The Battle of Britain: Meeting Them

Churchill now broke silence. There appear to be many aircraft coming in.’ As calmly, Park reassured him. There’ll be someone there to meet them.’

Richard Collier, Eagle Day

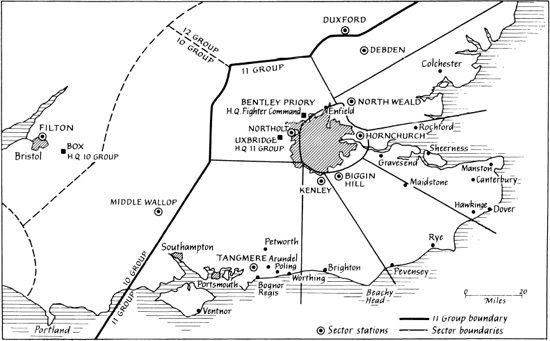

On 26 June, twelve days after the Germans entered Paris, Park urged Dowding to transfer the Debden sector from Leigh-Mallory’s care in 12 Group to 11 Group. The weight of attack on London and south-east England now likely from French bases was greater than he could resist without that reinforcement. For the same reason, he urged that Tangmere sector remain under his command and not be transferred to 10 Group, then forming for the defence of the south-west. Although information about raids was passed from one group to another, there was never the same coordination as when the interception fell entirely to one group. Dowding agreed: Park kept Tangmere and received Debden on 10 August.

From that date, Park controlled seven sectors and, as a rule, twenty-three squadrons. Leigh-Mallory commanded about fourteen squadrons distributed around six sectors to the rear of Park’s group and was responsible for the defence of the Midlands and East Anglia. Sir Quintín Brand commanded 10 Group (which became operational on 17 July) and had some ten squadrons in four sectors to protect South Wales and England west of Portsmouth. In the north lay 13 Group, under Richard Saul. He had up to fourteen squadrons (not all complete or fully operational) with which to guard Tyneside, Clydeside, Scapa Flow and Northern Ireland.

The underground operations room at Uxbridge, Park’s headquarters, had been completed in 1939. It was similar to that at Bentley Priory, except that the map showed only the group’s area, with some adjoining land and water, and the tote board showed only the group’s squadrons, plus any on loan from neighbouring groups. Park received his radar information from Bentley Priory and his visual or aural plots direct from tellers in Observer Corps groups in his area.

5: The Battle of Britain: Air Defence sectors

6: No. 11 Group in the Battle of Britain

All operations rooms were laid out to the same pattern. On a dais sat the senior controller, flanked by assistants and liaison officers. Each place on the dais was provided with communications to squadrons, to aircraft in the air and to all other units and headquarters to which messages needed to be sent. Wireless operators sat in cubicles behind the dais in contact with airborne fighters. Radio cross-bearings of sector aircraft were plotted and the results passed to the main operations room. The senior controller could see at a glance plots of hostile raids as well as the movements of his own fighters, the state of the local weather and the state of readiness of his squadrons. He could also see how much petrol and oxygen his airborne fighters had left.

As the battle progressed, Park showed remarkable speed in responding to changes in German tactics. Although the Luftwaffe held the initiative throughout, and Park was obliged to fight entirely on the defensive, he was never off balance for more than a few hours. His choices were rational and his means as effective as could be expected. He would not otherwise have retained his command, for Churchill himself visited Uxbridge several times and, as Park wrote, ‘never interfered with the conduct of operations’. It is unlikely that Churchill would have interfered directly whatever Park did, but he would certainly have sent Dowding a tart note had he not thought Park up to his job.

Like Dowding, Park believed that the squadron was the fighting unit. This belief underlay Fighter Command’s structure. From the moment that orders were given by group controllers to sector controllers, they were to be executed by squadrons ordered off singly, in pairs or in larger formations from adjacent stations. Once airborne, they were controlled from the ground, by direct contact with their sector controller, and guided towards incoming raiders. When squadrons operated together from different sectors, each remained under the control of its own sector. As soon as raiders were sighted, squadron commanders took charge and no further attempts were made to contact them from the ground until it was reported to the sector controllers that the action had ended.

Group controllers had to distinguish between major raids and feints and keep as many aircraft as possible ready for action. Major raids had to be met with ‘sufficient’ opposition (bearing in mind the limited resources) and aircraft should neither waste their fuel on mere patrol nor be caught on or near the ground. Several balances between likely alternatives had to be struck every day of the battle. The reward for successful guessing was to delay once more the penalty for unsuccessful guessing. Group controllers were at the heart of the defensive system. Within minutes of the appearance of incoming aircraft on the cathode ray tubes at the coastal radar stations, group controllers would see displayed on their operations tables all the information coming from Bentley Priory. It was mainly on the basis of this information that they decided what action to take.

That information was supplemented by radio traffic analysis, the use of direction-finding to pinpoint the location of Luftwaffe bases, prisoner interrogation and the examination of captured documents. The most famous intelligence source was the Ultra operation at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, where German radio signals that had been enciphered by an Enigma machine were intercepted and translated. Enigma provided Dowding with information about the Luftwaffe’s organization, order of battle and equipment. It was unable to tell him whether the RAF would outlast the Luftwaffe because it was silent on the losses and effective strengths of Luftwaffe units and the size of reserves, nor could it forecast changes in German methods and objectives because communications between Berlin and formations in France were by landlines. ‘For all his major decisions,’ concluded the official history of British Intelligence in the Second World War, Dowding ‘depended on his own strategic judgment’.

In the day-to-day fighting, however, Enigma provided Park with an increasing amount of intelligence about the timing, size and targets of particular raids, even if the intelligence often arrived too late to be of immediate operational value and the Luftwaffe frequently made last-minute changes of plan. Park also received precious information from many careless German pilots, who paid little heed to radio security. Such interceptions supplemented other signals, radar and reconnaissance intelligence to help him determine the composition of enemy formations, their likely targets, assembly points for returning home and routes to follow. Even so, the pace of events throughout the Battle of Britain was so rapid, the options available to the Luftwaffe so many and the disparity in numbers and combat experience between the rival air forces so great that Park’s daily judgments were crucial to the battle’s course.1

Park had presided over a conference of squadron commanders at Northolt on 14 June to discuss air fighting tactics. Everyone had agreed upon the need for squadrons detailed to work together to plan their tactics on the ground. They discussed the composition of formations at length: should squadrons be employed singly, in pairs or in larger groupings? Even before the Battle of Britain began, Park was familiar with the arguments for and against the use of ‘big wings’, arguments which became bitter late in 1940. Everyone also agreed that R/T discipline was poor and Park directed that ‘a brief but pungent’ instruction be drawn up to curtail needless chatter.

He then invited suggestions for the best method of separating German bombers from their escorts. He reminded everyone of the danger of dispersing fighter strength too widely and observed that anti-aircraft fire might prove valuable in breaking up formations. He invited criticism of arrangements made and facilities available for operating fighters. It was vital, he thought, to see that pilots got proper rest and relaxation and therefore ruled that not more than two squadrons be based at one sector station; a third should be moved to a satellite airfield. Finally, Park had reminded his squadron commanders of a principle which he would stress over and over again once the battle began: their aim, he said, was the destruction of enemy bombers and action against fighters was only a means to this end.

On the same day – 14 June – Park informed his sector commanders that the Luftwaffe would probably soon begin attacks on 11 Group aerodromes in an attempt to cripple the ground organization. Should these attacks succeed, the Germans would be able to dominate southern England and repeat the conditions that obtained in Poland. Everyone must understand, he emphasized, that there was no intention of evacuating to bases elsewhere. This would merely play into German hands by severely hampering squadron control and servicing. Eleven Group would continue to operate its fighters however intensive the attacks. While attacks were actually in progress, personnel not performing essential duties would take cover, but others would carry on servicing aircraft and manning ground defences. Before the battle began, then, the decision to defend coastal Sussex, Kent and Essex had been taken and Park wholeheartedly supported it. Some pilots in 1940, and some commentators since, thought it foolish to hold coastal bases. Some even advocated a complete withdrawal to bases north of London, outside the range of German fighters, where British fighters could gain operational height undisturbed before speeding south. In the event, Park’s pilots were often obliged to climb under their opponents and were therefore at a serious disadvantage.

