CHAPTER 2

ANCIENT GIANTS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN

The first duty of a man is to think for himself.

JOSÉ MARTÍ

GIANT GAULS AND GARGANTUA OF FRANCE

In 101 BCE, Roman general Gaius Marius secured two important military victories at the battles of the Aquae Sextiae and the battle of Vercellae. It was the first time in nearly a hundred years that the Romans had been able to defeat the tribes of giant Gaul warriors from southern France. During his expeditions north of Rome, Caesar continued to find various tribes of giant warriors all the way up into England. After witnessing a few battles against these burly long-haired warriors, Caesar assumed they were impossible to defeat without a massive army and advanced forms of weaponry. Diodorus, the Roman historian, described their frightening presence: “The Gauls are tall in stature, with rippling muscles . . . they are terrifying in aspect and their voices are deep and altogether harsh.”1

The giants of France were part of that larger Gaul empire that stretched into Germany and most of Europe. Eventually these ripped giant warriors that inhabited the coastal areas of the North Atlantic began to die off. As the industrial world formed, their exploits became nothing more than Druid fantasy. Then, in 1894, some of their giant kin were discovered in Montpellier, France, after workmen digging a water reservoir discovered large human skulls measuring thirty-two inches in circumference.2 Digging further down, they found bones of gigantic proportions, which they sent to the Paris Academy for a more detailed study. A scientist involved in the study believed the bones belonged to a race of men nearly fifteen feet high. Unfortunately these bones have since disappeared.

Montpellier is a few miles south of Castelnau-le-Lez, home of the legendary Castelnau giant. This eleven-foot-tall giant was known all throughout central France as being a fierce cannibalistic warlord before he died of old age and ill health. But the continual displaying of his giant eleven-foot-tall skeleton in the foyer of Castelnau-le-Lez made sure that his once feared exploits continued to haunt the locals. His legend soon slipped into obscurity and his bones vanished as the march of time moved on and the castle slipped into ruin. Then in the misty winter of 1890, French anthropologist Georges Vacher de Lapouge excavated a Bronze Age cemetery on the castle grounds that revealed three giant bone fragments. His findings were later published in the French journal La Nature. Because the bones were discovered at the bottom of a Bronze Age burial, he figured them to be at the very least of the Neolithic era. Vacher de Lapouge describes the bones in La Nature:

I think it unnecessary to note that these bones are undeniably human, despite their enormous size . . . the volumes of the bones were more than double the normal pieces to which they correspond. Judging by the usual intervals of anatomical points, they also involve lengths almost double. . . . The subject would have been a likely size of 3m, 50.3

Three and a half meters is roughly eleven feet five inches tall, a fearful height that lends credence to the old tales of the Castelnau giant spun by the locals of Castelnau-le-Lez. Since their discovery by Vacher de Lapouge the giant bones were studied in the early 1890s by prominent scientists at the University of Montpellier’s School of Medicine, who all concluded they belonged to a “very tall race.”4 A recent inquiry into these historically important bones has fallen on deaf ears, as neither the University of Montpellier nor the current residents near Castelnau-le-Lez have any idea about what has happened to them or their current whereabouts.

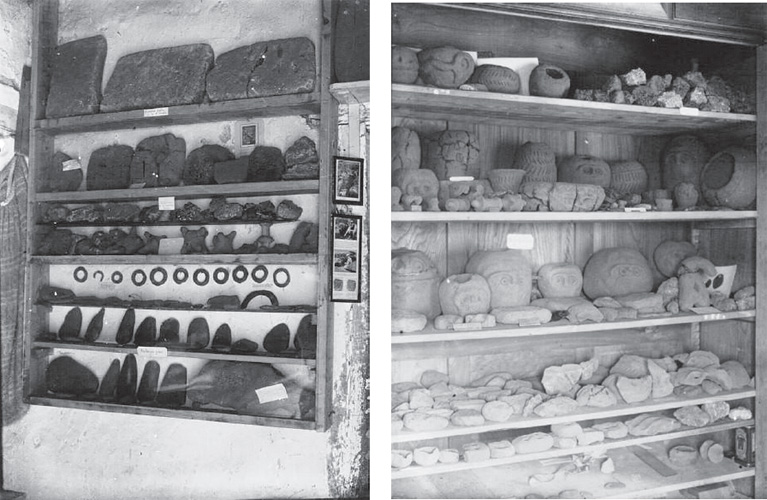

Nearby in Vichy, France, a set of handprints measuring over fourteen inches long were discovered imprinted in clay. This ancient set of handprints could have only belonged to somebody at least ten feet tall. You can see them for yourself at the museum of Glozel in a farming provence that has yielded many curious artifacts since the 1920s. Whether these “Glozel artifacts”5 are real or part of an elaborate hoax is still up for debate.

