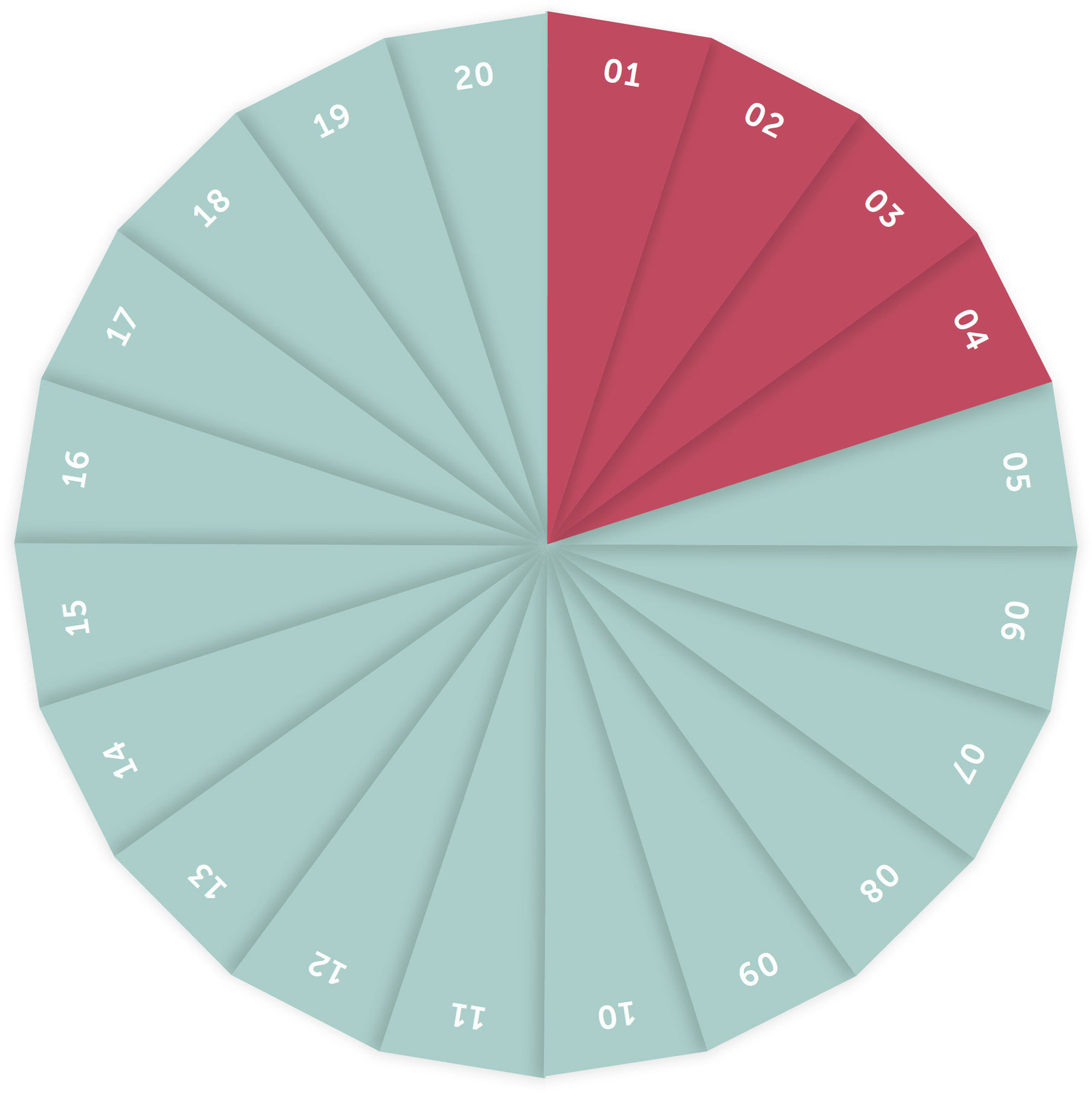

SECTIONS

01 BEING ME

The idea of a rational subject is socially constructed.

02 GROUP CHAT

Groups and individuals perform actions in different ways.

03 FREE THINKING

Are our political views wholly determined by our upbringing?

04 HARD FACTS

The line between ‘true’ and ‘false’ isn’t always easy to find.

‘We can disagree and still love each other, unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist.’

