Also by Katharine Quarmby

Scapegoat: Why We Are Failing Disabled People

A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications 2013

Copyright © Katharine Quarmby 2013

The moral right of Katharine Quarmby to be identified as the Author of this work as been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

Extract from ‘Reservations’ by Charles Smith on p. 251 reprinted with the permission of Essex County Council.

Lyrics from ‘The Terror Time’ on p. 51 by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger reprinted with the permission of Stormking Music/Bicycle Music. All rights reserved.

‘The Act’ reprinted with the permission of David Morley.

Extract from a poem by Damian Le Bas Junior reprinted with the permission of the poet.

ISBN 978-1-85168-949-1

eBook ISBN 978-1-78074-106-2

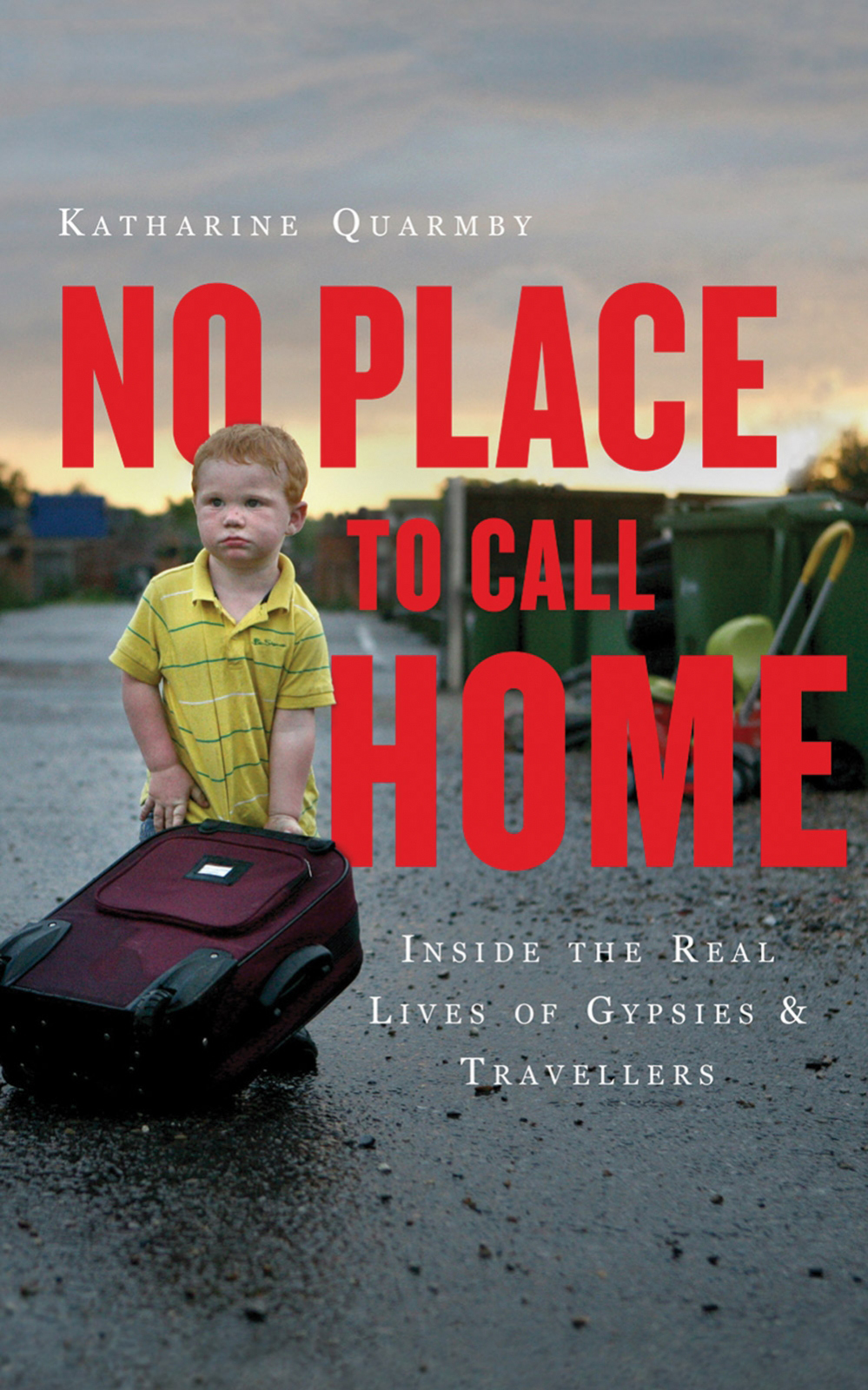

Cover design by Rawshock

Typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street, London, WC1B 3SR

United Kingdom

Contents

- Prologue

- Introduction

- 1 . ‘Chance of a Lifetime’