Nevertheless, he believed it necessary to hold the foremost line. There had as yet been no daylight raids on British towns and villages and the reaction of their inhabitants could not be known. There were also important military and industrial targets in the south-east. Moreover, 11 Group’s withdrawal would have been interpreted by many as a sign of impending defeat, while the consequent flight from the area would have cleared the way for a German assault – by parachute, if not by sea. Although Park was deeply concerned to safeguard the lives of his pilots and ground crews, he recognized a greater need to defend every acre of England against whatever odds the Germans imposed. If the south-east were to be defended, it followed that Park must engage at odds, promptly, and maintain reserves to use as and when he recognized the development of a heavy attack. His watchwords were speedy challenge, repeatedly offered. The time needed to assemble large formations would have permitted German raiders to reach their targets unmolested, and those formations would have absorbed reserves needed to challenge other raids.

One of his most persistent instructions concerned the need to attack bombers head-on. They were vulnerable in front, he wrote: poorly armoured, lightly armed, flying in tight formations (without room to manoeuvre) and led by the best pilots. ‘Attack the ones in front,’ he urged. ‘If you shoot them down, the formation will break up in confusion. Then you can take your pick.’ Such attacks allowed the least time for accurate shooting, the danger of collision was high, fighters were exposed to coordinated fire from rear-gunners as they overshot and enemy escorts could be well placed to join in. For these reasons Dowding refused to approve head-on attacks as a standard tactic, but many brave and skilful pilots responded to Park’s exhortation. Myles Duke-Woolley was one who did and survived to recall the fighting:

I will say the old Hun certainly tried hard, but they did not like that head-on business. One could see the leader carrying on straight, but the followers wavering, drawing out sideways to the flanks, and in some cases just plain leaving the formation.

Such tactics would only serve in daylight, of course, but Park was also concerned throughout his time at Uxbridge with attempts to counter night attacks. On 14 June Wing Commander Vasse, of the Air Fighting Development Unit (formerly Establishment), sent him a paper on night-flying control. Sector controllers, he thought, must place pilots behind and below enemy aircraft and on the same course. It was no use putting them in the vicinity of raiders and asking them to search visually. Above all, controllers must not ask pilots for their positions. Having been directed all over the place, often above cloud and flying on instruments, they had no idea where they were. It was the controller’s job, said Vasse, to keep track of them. Park agreed and a few days later circulated Vasse’s paper together with new instructions of his own to all sectors. When enemy aircraft carried out a large number of night attacks, he wrote, group and sector plotting tables quickly became cluttered with tracks, making group control impracticable. When this happened, the group should order ‘sector control’ in the congested area and sectors would put up standing patrols when controlled interception became impossible.

Dowding remarked at the end of June that the use of searchlights provided the only hope of picking up enemy aircraft at night until AI [Airborne Interception, by radar] improved. Park thought so too, but on 25 July he wrote to Dowding about recent experience with single-engined fighters at night. Results had been ‘not less satisfactory’ than with the twin-engined Blenheim, which was too slow and the pilot’s field of vision too restricted. He recommended that three sections of each Blenheim squadron be re-equipped with single-engined night-fighters. He recognized the inconvenience, from the point of view of maintenance, of operating two types of aircraft in one squadron, but more interceptions would be made. He was told that the Beaufighter, a twin-engined machine specially designed for radar-controlled interception at night, would soon be available. Unfortunately, it suffered many teething problems and achieved little in Park’s time at Uxbridge.2

During July, the ‘Channel War’, like the Dunkirk evacuation, posed problems for Park that he could not solve. Whenever a convoy was at sea, the Luftwaffe attacked at its own convenience and obliged Park to mount a standing patrol overhead during daylight. At one time early in July, as many as seven coastal convoys were in passage around British coasts between Swanage in Dorset and the Firth of Forth: all open to attack and all difficult to defend, given the short range of British fighters and the brief warning provided by radar. Although unescorted bombers were easily driven away, tiring patrol work from primitive forward airfields continued day after day. Casualties caused by fatigue were already noticeable and Park became aware of a problem that plagued him until December – when to withdraw experienced but tired men from the front line and replace them with fresher pilots who were novices in the savage world of aerial combat.

Operations over water soon revealed the need for a properly organized system of rescuing ditched airmen. They were at first entirely dependent on ships which happened to be nearby. Specially equipped search aircraft and high-speed launches were needed as well as aids to help pilots stay afloat and mark their position until help arrived. In these respects, the Luftwaffe was better placed than the RAF. It had float planes for rescue work, combat aircraft carried inflatable rubber dinghies and aircrew were provided with fluorescine, a chemical which stained the sea bright green. By the end of July, Park and Vice-Admiral Ramsay at Dover had borrowed from the army some Lysander aircraft to work systematically with rescue launches and the use of fluorescine had been copied. Gradually, but not until long after the Battle of Britain was over, a comprehensive air-sea rescue organization was created in August 1941.

On 29 July 1940 Sholto Douglas signalled Fighter, Bomber and Coastal Commands to order strong counter-measures against E-boat bases, enemy coastal aerodromes and gun emplacements. These measures should be so planned as to hit aerodromes just after German aircraft had landed following attacks. Douglas Evill minuted Dowding about this signal next day, having discussed it with Park and Bottomley, the Senior Air Staff Officer of Bomber Command. E-boat bases could be attacked when reconnaissance reported that the boats were there, he said, but attacks on aerodromes were unlikely to be profitable because they were too well defended. Attack following a large raid would be particularly tricky. German activity over Calais was constant and it was impossible to tell when a large raid had actually begun until it moved out from the coast. By that time, it was within five minutes of Dover. From the moment such a raid became obvious until the moment it re-crossed the French coast was seldom more than thirty minutes. In order to catch enemy aircraft on the ground after their attack, bombers would have to be given executive orders as soon as an attack even seemed likely. They would need to be at fifteen minutes’ notice in order to reach their objectives in time and kept indefinitely at that notice.

As for Park, continued Evill, he would find it difficult straight after an attack to find enough fighters to cover a counter-offensive. He was using about six squadrons against large attacks and needed three more to cover his advanced landing-grounds while those six were refuelling and rearming. Finding three or four more to escort bombers would absorb his entire force. Park had pointed out, moreover, the difficulty of controlling and coordinating three or four squadrons hastily detailed for escort from different aerodromes. It would therefore be ‘unwise and probably impracticable’, concluded Evill, to attempt a counter-attack in strength. A deliberate attack at a chosen time, preceded by thorough study and reconnaissance of harbours or aerodromes, offered more fruitful prospects. The note of reality thus introduced by Evill, Bottomley and Park into Douglas’s orders was one that had to be repeated all too frequently during the summer and autumn of 1940.3

Evill wrote to Park on 6 September. The past month of intensive lighting had passed week by week through several distinct phases, he said, and it was obviously important that the authorities responsible for higher policy should be as fully informed as possible about this fighting. At present, Park’s headquarters was ‘carrying the whole force of the enemy attack’; in his sector and group operations rooms there was ‘experience and information not available elsewhere’ and Evill would therefore welcome a note on recent operations. What, he asked, have been the main features of the enemy dispositions and tactics from phase to phase? What effects have these had on the success of British squadrons in interception and combat? Did Park recommend any changes in organization? Evill knew that he was very busy and expected only a short report, but he would like it soon.

