Afterwords

The Use of Archaeology in Understanding Rabbinic Materials: An Archaeological Perspective

The title of this presentation is the same title I gave to a paper that was published in the Nahum Glatzer Festschrift in 1975.891 In thinking about the topic at that time I was most impressed with the kind of material that E. R. Goodenough had assembled in his programmatic work, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period.892 Goodenough taught at Brandeis after he retired from Yale, and it was in his classes that I came to love ancient Jewish art and archaeology. As a student of his at Brandeis before going on to Harvard where my focus was on a much broader chronological time span embracing more of the Biblical period, I was struck by the fact that not only was much of the material he cited undated, but much of it was unprovenanced also; and much of it had not been excavated in a stratigraphic manner. And yet Goodenough was ingenious enough to create an overall historical reconstruction for understanding that diverse corpus of material and postulated what he believed to be a Jewish mystical type of Judaism that was mirrored in the writings of Philo Judaeus and some of the rabbinic writings and reflected in the symbolic language of the art.893 The only problem was that over time his theories were strongly opposed and criticized, and while his corpus of material culture remains one of the most important resources for the study of ancient Judaism, there is still no unanimity in how to best understand its significance in the absence of well dated material.

Another influence on my thinking at that time was the sensitivity in Hebrew Bible circles to developing a theoretical framework for assessing the importance of great quantities of new material that were being uncovered in Israel that had direct relevance, so it seemed, on better understanding the biblical story. Indeed, up to this point a very positivist stance had been the hallmark of the American biblical archaeology movement led by Albright, Wright, and Glueck.894 While attempting to refine how one dealt with those materials in a positive way others, mainly in Europe, were beginning to question the relevance of using the entire Biblical literary corpus or just parts of it as it was presumably edited so late, either in the Persian or early post-exilic era or even later, in the Hellenistic period. By the late 1980s these scholars had been labeled the “minimalists” and the Americans “maximalists.” Today the battle continues and the new excavations in the City of David have exacerbated tensions between the Israeli maximalists such as Eilat Mazar and the Israeli revisionists, such as Israel Finkelstein, though Finkelstein calls himself a moderate.895 Was there a King David, and what was Jerusalem like before King Hezekiah? These are the most divisive questions now in Biblical studies, along with issues such as digging over the Green Line in hotly contested areas such as Silwan in the City of David, the settler movement sponsoring those digs and publications, the visitors’ center, etc.896

Samuel Krauss was the person who single-handedly created the discipline of “Talmudic archaeology” with his German publication of a book by that title in 1911–12.897 But despite his brilliance and detailed familiarity with rabbinic texts that dealt with material culture, his work was underappreciated and had only a small influence on the direction of the field of Jewish archaeology or the archaeology of early Judaism. Indeed, Albright’s ideal of studying texts and monuments together did not catch on in the later periods that are normally thought to be beyond the limits of Biblical archaeology. Only in recent decades has that ideal been applied to the discipline of New Testament archaeology, 898 and this conference is a testimony to the fact that the dialogue between Jewish material culture and contemporaneous literary sources is now part and parcel of the quest to reconstruct ancient Judaism. The disciplinary separation of archaeology in Israel, however, still remains a major problem and is symptomatic of the continuing desire in some circles to allow archaeology to go its own separate way. I remain committed to the idea that in order to more fully understand the world of ancient culture and Judaism in particular it is imperative to be immersed in the textual material including the visual and epigraphical sources that are chronologically relevant.899

Fig. 1: View of Temple Mount from the Air.

The main and most dramatic change that has affected this topic over the past generation is the vast amount of new material that has come to light. This process began most noticeably after 1967 when Israel took possession of territory that was identified with the story of Jewish life after the destruction of the Second Temple in the West Bank. The expansion of the IAA and the number of salvage excavations, and the beginning of new Israeli and foreign excavations, all led to an unprecedented collection of new data, much of which is just being published or becoming known to a wider audience. Indirectly, this new data has allowed the critical scholar to use the Goodenough corpus with a much greater degree of selectivity. Let me select some categories of data that have direct relevance for allowing the student and scholar of ancient Judaism to better understand aspects of rabbinic literature.

Jewish burial has provided a great deal of data that has illuminated rabbinic materials. Without a decent knowledge of Jewish burial practice in the Greco-Roman period, I cannot imagine how anyone could begin to understand the range of texts that deal with death and burial. We may begin with the important and key change from the Iron Age and Persian periods, the introduction of the coffin or individual burial receptacle in the Hellenistic period along with the ossuary in a slightly later period.

Although Jews continued to bury in subterranean chambers, the inauguration of the separate burial container may have given rise to the idea of individual identity in death, or else been the result of this change in perceptions of the individual.900 This contrasted strongly with the Iron Age custom of gathering the bones of the dead and placing them in pits or benches in underground tombs, reflected in the Biblical expressions “to sleep or be gathered to one’s ancestors”. Furthermore, in the Hellenistic and Roman periods the containers of the bodies or bones of the dead were often inscribed with the names of the deceased, suggesting that Hellenistic ideas were somehow attached to Jewish beliefs. And though the leading scholar on this subject believes that ossuaries reflect only Pharisaic ideas about life after death,901 the discovery of numerous ossuaries bearing the names of priests including the high priest Caiaphas, proves to me that we must be as careful both in reading the literary sources dealing with afterlife as we must in studying the artifacts themselves. Several scholars have also identified the custom of secondary burial as being at home in the early practice of the Jewish-Christian community of Palestine and reflected in the NT saying “let the dead bury the dead”. It is more fully represented in the statement attributed by some to Q: “But another said to him: Master permit me first to go and bury my father. But he said to him; Follow me, and leave the dead to bury their own dead” (Luke 9:59–60).902

Identifying a certain form of Jewish burial with a specific belief without the aid of an inscription, however, is very difficult if not impossible. Achieving a better understanding of the sources in the light of the realia, however, is something I think we all could agree on. Such a text would be m. Moed Qatan 1:5: “First they were buried in ditches. When the flesh wasted away, the bones were collected and placed in chests. On that day (the son) mourned, but the following day he was glad, because his forbears rested from judgment.”903 In light of recent public discussions about ossuaries and the Jesus tomb, it would seem totally appropriate for scholars of early Judaism who know rabbinics to become more conversant with the archaeology of Jewish burial in Second Temple times and in the Talmudic period.

In connection with the theme of Jewish burial I would like to draw your attention to the insightful article of Yonatan Adler904 who examines the phenomenon of ritual baths adjacent to tombs. The article is fully informed on material culture and Jewish tombs and miqva’ot as a starting point and goes on to examine the appropriate literary sources in the Bible, Qumran, and rabbinic sources. He concludes that such ritual baths were used by funeral participants who had contracted second-degree impurity through an intermediary source (i.e. physical contact with one who had contracted direct corpse impurity). Such an individual could be purged from that impurity on the very day in which it was incurred as opposed to a seven-day purification process. Adler offers that the large size of the ritual baths at the Tomb of the Kings in Jerusalem and at Bet She’arim may be explained as accommodating those leaving a funeral, and in these two cases, the individuals were upper class.

Another category is that of foodways. I think it is important for literary scholars of rabbinic materials to know that recent research of faunal specialists in collaboration with archaeologists has confirmed that at important Jewish sites and in areas that are exclusive to Jewish occupation, the absence of pig has been established beyond any shadow of a doubt and consequently interpreted to be proof of a Jewish presence or occupation. Stuart Miller has pointed out the text in b. Baba Metsia 24a that demonstrates the relevance of such research: “In a discussion of the kashrut of a slaughtered animal that has been found, it is decided that the area of the find is determinative (of its comestability). That is, if the animal was found in a place known for its Jewish settlement, such as the area between Sepphoris and Tiberias, it is permitted for consumption.” 905 As in modern research, then, where there is a correspondence between archaeological realia and the text we have a strong case for establishing the religious identity and ethnicity of a given population. This may not seem like such a great discovery or insight to some of you, but I can assure you that in late antiquity, in particular at urban sites with churches, synagogues, and pagan temples, it is not always easy to distinguish one group from the other when it comes to examining domestic or even industrial units. Careful examination of faunal remains thus could be most helpful in determining the makeup of small villages on the perimeter of major Jewish settlements or even of villages at a remove from such centers as in the Golan, and we indeed have identified Jewish sites from the Hellenistic and Roman periods that have produced non-kosher items such as hyrax, camel, catfish, and even small remains of pork. Whether such a site had a non-Jewish element or whether Jews consumed such items is an issue well worth pursuing in the future.

