13 SOLIDARITY

Alliance is asymmetric, solidarity is symmetric.

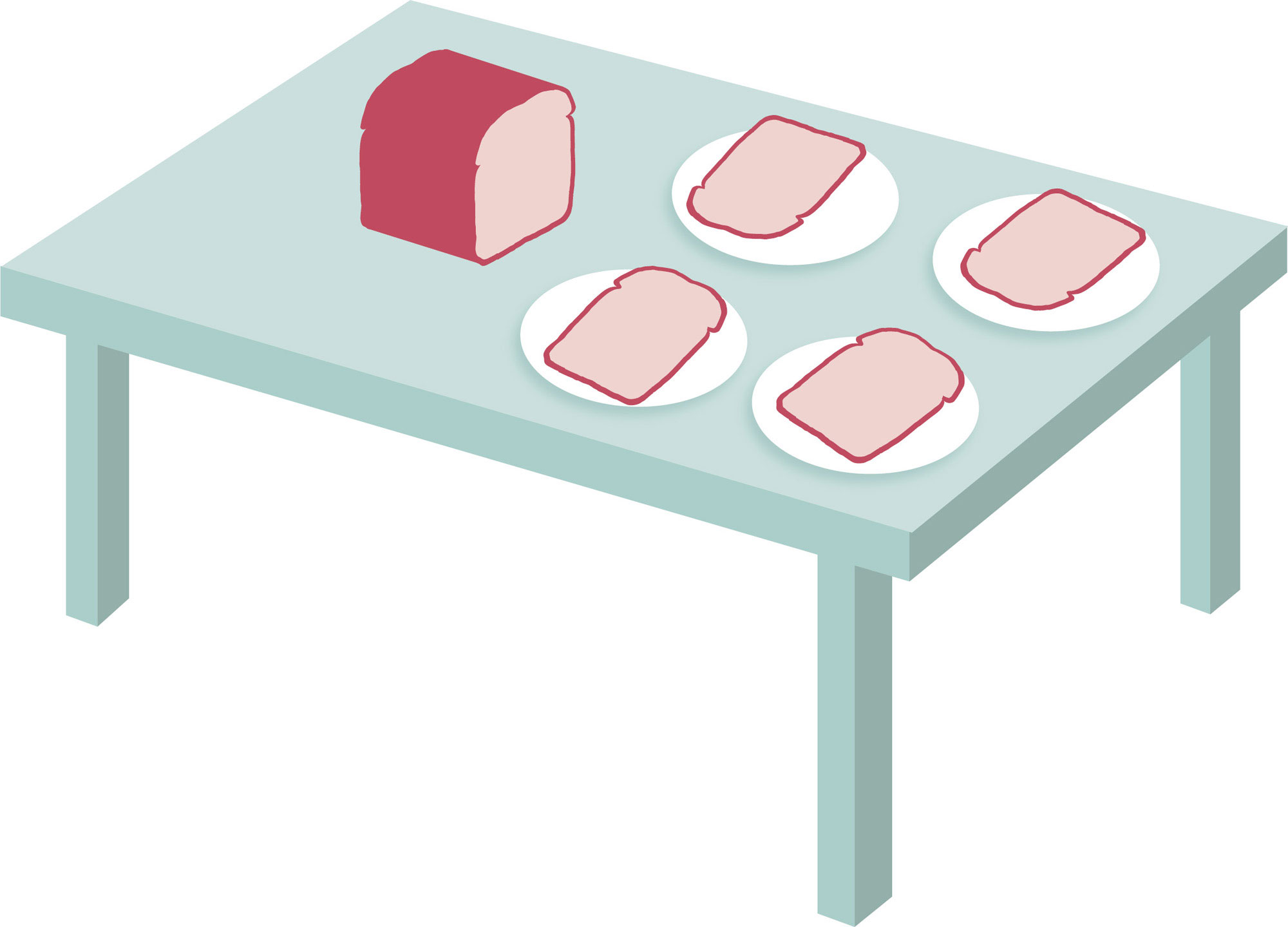

14 MEAL-SHARING

Eating together can help bridge divides.