Park sent his report within a week. Evill, an intelligent and sensitive man, had guessed that Park, if asked tactfully, would do more to oblige than one could reasonably expect of someone carrying his present burden. Dowding thought it a good report and forwarded it to the Air Ministry with his comments on 22 September. He agreed with Park on the need to supplement the means available for reporting raids by using fighter reconnaissance aircraft to observe the composition of enemy formations during their approach and report direct to group headquarters. However, when Douglas minuted Cyril Newall, Chief of the Air Staff, on Park’s report and Dowding’s covering letter, his tone was critical throughout and in particular he seized upon the brevity with which Park discussed the problems of night-fighting. There had, however, been very little night-fighting prior to 10 September, when the report ended. Douglas, moreover, was usually the chairman of an Air Ministry committee specifically set up to consider night-fighting problems, but that committee never asked Park for his views.

The report covered the period from 8 August to 10 September and Park divided it into three phases. The first was from 8 to 18 August, the second from 19 August to 5 September and the third ‘which is now occupying all my Group’s attention by day and by night’ had begun on 6 September. In the first phase, the Germans had used massed formations of bombers escorted by fighters flying much higher. ‘These tactics,’ wrote Park, ‘were not very effective in protecting the bombers.’ Attacks on coastal targets in Kent were intended to attract British fighters and so clear the way for heavier attacks on ports and aerodromes on the south coast between Brighton and the isle of Portland Bill. Park’s main problem had been to identify the principal attack, as opposed to feints, bearing in mind ‘the very unreliable information received from the RDF stations after they had been heavily bombed.’ To counter attacks on coastal targets, it was necessary to keep most ‘readiness’ squadrons at forward aerodromes and group controllers had to be extremely vigilant to protect them from attack while grounded. Even in the first phase of the battle, Park had stated his cardinal principle: ‘to engage the enemy before he reached his coastal objective.’

His general plan had been to employ Spitfires to engage high-flying German fighters and to direct Hurricanes against bombers. Stern attacks worked well against fighters, but not against bombers, so Park had advised pilots ‘to practise deflection shots from quarter astern, also from above and from below against twin-engined bombers.’ Casualties were relatively higher than during the French campaign because of ‘the fitting of armour to enemy bombers’ and a shortage of ‘trained formation and section leaders’ in the British force. Even so, results had been satisfactory. He thought the proportion of enemy aircraft destroyed to British losses had been about four to one during the eleven days from 8 to 18 August.

In fact, it was less than two to one, although the Luftwaffe lost more than five times as many aircrew killed as the RAF during that time. Whatever the true figures, the defence had undoubtedly proved too good for the offence and a break of five days from intensive operations followed the Luftwaffe’s major effort made on 18 August. On no other day would either side suffer a greater number of aircraft put out of action, which is why the eminent historian Alfred Price nominated the 18th ‘the hardest day’ of the Battle of Britain.

The Luftwaffe should have concentrated on knocking out radar stations and Fighter Command’s coastal aerodromes, thus easing the way for subsequent penetration as far as London. Well directed attacks, boldly pressed home, would have wrecked the early-warning system. Sector aerodromes and dispersed aircraft could then have been attacked at leisure and landline communications disrupted. The Germans, in short, could have achieved aerial supremacy over south-east England despite Park’s skilful handling of the defence. He once told Johnnie Johnson, the top-scoring Allied fighter ace of the war, that he dreaded more than anything a persistent attack on his sector stations. He could not have intercepted successfully from ground readiness and standing patrols were no answer. There were plenty of aerodromes in south-east England that Park could have used, but they were not equipped to communicate direct with his headquarters. ‘Without signals,’ he said, ‘the only thing I commanded was my desk at Uxbridge.’

The attack on radar stations on 12 August showed what could be done. Dover, Pevensey and Rye were all put out of action, though emergency systems enabled them to resume reporting within six hours. They were difficult targets to destroy, but the Germans failed to realize that they were worth the effort. On this occasion, a large raid was built up (unseen by the Kent and Sussex radar stations) which hit the Isle of Wight hard and knocked out Ventnor radar station. Even in this crisis, Park remembered the German tactic of introducing new fighter formations to cover the withdrawal of a large raid. He therefore held back some fighters so that when Bf 109s were reported flying west near Beachy Head, he was able to intercept them and so prevent the situation over the Isle of Wight from getting worse.

Next day, 13 August, Park had good warning from radar that a big raid was approaching and responded with an effective blend of enterprise and caution. On his extreme left in Suffolk, he put up small formations over two aerodromes. At the same time, still on the left, he ordered up two Hurricane squadrons and a Spitfire squadron. These aircraft were divided between a convoy in the Thames estuary and forward aerodromes at Hawkinge and Manston. On the right, he ordered a section of Tangmere’s Hurricanes to patrol their base and the rest of the squadron to patrol a line over west Sussex from Arundel to Petworth. He also ordered a squadron of Northolt Hurricanes to take up a position over Canterbury from where he could switch them in any desired direction. Finally, he reinforced his left with most of a Spitfire squadron from Kenley and his right with another Tangmere squadron. These dispositions left him with about half his Hurricanes and two-thirds of his Spitfires uncommitted, a fair provision for contingencies in view of the large forces at the Luftwaffe’s disposal. As the Germans reached the Sussex coast, in two escorted formations, Park chose the right moment to send in the Hurricanes waiting over Canterbury. One formation was intercepted near Bognor, the other near Worthing by one of the Tangmere squadrons; neither reached its target.

The effective resistance offered in south-east England led Goring, head of the Luftwaffe, to believe that fighters must have been withdrawn in substantial numbers from the north. Therefore, on 15 August large raids were sent from bases in Norway and Denmark towards the north-east. They were beaten back and their failure was vital. Had they succeeded, Dowding’s defences would have been dangerously stretched thereafter. When the crisis came early in September, he could not have concentrated his dwindling reserve of trained pilots in Park’s command. On the other hand, he could not know that the attempt on the north would not be repeated and was obliged to retain a strong force there and in the Midlands. It was a matter of seeking a balance between real and potential dangers. As it happened, some pilots in 12 Group felt themselves underemployed and it was there that the notorious ‘big wings’ controversy originated.

On 19 August Park summed up the lessons of recent fighting in one of his numerous instructions to his controllers. He was convinced, he wrote, that the Luftwaffe could be thwarted as long as sector aerodromes remained in service, inflicting steady losses, and the temptation to swap fighter for fighter was resisted. But too many pilots were being lost over the sea in hot pursuit of retreating aircraft. Such losses grieved Park more than any others: retreating Germans were beaten Germans, at least for that day, and if they could be forced to retreat every day it mattered little to him that their lives and machines were spared, because Britain’s defences grew stronger every day. The battle would be won if Fighter Command remained in being until autumn weather prevented a seaborne invasion. And yet, on the very next day, Park signalled Hornchurch to commend the ‘fine offensive spirit of the single pilot of No. 54 Squadron who chased nine He 113s [actually Bf 109s] across to France this afternoon.’ He went on to ask everyone at Hornchurch, and at all his other stations, to beware of the German practice of putting up strong fighter patrols over the Straits of Dover to protect aircraft returning from raids. It is a revealing signal. He had just given strict orders that this chasing was not to be done. When it was, he made the best of it, mixing praise for the pilot’s courage with advice on the dangers involved, and avoiding a heavy rebuke. He had himself been a fighter pilot and could still handle the latest types; he understood that the young men who fought in them must be led rather than driven.4

In the second phase of the battle (19 August to 5 September in Park’s reckoning), the Luftwaffe turned their attacks from coastal shipping and ports to inland aerodromes, aircraft factories, industrial targets and ‘areas which could only be classified as residential.’ Just as Park had taken stock during the five-day lull following the ‘hardest day’ on 18 August, so too had the Germans. From 24 August smaller bomber formations were employed, escorted by fighters ordered to stay close to their charges. These tactics made it difficult for Park’s pilots to obey his orders to attack bombers and avoid fighters. Worse, the use of a larger number of smaller formations impaired the radar warning: plots were more complicated and British fighters liable to be dispersed in several directions, leaving gaps for a carefully prepared penetration. As the Luftwaffe raided further inland, Park called upon 10 and 12 Groups to provide cover for aerodromes and aircraft factories near London. He was thus able to meet the enemy further forward in greater strength, while his neighbours protected vital targets behind his fighters.