- 2 . Neighbours and Nomads

- 3 . Never Again

- 4 . New Travellers and the Eye of Sauron

- 5 . Things Can Only Get Better

- 6 . Payback

- 7 . ‘We Will Not Leave’

- 8 . Eviction

- 9 . Clinging to the Wreckage

- 10 . Caught

- 11 . Gypsy War in Meriden

- 12 . Targeted

- 13 . Life on the Margins

- 14 . Revival

- Acknowledgements

- Further Reading

- Notes

- Appendix

- Plates

Prologue

I drove out to Dale Farm on the morning of Wednesday, 19 October 2011, with a sick feeling in my stomach. This, at last, was eviction day for some eighty or so Irish Traveller families, after ten long years of wrangling. There were to be no more phoney wars.

The McCarthys, the Sheridans, the Flynns, the O’Briens and the Slatterys, among others, some of whom I’d first met more than five years earlier, were going to leave their beloved home, Dale Farm, with its scruffy dogs and bumpy tracks, its immaculate gated pitches and tidy caravans and chalets. Back in 2006, there had been little to no press interest in the site, and I had to persuade my editor at The Economist that this was a story worth covering. She gave me 850 words.

Now, I had to park at a garden centre a long walk down the lane because there was no room nearer to the site. The world media were there – from Japan, the US, Canada and mainland Europe. I noticed that the air smelt foul. Three helicopters hovered overhead as a plume of smoke drifted upwards from a burning caravan. A few masked protestors shouted obscenities at the police. Many of the Travellers were close to tears, although a few remained defiant. Eviction day was underway.

Mary Ann McCarthy had left the site a few weeks earlier. Grattan Puxon was holed up inside the embattled encampment and wasn’t answering his phone. Finally, two legal observers smuggled me in.

I walked round to the back, where the police and bailiffs had breached the defences at 7 a.m. I almost immediately ran into Michelle and Nora Sheridan, who were both near tears. Nora told me: ‘I saw someone being tasered: he fizzed, I tell you,’ as she tried to stop her three boys from going near the police lines. Michelle added: ‘Yes, some of them were throwing stones but it was inhumane. I was running away with a child in my arms. I was terrified.’ Tom, her youngest, who was just eighteen months old, was crying in her arms. Nearby I saw Candy Sheridan, the vice-chairwoman of the Gypsy Council, negotiating with the Bronze Commander to get an ambulance on to the site to evacuate two sick residents.

I looked around at this site that I had visited so many times over the past years. The caravan was still burning, and activists scurried around with little rhyme or reason. A community was being dismantled, real people were losing the only home they’d ever had, yet the scene was unreal, like seeing agit-prop theatre in the round. Dale Farm was a paradox – an iconic symbol of the struggle of nomadic people to find a place to call home – yet in so many ways completely different from life for most Romani Gypsy and Traveller families in the UK. What, in the end, did the battle of Dale Farm signify, and how did it connect to the wider story of the nomads in our midst, and the settled community’s relationship with them? What was this fight really about?

Katharine Quarmby

Introduction

This book is about some of the last nomadic communities in the UK – called by many names, but generically known to most people as ‘Gypsies’, a contested word that includes, in fact, many separate communities. They include the English and Scotch Romanies, the Welsh Kale Romanies, the Irish Travellers, the British Showpeople and (New) Travellers, as well as their own offshoots, including the Horsedrawns and the Boaters. What unites all of them is their struggle to survive, make homes and hold fast to cultures that often bring them into conflict with the so-called settled community.

I knew, from the moment that I was commissioned to write a book about Britain’s nomadic peoples in the wake of the eviction from Dale Farm, that I had to go much further afield to set that particular location in its rightful context as merely one part of a long and bitter struggle for Traveller sites in this country. Dale Farm was and remains highly significant, but I wanted to visit other trouble spots and interview other nomads – English and Scottish Romani Gypsies and Travellers, and even some of the newly arrived Roma, whose voices also should be heard.