15 HUMOUR

Jokes can bring people together or function to exclude them.

16 EDUCATION

Who performs the’epistemic labour’?

‘If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.’

Lilla Watson

Every so often we meet people who just ‘get us’. They’re ‘on the same page’, ‘the same wavelength’, we just ‘vibe’. And that’s great – it’s fantastic, really – partly because it’s so incredibly unlikely. Think about all the tiny historical details and psychological nuances that contribute to you feeling and thinking and living in the wonderfully peculiar way that you do. It’s surprising, then, given the bountiful diversity of human experience, that any two people can meet and find themselves thinking even roughly the same things.

Of course, not everyone enjoys an immediate connection. We don’t all see eye to eye. And thank goodness! Can you imagine how boring it would be if there was no diversity of opinion? This fact, however, leaves us with a puzzle. How do we get on the same wavelength as other people? What can we do to nurture productive dialogue? The aim of this chapter is to try and answer these questions.

In section 13, ‘Solidarity’, we consider two types of relationship that can hold between members of different political groups. On the one hand, people can declare themselves ‘allies’. On the other, they can declare ‘solidarity’. What do these related relationships entail? Is there something patronizing about the notion of allegiance?

Sometimes the best way to nurture connections is with a nice cup of tea and a biscuit. Section 14, ‘Meal-sharing’, examines the idea of ‘inter-dining’ and outlines the ways that communal eating can nourish mutual understanding. Meals don’t typically tend to be goal-oriented (the aim of a dinner isn’t to reach the dessert); as such they also serve as a good model for open dialogue.

Humour is the focus of section 15 – and jokes, it turns out, can be a surprisingly serious business. It’s clear there’s considerable potential for humour to create boundaries and exclude people from conversations (some individuals just don’t ‘get it’). At the same time, jokes can bring people together and create feelings of kinship and shared sentiment.

In section 16 we’re going to look at ‘Education’. The work of heavy thinking isn’t always evenly distributed (some speakers are required to do more explanatory work than others), and awareness of this is crucial for genuinely generative discussions. Here, we’re going to explore the importance of self-education. One helpful way to get on the same page as someone else is to read the same book.

Sometimes you meet someone and everything you say seems inappropriate. All your jokes fall flat. You come across as rude, insensitive or ignorant (or all of the above). In this chapter we’ll look at why this happens and what we can do to make understanding easier.

SOLIDARITY

Every year on 8 March, people around the world celebrate International Women’s Day. And every so often a well-meaning male celebrity ‘lends their voice’ to the cause and speaks up for women’s rights on large audience platforms like TV or social media. ‘It gives me a lot of hope,’ said one such celebrity, ‘to see so many women leaders finally taking their place, their rightful place, in the power structure.’ Such declarations are taken to be signs of ‘allyship’ or ‘allegiance’. (The same could be said of two men starting a section in their philosophy book with such comments about International Women’s Day.)

In social justice terms, an ally is a member of a group with a level or type of privilege who ‘stands up for’ and ‘lends their voice to’ oppressed groups who don’t have that privilege. A man championing women’s rights is one example. A white person speaking out against racism is another, as is a straight person defending gay marriage, or a member of the wealthy elite speaking for the 99 per cent.

Being an ally appears, at first, to be a good thing. Allies are well intentioned and want to help out. Their heart’s in the right place. They recognize their privileges and want to use them for good. It’s no surprise that in this example the male celebrity was celebrated as a ‘good guy’ for what he said, and for his continued commitment to gender equality.

At the same time, there’s something slightly iffy about allies. It seems a little strange that so much attention is paid to what men have said on International Women’s Day. This is an example of what Sara Ahmed calls ‘the stickiness’ of privilege. In trying to stand up for women, the male celebrity garners positive attention as a man.

The relationship between the ally and the oppressed group is problematically asymmetric – it goes one way. The power imbalance that International Women’s Day is intended to address can in fact be exacerbated by the ‘charitable’ attitude of men. The legitimacy that male allies trade on when ‘speaking for’ women can be reinforced rather than reduced by these statements of allegiance (we talk more about this in section 9, ‘Talking Over’). Irrespective of their intentions, these supposedly helpful voices are picked up and broadcast in a way that drowns out the voices of women.