On 25 August he drew his controllers’ attention to a new German tactic. Bombers had recently been coming inland escorted by fighters flying at the same level. By detailing some British fighters to go high, to engage escorts which turned out not to be there, controllers were permitting these bombers an easier run. He was acutely aware that his pilots were anxious to get as high as possible before engaging the enemy and that single squadrons had sometimes faced large formations. Both problems were exacerbated by cloud and consequent errors in reports from the Observer Corps. He therefore ordered formation leaders on 26 August to report the approximate strength of enemy bombers and fighters, also their height and position, as soon as they sighted them. Such reports, given promptly, would allow Park to see to appropriate reinforcement.

It was also on 26 August that Park reminded Dowding of a report he had produced on 8 July which had drawn attention to the fact that the heaviest casualties had been suffered by reinforcing squadrons from the north, which had been formed only after the outbreak of war. This, he said, was still the situation. He asked that only highly trained and experienced squadrons be sent south to exchange with depleted squadrons. He had compared the fortunes of three 13 Group and two 12 Group squadrons transferred to his command at various dates in July and August. The former were credited with forty-three aircraft destroyed at a cost of two pilots missing and two wounded; the latter had brought down only seventeen aircraft and lost thirteen pilots in exchange. Park attributed this pronounced disparity to the fact that Richard Saul of 13 Group always chose experienced units for service in the south whereas Leigh-Mallory did not.

‘Contrary to general belief and official reports,’ wrote Park in September, ‘the enemy’s bombing attacks by day did extensive damage to five of our forward aerodromes, and also to six of our seven sector stations.’ Mansion and Lympne were unfit for operations ‘on several occasions for days’ and Biggin Hill was so severely damaged that for over a week it could operate only one squadron. Had the Luftwaffe continued to attack these sectors, ‘the fighter defences of London would have been in a parlous state during the last critical phase when heavy attacks have been directed against the capital.’ Sector operations rooms suffered both from direct hits and damage to landlines. They all had to use emergency rooms, though these were too small and poorly equipped to cope with the normal control of three squadrons per sector.

In Park’s view, the Air Ministry’s arrangements for labour and materials to repair damage to fighter aerodromes were ‘absolutely inadequate’ despite ‘numerous letters and signals during the past four weeks.’ On his own initiative, he employed whole battalions of soldiers to fill in bomb craters and clear away rubble. Predictably, the Air Ministry objected to this unofficial arrangement and the incident still rankled with Park twenty-five years later: ‘I was severely criticized by the Air Ministry at the time for accepting Army assistance. Had my fighter aerodromes been put out of action, the German Air Force would have won the battle by 15 September 1940.’

When forwarding Park’s report to the Air Ministry on 22 September, Dowding claimed that only two aerodromes were unfit for flying for more than a few hours and that the works organization coped well enough. Did Park exaggerate the damage done and the weakness of that organization? His criticisms, so forcefully expressed, caused offence in the Air Ministry, weakening Park’s standing there and making it easier for Douglas to win support for his conviction that Park should be replaced. But Dowding had come round to Park’s opinion a year later, when he submitted his own account of the battle to the Air Ministry. It must be ‘definitely recorded’, he wrote, that the damage done was serious and had been generally underestimated.

During the eighteen days of Park’s second phase (19 August to 5 September), the Luftwaffe lost more than three aircraft for every two British aircraft destroyed and nearly five times as many German airmen were killed. Statistically, Fighter Command was doing well. Not only were Luftwaffe losses much heavier, but British fighter production and repair made good most of the command’s losses. At that rate of exchange, however, the command would collapse while the Luftwaffe was still in being. Quite apart from the 106 British pilots killed, nearly as many were badly wounded out of a total strength of about one thousand and the output of the training system failed to match the casualties suffered.

Park issued a terse instruction to his controllers on 7 September, pointing out that on one occasion the previous day only seven out of eighteen squadrons despatched had intercepted the enemy. Some controllers were ordering squadrons intended to engage bombers to patrol too high. When group control ordered a squadron to 16,000 feet, its sector controller added another couple of thousand and the squadron did the same, hoping to avoid danger from above. The result was that bombers were getting through every day at 15,000 feet. In fact, said Park, most of them were intercepted only after bombing, on their way home. The low interception rate worried him because Dowding had told him that morning that invasion was officially considered ‘imminent’. Park made his dispositions for the day with continuing attacks on sector stations in mind, ordering squadrons to patrol well back from the coast in anticipation of another assault on battered aerodromes. He then left Uxbridge to confer with Dowding at Bentley Priory. Unfortunately, these dispositions helped clear the route to London for the Germans, who launched a massive attack upon the capital late that afternoon.5

Only seven men were present at the meeting: Dowding, Park, Evill and Nicholl of Fighter Command, Douglas and a group captain from the Air Ministry and an NCO shorthand-typist to take the minutes. Dowding explained that he had convened the meeting in order to decide the steps to be taken to ‘go downhill’, if necessary, in the most economical way to permit a rapid climb back. He assumed a situation arising in which efforts to keep fully trained and equipped squadrons in the battle would fail. His policy had been to concentrate a large number of squadrons in the south-east, with stations on the fringe brought in at Park’s request on the worst days. As squadrons became tired, these were taken out of the line and fresh ones put in from one of the three reinforcing groups. If the present scale of attack continued, however, this replacement policy would become impossible. So Dowding wanted to make a plan now to cover what he would do in that event. Although he would not amalgamate squadrons if he could help it, he might have to rob rear squadrons of their operational pilots to make up shortages. It seemed that enough pilots would be available, but the problem was to turn them into combat pilots. The Germans must not be allowed to know how hard hit the command was and Dowding would therefore keep 11 Group up to its present numbers, come what may, but he could not increase the number of squadrons in that group.

Douglas asked if he were not being pessimistic in talking about going downhill. Dowding disagreed, emphatically. Park, he said, was at this moment calling for reinforcements to five squadrons which had themselves just come into the line. But there was no shortage of pilots, Douglas replied, and when Dowding began to explain the skills needed of a fighter pilot, he assured him that the command would be kept up to strength. Douglas’s lack of comprehension baffled Dowding, but Evill now intervened. Total casualties for the four weeks ending 4 September were 348, he said, and since the three Operational Training Units had turned out only 280 fighter pilots in that period, a net loss of 68 resulted, quite apart from accidents and illness.

For the moment, Douglas fell silent and Park remarked that casualty figures in 11 Group were nearly 100 a week and that there was indeed a pilot shortage. That day, he said, nine squadrons had started with fewer than fifteen pilots and the previous day squadrons had been put together and sent out as composite units. Dowding interrupted him. ‘You must realize,’ he said, speaking directly to Douglas, ‘that we are going downhill.’ After a pause, Park continued. It was better to have twenty-one squadrons with no fewer than twenty-one pilots in each than to have a greater number of under-strength squadrons in 11 Group. Some squadrons were doing fifty hours’ flying a day and while they were flying – and fighting – their aerodromes were being bombed; while they were on the ground, they could not get proper meals and rest because of the disorganization and night raids.

Douglas suggested opening another OTU. This would be done if casualties remained heavy, although if the whole of August was considered, the command’s strength was being maintained. Dowding pointed out that the true picture only emerged from the figures after 8 August, when large-scale attacks had begun. He had to assume that present scales of attack – and casualties – would continue. Another OTU, repeated Douglas, would ensure that pilot strength was maintained. But to be effective, Evill interjected, it would need to be in action very quickly; and, added Dowding, it would itself be a drain on the command for personnel.

