But I have judged important the very difficult creation of poems and fiction which even a century ago were—and are now—bearers of a hot burden.

—GWENDOLYN BROOKS, NEGRO DIGEST, 1966

GWENDOLYN BROOKS CAME of age as a writer in Chicago when the Communist Party had already established a militant presence and voice in support of black civil rights. However minimal her early left-wing political affiliations might have been, scholars of the literary Left identify Brooks at the center of the Chicago Negro Left Front in the 1940s, which the literary historian Bill Mullen (1999, 10) describes as “independent of the Communist Party but largely symbiotic with its popular front objectives and aspirations.” Although Brooks was probably never a member of the Communist Party, there are always a fair number of communists and leftist radicals dotting the landscape in the reports of her cultural and social activities in the 1940s and 1950s. The literary historian James Smethurst (1999, 165) situates Brooks within most of the important cultural networks of the Left—from the Left-led National Negro Congress and the League of American Writers to the Left-influenced South Side Community Art Center and the Left-led United Electrician and Machine Workers Union and to the left-wing editors and writers who promoted her early career. Even the black nationalist poet and critic Haki Madhubuti, though he disparages its significance, acknowledges that the Left was at least a brief stop on Brooks’s career path: “She was able to pull through the old leftism of the 1930s and 1940s and concentrate on herself, her people and most of all her ‘writing’” (2001, 82).

1 The consensus among scholars of the Left is that Brooks was a part of a broad coalition of mainly black artists, writers, and community activists who were making their own history of radical black struggle, which exceeded, transformed, and expanded Communist Party–approved aesthetics but cannot be divorced from its influence and support. What I hope to show in this chapter is that in her work of the Cold War 1950s, mainly in her 1953 novel

Maud Martha and in several poems in her 1960 poetry volume

The Bean Eaters, written in the late 1950s, Brooks managed to balance a black leftist political sensibility with an investment in modernist poetics that produced, during the Cold War 1950s, what I call, with some caution, her leftist race radicalism. I am pursuing this course for many reasons, the first in answer to Brooks’s own call to poets to remember the past, no matter how controversial or problematic: “Think how many fascinating human documents there would be now, if all the great poets had written of what happened to them personally—and of the thoughts that occurred to them, no matter how ugly, no matter how fantastic, no matter how seemingly ridiculous!” I am therefore piecing together these fragments of Brooks’s leftist past, much of which she herself left unrecorded. I want to show her work as an example of the long left-wing literary radicalism that, especially for Brooks, extended into the 1970s and has been dwarfed by the attention to her black nationalist period, which seemed to require severing all connection to a left period in which she was a central player.

BROOKS IN THE CHICAGO BLACK POPULAR FRONT

Brooks’s own statements, particularly in her first autobiography,

Report from Part One (1972), have erased or masked signs of her relationship with the Left.

2 The friends and colleagues she socialized with in the 1940s and 1950s—artists and writers like Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, Ted Ward, Langston Hughes, Margaret Taylor Goss (later Margaret Burroughs), Frank Marshall Davis, Paul Robeson, and Marion Perkins—leftists, communists, and fellow travelers—are remembered in one-and-a-half pages in

Report from Part One as “merry Bronzevillians,” with no reference to their politics; they may be party guests and partygoers but never Party members. Consider how Brooks carefully parses her political leanings in an essay about Bronzeville she contributed to the 1951 issue of the mainstream magazine

Holiday. Though she covers a wide range of issues of black life in Bronzeville, beginning with the stories of the economically depressed and the consequences of poverty on children, she opens with a critique of the assumptions underlying the term “Bronzeville”: “something that should not exist—an area set aside for the halting use of a single race.” In “another picture of Bronzeville,” she depicted the exciting parties there, specifically noting that she did not mean the “typical” black bourgeois ones, which she called, ironically, “soulless,” but the “mixed” parties that included whites and blacks. Though, as in

Report One, she does not label them politically, many of the guests, like the host, the sculptor Marion Perkins, were avowed communists or deeply Left enough to be considered fellow travelers: Ed and Joyce Gourfain, Willard Motley, Margaret and Charles Burroughs. Joyce Gourfain was a former lover of Richard Wright, and both Gourfains knew Wright from their days in the John Reed Clubs; both were certainly Communist Party members.

