10

Cold Skillet—Juicy Fish

Tatu the chef came back from his summer holiday with great news: now he was positive that fish should be placed in a cold, and not a preheated, skillet. “I have tested it throughout the summer. When the fish is heated along with the skillet it turns out juicier and more succulent compared with if it is put in a preheated skillet.” His observation was thus quite the opposite as compared to the instruction generally given for frying fish. And what a perfect starting point for an experiment!

For the next food workshop, Tatu bought a large salmon fillet and put it into a 10% brine solution half an hour before the experiment was to start. Together with the participants we cut out two thicker (neck) and two thinner (tail) fillets. The pieces were weighed, and their thicknesses were measured in order to ensure the pieces were pairwise as identical as possible. A kitchen thermometer was inserted in the middle of each of the thick fillets. Both thermometers had been calibrated at room temperature (20°C) and in boiling water (100°C) to ensure that any measured differences were not due to the equipment. In addition, we had a nice laser thermometer to monitor the surface temperature of the skillet.

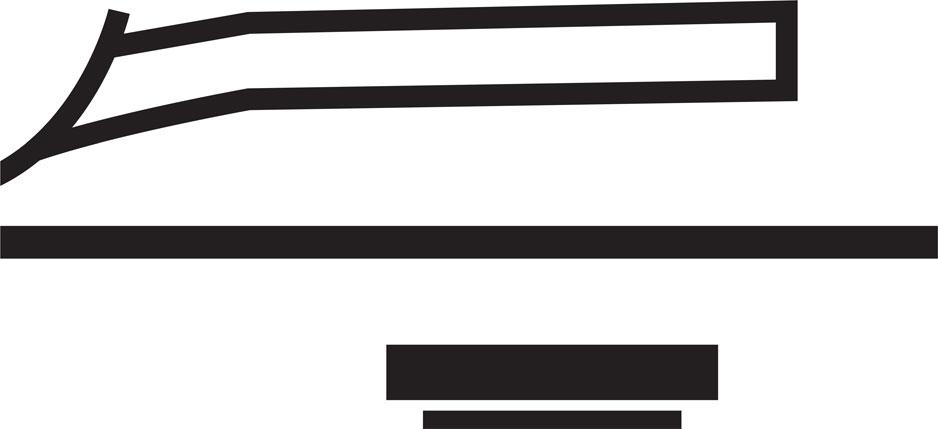

The stage was set for frying. A cold skillet with one thick and one thin fillet was placed on a preheated hotplate. After 120 seconds the temperature reached 160°C, whereby the two other fillets were placed in the now hot skillet. All four fillets were fried until the temperature inside the respective thicker piece reached 45°C, after which that pair was transferred to a separate plate, still monitoring the temperature for a few minutes. While Tatu was master of frying, two of the participants were in control of the measurements. Every 30th second, two participants monitored the temperatures in the thick fillets while two others documented the skillet surface temperature. The fifth participant planned how the measurements could best be visualized in a spreadsheet, and the rest watched eagerly. Not the most efficient use of manpower but fun it was. The temperature curves of the two versions of fish are shown in the diagram.

The pink line in the diagram shows the temperature curve of the “hot skillet” version and the blue line shows the temperature curve of the fish placed in the cold skillet. It is worth noting that the temperature continues to increase for a short while even after the pieces were removed from the skillet. We were not surprised that the curves ended up to be different, but they were opposite from what we had anticipated. To begin with, the temperature increase was highest in the fish placed in cold skillet, while evening out toward the end, and the two fillets ended up close to the same final temperature at around the same time. Weird and unexpected!

As usual in our workshops, we had to turn to discussions and review the literature to try to understand the results. We came up with three possible explanations of these counterintuitive graphs, presented below in the order of decreasing discomfort and fear:

1. Looking at the graphs, the skeptic would say that our rather relaxed experimenting group mixed the samples. Actually, we did not! We were under the close scrutiny of many critical eyes, and in this group much smaller mistakes than this are usually noticed.

2. Perhaps our thermometers were not working properly? Well, we did have quite ordinary kitchen thermometers, and the calibration procedure would not exactly stand up to scientific standards. It may also be that we did not succeed in placing the two thermometers exactly into the center of the fish samples. Definitely a weakness that asks for repeating the experiment. We are humble enough to accept this criticism as we did not bring another fillet for a second experiment. So, please go ahead and repeat our experiment!

3. Reading current literature of the field, however, indicates that there might be another explanation, and that the counterintuitive result might yet represent the actual state of affairs. In the great encyclopedias of modern cooking, Modernist Cuisine, we found a claim that placing meat onto a hot skillet might lead to formation of an insulating layer. The assumption for our subsequent reasoning would be that the same should apply to fish.

^The diagram shows the development of internal temperatures during frying. The fish placed in hot skillet actually took longer to reach the desired internal temperature (pink graph).

^The fish is fried from bottom up and at the same time from inside and out. Heat transfer occurs in different manners in the different zones of the fillet. See Chapter 9 for explanation of the icons.