Park then described his scheme of sector training flights. They had been needed, he said, because OTU pilots were unfit to fight until they received extra training. But training flights had now been cancelled because all experienced pilots were needed for fighting and all stations were dispersed because of bombing. He suggested that pilots should go from their OTUs straight to squadrons in the north for extra training and that squadrons in the south should receive only fully trained men from the north to fill their gaps. Dowding argued that he must always have some fresh operational squadrons to exchange with 11 Group’s most tired squadrons. The two schemes could run parallel, replied Park. His idea of importing pilots, rather than whole squadrons, would only take effect when a squadron’s strength fell to fifteen pilots. Dowding agreed.

The next day, 8 September, Nicholl informed the group commanders that all squadrons had been divided into three classes. Class A were those in 11 Group, to be maintained at a minimum strength of sixteen operational pilots. Some squadrons in 10 and 12 Groups were also designated Class A, but their pilot strength (likewise a minimum of sixteen) might be operational or not. Class B squadrons might include up to six non-operational pilots in their quota of sixteen and Class C squadrons would retain at least three operational pilots. Command Headquarters would inform 10, 12 and 13 Groups daily of the number of pilots required of them for allotment to 11 Group. Evill wrote to Douglas on the 9th, enclosing a copy of this letter.

Douglas replied on the 14th. The draft minutes of the conference reminded him, he said, of a music-hall turn between two knock-about comedians in which one, usually called ‘Mutt’, asked foolish questions. He appeared to be cast in that role in these minutes, he said, claiming that they misrepresented him. ‘However, life is too strenuous in these days to bother about the wording of minutes,’ he continued. Evill answered the same day, politely rejecting Douglas’s charge of minute-faking. They were, he said, in almost exactly the words recorded at the time by the NCO shorthand-typist. He also rejected Douglas’s argument that there were too many Class C squadrons. They might each have to produce five operational pilots per week, said Evill, as well as perform their own operational tasks.

Park had long shared Dowding’s opinion that Douglas was a man of limited capacity. They believed that their plans for making the best use of available resources were sound. Evill and Nicholl, experienced and able officers, fully supported them. Dowding and Park had neither the taste nor the time for Air Ministry politics, least of all during a major crisis, and consequently they quite failed to realize that their unconcealed contempt for Douglas’s contribution to the meeting on 7 September placed them in grave danger. Douglas attended no more meetings at Dowding’s headquarters, away from his home ground in the Air Ministry, where supporters were plentiful and he could usually act as chairman. The next meeting which Dowding, Park and Douglas all attended took place six weeks later – at the Air Ministry, with Douglas in the chair – and he did not then find life too strenuous to bother about the wording of minutes, as Park learned to his cost.

Douglas never accepted a distinction between simple flying ability and vital fighting experience. On 31 October, for example, he would write that the pilot position had undergone a ‘kaleidoscopic change’ in the last week or two: ‘in the case of Fighter Command we are actually faced with a surplus.’ Two days later, Evill reported more realistically to Dowding on the pilot position as at 31 October. At the end of July, he wrote, there had been sixty-two squadrons and 1,046 operational pilots; at the end of October, there were sixty-six and a half squadrons, but only 1,042 operational pilots. Total wastage in those three months was 1,151 pilots: twenty-five every two days. During October, 231 pilots had been lost to the command, during a month when the weather had been exceptionally bad and combat losses as low as could possibly be assumed for any winter month. The command, Evill concluded, was ‘at about the lowest ebb in operational pilots’ at which it could function. Early in 1941, the Air Ministry would publish an account of the battle in which it claimed that Fighter Command’s squadrons were stronger at the end than at the beginning. Dowding and Park rejected that claim, vigorously and publicly.6

At about 5 p.m. on 7 September, while Park was still in conference at Bentley Priory, the Luftwaffe launched a massive daylight attack on London. During the next hour and a half, more than 300 bombers (escorted by 600 fighters) set fire to docks, oil tanks and warehouses along the banks of the Thames east of the city. They also blasted numerous densely populated streets. Park’s senior controller, John Willoughby de Broke, said later that Park was adept at sensing German intentions. He would let his controllers set the stage and then make decisions which could only be based on instinct or experience. Unfortunately, that afternoon he was not, for once, in his operations room. The very fact that the Germans chose a new target, one not hitherto attacked in daylight, contributed to the surprise achieved. Although the eventual challenge was vigorous, costing the Luftwaffe more than sixty aircraft destroyed or damaged, London was hit hard and Fighter Command lost twenty-four pilots killed or injured.

Park managed to reach Uxbridge shortly before the raid ended and, after a hasty discussion with his controllers about their handling of the fighters in his absence, left for Northolt, where he kept his Hurricane. From there, he flew over the blazing city to see for himself the extent of the disaster. Appalled by the sight of so many fires raging out of control, he reflected that the switch of targets would not be just for a single day or even a week and that he would have time to repair his control systems and so maintain an effective daylight challenge to enemy attack. He did not fear either a civilian panic or unmanageable and intolerable casualties in consequence of the new German policy, and yet Fighter Command was helpless at night. This was graphically demonstrated that very night. By 8.30 p.m., not long after Park landed, the Luftwaffe had returned. For the next seven hours, wave after wave of bombers flew over London, finding fresh targets in the light of the fires started by their comrades in daylight. They bombed at their leisure, unhindered either by anti-aircraft fire (of which there was little and that ill-directed) or by night-fighters (of which there were few and those ill-equipped).

In Park’s mind, 7 September was always the turning point. Three years later, he flew to London from Malta and gave his first press interview on the Battle of Britain. He explained how close the Germans came to victory and how they threw it away by switching their main attack to London. In 1945 he broadcast from his headquarters in Singapore on the fifth anniversary of the battle, an anniversary by then established as falling on 15 September. Park still regarded the crucial moment as the change of target eight days earlier. Then and later he said that he would never forget the courage of his outnumbered pilots. Their morale was so high, he thought, because they believed they had done well at Dunkirk. They believed also that persistent opposition would eventually discourage the Luftwaffe and they knew that, in any case, they had no choice. It was common knowledge that numerous barges were being assembled in enemy ports and that the British Army was insufficiently equipped to resist German soldiers should they get ashore in force. In September 1949 Park claimed that on the day when the invasion scare was at its height, 7 September, he was ordered by the Air Ministry to prepare to demolish every aerodrome in south-east England. He refused. Resistance, he said, was impossible without them and he was determined to resist to the end. The effect on morale of the mere issue of such an order would be wholly bad. Churchill himself telephoned Park at Uxbridge that day to tell him of the invasion alert. He had not seemed particularly perturbed and neither was Park. Provided that his fighter force could still be controlled from the ground, he did not fear an invasion attempt because he believed that the German fighters could be held off by part of his force, leaving the rest free to shoot down bombers and transport aircraft at will.7

Park completed his report on the third phase of the battle (6 September to 31 October) on 7 November. He instructed his sector controllers on 10 September to employ squadrons in pairs: they must not be ‘flung into battle singly to engage greatly superior numbers.’ Having seen for himself that some squadrons still flew in close v-shaped formations of three aircraft, he ordered them to fly in loose, line-abreast formations of four aircraft. Experience had shown that the latter formation allowed pilots to keep a much greater area of sky in constant view and so be able to offer each other quicker support. Whenever squadrons split up in action, he wrote, pilots should try to keep in pairs because a solitary pilot could not guard his own tail and sooner or later must be shot down.

His squadrons were now working under extreme difficulty because of the heavy damage caused earlier to installations and landlines. Sectors were still controlling squadrons from emergency operations rooms, and telephone links between group, sector and Observer Corps centres were unreliable. The wide dispersal of squadrons to satellite airfields and the damage to station organization caused a marked slowing down in refuelling, re-arming and maintenance of aircraft and equipment. The extra motor transport required by dispersal had not been received and internal telephone links at sector stations were often broken. Luckily, attacks on aerodromes were now carried out mainly at night or at high level by day and caused little additional damage. Fully equipped alternative operations rooms, located well away from sector aerodromes, were being brought into use throughout Park’s group during September.

