinvestment into existential evaluative research and informal evaluation.

Implications and Conclusions

The implications of this research are significant for small development non-profits as this book highlights previously unrecorded practices of how these organisations do and use evaluation. The findings show that they are conducting and utilising evaluation, but not always in expected ways. The findings suggest that formal interval-based evaluation, as currently practised, is generally not worthwhile for these organisations, despite often painstaking and rigorous reporting. Primary intended users rarely use evaluation reports and when they do, evaluation mainly motivates small non-profits to implement improvements of which they were already aware needed attention. The findings suggest that formal evaluations are often unworkable; they suffer from concerns surrounding accuracy, face issues with feasibility, propriety, and ethics, and are not answerable to themselves through meta-evaluation. Additionally, there is little demonstration within the findings that formal evaluation seeks to align with community development. Rather than being used as a part of the community development process where evaluation could enhance community recipient empowerment, enact social change, and strengthen sustainability potential, formalised evaluation is often an added burden. Conversely, the case study non-profits demonstrate community development aligned informal evaluation procedures for identifying improvements, checking effectiveness, and maintaining accountability; processes practitioners did not initially identify as evaluative.

The findings of this book have informed construction of a non-profit-led model for improvement, effectiveness, and accountability in these organisations, building on practices practitioners identify as pragmatic. However, without conscious effort to align these efforts with the community development and evaluation standards, and maintain a focus on utilisation, this new model could simply revert to forms of evaluation the findings highlight as largely pointless. This demonstrates the importance of the fifth evaluation standard, evaluation accountability, which emphasises the need to conduct meta-evaluations through regular critique and review of approaches (Yarbrough et al., 2011). Rather than conducting evaluation for evaluation’s sake, evaluation requires continual assessing: Is it useful and used? Does it have a purpose? Is it meaningful to us and other stakeholders? Using an approach such as appreciative inquiry and prompts from the community development and evaluation standards, small non-profits could build on their evaluative strengths and discard elements of practice that undermine their values, or that are not useful, feasible, ethical, or accurate. This supports the notion of simplifying evaluation promoted in the non-profit literature (Ebrahim, 2005; Kelly, David, & Roche, 2008).

These findings highlight a greater concern in the evaluation and development disciplines, acceptance of the axiomatic ‘good’ of program evaluation. As discussed throughout this book, the extant literature identifies disconnects between community development praxis and the evaluation orthodoxy (Doherty, Eccleston, Hansen, & Natalier, 2015; Ife, 2013; Lane, 2013), necessitating context-sensitive approaches. However, despite alternatives, non-profits, such as the case study organisations that participated in the research for this book, continue to implement the tools and approaches of the orthodoxy due to top-down pressures and inculcated ideology surrounding the hierarchy of evidence (Chouinard, 2013; Eyben, Guijt, Roche, & Shutt, 2015; Lennie & Tacchi, 2013). This suggests that the commonly accepted idea of methodological appropriateness as the platinum standard (Patton, 2015), is accepted in rhetoric more than in practice.

While recognition of the value and potential of informal everyday evaluation in small development non-profits is this book’s key contribution to practice, noting the evaluation disciplines’ resistance to deep self-critique is its key contribution to theory. Finding that formalised evaluation continues to suffer from issues of underutilisation, even in small non-profits, reinforces the need for deconstruction and ‘radical rethinking’ of the evaluation discipline (Shutt & McGee, 2013, p. 8).

As discussed in Chapter 3, scholars in the development discipline, notably those from post-development and critical development schools of thought (and their critics), have deconstructed development assumptions and ideologies to assess their worth and impact. These critiques continue to strengthen, sophisticate, and reconstruct the development discipline and its alternatives, imbuing practitioners with healthy scepticism and uncomfortable feelings of uncertainty. Further, development practitioners have access to literature, think tanks, and other resources that recognise and unpack our feelings of unease, often leaving us feeling more sceptical and uncomfortable, but thinking nonetheless.

The evaluation discipline has dipped a trepid toe in these heretical waters in the many discussions on evaluation underutilisation. However, negative findings are quickly allayed and surface-skimming solutions cast. This book proposes the need for a new school of evaluative thought in the footsteps of post-development and critical development studies. A place for radical evaluation studies where evaluators can grapple with their greatest concerns and rethink evaluation to develop ways of improving programs, checking effectiveness, and maintaining upward and downward accountability that are truly useful, purposeful, and meaningful.