James Baldwin

What kinds of things get into arguments? Argumentative things, sure – but more broadly? Things like us. Humans. People. Individuals. In this chapter, we’re going to focus on ‘metaphysics’ – the area of philosophy that examines the nature of reality. We’re going to investigate the metaphysical character of these special entities who get into fights, converse, engage in dialogue and debate. We’re going to look at their nature, and how they exist in the world.

For thousands of years, philosophers have been putting forward stories about the kinds of beings we are. Whether they construe us as essentially ‘thinking things’ or ‘embodied consciousnesses’, every story moderates the ways in which we interact with each other. One account, popular since the seventeenth century, holds that we are ‘rational subjects’ – boundaried, self-governing intelligences who are privy to our own thoughts and nobody else’s. In section 1, ‘Being Me’, we’re going to examine this seemingly intuitive notion. Are our thoughts really so discrete? There are certainly some situations – like the co-authored text you’re currently reading – which suggest that the reality is more complex.

We’re also going to look at the larger entities – groups, communities, societies in general – that these human individuals make up. In section 2, ‘Group Chat’, we’re going to think about ‘group agency’ and what it means for a group to have a ‘will’. How does social power move through individuals? Can the ‘will’ of a society shape the actions of its citizens?

In the third section, ‘Free Thinking’, we’re going to look at agency more generally. When we engage in dialogue, we typically do so on the understanding that each of us has the power to change minds – our own and other people’s. This understanding rests on metaphysical assumptions about ‘free will’. How realistic is it to think we can transcend the effects of our backgrounds? Is it impossible for us to escape the causal chains that precede us?

The final section, ‘Hard Facts’, deals with a philosophical concept that’s frequently and often problematically invoked in daily discourse: truth. Arguments are normally arbitrated by reference to what’s ‘true’ or ‘false’, ‘fact’ or ‘fiction’, ‘objective’ or ‘subjective’, and these ideas are all connected to specific conceptions of reality. Are there really external facts, which we can point to in order to decide who’s right or wrong, or is everything just relative?

This chapter attempts to show that our appeals to facts, or our ideas about free will, are grounded in long-running metaphysical debates. Whenever you say something’s ‘true’, or argue for the ‘freedom to choose’, you’re assuming something about the structure of the world, about the way reality actually, genuinely is. The aim here is to bring these assumptions to light to see how they affect the ways we engage with one another.

BEING ME

‘If I were you …’

‘But you’re not! You don’t get it! You don’t know what it’s like!’

Words are wonderful, but at the end of the day they only go so far. There are some thoughts, feelings and lived experiences that are almost, if not actually, impossible to communicate. In the exchange above, we see how this features in our everyday disagreements.

At the heart of such claims is the thought that I am distinct from you, and that there are certain things, desires and opinions that exist in the privacy of my head and are inaccessible to you.

This idea, that we are discrete ‘rational subjects’, cordoned off from the world, transfuses our daily lives and our politics. For instance, it underpins our democratic voting procedures: every member of society has their personal view (about who should be elected) and communicates it with a cross in a box or the raising of an arm. It’s the idea of a rational subject that makes sense of opinion polls and surveys, which ask what people think (because only they themselves know). It’s this notion that causes us to bristle when others claim to have greater insight into our views than we do ourselves. We might say: ‘No one knows me better than I know myself.’

This seems a perfectly ordinary, almost natural way of looking at the world. But while there may well be features of human experience that inform the idea of a ‘rational subject’ (like our experience of the privacy of our personal thoughts), the American philosopher Amélie Oksenberg Rorty points out that human experience has historically been theorized in different ways. The rational subject is just one of these ways and a product of a particular socio-political context.

The idea of a discrete, closed-off, thinking thing emerged during the period known as the Western Enlightenment or (in a similarly self-congratulatory vein) The Age of Reason. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, philosophers like René Descartes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau contributed to what is now a hugely influential picture of personhood. They introduced the idea of the boundaried nature of our selves, along with our capacity for reason. So we find in Descartes’ Meditations (1641) the idea of a rational subject so far removed from others it can come to doubt its very existence. In his famous argument, ‘Cogito ergo sum’ (‘I think therefore I am’), Descartes posits the existence of a thinking being who can only really be sure of its own existence. It knows itself, but not others.

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant also contributes to this train of thought. In Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Kant argues that reason is a special capacity, possessed by each individual, which allows us to arbitrate the truth of judgements – and thereby reach decisions for ourselves. Reason allows us to ‘self-govern’, or act ‘autonomously’.