Since August, he had been using single Spitfires to supplement radar and visual information by shadowing raids and reporting their movements. These ‘Jim Crows’, as they were known, provided valuable information for sector controllers, but it could not reach group controllers in time to help them. Too few machines fitted with VHF Radio Telephone equipment were available. At length, a special unit was formed at Gravesend and an R/T station set up at Uxbridge to receive direct reports from aircraft on patrol. No sooner had the unit begun work than the Air Ministry moved it to make room for night-fighters. It went to West Mailing just in time to be grounded by heavy rain. Despite these setbacks, the unit supplied information, especially about high-flying intruders, that was beyond the capacity of radar or the Observer Corps. After four of its unarmed Spitfires were shot down in the first ten days of October, Park urged the Air Ministry to double its strength and provide him with interceptors capable of protecting ‘Jim Crows’. Although Dowding supported him, nothing had been done by December.

During the morning of 15 September Park received a visit from Churchill, accompanied by his wife and one of his private secretaries. He had no wish to disturb anyone, he said, but as he happened to be passing, he thought he would call in to see if anything was up. If not, ‘I’ll just sit in the car and do my homework.’ Naturally, Park welcomed the Prime Minister and his companions and escorted them down to the bomb-proof operations room, fifty feet below ground level. Churchill sensed that something important might happen that day. (Park’s wife had the same sense: when he apologized at breakfast for forgetting that 15 September was her birthday, she replied that a good bag of German aircraft would be an excellent present.) Once they were in the operations room, Park tactfully explained to Churchill – not for the first time – that the air conditioning could not cope with cigar smoke. As the day’s dramatic events unfolded, the Prime Minister was therefore obliged to observe them with no better consolation than a dead cigar between his teeth. He had met Park several times and regarded him highly, recognizing (as he wrote after the war) that his was the group

on which our fate largely depended. From the beginning of Dunkirk all the daylight actions in the South of England had already been conducted by him, and all his arrangements and apparatus had been brought to the highest perfection.

Although Dowding exercised supreme command, ‘the actual handling of the directions of the squadrons,’ Churchill continued, ‘was wisely left to 11 Group.’

Soon after the visitors were seated in the ‘dress circle’ of the operations room, Park received a radar report of forty-plus aircraft over Dieppe, but no height was given. Then came another report of forty-plus in the same area and several squadrons were despatched to climb south-east of London. More squadrons were alerted to ‘Stand By’ (pilots in cockpits, ready for immediate take-off) and the remainder were ordered to ‘Readiness’ (take-off within five minutes). Having decided that a major attack was intended, Park had to guess its most likely targets, for his squadrons could not be everywhere. As always, he would concentrate on engaging bombers before they reached those targets, seeking to break their formations and cause them to jettison their loads into the sea or over open country.

Churchill remembered Park walking up and down behind the map table, ‘watching with vigilant eye every move in the game . . . and only occasionally intervening with some decisive order, usually to reinforce a threatened area.’ Churchill now broke silence. ‘There appear to be many aircraft coming in.’ As calmly, Park reassured him. ‘There’ll be someone there to meet them.’ Soon all his squadrons were committed and Churchill heard him call Dowding to ask for three squadrons from 12 Group to be placed at his disposal in case of another attack. He noticed Park’s anxiety and asked: ‘What other reserves have we?’ ‘There are none,’ Park replied. Exactly four months earlier, at the Quai d’Orsay in Paris, Churchill had put the same question to General Gamelin, Commander in Chief of the Allied army in the West, and had received the same answer. However, Park had a far stronger grasp of his problems and resources than that unfortunate Frenchman. Nevertheless, as Park wrote later, Churchill ‘looked grave’. In fact, his squadrons were often wholly committed and Park’s anxiety on this occasion was exacerbated by wondering just where and when the reinforcements from 12 Group would turn up.

Churchill asked if Park could yet judge the results of his pilots’ efforts. He answered candidly that he was not satisfied that the maximum number of raiders had been intercepted. It was already evident, however, that the Germans had caused serious damage. By this date, Park had learned to cope with one of a commander’s heaviest burdens, the burden of waiting: waiting to learn if his dispositions had been correct or if he had made an error that would cost the lives of his own men or if he had failed to seize an opportunity to harm the enemy.

While Park and Churchill wondered and waited, the Germans had made their greatest bid for victory in daylight. The attack on London was made in two stages, one in the late morning and the other after an interval of about two hours. If the Luftwaffe were to use its full bomber force, maximum fighter protection would have to be provided all the way out and home. Consequently, there was no scope for feints which would consume fuel and reduce both the number and endurance of escorts. The German shortage of fighters compelled the division of the attack, so that some could be used twice and so that the second attack could, with luck, catch many of Park’s fighters on the ground, re-arming and refuelling.

Masses of German aircraft were observed by radar about 10.30 a.m., but they remained on the French side of the Channel. Park and his controllers therefore had time to work out a sequence of action and ground defences were fully alerted. Only then, almost as if they were waiting for these preparations to be completed, did the Germans advance. The attack proved so straightforward that Park’s fighters were fed into battle as and when it suited him. He employed eleven squadrons and then asked for help. Brand sent one squadron, Leigh-Mallory a wing of five squadrons. With admirable judgment, Park threw in five more of his own in time to meet the enemy over Rochester, after five of his original eleven had engaged farther forward. He had asked Leigh-Mallory’s wing to guard his aerodromes north of London. Instead, it flew straight to London and helped to break up the German formation. Bombs were scattered at random and as the raiders turned for home, they found four of Park’s squadrons waiting for them over Kent and Sussex.

After a welcome lull the Germans launched their second attack. The clouds had become heavier, the radar warning was shorter, Park’s fighters were later off the ground and the combat was more intense. As before, Leigh-Mallory contributed a wing of five squadrons and they, together with two of Brand’s squadrons, gave an excellent account of themselves over London, although Park’s pilots intercepted two of the three principal German formations before they reached the capital. Once turned, they were hotly engaged, as the first wave had been, over Kent and Sussex.

Two days later, observing that air superiority had not been attained, Hitler postponed his invasion ‘until further notice’. In the opinion of the official history, ‘the decisive factor was the series of actions fought by Air Vice-Marshal Park on the 15th of that month.’ But this was not apparent at the time, wrote Churchill, ‘nor could we tell whether even heavier attacks were not to be expected nor how long they would go on.’ Visiting Park again a few days later, he got the distinct impression ‘that a break in the weather would no longer be regarded as a misfortune.’ The threat of invasion remained real for weeks. An analysis of decrypted Enigma signals revealed on 16 October that ‘invasion preparations are actively proceeding or indeed becoming intensified’ and some date after the 19th was considered likely. The first decrypt to suggest that invasion had been postponed appeared on the 27th and it was not until 5 November that Churchill felt able to tell the House of Commons that ‘all these anxious months, when we stood alone and the whole world wondered, have passed safely away’; invasion was no longer an imminent danger.

Park had issued orders on 18 September to deal with an invasion attempt. His fighters would protect naval forces and bases, cover operations by Bomber and Coastal Commands, distract dive-bombers from attack on ships engaging enemy vessels and destroy enemy aircraft carrying troops or tanks. They would attack barges and landing craft and protect British troops from dive-bombers. Army and RAF personnel would jointly defend forward aerodromes. Demolition of installations and withdrawal would take place only as a last resort, ‘pending the arrival of Army mobile forces, when the aerodromes will be immediately recaptured’. As for inland aerodromes, they were to be held ‘at all costs and not evacuated’. Group control would be maintained as long as telephone links with sector operations rooms were intact. Should group control become impossible, sector commanders would take charge. Should sector control fail, senior officers would act on their own initiative. The invasion would be defeated in seventy-two hours at most, but during that time pilots and ground crews must expect a hard time.8

The great increase in the number of enemy fighters employed late in September and the onset of cloudy weather made the task of obtaining accurate information about the composition of raids more difficult than ever. It was practically impossible to distinguish fighters from bombers when operating at high altitude and yet it was necessary to do so. Otherwise, fighter sweeps – which were not attacked – would turn out to include a large proportion of bombers. Park’s high-level reconnaissance patrols did what they could to determine the composition of raids, but from 21 September he was obliged to resort to wasteful and exhausting standing patrols as well.

