6

Some Practical Consequences

IN THIS CHAPTER I TURN to the implications of relational morality for some first-order questions about what it is right and wrong to do. According to the relational approach, actions are obligatory or morally right just in case there are individuals who have claims against the agent to their performance. But there are a variety of particular duties that seem difficult to wedge into this framework. These include, for instance, cases in which directed obligations do not seem to correspond to any assignable Hohfeld-style rights, such as duties of gratitude and of mutual aid. Another class of potential problem cases are those in which morality apparently requires us to take into account the aggregate effects of our agency on the many people who might be affected by it, rather than considering its bearing on the personal interests of individuals, one by one.

The field of first-order normative ethics is exceedingly capacious, and I can obviously only scratch the surface of it in the space of a single chapter. Even the central example to which I have repeatedly returned in this book, that of promissory obligation, raises issues that I have hardly begun to address, and that will also not be resolved in the present chapter (concerning, for instance, the precise nature of the personal interests that ground promisees’ claims to promissory fidelity). My larger aim in this book is to make a case for the fruitfulness of understanding moral requirements in relational terms. To this end, it is not necessary to resolve specific questions about what exactly we owe it to other people to do, morally speaking; nor do we need to clarify the justifications that figure within moral reflection in all cases. The hope, rather, is that readers can be persuaded to agree that first-order moral questions are aptly characterized in relational terms, as questions about the claims that individuals hold against each other, just insofar as they are each members of the manifold of moral persons. For this purpose, however, it will be necessary to say something, at least in general terms, about the kinds of moral issues that have seemed especially resistant to treatment within a relational framework.

I begin by discussing some of the cases in which it seems most intuitive to think of moral duties in directed terms, as owed to other persons. These cases turn out to be surprisingly disparate in character, raising the question of whether they have any important features in common that might preclude the extension of the model of directed obligation to the entirety of the moral domain. One feature I focus on is the foreseeability of a specific individual as the person to whom duties of these disparate kinds might be directed. This leads me to consider some cases in which it has been alleged that others can be wronged by our actions, even though the individuals who are wronged are not discernible as claimholders by us in advance of acting. I suggest that cases of this kind, to the extent they are agreed to be plausible as cases of moral wrongs, can be understood to involve secondary claims, which are parasitic on the first-order claims held by discernible individuals.

Secondary moral claims such as these, if there really are such, would diverge in certain ways from familiar Hohfeldian claim rights. Other cases in which the moral claims posited by relational morality differ from assignable moral rights include cases of imperfect moral duty, such as duties of gratitude and mutual aid. I discuss these examples in section 6.2, suggesting that we can make sense of them within a broadly relational framework if we adapt the notion of a moral claim in ways that seem to me independently defensible (if also, perhaps, somewhat surprising).

In the final two sections of the chapter, I discuss some cases that are widely taken to be especially challenging for relational conceptions. These are cases that involve the non-identity problem, where the assignment of claims to individuals has the paradoxical consequence that the individuals would not have existed had the claims been honored, and cases, such as those involving rescue situations, in which the number of people who might be affected by our actions seems to matter to moral thought. Cases of both kinds have generated a very large literature, and I have no expectation of being able to do justice to them here. My very limited aim will be, instead, to point out that the most important of the non-identity cases can in fact be accommodated in relational terms, and to sketch an overlooked way in which the numbers might count within a conception of moral deliberation that is focused on the claims of individuals.

I concede, however, that there may be some cases involving aggregation that cannot be accommodated neatly within a relational framework. In section 6.4, I propose that we understand cases of this kind to elicit normative intuitions about the extramoral significance of human life and well-being. Considerations of this kind may have an important role to play in certain deliberative contexts, where legitimate authorities have decisions to make about the allocation of resources under conditions of scarcity, but this is compatible with their lacking the same kind of significance in contexts of individual deliberation. I conclude by suggesting that if well-being has independent significance for individual deliberation, it is not as a consideration that outweighs the duties of relational morality, but as a potential source of independent requirements that might conceivably conflict with what we are morally obligated to do.

6.1. Foreseeability, Claims, and Wrongs

In section 4.1 above, I noted that directed obligations are often understood by philosophers to arise out of historical relationships between the parties that they link. Joseph Raz, for instance, has suggested that there are three kinds of personal relationship that can generate a directed duty between two people: commitments or undertakings by one party toward another; thick social ties, such as those that connect friends and family members; and the relationships that underlie debts of gratitude.1 About directed obligations of these kinds, he also observes that some of them do not correspond to anything we would intuitively think of as a right on the part of the person to whom they are directed; and that we cannot, in any case, understand all of morality to consist of such obligations. This first of these two further claims seems to me correct, though I reject the second of them.

Before getting to these issues, however, it will be well to look more closely at some of the cases in which Raz takes personal relationships to give rise to directed obligations. For they are surprisingly disparate in character. One subclass of cases involves interactions that can be understood to give rise to literal or metaphorical debts of some kind. There is, for instance, the kind of undertaking whereby people accept a benefit from another party in exchange for a commitment to provide a benefit to that party at a later time. Think of a commercial transaction, such as the consumer contract that gives you a television set now on the condition that you make monthly installment payments to the store over the next three years. In this kind of case, one has incurred through the transaction a financial debt that one owes it to the other party to repay, in accordance with the contractual terms. With debts of gratitude, we have something similar, only the debt to be repaid is generally figurative rather than literal, and the terms of repayment leave more to the discretion of the indebted party (a point to which I return in the following section). In these kinds of cases, the personal relationship that gives rise to the directed obligation is one that confers a benefit or advantage on the agent who stands under it, and the feeling that the agent owes something to the other party goes together with an awareness of a kind of imbalance between them that needs to be righted.

Some of the debts that give rise to directed duties are incurred voluntarily, including the transactional ones that involve commercial and other forms of contracts or commitments. But others are not, including many debts of gratitude, which result from kindnesses or advantages bestowed on a person who has not necessarily done anything to bring them about. This is clear, too, in at least some cases involving social ties, such as those that link the members of biological families. Children obviously do not get to choose their parents, and yet they are generally understood to have obligations of various kinds that are owed to them. These directed obligations might be understood, at least in part, as a special case of debts of gratitude, insofar as children have generally benefited extensively from the exertions that their parents undertook to raise them.2 Here, as in other such cases, the sense of obligation to the parents might be traced to the positive effects that one has enjoyed as a result of the historical relationship, which somehow need to be repaid, even if they were not voluntarily incurred.

