AS NOTED IN chapter 7, the operational strategy of any given terrorist organization and the scope and characteristics of its terrorist attacks are an outgrowth of its core ideology and, more specifically, its root goals and instrumental goals, in concert with its strategic interests. Nevertheless, the specific decision to conduct a terrorist attack can be understood only by also analyzing the practical and operational considerations underlying it.

THE DECISION TO ENGAGE IN TERRORISM OR GUERRILLA WARFARE: PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND OPERATIONAL NEEDS

The operational strategy of any terrorist organization governs not only whether or not it will launch a terrorist attack or guerrilla campaign, but also the structure and characteristics of the planned attack. These characteristics include the following:

The target or targets.

The target or targets. This includes the type of target—e.g., civilian or military, carefully chosen or random—and its location, in enemy territory or elsewhere.

The timing.

The timing. Should the attack be conducted during the day or at night, at rush hour or during a lull in traffic, on a symbolic day such as Memorial Day or Independence Day or on a random weekday?

The message to be conveyed by the attack.

The message to be conveyed by the attack. Should the attack be accompanied by a frightening message that will intensify the dread and anxiety of the target population? Should it send a message of deterrence in retaliation for a counter-terrorism campaign?

The scope of the attack.

The scope of the attack. Will it be a large-scale attack, killing and injuring many people? Or will it be a small-scale attack? Should the attack be one sporadic incident or part of an ongoing campaign of guerrilla warfare or terrorism?

The type of attack.

The type of attack. What methods will be used in the attack? Will it be a suicide attack, a hijacking, a bombing?

Together and separately, each of these characteristics determines the effectiveness of a terrorist attack or guerrilla campaign in advancing an organization’s root and instrumental goals and interests. For example, if one of an organization’s instrumental goals is to prevent peace and reconciliation, an attack may be timed for the eve of the signing of a peace agreement or to interfere with a gesture of reconciliation. Similarly, if one of the organization’s instrumental goals is to isolate its opponent state, it may choose to commit an attack in the territory of an uninvolved state that maintains friendly relations with the opponent state, in the hope of jeopardizing their friendship.

1 In other cases, a terrorist organization may find that hijacking, kidnapping, and ransoming hostages are useful ways of fulfilling its strategic interests of fundraising, or liberating imprisoned terrorists, for example.

In addition to advancing a terrorist organization’s root and instrumental goals, terrorist attacks often also have a more concrete end: they promote one of the organization’s practical and operational needs. These needs can be divided into three groups, as follows:

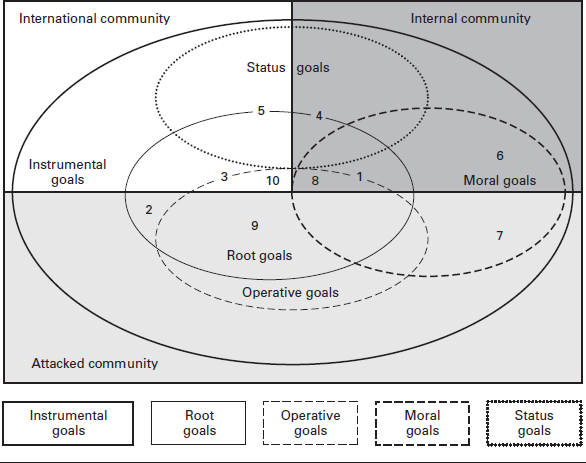

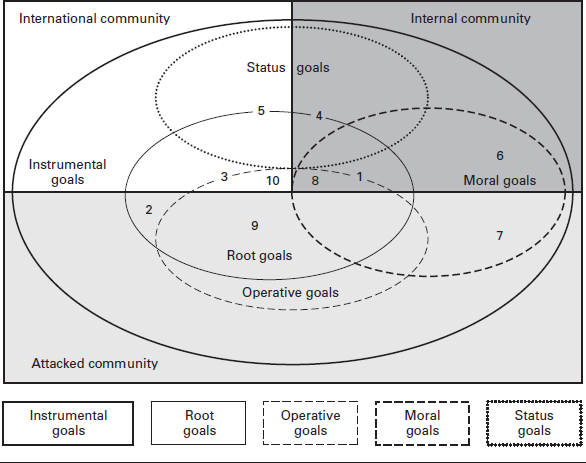

1. Moral goals: attacks that boost morale. Terrorist attacks of this type are designed as much to galvanize an organization’s population of origin (6 in