In her piece ‘On Making Black Lives Matter’ (2016), the American essayist and activist Roxane Gay examines this problem in relation to ‘white allies’.

Black people do not need allies. We need people to stand up and take on the problems borne of oppression as their own, without remove or distance. We need people to do this even if they cannot fully understand what it’s like to be oppressed for their race or ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability, class, religion, or other markers of identity. We need people to use common sense to figure out how to participate in social justice.

Here, Gay problematizes the concept of an ally – but points to a related notion that may, perhaps, be more useful: Solidarity.

SHARE THE LOAD

In the mid-1980s over 150,000 miners went on strike across the UK to protest against widespread pit closures by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. These strikes lasted for over a year and Britain’s mining towns and communities suffered terribly. Throughout the industrial action, the miners received support from what was seen, at the time, to be an unlikely quarter: ‘Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners’ was a group of lesbians and gay men based primarily in London, formed to fund-raise for the striking miners. The LGSM declared their solidarity with the miners and raised considerable funds to help their cause, as well as appearing with them on picket-lines and at protests.

Solidarity is a common theme in philosophical and political works, from Aristotle onwards. It’s a specific kind of relationship that can hold between individuals and groups. As Waheed Hussain describes it in ‘The Common Good’ (2018), solidarity requires the elevation of another’s interests to the same status as one’s own. The members of the LGSM saw the governmental attacks on the miners as attacks upon themselves – the miners’ interests and concerns were treated as though they were concerns for the LGBTQ+ community (as dramatized in the 2014 film, Pride). Here, we see the realization of Roxane Gay’s demand for people ‘to stand up and take on the problems borne of oppression as their own’.

Importantly, declarations of solidarity do not require consensus. People don’t need to agree in order to act in solidarity. Solidarity typically crystallizes around particular issues, but agents need not agree on all issues. As Naomi Scheman puts it in her paper ‘Queering the Center by Centering the Queer’ (1997): ‘The issue … is not who is or is not really whatever, but who can be counted on when they come for any one of us: the solid ground is not identity but loyalty and solidarity.’

Allyship is an asymmetric relationship. It works one way; someone enters a debate and ‘helps out’ someone else. That’s why, in the face of systemic anti-black racism, it doesn’t make much sense to talk of ‘black allies to white people’. Unlike allyship, however, solidarity can be a reciprocal relationship. In 1984, the LGSM group declared its solidarity with the striking miners. Shortly afterwards, the miners marched with the LGBTQ+ community at Gay Pride and voted as a block to advance LGBTQ+ rights.

Solidarity is a powerful political force. It isn’t a matter of ‘lending your voice’ or temporarily mobilizing your privilege. It’s a matter of recognizing the ways injustices intersect, and how the fates of marginalized groups are bound together. It’s a matter of acknowledging that misogyny adversely affects men as well as women, that heterosexism damages straight people as much as gay people, that racism harms everyone, that capitalism isn’t just a problem for the poor. The word ‘solidarity’ comes from the Latin ‘solidum’, meaning ‘whole’. When you declare solidarity you position yourself as a part of a whole – and you’re all the stronger for doing so.

MEAL-SHARING

We argue over email and WhatsApp and Twitter. We argue on our mobiles and Reddit and Facebook. Technology has advanced to such an extent that we can sit in our bedrooms in Atlanta and pick fights with people sitting in their living rooms in Kuala Lumpur. We can argue without even knowing who we’re talking to.

Social media technologies have brought people together. They have great liberatory potential, linking up different folk around the globe. But they can exacerbate disagreements too. It’s harder to gauge emotional reactions, to see your respondent as a person, if they’ve been reduced to a few dancing pixels. It’s easier to caricature them, to flatten them into a stereotype, if you only have a shallow understanding of who they are and where they’re coming from.