Two items that fall under the category of concern for ritual purity should also be mentioned in this context: chalk-stone vessels and ritual baths, miqva’ot. Each of these archaeological artifacts became a focus of interest only in the last decades, since the late 1980’s. There are several reasons for this. First, there was the doctoral thesis of Ronny Reich in 1990 on miqva’ot,906 and then the work of Yitzhak Magen on stone vessels, which first appeared in English 1994 as a catalogue to an exhibition of stone vessels at the Hecht Museum at Haifa University.907 These two publications led to a series of research trajectories that are today part and parcel of the archaeological discussions concerning ethnicity and even multiple uses for either artifact. The presence of several important sessions at this meeting proves my point that it is only the intersection of the disciplines of archaeology and higher critical use of rabbinic materials that will truly allow us to identify, understand, and explain many of the anomalies that confront scholars in the field.

Just a few words on stone vessels and then I will get on to ritual baths. Until recently stone vessels were dated to the late Second Temple period and regularly understood to be a sign of observance of purity laws for observant Jews. But we did not adequately understand them or even identify them properly when they were first presented by Magen and others. At Nevoraia (Nabratein), for example, when digging the site we had no idea what they were and our draughtsman drew all of them incorrectly. Only when we were about to go to press did we realize what they were and so we redrew all of them and had a special report written on them. And today, several scholars tell us that we must date some of them all the way down to the Byzantine period.908

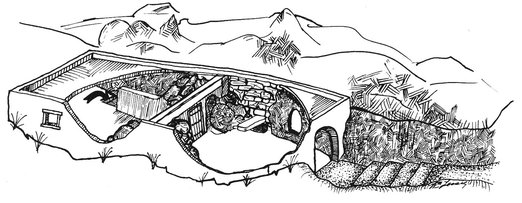

Let us turn now to the ritual baths. When Rabbi David Muntzberg - that is, the Rabbi Muntzberg who had positively identified Yadin’s miqva’ot at Masada - heard about our discovery of a ritual bath, he hired a driver and came up to Galilee to see for himself what we had uncovered. His first concern when he came to the site was that there was no out-drain for the water inside the miqveh but we soon concluded that the absence of such a drain was the case elsewhere and could not be a decisive factor in his considerations.909 In fact, at Sepphoris, in our corpus of thirty on the western summit, virtually every one lacks such a device, and hence we know that they were cleaned by hand, i.e., the older water removed in ceramic vessels. His second concern was that it did not look like a ritual bath or like the ones at Masada but more like an industrial installation, a kind of combination of cistern and part of an olive oil production site. But in viewing the evidence for a rather elaborate superstructure and covered entrance, not to mention a carved channel to direct rainwater into the cavity below, he began to accept the idea that the installation, was in fact for ritual bathing. One thing bothered all of us: along the stairs leading into the small chamber, on the western side and cut neatly into the bedrock, was a cavity large enough for a single person to comfortably sit and move albeit in a very confined space. We thought at first that it might be a place to store water jars used for removing water when it became necessary to replenish the pool. It was much too small to contain sufficient water for immersion and did not have the nice plastered surface necessary for it. In our continuing conversation Rabbi Muntzberg suggested that it could well be the place where long hair was washed and thoroughly rinsed before descending to fully immerse in the pure water below. This practice is known as ḥafifah and is known from both tannaitic and Talmudic sources (m. Miqva’ot 9:1—3 and b. Niddah 36b). This is an excellent case where the unusual character of the material remains led to a very special understanding of some rather obscure texts now made clearer through archaeology. I am certain many of you can provide other important examples.

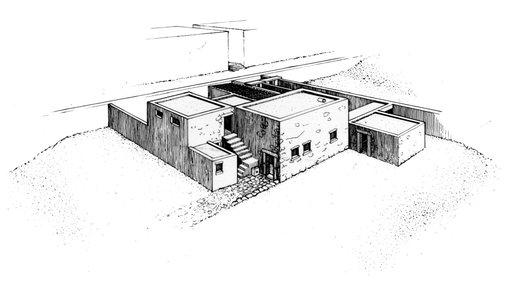

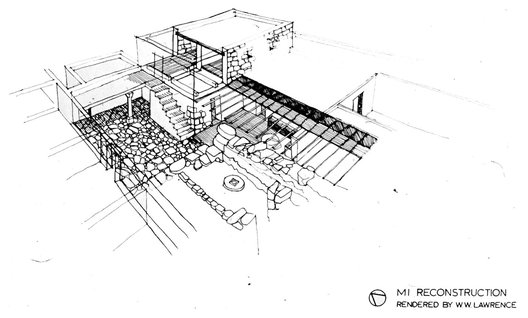

Fig. 3: Ritual Baths, Drawing, Photos, and Reconstructions.

Fig. 4: Ritual Baths, Drawing, Photos, and Reconstructions.

Fig. 6: Ritual Baths, Drawing, Photos, and Reconstructions.

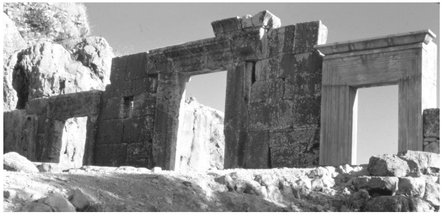

But as we also know archaeology can also cause us to wonder about literary references too, as is the case in regard to ancient synagogues. Let me give just a few examples. There is the common assumption that a synagogue is to be constructed on the highest point in town (t. Megillah 4:23: “One does not open the door of a synagogue except at the height of the city”). Two of the ancient synagogues I have excavated, Khirbet Shema‘ and Gush Halav, do not accord with this principle. The synagogue at Khirbet Shema’ is not only on the highest spot on the settlement, but in order to enter it from either of two major entrances, one has to descend a number of stairs.910 The synagogue at Gush Halav is built deep in the Wadi Gush Halav, hundreds of meters below the upper city and in the middle of the lower city, half of which is situated at an elevation well above the synagogue.911 Khirbet Shema‘ also presents other anomalies in respect to rabbinic law and practice as we might be inclined to understand it were it not for archaeology.

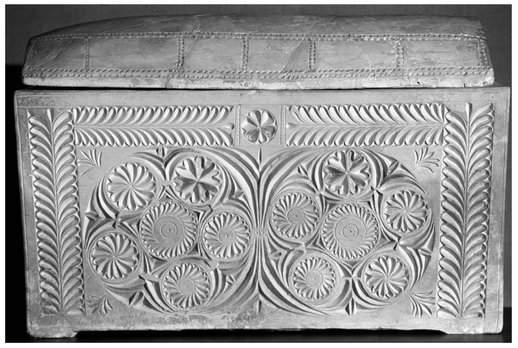

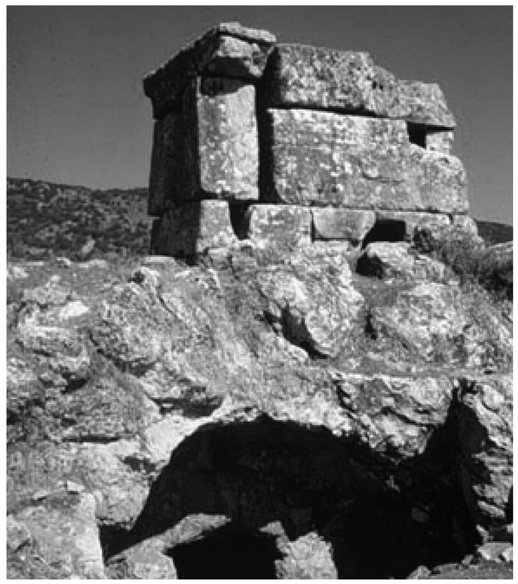

The most visible structure at Khirbet Shema‘ is a large monument attributed in medieval tradition to be the tomb of Shammai, hence the Arabic name tradition.

