Ike and Sergeant Moaney grilling steaks. (illustration credit 23.1)

Our most valued, our most costly asset is our young men. Let’s don’t use them any more than we have to.

—DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER,

March 17, 1954

The Eisenhowers, like the Roosevelts, were accustomed to servants. When Eisenhower got out of bed each morning, Sergeant Moaney held the president’s undershorts for him to step into. When Ike took practice shots on the South Lawn, Sergeant Moaney retrieved the balls for him. And when Ike cooked stew for his friends, Sergeant Moaney assembled the ingredients, chopped the meat and vegetables, and stood by like a surgical assistant to hand Eisenhower whatever he required.

Mamie was pampered equally by her personal maid, Rose Woods. Rose rinsed out the First Lady’s stockings and underwear in the bathroom every night and dressed her in the late morning. Sergeant Moaney’s wife, Delores, served as the Eisenhowers’ personal cook and maid in the family quarters of the White House, and Sergeant Leonard Dry drove for Mamie. Elivera Doud, Mamie’s mother, lived in the White House, just as Madge Wallace, Bess Truman’s mother, had done, and as Marian Robinson, President Obama’s mother-in-law, currently does.1

Mamie’s experience running large household establishments was immediately evident. “She appeared fragile and feminine,” said White House chief usher J. B. West, but “once behind the White House gates she ruled as if she were Queen.”2 Unlike Eleanor Roosevelt, Mamie paid close attention to the White House menu. Although she had never learned to cook herself, she had an instinctive understanding of the compatibility of various dishes, and chided the staff to avoid waste. Every morning she asked for a list of food that had not been eaten the previous day. “Three people turned down second servings of Cornish hen last night,” she reminded Charles Ficklin, the White House maître d’. “Please use it in chicken salad today.”3

Ike and Sergeant Moaney grilling steaks. (illustration credit 23.1)

Official entertaining at the White House was straitlaced. The food was superior to that served by the Roosevelts, but the drinks were sharply rationed. Cocktails were never served, and butlers poured only American wines at the table with dinner. Alcohol flowed more freely in the family quarters. Eisenhower preferred scotch, and Mamie liked old-fashioneds, although, as J. B. West reports, her consumption was very modest despite rumors to the contrary.4

Mamie’s particular passion was watching television soap operas, and she rarely missed an episode of CBS’s As the World Turns. After her private time watching television, Mamie would be joined by her old friends from wartime Washington in the Monroe Room for an afternoon of Bolivia, a form of canasta that she adored. According to West, “The Bolivia players usually took a break for tea at 5:00 p.m., and sometimes they would stay for dinner.”a In the evenings the Eisenhowers and their guests would often watch movies in the White House theater. Ike’s taste ran predictably to Westerns, most of which he had seen three or four times. Unlike Eleanor Roosevelt and Lady Bird Johnson, Mamie did not take up public causes and rarely ventured outside her role as the president’s wife. “I have but one career,” she often said, “and its name is Ike.”5

Once a month Eisenhower would host a stag dinner for sixteen or so guests, bringing together men from various professions whom he had read about and wanted to meet. Dress was usually black tie, and the conversation was free-flowing. “I used these dinners to try to draw from leaders in various sections of American life their views on many domestic and international questions,” said Ike. “The stag dinners were, for me, a means of gaining information and intelligent opinion as well as enjoying good company.”6

Eisenhower’s concern for appearances sometimes led him to make fussy decisions. Allegedly to save money he shut down the presidential winter quarters at the Key West Naval Station and got rid of the Williamsburg, the presidential yacht on which the Trumans often entertained. “The very word ‘yacht’ created a symbol of luxury in the public mind,” Ike wrote his friend Swede Hazlett.7 At the same time, Eisenhower permitted Arthur Summerfield, the Michigan GM dealer who served as postmaster general, to repaint the nation’s mailboxes and postal trucks from traditional post office green to a car salesman’s red, white, and blue—supposedly as a symbol of American patriotism.8

“Shangri-La,” FDR’s rustic retreat in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains, which the WPA had built in the 1930s, also went on the chopping block.b But Mamie intervened, insisted that it be updated and redecorated, and used as a weekend getaway until the farm at Gettysburg could be rehabilitated. Like Key West, Shangri-La was maintained by the Navy, and as J. B. West writes, “Soon came the order for the Navy to redecorate Shangri-La, with Mrs. Eisenhower as the consultant, and the rustic lodge soon took on a ’1950s modern’ look, in greens, yellows, and beiges.”9 When it was finished, Eisenhower renamed it “Camp David” in honor of his five-year-old grandson, evidently hoping to erase the memory of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The Eisenhowers occasionally used Camp David as a retreat and conference center, but Ike much preferred to accept the hospitality provided by his friends in the Gang, with whom he felt he could best relax. His favorite spot was the Augusta National, and he used his trips to Augusta to unwind, much as FDR had done at Warm Springs.10 Eisenhower also enjoyed extended fishing vacations at Aksel Nielsen’s estate near Fraser, Colorado, and at Denver developer Bal Swan’s purebred Hereford ranch on the north fork of the South Platte River.

Above all, Ike and Mamie were soon caught up restoring the farm at Gettysburg they had purchased in 1950. After Eisenhower left the Army, he and Mamie began looking for a place to retire. They wanted a place in the country, preferably with a few acres, and not too far from Washington or New York. Gang member George Allen, a country boy from Mississippi, owned a farm near Gettysburg and recommended the region to Ike. Eisenhower had served two years at Camp Colt (on the Gettysburg battlefield) during World War I, and had never forgotten the lush rolling countryside. Mamie remembered the friendly townspeople. When Allen told them that a 189-acre farm had been put on the market, Mamie went to inspect it and fell in love with the property.

“I must have this place,” she told Ike.