Fig. 2.1. Glozel artifacts at the museum in Ferrières-sur-Sichon, Allier, France, in 1920 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

However, one of the most popular illustrated books of all time is the sixteenth-century French tale of Gargantua and Pantagruel. Written by Rabelais and first published in 1534, the five-volume epic was inspired by the French legends of ancient giants.

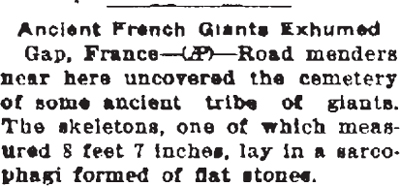

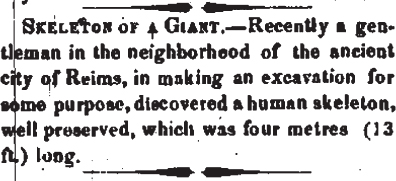

That these were more than legends is indicated by discoveries made in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In 1935, road workers in Gap, France, unearthed a cemetery of giant skeletons, the largest being eight feet seven inches in height.6 In Reims, a thirteen-foot skeleton was unearthed by a farmer in 1851.

The Miami News reported on the giant discoveries workers made in Paris in 1918:

Paris.—Military prisoners digging at Vandancourt, near Paris, discovered a tomb thousands of years old, of unpolished slabs of stone, filled with human bones of gigantic proportions. The skulls were oval and the teeth resembled those of a horse. Archaeologists say the tomb dates back to the copper age.7

A more detailed report emerged in 1933, which spoke about more giant bones being unearthed in the Paris vicinity. The Freeport Journal Standard out of Illinois reports:

SKELETONS OF SEVEN FOOT TALL GIANTS NEOLITHIC

Paris.—Paul Lemoine, the Director of the Paris Museum of Natural History, M. Lantier, curator of the archaeological museum of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Professor Rivet and other savants, have visited the tomb and all agreed it is of sufficient interest for excavation work to be continued with renewed effort. . . . Eight seven-foot skeletons were brought to light beneath a huge monolith, weighing more than four tons. A number of the bones were burnt, indicating that the bodies had been burned before burial, and little was found around them, save a few flint arrows and spearheads, which lead to the belief that the persons buried were not of very high social caste.8

Fig. 2.2. Illustration for Gargantua and Pantagruel, Gustave Dore (1873)

Fig. 2.3. “Ancient French Giants Exhumed” (Evening Tribune, August 16, 1935)

Fig. 2.4. “13-Foot-Long Skeleton of Reims” (Oswego Commercial Times, August 8, 1851)

Fig. 2.5. “Giants of Prehistoric France” (Oelwein Register, November 8, 1894)

These large out-of-place bones prompted a meeting of the Prehistoric Society of France, where prominent scientists and historians poured over the French historical records of ancient giants. It was enough to convince them that a mysterious race of giants had indeed once called the lands of modern-day France their home. This was especially so in the summer of 1935 after archaeologists unearthed another cemetery in southeast France that was home to “some ancient tribe of giants. . . . The skeletons, one of which is 8 feet 7 inches.”9

More of these giant skeletons from an unknown race prone to sleeping in stone coffins had been found in the Grenoble area of southern France in 1930. Workers digging a new road found fourteen stone coffins buried more than twelve feet in the ground as reported by a correspondent of the London Daily Mail on location in France. The slate coffins were of a prehistoric era, and the skeletons of fourteen gigantic men were revealed to have been buried there. The skulls and jawbones were double the size10 of the individuals investigating them. Most of the bones disintegrated when exposed to air, and the whereabouts of the remaining bones or coffins is not known. In the ancient French city of Reims, a well-preserved thirteen-foot-long skeleton of a giant was unearthed by farmers in 1851. It has since disappeared.11

Another legendary giant was the Germanic king Teutobochus of the Teutons, whose bones were unearthed in southeastern France, causing much fanfare and hype in 1613. In 1869, W. A. Seaver recalled the event:

In times more modern (1613), some masons digging near the ruins of a castle in Dauphiné, in a field which by tradition had long been called “The Giant’s Field,” at a depth of 18 feet discovered a brick tomb 30 feet long, 12 feet wide, and 8 feet high, on which was a gray stone with the words “Theutobochus Rex” cut thereon. When the tomb was opened they found a human skeleton entire, 25½ feet long, 10 feet wide across the shoulders, and 5 feet deep from the breast to the back. His teeth were about the size of an ox’s foot, and his shin-bone measured 4 feet in length.12

Despite the tomb and a full skeleton, modern science proclaimed the bones to be nothing more than those of a mastodon. Even still, it’s no surprise that the original giant bones of King Teutobochus have also gone missing.

SPANISH GIANTS, FROM THE CANARY ISLAND GUANCHES TO THE BASQUE JENTILS

Spain, France’s neighbor to the south, also has a prehistoric conundrum concerning ancient giants. The north of Spain has a rich tradition of giants roaming around in the days of yore. Although most pagan traditions, including tales of witches and giants, were outlawed by the church, enough of their lore survived to be orally passed down and recorded when the printing press finally came around. In the Catalonia regions ancient giants still star in many local festivals and parades, as do the “gentile giants,” as they are known in the Basque country, where folktales about them are still told to children. Basque mythology calls the giants jentil, a word similar to the Hebrew gentile (non-Jew). The megalithic stone wonders left behind in Spain were attributed to the giants, although very few have survived and most history books rarely mention them.

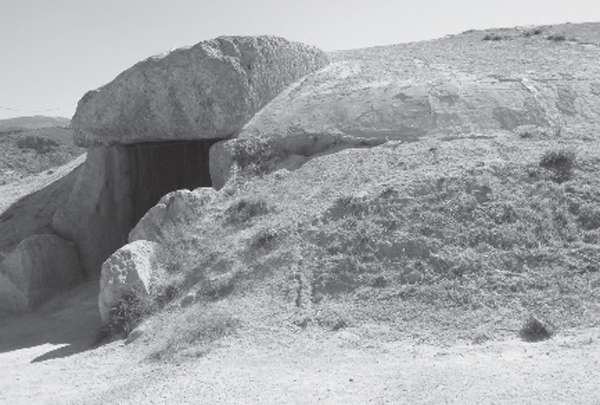

However, there is an underground megalithic cave system in Antequera, Spain (see figs. 2.6, 2.7, and 2.8). The very name of the region actually means “ancient,” validating the immense age of the mysteries found there. The Cueva de Menga dolmens complex13 is one of the largest stone structures in Europe, running more than eighty-five feet underground. It’s an archaeological wonder containing at least thirty megaliths, with an average weight each of at least one hundred tons, and quarried at the very least eight miles away.

And the world’s oldest known cave art created by Neanderthals over forty thousand years ago can be found inside the El Castillo cave in Cantabria, Spain (see fig. 2.9).14

Fig. 2.6. Antequera’s Menga Dolmen 1 (photo by Andrzej Otrębski, 2010)

Fig. 2.7. Antequera’s Menga Dolmen 2 (photo by Andrzej Otrębski, 2010)

Fig. 2.8. Entrance to Antequera’s Menga Dolmen (photo by Andrzej Otrębski, 2010)

Fig. 2.9. Cave of El Castillo in Spain, home to the world’s oldest artwork, believed to be at least 40,800 years old (photo by Gabinete de Prensa del Gobierno de Cantabria, 2008)