3 Both Margaret and Charles Burroughs were close to the Party, and Brooks hints at that in

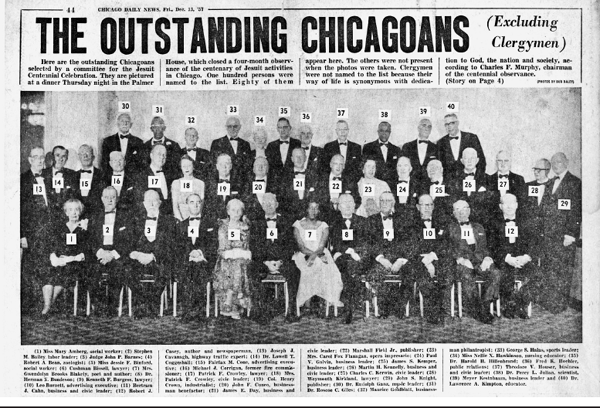

Report One, describing Margaret’s radicalism with a dictionary definition: “then a rebel, [who] lived up from the root” (1972, 69). Lester Davis, named in the Brooks article as a Chicago teacher, photographer, and journalist, was also at the time the executive secretary of the Chicago Civil Rights Congress, a position that would have gone to a CP member or close ally. Richard Orlikoff was a leftist attorney who defended an Abraham Lincoln Brigade member against HUAC. Also there were the African American physicist Robert Bragg, later a member of the faculty of the material science department at Berkeley, and his wife Violet. In the oral interview Bragg did for the Berkeley archives, describing himself as “a closet radical,” he speaks of his attraction to communism and his early friendship with Brooks, probably through the NAACP Youth Council. The only reference Brooks makes to the politics of these mostly leftist merrymakers is a series of ironic and mocking comments that imply but downplay the political tenor of their conversations. In her signature elliptical commentary on their conversations, Brooks reports that “Great social decisions were reached. Great solutions, for great problems” were debated over “martinis and Scotch and coffee” (1972, 68). In the photograph that accompanies the front page of the

Chicago article, Margaret Burroughs is shown strumming her guitar “for her artist-writer friends,” and Brooks, who may well have been in that audience, was, as we see from these alternative “reports,” at least for a time in the late 1940s and early 1950s, quite comfortably situated within the intimate circles of these Chicago Marxist bohemians.

One of the major Brooks biographers, her friend George Kent, insists that Brooks was too thoroughly “attached to the certainties of her upbringing, Christianity, and reformist middle-class democracy” to have espoused radicalism, but even he admits that she was within the orbit of the Left artists and writers during the 1940s. In her apprenticeship years, Kent notes that Brooks joined the NAACP Youth Council, which he says was “the most militant organization for black youth except for organizations of the Left” (1990, 42). As a Youth Council member, Kent says Brooks was spirited along by the more politically engaged members, such as her friend the artist and writer Margaret Taylor (later Goss, then Burroughs), who, along with Brooks, joined in antilynching protests, marching along with the other protesters through the streets of Chicago, wearing paper chains around their necks to symbolize the racial violence of lynching (44). That protest became the catalyst for one of Brooks’s earliest social protest poems. Margaret Burroughs, a lifelong friend, lists Brooks among the organizers of the one-day “Interracial South Side Cultural Conference” in 1944, which included Burroughs herself, as well as other black leftists—the poet Frank Marshall Davis, the sculptor Marion Perkins, Negro Story’s editor Fern Gayden, the playwright Ted Ward—and the white radical artists Sophie Wessell and Elizabeth McCord. According to the cultural historian Bill Mullen, when Burroughs recorded her recollection of the conference, she referred to all of its participants as progressive, which she said in a later unpublished letter to Mullen meant “Left wing to Communist,” which, apparently, included Brooks (1999, 101–102).

