Mishnah Baba Metsia 7:7 and the Relationship of Mishnaic Hebrew to Northern Biblical Hebrew

Did Mishnaic Hebrew develop out of the spoken Hebrew current in the Galilee in the Biblical period, as some scholars have posited?13 For such a development to have taken place, there must have been a continuity of Jewish settlement in the Galilee from Iron II to the Greco-Roman period. But much of the scholarship on this question focuses on linguistic similarities, without engaging the evidence from material culture which would demonstrate such settlement continuity. The present paper uses the archaeological data bearing on settlement continuity to investigate the linguistic question of the origins of Mishnaic Hebrew. In turn, it uses the linguistic data to shed light on the development of the Jewish presence in the Galilee in the Greco-Roman period. This essay focuses upon Mishnah Baba Metsia 7:7, thorough which the issues to be discussed will be exemplified. This text reads as follows:

One who hires workers to work in his fruits of the fourth year [which must be either redeemed or eaten in Jerusalem], these workers may not eat [these fruits].

If [at the time of hiring,] he did not inform them [that these were fourth year fruits], then he must redeem [the fruits] and allow them [i.e., the workers] to eat.

If his fig-bundles were separated or his wine-barrels were opened [and he hires workers to re-bundle the figs or re-close the wine-barrels], then these workers may not eat [the bundles or barrels because they are obligated in tithes].

But if [at the time of hiring,] he did not inform them, then he must tithe [the bundles or barrels] and allow them [i.e., the workers] to eat.

1 Linguistic Comparisons: Mishnaic and Biblical Hebrew

Mishnah Baba Metsia 7:7, which aims to avoid giving agricultural workers false impressions about eating rights, illustrates two linguistic features which distinguish Mishnaic Hebrew from Biblical Hebrew. These are: (a) the use of  ’elu instead of

’elu instead of  ’eleh; (b) the

’eleh; (b) the  nitpa‛el form, new in Mishnaic Hebrew, and its use in a passive sense. It also contains the root

nitpa‛el form, new in Mishnaic Hebrew, and its use in a passive sense. It also contains the root  pa’al. Here used as a noun alongside the verb

pa’al. Here used as a noun alongside the verb  la‛asot, this root is frequently used in Mishnaic Hebrew instead of

la‛asot, this root is frequently used in Mishnaic Hebrew instead of  ‛asah as the standard verb for “to work, to do.” These three features are among twelve distinctive features of Mishnaic Hebrew that Gary Rendsburg noted in a 1992 article.14 Developing a suggestion made by Chaim Rabin, he argued that these features could best be explained as resulting from the influence of the northern dialect of Biblical Hebrew.15 The northern dialect of Biblical Hebrew (also known as Israelian Hebrew) is attested in Biblical and epigraphic texts deriving from the kingdom of Israel, as opposed to Judah. The twelve features Rendsburg noted are shared by Mishnaic and northern Biblical Hebrew.

‛asah as the standard verb for “to work, to do.” These three features are among twelve distinctive features of Mishnaic Hebrew that Gary Rendsburg noted in a 1992 article.14 Developing a suggestion made by Chaim Rabin, he argued that these features could best be explained as resulting from the influence of the northern dialect of Biblical Hebrew.15 The northern dialect of Biblical Hebrew (also known as Israelian Hebrew) is attested in Biblical and epigraphic texts deriving from the kingdom of Israel, as opposed to Judah. The twelve features Rendsburg noted are shared by Mishnaic and northern Biblical Hebrew.

Rendsburg acknowledged that the attestations in northern Biblical Hebrew of some of the twelve points noted can be debated. Nevertheless, there are clearly certain similarities between northern Biblical Hebrew and Mishnaic Hebrew, as well as similarities between Phoenician and both these dialects of Hebrew.16 These features can be divided into two groups. The first group consists of features attested only in Mishnaic and northern Biblical Hebrew, and not in Phoenician. These include lexical elements such as the root  na’am,

syntactic features such as

na’am,

syntactic features such as  hayah followed by a participle, as well as morphological features.17

hayah followed by a participle, as well as morphological features.17

The second group, which is both larger and more relevant to the present discussion, consists of features attested in Mishnaic Hebrew, northern Biblical Hebrew, and Phoenician.