figure 8.1) as to demoralize its opponent’s population, instilling fear and anxiety so as to intensify terrorism’s psychological impact (7).

2. Status goals: attacks that improve the organization’s status. These attacks are meant to raise the internal or international status of a terrorist organization and damage the enemy state’s prestige and legitimacy. For example, if several organizations are competing for the support of a given population of origin which they purport to represent, an organization may be particularly keen to improve its status among that population (4). Or an organization may wish to improve its status in the eyes of third-party actors that are not involved in the conflict (5), but whose sympathy with the organization’s struggle may advance its root or instrumental goals.

3. Operative goals: attacks that help keep the organization operational. Attacks of this sort are designed to help an organization obtain the resources it needs to maintain its activities. Hijacking or kidnapping for ransom or for the release of imprisoned members of the organization are examples of this type of attack, as are attacks that exemplify a behavioral model—the martyr’s lifestyle—for the (Muslim) population of origin, thereby generating recruits and funds (8). At the same time, these attacks achieve the operational goal of disrupting the lifestyle of the opponent population and damaging the opponent state’s tourist industry (9). Lastly, vis-à-vis the international community, the operational goals of a terrorist organization may include goading states into “buying quiet”: in return for refraining from attacks in a given state or from attacking the interests of that state beyond its borders, a terrorist organization may expect administrative freedom in that state, or tangible assistance (10).

FIGURE 8.1 The goals and interests of terrorist campaigns

Terrorist attacks are not just aimed to promote practical and operational needs. At the same time, they are also meant to transmit one or more messages to the following three target audiences:

The internal community.

The internal community. That is, the terrorist organization’s population of origin, including its members and supporters, and the people the organization purports to represent.

The attacked community.

The attacked community. That is, the opponent population or enemy state—an ethnic group, a religious or cultural minority, followers of a certain ideology, or a political group.

The international community.

The international community. That is, world public opinion, especially that of liberal and politically engaged third-party citizens, who traditionally support the perceived “underdog.”

Figure 8.1 classifies the goals and interests that terrorist organizations strive to achieve by launching terrorist attacks.

To illustrate: al-Qaeda conducts terrorist attacks to advance its root goal of establishing a global Islamic caliphate. Its attacks are meant to weaken regimes and individuals who are “unbelievers” (

kuffar). Indeed, the attacks mounted by al-Qaeda resonate among the opponent community, the community of origin, and the international community. It is interesting to note that a central problem facing al-Qaeda is the somewhat blurred distinction between its community of origin and its opponent community: Although al-Qaeda purports to represent Muslims wherever they may be, it also reviles Muslims who do not share its fundamentalist interpretation of Islam. This tension is felt whenever al-Qaeda’s terrorist attacks cause random or intentional harm to Muslims, thereby undermining its ability to reach its root goal.

The terrorist attacks perpetrated by al-Qaeda and its affiliates in Western countries are designed primarily to achieve its instrumental goal of deterring Western nations from participating in Islam’s internal struggle by assisting moderate Muslims. By targeting the United States in particular, al-Qaeda aims to present it as a common enemy of Muslims everywhere, and thus to inspire young Muslims to join al-Qaeda’s ranks. To intensify the urgency of the need to attack the West and its spearhead—the United States—al-Qaeda and its affiliates present their terrorist activity in defensive terms, as if they are protecting Islam from a great evil that is threatening to destroy it.