But this feature, too, is not essential to Raz’s examples of familiar directed duties. In other cases that involve close social ties, it is implausible to suppose that the sense of a duty owed to the other party has much if anything to do with an awareness of oneself as having enjoyed a benefit that needs to be repaid. Friendship, for instance, typically does not have this character. To be sure, it represents a great good for the parties to it; but the good is one that is symmetrically enjoyed by both of them, rather than involving an imbalance of burdens and benefits that somehow requires to be righted, going forward. And yet friends are naturally understood as having special obligations that are owed to each other. A similar point might be made about the relationship in which parents stand to their children. Naturally this is a tremendously valuable form of human relationship, representing one of the great goods of which humans are capable; and people who have relationships of this kind clearly owe various duties of care and concern to their children. But it would be odd to theorize these directed duties as involving the enjoyment of benefits that now stands to be paid back to the party who has bestowed it.3 The debt model, in either its voluntary or its nonvoluntary variants, simply doesn’t apply to cases such as these. Nor is it a felicitous template for understanding promissory obligation, which is another Raz-style undertaking that is conventionally understood to give rise to a directed duty. Promisors bind themselves to promisees by giving them their word, but these commitments are in force regardless of whether there is an asymmetry of benefits and burdens between the parties that requires to be rebalanced.4

Raz’s examples are all cases in which directed duties are generated by historical relationships between the parties to them. But as we have just seen, it is difficult to discern any significant feature that they might be understood to have in common, beyond their being cases in which directed duties are relationship based. The most we could say, perhaps, is the following. First, the diverse historical relationships at issue in these cases all serve the function of rendering discernible the particular claimholder to whom the directed duty is owed. For instance, out of all the countless friendships that exist in the world, the duties that I owe as a friend are directed to the specific person with whom I have interacted in a relationship of this general kind. The relationship thus helps to individuate the claimholder, making foreseeable to agents the persons to whom they are linked in a specific relational nexus.

Second, in each of the cases considered so far, it seems there is a valuable relationship of some kind that is in play. In many cases, the valuable relationships in question are the very ones that play the individuating role. This is the pattern we see in the examples involving friendship and family relationships, where ties of love that are immensely important in human life also serve to pick out the specific individuals to whom directed obligations are owed. But the pattern does not extend to all of the Raz-style examples. The consumer contract that is entered into when the purchaser of a good commits to making future payments to the seller helps to individuate them, as parties who are connected to each other by a specific directed duty and claim. But the contractual relationship is not itself necessarily valuable; on the contrary, as noted above, it is tempting to think of it as involving a worrisome imbalance between the linked parties that requires being restored to equilibrium. The valuable relationship in this case, and in many other cases of promissory commitment, is one that is enabled through compliance by the agent with the terms of the directed obligation. This behavior serves to right the imbalance between the parties that is created by the original commitment, or to enable promisors to realize in their relations to promisees the value of interpersonal recognition discussed in section 4.4 above.

Once we are clear about these points, however, then it looks as if the role of personal relationships as a basis for directed duties is dispensable. There has to be something, perhaps, that renders claimholders discernible by the agents against whom their claims are held. It is also plausible to suppose that compliance with the relational duty that is owed to those individuals should realize a valuable way of relating to them. But these conditions can be satisfied even in cases in which there is no antecedent relationship at all between the parties. This brings us back to a theme from chapter 4, where I argued that morality might be understood to consist in a set of self-standing relational requirements. Thus, consider the case of a face-to-face encounter with an individual whom you have never met before, but who stands to be affected significantly by something it is open to you to do. (To return to a recurring example, perhaps she is lying on the sidewalk with an obvious case of gout, and your continuing trajectory would cause a painful encounter with her outstretched foot.) Here it is clear enough from the situation which individual might be understood to have a claim against you not to cause her easily avoidable distress. It also seems that acknowledgment of this claim against you would enable you to relate to the individual in a valuable way, on a basis of what I have called interpersonal recognition. So it appears that there is no obstacle in the way of extending the relational model of moral obligations and claims to a situation of this kind, despite the absence of any antecedent relationship between you and the individual to whom the duty is directed. You owe it to the stranger on the sidewalk to avoid a painful encounter with her diseased appendage, and this thought is fully available to you in the situation I have described.

There are, of course, plenty of cases in which our actions have significant effects on individuals who are not foreseeable in advance of our performing them. Cases of this description figure prominently in a novel interpretation that Nicolas Cornell has recently advanced of the notion of a moral wrong.5 Cornell holds that there are two ways in which people could be wronged morally by the actions of another party. They might, first, have rights that are infringed through the party’s actions. Or they might, second, be affected adversely by actions of the party that infringe somebody else’s rights. In cases of the latter kind, there will be a moral wrong that does not itself violate the claims of the persons who are wronged, and that therefore cannot be understood to involve attitudes of disregard for those persons’ claims or for the interests that underlie them. Cases of this kind would thus fail to fit the schema I have offered in this book for understanding the idea of a wrong or a moral injury, which connects these notions closely to that of a claim.

Cornell’s argument for his conclusion is driven by consideration of a range of more and less familiar cases, which he believes elicit the firm intuition that people are often wronged by actions that do not infringe rights of theirs in particular. There is, for instance, the case of the third-party beneficiary to a promissory transaction (where, in at least one common variant, A promises B that A would look after B’s mother, C). Cornell agrees with H. L. A. Hart and others that it is B rather than C who holds a moral claim against A to promissory fidelity in a case of this kind;6 but he thinks that C would be wronged by A’s action if A were to fail to honor the promise that was owed to B (thereby violating B’s right). Another example with this alleged structure is the well-known case of Palsgraf v. Long Island Railroad Co. Here the employees of the railroad negligently rush a passenger onto the carriage of a moving train, dislodging the passenger’s luggage in the process, which happens to have contained some fireworks; as a result of the mishap, the fireworks explode, causing a scale to topple over and injure Mrs. Palsgraf, who was standing in a different area of the platform. The New York Court of Appeals ruled that the railroad company was not liable for the harm to Palsgraf, who had no right against them to protection from harms that were not foreseeable. But Cornell thinks Palsgraf was nevertheless clearly wronged by the actions of the company’s employees, insofar as these caused her significant harm. And similar conclusions may be reached about a range of other cases in which adverse consequences accrue to individuals as a result of actions that violate the claims of another party, including harms caused by overheard lies or negative effects that fall to family members of individuals whose rights have been infringed (such as the parents of a child killed in a car accident involving a drunk driver).

I do not myself share Cornell’s intuitions about many of his cases. In most of them, the details that would make it plausible that a third party is wronged through the agent’s action would also provide a basis for an antecedent claim or right that is assignable to that individual. If A’s promise to B induces C to rely on A to provide the assistance that C needs, and this effect could be anticipated by A at the time the promise was made, then it seems to me pretty clear that C has a claim against A to such assistance, even if C was not the addressee of A’s promise. Similarly, if people make misleading statements about matters of general interest in a public setting, they may negligently violate a duty of due care to ensure that others in causal range of them do not form false beliefs based on their behavior and speech. In virtue of occupying the same public space with the speaker, those whose beliefs are apt to be influenced by the speaker’s utterances are foreseeable as potential claimholders, even if they are not the immediate object of the speaker’s attention at the time when the deceptive statements were put forward.7

