Mishnah Baba Batra 8:5 – The Transformation of the Firstborn Son from Family Leader to Family Member53

1 Introduction

Mishnah Baba Batra 8:5 states that biblical law requires a father to bequeath two inheritance portions to his firstborn son.54 That same mishnah also instructs how to get around the biblical requirement. The legal flexibility proposed enables one to gift to the firstborn a single share or to another son the double portion. This legal conception may be paralleled in ancient near eastern and (some strata of) Biblical law. In a separate article, I discuss this mishnah in light of its potential ancient legal parallels.55 In this essay, I investigate the effects of social context on the law. Based on both textual and archeological data, below I discuss the structure of the household in Biblical Israel as opposed to in tannaitic Palestine. The former was an extended family household which required a family leader or administrator; the latter was a nuclear family household which did not. The flexibility in ancient near eastern and (some) Biblical law reflects the importance that accompanied the firstborn’s leadership position within the family in those social contexts. At times, a son other than the biological firstborn was appointed to lead the family and preserve the estate upon the father’s death. The flexibility in m. Baba Batra 8:5, however, came to be for the opposite reason. The absence of a defined role for the firstborn within the household in the social context of tannaitic Palestine enabled the emergence of legal flexibility.56 We begin with an examination of the mishnaic text.

2 The Mishnah

While m. Baba Batra 8:5 declares that, as per deuteronomic law,57 the firstborn receives a double portion of inheritance, it also innovates a way around this law. The mishnah reads:58

- One who says, ‘Such-a-one, my firstborn son, shall not receive a double portion’ ... has said nothing, for he has laid down a condition contrary to what is written in the Torah.

- One who apportions [= gifts] his property (to his sons) by word of mouth, gave much to one and little to another or made the firstborn equal to them his words remain valid.

- But if he said that so it should be “by inheritance,” he has said nothing.

- If he wrote down, whether at the beginning or in the middle or at the end that thus it should be “as a gift,” his words remain valid.59

Section 1 states that one may not bequeath to the firstborn a single inheritance share (and, based on the greater context of our mishnah, implies that one may not bequeath to another son the double portion; see below). However, as explained in sections 2, 3 and 4, the very same outcome may be accomplished by gifting.60 Indeed, gifting enables the donor to increase or decrease the sons’ shares; and, as the Palestinian Talmud notes, even the firstborn’s double portion may be reassigned!61 It is explicit in the mishnah that one may gift to the firstborn a single share (“made the firstborn equal to them”) and implicit that one may gift the double portion to a non-firstborn son (“gave much to one and little to another”). In light of the inflexibility offered in section 1, the flexibility promoted in the mishnah’s subsequent paragraphs requires further exploration. Below I investigate the firstborn’s function - or lack thereof - within the household and the eventual emergence of the flexible approach in tannaitic law.

3 Household Structure and the Firstborn in Biblical Israel verses Tannaitic Palestine

A study of both textual and archeological evidence points to the conclusion that the structure of the household - and the role of the firstborn son within it - changed dramatically from the biblical period to the tannaitic period. Through a process likely protracted over the course of centuries,62 the Biblical period’s extended family with a ‘firstborn’ at its head (whether by lineage or appointment; see below) was replaced by the nuclear family of the tannaitic period,63 without an appointed or inherited head of household with obligations to the extended family.64

In his analysis of the Biblical term for household, bet av (literally, ‘house of the father’), Karel van der Toorn demonstrates that the textual and archeological evidence combined supports the notion that the bet av was an extended family unit. It included parents, children, spouses of sons and their offspring and possibly unmarried relatives and servants all living in close physical proximity 65 (even if not in the same house).66 At the head of the family was the father or the firstborn son.67 He was the extended family household’s leader and administrator.68 In fact, in the ancient near east the firstborn’s role often included caring for the widow and unmarried children in the household, ensuring the proper burial of the parents and performing cultic rituals after their death, functions likely prevalent in Biblical Israel as well69 and possibly warranting the firstborn’s receipt of extra inheritance. Due to the important function of the first born, flexibility developed regarding his appointment.70 A patriarch could either confirm his firstborn’s future post or designate someone other than his biological firstborn head of the family.

By the tannaitic period, the structure of the household had, for the most part, changed. The nuclear household was predominant71 and the firstborn son seemingly had no official role within it.72 Indeed, while tannaitic sources affirm that according to biblical law the firstborn automatically receives a double portion73 they do not indicate that the firstborn has any specific leadership function within the tannaitic family.