Underneath the mausoleum, which has two loculus graves cut into the upper portion of the monument, is a large subterranean tomb with loculi, arcosolia, and pit graves.912 While it was mostly robbed in antiquity, judging from its character and the character of the tombs on the eastern side of the settlement, it is contemporary with the main phases of the synagogue in the late Roman and early Byzantine periods. What is rather amazing, however, is that it is situated southwest of the main entrance of the synagogue, only tens of meters away, and appears to be on a major entrance path to the synagogue. Nearby is Tomb 31, which is closer still just north of the Mausoleum with an exposed entrance, the bedrock apparently too hard to finish the original carved entrance.913 I know no other such dramatic example of this from antiquity, and since we know the rules of corpse defilement, not to mention priestly defilement (Semaḥot ch. 4), its location is problematic, at least to the modern observer. There is also the issue of placing tombs beyond the city or town limits and downwind (m. Baba Batra 2:9; b. Ta‘anit 16a). Even under the floor of the synagogue we excavated declivities, several of which had human remains in them and likely served as tombs in an earlier period. While this may strike some as unusual and contrary to rules about purity, we have only to look across the Wadi Meiron to Meiron itself where we find a modern synagogue in an orthodox yeshiva built over an ancient burial ground and around and incorporating the venerated tomb of Bar Yoḥai.

All of these anomalies at Khirbet Shema‘ come from a settlement from the rabbinic period where we have a large ritual bath and every indication of a Jewish community that revered the Torah and worshipped in an elegant synagogue, which even had what appears to be a beit midrash, a “study house”, attached to it.914 The northern entryway was adorned with a beautiful menorah etched into its lintel.915

The final category I would like to examine briefly is gender. This is a field of study unto itself and rightly so but it has also become a rich area of study in archaeology and also in Talmudic archaeology. I will only allude to a variety of ways that it is relevant to our topic and illustrate it primarily through work done in connection with some of my work in Galilee. The first subcategory in this area concerns space and the traditional binary separation between public and private spheres, the shuq and the bayit. Mostly taken over from classical scholarship such a binary view of the male/female divide flies in the face of everything we know about private domiciles and the role of the courtyard as a place of coming and going of both sexes but also as a workplace for women and the extended family in food preparation and textile manufacturing. These latter subjects will comprise my final two areas of focus for this presentation. I have written about this in regard to the area in the lower sector of ancient Meiron where we have posited the presence of living quarters on the second storey of a large domestic complex that has a courtyard, a ritual bath of that complex, and even workshops in rooms on the ground floor.916 Given the layout of the typical simple and complex houses we have in Roman-period Palestine it is simply impossible to segregate gendered activities in any absolute way. We deduce this from archaeology and simple spatial considerations. The picture we get from rabbinic texts, however, is one that is superimposed from outside and unfortunately one that has given shape to the gendered narratives within that literature, which confine women to interior spaces and men to outside spaces and activities.

I offer two case studies to illustrate this matter of gender and space. First is the consideration of women and weaving. Textile manufacturing was one of the three top industries of ancient Palestine along with the production of olive oil and wine. In the classical literature weaving and loom technology play a central role in the assignment of gender (Herodotus, History 2.35), and for the topic in rabbinic literature I can refer to the pathbreaking work of Miriam Peskowitz, Spinning Fantasies: Rabbis, Gender, and History (1997).917 In pointing to the technical change from the older warp-weighted loom, its usage distinguished in the archaeological literature by the presence of loom weights, to the introduction in the mid-second century of the two-beam loom, she is able to chart not only how textiles were produced but “how their production was embedded in notions of gender, and how to conceptualize our interests in the category of everyday life.”918 One of the realities of textile production that relate to matters of space and domestic life is that the activities of production can and were carried out in domestic contexts as well as other places in the urban setting. Though Peskowitz has written as recently as 2004 that she believes the warp-weighted loom was replaced by the more versatile and efficient two-beam loom, having recently gone over the small finds plates from the domestic quarter at Sepphoris, we have abundant evidence that the “older” warp-weighted loom continued to be used in domestic contexts well into the Middle and Late Roman period at least at Sepphoris alongside the more efficient two-beam loom. That said, the technology shift certainly must have had a great impact on the industry, an industry served by men and women, boys and girls in a variety of settings.

Peskowitz points out that rabbinic literature from the talmudic, period sequesters women at their looms and repeatedly refers to them using the older, warp-weighted loom, whereas men are associated with both types of looms. One of the reasons for this is that the two-beam loom was more comfortable to use and easier to produce more highly woven cloth, which had a much higher value. The older loom was used with arms raised in a most uncomfortable posture while the newer loom could be used standing or sitting, a requisite for weaving the more intricate, tightly woven cloths. She proposes that m. Nega‛im 2:4, which uses the posture of a woman at work on a warp-weighted loom, is a purposeful way of denigrating women’s work by referencing the examination for leprosy to women’s under-arms, while standing, be-‘omdin, which is the work posture for such a loom. In m. Zavim 3.2 men are associated with both looms, both the older one at which they would work standing (be-‘omdin ) and the more modern one requiring the posture of sitting (be-yoshvin), and the impure man cannot transmit impurity to his work partner in the case of the two-beam loom. Once again she points to this as being favorable to the men at work.

A much more complicated scenario lies behind the situation in m. Kelim 2:1 and the parallel Tosefta passages, which discuss the purity implications for a menstruant at a loom and the intervention of a rabbinic authority, R. Ishmael, to settle the case.919 Given that there was not an absolute break in the technology but some overlap, attributing women to the older technology and holding them up to a higher purity standard, is just another way that women’s work was denigrated in the later textual world of the rabbis. And I would have to say that the archaeological reality of late antique Palestinian towns and villages as well as the urban built environment, simply does not allow a binary structure such as this to be a part of a judicious and careful history of culture that takes into account gender.

The final subcategory for gender I would like to address is baking. I am indebted to Carol Meyers for these last series of points. From earliest Biblical times one of the most labor intensive forms of work for women was making flour from wheat and then baking bread. The Hebrew Bible is full of positive references to women at work and women moved about freely in small village communities serving a wide variety of community needs. Women in Iron Age biblical society, as Carol Meyers has repeatedly pointed out, controlled an important variety of aspects of the household economy. Since high antiquity the manual grinding of grain to make flour was a task dominated by women. Experts conjecture that it took an hour of physical work at grinding to produce .8 kg of flour. It is estimated that a family of six would have required up to 3 kg of flour per day given the caloric requirements of the eastern Mediterranean diet, an investment of about 4 hours work in grinding. The technology for grinding remained more or less unchanged till the Hellenistic period and consisted of an upper and lower stone, the upper to grind on the lower quern, or flat stone, usually made of basalt.920 The first innovation was the adoption of the Olynthus mill taken from Greece, possibly originally brought from Asia, and it appears in the Roman period. The upper stone was moved over the lower stone with a wooden handle which made the work more efficient and much easier to do. About the same time the rotary mill was introduced and it has been found among the remains of Roman soldiers in the siege camps at Masada, and was more efficient still than the Olynthus mill but was not used by the Jewish population till the Byzantine period. Then came the donkey mill powered by draft animals, which according to Roman sources could in one day produce up to 873 liters of flour or about one hundred times what a single person could produce using a hand quern.

What has this to do with women at work at Talmudic archaeology? It has everything to do with it. As women were freed up from the “daily grind” of preparing flour, they had all sorts of new free time on their hands, which in the atmosphere I have described already was one in which a negative gender stereotype had come to predominate. Carol has collected some of the data from the rural site of Nabratein and has compared it to Sepphoris and as you can imagine the use of the donkey mill is much more common at the urban sites such as Sepphoris where three have been found on the western summit, though by the Byzantine period the rotary mill is most common in the small Jewish sites such as Khirbet Shema‘ or Nevoraia (Nabratein). At Sepphoris in the domestic area only two handstones have been found while we have fifteen different pieces of Olynthus mills documented among all the stone artifacts recovered.

