South-East Asia Command: The Winning Card

1945

. . . properly organized air supply . . . was to prove the winning card in that theatre.

Bernard Fergusson, The War Lords (ed. Michael Carver)

On 17 September 1944 Portal informed Sinclair that the Americans had withdrawn their objection to a British Air Commander-in-Chief of South-East Asia Command (SEAC). Churchill had agreed to the appointment of Leigh-Mallory, who had headed the Allied Expeditionary Air Force during the invasion of Normandy. At about 9 a.m. on 14 November Leigh-Mallory left Northolt for India in an Avro York. Shortly after midday, while flying in cloud through a snowstorm, it struck a ridge in the Belledonne Mountains, some fifteen miles east of Grenoble. The York somersaulted down a steep rocky slope, disintegrating as it went. Everybody on board was killed. A Court of Inquiry into the accident found that the weather had been very poor on the day of the accident, but that Leigh-Mallory ‘was determined to leave and he is known to be a man of forceful personality’; Portal added that he had had no need to make such haste, risking his crew as well as himself and his wife: ‘the desire to arrive in India on schedule with his "own" aircraft and crew overrode prudence and resulted in this disaster.’

On 21 November, when it was clear that the York was lost, Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander, SEAC, had informed Portal that he and Richard Peirse (the man Leigh-Mallory was to have succeeded) agreed that a new appointment should be made as soon as possible. Meanwhile, Guy Garrod (Peirse’s deputy) took over and Peirse returned to England. Slessor was offered the job, but preferred to return to the Air Ministry as Air Member for Personnel. As late as 26 January 1945, Park signalled Garrod to congratulate him on his appointment as Peirse’s successor, which had been announced in the Cairo newspapers. On the following day, however, Sinclair told Garrod that he was to succeed Slessor at Caserta and that Park was to be the Air C-in-C, SEAC. Garrod was reluctant to leave and Mountbatten reluctant to release him, but they both gave way; Park signalled Garrod on 31 January to thank him for his best wishes. For a second time in the war, Park’s career was thus crucially affected by Leigh-Mallory.

Douglas Evill (Vice-Chief of the Air Staff) instructed various Air Ministry officials on 11 February to help Park obtain as much information as possible about air staff matters in SEAC. Portal himself discussed with Park the RAF’s postwar policy in India. On 14 February he was received by the King at Buckingham Palace and invested with the insignia of the KCB. Later that day he attended a meeting at the Air Ministry and at 10 a.m. on the 17th he and Dol left Northolt – by Dakota – and flew via Malta and Cairo to Calcutta, to take part in an important conference with Mountbatten and all the other principal Allied commanders in South-East Asia.1

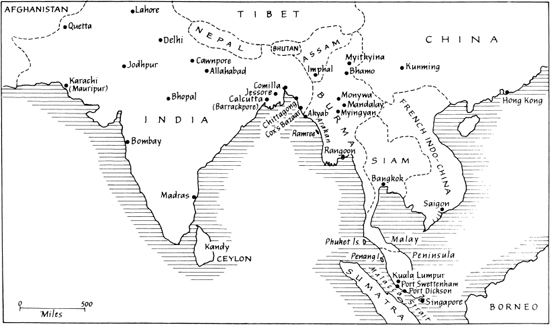

In welcome contrast to the shortage of men and materials which had plagued him at Uxbridge in 1940 and Malta in 1942, Park found himself master of vast resources in his new command. The tasks ahead of him, however, were hardly less daunting. He had arrived at Uxbridge and Malta in times of crisis and once again, as soon as he took his place at a conference in Calcutta on 23 February 1945, he was immediately required to make a major decision. It was a decision which had to be made, moreover, before Park had had a chance to become familiar with either his new duties or his new resources. However, he did not hesitate. Quite simply, he agreed to supply General Slim’s Fourteenth Army from the air throughout its advance on Rangoon.