Furthermore, it seems to me that we all have claims against other people that they should not act to harm those we love, or subject them to significant and avoidable risk of harm. We may not be known specifically by the wrongdoers in cases of this kind. But insofar as the immediate victims of their actions can be discerned by wrongdoers, they have cognitive access as well to these additional claimholders. It is well known, after all, that each individual is connected to other persons through chains of love and affection, and that their personal interests will also be damaged if the individual to whom they are attached is harmed by the malicious or reckless conduct of the wrongdoer. These effects on friends and family give them a reasonable basis for complaint about the things that are done to those to whom they are attached. In Palsgraf, on the other hand, it may be more difficult to assign a clear claim to the person who suffered an injury as a result of the wrongful conduct. Here, the individual who was harmed by the railroad employees’ conduct was really not foreseeable in advance by them, in part because they had no reason to believe that the luggage contained explosives that might pose a danger to passengers waiting innocently on other parts of the platform. But then, the court that decided the case seemed to agree that there was no clear wrong to the injured party under the civil law of tort.8

Having made these observations, I do not wish to insist that Cornell is incorrect in his verdicts about at least some of the cases he discusses. There is a rigorist tradition, to which he alludes, of thinking that people can rightly be held to account for the harmful consequences that flow from the wrongful actions that they perform.9 If holding morally accountable is an ex post response to actions that wrong another party, as I suggested it is in chapter 3, then this might entail that the parties who are harmed in such cases are also morally wronged. Note, however, that by Cornell’s own reckoning, the wrongful actions that harm third parties count as wrongs to those parties only if they violate somebody’s rights or claims.10 This strikes me as a significant concession, pointing toward a different account from the one he favors of what might be going on in cases with the structure he describes.

People who flout their relational moral duties disregard, in the first instance, the claims that are held against them by the people to whom the duties are owed. In doing this, however, they can also be said to have shown neglect for the social dimension of their agency, including its bearing on the personal interests of those who stand to be affected by it. But we all have a stake in people taking seriously this dimension of their conduct. One way to articulate this thought within a relational conception of morality would be to assume that we each have secondary claims not to be harmed as a result of conduct that flouts, in a primary sense, the moral claims of other parties. These secondary claims will be apt to proliferate rampantly in any given case, and in a way that is not foreseeable by agents, insofar as there are any number of unpredictable harmful consequences that could potentially befall third parties as a result of wrongful exercises of their agency. But the proliferation of claim-holders is not a problem, in itself (as we shall see in more detail in section 6.2). As for foreseeability, that too does not seem to be an obstacle to the assignment of secondary claims in these cases, insofar as that assignment is parasitic on the assignment of primary claims to parties who are foreseeable by the agent. Agents might owe it to individuals in the larger community to protect them from the harmful consequences that could result when they flout the primary moral claims that others hold against them. The way to live up to these secondary responsibilities would be to honor the primary claims of other parties, and this is something that it is anyway reasonable to expect them to do.

Though I do not wish to take a stand on the plausibility of this general picture here, it seems to me a promising way to accommodate the intuitions Cornell is trying to marshal within a thoroughly relational conception of moral wrongs. There are clearly personal interests that each of us has in not being harmed or affected adversely as a result of the agency of other persons. And these interests might well ground secondary claims that we have against agents, which piggyback on the primary moral claims of other parties, and which find expression in complaints we have against agents in cases in which we are harmed through their neglect of the primary duties that they owe to others. To put this reasoning in contractualist terms, people who stand to be harmed by actions that wrong another party have an objection, based in a personal interest of theirs, to principles that permit such actions. What counterobjections might agents bring on their behalf to principles that prohibit such actions? They are, by hypothesis, already morally impermissible, which means that the agent’s objection to a prohibition on them is weaker than the objections of those in the position of the primary claimholder. It follows that it isn’t intolerably burdensome on people in the agent’s position to expect that they should refrain from the actions that are in question. But then, it would also not seem unreasonable for people who are adversely affected by such actions to object, on their own behalf, to the agent’s performing them.

In neglecting or disregarding the primary claims that others have against them, agents could be said to be thereby disregarding the secondary interests that unforeseeable third parties have in not being subjected to avoidable harms. As agents, we cannot completely immunize people against the harmful effects that might befall them through our actions. But it is in our power to see to it that we honor their primary claims against us; and it is a coherent further thought that we might also owe it to members of the larger community of moral persons to protect them from the adverse consequences that sometimes result when we flout these foreseeable primary responsibilities.11

Secondary claims of the kind just described, if there are such, would not be a hugely important part of the moral landscape. But my present point is that they are at least intelligible within the kind of relational framework I have been developing. If it is accepted that these secondary claims exist, however, they would be unlike familiar Hohfeld-style rights, in at least some respects.

It is sometimes said that rights of this kind need to be “enforceable,” and that enforceability in turn presupposes that there are agents to whom the corresponding directed duty can clearly be assigned.12 I am not entirely sure what exactly “enforceability” is supposed to come to in this connection, or whether it legitimately applies to all cases of moral rights (in contrast to what we might call juridical or political rights).13 It does not seem to me to be a general condition on the intelligibility of moral rights that it be permissible for the bearer of them to use physical coercion to ensure that they are honored. Promisees, for instance, cannot in this way force promisors to uphold their promissory commitments. But perhaps the internalization of claims as a basis for accountability relations, including subjection to reactive and other forms of blame, could be understood as a form of enforceability appropriate to moral rights. It might then be maintained that moral rights should at least be enforceable in this manner. But I have argued that this kind of enforceability condition is satisfied by any moral consideration that rises to the status of a claim, including the secondary claims characterized above. This shows itself in the fact that it would be fitting for the bearers of the claims, if there are such, to resent the agents who flout them by engaging in wrongful conduct that ends up harming them.

But there are other features of Hohfeld-style rights that seem to be missing in these cases. One of these is that the class of secondary claimholders can be identified only ex post, after the wrongful action has been performed. What they allegedly have is a claim not to be harmed through wrongful agency, rather than a claim not to be exposed to the risk of harm; but we cannot tell whether wrongful conduct will in fact harm a third party in unforeseeable ways until it has taken place. This makes it virtually impossible to identify in advance specific agents to whom the corresponding obligations not to harm might be attached.14 This connects to the fact that the claims in question are not able to function, in the deliberation of agents, as considerations with independent normative significance; their relevance to deliberation, as noted earlier, is inherited from that of the primary rights on which they are parasitic. There are potential moral considerations here with an implicitly relational structure, but they differ in this way from paradigm cases of moral rights.

Another feature that we associate with the familiar examples of rights is ex ante determinacy in regard to the behavior to which the right-holder is entitled. Our basic defensive liberty rights, for instance, include fairly determinate claims against others, specifiable in advance, not to initiate intentional bodily contact without our consent (barring special circumstances), not to impede our free movement through public spaces, and so on. And promisees’ moral rights against promisors include the claim against them (again, barring special circumstances) to see to it that the specific terms of the promise are upheld. Where ex ante determinacy of this kind, as to the specific behavior that is expected of an agent, is not in place, I think we would be reluctant to understand the situation as involving an assignable moral right. This may be a further respect in which secondary moral claims do not resemble standard cases of assignable moral rights, insofar as there is no way to specify determinate standards of ex ante conduct to which they allegedly connect. Finally, rights are generally understood to be considerations that connect to behavior that specifically affects the bearer of the alleged right. Thus, suppose an agent is under a duty to do something that won’t (as it happens) affect me at all, and that isn’t intended to affect me. I might conceivably take an interest, of a suitably non-personal kind, in whether the duty is fulfilled. But it would strike us as odd to say that I have a right against the agent so to act. Rights are intuitively assignable to individuals, it seems, only in cases in which the determinate actions to which those individuals are entitled are ones that would promote their personal interests in some way.

