Although there are many muscles located on and within the head and neck, the scope of this book will be confined to those soft tissue structures that are known to become tight or restricted or can be implicated in conditions that cause discomfort through dysfunctional movement and can be treated with STR. These will include muscles and other soft tissue associated with the temporomandibular joint and the joints of the cervical spine.

The TMJ is the articulation between the condyle of the mandible and the temporal bone. There is a fibrous, saddle-shaped meniscus separating the condyle and the temporal bone: it is attached to posterior soft tissues that allow the condyle to move forwards.

Figure 1.1: The TMJ and the skull.

Figure 1.2: The TMJ.

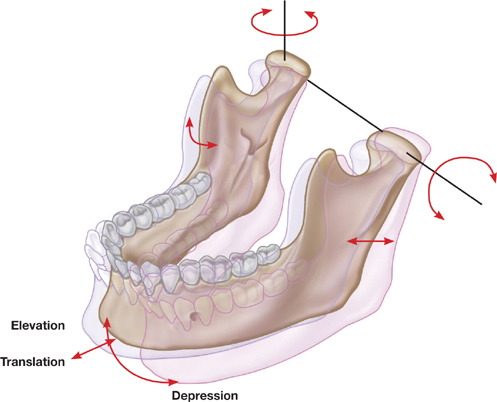

Two key motions occur at the joint when the mouth opens. The first is rotation around an axis that passes through the condylar heads. The second is translation in which the condyle and meniscus both move anteriorly beneath the articular eminence. Mastication requires a more complex movement of the mandible involving depression with protrusion, lateral deviation, elevation with retrusion and medial deviation back to the start position.

Figure 1.3: TMJ movement.

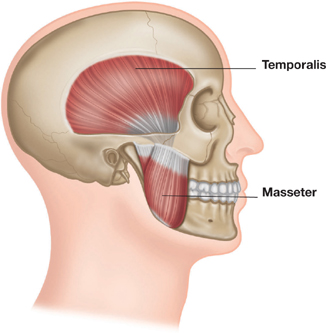

Figure 1.4: Muscles of the TMJ.

In this book the neck is defined as the cervical spine and those muscles involved in osteokinematic movements as observed by the position of the head with respect to the body and those arthrokinematic movements at joints which enable the gross movements to occur.

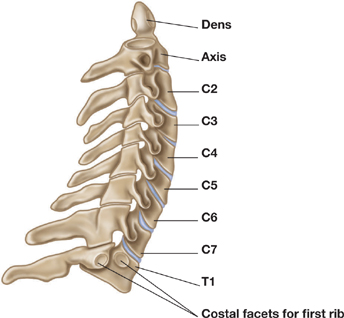

Figure 1.5: Cervical spine and facets.

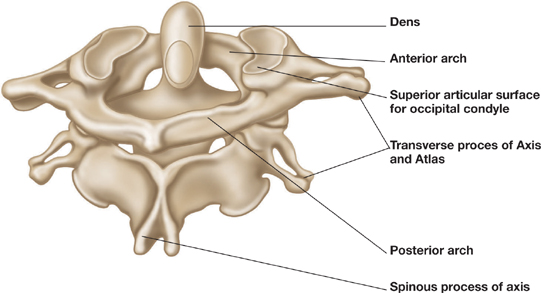

The articulation between the skull (occipital bone) and the first cervical vertebra is the atlanto-occipital joint; the next articulation, between the first and second vertebrae, is the atlanto-axial joint. Neither of these articulations has a disc. However, the rest of the cervical vertebrae are connected by vertebral discs and facet joints. In addition to these key articulations, C3 to C7 vertebrae also have structures called joints of Luschka and uncinate processes. The way in which these contribute to cervical neck motion is still unclear. It is these various articulations that determine much of the available motion of the neck.

Figure 1.6: Atlanto-occipital joint.

Figure 1.7: Atlanto-axial joint.