It was an immense undertaking, calling for the greatest supply operation of the war. Park’s aircraft would sustain an army of more than 300,000 men, fighting in a country mostly unsuitable for aerial operations. But Park agreed to carry nearly 1,900 tons of supplies every day from 20 March and a little over 2,000 tons every day from 1 April. If the Japanese could be beaten in the central Burmese plains around Mandalay in a short campaign, the port of Rangoon might fall before the monsoon began in June and the reconquest of Burma would be practically complete. The penalty for failure would be severe: if Rangoon was not taken by June, Park’s transport squadrons would have to continue supplying the Fourteenth Army throughout five months of steady rain.

Christopher Courtney, Air Member for Supply and Organization, reported to Portal in March on his tour of South-East Asia. He doubted if the major part being played by Allied air forces in that theatre was generally appreciated. Slim’s army was almost entirely maintained by the American Combat Cargo Task Force, and the British 221 Group provided most of his artillery support. One heard constantly, said Courtney, about the difficulty of supplying the army by a single poor road, but it was not in fact used for that purpose. One continually heard also that a brigade had captured a village and counted so many dead, when in fact it was the RAF which had overcome the opposition, causing most of the casualties and leaving the army to walk in and occupy the place.2

Park made a short speech to his new staff at his headquarters in Kandy, Ceylon, on 2 March. He thought it wise when going to a new command, and this was the sixth he had had during the war, to meet the staff and explain his methods and ambitions. One function of a higher formation, he said, was to simplify paperwork and organization so that lower formations, where the fighting was done, did not get confused. He had already landed at five airfields in ACSEA (Air Command, South-East Asia) and at two of these the commanding officers had said they did not know who their masters were. ACSEA was, necessarily, a complex machine, but COs should know their place in it. A second major function was to concentrate on essentials. ‘You never saw such a volume of paper passing as at Middle East HQ when I went there in January 1944,’ he recalled. ‘We reduced it by half, missed nothing essential (indeed, we had more time for it), got round the units more and kept fitter.’ The further one got away from units in the line, he said, the greater the tendency to become inflexible and fall into routine responses.

On his appointment to this job, Park continued, he was called home to the Air Ministry for ‘consultations’: these consisted of dashing from one department to another during six hectic days and collecting a deal of paper. He had thought it a bind until he realized how much the Air Ministry knew about the command; it was eager to help and contrary notions must be forgotten. ‘Bellyaching signals’ could easily be dictated at the end of a long day, he said, and anyone who felt the need to blow off steam should carry on dictating them – but leave them to be read through the next morning before despatch. He knew he sounded like a schoolmaster, but the Air Ministry’s goodwill was important and he for one would try to set an example. Finally, Park appealed to everyone to have teamwork in mind: at headquarters, throughout the command, and with the army, the navy and the Americans.

Having delivered himself of these admirable sentiments, Park spent a week touring his enormous command with the intention of putting them into practice. He had a reputation for going to see what was actually happening in any units under his command and would fly many thousands of miles during the next year from his headquarters in Kandy (later in Singapore) to Quetta in the north-west, the Cocos Islands in the south and Hong Kong in the north-east. Given the primitive or isolated conditions under which most units operated, exacerbated by intolerable heat and dust alternating with intolerable rain and mud, Park’s obvious concern for the living and working conditions of all ranks fitted him well for what must then have been, in both senses, the RAF’s most demanding command. By the end of March, he had already travelled over 17,000 miles in all types of aircraft, motor vehicles and watercraft. His wife had the same desire to see for herself and had visited many hospitals, sick quarters, canteen and welfare centres in Ceylon and India. Her cheerful support helped to keep him going.

