UNDERSTANDING THE RATIONALE of modern terrorist organizations in general, and of radical Islamic terrorist groups in particular, provides a key to understanding their modi operandi, tactics, and strategy, and therefore to formulating an approach to combating them. Yet in responding to modern terrorism, Western decision makers often make ineffective and sometimes dangerous policy decisions, which can largely be attributed to a fundamentally misguided and mistaken evaluation of the rationale behind terrorist activities. Decision makers are often guilty of two common, albeit contradictory, errors in judgment.

The first of these errors is the misconception that terrorists themselves are irrational actors—“crazy people”—who thus cannot be effectively analyzed, evaluated, or understood.

1 Pursuant to this is the impossibility of predicting the behavior of an organization made up of such “crazy people”—a terrorist organization—or its response to counter-measures. In light of this misconception, counter-terrorism doctrine has developed primarily as a reflection of the calculations of the state that confronts terrorism, without reference to the enemy’s calculations or potential reaction. Such an approach is doomed to fail.

The second error is the mistaken assumption that a terrorist opponent makes decisions as would a Western decision maker, based on the same ethics, values, and rationale. This false assumption leads decision makers to believe it is possible to anticipate how a terrorist enemy will act when faced with certain pressures and state policies. In other words, they expect their terrorist enemy to behave exactly as a Western nation faced with similar conditions would. A Western decision maker who asks himself, “What would I do if I were in a similar situation? If I were attacked under the same conditions? What would I do if I were offered this or that compromise?” is not only assuming that his terrorist enemy will act the same way he would, but is also assigning the same rationale to very diverse terrorist organizations—be they local or global jihad groups, nationalist separatist groups, or the anarchist European terrorist organizations of the 1970s.

2If it is mistaken to assume that today’s terrorist organizations act irrationally, what is the rationale spurring them to action? What is the process that leads a radical organization to choose terrorist tactics? Following is a discussion of a dominant model of decision making, which can be used to explain the decisions of terrorist organizations.

THE RATIONAL CHOICE MODEL OF DECISION MAKING

The rational choice model seems to be the best model to explain the behavior of terrorist organizations. It is founded on the idea that “when faced with several courses of action, people usually do what they believe is likely to have the best overall outcome.”

3 In the words of Graham Allison, rationality is “consistent, value-maximizing choice within specified constraints.”

4 According to Mintz and DeRouen, the brevity of this definition belies its strength.

5 “This means that a few assumptions, put together, can explain a wide range of decisions.”

6 In layperson’s terms, a rational decision is made based on the course of action that will produce the greatest benefit at minimum cost.

As noted, a rational decision maker will identify and evaluate his alternatives and their implications, and then choose the alternative that maximizes his satisfaction with its outcome (an expression of utility).

7 In essence, the expected utility model assumes that people “attempt to maximize expected utility in their choices between risky options.”

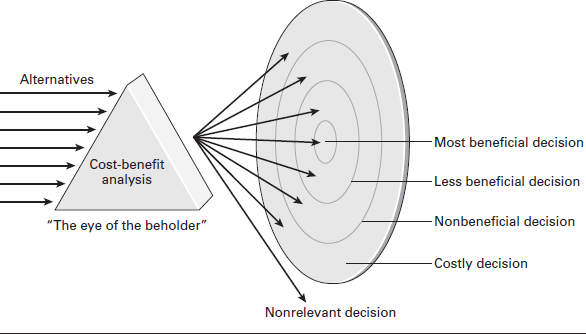

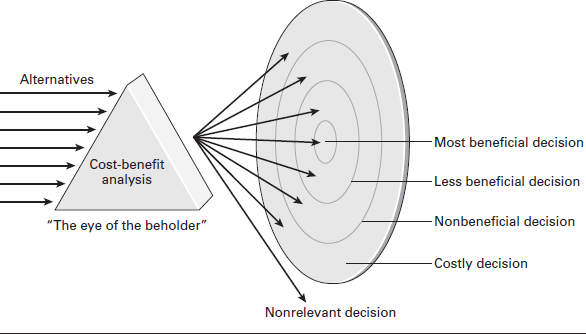

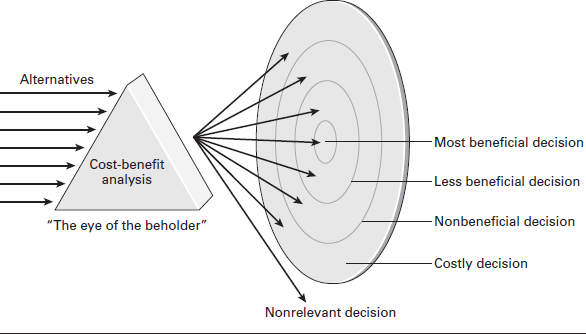

8Put simply, rational decision making is a process in which the decision maker conducts a cost-benefit analysis of alternative actions, and chooses the alternative he believes to be the most beneficial—that is, the alternative whose benefits outweigh its costs while achieving his objectives (

figure 7.1). Since terrorist decision makers follow this rational decision making process, we might agree with Bruce Hoffman that they are “disturbingly normal.” Far from fitting the popularized image of fanatic, insane murderers, as Hoffman explains, many terrorists make careful calculations and decide to perpetrate an act of terrorism as a completely rational decision.

