17 NEW SPACES

Physical space can play a role in an argument.

18 THE POWER OF QUESTIONS

Questions sometimes shut conversations down.

19 TAKING TIME

Does social media create unhelpful dynamics?

20 SELF-CARE

Self-care can be a political action.

Philosophy books can be deceptive. Open a philosophy book and you’ll find a bunch of arguments laid out neatly on a page. ‘X says this’, ‘Y says that’, ‘The perennial question about Z is such and such’. And so on. It’s easy to be tricked into thinking that arguments just float around in the everlasting ether – that thoughts can drift free of context. Don’t be fooled. They can’t. Talking about talking in the abstract is a confusion, because even with our heads in the clouds our conversations take place in the world.

Think about the last argument you had. Did it unfold in some nonsensical, dimensionless ‘nowhere’ land? Chances are it was shouted out over a kitchen table, or muttered angrily down a telephone, or grumbled on the top-deck of the bus. Conversations, controversial or mundane, exist in our daily lives. And while it may be impossible to examine all the various uncomfortable encounters we run into, this chapter foregrounds specific ‘real world’ scenarios and examines how environment affects argument. Thinking about these literal and metaphorical spaces offers up methods for ‘moving things forward’, and we’ll explore ways to shift gears in difficult conversations.

In section 17, ‘New Spaces’, the topic under discussion is veganism. How are conversations about veganism, vegetarianism and carnism affected by the spaces they appear in? Will it play out differently in an abattoir as opposed to a vegan restaurant? The physical location of a conversation clearly affects the participants’ attitudes – but how?

Section 18, ‘The Power of Questions’, looks at the mechanics of questioning, and how a well-placed query can move conversations into less stuffy environs. A question is a tool which serves multiple purposes – it can elicit information, but it can put people at their ease as well. Here we’ll look at an argument about the climate crisis, and consider how questions can help a dialogue to flourish.

In section 19, ‘Taking Time’, we revisit a theme discussed in the entry ‘Going Slowly’. We look at the frenetic, almost uncontrollable speed with which arguments progress on social networking sites, and explore the possible virtues of a position called ‘slow philosophy’ in relation to the debate about euthanasia.

In the final section of the book we’ll look at ‘Self-Care’. Sometimes – not always, but sometimes – conversations simply aren’t worth having. The emotional and psychological toll of talking to people intent on undermining you is too great, and the best thing to do is walk away. Here, we examine the costs of conversations about the social system known as white supremacy, and the political and personal utility in avoiding such discussions.

All too often, arguments flounder, or get stuck in unhelpful ruts. In this chapter, you’ll find tactics for switching things up and moving things forward.

NEW SPACES

It’s easy to argue about food. You can argue about how to prepare it (what’s the best way to cook jollof rice?) and about what tastes nasty or nice (Marmite, anyone?). You can argue about the cultural, religious, ethical, aesthetic and health dimensions of what you eat – so despite the possible benefits of ‘meal-sharing’ (as seen in section 14), it’s unsurprising that communal meals can be a source of disagreement if not downright discomfort.

Consider the following encounter. Mae, a long-time vegan, is visiting her family. She’s dreading it. Every time she goes, her parents spend ages preparing a huge dinner based on the family’s traditional Caribbean recipes: callaloo, pepperpot, roast pork and prawns in abundance. And every time she visits they have an argument about what she will and won’t eat. And every time, she and her mum, Alvita, end up saying exactly the same things.

Mae: You know I can’t eat this! I don’t eat meat! I’ve told you a thousand times, I don’t eat any kind of animal product. I’ve made a choice – I don’t want to support food industries that are based on the systematic killing of living creatures. Animals aren’t a resource, they’re sentient beings who feel pain.

Alvita: Don’t be so fussy! You know this is a family tradition. And this isn’t just any old junk food – these dishes are part of who you are. This is the food your grandparents ate, and their parents before them. It’s your history. It’s your cultural heritage. It’s part of your identity and your family’s identity.

