CHAPTER 3

ANCIENT GIANTS OF ITALY AND GERMANY

One of the saddest lessons of history is this: If we’ve been bamboozled long enough, we tend to reject any evidence of the bamboozle. We’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. The bamboozle has captured us. It’s simply too painful to acknowledge, even to ourselves, that we’ve been taken. Once you give a charlatan power over you, you almost never get it back.

CARL SAGAN

ITALY’S MANY TOMBS OF GIANTS

In the annals of Roman history the so-called Crisis of the Third Century (238–235 BCE) was kicked off by a giant emperor named Maximinus Thrax. Just as his name suggests, Thrax was a badass, a soldier who fought his way up from the bottom and made his way to the top of the Roman scrap heap, slowly destroying its legacy in the process. Thrax was bold, brutish, ugly as a caveman, and huge, with some sources claiming him to be over eight feet tall. He was a possible ancestor of the giant Gauls that Julius Caesar fought in France. Coins of the era depict Thrax with a massive head and the facial and skull features of a Cro-Magnon man. The historian Herodianus says that Thrax easily outwrestled and outboxed the best Roman and Greek athletes and that Thrax’s physique was unmatched in shape and size throughout the entire known world.

Thrax was a legendary commander who marched his troops deep into Germany, leading to the death of the current emperor and his family near Mainz. Thrax was now the new emperor and headed back to overthrow Rome and declare himself the new Caesar. But the giant and his troops soon became dissatisfied with their plans as weeks passed by without them being able to break the barriers of Rome’s impenetrable gates. Soon they were starved and dehydrated. The troops ambushed Thrax and his son in their sleep. Thrax’s giant head was cut off and posted high on a stake as a warning to those entering Rome.1

In the Lombardy region of northern Italy, the bones of an eight-foot-tall giant were found at the Castello di Trezzo d’Adda in 1976.2 Related to the royal lineage of the giant king Poto who ruled Lombardy circa 700 BCE, this skeleton—who was too big for the coffin he was found in—now resides in an air-conditioned vault at an archaeological museum in Milan. His giant bones are kept hidden away and not visible to the public, which seems to be the norm when dealing with giant artifacts, continuing the establishment attempts to keep the public in the dark about their existence.

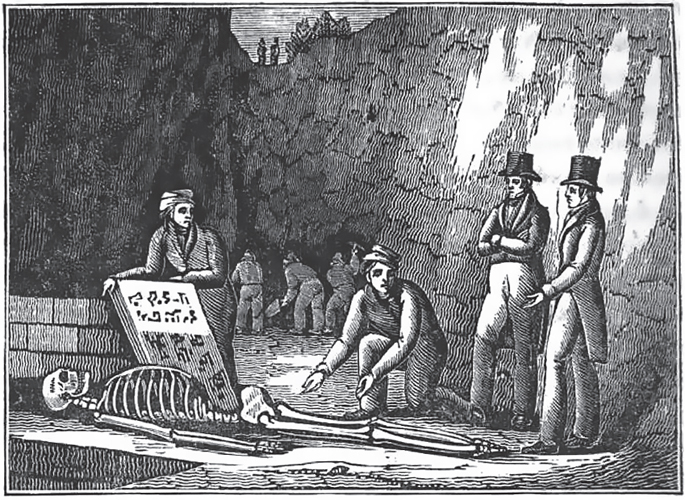

A similar discovery was made by the English captain James Allen in the summer of 1807, near the Port of Girgenti, Sicily. After skin diving for conch in the cool bay, Captain Allen and his crew went on a hike uphill to an ancient sulfur mine where they descended more than one hundred feet down, only to discover a stone sarcophagi sticking out of one of the dynamited walls. After getting the sarcophagi out of the rocks and opened up, they were astonished to find the skeletal remains of an ancient, almost eleven-foot-tall giant.3