This book, therefore, has its roots in Dale Farm, the first Traveller community I ever visited and of its inhabitants. But it is also the story of another site, Meriden, occupied, like Dale Farm, without planning permission, by Romani Gypsies with roots in Scotland, Wales and England. I also travelled to Glasgow, to interview Slovakian Roma, who had arrived rapidly over a few years, and agencies working with them, and travelled to both the Stow and the Appleby horse fairs to visit Gypsies and Travellers in trading and holiday mode. I went to Darlington in the North-East to visit the much respected sherar rom, elder Billy Welch, who organises Appleby Fair and has big dreams about getting out the Gypsy and Traveller vote, and to the North-West to talk to the devastated family of Johnny Delaney, a teenager from an Irish Traveller background who was kicked to death for being ‘a Gypsy’ ten years ago. I travelled down to Bristol to talk to veteran New Traveller Tony Thomson about life on the road in the 1980s, and being caught up the vicious policies of the Conservative government at that time. I also journeyed into East Anglia, where New Travellers, Irish Travellers and English Gypsies have made homes, and north of London, to Luton, to meet some of the destitute Romanian Roma who have created a vibrant community in the heart of England with the help of an inspirational Church of England priest named Martin Burrell. I was also invited to a convention in North Yorkshire by the Gypsy evangelical church, Light and Life, which is growing at an exponential rate and whose influence on nomadic cultures in the UK cannot be underestimated.

I could have travelled more – to Rathkeale, where English–Irish Travellers go for weddings, funerals and to have the graves of their ‘dear dead’ blessed once a year, or to Central and Eastern Europe, where most of the world’s Roma population (and the smaller population of Sinti and other nomadic groups) live. But I chose to concentrate on the experience of Gypsies, Roma and Travellers living in the UK – to go deep, rather than wide. But it was striking that many of those I interviewed would phone me from abroad, or from hundreds of miles away from their actual home, completely comfortable having travelled miles to find work – as long as they were with family – or were earning money to keep their family.

I’ve also looked at the resurgent creative life of Britain’s nomads – in poetry, the visual arts, drama and music. I regret not having either the budget or the time to reflect as deeply as I would have liked to on other nomadic British communities – circus and Showpeople as well as the Welsh Kale Gypsies. But their unique experiences deserve books and attention to themselves, rather than a superficial mention in this one. Of course, any book about Gypsies, Roma and Travellers cannot possibly express the depth and width of the cultures; I just hope that I have given a glimpse into a world that is not as secretive as people claim, but which is understandably private and focused on keeping close family ties alive under enormous stress.

At the heart of this book is the story of families from both Romani Gypsy and Traveller backgrounds caught up in the bitter conflicts at the Dale Farm and Meriden settlements. These families have come to public prominence over the last decade and, over the last six years, all of them have been kind enough to share some of their history with me, for which I am deeply grateful. Between them they have experienced forced eviction, racist crimes, multiple health problems, obstacles in obtaining education and, of course, life on the road, not only in Britain but abroad too. Despite all this, the families I have met have long and proud histories; they are steeped in the traditions and culture of their peoples, which they are rightly anxious and proud to preserve.

I met the Sheridans and the McCarthys in 2006, when I first visited Dale Farm. Mary Ann McCarthy was clearly the matriarch of the Irish Traveller site and, like many journalists, I was taken to see her that April. Her gentle welcome set the tone for my many encounters over the years, and I was sad to see her forced to fight for her home. I met Nora and Michelle Sheridan, who have risen to prominence among the Dale Farm community during the fight over the site clearance, on that same visit. They, like many other families, have been hospitable to me in uncountable ways, sharing their hopes and their worries about what the future holds for British nomads. I met the Townsleys and Burtons at Meriden in 2011. The Townsleys are an old Scottish Gypsy family, mentioned as far back as the time of Bonnie Prince Charlie, and after much travelling around the UK, and even as far away as Canada, put down tentative roots in the Midlands. The well-known English (and Welsh) Gypsy Burton family have traced their line back as far as 1482. The Townsleys and the Burtons are neighbours and close friends.

But these individual stories are only half of the picture. When I set out to write this book, I wanted it to move between the settled community and the nomads with whom we share this island – to give an account of the conflict that has risen between these two ways of life, and other, happier times when we have lived alongside each other in some harmony. I come from a diverse family myself – my family by birth is partly Iranian and partly English; my family by adoption, partly Serbian, Spanish and English. My Iranian birth father sailed the high seas in the Iranian Navy before being jailed after the Iranian Revolution – my birth mother was a white English girl in a seaport. My father comes from a Yorkshire farming family that can trace its roots back hundreds of years. My mother’s family is a hotch-potch of Spanish socialists, artists and Bosnian Serb nationalists, some of whom were jailed for their beliefs. She came to England after the Second World War, not able to speak a word of English. I live in the British settled community but I cherish the fact that, like many, I have roots in more than one community, both here and abroad. I wanted No Place to Call Home to speak from that middle point of view.