This is a fictional scenario and conversations rarely play out in so clear and explicit a fashion. The core disagreement, however, is a familiar one.

On the one hand, Mae is advancing an ethical argument grounded in a concern for animal welfare. Like the ethicists Carol J. Adams and Peter Singer, she thinks all suffering is morally relevant, irrespective of species. Meat-eating as it figures in the food industry is premised on the instrumentalizing and mass-killing of sentient creatures. So are the dairy and egg industries. Mae doesn’t think the tasty pay-off is worth the pain. It’s a ‘utilitarian calculation’, where she weighs up possible happiness against possible suffering and sees veganism to be the most morally justifiable response.

Alvita, on the other hand, is arguing that these dishes have important cultural significance. In talking about the relevance of food to their Caribbean heritage, Alvita aligns herself with writers like Cathryn Bailey and Ruby Tandoh, who recognize the deep and meaningful ways in which what we eat constructs our identities. Bailey argues that this may be particularly important for marginalized communities whose culinary heritages are sometimes ways of marking and addressing historical oppressions.

Both Mae and Alvita make good points, which is why such arguments are so difficult to resolve. How can they productively move forward?

COMPANIONSHIP

Obviously, mealtimes can be a great opportunity to get together, catch up and have fun. Dining spaces, however, are not neutral spaces – and place has a huge role to play in how arguments, discussion and dialogue develop.

Think, for instance, how different it feels to argue in the privacy of your own home and on the top-deck of a bus. What about in a classroom and at the pub? Think about the relationship of the different people to the space you’re inhabiting. Who feels comfortable there and how does that affect what they do and don’t say?

When Mae visits her mum and dad, she enters a space where her parents ‘set the rules’. It’s the family home, and she’s the child, and certain power dynamics result. Some practices are seen to be normal (eating meat, for instance). Others (veganism) are not. Behaviour is regulated, specific family scripts are performed, and all of this affects what Mae does and how her veganism is construed. There is much less chance that she will be accused of being ‘fussy’ in a vegan restaurant where she’s paying for the meal.

Where you are can play almost as much of a role in how arguments develop as what you say.

It’s also helpful to recognize the relevance of place for Alvita’s argument. Markers of heritage can, as Bailey points out, achieve a particular importance for minority immigrant communities – especially when these communities are marginalized by wider society. While callaloo may not be regular fare in every British household, it is in Alvita’s. Traditions can nurture feelings of belonging, which are important to immigrants and other marginalized people. These arguments, then, may have a very different resonance in the Caribbean.

A family dinner may well not be the best place for this argument. Greater understanding might be generated, not through any particular argumentative strategy, but rather by a literal change in location. A request to ‘take the argument outside’ might sound like an invitation to a fight – but getting a change of scene may well be sound advice.

THE POWER OF QUESTIONS

A question is a tool that can be used for multiple purposes. That, at least, is the view advanced by the epistemologist Lani Watson in her paper ‘Curiosity and Inquisitiveness’ (2018). Watson says we use questions to get information, to communicate with one another, to express concern, to express ourselves, to make a noise – and many other things besides.

Consider the following scenario. You’re sitting in your office and a co-worker walks in and loudly declares that they’ve just booked a flight to Barbados, adding, ‘I don’t care about this climate change stuff!’

Maybe, like your co-worker, you think the climate change debate is just a lot of hot air. Maybe you nod and go about your business. Unfortunately, the scientific evidence overwhelmingly suggests that global warming is a very real and very dangerous environmental phenomenon. The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) has issued repeated warnings about the effects of air travel on sea levels and it is becoming increasingly clear that as a planet we are in a worsening state of ‘climate crisis’.

Given this, you may be troubled by your co-worker’s comments. How do you react? Perhaps you decide it’s best to keep quiet and mind your own business. Or maybe you feel compelled to interject?