Despite her friendship with Burroughs, Mullen says that Brooks “escaped” identification as a writer on the Left, and he reads Brooks’s 1940s poetry as maintaining a skeptical and anxious distance from the political and cultural currents of the Left, as Brooks herself did. While I have not been able to locate any FOIA file on Brooks, the FBI had her in its sights. In the FOIA file of her friend Burroughs, agents accused Burroughs of introducing Brooks to the Left-led National Negro Congress and the National Labor Council and trying to radicalize her friend: “Margaret would later find that the FBI had kept a file on her beginning in 1937 and had labeled her as one of those attempting to influence Gwendolyn politically” (Kent 1990, 55).

I am not trying to turn Brooks into a communist, but I insist that her left-wing connections are an important part of her biography and essential to understanding the trajectory of her creative work. Like both Mullen and Smethurst, I am skeptical of any version of Brooks as political ingénue tagging along on Burroughs’s more radical coattails. Whatever her motivations for deflecting attention to the story of her early leftist political life, she sustained a number of leftist affiliations in the 1940s that furthered her literary career. She was mentored by leftist writers and editors, including Edwin Seaver, a founder of the Marxist journal

New Masses and a former literary editor of the

Daily Worker, who included work by Brooks in his

Cross Section anthologies in the middle and late 1940s (Smethurst 1999, 165). Another important left-wing connection for Brooks during the 1940s was the communist-led League of American Writers, formed when the CP disbanded the John Reed Clubs. In his memoir of the League, Franklin Folsom, the league’s executive secretary and a communist, lists Brooks in his memoir as a member, along with Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Arna Bontemps, Countee Cullen, Frank Marshall Davis, Ralph Ellison, Margaret Walker, and the openly communist Ted Ward and Claude McKay, all of whom would have been considered on the Left in the 1930s and 1940s (Franklin 1994, 75). By her own account, Brooks was deeply involved in the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC), a center of the Chicago black Left, where she studied poetry and modernism under a white mentor, the poet and “upper-class rebel” Inez Cunningham Stark (Melhem 1987, 9). Lawrence Jackson notes that she moved in intellectual crowds with a number of leftists: Ted Ward, Fern Gayden, Davis, and Edward Bland, all former members of the South Side Writers Club, which had been founded by Richard Wright in his communist days (206).

4 When Harper’s asked for Wright’s recommendation for Brooks’s first volume of poetry, he wrote back to the editor Edward C. Aswell, on September 18, 1944, recommending the book highly, asking for one long poem to unify the collection. He also recognized and confirmed the poems’ engagement with a Marxist aesthetics that demanded a focus on black cultural and communal life: “They [the poems] are hard and real, right out of the central core of Black Belt Negro life in urban areas” (cited in Fabre 1990, 185). When she turned to autobiography in

Report from Part One, Brooks represented her life in the 1940s and 1950s in terms of marriage, children, poetry, and parties, the only clue to her leftist life being the communists, leftists, fellow travelers, and radicals who attended those parties. If Brooks was simply naïve, and I doubt that she was, she certainly took her early political life seriously enough to deflect attention away from her substantial ties to the Left.

BROOKS’S EARLY LEFTIST POETRY

If we document Brooks’s writing career from the late 1930s during her Negro Popular Front period, rather than starting with her first published volume of poetry in 1945, the early traces of the Left in her writing are evident. In 1937, when she was just twenty years old, Brooks submitted her first poem, “Southern Lynching,” to the NAACP journal Crisis, which, in line with 1930s Popular Front politics attacking racism, produced features on lynching in almost every issue in the 1930s. Published in the same year that Burroughs was allegedly “radicalizing” Brooks and when Brooks was engaged in antilynching protests, the poem is aligned, in theme and tone, with Negro Popular Front politics. In this poem, there is none of the detached narratorial consciousness that Smethurst describes as characteristic of Brooks’s poetry of the 1940s and 1950, almost no sign of the narrative distance and indirectness of her later style. The narrator describes the lynched body in detail: dried blood on rigid legs and long / Stiff arms,” the still open eyes stare as “merry madmen” laugh and sing. The poem also anticipates Brooks’s use of irony in its intertwining of the bloody body, the lynchers singing, and the image of the soft pale evening darkening, with its night-breeze “flow[ing]” and the “first faint star” glowing “coldly” above the “strange and bloody scene.” The desecration of the body is complete when one of the lynchers “treats” his young child to “a souvenir / In form of blood-embroidered ear.” But the poem ends with the focus on another “youngster,” the son of the murdered man, waiting for his father’s return:

Back in his hovel drear, a pair

of juvenile eyes watch anxiously

For a loved father. Tardy, he!