9 Similarly, Martha Crenshaw has stated that terrorism is the expression of a political strategy constructed of rational, explainable processes. Modern terrorist organizations have a common preference: they choose terrorism from a range of alternatives, such that their decision to use violence is made willfully, for strategic and political reasons, and not due to psychological motives or disorders. From a theoretical perspective, the rational choice model has been equally defended and criticized. Renshon and Renshon have determined that “in general, the analytic process of the rational model should lead to better decisions although not always to better outcomes.”

10

FIGURE 7.1 A rational decision-making process

THE RATIONAL REASON TERRORISTS CHOOSE TERRORISM

Terrorists determine the efficacy of a given decision based on abstract strategic judgments that are themselves based on ideological assumptions.

11 Crenshaw presents a number of the generic advantages that terrorist organizations ascribe to terrorism. An organization chooses terrorism, explains Crenshaw, when other methods have proven ineffective or require extensive resources and time. Among its other advantages, terrorism brings its adherents the hope of political change by generating the revolutionary conditions required for mass uprising, undermining the authority of the regime it opposes and lowering public morale. By causing the government it opposes to impose oppressive measures, terrorism both attacks that opponent and reduces its legitimacy.

12The terrorist’s cost-benefit analysis and the choice it dictates are thus the result of a subjective judgment, which is influenced by the background of the decision maker who is making that judgment—that is, his culture, religious beliefs, ideology, experiences, and values. The relative cost or benefit that a terrorist assigns to his various alternatives will depend on this background, the morals it dictates—and his personality. For example, a terrorist leader whose actions are determined by his faith in a supreme protector and in divine or spiritual reward will perform a different cost-benefit analysis than will one who believes only in tangible material rewards. The importance attached to the concept of honor—the honor of women, parents, oneself—is also culture-dependent. For an Islamist terrorist leader, to kill or be killed to protect one’s honor may be perfectly acceptable, while for another no one’s honor is important enough to warrant risking lives.

The problem with incorrectly assuming that a terrorist opponent is an irrational actor, or misunderstanding his cost-benefit calculus and decision-making process, is that it can lead to the development of inept strategies for confronting terrorism, which may ultimately do more harm than good.

The unique threat posed by modern terrorism and global jihad, which exceeds that present during the Cold War, exacerbates this situation. However dangerous their nuclear arsenals, the United States and the USSR employed comparable rationales. The similarity of their cost-benefit analyses enabled them to discuss, negotiate, threaten or deter each other, and sometimes even to make concessions. Because the “language” of their rationale was mutually intelligible, they could communicate, “decoding” each other’s messages and setting reciprocally comprehensible boundaries to their conflict.

Given the current state of international affairs, states and terrorist organizations enter into conflict equipped with very different rationales—especially when the conflict is between jihadist Islamist terrorist organizations and a Western state. This situation is compounded by the inability of each party to understand the rationale, cost-benefit calculus, and decision making processes of the other. For example, Osama bin Laden was mistakenly convinced that the West operated and reacted primarily from considerations of material gain or gratification of the senses. At the same time, many in the West believed that Bin Laden and his colleagues were immune to moral considerations, and hence could be deterred only by military force. Under these circumstances, if one side makes a concession that it believes conveys a certain message, but the other side interprets that message incorrectly or even in a manner that contradicts what was intended, the concession will be worthless. Thus, there can be no real deterrence, negotiation, concessions, or even effective communication if the two sides to a conflict fail to understand each other’s rationale.

THE IDEOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS BEHIND THE TERRORIST’S RATIONALE

How, then, is it possible to understand the jihadist terrorist’s rationale and achieve the parity between enemies that existed during the Cold War? Martha Crenshaw has emphasized that even the most extreme behavior may contain an internal logic, and that there is no single suitable explanation for terrorism. However, to the extent that it is possible to identify consistent terrorist behavior, it is also possible to examine and understand it.

13 Any attempt to construct an effective strategy for countering terrorism requires just such an understanding; and this in turn presupposes extensive knowledge of the terrorist’s cultural and moral considerations, modus operandi, and decision-making processes. In other words, an effective counter-terrorism strategy must include messages that will be clear to the terrorist and congruent with his rationale. It also necessitates deploying a collection of diverse incentives, rewards, and costs that are appropriate enough to influence the terrorist’s cost-benefit calculations.

THE ROLE OF ROOT AND INSTRUMENTAL MOTIVATIONS AND GOALS

As noted, acts of terrorism are the result of a deliberate decision by a group of people to use a specific type of political violence to further their aspirations, be they ideological, religious, socioeconomic, or nationalist.

14 Some of a terrorist organization’s political goals are fundamental goals grounded in its ideology, while others are concrete, immediate goals fashioned in response to changing circumstances and time constraints. Despite the numerous and varied goals that terrorist organizations have striven to achieve throughout modern history, it is possible to arrive at a general classification, common to all or most terrorist organizations, of “root motivations and goals” and “instrumental motivations and goals.”