‘Are you being serious?’ you ask. ‘Don’t you think the climate crisis is one of the most pressing issues of our time? Don’t you know that unless we stop global warming, the sea levels will rise, there’ll be mass flooding …’

In some ways, these questions aren’t really questions at all. ‘Are you being serious?’ is a rhetorical device that implies your conversational partner can’t actually be serious. Like ‘Are you joking?’ and ‘Are you having a laugh?’, it’s intended to discredit them. Similarly, ‘Don’t you think … ?’ isn’t really a question. It’s a way to state or restate your own position. You’re not actually trying to find out what your interlocutor thinks, you’re trying to tell them what you think – and perhaps to express horror that they don’t think the same thing.

Hearing the scorn in your voice, your co-worker may be shamed into cancelling their flights. Perhaps they’ll acknowledge the glibness of their remark and agree that global warming is not something to be spoken of so lightly. There’s a chance, however, that your arch comments may make them more defensive and, having been criticized, they may ‘double down’ on their original position. Using these kinds of non-questions is a risky strategy. Horror and scorn are not inevitably going to encourage productive dialogue.

‘CAN YOU TELL ME MORE?’

Some questions can have a positive outcome and foster understanding. In their article ‘“No Go Areas”: Racism and Discomfort in the Community of Inquiry’ (2016), Darren Chetty and Judith Suissa hone in on one question in particular: ‘Can you tell me more?’

If the conversation with your co-worker becomes difficult or uncomfortable, ‘Can you tell me more?’ might help you gain a greater understanding. Instead of asking if they’re ‘being serious’ (a non-question), you might ask them to tell you more about their views on climate change. It’s an open, genuine invitation, and unlike the rhetorical ‘Are you joking?’, it generates knowledge. Your co-worker may, for instance, respond by telling you about their views on the racial politics of climate change discourse: ‘A ban on air travel unfairly discriminates against immigrants who want to visit family in other countries. Global warming is a result of Western industrial history. Why should those who caused the problem – and who have already benefitted from these industrial advances – be allowed to ban other countries from doing the same thing?’

This is the kind of important information that can be elicited by the ‘Can you tell me more?’ question. And in contrast to ‘Are you joking?’, it demonstrates a readiness to listen, to ‘stay in the conversation’, as Lani Watson puts it. As such, the question fosters trust and reinforces the connection between the two speakers.

Chetty and Suissa also point out that ‘Can you tell me more?’ is crucially different to ‘Why’-type questions. ‘Unlike “why?”, “can you tell me more?” is not a demand for justification.’

If, in response to your co-worker’s initial comment, you were to hit them with a ‘why’ question – ‘Why do you think that?’ – you would be asking them to explain themselves. It’s a coercive, high-minded approach, which positions you as the person to whom your co-worker is answerable. And while it’s clearly important for such claims to be investigated, ‘Can you tell me more?’ is considerably more open, and will therefore generate more information and be less likely to lead to confrontation.

The asking of a genuine question also creates a greater parity between speakers. You may want your co-worker to explain themselves. You might equally be tempted, yourself, to explain why they’re wrong to have been so dismissive about climate change. As Chetty and Suissa indicate, to do so is to create another asymmetrical power relation; you are positioning yourself as ‘in the know’. Your co-worker is being positioned as someone to be ‘educated’.

When asking questions, a good ‘heuristic’ (rule of thumb) is to consider whether you understand your partner’s position well enough to repeat it back in a way that would satisfy them. This is a useful principle with which to organize the questions that you ask. You need to gather enough information before you rush to judgement and ‘Can you tell me more?’ allows you to do this, while also demonstrating trust, solidarity and a willingness to participate.

SOCIAL MEDIA CREATES VAST, FRENETIC CONVERSATIONAL NETWORKS.

TAKING TIME

These days, virtually everyone talks … virtually. A huge number of our conversations take place on social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. And they’re amazing. At the press of a button or swipe of a screen you can bundle your thoughts into tidy little packages and send them out into the infinite internet ether for millions to see and like and comment on.

Technologies like these have led to conversational networks with incredible potential. Looking, for instance, at the role social media played in the anti-government protests in the Middle East in 2010 (the ‘Arab Spring’), ethicists like Marie-Luisa Frick have suggested that such sites can work as tools for powerful collective action. The internet will set us free … or so we tell ourselves.