The rational subject is not a natural concept. Nor is it a metaphysical whimsy. It emerged in response to institutional abuses by ruling powers of the time, like the Church and the monarchy. The rational subject is understood by Kant to have ownership of its own thoughts, to possess opinions, and to be able to appeal to reason just as well as any king or bishop.

NO ‘I’ IN TEAM

The rational subject gained so much theoretical traction during the Age of Reason that it was reified – made real – and figures prominently in metaphysical systems of the time (the philosophical accounts of the structure of reality). Modern thinkers like Kant and Descartes held that along with material things (like particles) and qualities (like colours), there are these thinking things too – selves, or persons.

However, in becoming a more substantial entity, the politics of the rational subject was unhelpfully obscured. That, at least, is the contention of the Critical Theorists. Based in Frankfurt, and known not-so-imaginatively as the Frankfurt School, twentieth-century thinkers like Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer and Herbert Marcuse critique the seemingly common-sensical notion of a discrete thinking thing.

Marcuse, for example, sees the rational subject as an essential part of the economic system known as capitalism (in which private owners employ others in order to make profit in the marketplace). In One-Dimensional Man (1964), he argues that the notion of a distinct, self-governing individual – a manageable body, who can labour and perform discrete tasks – is a socioeconomic necessity of market capitalism. Here, rational subjects are the building blocks out of which a capitalist economy is constructed.

Postmodern and feminist scholars have revealed other hidden – and troubling – features of the rational subject. This idea of subjecthood is grounded in a specific notion of reason, which appears to be constructed to disenfranchise certain groups of people. One of the ‘great luminaries’ of the Enlightenment, Kant promoted a conception of reason that was indelibly bound up with his profound racism. In ‘The Color of Reason’ (1997), Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze examines texts such as Kant’s ‘On the Different Races of Man’ (1775), in which Kant positions white Europeans at the top of a racial hierarchy. Eze points out that the notion of the ‘universal human subject’ is, for Kant, a white European man. Similarly, feminist scholars like Genevieve Lloyd and Rae Langton have drawn attention to the way Kant’s ‘reason’ is bound up with his corrosive sexism. His approach to ‘intellectual women’ was horrendously dismissive – saying they ‘might as well even have a beard’. As formulated by Kant and his Enlightenment friends, reason is implicitly ‘gendered’. It’s understood to be masculine – a capacity possessed by men (with beards).

It’s important, therefore, to recognize the context from which our self-conception emerges. While ideally the ‘rational subject’ is a position that’s democratically open to all – bishop and peasant alike – in reality it carries with it assumptions about gender, race and class (among others).

‘Reason’ has a history. Whether we like it or not, this history can inform our ideas about who is and isn’t a rational subject. It bubbles to the surface when, for instance, women are accused of being emotional, hysterical or irrational. And it can shape how we perceive our conversation partner and how we respond to them.

GROUP CHAT

In 2016, the British public was asked to vote on whether or not to leave the European Union. The result – 48.1 per cent of voters backed ‘remain’; 51.9 per cent backed ‘leave’ – came to be known as ‘Brexit’, the British Exit from the EU. After the referendum, Prime Minister Theresa May – who was charged with upholding the result – said repeatedly that she was enacting ‘the will of the people’. This phrase made many uncomfortable, especially those whose desires were not reflected in the outcome. This is a discomfort we sometimes feel when it comes to the phenomenon known as ‘group agency’.

Individual agency seems pretty straightforward. Individuals have control over their own actions and unless coerced or otherwise constrained, they can do whatever they choose to do. Occasionally, however, individual agents come together, and through a process of joint deliberation they can enact things together – like leaving a union of nation states. The group acts as an individual agent. As the Brexit vote demonstrates, however, such group actions can be highly confusing. If a people has a ‘will’, where is it located? What kind of force is it?

The idea of ‘a general will’ is found in canonical form in the work of the eighteenth-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In his book, The Social Contract (1762), Rousseau distinguishes between ‘particular will’, which focuses on the interests of an individual (your desire for an ice-cream), and ‘general will’, which focuses on communal interests (the public ‘desire’ for something like a National Health Service). For Rousseau, ‘As long as several men assembled together consider themselves as a single body, they have only one will which is directed towards their common preservation and general well-being.’ This general will is manifest in the result of a vote.