Tardy forever are the dead.

Brown little baby, go to bed.

Here the speaker’s focus on the grisly details of the lynching scene allows no distance between the speaker, the victim, and his attackers, and, in typical social protest style, the speaker’s emotional investment also demands the reader’s empathy and moral outrage. I can find no evidence that Brooks ever referred to this poem in her commentary about her work or in her public readings. As a kind of Brooksian representational history, however, Brooks’s lynching poems help mark the the movement of her work from leftist social protest to modernist formalism, as “Southern Lynching” is clearly in the vein of 1930s social protest. Two other lynching poems, “The Ballad of Pearl May Lee,” from her first published volume, A Street in Bronzeville (1945), and “A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon,” from The Bean Eaters (1960), based on the lynching of the fourteen-year-old Emmett Till, suggest the modernist directions of her work. In both of these later poems, which she regularly included in her public readings, Brooks is thoroughly modernist, revising a conventional form—the ballad—and offering a feminist slant that takes on the almost always absent viewpoint of the woman victim. “Mississippi Mother” is told from the point of view of the wife of one of Till’s killers, herself a mother of two small children, somewhat stunned by her new role as the wife of a child killer. Emmett’s mother, Mrs. Mamie Till Bradley in real life, “loiters” as the Bronzeville mother throughout the poem, the mother of the killed boy, the image the white mother cannot ignore.

“The Ballad of Pearl May Lee” was first published in the left-wing

Negro Quarterly in 1944 (Jackson 2010, 205) edited by communist Angelo Herndon and Ralph Ellison in his proletarian days. The poem takes the viewpoint of the black woman whose lover is lynched because of his involvement with a white woman and includes the almost inadmissible representation of the black woman’s sexual jealousy and desire to be avenged by her lover’s murder. As Jacqueline Goldsby (2006, 1–4) has so superbly argued in

A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature, the Pearl May Lee lynching poem shifts the focus of the conventional lynching story in several crucial ways: it is set in the North, it narrates the black woman’s anger over her lover’s desire for “the taste of pink and white honey, and it protests not white racial violence but a black man’s desire for white and light-skinned women, which, in this case, has put Pearl’s lover in the crosshairs of a white lynching mob. Yet, even as the Pearl May Lee and “Bronzeville Mother” poems challenge the admittedly masculinist protest tradition, both recall and revise the politics of the cultural Left that brought racially instigated lynching to the foreground and made it a centerpiece of leftist protest. These markers of Brooks’s indebtedness to the 1930s (and 1940s) Left still remain in her work, but these connections have disappeared from nearly all Brooks commentary, including her own.

5The great and irretrievable loss is that we will never have Brooks’s own probing exploration of her place in a community of literary and visual artists committed both to social change and to formal experimentation within the community-based orientation of the Chicago Left Cultural Front. That community made the Chicago Negro Cultural Front a particularly hospitable climate for an artist interested in combining artistic experimentation and a radical black perspective. Many of the friends and colleagues with whom she socialized and worked, such as the visual artists Elizabeth Catlett and Charles White and the writers Langston Hughes and Margaret Burroughs, labored to balance their political and social concerns with formal experimentation. They did so with varying degrees of success and, in the case of White, against leftist resistance to modernist experimentation. Brooks was more fortunate. Her first book of poetry was reviewed by a socially conscious leftist imagist poet, Alfred Kreymborg, who managed that balancing act skillfully in his own work and recognized Brooks’s own attempts. Kreymborg published a rave review of

A Street in Bronzeville in the Marxist journal

New Masses. Calling the volume “original, dynamic, and compelling,” “one of the most remarkable first volumes of poetry issued in many a year,” and “a rare event in poetry and the humanities,” Kreymborg praised Brooks’s ability to “regard her people objectively in the face of every temptation to plead a cause in which she is deeply involved” (1945, 28). Repeatedly remarking on Brooks’s “technical skill” and “inventiveness,” Kreymborg flew in the face of Marxist orthodoxy, which disparaged 1950s art criticism as valuing “chic esthetic forms” and “formal gimmicks” that did not “inspire ‘progressive thinking’ and revolutionary social change” or “strong hopes for the working class.”