It’s not all roses, however. Sometimes it feels as if anything you say online runs the risk of a backlash, or at the very least a sarcastic cat video. Social networking sites are hotbeds of toxic disagreement, with users engaging in any number of fiery exchanges to the point of pure and pointless provocation (aka ‘trolling’).

A lot of sociologists think the violence of online disagreement is a function of the interface. Facebook and Twitter force us to interact in specific ways that often run counter to productive dialogue. The epistemologist C. Thi Nguyen encourages us to think about the phenomenon of ‘echo chambers’. The algorithms that organize your ‘news-feed’ build on your online preferences and present you with information that reinforces your pre-existing beliefs rather than challenging them (creating ‘echo chambers’ and ‘filter bubbles’). This – along with practices like ‘defriending’, where you silence voices you disagree with – leads to insularity and greater polarization of views (a problem touched on in section 14).

If that weren’t enough, there’s the frenetic pace of social media. How many friends do you have? How many followers? They’re all posting comments and pictures, creating what the computer scientist Paul de Laat sees as a distinctly hyperactive style of communication, privileging quantity over quality. On top of this, we’re constantly being bothered by pop-up adverts, harried by the ‘ding’ of incoming emails and tweets – and while the informational stream draws you in (it’s designed to do so), it doesn’t always foster careful analysis.

The worry, articulated by Shannon Vallor in ‘Social Networking and Ethics’ (2015), is that this emphasis on quantity rather than quality and this silencing of opposing voices damages the way we talk to one another. It frames conversations in ways that hamper ‘deliberative public reason’. It allows us to converse, but not to foster understanding.

‘TOO LONG, DIDN’T READ’

The busyness and breathtaking pace of the internet runs counter to what the philosopher Michelle Boulous Walker sees as the demand of ‘slow’ philosophy. Along with theorists like Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeber, Walker says we need to recognize the temporality of philosophical thought. Philosophy means the ‘love of wisdom’; ‘love’ suggests care and attention. The point of philosophical engagement isn’t to run through ideas, bish bash bosh, in order to come up with a quick-fix ‘solution’. The point, says Walker, is to linger over thoughts, to contemplate, reflect and to complexify rather than simplify.

Think about chocolate. If you love chocolate, you don’t just ram it in your mouth and quickly swallow. You savour it. You let it melt across your tongue. You try to figure out its various complex flavours. If you love it, you take time to appreciate its subtleties – and the same is true when you’re engaged in philosophy. Walker quotes, admiringly, from Virginia Woolf’s essay ‘How Should One Read a Book?’ (1925): ‘Wait for the dust of reading to settle; for the conflict and questioning to die down; walk, talk, pull the dead petals from a rose, or fall asleep …’

Some will claim this ruminative approach is the preserve of those with disposable time and (by association) money. Not everyone can stroll about like a literary flâneur, aimlessly wandering the textual backstreets. Moreover, urgency is sometimes required (as we discuss in section 10). Bigoted remarks need to be called out. Action needs to be taken. It might even be that certain discussions should be blocked altogether, to avoid lending legitimacy to harmful viewpoints.

Yet there is still value in slowing down. Not everyone has the resources to engage in these online discussions, which is unfair and indicative of broader social ills, but those who do will benefit from interacting more thoughtfully. This doesn’t have to mean years of careful study. It can be a matter of having a night to think something over, or a few extra minutes to read a blogpost. You’ll get a better sense of an idea – and doing so may also make you less likely to leave a rash comment and be defensive. You may not have time to pull ‘dead petals from a rose’, but letting the proverbial dust settle, and resisting the allure of quick-fire responses, may indeed help you converse more productively.

SELF-CARE

You can approach disagreements from a variety of angles. You can solicit a range of opinions, or address a background ignorance. You can move the conversation into another space, or shift the dialogue onto a different, more emotionally engaged register. You can do any number of things to improve an argument. Sometimes, however – and this is very important – you just have to walk away.