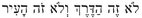

| Mishnaic Hebrew | Northern Biblical Hebrew | Phoenician |

|---|---|---|

Relative pronoun  |

In Pre-exilic Biblical Hebrew, occurs only in Northern contexts: | Standard Phoenician: |

|

|

|

| (Judges 6:17, in the story of Gideon) | ||

| ||

| (2 Kings 6:11, in the stories of Elisha) | ||

| Feminine Singular |  |

Phoenician:  and and  |

Demonstrative Pronoun   |

(2 Kings 6:19, in the stories of Elisha) | |

| ||

| (Hosea 7:16)18 | ||

| “Double Plural” Construction |  |

Frequently found in Phoenician |

|

| |

| (Judges 5:6, 10, in the Song of Deborah) | ||

19 | ||

| (Psalm 29, thought to be a northern Psalm) |

| Mishnaic Hebrew | Northern Biblical Hebrew | Phoenician |

|---|---|---|

Root  |

|

Standard verb for “to do” in Phoenician |

|

(Hosea 7:1) | |

| ||

| (Deuteronomy 32:27) | ||

Plural Construct  |

|

Standard Phoenician construct |

|

(Deuteronomy 32:7)20 |

To explain the origins of Mishnaic Hebrew, Rendsburg focuses on the similarities between northern Biblical Hebrew and Mishnaic Hebrew, rather than on the similarities to Phoenician. He argues that Mishnaic Hebrew is the dialectical continuation of northern Biblical Hebrew. In contrast, he sees the similarities to Phoenician as resulting from dialect geography. In this paper, I present evidence from historical demographics suggesting that Phoenician may have influenced Mishnaic Hebrew.

It is eminently reasonable to posit a Galilean origin for Mishnaic Hebrew, given the Galilean origin of the Mishnah and other early rabbinic texts. Rendsburg connects this to the hypothesis of continuity of Israelite settlement in the Galilee from the Iron II period (the tenth to eighth centuries) down to the early Rabbinic period. This hypothesis was supported by Hayim Tadmor, Sara Japhet, and other notable scholars.21 They held that populations speaking Israelian Hebrew survived in the Galilee and preserved their language, from Biblical times to Mishnaic times.

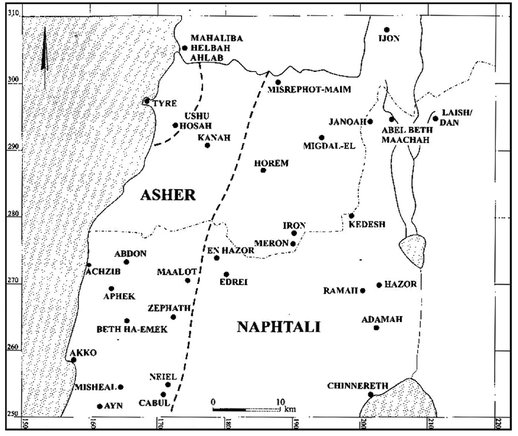

2 Archeological Evidence: Israelite Settlement in Iron Age Upper Galilee

This argument is called into question, however, by several recent studies of the historical geography of the Galilee. These are based on the archeological and textual evidence for the campaigns of Tiglath-Pileser III, king of Assyria, to Syro-Palestine in 733–732 BCE. These campaigns left a profound mark on settlement patterns in the Galilee, and these studies suggest that the degree of settlement continuity may be less than previously suspected. To understand the effects of these campaigns on Israelite settlement continuity from the Iron Age to the Greco-Roman Period, it is necessary to consider the broader historical context of Israelite settlement in the Galilee in the early Biblical period. Topographical features force us to divide any consideration of the Galilee in this period into the Upper Galilee, north of the Bet Ha-Kerem valley, and the Lower Galilee to its south. In the Upper Galilee, there is no clear archeological marker indicating the beginning of Israelite settlement in the Iron Age. In this region, there is little distinction between the pottery of the Iron Age and the pottery of the earlier periods, and the lack of a clear ethnic marker leads to the understanding that the Israelite tribes in this region “originated in indigenous elements.”22 Furthermore, the textual evidence in Judges suggests that Israelite settlement in the western part of Upper Galilee was limited (Judges 1:31–33). Only in the eastern part of the Upper Galilee, around Hazor, do we have clear textual evidence for Israelite occupation, in the stories of Deborah, in Joshua 10, and in the Solomonic district list in 1 Kings 4. The archeological record at Hazor also points to Israelite settlement in this period.