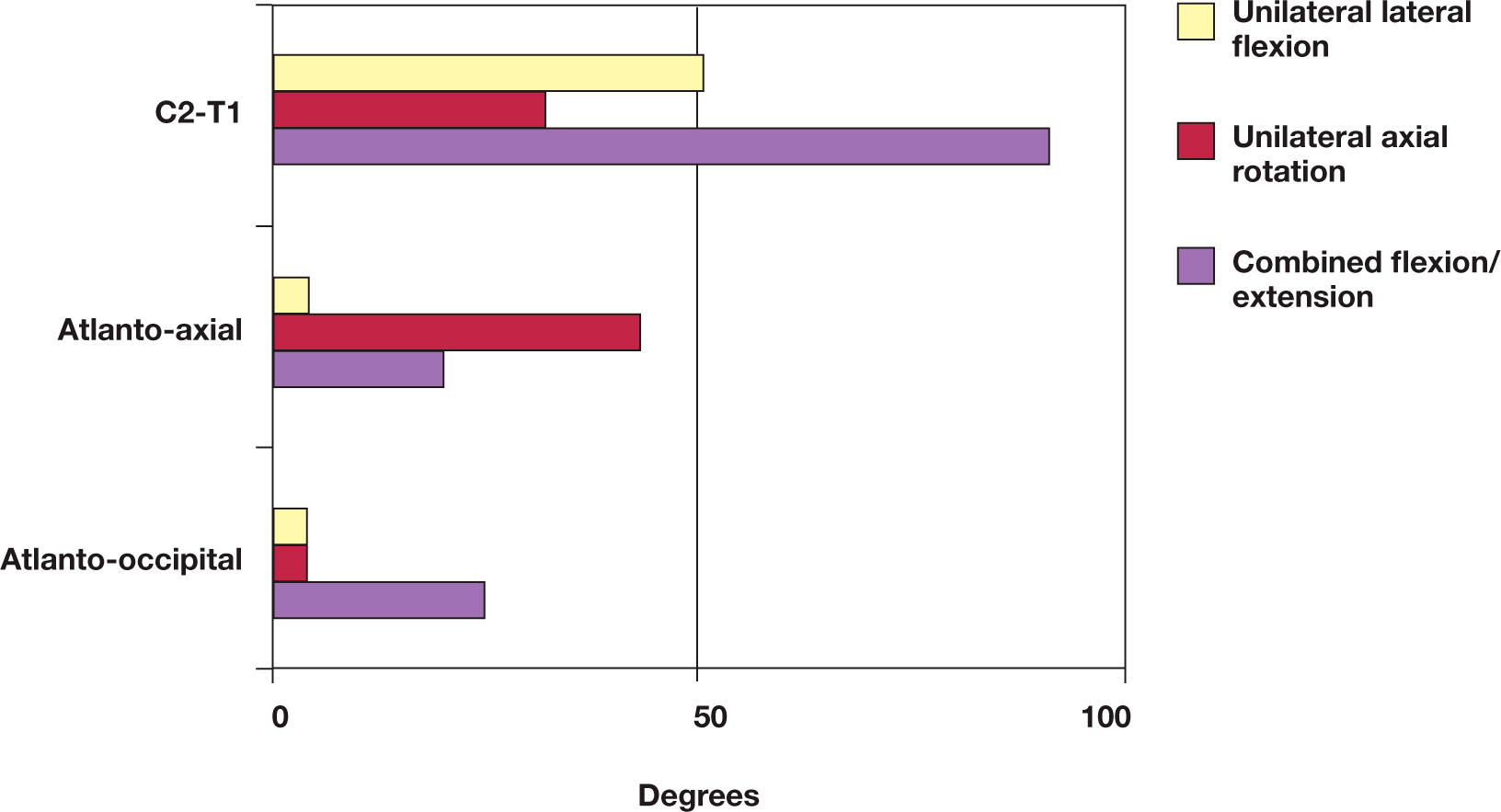

The structure of the atlanto-occipital joint provides a high proportion of the flexion and extension movement seen as nodding of the head, whilst the atlanto-axial joint provides almost 50% of rotational movement. The remaining motion of the neck comes from each of the lower cervical joints contributing in part to the full range.

Figure 1.8: Cervical spine segmental range of motion.