2WHAT TRIGGERS THE LAUNCHING OF A TERRORIST ATTACK?

As explained above, root and instrumental goals, strategic interests, and practical needs inform the process of decision making that leads to the perpetration of a terrorist attack or campaign. In addition, a terrorist attack may be the direct or indirect result of immediate, concrete triggers. Specifically, at any given time, internal or external influences may push an organization’s leadership to initiate a terrorist attack. These influences will be exerted either from the top down or from the bottom up, as shown in

figure 8.2.

TOP-DOWN EXTERNAL TRIGGERS

Top-down external triggers are those processes that originate outside of a terrorist organization, sometimes in the international arena, which influence the organization’s considerations. They may include the following:

International political developments ranging from conflicts to peace processes, and including specific events such as the eve of the signing of an agreement, the time preceding the implementation of a signed agreement, meetings between representatives of adversaries; the evolution of international (or local) crises and wars; counter-terrorism and military operations against the terrorist organization, which have a “boomerang effect,” i.e., that motivate a counter-attack

3; summit meetings of heads of state; political assemblies.

Memorial days, or the commemoration of meaningful events in the history of the terrorist organization, such as the day the organization was established, the anniversary of a significant attack carried out by the organization, the anniversary of the death of one of the organization’s leaders or prominent members, religious ceremonies and festivals.

Regional and international events that attract large crowds and receive extensive media coverage, such as the Olympic Games, the Boston Marathon, or the World Economic Forum at Davos.

Pressure or demands from a sponsor state, such as that an attack be perpetrated in exchange for aid, or that an attack advance the sponsor’s interests and worldview—even if these contradict or discount the interests and goals of the terrorist organization itself.

FIGURE 8.2 Factors that may trigger a decision to commit a terrorist attack

BOTTOM-UP EXTERNAL TRIGGERS

This type of external trigger refers to those influences originating in the organization’s local arena. Such triggers include the following:

Pressure from the terrorist organization’s population of origin. Most terrorist organizations are receptive to the grievances, demands, and feelings of their “home” population. At times, an organization’s constituency may help to curtail its activities. At others, a constituency incited by hatred, anger, and a desire for revenge may spur an organization to action. It is important to note, also, that external bottom-up influences may not necessarily be based on concrete evidence of violent sentiments among the organization’s population of origin, but rather on the perception of the organization’s leadership, which may not necessarily reflect reality.

Competition among rival terrorist organizations that claim to represent the same population. In such cases, the decision to launch a terrorist attack may be designed to demonstrate to the population of origin that a given organization is more determined and capable than its rivals.

One-upmanship: that is, a response to a terrorist attack by a rival organization, which is meant to imitate, best, or “ride on” the success of the competitor.

4TOP-DOWN INTERNAL TRIGGERS

Internal triggers are those processes and influences that originate within a terrorist organization, as described below. Top-down internal triggers are initiated by the leaders of the organization and may include the following:

An attempt to raise the morale of the terrorist organization’s members.

An impetus from the organization’s spiritual leadership, be it ideological or religious in nature. Even in the absence of hierarchical compliance, an organization’s operative leadership may be guided and strongly influenced by its spiritual leadership, because of its inherent appreciation of the latter’s authority.

BOTTOM-UP INTERNAL TRIGGERS

Pressures and demands on an organization’s leadership that originate in the field, and which climb the organization’s hierarchical ladder until reaching its decision makers, constitute bottom-up internal influences.

The simple fact of opportunity, created, for example, by the presence of a member of a terrorist organization who has particular skills or capabilities, or by the accessibility of a potential target.

Internal competition among an organization’s leaders, units, or members.

A desire to test the reliability and determination of a member whose peers suspect him of collaborating with an enemy state.