“Well, Mamie, if you like it, buy it.”11

The property, known as the Allen Redding farm, was adjacent to the battlefield and about three miles from town. During the Battle of Gettysburg the house had served as a dressing station for Confederate wounded. Eisenhower paid a total of $40,000 ($362,000 currently): $24,000 for the farm, and $16,000 for the livestock and equipment. In addition to the two-story brick farmhouse, there was a massive wooden barn (one of the largest in Adams County), thirty-six Holstein dairy cattle, and five hundred white leghorn chickens. It was a working farm. The milk was picked up every morning by a Baltimore dairy, and the eggs (about twenty dozen daily) were marketed through a cooperative in Gettysburg. There were also two tractors and all the machinery necessary to operate the farm.12

Eisenhower, who was then president of Columbia, decided to retain the farm as a going concern. An old Army associate, retired brigadier general Arthur Nevins, who had been Ike’s deputy G-2 at SHAEF, was talked into becoming the farm’s manager, and General Nevins and his wife, Ann, moved into the house in the spring of 1951. The Nevinses and the Eisenhowers had been close friends since their service together in the Philippines.13

Ike and Mamie decided to renovate the house after they moved to Washington. Plans were drawn by Penn State architecture professor Milton Osborne, Mamie engaged interior designer Dorothy Draper, and the construction work was handled by Charles Tompkins, one of the largest contractors on the East Coast. Eisenhower insisted on using union labor, which meant that most workers had to drive from Washington or Baltimore, which added considerably to the final cost. On the other hand, Charles Tompkins charged no overhead and billed Ike only for actual expenses, which balanced things out.

When the project was completed in 1955, little remained of the original house. There were now fifteen rooms, eight baths, a thirty-seven-by-twenty-one-foot living room, and an oak-beamed study for Ike. The total cost came to $215,000 ($1.75 million currently), and was paid largely from the receipts Eisenhower realized for Crusade in Europe.14 Shortly afterward, Gang member W. Alton “Pete” Jones (president of Cities Service Company) bought three adjoining farms on which he planted hundreds of strategically sited trees to assure Ike’s privacy.15 The farms were combined and worked under the supervision of General Nevins. Ike raised purebred Angus cattle in partnership with Alton Jones and George Allen, but the venture was primarily a hobby rather than an attempt to turn a profit.16 Toward the end of his presidency, Eisenhower purchased an adjacent five acres containing an abandoned rural schoolhouse. The schoolhouse was remodeled to provide a home for John, Barbara, and their four children, and a private road was built connecting the two houses. Eisenhower doted on his grandchildren, and could never see enough of them.c

But Ike’s time was limited. His first priority as president was to make peace in Korea. His second was to balance the budget. Unlike the Republican party’s Old Guard, he ruled out any reduction in social programs. Savings would be achieved through the elimination of government waste and a review of all other programs. National security, the largest budget item, was an obvious target, and when Ike took office, he ordered an immediate review of the nation’s military structure.

Eisenhower was critical of existing defense policy for two reasons. First, he believed President Truman had demobilized the armed forces too quickly after World War II, withdrawing from Korea and thus inviting attack. Second, after the Korean War started, the Truman administration quadrupled defense spending without considering the costs. That threw the budget seriously out of kilter. What was required in Ike’s view was a defense policy that could be sustained over the long run without sending the country to the poorhouse.

Ike and John with David, Susan, and Barbara Ann at Gettysburg. (illustration credit 23.2)

Eisenhower was uniquely qualified to lead the reappraisal. With the possible exception of Ulysses Grant, who confronted different but equally difficult military issues, no president has been better equipped by outlook and experience to deal with matters of national security. Like Grant, Ike was his own military expert, and as with Grant the country trusted him implicitly. Both Grant and Eisenhower twice won elections by massive margins because the electorate had confidence in their abilities to defend the nation. In Grant’s case, the danger pertained to Reconstruction and restoring the Union. In Ike’s case, it was a Cold War that might turn hot. Here lay Eisenhower’s supreme personal expertise, and he tackled the issue with enthusiasm.

In his first State of the Union message, two weeks after assuming office, Eisenhower told Congress that “to amass military power without regard to our economic capacity would be to defend ourselves against one kind of disaster by inviting another.”17 Shortly afterward, he took the issue to the country. Speaking to a national radio and television audience on May 19, 1953, Eisenhower said, “Our defense [policy] must be one we can bear for a long and indefinite period of time. It cannot consist of sudden, blind responses to a series of fire alarm emergencies.” The United States could not prepare to meet every contingency, said Ike. That would require a total mobilization that would “devote our whole nation to the grim purposes of the garrison state. This, I firmly believe, is not the way to defend America.”18

Eisenhower announced that he intended to direct 40 percent of the upcoming defense budget to the Air Force. The Army and Navy would be reduced accordingly. The object was to prevent war, not to fight one. With the war in Korea approaching an end, there was no reason to maintain an Army of twenty divisions. The implication was clear. Under Ike there would be no limited wars, no police actions, no conflicts beneath the nuclear threshold. “Our most valued, our most costly asset is our young men,” said the president. “Let’s don’t use them any more than we have to.”

Ike put the matter in personal terms. “For forty years I was in the Army, and I did one thing: study how you can get an infantry platoon out of battle. The most terrible job in warfare is to be a second lieutenant leading a platoon when you are on the battlefield.”19

The Pentagon pushed back. Omar Bradley, still chairman of the Joint Chiefs, told the National Security Council that the United States had to prepare for both conventional and nuclear war. “The build-up of the military strength of the United States is the keystone and indeed, the very life blood of the free world’s strategy to frustrate the Kremlin’s designs,” wrote Bradley. To cut military spending as the president proposed “would so increase the risk to the United States as to pose a grave threat to the survival of our allies and the security of this nation.”20

Eisenhower was unswayed. The Joint Chiefs were seeking to fight a war; he was determined to prevent one. And their parochialism was appalling. In a letter to his friend Swede Hazlett, Ike noted that the Joint Chiefs had a lot to learn. “Each of these men must cease regarding himself as the advocate for any particular Service; he must think strictly and solely for the United States. Character rather than intellect, and moral courage rather than mere professional skill, are the dominant qualifications required.”21

Ike fretted about the chiefs’ recalcitrance. “Someday there is going to be a man sitting in my present chair who has not been raised in the military services and who will have little understanding of where slashes in [the Pentagon’s] estimates can be made with little or no damage. If that should happen while we still have the state of tension that now exists in the world, I shudder to think of what could happen to this country.”

Eisenhower told Swede that his “most frustrating domestic problem” was with the leadership of the armed services.

I patiently explain over and over again that American strength is a combination of its economic, moral and military force. If we demand too much in taxes in order to build planes and ships, we will tend to dry up the accumulations of capital that are necessary to provide jobs for the millions of new workers that we must absorb each year.… I simply must find men who have the breadth of understanding and devotion to their country rather than to a single Service that will bring about better solutions than I get now.22

By the end of the summer of 1953, each of the Joint Chiefs had been replaced. Eisenhower did not relieve any, but as their terms expired they were not reappointed. Admiral Radford replaced Bradley as chairman, Matthew Ridgway succeeded J. Lawton Collins as Army chief of staff, Admiral Robert B. Carney replaced William Fechteler as chief of naval operations, and Nathan Twining followed Hoyt Vandenberg as Air Force chief of staff. Ike spoke with each before appointing him, and each assured Eisenhower of his support.

