When evaluating the shoulder, the emphasis must always be on the whole shoulder girdle complex and not simply on the ‘shoulder’, or glenohumeral joint. The shoulder girdle comprises the sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints, associated muscles, ligaments and other soft tissue. Its design allows a large ROM, coupled with the requirement of a stable base for muscles to anchor onto. It is a design that enables us to achieve powerful movements necessary in throwing a cricket ball at 100 mph or lifting 200 kg overhead as readily as the intricate control required in throwing a dart or playing the violin.

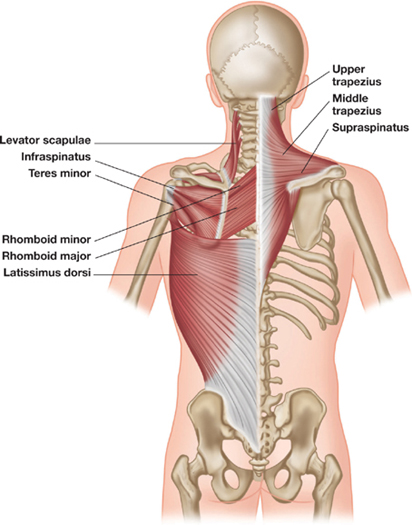

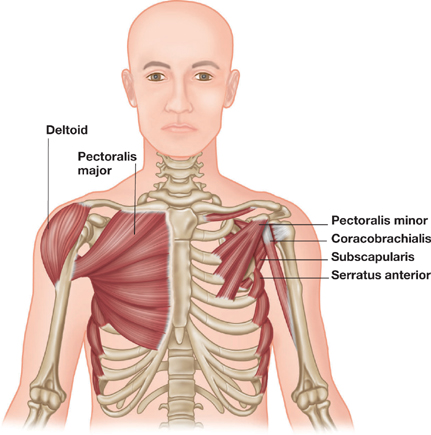

Limitations in any of the soft tissue components of the shoulder girdle will eventually lead to abnormal movement and the potential for pain and disability at worst and reduced performance at the least. Although the capsule and the ligaments can be a source of restriction, the focus here is on muscular and tendinous tissue restrictions. The shoulder girdle utilises approximately 16 interdependent muscles, and the glenohumeral joint has the greatest ROM of any joint in the body.

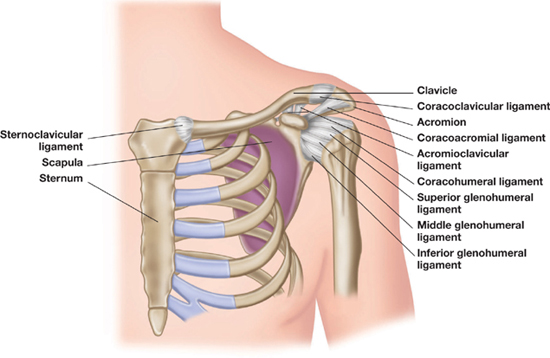

Figure 2.1: Shoulder girdle complex.

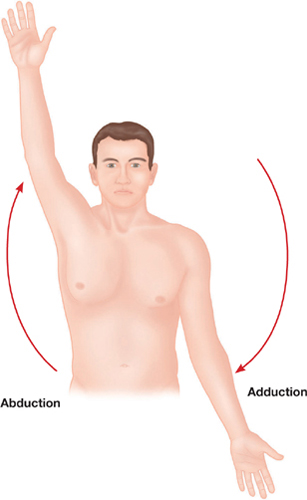

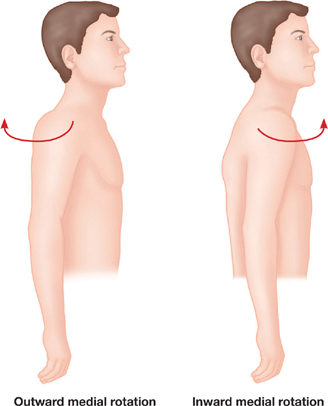

There are a number of fundamental gross movements (osteokinematics) associated with the shoulder girdle complex. These movements are normally measured or observed via the location of the arm with respect to the trunk and represent the ROM at the glenohumeral joint. However, underlying these movements are the arthrokinematics at joint surfaces and the gross movements of the scapula and clavicle. These individual movements, which are the result of a complex pattern of muscle activation, combine to create a multitude of integrated patterns of movement that give the shoulder girdle its ability to provide stability with flexibility.