Dowding, in his comments of 15 November on Park’s report, drew particular attention to the fact that standing patrols had been resumed. He noticed a tendency to think that the danger from daylight attacks had passed and that chances could be taken in south-east England in order to strengthen forces elsewhere, at home and abroad. But the higher state of readiness now required, and the need for keeping patrols actually in the air before the start of an attack, meant that Park’s squadrons were under severe strain even though their actual losses were low.

The need for long patrols at high altitude made Park acutely aware that some pilots were simply not fit enough for this work. He was therefore keen to see that as many as possible were released for exercise and recreation whenever bad weather ruled out flying. He wanted more facilities, equipment and transport for them, also regular hot meals and more comfortable accommodation at dispersal points. Those in the London area should be billeted off their aerodromes in order to get undisturbed sleep. Regular ‘guest’ nights should be reintroduced and the provision of ‘string bands, in order to remove some of the drabness of the present war’ would be well worth the effort.

Park was conscious of the need to keep pilots amused and comfortable as well as fit, especially during the coming winter when bad weather and long hours of darkness would curtail flying, but he was also conscious of the fact that too many were novices both as pilots and as fighters. Many squadrons, he complained, being quite untrained in defensive tactics, were completely broken up by inferior numbers when attacked from above. They failed to make intelligent use of cloud and simply got lost in it, they were unable to conserve their oxygen or to maintain a good rate of climb. Some squadron and flight commanders were too old and staid for combat. The RFC lesson, he wrote, that peacetime qualifications for promotion – age and seniority – were irrelevant for combat pilots had to be learned again. Early in October a check revealed that the average age of squadron commanders was nearly thirty and Park was determined to move ‘old and tired’ men to ground duties or flying training and promote younger men before the ‘spring offensive’ of 1941.9

On 26 September Douglas informed Dowding that on the afternoon of the 24th twelve Blenheims of Bomber Command had been sent to attack minesweepers in the Channel. Fighter cover had been asked for, but had apparently failed to make contact with the Blenheims. Douglas wanted to know why. On the morning of the 24th, he continued, a single Anson of Coastal Command had been sent to attack E-boats and had itself been attacked by enemy aircraft. Had fighter escort been provided? If not, why not? Douglas did not ask Coastal Command why a single, vulnerable Anson had been used on such a dangerous mission.

Evill investigated both incidents at Dowding’s request. During a heavy raid on the 24th, he reported, instructions came from Douglas for fighter protection of an operation he was mounting involving both Bomber and Coastal Commands. The latter refused to take part, but Bomber Command agreed to go ahead. Although Park was very busy, three squadrons were sent to the right place at the right time. Only one pilot, however, was able to attack when German fighters dived on the Blenheims. Evill thought this illustrated the weakness of a mass of fighters tied at low altitude to direct support of slow-flying bombers. Many German fighter pilots would have agreed heartily and Douglas himself would eventually grasp the point, during 1941. As for the Anson affair, Evill regarded it as ‘an enterprise whose value may perhaps be questioned.’ The request for an escort, which failed to find it, had come from Stevenson, Director of Home Operations.

In his reply to Douglas, Dowding observed that ‘the arrangements made by No. 11 Group were all and possibly more than might have been expected of them under the circumstances.’ Douglas, abandoning his usual peremptory manner for the moment, kept silent. Portal, however, did not. Then head of Bomber Command, he wrote on 6 October to inform Dowding that he entirely appreciated the difficulty of coordinating bombers and fighters in busy times and emphasized the Very amicable relations’ between No. 2 (Bomber) Group and Park’s group, adding that he was unaware of the reason for Douglas’s signal of 26 September since neither he nor the commander of 2 Group had complained about the escort provided for the Blenheims. Both Douglas and Stevenson had the duty of scrutinizing the conduct of Fighter Command, but on this as on other occasions that scrutiny lapsed into dangerous interference.10

Until the end of September, Park was confident that his fighters were superior to their opponents. During October, however, in fighting at great heights – above 25,000 feet – he thought the Germans Vastly superior’ because their two-stage superchargers maintained higher engine power. The Mark II versions of the Spitfire and Hurricane were not the answer, in his opinion. Fighters capable of at least 400 m.p.h. with a ceiling of at least 40,000 feet were needed. They also needed heavier armament. A combination of two cannons and four machine-guns would be ideal, he thought: cannons for a more destructive blow against bombers, at the expense of a rapid rate of fire, and machine-guns to deal with fighters, when quick bursts were essential. He wanted more attention paid to improving cockpit heating and preventing air leaks, because at high altitude the smallest leak had a paralysing effect if it played upon any part of the body. In an attempt to counter intense cold, pilots were wearing thick, heavy clothing, which made it difficult for them to respond quickly to an emergency.

Park would have left the command before these matters were attended to, but progress was made in October in re-equipping aircraft with VHF R/T equipment. This made it possible, he explained, for squadrons to operate on separate frequencies when detailed to separate tasks or to operate on a common frequency when working as pairs or in larger units. He reminded command headquarters on 5 November that each sector station in his group would soon have two day squadrons equipped with VHF, but this would leave one squadron on HF at six stations. While one was on HF, the whole system must be retained, employing many personnel and landlines. Operational flexibility, he pointed out, was very restricted because HF squadrons could not be put on the same frequency as VHF squadrons. There was only a fifty-fifty chance that when two squadrons were ordered off in company that they would be able to communicate with each other. Park therefore asked for the highest priority in fitting VHF equipment in the third squadron at stations in his group. Once this much superior equipment was generally installed, the employment of large formations by Park’s successor became a feasible tactic.

On 21 October Air Vice-Marshal L.D.D. McKean, head of the British air liaison mission in Ottawa, informed Park that Billy Bishop, one of the most famous pilots of the First World War, had been greatly taken with Park during his visit to England early in October. McKean enclosed press cuttings in which Bishop, now an Air Marshal in the Royal Canadian Air Force, said of Park: ‘He impressed me more than any man I have ever met.’ Park thanked McKean for the ‘amusing’ cuttings reporting Billy’s ‘excellent propaganda’ and sent both Bishop and McKean copies of his report on air fighting in September and October. McKean thanked Park on 22 January 1941. It was the first time, he said, despite numerous applications to the Air Ministry, that he had received anything of real value concerning operations:

I was immensely struck by the way you were always thinking ahead of the Hun, and I would add that from what I have heard from other sources there can be no question of the tremendous reputation your Group has gained in first-class efficiency.

Unfortunately, Park was less adept at thinking ahead of the Air Ministry and by the time he read McKean’s praise had long been dismissed from his command.