6 Kreymborg’s timing was auspicious: the review was published when formal experimentation was still seen favorably by

New Masses critics and just before the ascendancy of socialist realist orthodoxy in the early 1950s.

7 Brooks responded to the review in a 1945 letter to her friend and leftist activist-writer Jack Conroy, saying that she had been “very fortunate” in the reviews of the volume, specifically citing Kreymborg’s review: “There was a very generous one in

New Masses, September 4, by Alfred Kreymborg.” The year 1945 was a very good one for socially conscious imagist poets like Kreymborg and Brooks, and it was a moment when Brooks could and did bask in this recognition and acclaim from the Left.

8ERASING THE LEFT

Why, then, besides Brooks’s own reticence, has her relation to the Left been so difficult to establish? In considering this question, I am quite aware of the cultural amnesia that developed in the 1950s as the Cold War made it dangerous to acknowledge ties to the Left.

9 That amnesia was not only restricted to the “disappearing” of various poets or groups of poets but also, as Smethurst notes, applies to our ability to think or rethink the legacies (and contexts) of poets, for example William Carlos Williams, Hughes, Brooks, Kenneth Fearing, Muriel Rukeyser, Margaret Walker, and Robert Hayden, all of whom were part of the Left Popular Front in the 1930s and 1940s. For a number of reasons, Brooks’s “occluded” relationship to the Old Left is more difficult to tease out than that of most of the African American literary Left, some of whom have unusually open past and present ties to the Left and others who left behind obvious clues. But if Brooks has “escaped” identification as a writer influenced by the Left, that misconception has been most effectively facilitated by the saga of Brooks’s 1967 “conversion” to black nationalist radicalism (Smethurst 1999, 151)—a conversion tale that I believe to be apocryphal and misleading—and that, most problematically, required the rewriting of her earlier left-wing radicalism. Brooks’s more public movement toward black cultural nationalism in the 1960s and the elision of her connections to the Left have helped veil these earlier political affiliations and partly explain the dull conventionality of Brooks’s autobiographical narratives. I argue that in our failure to appreciate Brooks’s connections to the leftist cultural front of the 1940s, we also lose a sense of the innovative relationship Brooks forged in her work between a Left-inflected ideology and a modernist formal poetics.

The “rewriting” of Gwendolyn Brooks’s post-1950s political life by critics and reviewers reads as follows:

an apolitical Brooks, having been highly esteemed and richly rewarded by the white literary establishment for her early work, is baptized into black cultural and political nationalism by the young black militants she meets for the first time at the Second Black Writers Conference at Fisk University in 1967; having rejected her earlier connections with and submission to the white liberal consensus, she discovers her blackness and her radicalism within the (masculine) arms of Black Power and black nationalism. Brooks herself promoted this story in her 1972 autobiography

Report from Part One, describing the 1967 conference in almost mythical terms as an “inscrutable and uncomfortable wonderland” where the “hot sureness” of the black radicals “began almost immediately to invade” her and her new “queenhood in the new black sun” qualified her, finally, to enter “the kindergarten of new consciousness.”