The following section examines the basic gross movements and the arthrokinematics at the associated joints, along with the muscles involved and essential integrated patterns of movement used in clinical settings to identify potential issues.

| Flexion | External humeral rotation |

| Extension | Internal humeral rotation |

| Lateral flexion (abduction) | Adduction |

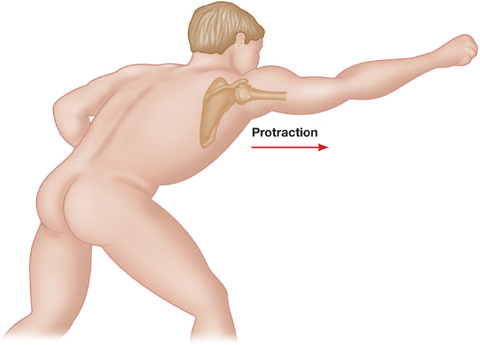

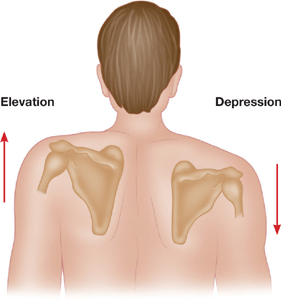

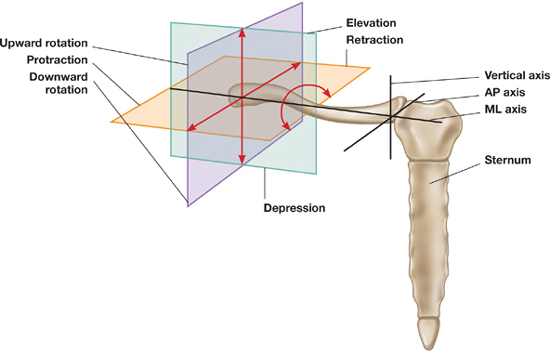

| Protraction (abduction) | Elevation | Upward rotation |

| Retraction (adduction) | Depression | Downward rotation |

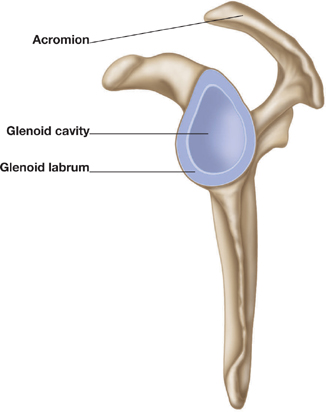

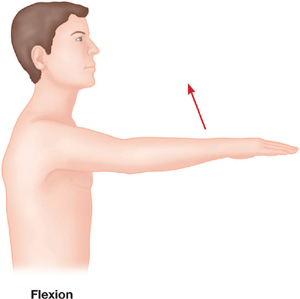

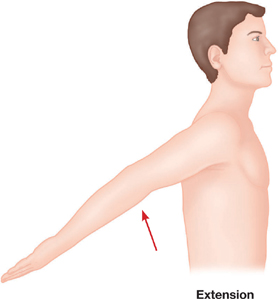

Figure 2.2: Shoulder girdle movement.

Figure 2.3: Scapular motion.

| Elevation | Downward rotation (axial rotation) | Protraction |

| Depression | Upward rotation | Retraction |

Figure 2.4: Movement of the clavicle.

Apart from depression of the clavicle by the subclavius muscle, movement of the clavicle is determined by its relationship with the movements of the shoulder girdle as a whole. However, restrictions in attached muscles will affect its ability to move as required for full function of the shoulder girdle.

Arthrokinematic movements are those that take place at the joint surfaces and are key to the overall gross movements.