Root motivations are those causes and conditions that are often defined in an organization’s founding documents; they constitute its ideological basis and delineate its “strategic road map.” The specific goals that are derived from and meant to respond to an organization’s root motivations are that organization’s “root goals.” The root motivation of al-Qaeda, for example, is a return to a “pure Islam” and its dissemination throughout the world.

15 al-Qaeda’s root goal is the establishment of a global Islamic caliphate governed by

shari’

a (Islamic law).

16 Similarly, the root motivation of Hamas is based on imposing the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood on Palestinian society, including its political system.

17 The root goal derived from this motivation is the elimination of the State of Israel and its replacement by an Islamic Palestinian state on the entire territory of the former British Mandate.

18In contrast, instrumental motivations are those that arise in response to the changing circumstances in which the terrorist organization finds itself and the constraints with which it must cope. Sometimes, instrumental motivations are a concrete, pragmatic “translation” or interpretation of root motivations, devised because they are more relevant and attractive to the organization’s target population and hence more likely to efficiently promote its root motivations within a given society and time frame. These instrumental motivations are usually misusing and referring to real social and political concerns that represent—in the eyes of the terrorist organization’s constituencies—injustices that need to be corrected and maybe even justify the use of violence. At other times, instrumental motivations may differ from, or even ostensibly contradict, root motivations. Such instrumental motivations are meant to disguise an organization’s root motivations, thereby enabling it to indirectly promote its (true) root motivations in an environment that is unsympathetic to them.

Thus, for example, one of al-Qaeda’s most important instrumental motivations is to win the hearts of the Muslim masses, wherever they are. To fulfill its root motivation and reach its root goals, al-Qaeda must obtain the support of Muslims around the world. It could obtain this support through

da’

wa, by force, or by terrorizing anyone who does not accept its brand of Salafist Islam. However, al-Qaeda has chosen to win the support of the Muslim masses in another way, as well. It has devised a concrete, instrumental motivation: misusing ethnic, national, and territorial struggles between Muslims and rivals of other religions, such as the conflicts in the Middle East, Kashmir, Chechnya, Nigeria, Lebanon, and the Philippines. Each of these conflicts, which are both nationalistic and interreligious, can, and in many cases does, constitute an instrumental goal of al-Qaeda or one of its proxies and affiliates, adopted specifically to unite Muslims around the al-Qaeda root goal. While these instrumental goals, which are mainly based on local conflicts, do not contradict al-Qaeda’s root goal of establishing a global Islamic caliphate, they do pose the danger of deflecting attention and resources from the organization’s root goal, salvaging the chaff at the expense of the wheat. In other words, excessive emphasis on instrumental goals can jeopardize root goals: Focusing world Muslim attention on local conflicts to foment regime change and perhaps even territorial conquest will not necessarily culminate in actions that lead to the establishment of a global Islamic caliphate. The indirect strategy reflected in al-Qaeda’s instrumental goal, in this case, risks (re)directing attention from global to local jihad.

Hamas illustrates a somewhat different type of relationship between root and instrumental motivations and goals. One of that movement’s most important instrumental motivations is to gain the broad support of the Palestinian people for its ideology and goals. As indicated in the previous example, such a goal can be reached by winning hearts, exerting forceful tactics of persuasion, or deploying violence. In fact, since its inception, Hamas has not shied away from using any of these means.

19 However, thanks to the coexistence of multiple currents in Palestinian society, Hamas has chosen to win over the Palestinian people in part by setting the instrumental goal of “Palestinian unity.” Throughout its history, Hamas has engaged in direct conflict against one or another Palestinian faction: witness its use of extreme violence against Fatah to secure the Gaza Strip for itself in 2006. However, like Yasser Arafat in the 1990s (who was reluctant to confront Hamas and so refrained from disarming it, preferring instead to use its terrorist activity as a tool in his negotiations with Israel

20), Hamas chooses not to confront rivals or compatriots such as Salafist Palestinian groups. Instead, it allows them to act in the territories under its control; by thus trying to “ride the tiger,” Hamas attempts to control the intensity of the conflagration with Israel without bearing the direct consequences of Israel’s counter-terrorism efforts.

21 This policy has served the instrumental goal of Palestinian unity and thereby promoted the instrumental motivation of gaining Palestinian support. In this case, the instrumental goal of Palestinian unity does not oppose, contradict, or detract from the root goal of destroying Israel and establishing an Islamic Palestinian state in its stead.

How is it possible to determine whether a goal, be it stated openly or deduced from an organization’s actions, is an instrumental goal or a root goal? One of the most efficient ways to distinguish between the two is by assessing the consequences of attaining a given goal. For example, if al-Qaeda achieves its root goal of establishing a global Islamic caliphate, it will have realized its fundamental motivation and hence will necessarily change its essence—or vanish altogether. Similarly, if Hamas achieves its root goal of eliminating Israel and establishing an Islamic state in its stead, it will perforce cease to exist as a terrorist organization, metamorphosing into some other type of political entity. In contrast, if al-Qaeda achieves its instrumental goal of enlisting the support of the Muslim Nation (

ummah), its success will actually promote its root goal. Moreover, once this instrumental goal has been reached, circumstances are likely to change such that al-Qaeda will devise a new instrumental goal to further promote its root goal. In any case, achievement of this instrumental goal will not affect the essence of al-Qaeda.