The Mishnah and the Talmud are full of terms that refer to these implements of grinding but most of the rabbinic references do not offer any identity of the gender of the workers. Where the gender of the woman is specifically mentioned in using handstone grinders as in m. Oholot 8:3 ritual impurity is once again one of the main concerns. The conversion to mechanized and more efficient milling as in the donkey mill at Sepphoris meant that flour and ready-made bread could be purchased from new sources. This signified in some circles at least the diminution of women’s economic role in the home and hence meant less prestige and social standing. In smaller communities this could have meant that some women went over to textile work as they were freed from the long hours in flour production. But in the urban centers more leisure time was believed by men to be a major cause for female sexual dalliance: “idleness leads to unchastity” (m. Ketubot 5:5). Women, thus, could have been banned from the academies no doubt in part because they needed to be controlled with their newly found leisure time. As grinding came to a halt in the urban centers of learning such as Sepphoris, the elite, male authors of the rabbinic literature engaged in a kind of misogyny that did not apply to all of the rest of Galilean society, and its negative legacy lives on.

1 Conclusions

Something that may not seem so obvious but which underlies much that I have said is that archaeology can surely help with the general dating of some forms of rabbinic literature. I believe that much of Semaḥot, for example, can be reliably be assigned to the tannaitic or early rabbinic period since so much of it deals with the techniques of burial such as ossilegium that had a limited life span, and its technical vocabulary is not preserved in later strata of the literature. And we have also observed that archeology in general often provides a window to the text that is often inscrutable to the reader who is not attuned to material culture. Samuel Krauss could not have been attuned to material culture in the way one hundred years of excavation and publication allow it to be appreciated today. I hope that this conference goes a long way to overcoming the negative view that many Talmudic scholars have had in regard to archaeology and the material culture it brings to light.

In Boston some years ago at the 100th anniversary of the Archaeological Institute of America I appeared in a plenary panel with Jacob Neusner on this subject. Jack railed against archaeologists, saying in effect that the material we uncover and publish is inaccessible to most rabbinic scholars and we archaeologists simply have to do a better job of telling them, the literary scholars, what to do with the material we find. But Jack was assuming another binary that I believe we should finally once and for all discard, that is, the isolation of one kind of scholar from the other. I think it is clear to all of you, that we are all in this together and that to reliably and responsibly reconstruct the past we all have to work together. How can we make material culture a mainstay of the graduate curriculum, or even the undergraduate curriculum, when there is so much else to learn? This is a challenge the field of Jewish Studies must face and it is certainly worth our utmost attention.

The Use of Archaeology in Understanding Rabbinic Materials: A Talmudic Perspective921

1 Part I

“Talmudic realia” refers to the material culture of the people who lived in the period of the Mishnah and Talmud. Often called “late antiquity”, this period stretches from the late first century through the sixth or even the seventh centuries of the Common Era. “Talmudic realia” have been studied extensively since the second half of the nineteenth century, resulting in many excellent works, dissertations and articles. Near the turn of the twentieth century, Samuel Krauss elegantly summarized the state of the field in the early twentieth century in his encyclopedic three-volume work Talmudische Archäologie (1910–12).922 Parts of this work later appeared in a somewhat corrected two-volume Hebrew edition923 under the title Qadmoniot ha-Talmud.924 These volumes contain only a small part of the original material.925 This foundational work is now quite dated.926 Krauss did not sufficiently distinguish between earlier and later periods (i.e., between the Tannaitic period, late first-early third century and the Amoraic period, the early third to fifth centuries CE), nor between Sasanian Babylonia and Palestine. Similarly, proclivity for classical languages, Greek and Latin, led him at times to overlook Semitic or Iranian roots, and thus to overlook straightforward interpretations of the texts.927 Large numbers of manuscripts and critical editions are available to contemporary scholars that were simply unimaginable when Krauss wrote. It is now far easier to elucidate the text and to identify and eliminate errors among the variant readings. Most significantly, archaeological discoveries over the last century have transformed our understanding of everyday life in the Roman and Sasanian empires, the world in which the rabbis flourished.928

Since Krauss’ work, there has been no attempt to encompass all of Talmudic realia in a single work. The most comprehensive presentation is Catherine Hezser’s recent collection, The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Daily Life in Roman Palestine.929 As the field has developed, more specialized studies have been the norm. Flora and fauna were studied thoroughly from a philological perspective by a leading Semitic philologist of the late nineteenth century, Immanuel Löw of Szegedin.930 More recently, Yehuda Feliks focused on what he called “Talmudic agriculture,” and produced extensive and fundamental studies in the area.931 A. S. Hirschberg’s work on weaving and textiles in rabbinic literature (1924) is still unrivaled.932 The identification of pottery (and to a lesser extent of glassware) was expertly carried out by Joshua Brand (1953).933 More recently, David Adan-Bayewitz, a former student and a close colleague of mine, has researched this field, using more modern and sophisticated techniques. 934 In matters of boating and shipping, both in the Bible and the Talmud, much was done by Raphael Patai (1938, 1998)935 and more recently by the present author.936 Many archaeologists contributed to the solution of specific problems. These include Yigael Yadin, who dealt with locks, keys and metal tools937 and Yizhar Hirschfeld, who brought material culture together with literary evidence in the study of the late antique dwellings in the land of Israel.938 Uza Zevulun and Yael Olnick shed new light on a number of difficult halakhot relating to objects of daily life from the period of the Mishnah and the Talmud in a groundbreaking museum exhibition and catalog.939 Archaeologists have focused on ritual baths (miqvaot) and stone vessels,940 in order to understand the abundant recent discoveries.

The development of the study of “Talmudic realia” over the last century or so has been quite exceptional, and is important both to Talmudic studies and to the interpretation of material culture in late antiquity. Nonetheless, entire areas, particularly in the order of Toharot, “Pure things”, remain difficult, as the terminology for the study of material culture in this area is quite obscure. The primary scholarly tool for this research is still Saul Lieberman’s Tosefet Rishonim published in 1939.941 As a part of his larger project Lieberman published R. David Pardo’s (d. 1790) Ḥasdei David, a commentary to Tosefta Toharot.942 Taken together, Ḥasdei David, Lieberman’s comments to Pardo’s work and his own Tosefet Rishonim are essential for our understanding of this material.943

Within the Order of Toharot, Tractates Kelim (Vessels) and Ohalot (Tents) offer particular challenges. Traditional commentators as well as moderns have struggled to decipher the meanings of these texts. Methodologically, work in this field has to proceed in five stages.

- The first tool is the clarification of the text on the basis of manuscripts, quotations in the works of medieval halakhists (rishonim) and in parallels. The outstanding figure in this work was Saul Lieberman.944

One example of Lieberman’s method of dealing with textual problems will exemplify this approach. In t. Ohalot 16:5,945 we read:

What is virgin [soil]? That on which there are no marks and its soil is unturned earth. If he examined [by digging] and got to water, this is virgin soil.

If he examined and found potsherds, this is virgin soil ...”

The last phrase, “If he examined and found potsherds”, contradicts an explicit passage in Tosefta Shevi‘it 3: “Virgin land - this is whatever has never been tilled. Rabban Shimon ben Gamaliel said: Whatever does not have potsherds”946 The Rash (R. Samson of Sens) in his commentary on m. Ohalot 16:5 writes: “‘If he examined and found there potsherds, it is not virgin soil.’ That is, if he found there earthenware it is not virgin soil, because earthenware is made by human beings. And there are those who read, ‘And it is virgin soil’ etc.”