THE CROSSROADS OF TERRORISM DECISION MAKING

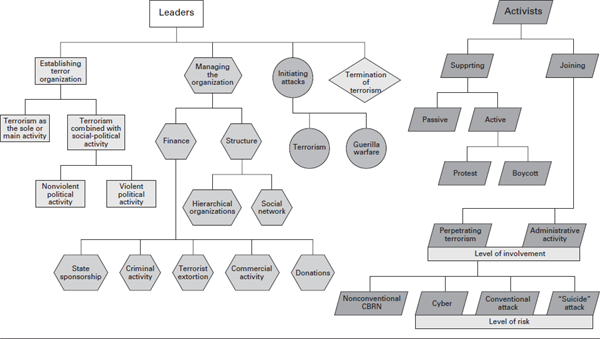

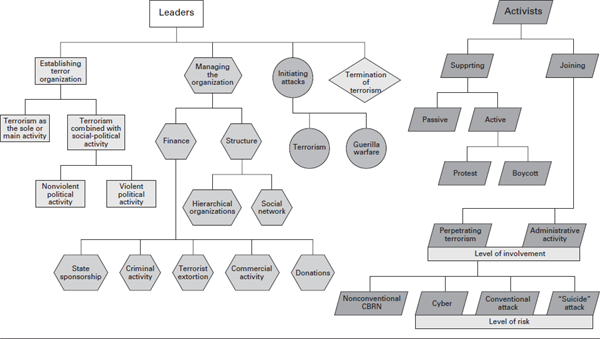

The decision to launch a terrorist attack is one of many decisions that terrorists and their leaders make, from the time a terrorist organization is established until it ceases to exist.

Figure 8.3 presents the decision-making crossroads reached by an organization’s founders, leaders, and members. As shown in

chapter 7, decisions are usually made in a rational manner at least by the organization’s leaders, who calculate the advantages and disadvantages of various alternatives. The alternative chosen is the one whose advantages outweigh its disadvantages, in the subjective opinion of the decision maker.

The first decision made in any terrorist organization is the decision to found it. An organization’s founders share a political, cultural, or religious worldview and strive to achieve common root goals. At a certain point in time, they will reach the first decision-making crossroad: Should they try to achieve their root goals by using nonviolent political measures, or would the use of violence and terrorism advance their goals more efficiently? If the founders conclude that the best response to their common yearnings is to commit terrorist attacks, they will then make the transition from being a band of people with similar political aspirations and goals to becoming a terrorist organization. Subsequently, the founders will find themselves at another decision-making crossroad: Will terrorism be the central or sole activity of the organization they have established, or will they also engage in other types of activity, such as politics? If so, should they become a hybrid terrorist organization?

FIGURE 8.3 Decision-making crossroads in terrorist organizations

If they decide to also engage in political activity, the next decision-making crossroad they will reach concerns what form this activity will take. Will the organization become involved in politics through proxies who identify with its ideology and goals, or through its members? Will the organization form a political arm (such as Hezbollah or Hamas) or will it conduct political activity via a separate apparatus, such as a political party, that is an independent entity and that denies any connection to the terrorist organization (as did the IRA)? The answers to these questions will be influenced inter alia by the attitude and reaction to the terrorist organization’s political activities of the host state and the international community.

Proximate to an organization’s establishment, its founders will also have to decide on its desired structure—the one that will best suit its goals and modus operandi. This structure may be hierarchical, with a clear command and control configuration, or it may be a network of loose social connections. The organization’s structure will in turn determine its nature. Will it be a “skeleton organization” of just a few activists, or will it be a “popular organization” that grows and expands until it numbers hundreds or thousands of members?

The organization’s leaders will also have to decide how they prefer to finance its activity. What will be its sources of revenue? Should they look for a state’s sponsorship? If so, are they willing for the organization’s activities to be subordinate to that state’s interests? The leaders may decide to concentrate on fundraising, accepting donations from supportive communities. Or they may choose to (also) raise funds through criminal activities such as forgery, fraud, theft, extortion, counterfeiting medicine and other products,

5 or drug manufacture and trafficking. They may choose to raise money by kidnapping and ransoming hostages; by hijacking airplanes, ships, or buses; or by extorting protection money. Lastly, they may choose to use a combination of all or some of these activities.