It has been difficult to encompass both viewpoints, however, because speaking to one side has sometimes meant the other side has sheered away from contact. This was particularly true at Meriden, where contact with the Romani families there meant that those on the other side of the fence, the residents from the settled community, felt that they would not get a fair hearing. My experience encapsulates the problem that we face: neither side feels as though it is being treated fairly. How we get over that – how we play fair with each other – is our challenge, and our necessary goal. Pitting local settled people against nomadic people (who are also often local too) benefits nobody. Both sides in this conflict have inherited a legacy of bitterness, contempt and even, in some cases, hatred between each other. But we do not have to be bound and constrained by that common past. We need to find a way to talk to each other and to move beyond our historical differences.

After all, these divisions are artificial. Since the first Roma, Irish and Scotch Travellers arrived on Britain’s shores, perhaps as long ago as a thousand years, these groups have intermarried with settled people. That practice continues today – ethnic Roma from Central and Eastern Europe are now marrying into English Gypsy and Irish Traveller families, as well as into the settled community. It is estimated that as many as thirty per cent of people in the county of Kent may have Romani blood, and similar estimates hold true in other areas, particularly in the North-East, East Anglia and around London. For all the wish to hold fast to a proud, sometimes separatist culture, DNA testing of some of the oldest Romani Gypsy families appears poised to find that these lines are heavily European, though they may well carry Asian phenotypes in keeping with their origin stories.1

As someone who is myself half Iranian and half English, I find these sorts of discoveries exhilarating rather than worrying. Not everyone feels the same about ethnic diversity, but the truth is that no pure bloodlines divide the settled community from British nomads. We all belong to these shores and may as well learn to live together, or at least alongside each other, better than we do at the moment. Indeed, most of the English and Scotch Gypsies, as well as the Irish Travellers who were born here, are more British, ethnically and culturally, than many of us in the settled community. Visiting the horse fairs where Gypsies and Travellers trade together is a glimpse into two sometimes separate cultures, but it is also a glimpse back into Old England. Once-cherished skills like riding bareback, skinning rabbits, handing down songs in the oral tradition, making pegs, cooking outdoors over campfires and trading horses, for example, are part of our ancient common culture, not skills that set Gypsies and Travellers apart from everyone else.

Despite all the grimness of the Dale Farm eviction, despite the racism that so many nomads confront, despite the contaminated conditions in which so many are forced to live because of the paucity of sites, I am hopeful. I am hopeful that things will change for the better, for all of us. This isn’t wistful optimism, however. Right back in 2006, on my first visit to Dale Farm, I was struck by the resilience, optimism and kindness of so many of the Travellers I met. More than six years on I can see change and revival at every level. The Pentecostal Life and Light church is for the Gypsy people, led by the community and increasingly self-confident about its identity. Like the black Baptist churches in 1960s America, it is giving Gypsies and Travellers the tools they need to speak out – to serve as witnesses to their condition and as actors to change it. Perhaps a leader in the mould of Martin Luther King Jnr will come from this root. The strong edicts against drunkenness, domestic violence and drugs have something of the early Methodists in them too, with their emphasis on self-reliance and pride. Many Irish Travellers maintain a strong Catholic faith – I don’t think I have ever met as many devout people as I have in getting to know Gypsy and Traveller families over the past few years.

The increasing importance that the communities themselves place on education, particularly among women and children, is heartening. Seeing Gypsy and Irish Traveller women – Candy Sheridan, Maggie Smith-Bendell, Siobhan Spencer and Janie Codona, to name but a few – speaking out about their communities and politics is truly exhilarating. The growing number of self-confident Gypsy and Traveller artists working in the visual arts, poetry, drama and music, and making international connections, has something to teach us all on this insular little island. The push by elders like Billy Welch, and influential men and women in the Irish Traveller community, including Candy Sheridan, Alexander Thomson, Pat Rooney and others to get out the Gypsy and Traveller vote, could give the communities the electoral pressure they so clearly need to push through proper accommodation and respect for their communities.

Lastly, in this book, I have used the words ‘Romani’, ‘Romany’, ‘Romanies’ and ‘Gypsy’ somewhat interchangeably. Some people from that particular community use one to describe themselves, some another. Indeed, artists, activists, academics and community members continue to debate which word they prefer to this day. A number of internationally renowned artists have now ‘reclaimed’ the word ‘Gypsy’, as they say it describes an international identity better than the words ‘Rom’ or ‘Roma’. This is not for me to judge. I have, in all cases, tried to use the words that the person used to describe themselves in each case. Any insult is inadvertent and should these choices offend anyone, I apologise.