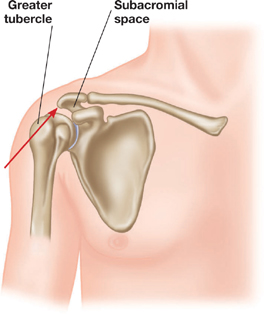

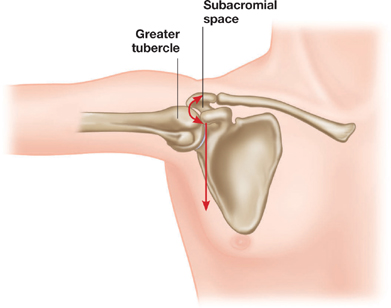

• Glenohumeral – between the humeral head and the scapula’s glenoid fossa. For the humerus to be abducted in the plane of the scapula (lateral flexion), the humeral head must also translate downwards and laterally (externally) rotate. If either of these does not happen, signs of impingement are seen and felt as the contents of the subacromial space are compressed by the head of the humerus.

Figure 2.5: Glenohumeral joint arthrokinematics.

• Sternoclavicular – between the sternum and the clavicle. Movement of the clavicle is dependent on the arthrokinematics taking place at the sternal notch and the clavicular head. Protraction of the clavicle occurs with posterior roll and anterior movement of the clavicular head; retraction occurs with posterior rotation of the clavicular head and anterior movement of the body.

Raising the arm laterally – an essential gross movement – depends on the arthrokinematics at the glenohumeral joint, along with movement of the scapula and clavicle. The key pattern observed is known as ‘scapulohumeral rhythm’; without this function, the total movement of the shoulder girdle is impossible. The scapula should move approximately in a 1:2 ratio with the humerus in lateral flexion in the scapula plane. The scapula thus provides 60 degrees of upward rotation and the glenohumeral joint 120 degrees to make the full 180 degrees. Although there is a difference of opinion regarding the exact ratio, there is agreement that a pattern exists and can be used by clinicians to identify abnormal patterns of movement.

Figure 2.6: Scapulohumeral rhythm.

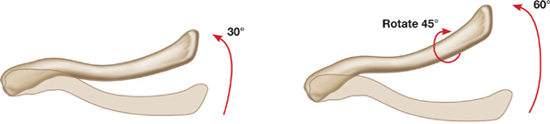

Figure 2.7: Clavicular rotation.

With an upward rotation of the scapula there must also be a concomitant upward elevation of the clavicle: this is approximately 40 degrees for a scapular rotation of 60 degrees. At the same time, the clavicle must also rotate posteriorly to utilise its crank shape to increase movement.

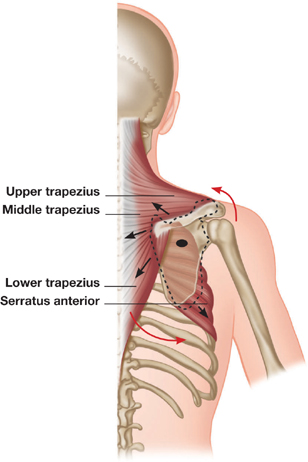

As part of the integrated movement of the shoulder girdle, groups of muscles work in synergy to provide ‘force couples’. Restrictions in any of these muscles will affect these balancing force couples. This will prompt abnormal compensatory movements to occur, having long-term effects on associated structures, which then lead to pathology and reduced performance.

The upward rotation of the scapula requires the upper trapezius to work in tandem with the lower trapezius, and for total humeral-trunk elevation the serratus anterior must balance the whole of the trapezius muscle.

Figure 2.8: Trapezius-serratus relationship.

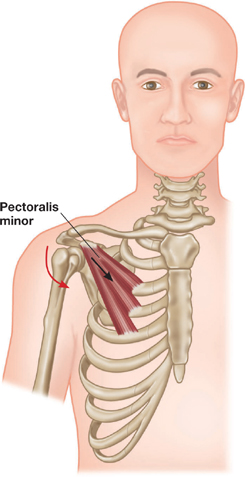

Downward rotation of the scapula is created by the pull of the levator scapulae along with the rhomboids, which would create adduction of the scapula without the balancing effect of the pectoralis minor muscle.