In other words, root motivations and goals are static, whereas instrumental motivations and goals are dynamic, and are likely to change from time to time. Thus, for example, if the State of Israel is indeed eliminated and an Islamic Palestinian state established in its place, Hamas—having achieved a root goal—will change its essence—but al-Qaeda—having achieved an instrumental goal—will continue to exist but may replace this instrumental goal with a new one (such as giving primacy to one of the other local conflicts cited above).

Another example is provided by the instrumental goal that dictated Hamas’s policy regarding terrorist attacks during the 1990s: the goal of thwarting the Oslo peace process between Israel and the Palestinians. While Israel and PLO leaders, chiefly Yasser Arafat, were engaged in direct negotiations, the PLO generally refrained from perpetrating terrorist attacks inside Israel. In contrast, Hamas continued its terrorist campaign in Israel in an attempt to prevent negotiations from progressing, force Israel into reprisals, arouse antipathy among the public, and scuttle the peace process. And indeed, this instrumental goal was reached: with the death of the Oslo peace process in the 2000s, this goal ceased to exist.

Sometimes the general public and even terrorists themselves confuse an organization’s root goals with its instrumental goals. In some cases, a terrorist organization may deliberately present an instrumental motivation as if it is a root goal, in an effort to broaden its internal and external base of support by tapping into public sentiment and capitalizing on common concerns and interests. In other cases, an instrumental motivation may be designed to conceal or dilute the extremist, dogmatic nature of the organization’s root motivation. Needless to say, this confounds counter-terrorism efforts to determine which goals are at an organization’s ideological core and truly guide its actions and decisions, and which serve more ephemeral instrumental motivations, however important.

THE ROLE OF STRATEGIC AND CONCRETE INTERESTS

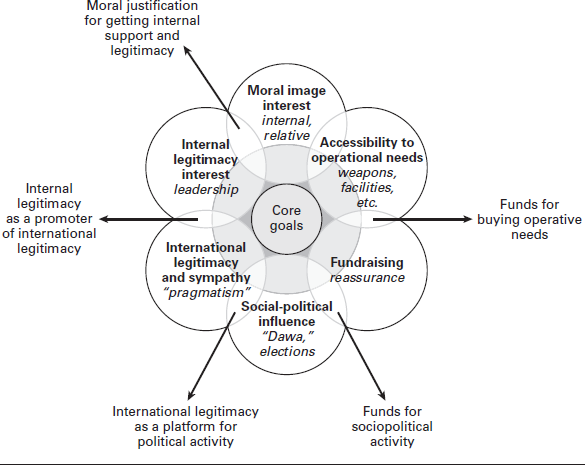

In addition to serving a terrorist organization’s root and instrumental goals, terrorist attacks are often meant to satisfy an organization’s strategic and concrete interests. Of myriad strategic interests, six can be identified, which are common to most terrorist organizations, as follows (

figure 7.2).

FIGURE 7.2 Strategic interests of terrorist organizations

Clearly, terrorists commit immoral acts, from intentionally harming human life and maliciously damaging civilian property to committing extortion. Their actions are often indiscriminate and almost always deliberately cruel, and they target civilians. Nevertheless, many terrorist organizations strive to present themselves to their members, population of origin, and the international public as moral and just. Indeed, terrorist organizations insist that ordinary citizens, both current followers and potential recruits, understand the “rightness and righteousness” of their cause. They want the public to perceive their actions as ethical and principled and to believe, with them, that violence is their only recourse against the unjust “superior evil forces of state and establishment.”

22Terrorist organizations employ various means and claims to justify their actions, especially when faced with heavy criticism. They use their root motivations and goals as both intellectual justification and moral guide to help their members cohere.

23 In confronting criticism from those outside, many terrorist organizations justify the killing of civilians as being a “greater good,” part of the need to deter an enemy nation from continuing its lethal actions.

24 al-Qaeda used this justification in responding to the demonstrations and public outrage that followed

25 a series of attacks on hotels in Amman, Jordan, on November 9, 2005, which resulted in the deaths of fifty-seven people, most of whom were Muslim Jordanians. As a result of the backlash, Jordanian-born Abu Musab Zarqawi, former leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, was forced to make a public apology. In an attempt to regain Jordanian sympathy, Zarqawi defended the attacks, stating that they were meant to target U.S. and Israeli intelligence officials—that is, legitimate targets—who were known to frequent these hotels. He stated: “We ask God to have mercy on the Muslims, who[m] we did not intend to target, even if they were in hotels which are centers of immorality.”

26 In the same breath, Zarqawi warned of further attacks in Jordan and urged Jordanians to stay away from hotels and military sites used by the United States, as well as from the embassies of nations that had participated in the invasion of Iraq.

27From time to time, the issue of intentional harm to civilians is discussed within terrorist organizations and on the Internet forums associated with them. Moral umbrage is usually quieted by claims that the use of violence against civilians is retaliation

28 warranted or caused by the attacked state,

29 a means that justifies the end—that is, the root goal. As such, any perceived moral dilemma is considered relatively insubstantial.