With his military team in place, and after extensive staff studies, Eisenhower was ready to act. At the beginning of December 1953, the president wrote budget director Joseph Dodge that he had instructed Secretary Wilson “to establish personnel ceilings in each service that will place everything on an austerity basis.” Ike said the forces in Korea should be kept at full strength, as should the Strategic Air Command and the various interceptor squadrons, but that everything else should be reduced across the board. “We are no longer fighting in Korea, and the Defense establishment should show its appreciation of this fact without wailing about the mission they have to accomplish.”23

As a result of Eisenhower’s directive, the Army was reduced from 1.5 million men in 1953 to 1 million by June 1955. The Navy and Marine Corps shrank from 1 million to 870,000, while the Air Force increased from 950,000 to 970,000.24 Admiral Radford announced the shift in a speech to the National Press Club on December 14. Radford called the change a “New Look” in defense policy, using a term then in vogue in the fashion industry to describe the lengthening of women’s skirts. Journalists labeled it “more bang for the buck.”25

Eisenhower directed Secretary of State Dulles to put the shift in context. In a major speech to the Council on Foreign Relations on January 14, 1954—a speech that had been carefully vetted by Ike—Dulles explained the strategic significance of the New Look. Paraphrasing Eisenhower’s views, Dulles said, “Emergency measures are costly, they are superficial and they imply the enemy has the initiative.” The new aim of American policy, he said, was to make collective security more effective and less costly “by placing more reliance on deterrent power, and less dependence on local defensive power.” Dulles explained why the shift was necessary. “If the enemy could pick his time and place and method of warfare, then we needed to be ready to fight in the arctic and in the tropics; in Asia, the Near East and in Europe; by sea, by land, and by air; with old weapons and with new weapons.” But that was now changed. The United States would deter wars rather than fight them. “The basic decision was to depend primarily upon a capacity to retaliate instantly, by means and at places of our choosing.” That sentence had been added by Eisenhower when he reviewed Dulles’s original draft. The handmaiden of the military’s New Look was instantly dubbed the “doctrine of massive retaliation.” Dulles was given credit for the statement, but the words belonged to Ike.26

At his press conference the following day, Eisenhower was asked to comment on Dulles’s remarks. Not surprisingly, Ike declined. “I think no amplification of the statement is either necessary or wise,” said the president. “He was merely stating what, to my mind, is a fundamental truth and really doesn’t take much discussion; it is just a fundamental truth.”27

Other administration figures were less reticent to chime in. Treasury Secretary George Humphrey said the United States had “no business getting into little wars. If a situation comes up where our interests justify intervention, let’s intervene decisively with all we have or get out.” Nixon said, “Rather than let the Communists nibble us to death all over the world in little wars, we would rely in the future primarily on our massive mobile retaliatory power … against the major source of aggression.”28

But the New Look was not embraced by everyone within the administration. General Matthew Ridgway, although he initially signed on, soon became restive. Testifying before the Senate Appropriations Committee in January 1955, Ridgway criticized the ongoing reduction in Army ground forces. The New Look, he told senators, was forcing the United States into an “all or nothing” posture and would expose the country to a series of future Koreas. “The foot soldier is still the dominant factor in war,” said Ridgway, “and weakening our ground forces would be a grievous blow to freedom.”29

When Eisenhower met with the Senate Republican leadership the next day, he was asked by Senator Styles Bridges of New Hampshire how they should handle Ridgway’s testimony. “Ridgway is the Army’s chief of staff,” said Ike.

When he is called up on the Hill and asked for his personal convictions, he has got to give them. But we must realize that as commander-in-chief, I have to make the final decisions. I have to consider—which the heads of the services do not—the very delicate balance between the national debt, taxes, and expenditures. Actually, the only thing we fear is an atomic attack delivered by air on our cities. God damn it, it would be perfect rot to talk about shipping troops abroad when fifteen of our cities were in ruins.

That’s the trouble with Ridgway. He’s talking theory—I’m trying to talk sound sense. We have to have a sound base here at home. We have got to restore order and our productivity before we can do anything else. That’s why in our military thinking we have to put emphasis on two or three things first. One, we have to maintain a strong striking retaliatory Air Force and secondly, we have to build up our warning system so that we can receive as much advance notice as possible of any attack.

Press secretary James Hagerty, who was at the meeting, said the senators listened with rapt attention. “You could hear a pin drop in the room. He [Eisenhower] pounded the table a few times for emphasis, and everyone in the room realized both the seriousness of the situation and the President’s arguments.”30

When Ridgway’s term expired in the summer of 1955 he was not reappointed. Instead, Eisenhower turned to Maxwell Taylor, with equally disappointing results. Taylor, a gifted linguist who had commanded the 101st Airborne in World War II and later Eighth Army in Korea, was considered a serious military thinker and an officer of keen intellect. Before sending Taylor’s name to the Senate, Eisenhower extracted from him a firm commitment to support the New Look and the nuclear strategy upon which it was based. “Loyalty in spirit as well as in letter is necessary,” he told Taylor.31

Like Ridgway, Taylor was soon off the reservation, arguing that the United States should abandon massive retaliation and the New Look in favor of what he called Flexible Response. Much to Eisenhower’s consternation, Taylor argued that a future war between the United States and the Soviet Union could be fought with conventional weapons. “That’s fatuous,” Eisenhower told Radford and Wilson. In Ike’s view, any war with Russia would be a nuclear war and in all probability that was why there was not going to be one. When Taylor persisted and suggested that the next war would be a limited one similar to Korea, Eisenhower rejected the idea. “Anything of Korean proportions would be one for the use of atomics,” said the president.32

Taylor served as Army chief of staff for four years. After stepping down in 1959, he continued to press the doctrine of Flexible Response.33 Academic circles joined the debate. Henry Kissinger established his reputation as a foreign policy expert with the publication of Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy in 1957—an unrelenting critique of Eisenhower’s New Look strategy.34 In the partisan days of the late 1950s, the Democrats adopted the concept of Flexible Response. John Kennedy anchored his campaign for president on a pledge to jettison the doctrine of massive retaliation. When he was elected, Kennedy undertook an accelerated program to enhance America’s conventional war capabilities. Maxwell Taylor was recalled from retirement to advise the president (and was later appointed chairman of the Joint Chiefs), and Army ground forces, particularly special forces, enjoyed a renewed emphasis.