According to a relational conception, however, it seems there will be some primary moral claims that do not have these salient characteristics that we associate with moral rights. I turn to some important examples of this kind in the following section.

6.2. Claims without Rights: Imperfect Moral Duties

In the section 5.3 above, I noted one important difference between moral claims, as I would propose that they be understood, and Hohfeldian moral rights. Moral claim rights are often taken to be considerations that we reflect on within moral deliberations, and that we might permissibly infringe. By contrast, the relational interpretation takes moral deliberation to culminate in the assignment to individuals of moral claims. In this section I want to consider some specific moral claims that we would ordinarily be reluctant to classify as rights. These are claims that correlate with so-called imperfect moral duties. Ultimately it seems to me fairly unimportant whether we designate these claims as rights, or call them something else instead. But the features of them that lead us to reject the talk of rights in this context might also suggest that the moral considerations in question cannot be accommodated within the kind of relational view I have been developing in this book. So it is important to take a closer look at their nature and structure.

Suppose that another person does you a kindness, at significant personal cost—say, stopping at the side of a dark and lonely road to help you fix a flat tire, with the result that she gets home very late, very hungry, and needing a shower. The act of benefiting you is normally understood to involve a change in your moral relations, bringing it about that you now stand under a moral duty of gratitude. This way of speaking is perfectly natural, but it lacks at least some of the elements that we tend to associate with directed obligation. In particular, we would normally balk at assigning to the benefactor a moral right to your gratitude for the kindness that was bestowed on you.

Another case of this general kind involves duties of mutual aid. We all have moral obligations to assist those who are in serious distress, even at some significant sacrifice. But there are of course many different potential beneficiaries in the world, and it is not remotely the case that we can personally do anything to assist more than a small number of them. We intuitively have significant discretion, as it were, to determine for ourselves how we will live up to the requirements of mutual aid. Under these moral conditions, we would ordinarily not want to say that any of the potential beneficiaries of our efforts has a specific moral right against us to our help, despite the fact that we have an obligation (perhaps a very weighty one) to contribute to relieving the acute needs of people in their position.

The general question that is raised by such cases is whether they can be made sense of within the framework of the relational interpretation of morality that I have been developing in this book. There are moral obligations here, but apparently nothing in the way of assignable moral rights. Can we nevertheless understand the obligations to be directed to specific claimholders, in accordance with the schema of relational morality that I have been presenting?

Let’s start with gratitude. It is natural to think that debts of gratitude are owed by beneficiaries to those who have bestowed benefits on them. Indeed, as noted in section 6.1, Raz cites cases of this kind as among the salient examples of personal relationships that can give rise to directed duties. But Raz also agrees with my observation that benefactors would not ordinarily be understood to have a moral right to the gratitude that beneficiaries are under a duty to display. What might lie behind the reluctance to assign rights to benefactors, especially given the fact that the obligation seems to be one that is owed to them in some way? One consideration might be alienability. Many moral rights can be waived by the person who is their bearer, through the right-holder’s consent to the actions that would ordinarily count as infringements. I can waive my right against you that you not trespass on my property or body by inviting you into my home, or by consenting to the surgical procedure whereby you would remove the mole on my chin. But the benefactor cannot in the same way waive the obligation on the part of the beneficiary to reciprocate with gratitude for the kindness that was done. This consideration is inconclusive, however, since it is controversial (to say the least) to suppose that alienability is built into the idea of a moral right. There is certainly no incoherence in supposing that some basic rights, such as the right not to be enslaved by another person, cannot be alienated by any voluntary exertion of the right-holder’s will.15

In most cases of this kind, the reason why the right will be inalienable is that it is grounded in personal interests on the part of the right-holder that are especially important, perhaps on account of their connection to the right-holder’s moral standing. But nothing like this seems to be the case with duties of gratitude. So that is one feature of gratitude that we need to make sense of. Another is the discretion that beneficiaries seem to have to determine for themselves how they are to fulfill the duties they undertake by accepting another person’s generously bestowed benefits. This latter feature seems especially important to the question of the assignment of rights to the benefactor. As we saw in the preceding section, rights seem to be most clearly in place in situations where there is a specific category of performance that the right-holder has a claim against other people to engage in. Thus rights to property or bodily integrity involve claims against other people that they not engage in unauthorized trespass, and promissory rights involve claims against promisors to keep their word. But there is nothing so specific in play in the gratitude case; it isn’t as if the benefactor can insist, say, that the person benefited should take her out to dinner at a nice restaurant on a day of her choosing, even if a performance of that kind would count as satisfying the beneficiary’s duty of gratitude.16

It would take us too far afield to attempt a complete explanation of the importance of agential discretion in the case of gratitude. But a plausible account might begin by emphasizing the function of these duties in restoring an element of equality into the relationship between the benefactor and the beneficiary.17 As I noted in the preceding section, directed duties that involve literal and figurative debts to another individual are cases in which there is often an imbalance between the parties that is restored to equilibrium through the discharging of the duty. This is obvious in cases involving literal financial debts, but it also seems present in cases of merely metaphorical debts.

In the gratitude case, the figurative debt is a matter, in part, of the receipt by the beneficiary of some concrete advantage that has been bestowed by the benefactor. If this were all that the imbalance involves, however, then the debt of gratitude that restores equilibrium should be comparatively straightforward to calculate, and the role of discretion on the part of the benefactor would remain mysterious. But there is a distinct element to the imbalance created by the benefactor’s act that hasn’t yet been acknowledged, involving the beneficiary’s dependency on the agency of the benefactor.18 In our original example involving the flat tire, the benefactor’s act of generosity, though it confers a clear benefit on you, also takes something away from you, namely, your active role in shaping the relationship with the benefactor on common terms. What is needed, then, is not merely a repayment of the positive benefit, but a mechanism of repayment that also corrects the disequilibrium of dependency and agency that has emerged between the parties. By undertaking to reciprocate for the favor that was bestowed, beneficiaries assert agential control as partners to the relationships in which they stand to their benefactors, something that is not really possible so long as gratitude is not displayed or performed. But if gratitude is a mechanism for effecting the transition from dependency to agency, it makes sense that beneficiaries should have wide latitude to determine for themselves the specific form that their gratitude will assume. It also makes sense that benefactors should lack discretion to waive the duty of gratitude that is in place, since their doing so would only serve to exacerbate the dependency that the duty of gratitude is meant to help overcome.