This problem is hardly new. Communities that are geographically or socially separate inevitably tend to understand each other less well than those that exist in proximity.

The thought, advanced by the scholar-activist Nathaniel Adam Tobias Coleman, is that in order to puzzle through disagreements it’s important to be aware of these distances. People with different views and from different walks of life can profit from brushing up against each other. One of the best ways to do this, suggests Coleman, is through meal-sharing.

Meal-sharing means exactly what it says on the tin: sharing meals. In’The Duty to Miscegenate‘ (2013), Coleman examines meal-sharing, or ‘inter-dining’, as a method for tackling inter-cultural tensions. This work builds on that of Bhimrao Ambedkar, the Indian economist and social reformer who was heavily involved in campaigns against social discrimination of the Dalit caste (the ‘untouchables’) in India in the early twentieth century. In ‘The Annihilation of Caste’ (1936), he advocates regular inter-caste dinners as a means of fostering fellowship. Members of distinct castes can better understand one another when engaged in that most human of practices: getting a bite to eat.

For Coleman, the importance of inter-dining can be explained partly in relation to the symbolic power of meals; to offer someone ‘a place at the table’ is a way of expressing fellowship. It’s no accident, Coleman says, that ‘companionship’ is etymologically grounded in the Latin words ‘con’ (with) and ‘panis’ (bread). A companion is someone with whom we ‘break bread’.

The effectiveness of meal-sharing in nurturing dialogue is borne out by the science. Coleman describes various sociological studies conducted in South Africa in the early 2000s, which show that racial reconciliation between black and white South Africans was non-accidentally related to ‘inter-group contact at meal-times’. This correlates to what the psychologist Gordon Allport calls ‘the contact hypothesis’: certain forms of inter-group contact reduce the prejudices holding between them. It’s not hard to see how meal-sharing can do this. We associate eating together with intimacy. Intimacy creates companionship. Companionship is good in itself, but also provides foundations for agreement and decision-making – and that, as they say, is the icing on the cake.

‘LET’S EAT!’

Meals can bring us closer together. Office tensions can be dissolved over a plate of chips in the pub. Family discord may be soothed with an outing to the local carvery. Still, it’s not inevitable that meals are relaxing. We’ve probably all eaten in restaurants or at people’s houses where we’ve felt out of place. Maybe you have specific dietary preferences that aren’t being met? Maybe you’re confused about which piece of cutlery to use? Sometimes this discomfort is something to be avoided (we discuss this further in section 17, ‘New Spaces’), but it might not always be such a bad thing.

Going round to someone’s house for a meal can be an example of what the feminist philosopher and activist Maria Lugones calls ‘world-travelling’. Putting yourself ‘out there’, in someone else’s dining room or favourite restaurant, helps you understand ‘where they’re coming from’. Sure, it might be nerve-wracking – you might accidentally insult them or end up eating food you’re not used to – but you may also gain important insights into their world, where they’re comfortable and in control. Your anxiety can be a good sign, showing that you’re moving out of your own comfort zone and into theirs.

Lugones is emphatic in saying that world-travelling isn’t just a matter of tasting new, ‘exotic’ flavours, or indeed even literally travelling. When world-travelling, there should be genuine attempts to engage with the whole world, not just the culinary aspects. As the novelist Jamaica Kincaid puts it, it’s important to avoid becoming mere tourists, ‘pausing here and there to gaze at this and taste that’. World-travelling is about opening yourself up and appreciating all the linguistic and societal conventions that surround the meal. Of course, these conventions may make you feel uncomfortable (Are you eating this correctly? Have you mispronounced the name of the dish?), but this discomfort is the product of a disparity in world-views, your own and your host’s. The longer you sit with it the more likely you are to understand where your co-diner is coming from.

Importantly, world-travelling and meal-sharing are not goal-oriented. It’s the sharing of the meal that’s important, not the replenishing of energy. It’s about the journey not the destination. In this respect, meals serve as an excellent model for open conversation. People come together, not with an end-goal in mind, but with the hope of being in each other’s company. While arguments are often thought of as linear processes – directed towards reaching a Decision, a Solution or General Consensus – they can also be seen as opportunities to interact with and get to know other people. As Kwame Anthony Appiah puts it in Cosmopolitanism (2006): ‘Conversation doesn’t have to lead to consensus about anything, especially not values; it’s enough that it helps people get used to one another.’