Figure 2.9: Pectoralis minor-levator scapulae relationship.

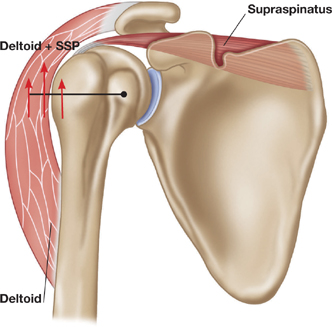

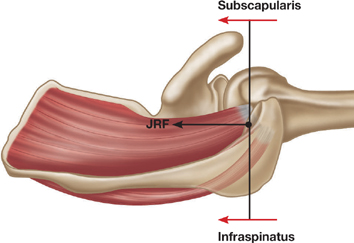

The rotator cuff muscles work with the deltoid in the frontal plane and with each other in the transverse plane. They act to stabilise the joint as movement is initiated and the arm abducted.

Figure 2.10: Deltoid-supraspinatus (SSP) relationship.

Figure 2.11: Rotator cuff relationship, the joint reaction force (JRF) of both muscles working together.

Figure 2.12: Shoulder girdle muscles.

When muscles are not capable of fulfilling their normal roles, it is often through weakness, tightness, injury or a pathological change brought about by disease. In this book we are concerned with restrictions in muscles and other soft tissues that prevent full movement taking place around a joint complex.

The modern golf swing often tends towards a greater degree of shoulder girdle rotation than in the past. The progress of muscular movement in a golf swing can be summarised as scapulothoracic – glenohumeral -thoracic spine, and then reversed on the downswing and follow-through. Any restriction in the shoulder girdle will reduce performance in two ways. The first is a requirement for greater muscular energy to overcome restriction, which becomes tiring when playing 18 holes. The second is an inability to actually align the upper and lower body for an efficient swing. Even holding the head still to focus on the ball will be impossible without adequate shoulder girdle movement.

It is likely that restrictions in the shoulder girdle will translate down to the low back as the golfer attempts to compensate for reduced shoulder girdle flexibility by way of low back rotation; this may in part explain the prevalence of low back problems.

Source: Adapted from A. McHardy & H. Pollard, 2005, ‘Muscle activity during the golf swing’, Br. J. Sports Med., 39, pp. 799-804.

Shoulder impingement problems are common in swimmers. A potential cause is tight pectoral muscles, resulting in the development of a ‘round-shouldered’ posture. This can lead to an abnormal positioning of the humeral head and an increased chance of acromioclavicular impingement during the overarm stroke.

The basic movement in front crawl involves protraction, and upward rotation of the scapula as a result of strong serratus anterior action. The pectoralis major activates, adducting and extending the humerus, while internal rotation should be balanced by the external rotation of the teres minor. Restriction in any of these muscles will have an impact on the coordinated action required to achieve an efficient stroke.

For most people, brushing the hair is a simple task; however, it can be painful (or impossible) to do if there are restrictions in any number of the shoulder girdle muscles. Restriction in the subscapularis will reduce its ability to stabilise the glenohumeral joint and affect the movements which are necessary for holding and moving the arm when brushing the hair. The scapulohumeral rhythm is disrupted, and essential lateral rotation and horizontal adduction of the humerus, necessary for achieving a ‘hair brushing’ position, is either reduced or impossible. Pain referral patterns into the upper arm are also common.

Make a note of the subject’s natural position when standing and when seated. Check through the subject’s active ROM, both the shoulder girdle and the shoulder joint. Passive STR is a good way to warm-up the tissues; however, with any area where there is a painful restriction, such as in shoulder rotation, it is advisable to start with active STR. In this case the subject can move comfortably as the therapist slowly guides him through a range of appropriate movement patterns.