Even if we do not speak of a right to gratitude in these cases, however, it nevertheless seems to me that there is a residual claim that is in place, one that corresponds to the familiar idea that the duty is owed by beneficiaries to their benefactors. The claim is not to any specific action on the part of the beneficiaries of the kind that, on its own, would be understood to discharge their debts. It is, rather, a claim that the beneficiaries should exercise their discretion to do something to restore the agential imbalance that has emerged, by reciprocating in some way for the kindness that was originally done to them. A moral consideration of this kind, insofar as it makes essential reference to the discretion of the beneficiary, lacks the determinacy characteristic of cases involving standard moral rights. But it includes the other elements that are familiar to us from the relational framework. It corresponds to a duty that is understood to be directed to the benefactor, and to the extent that this is the case, we can understand it as a claim held by the benefactor against the beneficiary. This shows itself, further, in the fact that a failure to discharge the debt of gratitude that is held by the beneficiary would not merely be wrong, but something that wrongs the benefactor in particular. It would reflect the kind of disregard for claims that gives rise to a grievance or moral injury, understood as a privileged basis for reactive and other forms of blame.

I would note, however, that the benefactor might not be the only moral claimholder in cases of this general kind. Benefactors have specific interests in conducting relationships with others on a basis of agential equality; to put things in contractualist terms, this gives them a reasonable ground for objecting to principles for the regulation of behavior that permit beneficiaries to refrain from reciprocating for benefits received. But beneficiaries, too, have a strong personal interest in conducting relationships on this basis, one that might ground a reasonable objection on their own behalf to the same principles. This suggests that beneficiaries might owe the debt of gratitude not only to their benefactors, but also to themselves, and that they have a claim against themselves to live up to the debt, one that runs in parallel to the claims that are held by their benefactors. Among other things, this would help to make sense of the feeling that gratitude can intelligibly lead beneficiaries to bestow benefits on people other than their immediate benefactors (for instance, in cases in which there is no longer anything that can be done to reciprocate for the favor that was done to them).19 A consequence of this way of thinking would be that beneficiaries who fail to discharge their debts of gratitude would not merely have wronged their benefactors, but also themselves, giving them a retrospective grievance about their own past conduct. We might express this aspect of the situation by saying that they failed to take advantage of an opportunity that was open to them, at the earlier time, to restore agential equality to a personal relationship to which they were a party. As with the secondary claims considered in section 6.1 above, this may not be the most important dimension of cases involving debts of gratitude. But it is something that is intelligible within the relational framework, and that helps us to make sense of features of these cases that might otherwise seem puzzling.

Turn next to the case of mutual aid. Here, too, though there are duties that we stand under to help people who are in severe distress, we are reluctant to suppose that any specific individual has a claim against us to such assistance. And here too, our reluctance to ascribe rights to potential beneficiaries seems to go along with the discretion that agents are understood to have to determine for themselves how the duty is carried out. It is noteworthy, however, that agential discretion goes much farther in the case of mutual aid than in that of gratitude. With gratitude, as we noted above, there is a specific individual, the benefactor, to whom the duty of gratitude is at least partially owed. But with mutual aid, by contrast, agents have extensive discretion to decide for themselves which of many potential beneficiaries they will in fact end up assisting. They could choose to provide aid to the impoverished and vulnerable individuals in remote countries that the Against Malaria Foundation is targeting through its efforts to distribute insecticidal nets; or they could help people in their immediate community who receive the support of a local food and housing organization. If we are to bring such duties within the ambit of the relational approach, then, we will need to reconcile this extensive discretion with the idea that the duties in question are nevertheless owed to some particular individuals, who can be understood in turn to have a claim, if not a specific moral right, to the agent’s compliance.

In setting the problem up in these terms, I am taking for granted what I believe to be our common-sense way of thinking about moral duties of mutual aid, as the paradigm case of imperfect duties to others. But this aspect of the conventional wisdom about them might be questioned. Adherents of the Effective Altruism movement, in particular, are inclined to challenge the idea that there is genuine agential discretion in cases of this kind to pursue projects of mutual aid that are less than optimal in their expected effects on the welfare of those who might benefit from them.20 There is of course much to be said for developing a critical understanding of the effectiveness of various aid programs and development efforts that it is open to both individuals and governments to support. Research into this question might help us to appreciate that some options are not above the threshold of effectiveness that would make it reasonable to include them in the set of charitable alternatives that we have discretion to pursue. To the extent the proponents of Effective Altruism deny that we have this discretion, however, it seems to me that they are simply shoehorning this aspect of our moral thinking—the part concerned with beneficence, as we might put it—into an essentially consequentialist mold. If we are not under a standing requirement to maximize the impartial good, then there is no reason to question whether we have agential discretion to pursue suboptimal projects in fulfillment of our imperfect duty of mutual aid.21

So my question is, how should we understand the discretionary duty of mutual aid within the framework of relational morality? Here is one possible answer. That agents are under such duties at all presumably reflects the fact that there are powerful objections that certain people have on their own behalf to principles that permit affluent agents to do little or nothing to assist those who are in extreme need. True, agents have objections in their own person to principles that require them to assist others in need. The most compelling of these stem from the requirements of living a recognizably individual human life; we have attachments to persons and projects that structure our activities at the most fundamental level, and that make it impossible to think of ourselves simply as conduits for the promotion of impersonal value.22

But of course those who are in a situation of acute need have even more powerful objections to principles that permit affluent agents to do little or nothing for people in their position. Thinking about the situation in these incipiently relational terms, it is plausible to suppose that acceptable principles would require that level of sacrifice from the affluent that would be sufficient to alleviate the acute need and dependency of the most vulnerable, if the principles in question were generally internalized and complied with by those in a position to help, while granting such agents discretion to decide for themselves, compatibly with their own projects and commitments, how exactly they will contribute.23 The role of agential discretion, in this context, would be to reconcile, as far as possible, the positive demands of beneficence with the need that individuals have to live a distinctive human life, one that reflects their own personal projects and interests. (Note that for all I have said so far, the resulting duties of mutual aid might be as demanding as you please; it is a further first-order question, to which I do not propose to enter here, precisely how onerous it would be for any given individual to live up to the moral requirements of mutual aid in a given case.24)

If this is the right way of thinking about mutual aid, however, then it seems we have a way of identifying the parties to whom the duties are owed. They would include all of those with acute needs who are in the class of potential beneficiaries of a given agent’s beneficent efforts.25 These are the people who have objections on their own behalf to principles that would permit agents to do little or nothing. We might therefore wish to say that agents owe it to all of the individuals in this class that they should live up to the principles of mutual aid that it would be unreasonable for anyone to reject; by the same token, each of these individuals has a claim against agents that they should comply with the principles in question.

These moral claims admittedly have some unusual features. For one thing, they are not claims that can be waived or alienated voluntarily by the persons who individually hold them. This seems to reflect the fact that each of the individual claimholders is a member of a class of potential beneficiaries of aid that includes many other individuals who are equally in a position of acute need; no one of them is authorized to waive entitlements that in any given case are liable to benefit other members in the class. This points to a further feature of the claims at issue that is even more peculiar. Not only are they not claims to any specific kind of performance on the part of the agent against whom they are held, since agents have wide discretion to determine for themselves which kinds of contribution they are going to make to alleviating the distress of those who are in dire need. They are not even claims that agents should do anything to help the claimholder in particular, since they could fully be discharged through discretionary efforts that end up assisting completely different members of the class of potential beneficiaries.