Another key decision-making crossroad is that at which the leaders of an organization must decide whether to initiate and commit a terrorist attack or guerrilla campaign, and the nature of the targets of attack (civilian or military).

A different type of decision must be made by the organization’s members, beginning with whether they wish to become affiliated with the terrorist organization. Those who decide in the affirmative perforce identify with the organization’s causes and goals; they then must decide whether to formally join the organization, or merely to support it—and if the latter, whether to do so passively or actively. Passive support may involve publicly defending the organization’s activities and promoting its message and goals in interaction with peers and relatives, or through social or traditional media. Active support may entail participation in protests, riots, and demonstrations on behalf of or in support of the organization, sending funds to the organization, or sheltering the organization’s members. Active operational support might involve helping terrorists move from one place to another, or obtain weapons.

A supporter who decides to formally join a terrorist organization may at some point have to decide the level and nature of his involvement in it.

6 For example, he may choose partial membership in the organization’s militia, or full membership, including involvement in administrative activity or in planning, preparing, and perpetrating terrorist attacks. If he decides to participate in terrorist attacks, he will have to decide the degree of risk he is willing to take. As a rule, active involvement in any kind of terrorist attack is risky. However, different kinds of attack expose the perpetrator to different degrees of risk. For example, cyber attacks allow the perpetrator to maintain a great distance from the target—sometimes as far away as a different country or continent—and so to incur little or no physical risk. At the other end of the spectrum, suicide attacks pose the maximum risk, as the death of the perpetrator is all but assured. Midway on the spectrum of danger lie other attacks, such as deploying IEDs and participating in ambushes.

The different decision-making crossroads faced by the leaders and members of terrorist organizations can be grouped on two axes, which delineate the seniority of the decision maker in the organizational hierarchy and the degree of his involvement in the organization’s activity

FACTORS INFLUENCING THE DECISIONS MADE BY THE LEADERS AND MEMBERS OF TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS

The many decisions made by an organization’s leaders and members are influenced simultaneously by a complex system of factors, the majority of which fall into three categories.

Political and practical considerations.

Political and practical considerations. These take into account all of the terrorist organization’s root and instrumental goals and strategic interests. It is the leaders of an organization who must completely consider all of these factors. A terrorist attack initiated and perpetrated at a certain time or in a certain place—for example, with the intention to stop or impede a peace process—falls into this category.

Social-organizational considerations.

Social-organizational considerations. These are usually the result of socialization processes within an organization, and include a member’s desire to be affiliated with his peers, peer pressure, altruism, and the like.

7 Here a given member may decide to perpetrate a terrorist attack due to group pressure, or from a desire to be a role model or to be promoted in the organization’s hierarchy.

Personal considerations.

Personal considerations. These may emanate from an extreme desire for real revenge against some person or entity that the terrorist perceives as being responsible for an event that directly harmed him or one of his relatives, friends, or compatriots. Such considerations may emanate from feelings of loathing for the enemy, which have evolved in response to ongoing exposure to indoctrination and incitement. Or they may derive from the member’s complex psychological makeup (even if this makeup does not reach the level of psychological disorder).

8 Contrary to popular opinion, sociological and psychological research on terrorists in general, and on failed suicide attackers in particular, indicates that the majority of terrorists do not suffer from any psychological disorder.