Critics of the Kennedy-Johnson administration and of the subsequent U.S. involvement in Vietnam often fault Kennedy’s revival of America’s limited war capability. By having the troops available to intervene incrementally, it was easier for the president to intervene incrementally. As Secretary of State Madeleine Albright put it (in a different context), “What’s the point of having this superb military if we can’t use it?”35 That was the antithesis of Eisenhower’s position. For Ike, war was not a policy alternative. The purpose of military power was to avoid war, not fight one. Soldiers were not paper cutouts, and combat was not a board game.

Eisenhower’s emphasis on the New Look and nuclear weapons preserved the peace during the Cold War. But it spawned a variety of side effects, some benign and beneficial, others downright pernicious. Among the pernicious was the arms race that led to the development of thermonuclear weapons, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and the spiral in defense spending that Ike had hoped to avoid. The possibility of mutual assured annihilation scarcely made for restful sleeping. On the other hand, Eisenhower’s emphasis on nuclear technology fostered significant scientific and educational advances. Research and development became an integral part of the federal budget. Under Ike, the government funded not only applied research, but generously supported pure research in a variety of scientific disciplines. And to do so, Eisenhower often had to beat down the opposition of Charles Wilson and George Humphrey. “Between the year I entered office and the year I left,” wrote Ike, “the federal appropriations for medical research at the National Institutes of Health multiplied nearly ten times, going from $59 million to $560 million [$4.1 billion currently].”36

After the Soviets successfully launched the world’s first man-made satellite (Sputnik) in 1957, Eisenhower created the position of a full-time science adviser to the president, and appointed Dr. James Killian, the president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to the post. Under Killian’s direction, the White House established the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC), which provided Eisenhower a direct avenue for independent advice from the nation’s scientific community. Beginning in 1955, Eisenhower had pressed Congress to provide federal aid to the states for school construction—an unprecedented breakthrough in the relationship between the federal government and the states. The legislation lay dormant for two years on Capitol Hill, but in the aftermath of the Sputnik program, Congress enacted the National Defense Education Act of 1958, providing significant federal aid to education, particularly in the funding of graduate fellowships and improved public school instruction in science, mathematics, and foreign languages. The act followed closely Eisenhower’s recommendations in his message to Congress in late January 1957.37 Ike sold the measure to a reluctant Congress as an emergency measure in the face of Soviet scientific achievements, and the breakthrough in federal funding for education has changed the face of the American educational system.

The Republicans lost control of both the House and the Senate in 1954. In the midterm elections, the Democrats picked up twenty-one House seats and one in the Senate. That gave the Democrats a comfortable (232–203) majority in the House, and a narrow two-vote margin in the Senate with Wayne Morse of Oregon, still an independent, now voting with the Democrats.38 For Eisenhower, who would face Democratic congressional majorities for his remaining six years in office, it was a blessing in disguise. The Democrats supported Ike down the line in foreign affairs, had little interest in returning to the era of Calvin Coolidge domestically, and were not clamoring to investigate the executive branch.

In the House, Sam Rayburn took up the reins once more as Speaker, and Lyndon Johnson became Senate majority leader. Rayburn, a bachelor from Bonham, Texas, was a man of few words. But he ruled the House with a discipline rarely seen since the days of “Czar” Joseph Cannon.d He had first been elected Speaker in 1940 following the death of William Bankhead, and was the undisputed leader of House Democrats. In the Senate, Lyndon Johnson, at forty-six, became the youngest majority leader in Senate history, and as Robert Caro explains, was soon the Master of the Senate.39 With Eisenhower in the White House, Sam Rayburn as Speaker, and Lyndon Johnson as majority leader, the country was in the hands of skilled professionals. Ike, LBJ, and “Mr. Sam” did not trust one another completely and they did not see eye to eye on every issue, but they understood one another and had no difficulty working together. Eisenhower continued to meet regularly with the Republican leadership. But his weekly sessions with Rayburn and Johnson, usually in the evening over drinks, were far more productive.40

For Johnson and Rayburn, it was shrewd politics to cooperate with Ike. Eisenhower was wildly popular in the country, and his foreign policy was essentially a recognition of America’s new role in world affairs. By supporting a Republican president against the Old Guard of his own party, the Democrats hoped to share Ike’s popularity. “Eisenhower was so popular,” Johnson explained, “whoever was supporting him would be on the popular side.”41

For Rayburn, it was personal as well. Eisenhower had been born in Denison, Texas, which was in Mr. Sam’s district. Rayburn had known Ike for years, and he liked him. “He was a wonderful baby,” the Speaker would say with a grin.42 Rayburn not only admired Eisenhower’s wartime leadership, but appreciated his truthfulness whenever he had testified before Congress. The Speaker admired truthfulness. He also respected Eisenhower’s judgment on national security. “I told President Eisenhower … that he should know more about what it took to defend this country than practically anyone and that if he would send up a budget for the amount he thought was necessary to put the country in a position to defend ourselves against attack, I would promise to deliver 95 percent of the Democratic votes in the House.”43 On domestic issues, Rayburn said the Democrats would not oppose just for the sake of opposing. “Any jackass can kick a barn down. But it takes a good carpenter to build one.”44

Eisenhower, for his part, had often found the Republican leadership testy. Taft had been difficult, and William Knowland was but a slight improvement. In the House, Speaker (later minority leader) Joe Martin and party whip Charles Halleck were scarcely on speaking terms. The GOP majority in the Eighty-third Congress seemed less interested in grappling with the problems of the day than in repudiating the work of Truman and Roosevelt. In the Senate, conservative Republicans had introduced no less than 107 constitutional amendments designed to repeal the New Deal. Several sought to annul the decision at Appomattox by asserting the supremacy of the states over the federal government, while one would have abolished the separation of church and state by inserting the following words in the Constitution: “This nation devoutly recognizes the authority and law of Jesus Christ, Savior and Ruler of Nations through whom are bestowed the blessings of Almighty God.”45 Later in his presidency, Eisenhower found himself so frustrated with the Republican leadership in Congress that he told his secretary Ann Whitman, “I don’t know why anyone should be a member of the Republican Party.”46