It is recommended to perform STR to the shoulder girdle muscles prior to the shoulder joint. Release of restrictions in the shoulder girdle will improve scapular and clavicular movements, as well as improving the range and control of glenohumeral joint movement.

1) Hold the subject’s elbow and grasp between the serratus anterior and the latissimus dorsi by trying to lift the latissimus dorsi slightly; abduct the arm passively. For active STR ask the subject to raise his elbow while keeping his hands together.

• Ensuring that the serratus anterior is not sticking to the latissimus dorsi will improve scapula movement.

• Only a small movement may be required.

2) Hold the elbow and apply a CTM lock, using the whole hand, across the surface of the muscle; move the elbow back to retract the scapula. Reinforce the hand and apply a CTM lock; ask the subject to retract his scapula by drawing his elbow back. Use a CTM lock to address the attachments on the anterior surface of the scapula.

• Avoid pressing into the ribs; keep the hand relaxed as it melds around the shape of the rib cage.

1) Use a soft fist to apply a CTM lock across the surface of the ribs and into the serratus anterior; ask the subject to retract his scapula and abduct his shoulder.

1) With the shoulder at 90 degrees, cup the subject’s elbow with one hand. Lock in with the heel of the other hand or knuckles; horizontally abduct the shoulder. Shorten the muscle by horizontally adducting the shoulder prior to the lock, or position the subject at the end of the couch for greater range. Address the sternal attachments with a CTM lock using one or two phalanges.

• Even on larger-muscled people this can be a sensitive area to work, so check your speed!

• STR through clothing or towels is useful when treating females.

2) With the shoulder at 90 degrees, gently take hold of the subject’s hand and lock into the clavicular fibres with a soft fist; laterally rotate the shoulder.

3) Gently grasp the pectoralis major towards the insertion; ask the subject to flex or horizontally adduct the shoulder. Apply a CTM lock at the bicipital groove insertion; direct the subject into a minimal stretch.

1) Prior to treatment, ensure that the pectoralis major has been ‘released’. Use broad surface knuckles, or fingers, to drop in off the coracoid process. Ask the subject to actively retract the scapula into the couch.

2) Slowly direct fingers underneath the pectoralis major towards the third rib attachment and guide the subject to retract the scapula. Repeat, directing fingers towards the fifth rib.

• Do not force through resistant tissue. Move slowly to reach the pectoralis minor fibres. Stop before reaching the muscle if there is too much tissue congestion and perform STR at that level.

1) Use the first phalange to direct a CTM lock down from the clavicle. Ask the subject to elevate his scapula.

1) Hook fingers under the border of the lower trapezius and ask the subject to elevate his shoulder.

• Although this part of the trapezius rarely becomes tight, there are often restrictions at the border. Ensuring that there are no adhesions here will facilitate strengthening programmes targeted at the lower fibres.

1) Gently grasp the upper fibres of the trapezius; ask the subject to slowly depress his scapula.

2) Ask the subject to shorten the muscle first by shrugging his shoulder. As he does so, support the scapula or flexed elbow to relax the tissue prior to locking in. Use fingers to lock in; ask him to relax his scapula or to gently push down into the supporting hold.

3) Try a lock close to the acromion, engage the anterior fibres of the upper trapezius, address the spine of the scapula with a CTM lock and apply a lock away from C6/C7.

• See here for STR to upper trapezius with head movement.

1) Stand at the head of the couch and cup the subject’s shoulder with one hand. Lock into the muscle with the heel of the other hand and push the shoulder down to depress the scapula.

2) Still at the head of the couch, liberate both hands and use a reinforced thumb to drop into the muscle. Ask the subject to slide his hand down the side of his leg to depress the scapula.

3) From the side of the couch, cup the subject’s anterior shoulder with one hand and use the fingers of the other hand to hook into the muscle; pull the shoulder down into depression.

• Do not force the shoulder into medial rotation if there is any restriction in this movement.

4) Stand at the head of the couch. With one thumb reinforced with the other, lock in deep to the upper trapezius towards the insertion of the levator scapulae at the superior medial angle of the scapula; ask the subject to slide his hand down the side of his leg to depress the scapula.