A good conversation, like a good meal, isn’t something you aim to finish. It’s something you hope to enjoy.

SOLIDARITY IS A POWERFUL POLITICAL FORCE.

HUMOUR

‘I was only joking!’

That’s what people say when they’re trying to back-pedal. Maybe they’ve insulted your new haircut. Maybe they’ve made fun of your project pitch in a meeting. Maybe you tell them it hurt your feelings, it upset you, it made you uncomfortable, and maybe they shrug and say, ‘I didn’t mean it.’ Or ‘Don’t be so sensitive.’ Dismissing a statement as a ‘joke’ is often a defensive strategy, where the speaker attempts to distance themselves from the offence they’ve caused. ‘I wasn’t being serious.’

Eva Dadlez and Aaron Smuts think there’s no such thing as ‘only’ joking. Jokes, as they punctuate our everyday life, are more than mere verbal flourishes; they’re important linguistic events, often demonstrating a complex mastery of language and meaning-making. They can play central roles in group dynamics and the conversations of which they’re a part. Dadlez and Smuts’ research is part of a growing body of philosophical literature that encourages us to take joking, and humour in general, more seriously: jokes, they say, mean something.

One area that has recently risen to prominence in this literature is the ethics of jokes. To some, the phrase itself may sound like a punch-line or a category error. Jokes are just jokes, they’re not subject to ethical critique, they’re not the kind of thing that can be right or wrong or good or bad. Such deflationary thoughts lie behind defences of what many think of as ‘politically incorrect’ humour. They’re just words, the deflationist says, and as the old adage goes, ‘Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.’ When someone says ‘Can’t you take a joke?’, the implication is that ethical or moral critique of a humorous statement is inappropriate, because utterances by themselves are harmless.

Of course, anyone who’s ever been laughed at or made fun of will see the weakness of the ‘just a joke’ position. Humour can be harmful. It can create boundaries and function to exclude specific listeners. Some people are positioned as ‘in on the joke’ and others are not. Some people ‘get it’ and other people don’t.

Philosophers of language like Nadia Mehdi analyse jokes as ‘speech acts’. A speech act is a verbal utterance (someone saying something out loud) that both conveys information and performs an action. The classic example of such an act is the declaration ‘I do’ in a marriage ceremony. ‘I do’ both expresses the speakers’ agreement and it consummates the marriage. Jokes, Mehdi thinks, do things too. For instance, they can undermine the legitimacy of certain perspectives. Sexist jokes about ‘women drivers’ reinforce the sexist idea that women are less capable of driving than men. Jokes about ‘global Jewish conspiracies’ perpetuate anti-Semitism, and in turn cause listeners to ignore or fail to hear Jewish concerns about institutional anti-Semitism.

A joke need not be explicitly offensive for it to create boundaries. Think about the ‘office clown’ (there’s always one). When they joke around, some of the office personnel are ‘in on the joke’, but who’s outside it? Is the office clown making fun of someone? Does that someone feel excluded as a result?

‘GET IT?’

It is already noteworthy that we laugh at all, at anything, and that we laugh all alone. That we do it together is the satisfaction of a deep human longing, the realization of a desperate hope. It is the hope that we are enough like one another to sense one another, to be able to live together.

Jokes can exclude people. That’s the downside. They can create walls. The upside, as Ted Cohen describes above in Jokes: Philosophical Thoughts on Joking Matters (1999), is that not all walls are bad. Some provide shelter. Some boundaries bring people closer together.

Imagine walking into a meeting with a group of people you’ve never met. Before getting down to business, you engage in small-talk.

‘How was your trip?’ someone asks. ‘Did you take the train?’

You mention you flew in from Edinburgh – and add, ‘Boy, are my arms tired!’