Regarding this problem, Lieberman wrote:947 “And it is clear that the version of ‘there are those who read,’ which is also the extant reading, is the original one, and the first reading is a correction based upon b. Niddah 8b quoted above.” He also notes that this is the reading of MS Vienna of the Tosefta. Lieberman then continues: ”But on the other hand, our reading is contradicts reality, and also contradicts the Tosefta itself at Shevi’it 3:15, p. 65 line 6 and Yerushalmi Niddah ... Because of these difficulties, R. Elijah of Vilna (in his glosses to Tosefta Ohalot, ch. 14) read: ‘This is not virgin land’, and likewise the author of Zer Zahav and Minhat Bikurim [by R. Shmuel Avigdor, Head of the Rabbinic Court in Karlin] ad loc., but he added, ‘And there are those who read, “It is virgin land”, for earthenware is also not plowed up’. Similarly, the author of Sidrei Toharot to Ohalot 16:4 (213b): ‘This is not virgin land.’ The various readings are discussed by the Rash, who concludes (ad loc.): The correct reading is like that which is before us: ‘It is not virgin land.’ Samuel Klein questions this conclusion in his book, Toldot Hakirat Erets Yisrael be-Sifrut ha-’Ivrit ha-kellalit (Jerusalem 1937), 138. Lieberman suggested the following solution: only regarding the environs of graves would the law be that the earth is considered as virgin soil if there is no impression in it and there is no overturned earth, even though one found potsherds there.948 This is because, since the soil is hard, this proves that it has not been dug up for a long time, just like if the diggers had reached the water. Later, however, he suggested another way of resolving the issue.949 First he shows that his earlier suggestion creates further difficulties, and that the language of the Tosefta comes out confused, since it should have read: “If he checked, even if he found there potsherds, it is virgin soil.” Lieberman then writes as follows:

It therefore seems to me that we have here a very small scribal error, and that it should have read:

(‘this is as at the beginning’). That is to say: if he came to soil in which there is no impression and its soil has not been overturned and he found there earthenware, he needs to examine further until he reaches real virgin soil. And in any event it is clear that this was the reading which was seen by Maimonides (Hilkhot Tum’at Met 9:6), as he writes there: ‘If he went down even a hundred cubits and found potsherds, this is like the beginning, and he must go down until he reaches virgin soil. If he reached water level this is virgin soil.’ And one can clearly see from his language that he copied according to the Tosefta passage at hand, and not according to the above-mentioned passage from Bavli Niddah.950 This correction is very small, and it enables us to justify our (corrected) reading, which is the more difficult one and thus that which seems more likely one on the basis the well-known rule lectio difficilior. In addition, with this correction the formulation is similar to an adjacent text, in t. Shevi’it 3:3 (y. 614 line

10): “... and they only said this for one who found three at the beginning” (

(‘this is as at the beginning’). That is to say: if he came to soil in which there is no impression and its soil has not been overturned and he found there earthenware, he needs to examine further until he reaches real virgin soil. And in any event it is clear that this was the reading which was seen by Maimonides (Hilkhot Tum’at Met 9:6), as he writes there: ‘If he went down even a hundred cubits and found potsherds, this is like the beginning, and he must go down until he reaches virgin soil. If he reached water level this is virgin soil.’ And one can clearly see from his language that he copied according to the Tosefta passage at hand, and not according to the above-mentioned passage from Bavli Niddah.950 This correction is very small, and it enables us to justify our (corrected) reading, which is the more difficult one and thus that which seems more likely one on the basis the well-known rule lectio difficilior. In addition, with this correction the formulation is similar to an adjacent text, in t. Shevi’it 3:3 (y. 614 line

10): “... and they only said this for one who found three at the beginning” ( –-– but it should read

–-– but it should read  , as cited by the Rash on Ohalot, ibid., end of ch. 3); and ibid., 1. 6, “He found two at the beginning (

, as cited by the Rash on Ohalot, ibid., end of ch. 3); and ibid., 1. 6, “He found two at the beginning ( )”; and ibid., 1. 7, etc.”951

)”; and ibid., 1. 7, etc.”951The methodological implications of this example are of some significance. In the first stage, Lieberman observes the contradictions among the sources. Secondly, he notes the halakhic and practical difficulties in the passage as it is. He then examines the variant readings in the printed texts, the manuscripts and among the medievals, in order to determine the variety of options available among those versions known to us from the sources. He states that the correct reading is the most difficult one, based upon a well-known rule of correcting texts, and explains the creation of the easy and coherent-seeming secondary reading. Lieberman then makes a minor correction, which resolves the problem and reconstructs the original text, which may be explained by the use of a similar style in other adjacent passages, which are clear and coherent from the halakhic viewpoint. In order to complete his task, he notes that this was the version used by Maimonides. Hence, he is not innovating a new reading, but merely discovering that which was known to the medieval tradents.952

- The second tool is philological. When dealing with technical terms, one needs to take note of the etymology of the words, which are often loan words from Aramaic, Latin, Greek, Persian, and even Coptic. These first two tools are inextricably bound together.953 The ground-breaking work of Krauss and of Lieberman is essential for this study. In t. Kelim, Baba Metsi‘a 2:4, p. 580, we read: “If he bought scales of hatchelled wool or

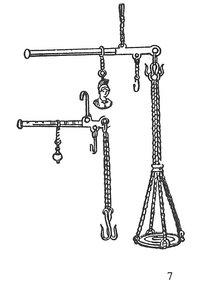

flax: if it had onqiyot but not onqal‘ot, onqal’ot but not onqiyot, it is impure. If the onqaliyot were removed, it is pure; when he connects them, it is a connection for impurity and for sprinkling ...” Generally speaking, scales have onqiyot – i.e., weights - on one side, and onqal’ot – that is, hooks upon which to hang the object being weighed - on the other side (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1: Roman Scales.

Fig.2: Roman Scales.

On the face of it, it is difficult to understand why the Tosefta drew a distinction between the weights and the hooks: if either of them is removed from the beam of the balance, it is impossible to use the scales in the normal manner. As a consequence, they would not be a functioning tool, and would not be able to become impure. Furthermore, why does the Tosefta mention only the onqal’ot in relation to being removed? Shouldn’t the same rule apply in the case that the onqiyot were removed? Thus, it should have said: “If its onqiyot or onqal’ot were removed, it is pure.” Perhaps one might argue that a pair of scales does not really require hooks, and that it may be possible to hang the object being weighed on the balance beam itself; or, perhaps, one might weigh objects which have their own handles for hanging; see Plate 6. Hence, as long as there are weights (onqiyot), even if there are no hooks (onqal’ot), it is still impure. If, however, the weights were also removed, it is pure, because the balance beam can no longer be used. But there remains a difficulty. Of what use is a scale without weights, and why should it be impure, as implied by the first phrase of our Tosefta passage?954

In m. Kelim 12:2 it states: “One who bought scales of hatchelled wool or flax, they are impure because of the onqaliyot (alternative reading: onqiyot ); and [scales] of householders, if they have onqaliyot they are impure.” J. N. Epstein wrote: “

... this is the reading in all the manuscripts and the medieval commentators. In the Tosefta (2:4) it is explicit: ‘If it has onqiyot but does not have onqaliyot,’ etc., which disagrees with this text. Maimonides and others interpreted

... this is the reading in all the manuscripts and the medieval commentators. In the Tosefta (2:4) it is explicit: ‘If it has onqiyot but does not have onqaliyot,’ etc., which disagrees with this text. Maimonides and others interpreted  as being the same as

as being the same as  , i.e., weights,

, i.e., weights,  . But it seems more likely to me that onqiyot are

. But it seems more likely to me that onqiyot are  ,

,  (Haken [hooks]), and that these are small hooks, as opposed to onqaliyot, which is a large hook,

(Haken [hooks]), and that these are small hooks, as opposed to onqaliyot, which is a large hook,  . In Roman scales there were two kinds of hooks (see Krauss).” (See Plate 7, and compare Plates 8 and 9).955 According to J. N. Epstein’s interpretation there must always be weights. According to the Mishnah, there must also be small hooks, onqiyot; according to the Tosefta, however, if the large hooks (onqaliyot), were

removed, the scale is pure, even though the weights (which are not mentioned in the Mishnah or the Tosefta at all, according to Epstein) are still attached.