These peculiarities make it especially inapt to speak of assignable moral rights to assistance in cases of mutual aid. But it seems to me that moral claims, and the corresponding directed duties, may nevertheless intelligibly be ascribed to the parties in these cases, and that it can be illuminating to think in these terms. Affluent agents owe it to each of the individuals in the class of potential beneficiaries to do their fair share to provide needed assistance. And each of those individuals in turn has claims against individual affluent agents that they should so contribute. We are perhaps accustomed to thinking of moral claims as demands, compliance with which would redound to the benefit of the claimholder in particular, but I don’t see this as something that is built into the very meaning of a claim. A reflection of the relational structure implicit even in cases such as this one is the naturalness of the idea that affluent agents who do little or nothing to help out will be unable to justify their conduct to any of the individuals who are in the class of potential beneficiaries. Those individuals may accordingly be thought to have suffered a wrong or a moral injury, in virtue of the agent’s small but not insignificant role in a collective failure to avert the humanitarian disaster that has overwhelmed them.

This relational interpretation of duties of mutual aid focuses in the first instance, in ways characteristic of moral contractualism, on the situation of full compliance. The primary task for moral reasoning is to assess the comparative strength of individual objections to candidate principles, supposing the principles in question to be generally internalized and complied with by agents as a basis for their common social life together. This leaves open the different, but important question of what we as individuals are obligated to do under circumstances of merely partial compliance, including circumstances in which we ourselves have complied with the general demands of mutual aid, but many other people in a comparable position to us are doing little or nothing to help.

It is a striking fact about such situations that further incremental contributions by us, beyond what would be required from each if all were doing their fair share, would make a significant difference to the life prospects of some actual individuals who are subject to acute need. But do prospective beneficiaries have moral claims against us to go above and beyond in this way, given that many others in a comparable position to help out are doing so little? There are at least some considerations that seem to speak against this conclusion.26 If there are moral claims in play here, they would seem primarily to be held against the other individuals who are currently doing nothing. Those individuals need to step up to the plate and contribute their fair share to the collective project of alleviating the acute distress of the most vulnerable among us. This seems to be reflected in the emotional reactions that it would be natural for individuals in the class of potential beneficiaries to experience under the circumstances of partial compliance that I have described. They certainly have a grievance in this situation, something that would provide grounds for resentment and other forms of blame. But it strikes me as odd to suppose that these reactions should be directed at individuals who are already doing their fair share when there are so many in a similar position to help who are doing nothing, and when it is also the case that contributions by those agents would suffice to address the basic needs of the claimholders.27

Against this, it will be objected that there are plenty of situations in non-ideal theory in which people might have claims against us to emergency assistance, even though the emergency obtains only because of wrongs that have been committed by other agents, who are therefore already available to serve as objects of opprobrium. Think of the waves of desperate refugees currently fleeing the violent conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and other areas in the Middle East and North Africa. It seems to me correct to view their needs as creating salient opportunities for acts of mutual aid on our part; we may even have special responsibilities to help out in this situation, in virtue of our historical complicity in the political and economic conditions that generated the conflicts from which the refugees are now fleeing. Still, if we are already contributing our fair share to addressing the basic human needs of these vulnerable populations, there is a real question of whether we owe it to them to do more when so many others in our position are doing nothing.

There are admittedly some circumstances in which our moral responsibilities to help other people in need are not well conceived in terms of fair share contributions. Consider those familiar situations in which already conscientious individuals come across others in peril who can be rescued only by those on the immediate scene, where the rescue could be carried out at comparatively little cost to such proximate agents. The fact that individuals in this position have already contributed their general fair share to projects of mutual aid does not seem to release them from a responsibility to save imperiled strangers if they are now in a position to do so. Indeed, this conclusion appears to hold, even if there are other agents around who are equally in a position to rescue the imperiled strangers, and even if those agents have not yet done their fair share to contribute to mutual aid efforts over time.28

Examples such as this suggest that there may be separate principles that govern our ongoing contributions to collective efforts at mutual aid, and our duties in emergency situations that require a spontaneous response from individuals on the scene.29 The latter rescue situations seem to make demands on us that are fairly insensitive to questions about whether we have been doing our fair share to support ongoing programs to address the basic human needs of the most vulnerable. But the principles that govern these contexts define obligations that seem comparatively easy to understand in relational terms. There are specific individuals who have assignable claims against us to assistance, and who also stand to benefit directly if we honor those claims. Furthermore, the duties that we are under in these contexts do not grant us the kind of discretionary leeway characteristic of paradigm imperfect obligations. It is natural to conclude about these duties that they are owed to the imperiled individuals whose emergency plight we happen to be in a position to remedy.

But what about the situation of partial compliance with requirements governing our ongoing collective efforts of mutual aid, where we have already done our fair share, but many others in our position have done nothing? I admit that even here, there is residual pressure to think that already compliant individuals should do still more. After all, each incremental further contribution, beyond those they have already made, will cost them so little, and benefit others so much!30 I continue to think it is at least relevant to these contexts that there are many in a position to make the same additional contribution to the collective project who have not yet done so; given this aspect of the situation, it isn’t obvious that reactive and other forms of blame are rightly directed by the potential beneficiaries to the parties who have already contributed their fair share. But this is a question on which there is room for disagreement within the relational framework. Perhaps those in the position of potential beneficiaries have reasonable objections to principles for partial compliance contexts that permit compliant agents to make no further contributions. If so, the resulting, more demanding duties will still be directed in character, despite the discretion they seem to leave to the already compliant agents about how they are to be satisfied, and despite the fact that those to whom they are owed might not benefit directly from the actions the duties lead those agents to perform.

6.3. Numbers and Non-Identity

In this section, I shall address two classes of moral obligations that have seemed especially difficult to make sense of in terms of the claims of individuals. These are cases that involve the so-called non-identity problem, and cases in which the number of people who might benefit from our actions apparently has a direct bearing on what we ought morally to do. Each kind of case has attracted a vast and sophisticated literature, and there is no prospect of doing full justice to the issues within the brief compass that remains to me. My aim will be instead to highlight some resources of the relational approach, drawing on the preceding discussion, that seem to me to have been neglected in other treatments of these issues.

The non-identity problem arises in situations, involving our relations to future generations, that have the following two features: what we do (individually, or together with others) will foreseeably have a significant effect on the well-being of the people who will be alive in the future; but which particular individuals then exist will itself depend on how we now comport ourselves.31 Thus in cases involving resource depletion and global climate change, our current complacent behavior might be modestly beneficial to those who are currently alive, insofar as it frees up resources for present consumption that enhance our immediate well-being. But that same behavior will seriously degrade the natural environment that future generations of human beings will inhabit, in ways that can easily be predicted to have devastating consequences for the quality of the lives those future people will be able to lead. At the same time, it is also plausible to suppose that the significant changes in current lifestyles that would be necessary to avert these environmental effects would also make a difference to the identities of the people who will be alive in the future. The future individuals who will have to cope with the effects of our current complacent behavior would by and large not come into existence in the first place under a more environmentally responsible present regime, since identity, dependent as it is on genetic origins, is highly sensitive to even minor counter-factual perturbations in the behavioral patterns of ancestral generations.