During his first tour, Park examined all matters, great and small. At Barrackpore (near Calcutta), for example, tools were spread carelessly around workshops; at Jessore, there had been only three ENSA shows in eighteen months; and at Digri, proper engine handling, good training and experience had increased Liberator bombloads by up to 800 lbs, but there were no means of making hot coffee for long flights and no fans for ground crews working in very high temperatures. He inspected the casualty evacuation service at Comilla, across the Ganges, observing that aircraft were being refuelled while stretcher cases were still on board; in view of the fire risk, this should not be done. Unlike some officers, junior or senior, Park never carried out his inspections as formalities, completed at a brisk trot. He took the time and trouble necessary to notice what was going on. Fecklessness always angered him. For example, a squadron newly arrived from England complained that it had had no beer ration although stocks lay in Comilla two miles away. At Chittagong, an American base, he saw a jeep fitted with VHF radio which took over aircraft control on the ground, directing taxying, thus freeing the control tower to concentrate on traffic in the air; could not similar arrangements be made for busy RAF airfields?

He went to Akyab in Burma for talks with the Earl of Bandon (AOC, 224 Group) and thence to Monywa to meet an old friend, Stanley Vincent (AOC, 221 Group). Only four Spitfire squadrons were available to cover the whole area of operations of the Fourteenth Army, Vincent told him, and many pilots were very tired. If the Japanese used their fighters properly, losses in transport aircraft would be heavy. Park also visited the headquarters of the US Tenth Air Force at Bhamo in north Burma and called at Myitkyina East to watch the despatch of supplies across the Hump to China. As at all American stations, he was greatly impressed by the amount of equipment available, domestic as well as military, and the efficient methods employed. When he returned to Barrackpore, he learned that the aeroplane in which he was to fly to Kandy had been sent empty down to Calcutta from Delhi. This thoughtless waste of space exasperated him: if a little initiative had been shown, a whole planeload of personnel committed to the crowded railway service from Delhi to Calcutta could have been given a pleasant surprise.

Overall, his tour confirmed the reports of poor conditions in his command which he had read in England. It was still not possible to buy razor blades, toothpaste or soap except at fantastic prices; beer (so-called) from Indian sources was rationed to three bottles a month; there were no canteens at most forward aerodromes, no sports facilities and the mail service was at best irregular; there were few wirelesses, books, newspapers, rest rooms or cinemas. In the South Pacific, where transport difficulties were as taxing as in Burma or India, Australian and American forces had numerous live shows arranged for them right up to the front line. But virtually nothing was done in South-East Asia, where at least seventeen per cent of personnel were ineffective because of sickness caused by the alien climate and bad conditions. ‘I have frequently heard officers, and especially senior officers, boasting that we look after our men better than the Army,’ he wrote on 24 March. ‘It seems to me that some units pay less attention to the well-being of their men than we did to our horses when I was a junior officer. It was a matter of pride in those days that we got the very best rations and fodder for our men and horses and a bit extra just for luck.’

In Burma – as in Britain, Egypt, and Malta – Park showed himself a forceful, resolute and highly visible leader. Although his responsibilities were heavier than ever and his forces far more widely scattered, Park’s long, lean figure and smiling face were soon familiar to many and he was no less ready to sit with a group of pilots at dispersal, discussing operations and listening to opinions or complaints. Flight Lieutenant Peter Ewing, a Mosquito pilot in 221 Group, recalled his surprise at Park’s consideration for his men. Ewing was awarded the DFC and Park took the trouble to write personally to congratulate him and then again to send him a piece of DFC material, knowing that Ewing would find it difficult to obtain. Most important, Ewing emphasized that under Park more determined efforts were made to keep everyone informed about the overall progress of the Burma campaign.