Because the area around Hazor was on the major north-south trade route, Israelite settlement in this area was completely uprooted in the Assyrian campaign of 733–732. The Biblical passages which describe the Assyrian conquest are very explicit in this regard: “In the days of Pekah king of Israel, Tiglath Pileser King of Assyria came and he took Iyyon and Abel-beth-maacah and Yanoah and Kedesh, and Hazor and Gilead and the Galilee, all the land of Naphtali, and he exiled them to Assyria” (2 Kings 15:29). Four of the five towns mentioned in this verse are located in the eastern Upper Galilee, along the main Megiddo-Beqa’ Valley highway, the most important north-south road in northern Israel.23 Iyyon is identified with a site near Marj-Ayoun, north of the twentieth-century border between Lebanon and Israel, Abel-beth Maacah is generally taken to be at Abil el-Qamḥ, just south of Iyyon, Kedesh (of the Galilee) is located at Tel-Kadis, just west of the Huleh’s northern tip, and Hazor is at the well-excavated site of Tel al-Qadaẖ, west of the Huleh’s southern tip.24 The destruction at Hazor is well documented in the archeological record, with stratum V ending in complete destruction, dated to 732 BCE.25 The archeological record at Abel-beth-maacah also shows a gap during the period after 732 BCE.26 The destruction in the area is not limited to the sites listed in the Biblical records: Beth-Saida, on the Galilee/Golan border on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee, is an illustrative example of sites in the region which were destroyed in the Assyrian conquests.27

The only site which does seem to have continued settlement after 733 is Tel el-Qadi, the site of Biblical Dan. The city gate of Dan was destroyed in the middle of the eighth century. Based on the nature of that destruction, Biran attributed it to the earthquake in the time of Uzziah (approximately 760 BCE). This earthquake did not end settlement in the city, nor did the destruction by burning of part of the city some years later. In the seventh century stratum, excavators found buildings, a large number of storage juglets, and an ostracon with the inscription lb‘l plt.28 Stern noted, however, that the seventh-century stratum was “probably unfortified,” and he attributes the destruction of the earlier stratum to the Assyrians, not to the earthquake.29

Standard Assyrian practice would not have involved the exile of all of the Israelite population of Hazor, Kedesh, and surrounding regions. The long-range strategic goal of this particular portion of the Assyrian campaign was clearly economic: Assyria sought to ensure control over this important trade-route. It follows that the wealthier portions of the population, those who engaged in trade and distribution of surplus goods, would be the ones to be exiled. Despite the absence of total exile, the remaining population’s economic life was severely disrupted.30 Those remaining became subsistence farmers, for whom preservation of culture may have been less of a priority. This is consistent with the findings of a survey of Upper Galilee sites conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority, published in 2001. While twenty-eight out of 36 rural Iron II sites continue into the Persian period, it is clear that there is a significant movement of population. Settlement decreases in the western hills of the Upper Galilee, and continues or increases in the eastern mountains of the upper Galilee, in sites southeast of Dan and in the region of Mount Meron.31

The evidence, while showing retention of rural sites in the eastern mountains of the Upper Galilee, does not establish a clear case for settlement continuity of Israelites in the Upper Galilee from the Biblical period to the post-Biblical Period. That retention of settlements does not indicate ethno-linguistic continuity may seem surprising, but scholars have offered convincing reasons for doubting such continuity in this region. Frankel, Getzov, Nimrod, and Aviam argue that since Phoenicians dominated the region in the Persian and Hellenistic periods, and since there is no change in settlement patterns in these periods, this shift in the ethnic composition of the region is most likely connected to the movement of population at the end of Iron II.32 This is consistent with the retention of settlements: the fact that some descendants of Israelite settlers continued to inhabit this mountainous region does not demonstrate that they retained their linguistic culture. They may have assimilated into the Phoenician ethnic element which began to dominate the region, or they may have been displaced by Phoenician settlers.