. In Roman scales there were two kinds of hooks (see Krauss).” (See Plate 7, and compare Plates 8 and 9).955 According to J. N. Epstein’s interpretation there must always be weights. According to the Mishnah, there must also be small hooks, onqiyot; according to the Tosefta, however, if the large hooks (onqaliyot), were

removed, the scale is pure, even though the weights (which are not mentioned in the Mishnah or the Tosefta at all, according to Epstein) are still attached.We have not yet solved all the problems of the Tosefta. David Pardo writes (p. 86): “... And even if the balance beam is made of wood [the scale is impure], for the wood is only there to serve the metal, and the metal is the main thing - that is, the weights or the hooks. Hence, if the hooks were removed it is pure, and the same holds true if the weights were removed, and [the Tosefta] sufficed with mentioning only one of them. Not only is the balance beam pure, which is obvious, it being a simple wooden vessel, but the same holds true for the hooks alone or for the weights alone - they, too, are pure, for they are not suitable for work without the beam, and the scale would be considered like a broken vessel, even if a layman can put them back [together] ... But when they are connected, it is considered a connection both for the strictures of impurity and for the leniencies of sprinkling. This seems the correct interpretation of this Mishnah .”956 Although I have not fully explained his argument in every detail, it is clear that what is being discussed here is a type of scale called a “steelyard.”957

We thus find that the interpretation of the Mishnah and the Tosefta depends upon: (a) the textual readings:

or

or  ; (b) the etymologies: whether

; (b) the etymologies: whether  is derived from the Greek

is derived from the Greek  ,

,  , uncia “weight”, or from

, uncia “weight”, or from  = hook; (c) the literary approach, as in that of the author of Ḥasdei David, that “he mentioned only one of them”; (d) the interpretation of the legal issues underlying the discussion.958

= hook; (c) the literary approach, as in that of the author of Ḥasdei David, that “he mentioned only one of them”; (d) the interpretation of the legal issues underlying the discussion.958 - The third tool is the use of archaeological remains. When dealing with physical objects mentioned in Rabbinic sources, it is invaluable to locate archaeological remains from the same period, whether from the Land of Israel or from adjacent countries, -, which enable us to picture in clear and comprehensible fashion what the Sages were talking about in telegraphic form, without details, and often in passing.

- We also need, on occasion, to free ourselves from the conventions that cause us to imagine the reality of that time as being similar to that of today. Both medieval and modern commentators have fallen into this trap, seeking to interpret difficult passages in light of the reality known to them.959

- Above all else, the results of our research must correspond to the halakhic (or midrashic) context of the sources in question, just as our reconstructions must correspond to the material reality.960

These five tools must be used in concert with each other. As I emphasized above, text-critical and philological investigation are intertwined with one another. It is impossible to begin to know where to find that which is pertinent to our subject within the enormous treasure of archaeological findings, until we know what we are speaking of. Moreover, at times we find basic concepts within the world of the halakhah about which there is radical disagreement, so much so that it may seem as if there is no firm ground beneath our feet on which to base our conclusions. Hence, the five tools for approaching the sources given above must be used in concert, like “tongs made with tongs”. Only once we are able to see the full correspondence among the results of all these approaches may we offer a convincing interpretation. In other words, we need to combine together the textual, lexicographical - etymological, archaeological and halakhic approaches.

I attempted to follow these methodological guidelines in my small book devoted to the subject of ships in the Land of Israel at the time of the Sages, Nautica Talmudica,961 in which I combined a lexicographical-etymological approach with the clarification of the textual readings.962 I compared the results with archaeological findings from the same period, and tested the entirety in light of the halakhah.963 In this way I was able to verify my conclusions. I followed the same approach in a series of published articles and notes.964 These studies, along with the introduction to Nautica Talmudica, and the introduction to Material II (pp. 11–20) may exemplify the approach to be taken in clarifying difficult passages in Rabbinic literature relating to realia. At this point I wish to make a number of general observations:

- (1) Regarding etymologies of foreign words, one must remember that not all words in Rabbinic literature borrowed from foreign languages are to be found in the dictionaries of that language. I learned this from my esteemed teacher, R. Saul Lieberman,965 and have followed this principle in many papers.966 There are many reasons for this. One is the chance nature of the survival of literary sources. Another is that specific layers of the language, specifically that of the folk language, did not enter into the literary sources and therefore did not come down to us in the mainstream of the linguistic tradition. Hence, we need at times to reconstruct words, thereby simultaneously enriching the lexicon of that same foreign language with the addition of addenda lexicis.967

- (2) There are those cases in which the unique needs of the Jews, as dictated by the demands of Jewish law, led to unique innovations in the material and technological areas. See, for example, note 41 above, regarding lamps that were “closed” so as not to be susceptible to impurity. Similarly, the large number of stone vessels in the area of the Temple Mount derived from the fact that vessels of this kind are not subject to impurity.968

- (3) Occasionally novel interpretations of fundamental concepts in halakhah emerged from this study.969

- (4) There are some cases in which one may understand every word in a halakhic passage, yet it is nevertheless impossible to understand what is being spoken about until one finds a concrete example that illuminates the matter clearly.970

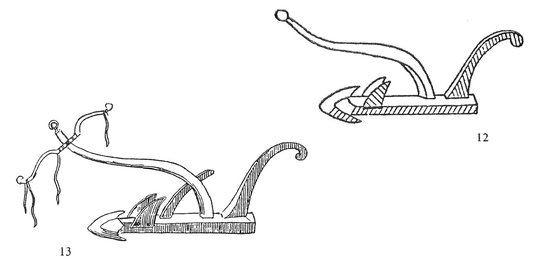

See, for example, t. Kelim, Baba Metsia’ 1:9 (Zuckermandel p. 579): “The

which has been broken through and its sting removed is pure. If there remained onqaliot on this side and that, it is impure.” Lieberman, Tosefet Rishonim, 3.35, wrote: “On the basis of the context, it would appear that this was a kind of decoration or instrument of war. See above, p. 468 1. 15 and the parallel in the Yerushalmi.” Lieberman is drawing our attention to t. Avodah Zarah 5:2 and its parallel in y. Avodah Zarah 3:2 (42b), where we find the phrase “The

which has been broken through and its sting removed is pure. If there remained onqaliot on this side and that, it is impure.” Lieberman, Tosefet Rishonim, 3.35, wrote: “On the basis of the context, it would appear that this was a kind of decoration or instrument of war. See above, p. 468 1. 15 and the parallel in the Yerushalmi.” Lieberman is drawing our attention to t. Avodah Zarah 5:2 and its parallel in y. Avodah Zarah 3:2 (42b), where we find the phrase “The  that is made as a kind of a dragon is forbidden, and if the dragon is hanging from it, he removes it and throws it away, and the remainder is permitted ...” This halakhah appears together with the laws concerning rings, and it is therefore reasonable to assume that it refers to some sort of decoration. Alternatively, given the mention of some sort of “point”, we may wish to conclude that it is an instrument of war, as per Lieberman’s second suggestion.971

that is made as a kind of a dragon is forbidden, and if the dragon is hanging from it, he removes it and throws it away, and the remainder is permitted ...” This halakhah appears together with the laws concerning rings, and it is therefore reasonable to assume that it refers to some sort of decoration. Alternatively, given the mention of some sort of “point”, we may wish to conclude that it is an instrument of war, as per Lieberman’s second suggestion.971Now, while the raḥush mentioned in Avodah Zarah clearly seems to be some kind of decoration in the form of a reptile or dragon, that discussed often in Kelim may be something else entirely, such as a metal utensil (as it is mentioned in a chapter that deals exclusively with metal tools) that has been broken and therefore became pure, and which has a point and two onqal’ot, or hooks. If we assume that the word raḥush is derived from or related to the word nahash “serpent”, then we may understand all the words in this brief passage, as well as all the details or parts of the raḥush, but we are nevertheless unable say with any confidence what it is.972

Now, we are speaking here of an artifact made of metal, which has a point and two hooks, and evidently shaped in the form of a snake. If it burst, that is, was broken, or if its point has been removed, it is no longer usable. If, however, there remained hooks on both sides, it may still be used, and therefore it is [potentially] impure. It seems to me that the text is discussing a belt buckle, made out of metal in the form of a snake, which has a point and two holders or hooks with which to hold the end of the belt. If it is burst, i.e., was broken, or the hook that goes into the hole of the belt and holds the end of the belt in place within the buckle is removed, then it is pure, for it is no longer usable in the normal way. However, the ends of the belt may still be held with the hooks of the buckle, so that one may still use it; hence, it is still subject to impurity973 (Cf. also m. Kelim 12:1: “a chain which has a locking device is impure; one made for tying up is pure). This is not, however, certain.