That campaign was going well and during March it was recognized that the time had come to look beyond Rangoon and plan for operations in Malaya. The problem was how to exploit the present advantage without large reinforcements from Europe. Park therefore encouraged action to release manpower from his own rear areas by disbanding redundant units, reducing establishments and making non-combat zones bear the brunt of shortages. The base organization in India and Ceylon was severely trimmed in order to build up the strength of the advanced striking forces for the battles ahead. The reoccupation of Burma, he said, was largely a land battle to recover territory and destroy an army, but after Rangoon was taken, the emphasis would be upon seaborne and airborne assaults intended to seize bases for the capture of Singapore and the reopening of the Malacca Strait.3

Park wrote a ten-minute talk in March on the air forces in SEAC for use by the BBC, which he would send to the Air Ministry if Mountbatten approved. I really think it is one of the best I have read,’ replied Mountbatten, ‘and quite first-class and it has my wholehearted backing.’ The Air Ministry approved the text with certain changes. Where Park had written: ‘I know from personal observation that this is not generally known in the United Kingdom nor in fact outside the South-East Asian theatre,’ he was required to say: ‘I know that at home exploits of the Allied Air Forces are followed with keen interest and admiration.’

Meanwhile, on 20 March, he had written to Beaverbrook. He had just completed a tour around Burma, he wrote, and learned for the first time how dependent the army had been on air support for its victory in the battle for Mandalay. Undisputed aerial superiority enabled close support squadrons to concentrate on accurate firing and also permitted the carriage of whole divisions up to the battle zone, together with the bulk of their supplies. Flying over forward areas, Park was struck by the congested roads, uncamouflaged dumps and Mechanical Transport parks right up to the front line, whereas on the enemy side no Japanese dared show a leg by day. He was so impressed, Park concluded, that he had written an account for the BBC to tell the world. On 29 March the account was broadcast by All-India Radio; the BBC, however, never did broadcast it. This confirmed Park’s suspicion that the words foisted on him by the Air Ministry were simply not true: there was both ignorance and lack of interest in Britain about what was going on in South-East Asia. His brief, authoritative account of well organized and highly successful attempts to expel invaders from British territory, written with a British audience in mind, were rejected by British radio.

Nevertheless, his efforts to publicize the work of the air forces in SEAC gradually bore fruit. On 17 April he told transport squadrons of Eastern Air Command in Arakan that on the Western Front ‘the Armies of Liberation are advancing under the protecting wings of the Air Forces. But here in Burma our Armies are advancing on the wings of the Allied Air Forces.’ These words (later to be much quoted, usually without acknowledgement) were taken down by a reporter and broadcast over All-India Radio on the 24th. Beaverbrook informed Park on the 26th that the astonishing part played by air transport in Burma was becoming clearer to the British public. Although attention was inevitably fixed on the final stages in Europe, the swift succession of Burma victories was another cause for rejoicing. ‘Nor is it without remark,’ he added, ‘that the increased pace of the Burma Campaign has coincided with your own arrival in that theatre of operations.’4

Park’s relations with Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese, GOC-in-C Allied Land Forces, South-East Asia, soon became uneasy. He received a signal from William Dickson, an Assistant Chief of the Air Staff at the Air Ministry, on 25 March informing him that Leese had signalled the War Office to say that he would need more transport aircraft to ensure decisive success in Burma. Dickson told Park that he was surprised by this statement because the Air Ministry had met in full Mountbatten’s request for transport aircraft. Park replied that the air forces had lifted every ton of the amount agreed with the army and that Leese should be told by the War Office to follow the normal procedure of complaining about another service only through Mountbatten and with the knowledge of that service. He assured Dickson that the closest cooperation existed between Slim, the various corps headquarters and the air forces – and hoped that when Lesse moved his headquarters from Calcutta to Kandy, as Mountbatten and Park had asked him to, they would get the same cooperation from him.

On 4 April Park reported to Portal. Fighting spirit, he said, was equally good in both British and American squadrons, but the Americans had more and better equipment and more ground transport. Since they served only a two-year tour and got more air transport for local leave, they were fresher as well as more comfortable than the British. Park’s groups suffered from a lack of experienced administration officers and the many changes of organization in the last six months had caused much confusion. Maintenance units were overloaded with equipment of every kind, but much of it was obsolete or deteriorating. Provided an even flow of supply was kept up, he could effect great savings in manpower, works services, storage space and airfields – not to mention money – by cutting down reserve stocks.