It’s a popular and influential thought, but not without its critics. Among them is the French political activist Benjamin Constant who, in his Principles of Politics (1815), asserts that the idea of a general will leads towards despotism (the exercise of absolute power by a state leader or ‘despot’). Constant focuses on Rousseau’s notion that, once established via the democratic process, the general will becomes unimpeachable. The members of the group have to submit to it completely, to the point where those who voted against it must admit to having been in error.

Constant saw this political model as open to grave misuse by those in power. What if the means by which the group determines the general will is dodgy? What if the self-appointed ‘representatives of the people’ are dodgy too? According to Constant, Rousseau’s theory leads us to surrender ourselves ‘to those who act in the name of all’. Politicians who put themselves forward as ‘the voice of the people’ might, in reality, be anything but.

‘WHAT’S THE RATIONALE?’

Making group decisions is difficult, clearly. ‘You can’t please everyone’ is almost a truism when public opinion about policy is so dramatically divided. And it’s a difficulty that occurs at every level – international, national and local. Whether it’s in a polity or a business, a multinational company or a freelance partnership, people disagree.

There are methods, however, for making group deliberation easier and more effective. In his Theory of Justice (1971), the political theorist John Rawls emphasizes the importance of recognizing different forms of ‘practical reasoning’. What, he asks, is the framework within which our group deliberation takes place? Or put another way, how should we engage in the democratic process? Settling such questions allows us to deliberate together more carefully.

PLURALISTS

For ‘pluralists’, democracy (from the Greek demos, ‘people’, and -cracy, ‘rule’) is a matter of group members basing their decisions on private interests. There is a plurality of individual concerns and everyone votes with their own particular issues in mind. This can involve teaming up with people who share the same interests – but it needn’t. For the pluralists, there’s no call for group members to engage with each other except insofar as they might further their own individual interests.

This is a mercenary approach to group deliberation. It neglects something we call ‘the common good’.

COMMON GOOD

The common good can be understood as encompassing communal interests (an educated public, say, or a pleasant work environment) and facilities (state-owned libraries or, on a smaller level, an office biscuit tin). Political philosophers from Aristotle onwards have argued that the common good should be the primary focus of deliberative democracy. When we vote as a group, we should vote with everyone’s interests in mind, not just our own. Not doing so is seen to be a weakness of the pluralists’ position.

IF THE PEOPLE HAVE A ‘WILL’, WHERE IS IT LOCATED?

FREE THINKING

Imagine you’re chatting with your granddad and he says something transphobic. Later on, your mum excuses him, saying, ‘He’s a product of his time’. She might even say, ‘He can’t help it, it’s how he was brought up’.

In saying this, your mum is invoking the metaphysical thesis known as ‘determinism’. Occasionally called ‘causal determinism’, it holds that all events are completely and utterly fixed – or determined – by earlier events. It’s an intuitive position. We know the world works according to specific physical laws and that things are causally connected and result from prior events. So we can assume that, with sufficient information, we could (theoretically) work out what the effect of all our actions would be. This would include people’s behaviour. Granddad’s transphobia may be the direct and inevitable consequence of his growing up in a transphobic society, just as your fear of dogs may be an inevitable consequence of your having been bitten by a dog when you were little. It makes sense. Cause. Effect.

Of course, with our limited understanding of the world, we may never be able to actually predict the future. But it’s possible, in principle, and that’s all your mum needs in order to absolve your granddad. It’s not his fault, he’s just a product of his time.

There are other ways of putting distance between ourselves and our actions. We often talk about being caught up in the ‘zeitgeist’ or the ‘spirit of an age’. These phrases are borne from the philosophical tradition known as ‘Historicism’, popular among German philosophers in the eighteenth century. Historicism holds that our actions are expressions of a cosmic will. The German thinker Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel believes that individual actions are manifestations of this ‘world soul’, or universal ‘spirit’ (geist).

Weird, right? Most of the time we tend to think we’re in charge of our destinies rather than puppets of some omniscient deity, or geist, or outputs of the plodding mechanics of the physical universe. This type of deterministic thinking is at odds with how we engage with each other in arguments and conversations. We think we can persuade people – and be persuaded – with arguments (and perhaps a sprinkling of rhetoric). We think we can reach into a seemingly deterministic world and exert control over ourselves and others.

Are we deluded? Have a think. When was the last time you changed your mind during a conversation – or someone else changed their opinion because of something you said? How many of your beliefs have you managed to actively reassess and relinquish since they were formed in your childhood?