9

Researchers into terrorism are divided as to which factors have the greatest influence on the decisions made by terrorists and their leaders. Their differences of opinion come to the fore when they are asked to answer the simple, but complex question: Why terrorism? What, if any, factors and variables explain the phenomenon of terrorism in its entirety? In a specific region? At a specific time? Or using a particular modus operandi? Differing viewpoints stem from differences in the disciplines from which terrorism researchers hail—psychology, sociology, political science, criminology, and philosophy, to name a few—and their differing tools of inquiry. Perhaps it is not possible to devise a sufficiently comprehensive explanation of terrorism based on any one discipline, as the multiple, varied decisions made by the leaders and members of terrorist organizations may at any time be influenced simultaneously by some or all of the political, social, and personal considerations cited above. How much influence any one of these considerations has on a given decision maker will vary from person to person, and from instance to instance. Nevertheless, the attempt to understand them is a key to understanding terrorism and its rationale—and hence to the success of counter-terrorism efforts.

It is important to note that a significant portion of these considerations may be influenced by pre-planned, sophisticated indoctrination, incitement and propaganda, which are used to shape the political awareness of even the least involved members of a terrorist organization, strengthen peer group commitments, amplify feelings of injustice and humiliation, and motivate members to wreak vengeance on the organization’s enemy.

The effectiveness of propaganda and incitement increases when these are grounded in religious justifications, interpretations and commandments. For example, instilling the belief that terrorism against “infidels” or “unbelievers” is a divine commandment is very powerful; the ability of such beliefs to motivate terrorists to attack cannot be underestimated.

Actually almost any significant decision made by a member or leader of a terrorist organization is influenced simultaneously by the three types of considerations cited above. At the same time, some decisions are naturally more likely to be influenced by one type of consideration than another. For example, the decision to establish a terrorist organization may be most influenced by the root goals that emanate from a given political reality (such as the desire for regime change, or the desire not to live under occupation). Conversely, the decision to passively support a terrorist organization may be influenced by the instrumental goals that emanate from a popular perception of political considerations (such as identification with a certain ethnic or national group that is party to a regional conflict). The decision to volunteer to perpetrate a terrorist attack, however, is most likely to be influenced by personal and social-organizational factors such as peer pressure or a desire for revenge. Understanding these varied considerations is crucial to exploring the rationale behind specific types of terrorist attack—including suicide attacks and unconventional attacks that use chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) weapons. This is the topic of

chapter 9.

The target or targets. This includes the type of target—e.g., civilian or military, carefully chosen or random—and its location, in enemy territory or elsewhere.

The target or targets. This includes the type of target—e.g., civilian or military, carefully chosen or random—and its location, in enemy territory or elsewhere. The target or targets. This includes the type of target—e.g., civilian or military, carefully chosen or random—and its location, in enemy territory or elsewhere.

The target or targets. This includes the type of target—e.g., civilian or military, carefully chosen or random—and its location, in enemy territory or elsewhere. The timing. Should the attack be conducted during the day or at night, at rush hour or during a lull in traffic, on a symbolic day such as Memorial Day or Independence Day or on a random weekday?

The timing. Should the attack be conducted during the day or at night, at rush hour or during a lull in traffic, on a symbolic day such as Memorial Day or Independence Day or on a random weekday? The message to be conveyed by the attack. Should the attack be accompanied by a frightening message that will intensify the dread and anxiety of the target population? Should it send a message of deterrence in retaliation for a counter-terrorism campaign?

The message to be conveyed by the attack. Should the attack be accompanied by a frightening message that will intensify the dread and anxiety of the target population? Should it send a message of deterrence in retaliation for a counter-terrorism campaign? The scope of the attack. Will it be a large-scale attack, killing and injuring many people? Or will it be a small-scale attack? Should the attack be one sporadic incident or part of an ongoing campaign of guerrilla warfare or terrorism?

The scope of the attack. Will it be a large-scale attack, killing and injuring many people? Or will it be a small-scale attack? Should the attack be one sporadic incident or part of an ongoing campaign of guerrilla warfare or terrorism? The type of attack. What methods will be used in the attack? Will it be a suicide attack, a hijacking, a bombing?

The type of attack. What methods will be used in the attack? Will it be a suicide attack, a hijacking, a bombing?