Despite his losses and strains in the great daylight battles, Park was eager to mount an offensive at the first opportunity. He told his sector commanders on 21 October that the Germans could not assemble and launch mass raids from north-west France later than ninety minutes before sunset if they hoped to return to base in daylight. He therefore proposed to use that period to surprise them by making strong sweeps over their airfields. Dowding had ruled against such sweeps, as Evill politely reminded Park on 2 November, but Douglas – who replaced Dowding on 25 November – was anxious to ‘lean forward into France’ and now ordered Park to look into the possibility of escorting bomber raids as well as making fighter sweeps. On 20 December, a few days after Leigh-Mallory replaced Park at 11 Group, two Spitfires attacked a German airfield at Le Touquet. This attack marked the start of the counter-offensive, one that Park had very much in mind weeks before his dismissal.11

He also had night operations very much in mind from September onwards. His Blenheims proved quite unsuitable and at the end of October the Air Ministry decided to form two night-fighter wings, of two squadrons each, at Gravesend in Kent and Rochford in Essex. Park looked forward to the introduction of the Beaufighter, specially developed for night-fighting, and the opportunity to carry out intensive training. But his sector operations rooms, working almost continuously, were not free for long to practise controlling night-fighters and exercises in remote areas were of little use. Many more Beaufighters fitted with AI Mark IV radar equipment were needed, he wrote, but both aircraft and equipment suffered so many technical failures that only the most devoted nursing by day enabled them to function at all by night.

On 12 November Park issued instructions for the operation of the two night-fighter wings. Tactics, he said, were ‘those of a cat stalking a mouse rather than a greyhound chasing a hare’. He went on to discuss the type and number of aircraft to use for differing conditions, their control and operation, area of patrol and cooperation with ground defences – guns, searchlights and balloons. He would have made a good night-fighting organizer. He certainly covered the subject shrewdly and in detail in his report of 7 November and in these instructions. Douglas, so quick to comment on the absence of such coverage at a time when there had been little night activity, refrained from comment now. If Dowding and Park had to leave their respective posts in November and December 1940, would it not have made sense for one or both to be assigned to the night defence problem? It would have been beneficial to divide the problems of day and night defence: they required different aircraft, aircrews, tactics and methods of control.12

Park wrote to Squadron Leader Max Aitken (son of Lord Beaverbrook, then Churchill’s Minister of Aircraft Production) on 7 November, sending him a copy of his account of operations in September and October. He drew Aitken’s attention specially to his paragraphs on aircraft performance. Aitken replied on the 10th, having shown those paragraphs to his father: ‘Actually, I have been talking "height" to him for some weeks,’ he wrote. Park was delighted to hear that Beaverbrook was interested in the problem of providing high-altitude fighters for the spring offensive. ‘I hope by then,’ he replied, ‘to have a few additional squadrons and to make it really offensive, instead of struggling against superior numbers over home territory.’ Park wrote again to Aitken on the 14th. Dowding had telephoned, he said, and was angry that Beaverbrook had seen the report before it was officially submitted. Park had answered that he had sent it to Aitken because he had a lively interest in the subject, but ‘that did not placate him, and you may expect to see me selling newspapers on the corner of Piccadilly and Haymarket any day now. If so, you will at least know that I got fired in a good cause.’ Within days of penning this pleasantry he had in fact been fired; so, too, had Dowding.

In mid-November, Park sent a report to Wing Commander Sir Louis Greig, Sinclair’s secretary, on the unsatisfactory situation in regard to works services and transport facilities at the majority of his fighter stations. These were all matters that had been raised for months past, he wrote. Though always very sympathetic, he continued,

Higher Authority has proved quite incapable of meeting the most urgent requirements of the fighting units, which leads one to suppose that the existing machine is beyond the stage of requiring a little lubrication, but requires a sledge hammer.

The Duke of Kent, recently appointed Welfare Officer in Park’s group, ‘is quite incensed at the general discomfort and lack of facilities he has had pointed out at every station he has visited.’

A fortnight later, on 27 November, Park wrote to Greig again, thanking him for his help in improving living conditions at fighter stations. He had landed at Biggin Hill a few days earlier, ‘and to my surprise found there the Director of Works, accompanied by many experts, busily taking down notes and conferring with the Station Commander.’ The Duke, however, ‘appears to have lost interest now that he has heard that I am leaving the Group,’ but Park would try to revive his enthusiasm.

He sent copies of his September-October report to several senior officers, emphasizing that it was fuller and more interesting than his earlier reports. Leslie Gossage, his predecessor at 11 Group and now Air Member for Personnel, thanked Park for a copy on 26 November. ‘You leave behind you a record of fine achievement,’ he wrote, ‘and have given the country an overwhelming sense of security during the hours of daylight and, maybe, by night too, before long!’ Park replied next day:

As the senior members of my Group Staff deserve the lion’s share of the credit for our successes, I am taking the liberty of showing them your letter, because they have not had much recognition apart from my own thanks at the end of each phase of the operations.

He was glad that the pilots had received immediate and liberal recognition, but there were many officers and men spread around his twenty-six fighter stations whose gallantry, good judgment or hard work had so far been ignored.

Gossage thought the lack of recognition was a result of the command’s preoccupation with the battle, but Park disagreed. During the past seven months, he told his senior staff officers on 10 December, recommendations for non-immediate and periodic awards had been called for. With few exceptions, those from station and squadron commanders had been forwarded by Park to command headquarters with his strong recommendation. ‘After considerable delay’ and ‘after having been pruned’, they were forwarded to the Air Ministry. Park knew that Dowding took a hard line on honours and awards even for acts of gallantry and rarely considered them justified for continuous hard work: public recognition meant little to him and he disdained its appeal to others. In such matters, among others, Park was a more imaginative and sensitive commander.13

Park served out his last days in the command under Douglas’s orders. He attended a group commanders’ conference at Bentley Priory on 29 November. Douglas announced that he was keen to get away from a purely defensive outlook and, when weather permitted, wanted sweeps carried out over Calais by one or even two wings (of three squadrons each) to ‘practise squadrons in working in large formations.’ Park said that his squadrons had been operating occasionally in this way and showed great enthusiasm for the work. He was asked by Douglas to get in touch with Bomber Command to see if these fighter sweeps could be combined with any of their operations.

On 3 December he sent Douglas a report on air fighting in November. G.M. Lawson, Group Captain (Ops.), minuted Evill on the 11th about ‘another excellent report’ from Park. His group had ‘dealt with the changing tactical situation in an able manner.’ The air-sea rescue system, as Park pointed out, was unsatisfactory. Coordination between 10 and 11 Groups was admirable, but it remained to be seen whether 12 Group’s wing could be operated efficiently in future. Park had again omitted to include the number of pilots wounded and injured with the figure of those missing and killed. Hence his picture of air combat was too favourable, as in his earlier reports. Like Lawson, Evill drew Douglas’s attention to the weakness of the air-sea rescue system, which must be improved if the command were planning more offensive action. Evill did not think Park’s reaction to the resumption of attacks on convoys was as spontaneous as he implied, but his measures were certainly successful and his controllers almost always reacted quickly enough when estuary shipping was threatened. Although the control of reinforcing squadrons was being made easier by the introduction of VHF, a real solution was mainly a matter of inter-group cooperation. Evill agreed with Park that little had been done to examine training methods in the groups with a view to selecting the best ideas and bringing them into general use. He also agreed that training was essential to the success of night interception. While these comments on his last report were before Douglas, in mid-December, Park was packing his bags for exile in deepest Gloucestershire.

The Battle of Britain was, in fact, a campaign lasting 114 days, from 10 July to 31 October. Over such a long period, there were many changes of strength in the respective forces, caused by efforts to increase rates of production and repair as well as by destruction and damage. There were also marked differences between the numbers of aircraft available on station, combat-ready or unserviceable at any one time. This is why no two books on the subject use the same figures. In round figures, however, the Luftwaffe usually had about 2,250 aircraft combat-ready: 1,250 bombers (including 250 dive-bombers) and 1,000 fighters (including 220 twin-engined fighters). Opposing this force, Fighter Command in July had 750 effective fighters (450 Hurricanes and 300 Spitfires), of which 600 were combat-ready. These forces increased by nearly ten per cent in August and September. Over the whole campaign, Fighter Command lost 537 aircrew killed and as many again badly injured out of some 3,000 aircrew who made at least one sortie. The Luftwaffe lost almost five times as many men killed (2,662) and more than 6,000 wounded or captured. The British lost ten fighters for every nineteen German machines destroyed: 1,023 for 1,887 in total.