The Barma Grande cave near the Italian border with France revealed a giant skeleton some seven and a half feet in length with one of the femur bones measuring an impressive twenty-two inches long.4 In the Sicilian capital of Palermo, a giant skeleton was unearthed by a crew of hardworking quarry men in 1516. The skeleton was said to be over thirty feet high and with a wingspan at a stunning nine feet seven inches from each point of the shoulders. A large bluish stone ax, nearly three feet long and almost ten inches thick, and weighing over sixty pounds, was found next to the sleeping giant. But in 1622 the mighty skeleton was burned into ash by a mob concerned over the Black Death spreading through Palermo (see fig. 3.2). The remaining skull was described by medieval historian Abbe Ferregus as being larger than a basket that holds a full bushel and with a jaw brimming with over sixty-four teeth confined in double rows.5

Fig. 3.1. The Girgenti 10’6″ giant discovered by Captain James Allen (as illustrated in 1807)

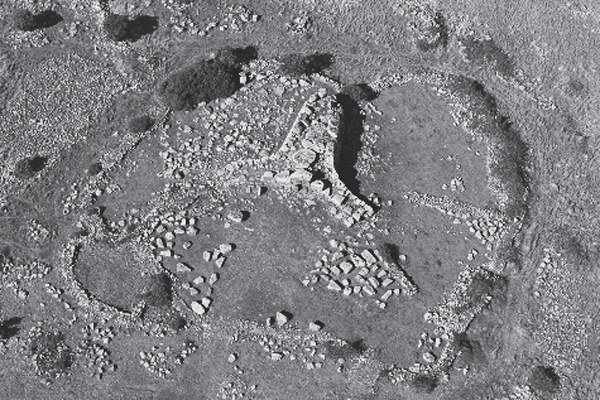

Eight-foot giant skeletons have also been discovered on Sardinia Island off the coast of Italy, home to a series of ancient megalithic grave sites known as the “Tombs of the Giants” (see figs. 3.3–3.6).

Fig. 3.2. Dolmen and tomb of a giant in Sicily (photo by Stefania Zeta, 2014)

Fig. 3.3. Tomb of a giant in Siddi, Sardinia (photo by Gianni Careddu, 2016)

Fig. 3.4. Aerial view of the Siddi, Sardinia, Tombs of the Giants complex (photo by Francesco Cubeddu, 2011)

Fig. 3.5. A giant’s tomb in Sardinia (photo by Gianni Careddu, 2015)

Fig. 3.6. Another giant’s tomb at the Li Lolghi archaeological site near Arzachena, Sardinia, Italy (photo by Pjt56, 2010)

Investigative journalist Paola Harris interviewed Luigi Muscas on his property near Cagliari, Sardinia, during the fall of 2012. Harris writes:

Luigi told me about the tombs and artifacts of giants (15 foot tall beings) who lived in Sardinia thousands of years ago. He told me that his father and his uncles, who also own land near his land, have dug up many bones and human artifacts. He also mentioned that traditional archeology does not accept this discovery and that his entire family has been threatened. He has been told over and over to keep this secret and not talk to the general public.6

Fig. 3.7. Interior of the tomb of a giant in Cagliari (photo by Fois Luigi, 2016)

Fig. 3.8. Tomb of a giant in Cagliari (photo by Fois Luigi, 2016)

Fig. 3.9. Tomb of giants on the western slopes of the Sette Fratelli, in the municipality of Quartucciu, Sardinia (photo by Alex Follesa, 2012)

Caesar Augustus once recruited two towering ten-foot-tall giants, Posio and Secundilla, to lead the Roman armies into battle. After their victory the giants were celebrated as heroes, documented by Pliny. Because of their remarkable height they were preserved in the tombs of Sallust’s Gardens. In 105 BCE, the Roman armies of Caepio and Manlius struggled mightily against a large tribe of roving German giants along the river Rhine. The bloodshed was brutal, leaving only twelve Roman soldiers who lived to tell the tale.