With Rayburn and Johnson in charge, Ike’s relations with the Hill were much easier. “Speaker Rayburn and I had long maintained friendly contact,” Eisenhower recalled. “For many years prior to my inauguration he had called me ‘Captain Ike.’ ”47 Eisenhower was also on friendly terms with Johnson, and kept a vigil on LBJ’s health. Whenever Johnson was in the hospital, Ike was sure to be at his bedside. “I don’t see any reason why these people shouldn’t be my friends,” Eisenhower once told an inquiring reporter. “They have been my friends in the past.”48

Two of the most significant public works projects in American history—the interstate highway system and the St. Lawrence Seaway—are products of the Eisenhower years. The St. Lawrence Seaway, which opened the Great Lakes to ocean traffic, had been on the drawing board for many years, but it was Eisenhower who got behind it and marshaled the necessary votes to push it through Congress. From the time of Theodore Roosevelt, American presidents had advocated building the seaway, but had been thwarted by the powerful lobbying efforts mounted by American railroads, East and Gulf coast port authorities, coal mine operators in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and the United Mine Workers, led by the truculent John L. Lewis, all of whom believed they would suffer if the seaway were built. Eisenhower, who believed the project was essential for national security, and who feared the Canadians would go ahead regardless of American participation, stepped out in front of the effort. “It was the only major issue on which my brother and I ever disagreed,” said Milton Eisenhower, then president of Penn State.49

With Ike’s vigorous backing, the measure was passed by the Senate in January 1954, and by the House in May. The vote crossed party lines. In the Senate, a bipartisan coalition of twenty-five Democrats and twenty-five Republicans voted in favor. In the House, the vote was 230–158, with each party also divided. Without Eisenhower’s support, the measure would never have been reported out of committee. Ike signed the bill into law on May 13, 1954, and the St. Lawrence Seaway, linking the Gulf of St. Lawrence with Lake Superior, became a reality. “This marks the legislative culmination of an effort that has taken 30 years,” said the president.50 On June 26, 1959, the seaway was officially opened by Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II with a short cruise aboard the royal yacht Britannia. Since its completion, the seaway has averaged fifty million metric tons of shipping annually, and provides an easy means for the bulk shipping of American grains and minerals from the Midwest to ports abroad.e

Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II at the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in Montreal, June 26, 1959. (illustration credit 23.3)

Eisenhower is personally responsible for the interstate highway system—the largest public works project ever attempted. In the aftermath of the Korean War, defense spending slowed and the nation’s economy headed south. The danger signs were evident as early as February 1954. At a cabinet meeting on February 5, Eisenhower stressed the need to develop a public works program so that if needed it could be put into effect immediately. “If we don’t move rapidly, we could be in serious trouble,” said the president.51

Eisenhower favored a highway program. In 1919, Ike had been one of six officers to lead the Army’s first transcontinental motor convoy across largely unpaved roads and makeshift bridges from Washington to San Francisco, and he understood from firsthand experience the need for a network of national highways. During the war, Eisenhower witnessed the effectiveness of the German autobahns.52

By the summer of 1954 it was clear that an economic crisis was at hand. Unemployment rose, and a recession seemed just around the corner. Needing to act, and to act quickly, Eisenhower summoned his old friend Lucius Clay to Washington—the only time during his eight years in the White House that Ike turned to Clay. “We had lunch,” Clay recalled, “and he asked me if I would head a committee to recommend what should be done. He felt that a highway program was very important. That was the genesis of the President’s Advisory Committee on a National Highway Program.”

Following his lunch with Eisenhower, Clay put together a five-man high-level committee stacked to recommend a national highway system: Stephen Bechtel of the Bechtel Corporation; William Roberts, head of Allis-Chalmers; Samuel Sloan Colt, president of Bankers Trust; and Dave Beck, president of the Teamsters Union. All had a vested interest. “That’s why I picked them,” said Clay. “They knew what the highway system was all about.”

It was evident we needed better highways. We needed them for safety, to accommodate more automobiles. We needed them for defense purposes, if that should ever be necessary. And we needed them for the economy. Not just as a public works measure, but for future growth. It was also evident that these new and better highways should be so connected to provide routes from somewhere to somewhere. Therefore, the interstate concept. This idea was already well developed within the old Bureau of Public Roads, and we built on that.53

The Clay committee rendered its report to Eisenhower on January 12, 1955. It recommended an expenditure of $101 billion ($823 billion currently) over ten years, and forty-one thousand miles of divided highways linking all U.S. cities with a population of more than fifty thousand. Not only was it the largest public works project ever proposed, but when completed it would provide the United States with a highway net superior to that in any country, including Germany. Eisenhower, who had followed the work of the Clay committee closely, signed on immediately—with one exception. Clay had recommended the system be funded initially by a $25 billion federal bond issue at 3 percent interest. Ike said he preferred a toll road system. Clay demurred. Toll roads, he told Eisenhower, would work in the heavily populated sections of the East and West coasts, but were not feasible in the remainder of the country. “We have taken the position that a toll road is luxury transportation and is all right in sections of the country where the public have alternative roads to travel. [But] where the interstate highway system is the only road we do not think it should be tolled.”54 Eisenhower accepted Clay’s explanation, and on February 22, 1955, sent the National Highway Program to Congress. “Our unity as a nation is sustained by free communication of thought and by easy transportation of people and goods,” said the president. “The nation’s highway system is a gigantic enterprise. One in every seven Americans gains his livelihood and supports his family out of it. But, in large part, the network is inadequate for the nation’s growing needs.” Eisenhower asked for speedy approval of the measure.55

The Federal-Aid Highway Act sailed through the Senate in May, but lost in the House 123–292. The Democratic majority objected to the bond issue and wanted the money for the interstates to come directly from the Treasury. When the second session of the Eighty-fourth Congress convened in January, a compromise had been reached. Rather than paying for the interstates through a bond issue, or by direct federal expenditures, the federal government would levy a gasoline tax of 4¢ per gallon, the money designated for a highway trust fund. Eisenhower was satisfied the measure would not be a charge on the Treasury, and the Democrats were content with user taxes. The revised measure passed both houses easily, and Eisenhower signed the bill into law on June 29, 1956. Today, the interstate highway system, officially the “Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways,” stretches 46,876 miles, and contains 55,512 bridges and 14,756 interchanges. The Highway Trust Fund, funded originally by a 4¢ per gallon levy, is now supported by the federal fuel tax of 18.4¢ per gallon, of which 2.86¢ is earmarked for mass transit. Total revenue from the tax exceeds $40 billion annually.