The predominance of the nuclear family by the tannaitic period is supported by both textual and archeological evidence.74 Nissan Rubin has suggested that a move away from the extended family towards the nuclear is reflected in the tannaitic laws of mourning.75 According to Rubin, the earliest layers of tannaitic literature inform us that mourning rites are to be observed even for members of the extended family; the later layers of tannaitic literature begin the process of shifting the mourning practices only to members of the immediate family.76 A similar development is suggested by archeological evidence for Jewish funerary customs in antiquity. Archeologists have noted that First Temple rock-cut tombs seem to have served large numbers of people - most likely extended families.77 Gabriel Barkay has even suggested the possibility that the remains of the family leader may have been centrally placed within the tomb!78 Second Temple period tombs, however, seem to have served only the immediate family.79

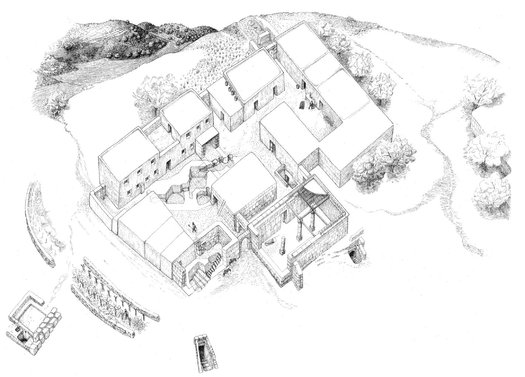

Tannaitic traditions about housing arrangements show the rabbis’ awareness of the concept of the nuclear family. M. Eruvin 6:7, for example, mentions “brothers who eat at their father’s table but sleep in their own houses.” This text refers to a father and sons who reside in adjoining houses with a common courtyard [see figure 1], “the most characteristic type of domestic architecture in Palestine.”80 Although the father and the sons reside in the same courtyard complex, according to this source,81 the residents must perform an act creating a shared domain, an eruv ḥatserot. The eruv ḥatserot is created by the residents jointly depositing foodstuffs. It enables the residents to carry on the Sabbath between the homes adjoined by the courtyard (see m. Eruvin chapters 6 and 7). The requirement indicates that the mishnah’s author views each son’s nuclear family unit as an individual household, independent from the father’s, at least under certain circumstances.82 Other tannaitic texts refer to partners and neighbors sharing a courtyard and not family members,83 demonstrating the degree to which courtyard housing is not representative of extended family housing, per se.84 Namely, independent nuclear families resided together in such complexes.

Fig. 1: The Jewish Village at Horvat ‘Ethri in the judaean Hills, Artist’s Reconstruction of the Main Buildings, ca. 70–135 CE (R. Graf, Courtesy of Boaz Zissu and Amir Ganor and the Israel Antiquities Authority).85

Archeological evidence for changes in landholding and settlement patterns also reflects a shift in the makeup of household structure. Shimon Dar’s study86 of settlement and landholding patterns in Samaria over the course of fourteen centuries contributes to our understanding of this development. Dar suggests that farmsteads dating to the Early Iron Age II–III (1000-586 BCE), similar to farmsteads found in both the Negev and Judea,87 represent “a characteristic model of settlement by kinships (extended families).”88 He observes that the farmhouses located on the grounds are large structures which likely housed twenty to thirty people.89 Furthermore, due to the lack of clearly marked boundaries for (what would have been) individual properties, Dar concludes that the data is representative of landholdings of members of the same beit av. Namely, at least in this period, multiple farmsteads were viewed as related to one another by those who worked and managed them.90

Dar also identifies field towers from the Hellenistic period which provide defined divisions for the cultivated areas. According to Shimon Applebaum, these point to a shift in the structure of the household by the Hellenistic period. Applebaum writes that the social agrarian importance of the evidence is that each tower represents a family unit and defines the precise area cultivated around a tower.91 The multiple towers, argues Applebaum, can “only be interpreted as representing units of nuclear families rather than the single unit of the extended beth av (kinship group).”92 Applebaum sees in the archeological evidence, therefore, a clear development from the extended family of the Iron Age to the nuclear family of the Hellenistic period. Similarly, the predominance of villages and cities along with the absence of large estates, manors and villas in Roman Galilee93 points to the following conclusion: by the Roman period the nuclear family was already predominant.

In summary, the textual and archeological evidence shows the predominance of the nuclear family by the tannaitic period. This data coupled with the absence of textual testimony about the firstborn’s role within the household is significant. It suggests that since there was no longer an extended family to administer, the firstborn’s role (or his replacement’s) as leader of the extended family had disappeared.94

4 Conclusions

With the collapse of the extended family unit and the eventual emergence of the nuclear family the role of the firstborn as family leader gradually disappeared. The changes in family organization enabled a flexible approach to the firstborn’s double portion allocation - possibly paralleled in ancient near eastern and (some strata of) biblical law - to emerge. The firstborn could be granted a single share or a son other than the firstborn could be given a double portion. Yet, the emergence of legal flexibility within the social context of the ancient near east and biblical Israel as opposed to tannaitic Palestine was for different reasons. While the legal flexibility in ancient near eastern and (some strata of) biblical law was due to the firstborn’s position as revered family leader, the flexibility present in tannaitic law was enabled by the firstborn’s social transformation into a mere family member.