The main author of Modernist Cuisine, Nathan Myhrvold, writes that a steak on the skillet, to a certain extent, is cooked from the inside out. When a steak is placed on a very hot surface, four different horizontal zones are rapidly formed from the surface touching the skillet surface and inwards: the zone closest to the skillet, the “drying zone,” is a very thin layer between the hot surface (approximately 200°C) and the food. Here, the temperature increases rapidly to pass the boiling point of water, resulting in the water evaporating quickly to give a dry surface or crust. Above (just inside) the drying zone the temperature increases to at least 140°C, enabling the Maillard browning reactions to occur (see info box). This “Maillard zone” receives heat by conduction from the drying zone. Since the temperature in this zone can reach up to ca. 150°C, water boils, rendering this zone dry as well. The next zone going inwards in the meat is a “boiling zone,” where hot water continuously evaporates and condenses, maintaining a fairly constant temperature around 100°C, and pushing steam both inwards and outwards. The steam moves mostly from below and upwards through existing and newly formed channels inside the food. Fats melt, connective tissues consisting of the protein collagen are transformed to gelatin, which can dissolve in the water. Meat proteins denature and coagulate. The meat is at the same time fried from the outside and boiled and steamed from the inside. As the steam forms new channels within the meat, the muscle fibers detach from each other breaking down the chewy structures.

Boiling of water takes a lot of energy and, therefore, the boiling zone is not very thick. Further in is the “conduction zone,” where heat principally moves via conduction as well as convection through channels in the meat. In the illustration we have envisaged that the same happens in a fish fillet as in a piece of meat.

The heat conductivity of meat and fish is rather low (see the previous chapter), and thus heat transfer by conduction occurs relatively slowly. In our study, it took 16 and 17 minutes, respectively, for the internal temperature of the fish to reach 45°C. It took a shorter time for the fish placed in the cold skillet to cook compared to the hot pan technique, but weighing revealed that both lost approximately the same amount of liquid: 11% for the cold skillet fillet, 12% for the one placed in hot skillet. The appearance of both versions was golden brown with nice crisp crust. Although the measured difference and external appearance was too marginal to indicate a difference between the two methods, again we realized that the proof of the pudding indeed lies in the tasting. All nine participants reported that they would prefer the fish placed in the cold skillet to that placed in the preheated skillet.

The Maillard reaction contributes to develop both color and flavor and is among the most important reactions in cooking. The reaction, which is in fact several parallel chemical reactions, has been named after the biochemist Louis Camille Maillard. In 1913, he published his findings on color and aroma changes when a mixture of amino acids and carbohydrates are heated in a test tube. The details of these complex reactions were not revealed until 1953, when the chemist John E. Hodge described the basic steps of the reaction. According to his descriptions, a complex multistep chain of reactions take place to produce a large number of color and aroma compounds, thereby creating the distinctive color and aroma in many of our heat-treated foods such as fried and roasted meat and fish, bread, roasted coffee, and malt for brewing and chocolate. ×

Indeed, the hot skillet version seemed to have several indications of overcooking: more white coagulant, thicker and darker crust. The thicker gray, “overcooked” layer and higher amount of coagulated protein between the muscle filaments indicates that this fish has reached a higher maximum temperature than the cold skillet version. This had happened despite the fact that the core temperature initially increased faster in the cold skillet fillet.

Our kitchen measurements did not meet the accuracy of laboratory measurements, and, thus, we only can guess what was really going on inside the fish during frying. The shorter cooking time for the fish placed in the cold skillet seems counterintuitive. But taken that the result is correct, we have a possible explanation. In a warm skillet, the surface of the fish will dry out quickly to give a dry, insulating layer. This drying zone retards heat transfer into the fillet and can increase the cooking time and give a thicker overcooked outer layer. Secondly, the boiling zone might play a role as longer cooking times should result in the boiling zone, with its high heat intensity, to be thicker (see illustration). Since we aim at an internal temperature far below 100°C, a thick layer at this temperature is not what we seek, as it would overcook the internal parts as well.

In the subsequent discussion, seven out of the nine participants said that they would hereafter place the fish in a cold skillet. The remaining two panelists stating that they would stay with the classic hot pan technique were not unmoved, though, and said that they would go for lower starting temperatures in the future.

Is it time to forget old advice on how to know when the skillet is hot enough to put the fish in and start frying? Such difficult-to-remember advice can be:

– Adjust the stove to medium heat and allow the skillet to heat up. To check the temperature, add a little water. If the water drops bounce and evaporate quickly the pan is hot enough.

– Make sure the skillet is heated to the right temperature. Too hot a skillet burns the fish but, too cold a skillet and the fish will not get the right color and crust.

– Heat butter or margarine in a sufficiently large skillet. When the fat has stopped foaming, add the fish fillets and reduce the heat slightly.

– Add a splash of oil in a dry skillet and heat it until very hot. Place two of the pieces of fish in the skillet with the skin side down first, add the other pieces after few moments. This way you avoid the skillet cooling down too much.

If our experiment is indeed correct and reproducible, you can now forget all these and other similar rules and replace them with the very simple:

– Put the fish fillets in a cold skillet and turn the heat on.

Cold-skillet Salmon á la Tatu Lehtovaara

Ingredients

150 g quality salmon fillet

1.5 g salt (ca. 1% of the weight of fish)

5 g cold butter

Black pepper

Procedure

Sprinkle the salt evenly onto the fish fillet and let it rest in the refrigerator for 30 minutes. Tap dry the fish carefully, rub the cold butter onto the skillet and place the salmon fillet in it meat down. Move the skillet to the stovetop and turn the heat on a little over half power. Fry the fish until the internal temperature is ca. 35°C, turn the fillet and continue frying until the internal temperature is ca. 45°C. Season with pepper and remove from skillet.