The design of the cervical spine means that motion in one plane does not happen without motion in another; this ‘coupled motion’ varies as we move down the cervical spine. At the atlanto-occipital joint the occipital condyles translate downwards and backwards as flexion of the head takes place. The atlanto-axial joint does not appear to exhibit defined coupled motion but is responsible for the first 35 to 45 degrees of head rotation before the lower neck moves.

From C2 to C7 (T1) any lateral (side) flexion is accompanied by contralateral rotation (as measured by the spinous process movement). It is now believed that the facet joints and the joints of Luschka are the prime factors in creating coupled motion. Some authors also suggest that extension or flexion motion occurs with lateral and rotational motion as well, although the exact nature of this movement is still unclear. In the lower sections of the cervical spine, flexion is thought to be accompanied by anterior translation and anterior rotation.

Figure 1.9: Coupled motion C2 to C7.

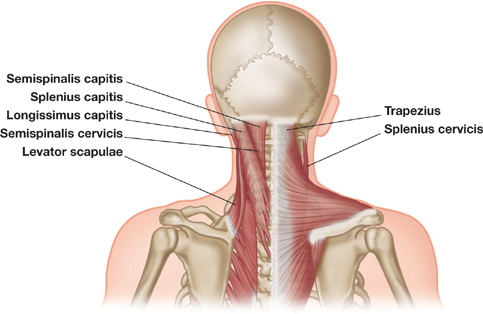

Figure 1.10: Muscles of the neck.

| Muscle | Effect of restriction |

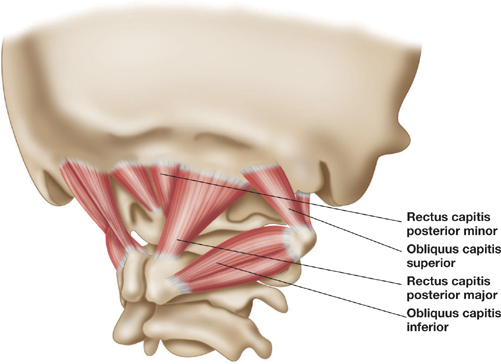

Suboccipital • Rectus capitis posterior minor • Rectus capitis posterior major • Superior oblique • Inferior oblique |

Limited studies exist on the effects of tightness in these muscles, although connections to dura are found in rectus capitis posterior minor, which is associated with headaches. There is also a suggestion that tightness may affect positioning of head, increasing upper cervical extension. |

| Semispinalis capitis | Reduced flexion of head and cervical spine. Entrapment of greater occipital nerve. |

| Splenius capitis Splenius cervicis | Reduced flexion of head and cervical spine. Limited studies exist on these muscles. |

| Longissimus capitis | Increased lateral flexion of head on neck when observed in frontal plane, and posterior rotation of cervical spine. |

| Levator scapulae | Pain in medial scapula and neck. Increased ipsilateral neck flexion and/or raised scapula. |

| Trapezius | Reduced head and cervical spine flexion and ipsilateral rotation of head. Head pain is thought to be linked to trigger points in tight upper fibres. |

| Sternocleidomastoid | Torticollis, both spasmodic and congenital. Head-forward posture. Increased extension of upper cervical spine. |

| Scalenes | Sensation changes in arms and hands as the brachial plexus is compressed. Reduced rotation and increased lateral flexion of cervical spine. |

Road cycling requires long periods of head and neck extension. This will often lead to tight sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles, and eventually the head and neck extensor muscles will be affected, causing their own problems, including upper back pain and headaches. Not only will this have an impact on cycling performance but it can increase the danger factor, as the ability to rotate the head and neck to look behind will be impaired.

Archery requires the head to be rotated and held at almost full rotation. This is accompanied in many cases by active lateral flexion to line up the sighting eye. This position requires virtually all of the neck muscles to contract and shorten on one side. Raising of the shooting arm will also shorten the upper trapezius and the levator scapulae on the opposite site. Potential issues include headaches and upper extremity pain, paresthesias, numbness, weakness, fatigability, swelling and discoloration due to compression of the brachial plexus at the scalenes.