The processes leading to this assimilation or displacement seem to have begun already in the period of the Assyrian conquest. The eastern Upper Galilee, because of its importance in trade, was the site of an Assyrian administrative center. Evidence for such a center is found in the Assyrian building at Stratum III in Hazor Area B, and at the nearby Assyrian building at Ayyelet ha-Shahar, which has many features similar to Assyrian palaces.33 While the Assyrian administrators would not have suppressed the linguistic traditions of the native inhabitants, they would have required that the farmers distribute any surplus to support the Assyrian administration, and would have configured the trading patterns in such a way as to support Assyrian imperial aims. The importance of Tyre in the economy of the Assyrian empire is amply demonstrated by the priority the Assyrians attached to conquering Tyre, and by the Qurdi-ashur-lamur letter, in which the Assyrians asserted control over the export of cedar.34 The economic importance of Tyre would have required that agricultural surpluses would be directed to Tyre. Trade with Tyre would attract Phoenician traders, and would increase Phoenician linguistic and cultural influence on inhabitants of the region.

Thus, it is difficult to demonstrate ethnic and linguistic continuity in the eastern Upper Galilee on the basis of the retention of settlements in this area. The conclusion of Jonathan Reed, viz., “There is simply an insufficient amount of material culture in the Galilee from after the campaigns of Tiglath-Pileser III to consider seriously any cultural continuity between earlier and subsequent centuries” appears correct. However, I cannot agree with his reference to possible Assyrian administrative buildings (emphasis in the original), or with his statement that there were “no villages, no hamlets, no farmsteads, nothing at all indicative of a population that could harvest the Galilean valleys for the Assyrian stores.”35 Much of the population was not exiled, but all of the evidence suggests that the Phoenician language became predominant.

3 Archeological Evidence: Israelite Settlement in Iron Age Lower Galilee

What remains is the evidence from the Lower Galilee. Unlike in the Upper Galilee, we have clear and unmistakeable archeological evidence for Israelite settlement in the Iron II period, in two areas. Such settlement appears first in the 12th and 11th century, in the central part of the Lower Galilee, the region known in the Bible as the inheritance of Zebulon, a series of east-west dolomite ridges with very fruitful valleys separating them, and then, in the 10th and 9th centuries, in the eastern part of the Lower Galilee, the region of Issachar, consisting of basalt-covered plateaux, with steep wadis.36 Here the archeological evidence for the Assyrian exile of 733–732 is both stark and pervasive. No Biblical text mentions specific cities in the Lower Galilee from which Israelites were exiled in these years, but we have both Assyrian texts and archeological evidence for the exile. Both show a contrast to the Upper Galilee, in which the Assyrian campaign was conducted mostly along the main north-south road. The Assyrian campaign in the Lower Galilee penetrated more deeply. Sites off of main roads seem to have been sacked by Assyrian troops and the population exiled. The annals of Tiglath-Pileser, as collated by Tadmor, list seven towns:

of the 16 districts of Bit [Humri], I ... [x captives from the city of ...]bara, 625 captives from the city of ..., [x captives from the city of] Hinatuna, 650 captives from the city of Ku ..., [captives from the city of Y]atbite, 656 captives from the city of Sa ..., 13,520 [people] with their belongings [I carried to Assyria], the cities of Aruma and Marum [situated in] rugged mountains ...37

The numbers of captives from the individual towns are relatively small, but the total number of captives is quite high, 13,520. Even given that these numbers are exaggerated, it suggests a campaign in which many towns were exiled.

Four of these towns can be identified with relative certainty. Hannaton is clearly to be identified with Tell el-Badawia, located just north of the Bet-Netofa valley in lower Galilee, and Yotbah with the nearby site of Yotfat, known from Josephus. The ending - bara probably refers to Akbara, near Tzippori. 38 Aruma is presumably the “Rumah” of 2 Kings 23:6, and may be Khirbet el-Wawiyat in the Bet-Netofa valley or Khirbet Rumeh on the southern slope of the same valley.39 Marum’s locations is uncertain, but both it and Aruma are identified by the Assyrians as located in the mountains.40

Hannaton, Yotbah, Akbara and Aruma are clustered together on and near the Darb el-Hawarna, an important east-west road through the Lower Galilee in modern periods. It connects Akko to the fords of the Jordan south of the Sea of Galilee, near where the Jordan meets the Yarmuk. Oded has shown that it was a significant road already in the Biblical period, when it was used as a camel caravan road connecting the fertile agricultural areas in the north of Transjordan to the seacoast.41 Hannaton is located directly on this road (as is Tel Qarne Hittin, a possible site of Marum). Akbara near Tzippori is located only about 3 km south of Hannaton, and Yotbah is a similar distance to the north of Hannaton. Kh. el-Wawiyat is located about 4 km ENE of Hannaton.