It’s an old joke (a very old joke), and you make it because you’re nervous. Still, the others laugh. They’re laughing because they know it’s an old joke – and they’re fully aware of what a ‘dad joke’ is (the kind of joke that makes you groan rather than chuckle). Everyone’s ‘gets it’. In this situation, Cohen says, the joke serves as a conversational shorthand; it points to shared understanding that would otherwise take considerable time and effort to express. A group boundary is drawn and everyone present falls within it.

Imagine, by contrast, what happens if the joke ‘falls flat’. Perhaps it’s met with bemused scowls. ‘Why are your arms tired?’ Cohen think the sense of dislocation that results when a joke ‘fails to land’ is highly telling. It’s a failure of communication, the result of a lack of shared cultural touchstones, and as such you feel excluded. Not only do people not ‘get it’, they don’t ‘get you’.

Jokes can include or exclude listeners. They can bring people in and strengthen bonds of friendship, or they can keep people out and undermine their legitimacy. More often than not, these speech acts work differently depending on the context in which they’re uttered. A joke which involves an intimate understanding of your family history and your relationship with your mother, brother and second-cousin-twice-removed may leave your siblings in stitches and bring you closer together. If you’re talking to your siblings in front of your partners, however, cracking the same joke may create an ‘us/them’ dynamic. Insiders and outsiders.

The practice of joke-telling is a funny old business. Whether they make you laugh or not, jokes do things. Humour can marginalize and silence people – or it can nurture intimacy and a positive group identity. Whatever they are, it seems that jokes are never just jokes.

EDUCATION

Thinking can be hard work. Remember all those maths problems you did at school? Remember memorizing all those names and dates for your history exam? It’s not easy, thinking. It’s a specific kind of activity, which philosophers who like their fancy words call ‘epistemic labour’.

Occasionally, epistemic labourers are paid for their work. Published authors, for instance, are given money for thinking up thoughts and writing them down in books like this one. But thinking isn’t the easiest thing to quantify, is it? Is it? By posing this question, we’re asking you to perform a particular task – figuring out a solution – but is it the kind of task that can be measured in ‘labour hours’? How much is your answer worth? This kind of vagueness, around quantity, quality and value, can mean that thinking isn’t always construed as genuine labour. As such, it’s not always properly paid for or even recognized. Understanding this is key to addressing certain asymmetries that appear in our everyday arguments.

When confronted by the testimony of victims – of office bullying, say, or institutional sexism and systemic racism – a common response is to ask: ‘How can I help?’; ‘What can I do?’; ‘Tell me about your experience’. These are well-meaning questions, borne from a desire to improve an unjust situation. Unfortunately, they put the onus on the victims to do the work of providing an answer. As Audre Lorde puts it in Age, Race, Class and Sex (1995):

Black and Third-World people are expected to educate white people as to our humanity. Women are expected to educate men. Lesbian and gay men are expected to educate the heterosexual world. The oppressors maintain their position and evade their responsibility for their own actions …

The costs of explaining situations and thinking up solutions can be high – even higher when you’re educating someone about your own suffering. In ‘So Real It Hurts’ (2011), Manissa McCleave Maharawal writes:

Let me tell you what it feels like to stand in front of a white man and explain privilege to him. It hurts. It makes you tired. Sometimes it makes you want to cry. Sometimes it is exhilarating. Every single time it is hard.

This is an example of what the American epistemologist Nora Berenstain calls ‘epistemic exploitation’. It’s a form of coerced labour that’s typically unrecognized, largely uncompensated, and emotionally taxing to the point of being physically harmful. It’s something we need to bear in mind when engaging in difficult discussions. Are we asking too much of our interlocutors? Are we asking them to relive trauma in order to provide evidence for it? If we’re asking them to do all the epistemic labour, is that okay?

THINK FOR YOURSELF

Epistemic exploitation is a common phenomenon. In part, that’s because it’s perpetrated by people intent on ‘doing the right thing’. These well-intentioned folk think they’re ‘just asking questions’ or even ‘exercising harmless curiosity’. There’s a real possibility they might get angry at you if you accuse them of exploitation when they’re ‘just trying to help’ – a phenomenon known as ‘backlash’. These people, who exploit others, are people like us.