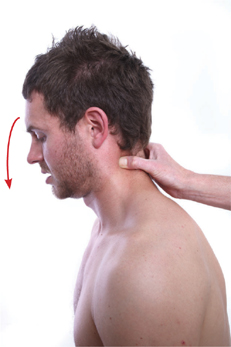

Many people notice neck restrictions for the first time when their ability to rotate their head to look over the shoulder when driving is compromised. This can be caused by tightness in almost any or all of the head and neck muscles but in particular the upper trapezius, scalenes and SCM. However, the coupled motion that occurs throughout the cervical spine can be affected by many of the smaller muscles, and, since almost 50% of rotation occurs at the atlanto-axial joint, restrictions in the muscles of attachment here can also drastically reduce head rotation.

Make a note of the subject’s head and neck position. Check his active ROM: flexion/extension, rotation and side flexion.

Be acutely aware of the structures – nerves, arteries and glands – during STR to the muscles of the neck. Be particularly sensitive in the anterior triangle and lock in carefully, addressing muscle borders where possible. When working on the anterior and medial scalenes, the brachial plexus may be compressed if the muscles are congested: avoid too much pressure and work delicately to minimise irritation of the nerve. If the pulse from the carotid artery is felt while grasping the SCM, release immediately and relocate the lock. It is generally advisable for the massage therapist to perform STR actively in the neck region: this will ensure that the subject is moving within a functionally-capable ROM. If the tissue is particularly fibrous or if the ROM is significantly reduced, resisted STR is beneficial.

1) With the subject’s head in neutral position, gently grasp either side of the SCM; only perform STR on one SCM at a time. Ask him to slowly extend his head. Do the same thing on the other side. If it is difficult to locate the muscle, ask the subject to lift his head off the table and gently grasp the contracting muscle as he places his head back down onto the couch; ask him to extend his head.

2) Ask the subject to move his head into side flexion and gently grasp the SCM on the shortened side. Ask him to side flex his head the other way for a stretch.

3) With the head in neutral position, gently grasp the SCM; ask him to rotate to the same side for a stretch. Perform locks, starting at the insertion towards the mastoid process, in the belly of the muscle, and two separate locks for the sternal point of origin and the clavicular point of origin.

• It will be easier to do active STR to avoid holding the heavy weight of the head and to avoid moving the neck beyond a comfortable appropriate range.

• Use a CTM lock to pick up the borders of the SCM; try moving each side in the opposite direction, prior to initiating the stretch.

• If the SCM is particularly ‘embedded’ or difficult to grasp, try addressing the medial and lateral sides one side at a time, rather than grasping the whole muscle.

1) Support the subject’s head with one hand and gently apply a CTM into the anterior scalenus; apply the lock close to the clavicle and just underneath the lateral border of the SCM, as he inhales. Slowly side flex the neck to the opposite side as he exhales. Apply a lock lateral to this for the medius scalenus.

2) Support the head with one hand and side flex the neck, to shorten the muscle, as the subject inhales. Use two fingers to drop into the posterior scalenus, between the medius scalenus and the levator scapulae; side flex away as he exhales.

• Compression of the brachial plexus can be caused by restriction to the medius and anterior scalenes – the muscles that this network of nerves runs between. STR is an ideal way of releasing the muscles without causing irritation to the nerves.

1) Use a phalange or a thumb reinforced with fingers to lock into the trapezius close to C7. Ask the subject to side flex his head to the opposite side. Re-apply a lock in the belly of the muscle and close to the acromion. Ask him to side flex to the opposite side.

2) Use fingers or a reinforced thumb to lock in close to C7 and ask the subject to slowly side flex his head. This may be easier to do one side at a time while supporting the head on the other side. Apply locks in and away from the ligamentum nuchae; each time ask him to side flex his head.

3) Use a CTM lock on the occiput attachment and ask him to side flex his head.

1) Hook both hands over the top of the anterior fibres of the upper trapezius and use fingers to curl underneath one side at a time in a CTM lock; ask the subject to alternate between side flexion and rotation of the head. Side flex away from the lock and rotate to the same side for a stretch.

2) Sit on the side of the couch and use fingers to curl under the anterior fibres of the trapezius; ask him to rotate his head to the same side or side flex his head to the opposite side.

3) Use an elbow or a knuckle to lock in close to C7; ask the subject to flex his neck forwards or to side flex the head to the opposite side. Lock into the belly of the muscle and close to the acromion.