Although Darb el-Hawarneh was not important for trade with the Assyrian heartland, it was an important internal route in Syro-Palestine. The focus on this area seems consistent with the Assyrian need to control local trade, and ensure that it was routed and re-configured to serve the interests of the Assyrian empire.

But it is harder to understand the reason for Assyrian activity off of major roads. The most extensively-documented example of such activity is the archeological evidence from Tel Rosh Zayit, excavated by Zvi Gal and Yardena Alexandre. Despite its distance from major roads, this Israelite site was completely destroyed by fire in 733–732.42 The site is located 10 km north of Hannaton, about 6km NW of Yotbah, and it is not clear why the Assyrians would intentionally send a force to such an out-of-the way site, in order to destroy it. Destruction of such out of the way sites does not accord with the usual Assyrian military practices in the period of Tiglath-Pileser III.43

The best explanation for this activity seems to be a particular interest in punishing the kingdom of Israel. Israel under Menahem had paid tribute to Tiglath-Pileser III in 738, but subsequently rebelled under Pekah. The prior loyalty of Israel, and its subsequent defection under an anti-Assyrian leader, may have caused Assyria to launch an attack of unusual destructiveness in 733 as a warning to other neighboring kingdoms.

There is good reason to believe that the extensive destruction at Rosh Zayit was replicated in other sites in the central part of Lower Galilee. Recent salvage excavations near Tel Tzippori show that immediately after the 733–732 destruction, survivors formed small one-period settlements away from historic towns. Thus, a few kilometers north of Tel Tzippori, Zvi Gal excavated an early 7th century site which was used for a single period, and then abandoned.44 This may have been a sort of “refugee camp” established by survivors of the Assyrian destruction, who then moved elsewhere. Where did they move? That is the real question, for which we have little evidence. They clearly did not re-settle many of the towns occupied in the 9th and 8th centuries, for the demographic map of the Lower Galilee changed completely as a result of the events of 733-732. 45 It is clear that in the central part of the Lower Galilee, there was no continuity of Israelite settlement after 732. The evidence from the destruction at Tel Rosh Zayit suggests that in other parts of the Lower Galilee, there may also have been widespread destruction, and the one period sites near Tel Tzippori suggest significant population movements after 732.

4 Archeological Evidence: Settlement in the Galilee in the Persian Period and Later Periods

Many of the sites abandoned after 732 remained abandoned until the Persian period. But the re-settlement in the Persian period had a very different character than the Iron Age settlement. Already in 1973, Ephraim Stern remarked that the re-settlement of the Lower Galilee in the Persian Period seems to bear Phoenician influence.46 This accords with the limited textual evidence we have for the demographics of the Lower Galilee in the Persian Period. In the Eshmunazor funerary inscription, dated to the middle of the fifth century BCE, Eshmunazor, king of Sidon, vaunts the land-grants accorded to him by

, the Persian king, probably Artaxerxes I. He describes how land at Dor, at Jaffa and in the Sharon were given to him, and calls them

, the Persian king, probably Artaxerxes I. He describes how land at Dor, at Jaffa and in the Sharon were given to him, and calls them