The relational approach, as I have developed it, holds that the class of potential moral claimholders against us includes all of the people whose personal interests are apt to be affected, in one way or another, by the things that we do. This class clearly includes people who do not yet exist, but whose life circumstances stand to be shaped decisively by the behaviors that we and others of our generation choose to engage in. The personal interests of those future people provide grounds for objecting strongly to principles that would permit us to act in ways that predictably degrade the life circumstances they will be forced to cope with.32 But what exactly is the nature of those objections? Given the non-identity problem, it cannot be that we will have made them worse off than they otherwise would have been, since general compliance with alternative principles would have had the effect that those individuals never came to exist in the first place. It is tempting to infer that the moral objection to our current complacent behavior reflects an impersonal concern for the overall quality of the lives that are led by people in the future,33 rather than a specific concern about what we owe to each of the individuals who will then be alive.

This inference is too quick, however. It is true that the objections of future individuals to our complacent behavior cannot be couched in terms of a comparative conception of harm; they cannot complain that we have made them, as individuals, worse off than they otherwise would have been, since by hypothesis the behaviors determined by the general acceptance of alternative principles would have prevented them from coming into existence. But they also have noncomparative interests in obtaining those basic resources and opportunities that we all understand to be necessary for a flourishing human life, including adequate supplies of food and water and shelter, access to a basic education, freedom from constant social insecurity and displacement, and so on.

The pressing moral importance of issues such as global climate change and environmental degradation, it seems to me, stems from the thought that these behaviors are likely to lead to natural and social catastrophes for the members of future generations, affecting the noncomparative personal interests of those individuals in securing access to the necessities of a decent human life. By contrast, the noncomparative interests of the different people who would come to exist under a regime of responsible environmental and climatological stewardship do not ground a symmetrical objection to our behavior under that alternative regime. Under these conditions, it seems to me that the future people who will have to cope with our current complacent environmental and climate policies could be said to have moral claims against us as individuals, grounded in objections that can be lodged on their own behalf, to our current behaviors. This, despite their inability plausibly to claim that we have made them worse off than they otherwise would have been. It is the combination of a noncomparative conception of individual interests with an essentially comparative method of moral reasoning that yields relational resources for articulating our moral intuitions about cases of this kind.

The noncomparative notion of individual interests is not an innovation of mine; on the contrary, it is familiar from philosophical discussions of the non-identity problem.34 I emphasize its availability, however, because it enables us to understand, in relational terms, the most important contemporary cases that involve the non-identity problem. These are cases in which our collective behavior can be anticipated to have catastrophic effects on the actual individuals who will exist in the future, and in which alternative courses of action are available to us that would not have similar effects on the different future people who would exist if we chose them.

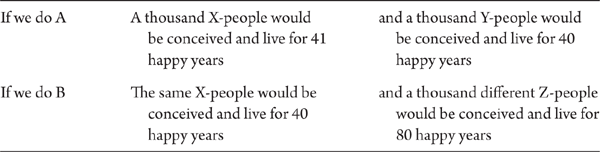

Consider, for instance, Derek Parfit’s recent critical discussion of contractualism and the non-identity problem, the burden of which is to show that contractualists must abandon the individualist restriction if they wish to develop plausible treatments of cases in which this problem arises.35 Parfit’s argument is advanced through the consideration of a series of highly artificial examples in which we are asked to choose between different distributions of a medical or other good across future populations. The moral urgency of his discussion of such cases, however, derives largely from frequent references to the important issues of global warming and environmental degradation. A characteristic passage is the following: “What now matters most is that we rich people give up some of our luxuries, ceasing to overheat the Earth’s atmosphere, and taking care of this planet in other ways, so that it continues to support intelligent life.”36 But as I have just explained, there are compelling ways of making sense of the serious moral concerns about these issues within the framework of the individualist restriction, so long as we operate with the noncomparative conception of harm and personal interests whose plausibility Parfit himself seems to acknowledge, and so long as we combine this conception with an essentially comparative procedure of moral reasoning.37

There are, of course, many different kinds of situation that involve the non-identity problem. One class of cases involves procreative decisions. Consider, for instance, an adult who confronts a choice between the following three options: (1) not having a child; (2) conceiving child A, who will live a life of moderate happiness; (3) conceiving a different child B, who will live a life that is very happy.38 It certainly seems permissible for the adult to choose the first option in this scenario, electing to remain childless rather than become a parent. But if she decides to bring a child into the world, some philosophers are convinced that it would be morally wrong for her to conceive child A rather than child B. Indeed, Parfit has argued that it would be just as wrong to choose (2) over (3) in a case of this kind as it would be to make the same choice in a different case in which the individuals conceived in (2) and (3) would be the same person, someone who would be made worse off by the choice of (2) over (3).39 If this is correct, then it is an intuition that would seem difficult to make sense of in terms of the relational approach I have been advocating. After all, the familiar reasoning goes, child A cannot have an objection on her own behalf to the adult’s choosing option (2), given that the life she is given in that scenario is one of moderate happiness, and that she would not even have existed if (3) had been chosen instead.

But this conclusion may again be too hasty. In standard presentations of cases of this general kind, it is stipulated that the reason why A’s life would achieve only a moderate level of happiness is that it would subject A to a serious “handicap,” albeit a handicap that is compatible with A’s having a life that is well worth living. But to bring it about that someone comes into existence with a handicap or a serious congenital ailment is arguably to bring it about that she will be harmed, in the noncomparative sense mentioned above. Our conception of a condition as a handicap or a congenital ailment presupposes a conception of the things that human individuals generally need in order to flourish, defining a noncomparative sense in which they have an interest in obtaining those very things in their lives. This noncomparative interest, in turn, might plausibly ground an objection, on A’s own behalf, to course of action (2), which foreseeably brings A into existence with the handicap in question. (Note that here, as in other cases with this structure, to have an individual complaint about the actions of an agent is not necessarily to prefer on balance that the agent should have acted otherwise.40) Options (1) and (3), by contrast, will not result in the existence of any new individual with a comparable objection. This seems to me sufficient to make sense of the intuition that there is a moral objection, couched in relational terms, to the agent’s doing (2) when options (1) and (3) are also available.