A week later, he sent Portal a ‘strictly personal’ signal to warn him that Mountbatten had signalled London alleging that extraordinary efforts would be needed to cover the deficit in air supply. That signal, said Park, had been sent without his knowledge and did not represent the correct situation. He had already strengthened the maintenance backing by transferring to Dakotas personnel and resources from other aircraft types and had also borrowed Dakota spares from the USAAF Servicing Command and improved field maintenance. There should be ‘absolutely no deficit in air supply’ because any additional load caused by airborne operations would be accepted by the transport squadrons which could increase their present scale of effort for a short time. Any ill effects of this overload would be made good by the two extra Dakota squadrons promised Park for early May. Mountbatten’s signal, Park concluded, had probably been intended to ‘ginger up’ the Air Ministry; it would not have been sent from Kandy, ‘where the true facts are well known.’ Park’s analysis impressed Portal and also Dickson, who informed the Joint Planning Staff that it ‘disposed of the criticisms levelled by Admiral Mountbatten at alleged shortcomings in air supply and backing’; consequently, Mountbatten was told by the Chiefs of Staff that ACSEA would inform him of arrangements made with the Air Ministry regarding air transport.

Park appointed a Maintenance Investigation Team in April to examine and compare methods and rates of aircraft replacement, repair, inspection and wastage in the RAF and USAAF, in order to see if the performance of the British organization could be improved. His aim, he told Leslie Holl-inghurst, head of Base Air Forces, South-East Asia (BAFSEA), was to ensure that every hundred American aircraft allotted to the RAF produced as good a flying effort as an equal number of USAAF aircraft doing the same job. He knew that the Americans had more of everything:

All right, let us shout and bullyrag the Air Ministry until our squadrons enjoy the same good facilities as our Allies. Let us raise our standards and go one better than our American cousins, but for heaven’s sake don’t let us sit down and accept the lower standards of the past.5

Park wrote to Slessor, his old sparring partner, on 21 April to say how grateful he was for his warning about ‘a certain high-ranking General [Leese] who, you said, had old-fashioned ideas about the control of air forces.’ Park gathered that Leese had been difficult in Italy and he knew that Garrod had found him hard to handle. Leese had set up his headquarters at Hastings Air Base, near Calcutta, alongside those of George E. Stratemeyer, who had unfortunately been given operational control of Allied air forces long before Park had reached South-East Asia. Stratemeyer, as an American airman, was used to obeying orders from the army and Leese was now dominating him. Although Park had persuaded Mountbatten to order Leese to move to Kandy, this would not happen until after the fall of Rangoon. Meanwhile, Park went on, he was educating Stratemeyer into a practice of ‘getting the army to state the problem or the effect required and to leave it to the Air Force Commander to decide the method of execution.’

Within a week of writing this letter, Park seized a chance to put Leese firmly in his place. Leese had complained to him about the communication aircraft provided by RAF Burma, but when Park had last been in Calcutta, Leese had expressed satisfaction with them. Park wrote, ‘Now you fire a full broadside, accusing the RAF communication units both in Italy and in this theatre of being unsatisfactory and far less efficient than their American counterparts.’ Leese was upset because a few Vickers Warwicks had been used recently instead of Dakotas, which had had to be returned to transport work to meet ever-increasing demands for supplying the land forces; demands, said Park, which were ‘due partly to the inability of the land supply system to carry the tonnage promised at the Calcutta conference of 23 February.’ Leese had made serious allegations against the morale and ability of communication pilots and Park challenged him to produce examples. If a low accident rate was any guide, they must be reasonably competent: only one army officer had been killed in the past year while flying. How many, asked Park, had been killed in road accidents during that time?