Despite this quick dulling of any pangs of conscience, it should be noted that the discussion within terrorist organizations of moral dilemmas—the very presentation of justifications—indicates that a range of strategic interests derives from an organization’s desire to consolidate a moral image for itself.

Achieving legitimacy in the eyes of the population of origin.

Most terrorist organizations purport to represent the interests of a particular segment of society with a distinct political, ideological, socioeconomic, ethnic, national or religious background. If a terrorist organization loses the confidence of the segment of society in whose name or interests it is acting, it will lose its legitimacy. As military mastermind and revolutionary Mao Tse-tung noted, insurgent groups must control the population they represent to be successful.

30 Whether given willingly or unwillingly, actively or passively, the support of that population is crucial to a successful guerrilla or terrorist campaign.

31 For this reason, terrorist organizations make multiple efforts to achieve legitimacy in the eyes of their population of origin, and thereby to maintain and broaden their base of support. One key way of doing this is by presenting a moral image.

Achieving international legitimacy, if not acclaim.

The complexity of running a terrorist organization—especially a hybrid terrorist organization—necessitates legitimacy and approbation among a population broader than that of the group’s origin. This is sought from states that assist terrorism, national minorities that are part of the organization’s “constituency,” and others who sympathize with the organization.

Achieving sociopolitical influence.

By investing resources in

da’

wa campaigns for the population of origin, an Islamist terrorist organization strives to achieve political and social influence and win the hearts and minds of its supporters. It may also enter the political system by participating in official elections to gain representation in government.

32Raising funds.

The ongoing logistical and operational activity, training and recruitment, salaries, and, above all, the organization’s da’wa activities all require significant funding. Terrorist organizations may alleviate their financial burden with generous assistance from states, communities, or wealthy donors who support and identify with their goals and their modus operandi. They may also raise funds through legal or illegal economic activity.

Obtaining operational resources.

Terrorist attacks require operational resources: a weapon suited to a particular task, safe houses, vehicles, forged documents, communications equipment, intelligence devices. Some resources can be purchased on the open market. Others, especially unique operational intelligence and assets, may be more difficult to obtain.

Of course, these strategic interests are not necessarily discrete; some share similarities, overlap, or may even be dependent on one another. Conversely, they may clash. Terrorist leaders may adopt a pragmatic approach, compromising some interests to gain others; for example, an organization may forfeit fund-raising through illegal means so as to preserve its international legitimacy. Curtailed fundraising may cause branches of an organization to compete for limited resources or may limit da’wa and political programs. This may in turn breed internal rivalry, weaken the organization’s leadership, or dampen the support of the population of origin.

Moreover, a terrorist organization may confront significant tension between its strategic interests and its root and instrumental goals. This is particularly true of hybrid terrorist organizations active in a political arena or seeking to raise funds internationally. When this happens, the organization may choose to conceal, disguise, or downplay the importance of its root goals. Hamas and Hezbollah are excellent examples of this. Both consider eliminating the State of Israel to be a root goal,

33 derived from a radical religious belief in a divine commandment. These organizations have consequently Islamized the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, transforming it from a national territorial conflict into a comprehensive religious one, and from a conflict that could have been resolved through compromise into a holy war.

THE SUBJECTIVE MORALITY OF TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS

As previously noted, the subjective considerations of a terrorist group are the result of the education, history, religion, culture, value systems, and worldview of its leaders. The West tends to see these as warped, inhumane, and absolutely immoral. Yet, interestingly, terrorist organizations actually ascribe great importance to issues of morals and ethics—and not only to presenting a moral image. Cracking the moral code of any given terrorist organization will clarify its considerations and decision-making processes, and enable counter-terrorism officials to more effectively neutralize, or at least minimize, the damage caused by terrorism.

It is important to understand the interdependence and hierarchy of a terrorist organization’s strategic interests, based on that organization’s moral considerations. For example, the need to consolidate and present a moral image may be an important precondition for attaining the support of the organization’s population of origin. This support is in turn essential for achieving international legitimacy, which is needed to support the organization’s political activity—which then reinforces its international legitimacy. Legitimacy breeds support, which facilitates the fundraising and acquisition of resources on which the organization’s ongoing operational activity depends.

Because the moral code of a terrorist organization is derived from a collective history, religion, and culture, terrorist leaders understand that to establish a conceptual platform of operations, they must invest considerable effort and resources in indoctrinating their members and supporters. In fact, indoctrination is a prism through which collective cultural and religious values pass en route to generating a terrorist organization’s moral code.