10While Brooks undoubtedly perceived the black consciousness movements of the late 1960s and 1970s as life changing, as they were for many blacks of that period, the continual and uncritical recitation of the “conversion” narrative disconnects Brooks from her earlier political contexts and, indeed, even from her own remarks

at the 1967 conference. Brooks’s immersion in the baptismal waters of the ’67 conference may have

eventually caused her to reevaluate the relationship between her art and African American political struggle, but during her time at the conference she held firm to her earlier position, rejecting what she called “race-fed testimony” in art. In her prepared presentation at the conference, Brooks acknowledged the importance of race in black art: “every poet of African extraction must understand that his product will be either italicized or seasoned by the fact and significance of his heritage. How fine! How delightful!” But, she insisted—and this was said while she was still

at the conference, “I continue violently to believe [that] whatever the

stimulating persuasion, poetry, not journalism, must be the result of involvement with emotions and idea and ink and paper” (quoted in Kent 1990, 199). In what might be considered a statement of her own poetic credo and a modernist restatement of Du Bois’s double consciousness, she argued for the “double dedication” of black poets, addressing the “two-headed responsibility” they must have in order to respond to the “crimes” they cover but also to the “quantity and quality of their response to those crimes.”

Brooks eventually expressed her annoyance with these pronouncements about the “change” in her work. In a 1983 interview with Claudia Tate, when asked if any of her early works assume an “assertive, militant posture,” Brooks says emphatically, “Yes, ma’am…. I’m fighting for myself a little here because I believe it takes a little patience to sit down and find out that in 1945 I was saying what many of the young folks said in the sixties” (Tate 1983, 42). Later in the same interview Brooks repeats that she is “fighting for myself a little bit” as she moves to reshape the critical readings of her early work. Still later she says she is “sick and tired of hearing about the ‘black aesthetic,’” because “I’ve been talking about blackness and black people all along” (45–46).

11THE EVIDENCE OF THE LEFT

But if Brooks’s ties to the Left can be discerned in the friendships she developed, in her social life, and in her affiliations with Left organizations, what is less clear and more important is how to chart these ties in her work. Despite public statements that distance her from the politics and aesthetics of the Left, I argue that Brooks—like Hughes, Frank Marshall Davis, Melvin Tolson, Lorraine Hansberry, Julian Mayfield, Sarah E. Wright, John O. Killens, and many others that are rarely connected to the Left—was influenced by the aesthetics of the Popular Front and that we can see that influence most clearly in her struggling over the problem of how to negotiate a relationship between social realism and modernist experimentation. Brooks’s attempt to balance social concerns and modernism aligns her with other quite devout leftists, many of whom had “similarly complicated relationships” to “high” modernism.

12 Contrary to conventional accounts of artists on the Left, many felt that they had to balance their political and social concerns with the problems of realism versus formal experimentation. As I have shown in

chapter 2, White faced these issues in the 1950s as the Communist Party began to take a more rigid stance in their demands that art adhere to principles of socialist realism. The painter and sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, on the other hand, more easily accommodated her social and political concerns with modernist art techniques, almost certainly because of her location in Mexico among Mexican muralists—Diego Rivera and Francisco Mora (her second husband)—whose communist politics did not preclude modernist experimentations. In

Rethinking Social Realism: African American Art and Literature, 1930–1953, the cultural historian Stacy I. Morgan traces the way modernist innovation runs through the work of all the writers traditionally associated with social realist traditions. While these social realists—among them the poets and writers Frank Marshall Davis, Ann Petry, Robert Hayden, Lloyd Brown, and Gwendolyn Brooks and the visual artists Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett, and John Wilson—were intent on representing social change in their art and using art for social change, they were also experimenting with modern forms. In fact, as Morgan shows, African American visual artists exposed to the new media and materials through the Federal Arts Project were given their first opportunity for experimentation.

Reading Brooks back into a leftist political and artistic community enables us to track the continuities and discontinuities in her political and aesthetic development rather than being force-fed the tale of her sudden and unprecedented conversion to blackness and radicalism. As the cultural historian James Smethurst shows in

The New Red Negro, a superb analysis of the relationship between black writers, formal experimentation, and Popular Front cultural agendas, Brooks’s concern with issues of class, race, and gender oppression marks her as someone working in Popular Front traditions (Smethurst 1999, 179). With the aid of the lens of a slightly Left-tilted political biography, we can see that she was working out the formal and thematic issues that were important to many black Popular Front writers: how to represent the African American vernacular voice; how to represent African American working-class and popular culture; how to incorporate both high literary culture and social protest; and how to represent class, race, gender, and community. These are the signs of what Bill Mullen (1999) calls the “discursive marks” of the cultural and political Left. Even if, as Mullen insists, they are in coded and revised forms, they provide the evidence that Brooks’s political commitments were being formed at least three decades before 1967.