Leese thought it essential for commanders to have their own aircraft, but Park did not and neither did Mountbatten. Leese knew perfectly well that Park had had to take emergency measures to meet ‘unexpectedly swollen demands’ for air supply from the army, and yet he wanted a second Dakota for his personal use – fitted with sound-proofing, sleeping-cabin and specially polished wings. In his April report on the command’s affairs, Park was recorded as telling Leese, on the subject of Dakotas: ‘After Rangoon [is captured], you can have one with gold knobs on.’ That was a treat Leese would be denied, because early in May he attempted to sack Slim, but was himself sacked and replaced by Slim in July.

It was with Leese in mind that Park wrote to the Director of Air Information, Eastern Air Command, on 27 April, enclosing comments by a visiting British journalist on the lack of publicity for air force achievements in South-East Asia. Greater publicity, said Park, would not only be deserved and a boost to morale, it would prevent the army from receiving ‘a disproportionate share of the credit which might serve to strengthen any move of theirs postwar to demand a separate Army Air Force.’ He drew attention in his April report to Slim’s Order of the Day (16 April) in which he had said: ‘Nor could there have been any victory at all without the constant ungrudging support of the Allied Air Forces. It is their victory as much as ours.’ Park wanted this tribute widely publicized. Otherwise, the postwar integrity of the air force would be jeopardized by a belief that the air was ancillary to the ground effort and that the direction of air warfare could therefore be undertaken by soldiers. And yet Park was by no means anti-army. On 7 May, for example, he wrote in praise of the excellent work of Air Formation Signals (AFS). They were army personnel and, as Park informed the Adjutant General in Delhi, they had ‘worked splendidly to provide, under the most difficult conditions, the landline communications upon which the efficient operation of the RAF depends.’

Mountbatten told Park on 8 June that he had heard from Portal that the War Office would not agree to giving Leese the acting rank of general. Portal would accede to Mountbatten’s request that Park be made an Air Chief Marshal if Mountbatten assured him that this was acceptable to the other Commanders-in-Chief. He had so assured Portal, urging him ‘most strongly’ to promote Park in July at the same time as the Burma awards were announced. Douglas Evill, however, prevailed upon Portal to change his mind. Linking Park’s promotion to the liberation of Burma, argued Evill, would be ‘unnecessarily provoking’ to the War Office, since he had had so little to do with it and certainly not as much as Leese. Evill therefore proposed that Slessor set about Park’s promotion as a routine affair. On 9 August Mountbatten signalled Park to tell him that his promotion, with effect from 1 August, would be announced on the 14th. Sufficient time had then elapsed, presumably, to ensure that it was not associated in the public mind with the liberation of Burma.6

The occupation of Rangoon on 3 May 1945 marked the end of the American commitment in Burma. Each air force would thereafter prosecute the war in neighbouring theatres. ‘For the Royal Air Force,’ wrote Park, ‘the offensive now headed down the Malay Peninsula to Singapore. For the USAAF, however, the route lay across the Himalayas to China.’ The period of integration between British and American forces in South-East Asia ‘had shown a very real spirit of close cooperation,’ Park thought, and he did all he could to foster it. On VE (Victory in Europe) Day, 8 May 1945, he was required to present an honorary CBE to Major-General Howard C. Davidson, head of the American Tenth Air Force and former head of the Strategic Air Force, Eastern Air Command. Park ensured an impressive turnout of senior army and navy officers, as well as RAF officers, and many other notables – Chinese, Dutch, Indian, British and American. He imported a pipe band by air from Cawnpore and found some Scottish pipers; he paraded three squadrons, arranged a guard of honour, required all personnel not on duty or parade to attend as spectators and encouraged the presence of several hundred civilians. The parade was mounted with a style and zest uncommon among senior British officers and greatly pleased the Americans, as it was intended to do.