Terrorist attacks are therefore a result of the effort to promote an organization’s strategic interests, sometimes while also attaining its instrumental and root goals. A given terrorist attack may promote one or more strategic goals simultaneously or, alternatively, it may fulfill a concrete interest yet impede another interest or goal. An example of the latter is provided by the suicide attack on the Park Hotel in Netanya, Israel, in 2002. On a March evening—the eve of Passover and the occasion of the traditional Passover meal, or seder—during the height of the second intifada (uprising) that was to bury the Oslo peace process, Hamas deployed one of the worst suicide attacks Israel has ever sustained. Having shaved off his moustache and beard, donned a wig, and applied makeup, Hamas member Abd al-Bassat Ouda entered the dining room of the Park Hotel disguised as a woman, just as the hotel’s guests were eating the holiday meal. Ouda detonated the ten-kilogram bomb strapped to his body, killing himself and 30 of the hotel’s guests and injuring 140 people. This attack was only one of the twenty-three terrorist attacks perpetrated that March 2002 in Israel—one of the worst months of the second intifada, a month in which 135 Israelis lost their lives. In response, Israel launched “Operation Defensive Shield,” a comprehensive military campaign to conquer areas of Judea and Samaria that had been transferred to Palestinian autonomy as part of the Oslo peace process. Hamas intended the attack to achieve its instrumental goal of destroying the Israeli-Palestinian peace accord. It was also commensurate with Hamas’s root goal of eliminating Israel and establishing an Islamic Palestinian state in its stead. At the same time, the attack was meant to promote several of Hamas’s strategic interests, including increasing its influence and legitimacy among its population of origin—that is, the Palestinian people. However, while this abhorrent attack indeed bolstered Hamas’s status in Palestinian eyes, it harmed another of Hamas’s strategic interests; drawing widespread international condemnation and censure, the attack damaged Hamas’s image and status in Western public opinion.

A terrorist organization’s policy regarding terrorist attacks—that is, its decisions about the identity of its target, the date of attack, and the method of attack—is an outgrowth of its cost-benefit analyses and the influence of the entirety of its goals and interests. These considerations may explain the occurrence of a spate of terrorist attacks or a period of calm; in some cases, they may even serve as a means of forecasting trends in the extent and nature of terrorism.

A CLASSIFICATION OF THE GOALS OF TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS

The various goals of a terrorist organization can be classified according to four parameters: importance, source, time and transparency, as follows.

Importance

Importance. A goal’s relative importance to a terrorist organization is what distinguishes between root goals and instrumental goals. The root goals that spurred an organization’s establishment are therefore more important than instrumental goals, which may be changed over time or even renounced.

Source

Source. Who set the goal? Does it reflect external pressure on the organization? Was the goal set by a sponsoring state, or was it conceived by the founders or leaders of the organization? Usually, the source of a goal is indicative of an organization’s relationship with its sponsors and its level of dependence on them.

Time

Time. Is the goal fixed or mutable? Most organizations have both types of goal, which exist along a continuum between permanence and temporariness. For the most part, an organization’s root goals will be permanent; as noted, any change in them will signal, or lead to, a significant change in the organization. Permanent goals are therefore inflexible, even when circumstances dictate that they should not be. Conversely, the instrumental goals of an organization are temporary, designed to achieve concrete, short- or medium-term or ad hoc objectives. Changes in these goals do not affect the essence of the organization.

Transparency

Transparency. Are the terrorist organization’s goals overt or covert? Overt goals are those written into an organization’s charter, official documents, and publications, or voiced openly by its leaders. Covert goals are those which an organization keeps to itself, because they contradict either its publicly declared goals or the image the organization seeks to project.

A CASE IN POINT: GLOBAL JIHAD

An examination of the goals and causes behind the global jihad network, which is unofficially “headed” by al-Qaeda, will illustrate crucial differences between an organization’s root causes and goals and its instrumental causes and goals. al-Qaeda’s root cause is of an authentic religious nature, derived from a dogmatic, extremist interpretation of Islam that developed over time in several Sunni Salafist movements. al-Qaeda’s leaders and spiritual mentors have translated this root cause into the root goal of establishing an Islamic caliphate throughout the world, which will be governed by Islamic law (

shari’

a).

34al-Qaeda has expressed this root goal in interviews, public statements, and video and audio recordings. Its leaders have clearly indicated what they aim to accomplish through their campaign of global jihad. For example, Bin Laden charged that “the Islamic world should see itself as one seamless community, or

umma, and … Muslims [are] obliged to unite and defend themselves.” He advocated that Muslims find a leader who would unite them in establishing a “pious caliphate” governed by Islamic law and follow “Islamic principles of finance and social conduct.” Before the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, Bin Laden repeatedly cited the Taliban regime there as a model of this ideology.

35 In 2004, he indicated that these and other similar statements should be referred to as “primary sources” by anyone seeking to understand al-Qaeda’s ideology and demands.

36al-Qaeda also clearly defined its objectives in a January 2005 audiotape and a June 2005 video message in which Osama bin Laden’s deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, identified the organization’s “three foundations” or root goals: (1) “the Quran-based authority to govern,” that is, the creation of an Islamic state governed solely by

shari’

a (Islamic law); (2) “liberation of the homelands,” or “the freedom of the Muslim lands and their liberation from every aggressor”; and (3) “the liberation of the human being,” i.e., the freedom of Muslims to criticize and, if necessary, “resist and overthrow rulers who violate Islamic laws and principles.”