We exploit others without realizing, because epistemic exploitation is a crafty business. It often presents itself as neutral or even benevolent. It’s hard to pin down. We can all too easily slip into asking someone else to think for us. ‘Tell me …’; ‘Can you explain … ?’; ‘How is that even possible?’

Fortunately, there are moves we can make to avoid exploiting other people’s epistemic labour.

The first thing to acknowledge, following the epistemologist Kristie Dotson, is that the testimonies that are often called for – descriptions of prejudice and oppression, say – already exist. They’re out there, in books, magazines and online. Of course, as Dotson points out, the written words of the marginalized are often marginalized themselves – sidelined and suppressed, excluded from syllabuses and the mainstream media – and it can take an effort to learn the appropriate search terms (such as ‘epistemic exploitation’ and ‘epistemic injustice’).

Another way to address the problem is to try and disturb the concept of ‘help’. ‘How can I help?’ is a loaded question. It’s one-sided, since it suggests that the speaker exists in some way outside the problem. ‘How can I help?’ ignores the fact that systemic oppressions (racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism) are not simply problems for the people directly affected by them. Recent discussions about ‘toxic masculinity’ have demonstrated that men as well as women are affected by sexism and misogyny, albeit in different ways. There are, for instance, harmful and punishing standards of machismo to which men are expected to conform. One way for men to avoid shifting the burden of work onto women is for them to recognize they’ve got ‘skin in the game’ (for more on this, see our entry ‘Solidarity’).

Epistemic exploitation is an education issue. Those in privileged positions ask to be educated by those from marginalized groups – and this need could, and should, be met elsewhere. In addressing epistemic exploitation it pays to invest in public education. This is a central aim of recent attempts to ‘decolonize the curriculum’. Looking at school and university syllabuses around the world, activists at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London saw a paucity of texts by scholars of colour: the curriculum was ‘colonized’. It contained primarily white, male voices, talking about primarily white, male experiences of the world. This extends into secondary and primary school education as well – and the result is a gap in public knowledge about the experiences of, and theories developed by, people of colour. Bolstering our education systems will help us avoid epistemic exploitation. A useful question, then, that we should all ask ourselves is: ‘Why is my curriculum so white?’

TOOLKIT

TOOLKIT

13

Allyship involves ‘lending your voice’ to others. Solidarity involves finding common cause with them. When disagreeing with others it’s helpful to consider points of shared concern and whether you both have investment in the issue at hand.

14

Sometimes, common ground is found through simply spending time together. Views often shift slowly and indirectly, so eating with your interlocutor may be just as effective as restating your argument.

15

Humour creates boundaries that can exclude people or bring them closer together. When making jokes, consider the effect they have on the listeners. What shared assumptions are required for the jokes to work?

16

Thinking can be hard work, and difficult conversations can require a lot of ‘epistemic labour’. It’s important to consider who’s doing the heavy lifting in a conversation. How else could the ‘epistemic labour’ be distributed and how can we improve our basic education?

FURTHER LEARNING

FURTHER LEARNING

READ

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism

Robin DiAngelo (Beacon Press, 2018)

London and the 1984–5 Miners' Strike

Edited by David Featherstone and Diarmaid Kelliher (2018)

WATCH

Dwelling Together. Directed by Meghna Gupta, this YouTube film documents a 2017 project organized by Darren Chetty and Abigail Bentley, focused on exploring multiculturalism, racism and identity.

The 2014 film Pride, directed by Matthew Warchus, tells the true story of solidarity between lesbian and gay activists and Welsh miners during the 1984 miners’ strike.

LISTEN

The racistsandwich.com podcast, founded by Soleil Ho and Zahir Janmohamed, offers up in-depth discussions about the intersections between food and politics.

VISIT

London’s MayDay Rooms is an educational charity set up to safeguard archival material about collaborative social movements and political solidarity. The Rooms run regular events, exploring radical ways of disagreeing.