GERMANY: BAVARIAN CATACOMBS AND RHINELAND GIANTS

Giants are a common theme in the folklores and histories of Germany, too. The mystical realms of the Bavarian forests have spawned numerous tales of larger-than-life characters (see fig. 3.10). In the beer-guzzling town of Munich, workers unearthed forty well-preserved skeletons in a sand pit. The skeletons each averaged around seven feet in height and were accompanied with primitive stone tools.7 This discovery in 1934 was soon forgotten as no other updates surfaced concerning the skeletons. Then in 1987 a pair of fishing teenagers discovered the femur joint of an apparent nine-footer resting at the bottom of the Rhine River. This area of Rhineland had been written about by Dutch scholar Dr. Jan Albert Bakker, in his book Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547–1911. He described the giants of the Rhine as nearly naked wild men always carrying large clubs and eager to fornicate in public.

A Bavarian catacomb revealed thousands of giant bones arranged in a ritualistic method and buried under hundreds of normal-sized bones that had been set on fire at some point in the past. Known as the Breitenwinner Cave, news of the giant bones discovered there was first reported on by Berthold Buchner, the explorer who found them in 1535. Buchner, who was inspired by legends of a secret city of giants that lay beyond the massive underground catacombs as told by the citizens of Amberg, assembled a team and went to explore the catacombs. They eventually gained entrance and, throwing caution to the wind, began to explore the mysterious and darkened Breitenwinner Caves. Buchner writes:

Fig. 3.10. Legends of the Rhine, Helen Adeline Gruber (1929)

One of the leaders went in first, the other leader brought up the rear. We secured the entrance with rope and marked it with signs to avert danger, because if we should lose track of the ropes it would have been impossible for us to get out again. After fastening the ropes to a rock we descended 500 klafters [950 m] deep. Four honest strong men were selected to keep watch at the mouth of the mountain cave. Very soon we arrived at a very narrow cleft. One of our companions, a goldsmith, who at home had desired to be the first one in the cave, was so frightened by the sight of it that he deserted us notwithstanding his promise. But we crept on our stomachs some fifty Klafter [95 m] through this narrow cleft. There was a wider opening next to it but it did not stretch very far. First of all we came upon a wide space like a hall for dancing. When we crept in we found so many bones that the first of us had to pile them up in one place to make room for us to enter. The bones were very large as if from giants. We then reached a very narrow hole and had to squeeze through on our stomachs. At 200 Klafter [380 m] one comes into what seems like a beautiful spacious palace big enough to hold about 100 horses. It is lined at the top very handsomely with “grown” stones [speleothems]. There are eight or ten “grown” pillars and good seats at the sides. Here we found two skulls which to our surprise were enclosed by the rock, we could hardly hack them out with our tools. Each person took a piece, one the cranium, one the teeth, etc. There were many passages here and everywhere in the mountain; some of them we explored. All the caves and passages were full of big bones.8

In the 1970s two explorers relocated the cave, but said floods had made a mess of the place and there weren’t any more giant bones lying around. And no mention of the giant dining hall carved elegantly within the walls of the mountain interior either.

About twenty elongated skulls were discovered in the Bavarian forests of southwest Germany in the 1980s. One of the elongated skulls is on display at the local museum in Tuchersfeld.9 Armor belonging to a warrior at least eight feet tall can be seen in Reichsburg’s castle.10

Ancient historian Strabo identified the German giants who lived east of the Rhine as being more wild, blonder, and taller than the giant tribes of Celtic warriors that inhabited northern Europe. These blond German giants were eventually eradicated just like their ancestors were.

Fig. 3.11. A giant zweihänder (two-handed sword) in the historic town hall of Münster, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (photo by Anaconda74, 2013)

Fig. 3.12. German Giant of the Rhine, Bethoven M. Tiano (2016)

Fig. 3.13. Celtic megalith in Germany, Saarland, near Scheiden (photo by Frabron, 2013)

But before these tall, wild, yellow-haired giants were destroyed, according to Strabo, they were declared to be the Germani to indicate that they were the authentic, the genuine, in a sense the original true giants. Their customs were much different from the Gauls and others who fought against them. Their whole life centered on hunting and military pursuits, and they showed little interest in religious matters or rituals.

The Romans fought against these fierce Germani giants for nearly three centuries. This experience taught the legionnaires to be an effective military force. Once they fought the Germani, they could not imagine anything worse.