4) Use a CTM lock on the spine of the scapula and ask him to side flex his neck. (See here for release with scapula movement.)

1) Ensure that the upper fibres of the trapezius are warmed up. With a reinforced thumb, lock deep to the trapezius fibres towards the tendon of origin at the superior angle of the scapula. If the anterior fibres of the trapezius are sufficiently free, use fingers to hook underneath them, towards the anterior surface of the superior angle of the scapula. Ask the subject to side flex his neck to the opposite side, or to flex it. For more lengthening ask him to side flex his neck and from that position ask him to flex his neck.

1) Support the side of the subject’s head with one hand and use a finger reinforced with another one to curl under the trapezius at C4 level; ask him to side flex his neck gently into the hand. Perform another lock and stretch higher up.

1) Lock into the splenius capitis, directly palpable between the SCM and the trapezius, running obliquely to the trapezius, using a finger reinforced with another one. Ask the subject to rotate his head to the opposite side or ask him to tuck his chin in. Use a CTM lock close to the mastoid process.

2) Use a thumb reinforced with fingers to lock deep into the splenius muscles close to C7. Ask the subject to rotate his head to the opposite side.

• The splenius cervicis lies deep to the capitis.

1) Use the olecranon or a knuckle to lock in deep to the trapezius and close to C7; ask the subject to flex his head forwards or to rotate it to the opposite side. Apply a lock away from the lower half of the ligamentum nuchae and away from the upper three thoracic vertebrae.

2) Use fingers to grasp either side of the trapezius in the cervical region and to curl around its lateral border to target the splenius muscles. Ask the subject to flex his neck. Use a reinforced finger to address one side at a time and ask him to side flex his neck.

1) Use the index finger reinforced with the middle finger to lock in close to C7; ask the subject to flex his head forwards. He can also try to rotate his head to the other side for resisted STR, by gently pushing his head into the pillow. Apply locks from the lower half of the ligamentum nuchae and away from the upper three thoracic vertebrae.

2) Use a finger to gently lock into the splenius, directly palpable between the trapezius and the SCM; ask the subject to tuck his chin in.

3) Use a CTM lock to address the attachment at the mastoid process; ask him to tuck his chin in.

1) Use reinforced fingers to apply locks deep to the trapezius and splenius muscles and close to the spinous processes; ask him to flex his neck forwards. He can also try to side flex his neck by pushing his head down into the pillow.

• Locks can be performed from T7 up to C2.

1) Sit or stand at the head of the couch. Use a middle finger reinforced with the index finger to apply a deep pressure into the lamina groove; ask him to tuck his chin in. Apply locks in the cervical region between the transverse and spinous processes.

• Ensure that the more superficial neck muscles of the trapezius, splenius and erector spinae have been loosened up prior to STR in this area.

1) Gently hold the head with both hands and curl fingers underneath the occiput. Slowly lock in deep to the trapezius, splenius capitis and the semispinalis capitis. Ask the subject to slowly tuck his chin in. Slowly lock in away from C1 and lock in away from C2, each time guiding him into a chin tuck.

• If the head feels too heavy to do both sides at the same time, support the head with one hand and let the hand rest on the couch; do one side at a time.

It is useful to palpate both sides at the same time during warm-up STR; this allows for a good comparison to be made of both tissue texture and movement of the jaw on each side. To work more specifically and intraorally, treat one side at a time.

1) Use fingers to lock into the temporalis; ask the subject to open his mouth (depress the mandible). Use a CTM lock to address the tendon of origin at the coronoid process; ask him to open his mouth.

2) Use one finger reinforced with another to lock into the superficial belly of the masseter; ask the subject to open his mouth. The deep belly is palpable from inside the mouth. Use the index finger of each hand to target the muscle from both sides: one locating inside the mouth and the other outside. Ask him to open his mouth.

3) The pterygoids are palpable from both inside and outside of the mouth. Working intraorally provides an effective release. Use the index finger of each hand to target the lateral pterygoid muscle from both sides. Carefully lock in so that the two fingers meet and ask the subject to slowly close his mouth, avoiding any biting of the therapist’s finger! Locate the medial pterygoid in the same way and ask him to open his mouth.