1) Ensure that the upper fibres of the trapezius are warmed up. Grasp the lower angle of the scapula with one hand and elevate the scapula. Use fingers or a reinforced phalange to apply a deep pressure towards the levator scapulae at the attachment of the anterior superior angle of the scapula. Gently depress the scapula.

2) The same can be done by directing the lock underneath the anterior fibres of the trapezius. This can be painful so it is essential to work slowly. Do not force through a restriction.

• Make sure that the upper fibres of the trapezius are ‘released’ prior to working on the levator scapulae.

• See here for further STR on the levator scapulae with neck movement.

1) Use fingers to lock into the fibres of the upper trapezius and depress the scapula by gently pulling it down.

1) Support the subject’s clavicle and use a gentle fist, the heel of the hand or an elbow to lock into the muscle with a broad surface lock. Instruct the subject to move his arm forwards, or across his body, to protract and rotate the scapula as necessary.

2) Use a knuckle, a reinforced thumb, fingers or an elbow to apply a deeper lock. Lock in and away from the medial border of the scapula. Lock in and away from the spinous processes. Ask him to protract his scapula.

• Vary the direction or the lock. Consider the direction of the fibres of the trapezius, running in a ‘V’ from the spinous processes (C7–T6) to the scapula, and of the deeper rhomboids (C7–T5), running obliquely to them.

• Vary the arm movement to facilitate a particular movement of the scapula, from miniscule protraction of the scapula with the arm fixed, to broad arm movements across the front or the body.

1) In prone position, subtle CTM locks can be used to lock away from the vertical border of the scapula as it is actively protracted into the couch. Careful ‘reading’ of the tissue in deciding the direction, depth and speed while attaining the lock will provide a fast release, even with minimal movement of the scapula.

• For a greater ROM, try positioning the subject on the edge of the couch so that he can move his arm underneath it, to protract his scapula.

1) Use a thumb reinforced with the other to apply a lock into the muscle. Ask the subject to move his arm into horizontal adduction to protract the scapula.

• This is a good position for progressing to release of the deeper erector spinae muscles.

1) Position the subject at the end of the couch and stand facing his middle deltoid. Ask him to abduct the shoulder to 90 degrees. Grasp his whole upper arm and use a thumb reinforced with the other one to lock into the medial fibres, drawing down and away from the clavicle. Ask him to adduct his shoulder.

2) Stand behind the couch to engage the posterior fibres away from the clavicle as the subject flexes his shoulder; stand in front to engage the anterior fibres as the subject extends his shoulder. Keep the elbow flexed for ease of movement.

1) Stand at the head of the couch. Ask the subject to abduct his shoulder while his elbow remains flexed. Grasp the shoulder with both hands and lock in, with a reinforced thumb, away from the clavicle into the medial fibres of the deltoid. Maintain the lock as the subject adducts his shoulder.

2) Stand at the side of the couch. Gently hook fingers into the fibres of the anterior deltoid and direct it towards the deltoid tuberosity. Ask the subject to extend his shoulder while the elbow remains flexed. Lock into the anterior fibres and ask the subject to laterally rotate his shoulder.

3) Use a reinforced thumb to engage the posterior fibres of the deltoid; ask the subject to flex his shoulder while the elbow remains flexed.

1) Stand at the head of the couch and grasp the subject’s hand, with the elbow and shoulder both at 90 degrees. Use fingers to apply a traversing lock into the anterior deltoid and laterally rotate the shoulder. This can be done actively, but passive STR here does provide a very relaxing release.

• Do not go too deep with the lock.

1) Ensure that the upper fibres of the trapezius have been released. Stand at the head of the couch with the subject’s shoulder at 90 degrees. Use one thumb reinforced with the other to slowly apply a deep lock, through the trapezius muscle and into the supraspinatus. Ask the subject to adduct his shoulder.

• Try a lock close to the acromion and one closer to the superior angle of the scapula.