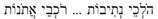

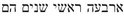

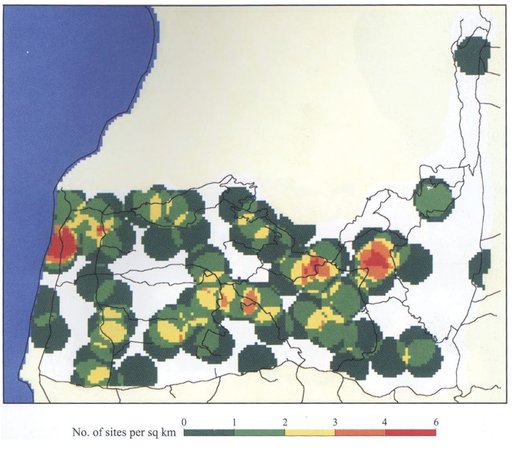

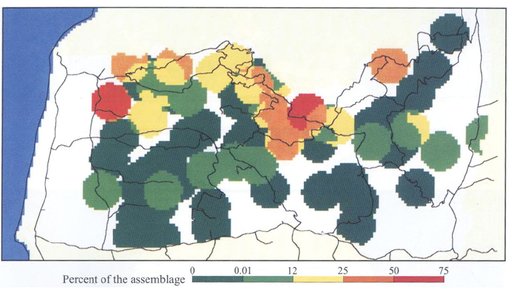

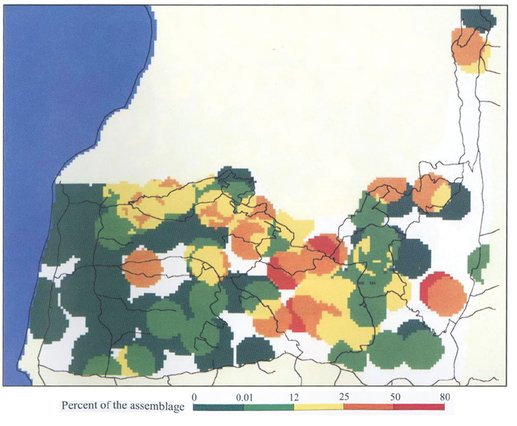

.47 These were certainly given to him to serve as an agricultural hinterland, as a breadbasket from which Sidon could draw sustenance. Having expanded as far south as Jaffa (where the hamra soil is of limited agricultural value for grain) it stands to reason that Sidon would first seek to draw on the far more proximate and fertile lands of the Lower Galilee, especially its central part. The Phoenician city-states flourished in the Persian period, and their wealth was shared with the agricultural hinterland in the Galilee, which formed their natural breadbasket and local trade provider. Stern’s statement also accords with the study by Frankel, Getzov, Aviam and Degani of the demographic geography of the Upper Galilee in this period. Above, I noted that the Persian period saw a continuation of the increase in settled areas in the Mount Meron area. At the same time, there was an increase in the number of sites in the coastal plain (Fig. 3).48 These two main settlement areas were clearly linked through their material culture, which attests to a trading pattern, moving from the Phoenician cities on the coast into the eastern hills. This can be seen from the distribution of the Phoenician jars of the Persian period. The distribution of these is densest in the coastal areas around Achziv and northwards, but they clearly move into the eastern hills, forming up to 50% of assemblages in the center of Upper Galilee, and up to 25 % at some eastern sites (Fig. 4).49 At the same time, the Galilean Coarse Ware, which seems to originate in Mount Meron and points east, is shipped westwards towards the Phoenician areas, forming between 12 and 25 % of assemblages in the areas near the coast (Fig. 5). Further evidence of Phoenician cultural penetration of the Mount Meron area in the eastern Galilee comes from Mizpe Yamim (located, as its modern name implies, right in the middle of Upper Galilee, at the peak of a mountain in the Mount Meron region). Although the vast majority of the pottery found in the Persian period stratum was Galilean coarse ware, the cult practiced at the local temple was Phoenician. This attests to an interpenetration of the Galilee, with Phoenician practices moving eastwards, even as the pottery of the Mount Meron area was shipped westwards.50

.47 These were certainly given to him to serve as an agricultural hinterland, as a breadbasket from which Sidon could draw sustenance. Having expanded as far south as Jaffa (where the hamra soil is of limited agricultural value for grain) it stands to reason that Sidon would first seek to draw on the far more proximate and fertile lands of the Lower Galilee, especially its central part. The Phoenician city-states flourished in the Persian period, and their wealth was shared with the agricultural hinterland in the Galilee, which formed their natural breadbasket and local trade provider. Stern’s statement also accords with the study by Frankel, Getzov, Aviam and Degani of the demographic geography of the Upper Galilee in this period. Above, I noted that the Persian period saw a continuation of the increase in settled areas in the Mount Meron area. At the same time, there was an increase in the number of sites in the coastal plain (Fig. 3).48 These two main settlement areas were clearly linked through their material culture, which attests to a trading pattern, moving from the Phoenician cities on the coast into the eastern hills. This can be seen from the distribution of the Phoenician jars of the Persian period. The distribution of these is densest in the coastal areas around Achziv and northwards, but they clearly move into the eastern hills, forming up to 50% of assemblages in the center of Upper Galilee, and up to 25 % at some eastern sites (Fig. 4).49 At the same time, the Galilean Coarse Ware, which seems to originate in Mount Meron and points east, is shipped westwards towards the Phoenician areas, forming between 12 and 25 % of assemblages in the areas near the coast (Fig. 5). Further evidence of Phoenician cultural penetration of the Mount Meron area in the eastern Galilee comes from Mizpe Yamim (located, as its modern name implies, right in the middle of Upper Galilee, at the peak of a mountain in the Mount Meron region). Although the vast majority of the pottery found in the Persian period stratum was Galilean coarse ware, the cult practiced at the local temple was Phoenician. This attests to an interpenetration of the Galilee, with Phoenician practices moving eastwards, even as the pottery of the Mount Meron area was shipped westwards.50