The internal community. That is, the terrorist organization’s population of origin, including its members and supporters, and the people the organization purports to represent.

The internal community. That is, the terrorist organization’s population of origin, including its members and supporters, and the people the organization purports to represent. The attacked community. That is, the opponent population or enemy state—an ethnic group, a religious or cultural minority, followers of a certain ideology, or a political group.

The attacked community. That is, the opponent population or enemy state—an ethnic group, a religious or cultural minority, followers of a certain ideology, or a political group. The international community. That is, world public opinion, especially that of liberal and politically engaged third-party citizens, who traditionally support the perceived “underdog.”

The international community. That is, world public opinion, especially that of liberal and politically engaged third-party citizens, who traditionally support the perceived “underdog.” International political developments ranging from conflicts to peace processes, and including specific events such as the eve of the signing of an agreement, the time preceding the implementation of a signed agreement, meetings between representatives of adversaries; the evolution of international (or local) crises and wars; counter-terrorism and military operations against the terrorist organization, which have a “boomerang effect,” i.e., that motivate a counter-attack3; summit meetings of heads of state; political assemblies.

International political developments ranging from conflicts to peace processes, and including specific events such as the eve of the signing of an agreement, the time preceding the implementation of a signed agreement, meetings between representatives of adversaries; the evolution of international (or local) crises and wars; counter-terrorism and military operations against the terrorist organization, which have a “boomerang effect,” i.e., that motivate a counter-attack3; summit meetings of heads of state; political assemblies. Memorial days, or the commemoration of meaningful events in the history of the terrorist organization, such as the day the organization was established, the anniversary of a significant attack carried out by the organization, the anniversary of the death of one of the organization’s leaders or prominent members, religious ceremonies and festivals.

Memorial days, or the commemoration of meaningful events in the history of the terrorist organization, such as the day the organization was established, the anniversary of a significant attack carried out by the organization, the anniversary of the death of one of the organization’s leaders or prominent members, religious ceremonies and festivals. Regional and international events that attract large crowds and receive extensive media coverage, such as the Olympic Games, the Boston Marathon, or the World Economic Forum at Davos.

Regional and international events that attract large crowds and receive extensive media coverage, such as the Olympic Games, the Boston Marathon, or the World Economic Forum at Davos. Pressure or demands from a sponsor state, such as that an attack be perpetrated in exchange for aid, or that an attack advance the sponsor’s interests and worldview—even if these contradict or discount the interests and goals of the terrorist organization itself.

Pressure or demands from a sponsor state, such as that an attack be perpetrated in exchange for aid, or that an attack advance the sponsor’s interests and worldview—even if these contradict or discount the interests and goals of the terrorist organization itself.

Pressure from the terrorist organization’s population of origin. Most terrorist organizations are receptive to the grievances, demands, and feelings of their “home” population. At times, an organization’s constituency may help to curtail its activities. At others, a constituency incited by hatred, anger, and a desire for revenge may spur an organization to action. It is important to note, also, that external bottom-up influences may not necessarily be based on concrete evidence of violent sentiments among the organization’s population of origin, but rather on the perception of the organization’s leadership, which may not necessarily reflect reality.

Pressure from the terrorist organization’s population of origin. Most terrorist organizations are receptive to the grievances, demands, and feelings of their “home” population. At times, an organization’s constituency may help to curtail its activities. At others, a constituency incited by hatred, anger, and a desire for revenge may spur an organization to action. It is important to note, also, that external bottom-up influences may not necessarily be based on concrete evidence of violent sentiments among the organization’s population of origin, but rather on the perception of the organization’s leadership, which may not necessarily reflect reality. Competition among rival terrorist organizations that claim to represent the same population. In such cases, the decision to launch a terrorist attack may be designed to demonstrate to the population of origin that a given organization is more determined and capable than its rivals.