37It proved quite difficult to market such controversial root goals, both throughout the Muslim world and especially among the general global public. In striving to overcome this difficulty, al-Qaeda’s leaders have highlighted instrumental causes with potentially wider appeal—specifically, various territorial disputes that involve Muslims—deriving from them the instrumental goals that are often embodied in regional conflicts. This enables global jihad’s leaders to avoid the ramifications of direct confrontation with Arab and Muslim leaders, whom they regard as infidels. These deceptive but more palatable instrumental causes in turn spur radicalization in the Muslim world and the growth of the global jihad network, gaining it legitimacy by exploiting both the frustrations of Muslims and the conflicts in the Muslim world that are otherwise unrelated to the mission of al-Qaeda and global jihad.

One prime example of the ensuing confusion between root and instrumental causes and goals is provided by al-Qaeda’s references to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Policymakers, pundits, and laypeople around the world are today convinced that this conflict is the primary reason for the growth of the global jihad movement and the spread of Islamic radicalization—in fact, that it is the source of all Middle Eastern conflict.

38 And why shouldn’t they be? al-Qaeda’s leaders have said as much, often citing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as the wellspring of al-Qaeda’s grievances and the motivation for its attacks. In an October 2004 video statement, Osama bin Laden explained the “story” behind the events of 9/11, noting that the idea for the attack occurred to him “after [the Palestinian-Israeli conflict] became unbearable and we witnessed the oppression and tyranny of the American/Israeli coalition against our people in Palestine and Lebanon.”

39However, most anti-Israel rhetoric has emerged in statements made by leaders of the global jihad network more recently; since its first appearance, it has varied in intensity and prominence in the organization’s statements and materials. In fact, at the time of al-Qaeda’s establishment and throughout the 1990s, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict was not cited as a primary or even secondary reason for its founding or activities. The shift in rhetoric and increased focus on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict began only in the late 1990s, and primarily after 9/11.

It was in February 1998 that Osama bin Laden and his compatriots announced the establishment of the “World Islamic Front for Jihad against the Jews and Crusaders,” which has come to define the struggle of global jihad against its two main enemies: the United States and Israel. The announcement appears to have occurred only as leaders of the global jihad movement identified the Palestinian-Israeli conflict as a cause that would unite Muslims throughout the Arab and Western worlds. Indeed, some have argued that al-Qaeda’s commitment to the Palestinian cause actually “waxes and wanes” depending on its public relations considerations.

40Today, Muslim activists and supporters from a range of different—and often even rival—Muslim sects and factions are in most cases united in their stance vis-à-vis the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This stance has been fueled by widespread, transnational anti-Israel indoctrination, as well as by biased media coverage that emphasizes the suffering of the Palestinian people and ignores the Israeli perspective and narratives. Bin Laden and his compatriots gradually tapped into this cause, realizing that anti-Israel rhetoric and reasoning would strike an emotional chord with potential followers and supporters. This strategy subsequently gave their actions further justification, legitimizing their terrorist activity in the eyes of their followers and supporters.

Blaming Israel and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict for global jihadist terrorism, Islamic radicalization, and other world problems has become common practice. From academic scholars to policymakers, the story is the same. According to the claims of global jihad, Israel appears to be one of the chief causes, if not the main cause, of the radicalization of Muslim youth throughout the world. But is the Palestinian-Israeli conflict really at the root of the growth of global jihad and radicalization processes in the Muslim world? Were the attacks of 9/11 carried out because of Israel’s seizure of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967? If we place this question in a broader context, we might ask whether the territorial disputes in Kashmir, the Balkans, Chechnya, the Philippines, or South Thailand have given rise to global jihad. Asked thus, the answer to the question is simple: they have not.

None of these disputes, “not even” the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, is the root cause of the existence of al-Qaeda and global jihad. The global jihad movement is merely effectively exploiting these regional conflicts as instrumental causes and goals, which fire Muslim emotions and justify violent actions that in turn can be used to recruit and indoctrinate Muslim youth.

The United States was not attacked on September 11, 2001, because it supports Israel. Neither was it attacked because of its military presence and activities in Iraq or Afghanistan, which the attacks pre-dated. The United States was not attacked because of anything it has done; it was attacked because of what it is. Around the world and particularly in the Muslim world, the United States is the spearhead of Western society, a symbol of liberal freedoms, civil society, human rights, women’s liberation, and enlightened democracy—all of which are concepts that are anathema to al-Qaeda and its allies. This is the reason the United States and its Muslim and Western allies have been and will continue to be the ultimate enemies of global jihad.

As for the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, what would happen if Israel were to reach a peace agreement with the Palestinians in the near future? Would that settle the grievances of al-Qaeda and global jihad? What would happen if Israel were to be defeated militarily and annihilated by its enemies? Would that lead to the elimination of al-Qaeda or the cessation of radicalization in the Muslim world? It is clear that the answers to these questions are negative. Not only would none of these events stop the radicalization process, but they would most likely be regarded as a victory for radical Islam over the perceived vanguard of the Western world. Such a victory would simply provide the incentive for an escalation in radical Islamic activity in the Middle East and its penetration even deeper into the West.