Eisenhower was a fiscal conservative. He believed in a balanced budget, worked hard to attain it, and eventually succeeded.f But he was not a movement ideologue and had no interest in dismantling the national government. Federal action, he once said, was sometimes required to “floor over the pit of personal disaster in our complex modern society.”56 The interstate highway system and the St. Lawrence Seaway are enduring examples of Eisenhower’s belief in a positive role for government. Less well known is his expansion of Social Security in 1954 to provide coverage for an additional ten million self-employed farmers, doctors, lawyers, dentists, and others; his decision to increase benefits 16 percent for those already enrolled; his raising the minimum wage by a third (from 75¢ to $1 an hour),g his decision to provide the funds for Salk polio vaccine for the nation’s underprivileged children, and his establishment of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. When Ike appointed Oveta Culp Hobby as the first secretary of HEW, he told her he wanted to establish a national system of health care similar to what everyone received in the Army.57 FDR had made a similar suggestion to Frances Perkins when the Social Security system was on the drawing board in 1935. In both instances the presidential requests fell by the wayside in the day-to-day press of business.h

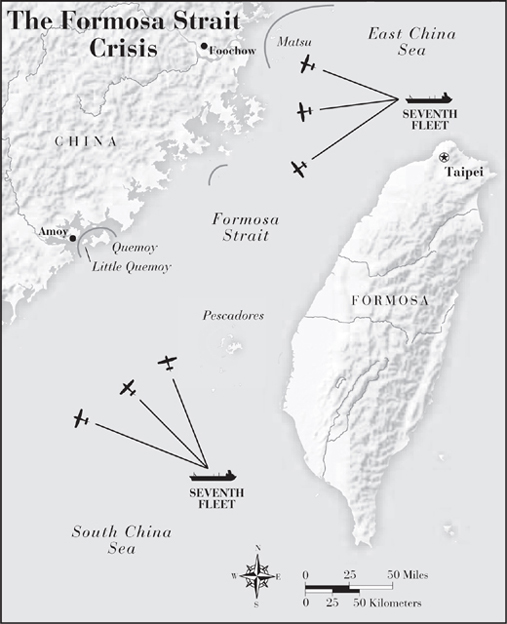

During Eisenhower’s third year in office the nation found itself on the brink of war. Again, it was in the Far East, and again with China. In 1949, when Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces had been driven from the Chinese mainland to Formosa (Taiwan), scattered Nationalist garrisons remained on three offshore island groups: the Tachens, Quemoy, and Matsu. Formosa, roughly 150 miles off the China coast, had been liberated from the Japanese in 1945 by the United States and was an integral part of the American defense perimeter in the Pacific. But the three island groups, much closer to the mainland, were historically a part of China itself and had been under the control of the central government. The Tachens, far to the north, were occupied by fifteen thousand Nationalist troops. The Matsu chain, some nineteen rocky outcroppings less than ten miles from the mainland port of Fuchou, were held by nine thousand of Chiang’s soldiers, and the Quemoy group, roughly sixty square miles in area, blocked the port of Xiamen, which was less than two miles away. The Quemoy garrison numbered fifty thousand or so, and was face-to-face with Chinese Communist forces across a few thousand yards of water.

From 1949 to 1954 an uneasy truce had prevailed as the Chinese Communist government consolidated its position on the mainland and Chiang did the same on Formosa. But on September 3, 1954, Communist forces on the mainland launched a sustained artillery barrage against Quemoy, and sporadic shelling continued throughout the fall. “The shelling did not come as a complete surprise,” wrote Eisenhower. Chiang Kai-shek had been threatening to attack the mainland “in the not distant future,” and Chou En-lai had called for the “liberation of Formosa” in reply. It was almost inevitable that the war of words would escalate. An invasion of Quemoy appeared imminent.58

In Washington, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Ridgway excepted) urged that the United States commit itself to defending the offshore islands and launch air strikes, with tactical nuclear weapons if necessary, against the mainland to break up Communist forces assembling there. Eisenhower said no. “We are not talking now about a brush-fire war,” Ike told the chiefs. “We’re talking about going to the threshold of World War III. If we attack China, we’re not going to impose limits on our military actions, as in Korea. [And] if we get into a general war, the logical enemy is Russia, not China, and we’ll have to strike there.”59

Confronted with the possibility of total nuclear war, the Joint Chiefs cooled their ardor. But on Capitol Hill the “China Lobby” stepped up its demands for the United States to take action on Chiang’s behalf. Senator William Knowland, the Republican leader, went so far as to urge preventive war against China and the Soviet Union. “Do you suppose that Knowland would actually carry his thesis to the logical conclusion of presenting a resolution to the Congress aiming at the initiation of such a conflict?” Eisenhower wrote General Gruenther at NATO. “I don’t believe this for a second.” Knowland’s only policy, Ike told Gruenther, was “to develop high blood pressure whenever he says ‘Red China.’ ”60

Eisenhower steered a difficult course. On the one hand, he was determined to defend Formosa, and on the other he was equally determined to avoid war with China. The offshore islands were not worth fighting for, but he could not abandon them. Chiang was unwilling to withdraw because of the adverse effect on his Army’s morale, but if the Communists wished to take them they could easily do so. Ike was a poker player. It was time to bluff without revealing his hand. China must be made wary of possible U.S. intervention, and Chiang must be restrained from launching any attack against the mainland. “The hard way is to have the courage to be patient,” Eisenhower told Senate Republicans.61

On January 18, 1955, Communist forces landed on the island of Ichiang, seven miles from the Tachen group, and quickly overwhelmed the defenders. A move on the Tachens—which were two hundred miles from Formosa—appeared inevitable. Eisenhower responded with a two-step. He asked Congress for authorization to defend Formosa and the nearby Pescadores, but suggested that the Tachens be evacuated. Chiang would get a congressional guarantee of American support, but to do so he must relinquish the distant island group. The fate of Quemoy and Matsu was left ambiguous. “I do not suggest that the United States enlarge its defensive obligations beyond Formosa and the Pescadores,” Eisenhower told Congress, “but the danger of armed attack directed against that area compels us to take into account closely related localities which, under current conditions, might determine the failure or success of such an attack.”62

Chiang, who recognized that the Tachens could not be defended without direct American intervention, acquiesced and was rewarded with a mutual defense treaty in which the United States undertook a solemn treaty obligation to defend Formosa and the Pescadores. But the Joint Chiefs initially resisted Ike’s strategy. Admiral Carney, the chief of naval operations, argued that because of harbor obstructions evacuating the islands would be more difficult for the Navy than defending them. Eisenhower, with amphibious landings in North Africa, Sicily, and Normandy under his belt, overruled Carney’s objection. Admiral Felix Stump, the commander in chief of the Pacific fleet, was ordered to evacuate Nationalist forces from the Tachens, as well as all civilians who wished to leave. Stump was told not to initiate hostilities, but if fired upon he could return fire. One week later the Seventh Fleet successfully evacuated almost fifteen thousand of Chiang’s troops and twenty thousand civilians from the Tachens without incident.