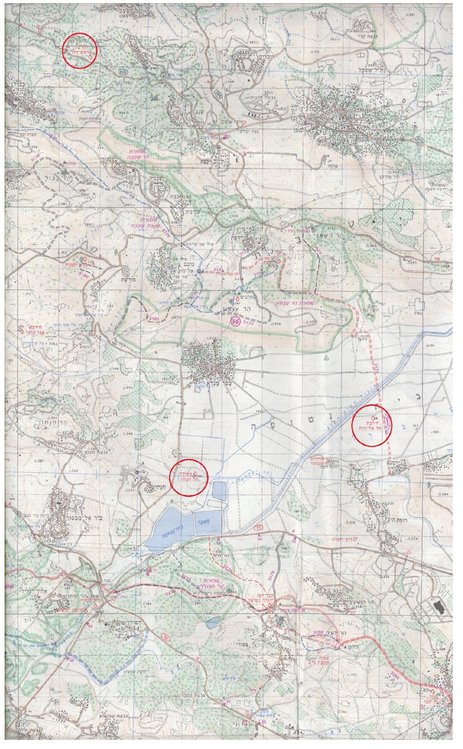

Fig. 2: Excerpt from map no. 3, “Lower Galilee and the Valleys” (published by Israel Trails Committee of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel, 1996. Reproduced with permission).

Fig. 5: Distribution of Galilean Coarse Ware, Persian and Hellenistic Periods. (Frankel et al., Settlement Dynamics and Regional Diversity in Ancient Upper Galilee, plate 28. Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority).

Turning to the Hellenistic period, we can supplement this archeological survey with some very limited textual evidence. This picture of a Phoenician population along the coast, which is gradually penetrating into the interior of the Galilee, is reflected in 1 Maccabees 5:14, in which the Jews of Galilee are said to tell Judah Maccabee that the Phoenicians of Tyre, Sidon, and Acco have gathered to annihilate them. Aviam has argued that the “Baraita of the Boundaries of Eretz-Israel” reflects Jewish settlement patterns in eastern Upper Galilee and in Lower Galilee in the first century BCE51 This is also reflected in Josephus, in Jewish War 2.21, 588-9, who describes how his nemesis, John of Giscala, gathered gentiles from Tyre to lay waste to Jewish towns in the Galilee. The picture of Jews living in the eastern Galilee, especially in the Lower Galilee, also finds expression in the Gospels.52

5 Origins of Galilean Jews in the Rabbinic Period and the Question of Mishnaic Hebrew

Where did the Galilean Jews mentioned by 1 Maccabees and Josephus come from? Lack of evidence prevents us from reaching any definitive conclusions. The archeological record does not support the hypothesis of continued Israelite /Jewish settlement in the Galilee from the Biblical period to the Hellenistic period. The combination of textual and archeological evidence shows that in the Persian and Hellenistic period, the interior of the Galilee had a significant trade with the coastal region of the Galilee, and shared the wealth of the coast. Economic upswings invariably draw population from other regions, and it is possible that the Jews living in the interior of the Galilee in the Hellenistic period arrived there during and due to this period of regional economic growth.

This leads back to the question of the influences on Mishnaic Hebrew. While it is possible that Mishnaic Hebrew is the dialectical continuation of northern Biblical Hebrew, the evidence suggests that more weight ought to be given to Phoenician influence. The Phoenician cultural and economic influence in the Galilee during the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods makes it clear that Galilean Jews in these periods would have had ongoing contact with the Phoenician language. It is possible that the Phoenician directly influenced any Hebrew spoken by these Jews, and that some features of Mishnaic Hebrew result directly from this influence.