- (5) It is very important to note that the Sages, in both halakhic and aggadic sources, did not usually bother to provide a full description of the various tools, vessels, devices, etc., mentioned. Their audience understood what was being spoken about, and they only mentioned those things that were essential to the halakhic discussion.974

A number of specific scholarly tools are necessary in order for the type of scholarship I have described to move to the next stage of research. There is a need for a full bibliographical list of all those books and articles which have been written thus far pertaining to the realia of Rabbinic literature. Similarly, there is a need to assemble, from the vast treasure of archaeological findings, pictures of the tools, instruments, and objects relating to this area from the Hellenistic and Roman-Byzantine periods. The literary descriptions pertaining to these objects found in the Apocrypha and the Pseudepigraphic literature also needs to be gathered. There is need for monographs in a number of specific areas, such as furniture during the Rabbinic period, clothing, tableware,975 and so on. On the basis of these preliminary works, it will be possible to prepare an “Encyclopaedia of Talmudic Realia”, along the lines of Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities,976 or Daremberg and Saglio’s Dictionaire des Antiquités Grecques et Romaines.977 There is also need for detailed, illuminated commentaries on halakhic texts dealing with realia, such as Mishnah and Tosefta Kelim, certain chapters of Tractate Shabbat (such as Chapters 6, 7, 9 and 18), etc., analogous to the work done by Yehuda Feliks on Seder Zera‘im.978 My own studies have dealt with the reality and ambience of the Land of Israel at the time of the Sages.979 This is no more than a small fragment of a much broader picture. Nevertheless, as we devote ourselves to this area of study and delve into it more deeply, we will expand our field of vision until we see a more encompassing picture.

2 Part II980

A well-known jibe attributed to the world of traditional religious scholarship and directed against those involved in the academic study of Talmud has it that: “We (the traditionalist yeshiva world) want to know what [the Babylonian sages]Abbaye and Rava said, but they (the academics) want to know what they wore.” Now it is clear that anyone who devotes himself exclusively to the externals of Talmudic literature, such as historical background, philology and linguistic characteristics of Babylonian Aramaic, and so forth, will be missing the main point of learning. But, on the other hand, those who believe they are involved in real learning, but lack certain systematic disciplines, often miss the point themselves, and may even err when attempting to derive legal conclusions from a text. In terms of the jibe with which we opened, at times it is indeed important to know what Abbaye and Rava wore.

An example of this phenomenon appears in a medieval responsum, in which Rashi (Rabbi Solomon son of Isaac, d. 1105) - the preeminent commentator on the Talmud, is described thus:

Once I saw the master (Rashi) praying without a belt. I was puzzled and said: How is it that he is praying without his loins girdled? Surely they said in Tractate Berakhot (24b), that one may not pray without a belt, and the reason is that one’s heart should not behold the nakedness. And he (Rashi) replied: It seems to me that in those times the sages did not wear trousers, but merely long cloaks that went down close to their ankles.981 And all their clothes were closed front and back, left and right. Therefore they stated that one may not pray without a belt, for they had nothing to separate the heart from the nakedness other than the belt. (And indeed it seems likely that they had no trousers, for in Tractate Shabbat ... [120a] we have learned in a Mishnah what one saves from a fire [on the Sabbath], and eighteen items of clothing that a person may save on Shabbat are enumerated there ... but trousers are not mentioned.)982 But we do wear trousers,983 and even without a belt there is a clear separation between the heart and the nakedness, and therefore we may pray without a belt. 984

We see then that Rashi’s views as to Talmudic costume led him to rule halakhically on a certain issue, or at any rate to justify an existing custom.985 He probably visualized them wearing something akin to the contemporary garb. 986 Actually his explanation is based on a conjecture, and borne out only tentatively by oblique Talmudic evidence.

In fact, this text more complex than it first appears. For while indeed it is true that the Bavli does apparently not list trousers among its eighteen garments and reads  , (which Rashi explains as

, (which Rashi explains as  , probably meaning faissole, straps around the legs), 987 the Yerushalmi (Shabbat, 15d) reads:

, probably meaning faissole, straps around the legs), 987 the Yerushalmi (Shabbat, 15d) reads:  .988

.988  probably corresponds with the Latin braccae (in Greek: bra/kai “trousers, pantaloons”), 989 an article of attire well-attested in Roman times [Figs. 18 and 19]. It is true that they were less commonly worn by Romans than by the Northern nations, such as the Celts - indeed the word is of Celtic origin990 – or Asians, such as the Persians. However, in the second century CE they appear to have been worn in Rome as well (though later forbidden by the emperor Honorius in 397 CE).991

probably corresponds with the Latin braccae (in Greek: bra/kai “trousers, pantaloons”), 989 an article of attire well-attested in Roman times [Figs. 18 and 19]. It is true that they were less commonly worn by Romans than by the Northern nations, such as the Celts - indeed the word is of Celtic origin990 – or Asians, such as the Persians. However, in the second century CE they appear to have been worn in Rome as well (though later forbidden by the emperor Honorius in 397 CE).991

Now the attestation of the word in the Yerushalmi, and indeed elsewhere in Palestinian rabbinic literature,992 makes it clear that trousers were known of, and worn, in Talmudic Palestine. Furthermore,  “trousers”, are mentioned in rabbinic literature (e.g. m. Kelim 27:2, etc.). This strongly calls into doubt Rashi’s supposition, and makes his reasoning suspect. That Rashi was ruling in accordance with the Bavli and not the Yerushalmi - with which he may not have been acquainted993 - is a specious argument, since he explicitly based his ruling on an assumption as to real-life practices in Talmudic times, and the assumption has been shown to be questionable. One may, of course, choose to separate the various elements in this responsum, accepting the sevara (speculative reasoning), that “the heart may not see the privy parts” while rejecting the supposition that rabbis did not wear trousers and the proof for this from the Bavli. And in that case, the Talmudic directives in b. Berakhot 24b would be addressed to people wearing loose cloaks, but not to people wearing trousers. Be this as it may, what remains significant is that Rashi (or his disciples) apparently regarded the issue of whether the Tannaim wore trousers or not as meaningful to his argument, and hence consequential to his own style of prayer, and possibly to ours, too, for that matter. Thus, at times, knowledge of everyday life in Talmudic times can play a significant role in the understanding of a Talmudic text, and even in the subsequent process of halakhic ruling.994

“trousers”, are mentioned in rabbinic literature (e.g. m. Kelim 27:2, etc.). This strongly calls into doubt Rashi’s supposition, and makes his reasoning suspect. That Rashi was ruling in accordance with the Bavli and not the Yerushalmi - with which he may not have been acquainted993 - is a specious argument, since he explicitly based his ruling on an assumption as to real-life practices in Talmudic times, and the assumption has been shown to be questionable. One may, of course, choose to separate the various elements in this responsum, accepting the sevara (speculative reasoning), that “the heart may not see the privy parts” while rejecting the supposition that rabbis did not wear trousers and the proof for this from the Bavli. And in that case, the Talmudic directives in b. Berakhot 24b would be addressed to people wearing loose cloaks, but not to people wearing trousers. Be this as it may, what remains significant is that Rashi (or his disciples) apparently regarded the issue of whether the Tannaim wore trousers or not as meaningful to his argument, and hence consequential to his own style of prayer, and possibly to ours, too, for that matter. Thus, at times, knowledge of everyday life in Talmudic times can play a significant role in the understanding of a Talmudic text, and even in the subsequent process of halakhic ruling.994

I will conclude with a second example, also related to clothing. We begin with that which we find in m. Niddah 8:1:

A woman who has seen a bloodstain on her body adjacent to her genital area is (ritually) unclean; (if the bloodstain is) not adjacent to her genital area, she is clean ... (If) she has seen it on her garment  : below the belt

: below the belt  she is unclean, above the belt she is clean. (If) she has seen it on the sleeve of her garment: if the sleeve reaches below the line of her genital area, she is unclean; it it does not, she is clean. (If) she had been taking it off and putting it on during the night, anywhere she finds a bloodstain on it renders her unclean, since it returns (

she is unclean, above the belt she is clean. (If) she has seen it on the sleeve of her garment: if the sleeve reaches below the line of her genital area, she is unclean; it it does not, she is clean. (If) she had been taking it off and putting it on during the night, anywhere she finds a bloodstain on it renders her unclean, since it returns ( ); and the same applies to a pallium (

); and the same applies to a pallium ( ).