In 2017, the British journalist Reni Eddo-Lodge wrote a book titled Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. In it, she says: ‘I’m no longer engaging with white people on the topic of race. Not all white people, just the vast majority who refuse to accept the legitimacy of structural racism and its symptoms.’

She describes a widespread pattern of behaviour, which she repeatedly experienced when talking with white people about race: the ways they deny the harmful effects of institutional racism and the failure to empathize with those suffering from those effects. She analyses how the educational work is laid at the feet of the marginalized, and examines the risks these conversations pose to people of colour, who need to tread carefully to avoid provoking racist tropes like those of the ‘angry black person’. Faced with these obstacles, Eddo-Lodge made a decision to step back from these conversations.

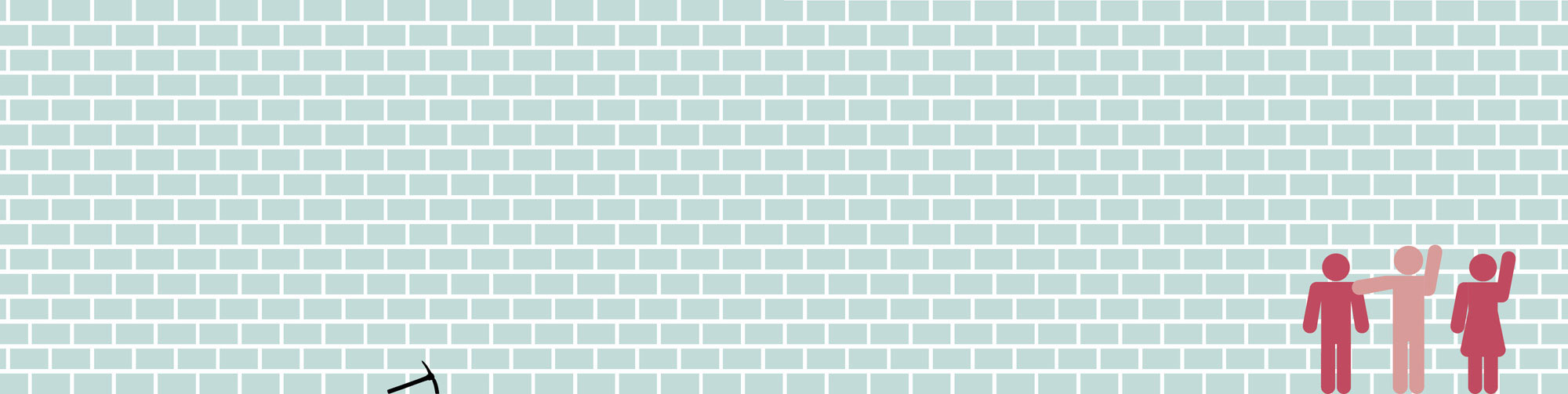

It’s this experience – of being repeatedly discredited, of being undermined and ignored – that Sara Ahmed examines in her book Living a Feminist Life (2018). Ahmed talks about ‘brick walls’. When engaging in dialogue we can ‘come up against brick walls’, and have the experience of ‘hitting our heads against a wall’. It’s a painful phenomenon – repeatedly banging into a hard, immovable object. ‘The wall keeps its place,’ writes Ahmed, ‘so it is you that gets sore.’ The institution of white supremacy holds hard and fast, and to hit it again and again can do damage.

Walls often appear in institutional contexts – the workplace or school – where someone is attempting to address or combat a problem with the status quo (in this case, systemic racism). The wall is a ‘defence system’, erected to prevent the questioning of ‘normal’ social structures, and it’s experienced by some people but not others. ‘You come up against what others do not see,’ says Ahmed, ‘and (this is even harder) you come up against what others are often invested in not seeing.’ White people benefit from institutional racism so not only are they ignorant of its effects, they are invested in its upkeep.

It’s painful and exhausting to engage in such conversations. It is draining to continually try and modify existing structures. These discussions are clearly important, but as Eddo-Lodge points out, they are also dangerous – for some participants more than others – and this makes it necessary to protect oneself. Sometimes walking away is the most sensible course of action.