But suppose we modify the example, so that A and B have the same overall level of welfare as in the original scenarios brought about by actions (2) and (3), but it is not the case that A suffers from a handicap or a congenital ailment. It just happens that we can know in advance that unimpaired agent A will lead a life that is less happy overall than the life that would be led by B. In the vast recent literature on so-called population ethics, there is some tendency simply to assume that there must be a moral objection to bringing about future people whose welfare level is suboptimal (compared with the welfare of the different individuals who would come into existence if we acted otherwise).41 As Parfit wrote in his original discussion of these issues, “If in either of two possible outcomes the same number of people would ever live, it would be worse if those who live are worse off, or have a lower quality of life, than those who would have lived.”42 But if we accept this idea, it will be very tempting to conclude that it would be wrong for an individual to bring about the outcome that is in this way impersonally worse when alternatives are available to the agent that would have brought into existence a population of different individuals with a higher quality of life.43

This moral verdict, to be sure, cannot be accommodated within the framework of the relational account I have been developing in this book. But I think we should be deeply suspicious about the assumption that the verdict is an important datum for an account of interpersonal morality to accommodate. As many have observed, future individuals are not well thought of as vessels to be filled by us with happiness or well-being, and it is a serious distortion of our individual obligations to think that we have a duty to see to it that future populations exist that are as happy as it is possible for such populations to be.44 Our obligations in this area are better thought of as duties to ensure that humanity can continue under conditions that are conducive to the flourishing of future individuals, and these are duties that the relational account can comprehend.45 There may well be some cases of collective or administrative agency in which aggregative considerations of impersonal well-being have direct relevance to questions about how those in a position of authority ought to act. I believe that many of the artificial cases that exercise Parfit can be understood in these terms, as cases that mobilize intuitions about administrative or bureaucratic rationality. But this is a point that I shall set aside for the time being, returning to it in section 6.4 below.

In the meantime, I would like to take up, with similar briskness, the hoary question of whether the numbers count for moral deliberation. For ease of exposition, I shall concentrate on the very simple case already introduced in section 5.4 above, in which you are in a position to rescue some survivors of a shipwreck, at little risk to yourself, who are stranded on two different rocks. On Rock 1 there is a single survivor, while there are several on Rock 2, and it is clear that you cannot make it to both rocks to save everyone before the tide comes in and sweeps people away. Working within a relational framework that considers only the objections that individuals have on their own behalf to principles that would permit treating them in various ways, it appears that we cannot explain why it might be morally wrong to go to Rock 1 when it was also open to you to go to Rock 2, saving more.46

The first thing to note about cases of this kind is that it is open to a relational theorist to deny that there is a specifically moral objection to saving fewer rather than more.47 It would be wrong to save no one when you can rescue some at little risk to yourself, but we might bite the bullet and accept the conclusion that it is a matter of indifference to individual morality how many you save, precisely because you owe it to nobody in particular that more rather than fewer should be rescued. Furthermore, someone who takes this line could add that there might be compelling nonmoral reasons that speak in favor of going to Rock 2, where the greater number of survivors have sought temporary refuge.48 Given that there is no individual who has a moral claim against you to go to either rock, appreciation for the impersonal value of human life might provide a consideration, ancillary to relational morality, in favor of saving the greater number.49 On this approach, there is no moral obligation in the sense that is connected to individual moral claims to save more rather than fewer, but doing so is nevertheless something the rescuer has reason to do, in a more generic sense that does not ground a practical requirement or connect specifically to the claims that provide others with a basis for interpersonal accountability.

This is an important line of thought, and I want to come back to it in the following section. Before doing so, however, I wish to dwell a bit more on the case of the shipwrecked passengers on the two rocks. Is it really correct to think that there is no relational objection, couched in terms of the personal interests of the individuals whose lives are at stake, to saving the Rock 1 person rather than the several who are on Rock 2? Perhaps not. Remember that we are looking for principles for the general regulation of behavior that will be acceptable to everyone, and considering the consequences for individuals of adoption of the principles in question as a basis for social life. As we have seen, once a rescue situation has arisen, there will be particular individuals on the two rocks who are in a position to be assisted, and who will have precisely symmetrical individual objections to principles that permit the rescuer to save those on the other rock.

As noted in the previous section, however, we need perfectly general principles for dealing with situations of immediate rescue, where individuals find themselves uniquely positioned to avert human catastrophe through their direct efforts on the scene (acting either alone, or in concert with others who happen to be on the scene as well). Each of us, deliberating in abstraction from knowledge about which particular rescue situations of this kind might emerge, would seem to have personal reasons to reject some general principles for the behavior of rescuers in favor of others. In particular, it seems that we each have compelling objections on our own behalf to principles that permit rescuers to save fewer rather than more, at least when it is open to them to do so at comparably minor cost to themselves. The basic idea is that our own ex ante likelihood of being saved will be highest if rescuers are in general required to save as many as they are safely able to assist.

To think in these terms is to suppose that we are all liable to require the assistance of direct rescuers from time to time as we make our way through life, and that the shipwrecks and other events that make necessary assistance of this kind function as a kind of natural lottery, distributing individuals randomly across the various positions occupied by rescuees. True, the individual who ends up on Rock 1 in our particular rescue case would be relieved if you followed the policy of rescuing fewer that she herself had ex ante reason to reject. But this does not undermine the force of the ex ante objection to the general policy permitting rescuers to save fewer rather than more. As we have already seen, the later objections of the individuals on the two different rocks have already been determined to be inconclusive, insofar as they are countered by precisely symmetrical objections that can then be brought by other individuals to alternative principles.50 The idea is that, in this dialectical context, the fact that we all have ex ante personal reasons to reject principles permitting rescuers to save fewer might make it reasonable for each of us to reject such principles, as a general basis for regulating our interactions with each other.51

But what if there are individuals who know in advance that they are likely to end up in the smaller group when they need the assistance of rescuers?52 Such individuals, it seems, would have ex ante personal reasons to reject principles that require rescuers to save more rather than fewer. And their individual objections would neutralize the ex ante objections that each of the rest of us has to principles that permit rescuers to save fewer. There are two different scenarios that need to be distinguished here. First, individuals might know in advance that they will reliably find themselves in the smaller groups of people who need assistance in emergencies, because they choose to engage in risky activities that can be anticipated to have this consequence. (Perhaps they always swim out to remote areas that are far from the crowds, drawn in part to solitude and danger.) Under this scenario, the ex ante objections that the individuals would have to principles that require rescuers to save more rather than fewer seem undermined by the fact that their propensity to end up in the smaller group is the result of their own voluntary behavior. If they are concerned to increase their ex ante likelihood of being rescued in the event of an emergency, there is a way for them to do this compatibly with general policies for rescue situations that ensure that the ex ante interests of other agents are catered to as well.

Consider, next, agents who know in advance that they are likely to find themselves in smaller groups of potential rescuees through no fault of their own. Maybe they have grown up in comparatively remote and unpopulated regions of countries that are prone to earthquakes and tsunamis. Such agents would seem to have objections to principles that require rescuers to save more that are not in the same way undermined by their responsibility for the feature of their situation that generates those objections. The question to ask here is whether there are alternative policies, short of the adoption of general principles for rescue situations that would disadvantage others, that would address the special vulnerability of people in these remote regions. Perhaps we could make resources available to reduce their reliance on rescuers in the situations of danger that can be anticipated periodically to arise, by (for instance) securely depositing copious rations and emergency supplies in the remote villages. As long as measures of this kind are available, it would arguably be unreasonable for residents of such regions to reject principles requiring rescuers to save more rather than fewer, given the strong ex ante objections others have to alternative rescue principles.