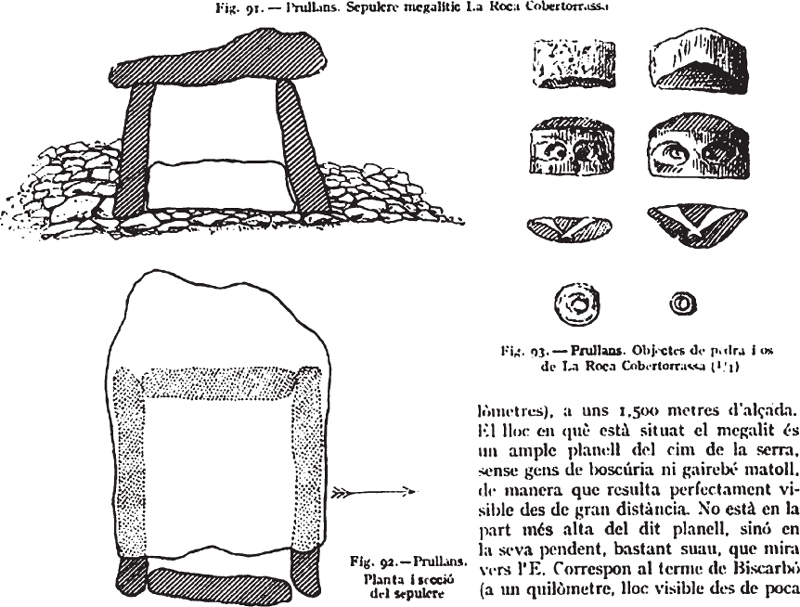

The megalithic ruins of Los Millares are another series of ancient ruins attributed to giants by the locals but claimed by academia as being the results of a more primitive Neolithic tribe. You know, because primitives had such an easy time moving one-hundred-ton megalithic blocks around with their archaic skill sets. And never mind the giant femur bone found at the megalithic dolmen site of Oren, high in the Catalan Pyrenees in 1917.15

In the Lleida Pyrenees a church restoration unearthed a ten-foot-tall giant skeleton complete with an iron nail drilled into his skull.16 A few mountains over, more giant skeletons were unearthed during another church-inspired archaeological dig, along with giant skulls found in the remaining plunders after the falling of Castile Medinaceli in the 1800s.17 The Visigothic church Marialba also revealed giant skeletons as big as those bones found during renovations at a church twenty miles away in Girona.18 In Valencia, a gigantic twenty-two-foot-tall skeleton was discovered by farmers in 1705. A giant skull was also found in the vicinity; the skull was apparently big enough to hold a bushel of corn.19

In the Spanish-controlled territories of the Canary Islands, the mysterious Guanches were an ancient race of blond-haired, blue-eyed giants whose origins were unknown. Despite being associated with Spain, the Canary Islands are situated off the coast of Western Sahara, Africa, and usually visited after hitching a boat ride from its tiny port city at Dakhla, which makes the existence of giant blond natives off the west coast of Africa even more peculiar. Soviet historian B. L. Bogayevsky claims the Guanches were the ancient survivors of the drowned Atlantis. Bogayevsky writes, “It is most probable that parts of the African continent broke away in the early Neolithic, giving rise to quite large islands. A new island, consequently, lay in the ‘Atlantic’ in front of the ‘Pillars of Hercules.’ This island, whose size popular fantasy could always exaggerate was, possibly, the Atlantis of Plato.”20

As for the Guanches, reports from the late 1890s describe them to “have been strong and handsome, and of extraordinary agility of movement, of remarkable courage and of loyal disposition; but they showed the credulity of children and the simple directness of shepherds.”21 The Guanches of the 1400s were even taller, impressing the first wave of Spanish explorers who wrote about their gigantic stature and the endless amount of brute strength they seemed to possess, claiming, “They ran as fast as horses and could leap over a pole held between two men five or six feet high; they could climb the highest mountains and jump the deepest ravines.”22 The Guanches also lived in stone houses and apparently were responsible for the megalithic dolmens and conical mounds found scattered throughout the islands.

Fig. 2.10. Dolmen of Oren, Prullans, Spain (photo by Victor Gavalda, 2012)

Fig. 2.11. The Dolmen of Oren (Institut destudis catalans seccio historico arqueologica anuari, 1921–1926, vol. vii, p.48)

Giants were also prominent figures in the legends of the Basque regions of southern France and northern Spain. Ancient Spaniards known as the Iberians have been a part of the Basque region for at least seven thousand years. With a language not related to any other Indo-European language and a genetic structure containing the rarest of blood types, these Iberians have always been considered a mysterious people. This ancient Basque race also has a detailed history of giants within their folkloric origin stories. According to the Basques, these giants were a race of tall people who loved building massive megalithic stone structures (see fig. 2.13). Eventually the giants died off and the remaining ones took to the secluded forests where they were written about by future generations as the giant “wild men” of the trees.

Fig. 2.12. Guanche engravings, Canary Islands (photo by Luc Viatour, www.Lucnix.be, 2005)

Fig. 2.13. Portable figures of giants exhibited at the cloister of the former Saint John’s Convent, currently the Basque Museum, in Bilbao (photo by Javier Mediavilla Ezquibela, 2008)