‘TAKE CARE OF YOURSELF’

We live in societies riven by inequality. Do we have an obligation to stand up and call out unfair and prejudicial policies? To challenge wrongdoing? Do we have a responsibility to hold ourselves and others (including our governments) to account? On the whole, moral and political philosophers have argued that we do, but until recently few have examined how such obligations – the obligation to be ‘engaged citizens’, for instance – affect different people differently. Thinkers like Sara Ahmed and Reni Eddo-Lodge have demonstrated how some people run greater risks of ‘activist burn-out’ than others. The costs of political action are not the same for everyone. As a result, the idea of ‘self-care’ is becoming increasingly prominent in conversations about political action.

What is self-care? It’s more than a soothing bubble-bath or a relaxing evening in with your favourite TV show. It’s not just a matter of ‘looking after yourself’ and absenting yourself from boring political discourse. Self-care can, for some at least, figure itself as an act of resistance. This thought is articulated by the scholar-activist and poet Audre Lorde. In the epilogue to her essay collection A Burst of Light (1989), she writes: ‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.’

Resistance to a system of oppression is more than merely continued conversation and engagement (‘fighting the good fight’). Resistance can be a matter of survival. Extending Lorde’s thought, Ahmed says: ‘When you are not supposed to live, as you are, where you are, with whom you are with, then survival is a radical action.’ For the disenfranchised, self-care can be an act of resistance just as much as a spoken argument. The act of living in a homophobic society is a radical and dangerous act if you’re gay, just as living in Nazi Germany was a radical and dangerous act for Jewish citizens.

Sometimes the best way to change minds might not be through conversation. You can respond to an argument by stepping away from it. In addition to self-care, withholding labour can be an important argumentative move as well – especially when you’re being asked to bear too much of the conversational burden. In 2017, Eddo-Lodge announced she was going to stop talking to white people about race, and in doing so drew attention to the pervasiveness of structural racism. In 2016, Sara Ahmed resigned from her university post as a protest against institutional sexism and the reluctance on the part of her university to address it. Since 2016, feminist and pro-feminist activists have been organizing worldwide events known collectively as the ‘International Women’s Strike’, in order to protest against widespread gender inequality. These are radical acts responding to ossified and unchanging debates.

For dialogue to be productive, certain things need to be in place. Where your interlocutor is unable or unwilling to listen, or to address their own ignorance, it makes sense to preserve your energies for other conversations. One of the greatest challenges in dialogue is determining whether the conditions necessary for ‘productive disagreement’ are actually present.

TOOLKIT

TOOLKIT

17

Where you are can play almost as much of a role in how disagreements play out as what you say. Consider the different factors contributing towards disagreement (place, tone of voice, history, etc.), and whether there’s a better environment for this conversation to take place.

18

If someone says something offensive, it may be appropriate to withdraw from the conversation, but if you have the stamina, consider which questions might open up new avenues in the conversation.

19

It’s far too easy to get caught up in heated exchanges and to say things without properly thinking them through. Slowing the conversation down can help clarify a disagreement and make things more emotionally sustainable.

20

Occasionally, conversations will be too difficult to have. It’s important to recognize how much energy you have to give. Consider what’s at stake and what effect this conversation will have on your well-being. If it’s too damaging, walk away.

FURTHER LEARNING

FURTHER LEARNING

READ

Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race

Reni Eddo-Lodge (Bloomsbury, 2017)

WATCH

Do The Right Thing. Spike Lee’s 1989 comedy-drama looks at an increasingly confrontational disagreement between Italian American and Black American residents of a Brooklyn neighbourhood.

LISTEN

‘When Civility is Used as a Cudgel Against People of Color’. In this short instalment of the American podcast Code Switch (NPR), Karen Grigsby Bates looks at the ways that ‘civility’ is used to silence people of colour.

VISIT

Founded in 2015 and based in Sheffield, the Festival of Debate consists of a series of discussions, debates, Q&As and public talks examining politics, economics and society.