).

R. Ovadia Bertinoro (d. c. 1515) explained: “‘since it returns ( )᾽ –sometimes the top of the garment twists down to the genital area; ‘a pallion᾽ (his text is

)᾽ –sometimes the top of the garment twists down to the genital area; ‘a pallion᾽ (his text is  ) – a mitpaḥat

) – a mitpaḥat  with which she covers herself ...“ Tiferet Yisrael, n. 8, also explained: ”a mitpaḥat with which she covered her head, specifically without tying it, so that it was possible that it would twist towards her genital area.“ They both followed in the footsteps of the author of the Arukh, who defined the word

with which she covers herself ...“ Tiferet Yisrael, n. 8, also explained: ”a mitpaḥat with which she covered her head, specifically without tying it, so that it was possible that it would twist towards her genital area.“ They both followed in the footsteps of the author of the Arukh, who defined the word  in this Mishnah as “a mitpaḥat with which she covers herself.” Kohut has already pointed out995 that the Arukh is here following the Geonic author of a commentary on Teharot, who explains that the word

in this Mishnah as “a mitpaḥat with which she covers herself.” Kohut has already pointed out995 that the Arukh is here following the Geonic author of a commentary on Teharot, who explains that the word  found in m. Kelim 29:1996 and m. Niddah 8:1997 is derived from Greek and means mitpaḥat (see the editor’s note there, p. 114, n. 8, who determines that the author was referring to πιλίον, pileum, a felt hat).998 Rashi

(b. Niddah 57b) wrote:

found in m. Kelim 29:1996 and m. Niddah 8:1997 is derived from Greek and means mitpaḥat (see the editor’s note there, p. 114, n. 8, who determines that the author was referring to πιλίον, pileum, a felt hat).998 Rashi

(b. Niddah 57b) wrote:  – a ma᾽aforet

– a ma᾽aforet  with which she covers herself, an iril in ‘the foreign tongue’ (Old French).” Since this iril is apparently a headscarf,999 we may infer that Rashi too follows the Geonic approach.1000

with which she covers herself, an iril in ‘the foreign tongue’ (Old French).” Since this iril is apparently a headscarf,999 we may infer that Rashi too follows the Geonic approach.1000

The Geonic interpretation is difficult (as is Maimonides’), however, since it already says explicitly in m. Niddah 8:1 that: “(If) she has seen it on her garment ... above the belt she is clean”, and there is no place further above the belt than the scarf around her head! To say that the garment is so long that part of it reaches her genital area and that she is therefore unclean (like the rule for a bloodstain found on a sleeve of such length), would be a forced reading. Rather, we must conclude that all of the garment could reach that area, and, as the Mishnah says, “it returns” from place to place. Clearly, then, this commentator conflated the pilium- -πιλίον m. Kelim with the pallium-

-πιλίον m. Kelim with the pallium-  -παλλίον (‘mantel’) of Nidda, as Epstein already observed.1001 In the Aruch Completum (ibid), we read that R. Binyamin Mustafiya came to the same conclusion. 1002

-παλλίον (‘mantel’) of Nidda, as Epstein already observed.1001 In the Aruch Completum (ibid), we read that R. Binyamin Mustafiya came to the same conclusion. 1002

Indeed, one of the features of the pallium was its versatility: it could be worn in many ways and styles, at times in direct contact with the skin, without an undergarment beneath it, though more often as an outer garment. In the words of A. Rich:1003

A garment of this nature might be adjusted upon a person in various ways according as the fancy of the wearer or the state of the atmosphere suggested; and, as each arrangement presented a different model in the set and character of its folds, the Greeks [and the same was true for the Romans] made use of a distinct term to characterize the particular manner in which it was put on, or the appearance it presented when worn.

Fig. 3: An Example of a Roman Fibula.

Later, he summarized the major styles:

: meaning literally that which is thrown on or over ... when the center of one of its sides was merely put on to the back of the neck and fastened round the throat, or on one shoulder, by a brooch (fibula), so that all the four corners hung downwards ... [Fig. 3].

: meaning literally that which is thrown on or over ... when the center of one of its sides was merely put on to the back of the neck and fastened round the throat, or on one shoulder, by a brooch (fibula), so that all the four corners hung downwards ... [Fig. 3]. : meaning ... that which is thrown up ... i.e. when the part which hangs down on the right side ... was taken up, and cast over the left shoulder ... When thus worn, the brooch was not used; and the blanket, instead of being placed on the back, at the middle of its width, was drawn longer over the right side to allow sufficient length for casting on to the opposite shoulder.

: meaning ... that which is thrown up ... i.e. when the part which hangs down on the right side ... was taken up, and cast over the left shoulder ... When thus worn, the brooch was not used; and the blanket, instead of being placed on the back, at the middle of its width, was drawn longer over the right side to allow sufficient length for casting on to the opposite shoulder. : meaning ... that which is thrown round one ... so adjusted as completely to envelope the wearer all round from head to foot ... Women also wore the pallium ... as well as men, and adjusted it upon their persons with the same varieties that have already been described, as evinced by numerous works of art both in sculpture and in painting.

: meaning ... that which is thrown round one ... so adjusted as completely to envelope the wearer all round from head to foot ... Women also wore the pallium ... as well as men, and adjusted it upon their persons with the same varieties that have already been described, as evinced by numerous works of art both in sculpture and in painting.

Rich also cites evidence from a painting in Pompeii (from the mishnaic period) in which two women wear pallia (the plural form), each in a different manner. 1004 Thus we can conclude that the pallium 1005 is a garment which is wrapped around the majority of the body; it is sometimes worn on its own directly over the skin; and while it can be worn in different styles, it is never fastened tightly, moving easily back and forth over the body. Therefore, since most of it can come into contact with most parts of the body, it is a perfect example of a garment that “returns” from place to place, and so the Mishnah rules that “anywhere she finds a bloodstain on it renders her unclean.”1006 We see, then, that the confusion between pallium and pilium, which may look identical in the Hebrew transcription, brought about an unlikely interpretation of the Mishnah, which found its way into the law books, causing some consternation among poskim. However, familiarity with the nature of Talmudic clothing - in this case - clarified the whole issue.

3 Conclusion

The study of “Talmudic realia” is today an integral part of the study of Rabbinic literature with in the academic setting. This interest in the material culture that informs Rabbinic texts has its roots in the medieval period, but in fact is a product of the Wissenschaft des Judentums, and its adoption of the methods of scholarship practiced in the study of classical literatures and cultures. This article aims to provide a kind of “readers guide” to modern academic writing on this subject, with particular emphasis upon earlier, now often forgotten, scholarship. Through a series of poignant examples and methodological discussions, I have shown how one may bridge the gulf between texts and archaeology, particularly focusing upon the Land of Israel within its Roman matrix, where archaeological and literary sources are abundant and diverse, in the hopes of better understanding the world in which Rabbinic literature was written and formulated.