‘THINK FOR YOURSELF’

Are our characters set in stone from the moment of birth? Working at the start of the nineteenth century, ‘Romantics’ like Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling thought our understanding of ourselves was the result of a process of self-discovery. Through self-investigation, introspection and exposure to certain meaningful encounters (awe-inspiring things like seascapes and mountain ranges), we find ourselves. There is, Schelling thought, some true essence that makes you you. You may be a hero or a coward, a villain or a saint – whatever it is, there’s some inner-core baked into you, waiting to be discovered.

This idea nicely complements the deterministic worldview – but it’s not quite as fatalistic as some forms of ‘hard determinism’. Life for the Romantics doesn’t just unfold joylessly according to a cosmic blueprint. The Romantic is a ‘compatibilist’, who holds that determinism is compatible with a degree of freedom. Sure, they say, the self might be there already, fixed by nature, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have a role to play. It’s up to us to find out what we are. And it’s up to us to act according to, and to cultivate, our true nature. We can be free, they say, in the way a river may be free to run its course, or a balloon, once released, is free to soar up up up.

In contrast to the Romantics,‘Existentialists’ – like Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre and Frantz Fanon – thought compatibilism was an impoverished form of freedom. Working in the twentieth century, these thinkers focused less on self-discovery and more on self-creation. Their mantra was ‘Existence precedes essence’. You come into existence then decide how to exist. You decide what to exist as, who to be. In its most radical form, existentialism holds that you are utterly unconstrained by your upbringing. You can break free, completely, from the causal chains that brought you into the world.

If these positions – the Romantic and Existentialist – strike you as too extreme, you’ll be relieved to learn there are philosophers who tread the line between the two. The philosopher and cultural theorist Kwame Anthony Appiah is one. He recognizes the importance of acknowledging the circumstances you’re born into, the capacities you enjoy and the privations you suffer, but he also denies that we have to be determined by these facts. In defining ourselves, he says we engage in creative acts of self-construction: ‘To create a life is to create a life out of the materials that history has given you.’

Seyla Benhabib, a professor of philosophy at Yale, toes a similar line. We are not merely extensions of causal chains, she says. We ‘are in the position of author and character at once’. Our identity is not just a matter of pre-made artefact nor of spontaneous generation. It’s a creative combination of the two.

HARD FACTS

Imagine a world where everyone lies. You ask someone the time and they tell you it’s noon when it’s midnight. You ask for directions and you’re told to go left instead of right. What kind of world would this be? A highly dysfunctional one. When we talk to each other, we rely on our partners telling the truth.

But what is truth, exactly? One widespread view states that claims about truth and falsity rely on the assumption that there’s a real, external world that exists independently of how we conceive it. Statements that grass is green, or water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen molecules, are true – they’re facts – if they accurately map these features of the external world.

For the ‘realist’, the world can meet our expectations or it can frustrate them. It does so irrespective of what we think about it. The molecular composition of water is not a matter of opinion (it’s not ‘subjective’); reality has the final say (it’s ‘objective’).

Of course, there are different kinds of facts, and different domains where ‘truth’ and ‘falsity’ appear to apply. Some are more contentious than others. Scientific facts seem relatively straightforward. Through empirical investigation (via your senses) you can work out, for instance, that humans need water to survive. That’s a fact that’s hard to dispute without risking dehydration. But what about facts in other spheres? Is there a fact of the matter about whether an artwork is beautiful? The ‘Mona Lisa’ isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. And what about morality? Are there moral facts floating about in the external world? Do you think, as ‘moral realists’ like Plato did, that we can discover objective moral truths – like the fact that the killing of innocents is always wrong – in the same way that we can discover facts about the molecular composition of water?

The concepts of truth, objectivity and fact can be confusing. ‘Postmodernists’ like Judith Butler and Bruno Latour have shown that they can also be politically fraught. They critique what they see to be the idea of Universal Truth that emerged during ‘Modernism’ (the European intellectual milieu of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries), and show how the idea of objectivity has been historically used as a tool of oppression. Social bodies like the state or the scientific establishment can declare that they have neutral access to what is really the case – when in fact they don’t. ‘Facts’, say the postmodernists, ‘are not discovered, but made’; created by certain people in order to control others. The racist views that underpinned the transatlantic slave trade were couched as objective fact, just as homosexuality was medically pathologized in the early twentieth century.