Later in May, Stratemeyer wrote to Park about the ‘disintegration’ of Eastern Air Command, to take effect from 1 June. He wanted to withdraw all American personnel, except for one squadron and Park’s Senior Air Staff Officer (Brigadier-General John P. McConnell) who would stay with Park until the 21st. The American headquarters would remain at Hastings to represent American air interests in India and act as a ‘zone of communication’ for the China theatre. Park signalled Stratemeyer on 24 May to pay tribute to the work of his command since December 1943 in helping to obtain air supremacy in Burma, without which air supply would have been impossible. He emphasized that American transport squadrons had carried the greater part of the airlift in support of British land forces in Burma. Without them, ‘we could not have defeated the Japanese Army so rapidly and decisively in 1945.’7

Park wrote the next day to Air Marshal Alec Coryton, head of RAF Burma, to say that he had asked the Air Ministry to appoint Cecil Bouchier (his old friend from Battle of Britain days) to relieve Stanley Vincent as head of 221 Group. Park thought well of Vincent and his group, which shared with Slim’s army the honour of having defended India from the Japanese in 1944, but Vincent was in need of a rest and change of scene. The army had slackened its efforts in Burma after the fall of Rangoon and was making a long business of clearing up; this had affected 221 Group adversely, in Park’s opinion. He therefore wanted Coryton to mount ‘a real Jap-killing competition’ between squadrons and wings. They must divide the whole of Burma into search areas and comb them systematically on every day fit for flying. Too many ‘little yellow devils"were being allowed to escape into Malaya. Operation Zipper, a massive combined operation intended to liberate Malaya, was planned for August and very hard fighting was expected; every Japanese who escaped from Burma would make that fighting so much harder. Outside a small circle, no one yet knew of the atom bomb, and the war against Japan was thought likely to last at least another year. Park himself did not expect to be in Singapore before Christmas and thought Japan would not surrender before May 1946.

With Operation Zipper in mind, Park expressed alarm at the priority being given in London to the formation of Tiger Force, a British contribution to the bombing of Japan. The Americans had told him that because of a lack of airfields it would be impossible to redeploy part of the US Eighth Air Force in the Pacific; he was therefore certain that Tiger Force would not be deployed there either. On 6 June he reminded Portal of the many disappointments experienced by Mountbatten in the past owing to SEAC taking second place to other theatres. He was surprised to learn that the Air Ministry preferred Tiger Force to SEAC even though the invasion of Malaya had been approved by the Chiefs of Staff for execution before Tiger Force began to operate. Mountbatten believed that Tiger Force jeopardized Zipper and Park supported him, but the Air Ministry was unmoved. Agitation continued until early August, when the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought the war to an abrupt end.8

On 2 July Park wrote to Anthony Eden, the British Foreign Secretary. Eden’s son, Sergeant Simon Eden, had been navigator of a Dakota engaged on a routine air supply flight calling at various destinations in Burma. It had landed according to schedule at Myingyan and had left there for Akyab, but had not been heard from since 23 June. Park told Eden that it would be in friendly territory if it had made a forced landing. Communications in Burma were so bad that the crew might take a couple of weeks to reach a military or air base. There had been such cases and Park promised to send Eden a most immediate signal if he heard anything. Simon had just been recommended for a commission and Park would see that the recommendation was forwarded to the Air Ministry without delay if he turned up safely. But John Grandy, Simon’s CO, informed Park on 4 July that there was now little hope of finding the Dakota crew alive, and on the 17th Park informed Eden that the wreckage had been found with the remains of four bodies. ‘I can only ask you both to remember that your son died doing his duty manfully,’ Park wrote, ‘on an operational flight of vital importance to our land forces in Central Burma.’

Eden, meanwhile, had replied to Park’s first letter. It was a comfort, he said, to know how much had been done to try and find the boy and also to know the details of the flight. Park must have written another letter which has not survived because Eden continued: ‘I was so much interested in your account of your talk with Simon. You are right about the sense of humour and I do think that he has a full share of common sense. . . . Sometime I will tell you what he wrote to me after you had been to see him. He was very impressed.’