Will the departure of the United States from Afghanistan lead to the breakup of the global jihad network? Here, too, the answer is negative. Global and local jihadists will try to seize territories where government control has been undermined, and bring about fundamentalist Islamic revolutions. They will try to establish local Islamic caliphate states ruled by Islamic law (

shari’

a), with the intention, at a later stage, of uniting these caliphate states to bring about the hoped-for change worldwide, as local jihad merges with global jihad. In fact, this process has already begun and even intensified, through the revolutions of the Arab Spring.

If the Palestinian-Israeli conflict or problems in Chechnya, Kashmir, or the Balkans are resolved, global and local jihadists will instigate other violent conflicts and disputes between Muslim communities and those of other religions and cultures around the world. Global jihadists and al-Qaeda wish to fan the flames of frustration and ensure that Muslim youth everywhere remain vulnerable to incitement. Regional conflict, whether instigated or “adopted” by al-Qaeda, generates the instrumental causes that seem to justify the brutal terrorist attacks of jihadists.

It is as instrumental causes that territorial conflicts play such an important role in the strategy of global jihad, serving as an effective tool in the hands of al-Qaeda and its affiliates. They therefore require a just solution, first and foremost for the benefit of the people affected. While the resolution of these conflicts will at least temporarily hamper Islamic jihadist incitement and indoctrination, the West should never allow itself to entertain the illusion that this will solve the problem of global jihad and radical Islam, or eliminate al-Qaeda’s root causes. Unless the West addresses these root causes—primarily, a dangerous, radical interpretation of Islam and internal processes within Muslim society—real or adopted instrumental causes will at most shift to new arenas, focus on different immediate needs, or appeal to different sectors of (Muslim) society. In other words, reasons, justifications, and pretexts may change, but the phenomenon will not disappear.

Moreover, the phenomenon will only worsen as long as moderate Muslims continue to build a world of simplified justifications that absolve them from taking the difficult, painful responsibility for addressing the true root causes of global jihad. At present, Muslim moderates delude themselves and mislead their Western colleagues by placing the blame for the dangerous process occurring within Muslim society on others—that is, for intentionally confusing root causes with instrumental ones. As long as moderate Muslims continue to stick their heads in the sand and ignore their obligation, as Muslims, to restore honor to their religion through education and tolerance, they will continue to face a growing nightmare. Their coreligionists, especially those of the younger generation, will lose all sense of temperance as they form a barrier to be pressed against in the struggle between Islamic fundamentalism and the rest of the world.

This chapter has attempted to highlight the importance to counter-terrorism of accurately identifying and distinguishing between the root causes and the instrumental causes of a terrorist organization, and of understanding the complicated combination of these goals and their hierarchy, synergy, and overlap, or the contradictions and tensions between them.

Chapter 8 will discuss the practical aspects of a terrorist organization’s rationale: What are the considerations and operational needs informing the decision to engage in terrorism or guerrilla warfare? What triggers the launching of a terrorist attack?

Importance. A goal’s relative importance to a terrorist organization is what distinguishes between root goals and instrumental goals. The root goals that spurred an organization’s establishment are therefore more important than instrumental goals, which may be changed over time or even renounced.

Importance. A goal’s relative importance to a terrorist organization is what distinguishes between root goals and instrumental goals. The root goals that spurred an organization’s establishment are therefore more important than instrumental goals, which may be changed over time or even renounced. Source. Who set the goal? Does it reflect external pressure on the organization? Was the goal set by a sponsoring state, or was it conceived by the founders or leaders of the organization? Usually, the source of a goal is indicative of an organization’s relationship with its sponsors and its level of dependence on them.

Source. Who set the goal? Does it reflect external pressure on the organization? Was the goal set by a sponsoring state, or was it conceived by the founders or leaders of the organization? Usually, the source of a goal is indicative of an organization’s relationship with its sponsors and its level of dependence on them. Time. Is the goal fixed or mutable? Most organizations have both types of goal, which exist along a continuum between permanence and temporariness. For the most part, an organization’s root goals will be permanent; as noted, any change in them will signal, or lead to, a significant change in the organization. Permanent goals are therefore inflexible, even when circumstances dictate that they should not be. Conversely, the instrumental goals of an organization are temporary, designed to achieve concrete, short- or medium-term or ad hoc objectives. Changes in these goals do not affect the essence of the organization.

Time. Is the goal fixed or mutable? Most organizations have both types of goal, which exist along a continuum between permanence and temporariness. For the most part, an organization’s root goals will be permanent; as noted, any change in them will signal, or lead to, a significant change in the organization. Permanent goals are therefore inflexible, even when circumstances dictate that they should not be. Conversely, the instrumental goals of an organization are temporary, designed to achieve concrete, short- or medium-term or ad hoc objectives. Changes in these goals do not affect the essence of the organization. Transparency. Are the terrorist organization’s goals overt or covert? Overt goals are those written into an organization’s charter, official documents, and publications, or voiced openly by its leaders. Covert goals are those which an organization keeps to itself, because they contradict either its publicly declared goals or the image the organization seeks to project.

Transparency. Are the terrorist organization’s goals overt or covert? Overt goals are those written into an organization’s charter, official documents, and publications, or voiced openly by its leaders. Covert goals are those which an organization keeps to itself, because they contradict either its publicly declared goals or the image the organization seeks to project.