Given the way claims to objectivity and truth can be abused, perhaps it’s best to just declare that ‘Everything’s relative!’ ‘It’s all just a matter of opinion!’ This appears to be the direction that the postmodernists are leading us in. But this approach has its problems too.

‘THE POST-TRUTH ERA’

If you’re not a realist, you may be a relativist. For the relativist, things like truth, goodness and beauty are relative to some frame of reference – and there are no absolute standards with which to judge between these competing frames. For instance, an act that’s considered polite in one culture (collecting mucus in a small towel known as a ‘handkerchief’) may be seen as distasteful in another. Or something that’s deemed morally acceptable in some countries (eating the flesh of dead animals) may be deemed intolerable in others. The boiling point of water is normally taken to be 100 degrees Celsius, but in certain situations (when dissolved oxygen is removed, say) it can be very different. It’s all relative to the frame of reference – the culture, the background conditions – and there’s no over-arching framework that allows us to say one system is better than another.

As the philosopher Gopal Sreenivasan points out, a touch of relativism is helpful in multicultural societies where we live alongside people with vastly different cultural and religious perspectives. At the same time, it has certain drawbacks because appeals to truth and objective facts help us resist being controlled by unjust forces.

The thought that truth is in some way essential to our ability to protect ourselves from injustice is found in the work of the political theorist Hannah Arendt. In her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt connects the blurring of fact and fiction with the rise of totalitarianism. According to Arendt, the threat of totalitarianism arises because facts constitute fixed external points with which individuals can settle disputes. If we no longer know what’s true and false, if we start acknowledging what we now call ‘alternative facts’, it’s much easier for those in power to exert their control over us.

Say, for instance, that you and I are arguing over whether or not water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen molecules. There’s a ‘fact of the matter’, here. It’s something we can go and check in a laboratory. Water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen (H2O), so the disagreement can be resolved. Imagine, however, that someone comes along and says that all chemists are untrustworthy, that molecular science is a scam. We’d be presented with ‘alternative facts’, emerging from an alternative body of knowledge. Depending on how much credence we give this person, and this ‘knowledge’, the line between what’s true and false would blur.

Arendt thinks this blurring deprives democratic societies of external points of purchase. The power to arbitrate disputes, to decide who’s right, comes to be wielded by those with the most power and the loudest voices (often the leaders of the state).

The postmodernists show us how concepts like ‘objectivity’ and ‘truth’ are used to oppress marginalized groups. It was ‘objective’ Western science, for example, that claimed that women were less intelligent than men. Arendt argues that those same concepts are essential for us to resist those same oppressive forces; science provides us with reliable, objective evidence that allows us to challenge the sexist and misogynistic views of patriarchal societies.

It may just be a matter of opinion. But wherever you finally fall, the truth is that the truth is clearly important for everyone. Whether you think truth is relative, or hard-and-fast, will affect how you converse with others.

TOOLKIT

TOOLKIT

01

Historically, the concept of rationality positions some subjects as more ‘rational’ than others. During disagreements, consider whether you and your interlocutor see each other as ‘irrational’. Are these views grounded in the argument or in how you’re behaving?

02

We typically think that groups, such as political parties, possess a ‘general will’. We tend to think they can form decisions and perform group actions. When arguing, do you see your partner as an individual or a representative of a group? Ask them how they perceive you.

03

Some people believe we’re just ‘products of our environment’ and as such completely causally determined. While it’s helpful to recognize how attitudes emerge from specific belief systems, the view that someone necessarily thinks certain things creates obstacles to conversation.

04

People often disagree about what is and isn’t ‘true’. Relativists, however, say that ‘truth’ is simply the opinion of the dominant group. When arguing, do you believe what you’re saying is true for everyone, or ‘true for you’?

FURTHER LEARNING

FURTHER LEARNING

READ

‘Descartes Was Wrong’

Abeba Birhane (Aeon, 2017)

Grand Hotel Abyss

Stuart Jeffries (Verso, 2016)

thinkingspace.org.uk

Grace Lockrobin

WATCH

Philosophy TV is a website where top philosophers beam in from around the world to disagree with each other: philostv.com

LISTEN

‘Conversations With People Who Hate Me’ podcasts. Dylan Marron frequently receives hate mail in response to his online videos. In these podcasts, he calls up and speaks to those who post negative messages.

VISIT

A governmental debate. As is the case in many countries, UK citizens and international visitors can watch politicians discuss legislation (in the House of Commons or House of Lords). Similarly, in the US visitors can visit Congress and see political debate in action.