Almost thirty years later, Eden – then Lord Avon – wrote to Park’s son Ian to say how sorry he was to learn of his father’s death. Avon was on holiday with Grandy – ‘a close friend and admirer of your father’s’ – when he heard the news, and said he shared Grandy’s admiration. ‘I have, however, another and more personal reason for wishing to write to you. ... I have on my dressing-table at the present time a snapshot of your father with another officer and my son. Simon always wrote very warmly about your father, and I am convinced that in his judgment your father held a very special place.’9

On 25 July Park submitted to the Air Ministry a report on morale and discipline in his command. Personnel were ‘supremely confident’ he said, of their ability to finish the war quickly. There is, however, a strong and widespread feeling that the Home effort is not being maintained.’ South-East Asia had previously been the forgotten front, but now it was the unwanted front. Park had expected that after VE Day he would get the manpower needed to fill long-standing vacancies and relieve those who were ‘tour-expired’; he had also expected that there would be shipping available to bring the equipment necessary to improve living conditions. It should be realized, he added, that British rates of pay did not compare with American or Dominion scales. Prices in Ceylon and the larger Indian cities were high, demand exceeded supply and value for money was hard to find. Better amenities, entertainment, films, wireless sets and ‘good cigarettes’ were all needed. He emphasized that there was great sympathy in the RAF for the hardships endured by men of the Fourteenth Army. Their efforts against the Japanese – very tough fighters, met under the most trying conditions – were regarded as second to none and it was widely believed that people at home had never appreciated them.

Neither had they appreciated the efforts of airmen, in Park’s opinion. On 7 August he wrote to Air Marshal Sir Richard Peck at the Air Ministry to ask for his help in getting a really first-class writer of international reputation to come out and write the story of air power. The chance to emphasize as clearly as possible the fact that no navy or army could fight a major battle successfully until the air battle had been fought and won should not be missed.

The next day, he got from Mountbatten himself some of the recognition he sought for the achievements of air power. ‘No Army in history,’ said Mountbatten in a radio broadcast from London, ‘has even contemplated fighting its way through Burma from the north until now, not even in Staff College studies. The Japs came in the easy way and we pushed them out the hard way.’ To keep the troops supplied, Mountbatten had asked the air forces to fly at double the authorized rates per month. It has been by far the biggest lift of the war, ‘though heaven knows most other theatres had many more transport aircraft and they didn’t have the monsoon and the jungle to fight.’ At a press conference on 9 August, Mountbatten paid generous tribute to Park, ‘who has brought with him the fighting spirit which he showed in the Battle of Britain and the Battle of Malta.’ The campaign certainly turned round the Mountbatten-Slim axis. Men with little in common save ‘the power of commanding affection while communicating energy’, they har-nessed and drove the Allied forces to victory. However, the contribution of air power to the defeat of the Japanese in that theatre was crucial and Park’s part in directing it in the final stages was proficient and enthusiastic.

Japan’s unconditional surrender was announced at midnight on 14 August and Park, in a message to all ranks, stressed the tasks remaining. Tens of thousands of prisoners awaited release and needed food, clothing and medical attention. The RAF must also take part in the occupation of enemy-held territory and help to restore civilian law and order. The forward movement, he warned, would absorb shipping that might otherwise have been available to carry men home. At that time, the regions for which SEAC was responsible contained 128 million people, whose pent-up nationalist feelings were swiftly aroused; there were some 250 prison camps, containing 125,000 prisoners and, not least, there were 750,000 Japanese soldiers at large.

Hugh Saunders, a South African whom Park had known since Bertangles days, had by then arrived to command RAF Burma. Park wrote to him at the end of August to say that he hoped Saunders would be able to join him for the surrender ceremony at Singapore in September. This was the war’s last great occasion, marking the formal end of fighting against the Japanese in South-East Asia. Sadly, it did not mark the end of fighting there, even during the few remaining months of Park’s command. This fighting, together with the problems of winding down a vast military machine and creating its peacetime successor, tested Park as severely as any other task in his long career.10