1) Ensure that the upper fibres of the trapezius have been released. Ask the subject to abduct his shoulder to 90 degrees. Cup fingers on top of the trapezius; reinforce them with the fingers of the other hand and slowly apply a deep lock into the supraspinatus. Ask the subject to adduct his shoulder.

• Avoid crushing into the tissue: try ‘tweezing’ in with the fingertips. If the trapezius is too dense to acquire a lock in a shortened position, do not abduct the shoulder first. Perform STR with a minimal stretch by asking the subject to adduct his shoulder by pushing his arm into his side.

2) Use a CTM lock to drop inferiorly off the acromion, deep to the deltoid fibres, onto the surface of the tendon insertion; ask him to adduct his shoulder into his side.

• Putting the shoulder in medial rotation exposes the tendon, making it easier to locate.

1) Stand at the head of the couch with the subject’s shoulder at 90 degrees. Apply a CTM lock with a reinforced thumb or fingers across the fibres of the infraspinatus. Ask the subject to medially rotate his shoulder. Perform three or four locks here, ensuring that one is performed close to the insertion point at the greater tubercle (deep to the posterior deltoid).

• This is a very sensitive area and locking into the muscle will often produce a trigger point. Do not rush, and give the subject a break between each lock.

1) Stand at the side of the couch with the subject’s arm horizontally abducted to 90 degrees and the elbow flexed. Use fingers reinforced with the other hand to slowly attain a CTM lock into the subscapularis on the anterior surface of the scapula. Ask the subject to laterally rotate his shoulder.

2) With his arm by his side, apply a CTM lock to the tendon of insertion. Lock away from the lesser tubercle (in between the two biceps tendons and deep to the anterior deltoids); ask him to laterally rotate his shoulder.

1) Gently grasp the borders of the latissimus dorsi where it converges towards the humerus. Ask the subject to abduct his shoulder.

• Ensure that a lock is performed close to the origin on the inferior angle of the scapula as this will help facilitate scapula movement.

• On people with a flexible latissimus dorsi, it is hard to feel a local lengthening. Try to feel the border of the latissimus dorsi and add in some lateral rotation for more stretch (ask the subject to try to place his hand on his head).

2) Perform locks all the way down to the lumbar spine. Use fingers to curl under the lateral border of the muscle, and use CTM locks to engage the thoracolumbar fascia.

• Try working close to the posterior iliac crest.

• During shoulder abduction, try to feel the tissues moving when locked in at the origins on the lower three ribs.

3) Engage the muscle and guide the subject into active shoulder abduction. A more precise stretch will be obtained by keeping the elbow flexed and the hands together on the couch while active abduction is performed.

• Try using a CTM lock at the origin on the scapula.

• This is a great position for addressing the insertion. Consider the teres major along with the latissimus dorsi attachments and add in an active lateral rotation for a further stretch.

1) Use a broad surface lock, such as the whole hand, slightly cupped, or a gentle fist to engage the latissimus dorsi. Ask the subject to abduct his shoulder. Address the scapula attachment and consider the lateral borders of the muscle as well as the muscle belly.

2) Use a knuckle close to the origin at the spinous processes to perform a CTM lock. Ask the subject to abduct his shoulder. Work down from T6 to the iliac crest.

1) Cup the subject’s flexed elbow with one hand or hold the wrist. Lift it up to flex his shoulder and lock fingers into the tendons of the anterior shoulder. Apply a lock across the coracobrachialis, away from the coracoid process, and drop the elbow passively to extend his shoulder. Apply a lock in the same way for the biceps brachii; use a CTM lock to distinguish between the two tendons.

• Try abducting the shoulder to locate the coracobrachialis more easily.

• Try laterally rotating the shoulder to locate the long head of the biceps.

• Position the subject with his shoulder off the side of the couch. Gently tweeze between the tendons as the subject actively extends his shoulder.

Grasp the subject’s flexed elbow with one hand. Lock in away from the origin of the long head of the triceps; move the shoulder into flexion.