On January 29, 1955, the Senate adopted the Formosa resolution Eisenhower had requested, authorizing the president “to employ the armed forces of the United States as he deems necessary for the specific purpose of securing and protecting Formosa and the Pescadores against armed attack.” The resolution also gave Ike the discretion to include “such related positions and territories of that area now in friendly hands … as he judges to be required or appropriate”—a veiled reference to Quemoy and Matsu without including them explicitly. The vote was 83–3 in the Senate, with Democratic senator Walter George of Georgia, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, introducing the resolution on the administration’s behalf. In the House, the vote was a lopsided 410–3. In what may seem a curious twist in light of recent history, the opposition in the Senate was mounted by liberal Democrats who argued that the president’s inherent powers as commander in chief gave him adequate authority to take action and that the resolution was unnecessary.63

With the passage of the Formosa Resolution, Eisenhower had what he wanted. The Chinese Communists were put on notice that the United States would defend Formosa, and the possibility that it might also protect Quemoy and Matsu was left to the president’s discretion. In another quid pro quo, Chiang agreed not to attack the mainland without U.S. approval. The situation played out during the spring of 1955. Eisenhower’s stance was sufficiently ambiguous to keep the Chinese Communists in check, and the danger that Chiang would upset the apple cart had been eliminated. It was a time of watchful waiting. “Sometimes,” Ike told a meeting of legislative leaders on February 16, “I wish those damned little offshore islands would sink.”64

While both sides held back militarily, the rhetoric escalated. Before his news conference on March 23, press secretary James Hagerty told Eisenhower, “Some of the people in the State Department say that the Formosa Strait situation is so delicate that no matter what question you get on it, you shouldn’t say anything at all.”

“Don’t worry, Jim,” Ike replied. “If that question comes up, I’ll just confuse them.”65

Ike was true to his word. Halfway through the president’s news conference, Joseph C. Harsch of The Christian Science Monitor asked Eisenhower the question the world was waiting for. “If we got into an issue with the Chinese, say over Matsu and Quemoy, that we wanted to keep limited, do you conceive of using this specific kind of [tactical] atomic weapon in that situation or not?”

Eisenhower’s answer was a masterpiece of obfuscation.

THE PRESIDENT: Well, Mr. Harsch, I must confess I cannot answer that question in advance.

The only thing I know about war are two things: the most changeable factor in war is human nature in its day-by-day manifestation; but the only unchanging factor in war is human nature.

And the next thing is that every war is going to astonish you in the way it occurred, and in the way it is carried out.

So that for a man to predict, particularly if he has the responsibility for making the decision, to predict what he is going to use, how he is going to do it, would I think exhibit his ignorance of war; that is what I believe.

So I think you just have to wait, and that is the kind of prayerful decision that may some day face a President.

We are trying to establish conditions where he doesn’t.66

The Chinese evidently deciphered Ike’s answer and chose to stand pat. But the Joint Chiefs remained restive. At the end of March, Admiral Carney leaked word to the press alleging that the president and his advisers believed an attack on Quemoy and Matsu was imminent. Eisenhower was furious. Carney was rocking the boat. The last thing Ike wanted was talk of war. The next day, at the president’s direction, Hagerty provided his own leak to the White House press corps: “The President did not believe war was upon us.” Carney’s views were “parochial,” said Hagerty, and should not be confused with the facts of the matter.67 i In his diary, Ike wrote, “I believe hostilities are not so imminent as is indicated by the forebodings of a number of my associates. I have so often been through these periods of strain that I have become accustomed to the fact that most of the calamities that we anticipate really never occur.”68 Several days later, Eisenhower told Sam Rayburn that “the tricky business is to determine whether or not an attack on Quemoy and Matsu, if made, is truly a local operation or a preliminary to a major effort against Formosa.”69

Eisenhower’s cool head defused the crisis. The bellicose rhetoric subsided, the war party in Washington pulled in their horns, and the Chinese flashed an all clear. At the first conference of Asian-African nations meeting at Bandung, Indonesia, on April 23, 1955, Chou En-lai declared the Chinese government was “willing to sit down with the United States government to discuss the question of relaxing tension in the Far East.”70 Eisenhower responded positively. If the Chinese Communists wanted to talk about a cease-fire, the president told his news conference on April 27, “we would be glad to meet with them and talk with them.”71

The shelling of Quemoy and Matsu eased off, and by mid-May it stopped completely. Talks by American and Chinese representatives commenced on August 1, and shortly afterward, the last American prisoners held by the Chinese from the Korean War were quietly released.72

Writing about the offshore island crisis years later, Eisenhower summed up the advice he had received. Former British prime minister Clement Attlee had urged him to liquidate Chiang Kai-shek. Anthony Eden advocated neutralizing Quemoy and Matsu. Various Democratic senators had urged the islands be abandoned. Admiral Radford and Senator Knowland wanted to defend the Tachens, blockade the Chinese coast, and bomb the mainland, while Syngman Rhee wanted to launch a “holy war of liberation.”73 Eisenhower charted his own course and emerged from the crisis with almost total victory. War with China had been avoided, Quemoy and Matsu remained in Nationalist hands, and the defense of Formosa was secure.

Congress had given Eisenhower what amounted to a blank check when it adopted the Formosa Resolution, and Ike had delivered. Without excessive saber rattling, he had so confused the Chinese as to whether the United States would use atomic weapons to defend Quemoy and Matsu that they decided not to risk it. Eisenhower’s ambiguous public remarks had restored calm to a situation that could easily have triggered World War III. He did not have to use the bomb, he kept the peace, and with the exception of evacuating the Tachens, restored the status quo.