Competition among rival terrorist organizations that claim to represent the same population. In such cases, the decision to launch a terrorist attack may be designed to demonstrate to the population of origin that a given organization is more determined and capable than its rivals. One-upmanship: that is, a response to a terrorist attack by a rival organization, which is meant to imitate, best, or “ride on” the success of the competitor.4

One-upmanship: that is, a response to a terrorist attack by a rival organization, which is meant to imitate, best, or “ride on” the success of the competitor.4 An attempt to raise the morale of the terrorist organization’s members.

An attempt to raise the morale of the terrorist organization’s members. An impetus from the organization’s spiritual leadership, be it ideological or religious in nature. Even in the absence of hierarchical compliance, an organization’s operative leadership may be guided and strongly influenced by its spiritual leadership, because of its inherent appreciation of the latter’s authority.

An impetus from the organization’s spiritual leadership, be it ideological or religious in nature. Even in the absence of hierarchical compliance, an organization’s operative leadership may be guided and strongly influenced by its spiritual leadership, because of its inherent appreciation of the latter’s authority. The simple fact of opportunity, created, for example, by the presence of a member of a terrorist organization who has particular skills or capabilities, or by the accessibility of a potential target.

The simple fact of opportunity, created, for example, by the presence of a member of a terrorist organization who has particular skills or capabilities, or by the accessibility of a potential target. Internal competition among an organization’s leaders, units, or members.

Internal competition among an organization’s leaders, units, or members. A desire to test the reliability and determination of a member whose peers suspect him of collaborating with an enemy state.

A desire to test the reliability and determination of a member whose peers suspect him of collaborating with an enemy state.

Political and practical considerations. These take into account all of the terrorist organization’s root and instrumental goals and strategic interests. It is the leaders of an organization who must completely consider all of these factors. A terrorist attack initiated and perpetrated at a certain time or in a certain place—for example, with the intention to stop or impede a peace process—falls into this category.

Political and practical considerations. These take into account all of the terrorist organization’s root and instrumental goals and strategic interests. It is the leaders of an organization who must completely consider all of these factors. A terrorist attack initiated and perpetrated at a certain time or in a certain place—for example, with the intention to stop or impede a peace process—falls into this category. Social-organizational considerations. These are usually the result of socialization processes within an organization, and include a member’s desire to be affiliated with his peers, peer pressure, altruism, and the like.7 Here a given member may decide to perpetrate a terrorist attack due to group pressure, or from a desire to be a role model or to be promoted in the organization’s hierarchy.

Social-organizational considerations. These are usually the result of socialization processes within an organization, and include a member’s desire to be affiliated with his peers, peer pressure, altruism, and the like.7 Here a given member may decide to perpetrate a terrorist attack due to group pressure, or from a desire to be a role model or to be promoted in the organization’s hierarchy. Personal considerations. These may emanate from an extreme desire for real revenge against some person or entity that the terrorist perceives as being responsible for an event that directly harmed him or one of his relatives, friends, or compatriots. Such considerations may emanate from feelings of loathing for the enemy, which have evolved in response to ongoing exposure to indoctrination and incitement. Or they may derive from the member’s complex psychological makeup (even if this makeup does not reach the level of psychological disorder).8 Contrary to popular opinion, sociological and psychological research on terrorists in general, and on failed suicide attackers in particular, indicates that the majority of terrorists do not suffer from any psychological disorder.9

Personal considerations. These may emanate from an extreme desire for real revenge against some person or entity that the terrorist perceives as being responsible for an event that directly harmed him or one of his relatives, friends, or compatriots. Such considerations may emanate from feelings of loathing for the enemy, which have evolved in response to ongoing exposure to indoctrination and incitement. Or they may derive from the member’s complex psychological makeup (even if this makeup does not reach the level of psychological disorder).8 Contrary to popular opinion, sociological and psychological research on terrorists in general, and on failed suicide attackers in particular, indicates that the majority of terrorists do not suffer from any psychological disorder.9