As more than one observer has written, Eisenhower’s handling of the Quemoy-Matsu crisis was a tour de force. It was one of the great victories of his career, and the key had been his coolness under pressure—his calculated use of ambiguity and deception. Eisenhower was comfortable wrestling with uncertainty. “The beauty of Eisenhower’s policy,” wrote historian Robert Divine, “is that to this day no one can be sure whether or not he would have responded militarily to an invasion of the offshore islands, and whether he would have used nuclear weapons.”74 The chances are that Ike himself did not know. As he told Sam Rayburn, the tricky part was to determine what the Chinese were up to. It was a two-way street. The Chinese kept Eisenhower guessing, just as he kept them off balance. One thing stands out: As on D-Day and at Dien Bien Phu, Eisenhower kept the final decision in his own hands.j

a Mamie’s Bolivia regulars included Mrs. Everett Hughes, Mrs. Walton Walker, and Mrs. Harry Butcher, all former neighbors from the Wyoming or the Wardman Park, as well as Mrs. George Allen and Mrs. Howard Snyder, the wife of Ike’s personal physician. J. B. West and Mary Lynn Kotz, Upstairs at the White House: My Life with the First Ladies 161 (New York: Coward, McCann, and Geoghegan, 1973).

b ”Shangri-La” is a fictional place described in the 1933 novel Lost Horizon by James Hilton—a mythical Himalayan utopia isolated from the outside world. The novel was made into a film of the same name by Frank Capra in 1937 and starred Ronald Colman. FDR was fond both of the novel and the film and named the presidential retreat accordingly. In 1942, when newsmen asked him where the bombers that bombed Tokyo had come from, the president mirthfully said, “Shangri-La,” a reference to the Himalayan utopia, not the presidential retreat. James Hilton, Lost Horizon (London: Macmillan, 1933). Also see Charles Allen, The Search for Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History (London: Little, Brown, 1999); Presidential press conference, April 21, 1942, 19 Complete Presidential Press Conferences of Franklin D. Roosevelt 291–92 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972).

c Alton Jones was killed in an air accident in 1962. He bequeathed his farms to the United States government as an addition to the Gettysburg National Military Park, subject to Ike’s continued use of the property until his death. On November 27, 1967, Eisenhower and Mamie gave their farm to the government as well, with the provision that Mamie could stay until her death. The farm is now maintained by the National Park Service and is open to the public.

d As a young fellow growing up in Washington, D.C., I frequently held summer jobs on Capitol Hill. Often when work was over, I would go into the visitor’s gallery overlooking the House chamber and watch the proceedings. I still remember Speaker Rayburn’s command of those proceedings. On occasion he would ask for the yeas and nays. Sometimes the nays would be shouted far louder than the ayes. That did not bother Mr. Sam. The gavel would come down and Rayburn would announce that the ayes had it (or whatever outcome he desired). He was rarely challenged.

e The St. Lawrence Seaway runs from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Duluth, Minnesota, on the western shore of Lake Superior, a total of 2,275 miles. More than two thousand ships traverse the seaway annually, with the trip from Lake Superior to the Atlantic averaging eight to ten days.

Critics of the seaway were not entirely wrong as to its adverse effect on eastern cities. Buffalo, New York, which had been the eastern terminus for Great Lakes shipping before the seaway, was the fifteenth largest city in the United States in 1950. In 2010, it ranks forty-fifth and its population has declined by half.

f The budget Eisenhower inherited in 1953 showed a deficit of $6.5 billion. That was reduced to $1.2 billion in 1954, and by 1956 the federal budget was $3.9 billion in the black. The arms race plunged the budget back into deficit in 1958, but in 1960, Ike’s last year in office, the government ran a surplus of $301 million. Financial Management Service, U.S. Department of the Treasury.

g A one-dollar-an-hour minimum wage does not seem like much today. But a dollar in 1955, adjusted for inflation, equals $8.15 currently. Today’s minimum wage is only $7.25. In comparative terms, that is 90¢ less than in Ike’s day.

h In 1954, the Eisenhower administration introduced a reinsurance plan to backstop private insurance companies against “abnormal loss” if they expanded their coverage to individuals not adequately covered by health insurance. The reinsurance plan, in Ike’s view, was a “middle way” between government and private insurance. Despite vigorous administration backing, the plan was opposed by the American Medical Association as the opening wedge to “socialized medicine.” On July 13, 1954, it lost in the House of Representatives, 134–238, with 75 Republicans voting no. “The people that voted against this bill just don’t understand what are the facts of American life,” Eisenhower told his press conference the following day. Public Papers, 1954 633.

i At his press conference on March 30, 1955, Eisenhower was asked whether Admiral Carney would be reprimanded for his remarks. “Not by me,” the president replied—a classic Eisenhower response. Carney’s reprimand came from Defense Secretary Wilson, who immediately issued an order directing all military personnel to henceforth submit for clearance all speeches, press releases, and “other information” intended for publication. When Carney’s term as CNO expired that summer, he was replaced by Admiral Arleigh “Thirty-one Knot” Burke. (During World War II, Burke mistakenly led his destroyer squadron into a Japanese minefield. Admiral Halsey radioed to ask Burke what he was doing in a Japanese minefield. “Thirty-one knots,” Burke replied. Eisenhower advanced Burke over the heads of ninety admirals more senior.) Press conference, March 30, 1955, Public Papers, 1955 374.

j In a lengthy letter to General Gruenther, Eisenhower attempted to explain his thought process on the Formosa question.

We must make a distinction (this is a difficult one) between an attack that has only as its objective the capture of an offshore island and one that is primarily a preliminary movement to an all-out attack on Formosa.… More and more I find myself, in this type of situation—and perhaps it is because of my advancing years—tending to strip each problem down to its simplest possible form. Having gotten the issue well defined in my mind, I try in the next step to determine what answer would best serve the long term advantage and welfare of the United States and the free world. I then consider the immediate problem and what solution we can get that will best conform to the long term interests of the country and at the same time can command a sufficient approval in this country so as to secure the necessary Congressional action.

When I get a problem solved on this rough basis, I merely stick to the essential answer and let associates [Dulles? Nixon?] have a field day on words and terminology.…

Whatever is now to happen, I know that nothing could be worse than global war.

DDE to Gruenther, February 1, 1955, The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower, vol. 16, The Presidency 1539, cited subsequently as 16 The Presidency. (Eisenhower’s emphasis.)