BROOKS’S 1951 LEFTIST FEMINIST ESSAY: “WHY NEGRO WOMEN LEAVE HOME”

In March 1949, five years after some of her closest encounters with the Left, Brooks was on her way to being recognized as a major poetic voice. She published a second book of poetry,

Annie Allen; received an excellent five-page review by Stanley Kunitz in the magazine

Poetry; and, in 1950, won the Pulitzer Prize for that volume, the first African American to win the award. At some point during the years 1947 to 1950, Brooks separated from her husband, Henry Blakely, also a poet, and had to consider how she would manage financially with a young child, son Henry Jr. (Melhem 1987, 82). By 1951, she had reunited with Henry and had a second child, Nora. At thirty-four years old and, perhaps, with the memory of that separation and what it meant to be an economically dependent wife, she published the essay “Why Negro Women Leave Home” in the March 1951 issue of

Negro Digest. It dealt with the inequalities facing black married women at home and at work. Under the bright lights of mainstream fame and praise, Brooks’s left-wing connections were hardly noticed, so it is not surprising that this little-known essay was never connected to the 1940s Communist Party debates over women’s issues, not even by leftist feminists.

13 As Kate Weigand (2001, 100) argues in

Red Feminism, the Party took a progressive stand on black women’s rights, arguing for black women’s permanent access to industrial jobs and protection against all forms of discrimination. In Party literature and in Party-sponsored educational forums, the Party featured articles about black women’s history, and in Left-organized schools, classes taught by progressive black women like Lorraine Hansberry, Claudia Jones, and Charlotta Bass focused on black women’s achievements and struggles, with the aim of empowering black women and making them central to the Party (109). As Weigand sums it up, “Communist leaders pushed rank-and-file members [especially in the 1950s] to act on their belief that all progressive people had a personal responsibility to support black women’s struggles and to welcome black women into the movement with open arms” (111). Communists, often those in black-dominated unions, worked to improve wages and conditions for black women workers, especially domestics, and to denounce the male chauvinism of left-wing writers and activists during the 1940s and 1950s that ignored these issues. Left-wing unions also had a hand in promoting black cultural production. The left-leaning United Electrical and Machine Workers Union, through the efforts of the black Chicago communist Ishmael Flory, funded the prize given by the journal

Negro Story, a prize Brooks won in the 1940s (Smethurst 1999, 165).

Brooks cites a number of reasons in this essay that Negro women were considering leaving their marriages, among them gold-digging husbands, in-law interference, male impotence, and their husbands’ affairs with other women (or men). But the central emphasis of the essay is on the liberating experience of a woman going to work during the war, earning her own income and experiencing “the taste of financial independence”:

her employer handed her money without any hemming and hawing, lies, rebukes, complaints, narrowed eyes—and without telling her what a fool she was. She felt clean, straight, tall [a description Brooks would use later for Maud Martha], and as if she were a part of the world. She was now “a fellow laborer,” deserving of respect and tact.

The language and rhetoric of the essay has the rhetorical ring of the communist movement’s position on the “Woman Question,” which hammered on the “triple exploitation” of black women, challenging them to “guard against male supremacist behaviors, to adopt egalitarian gender roles, and to live out their politics in their day-to-day lives at work, in their interpersonal relationships and at home” (Weigand 2001, 113). These subjects were most ably theorized by the high-ranking black communist Claudia Jones in her ground-breaking 1949 essay “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman,” which also challenged the failure of white communists to put their theories into action. In the left circles of

Negro Quarterly, the South Side Cultural Art Center, the National Negro Congress, or hanging out with her friend Margaret Burroughs, Brooks might very well have read Jones’s article (Weigand 2001, 113).

But, in critical ways, Brooks’s essay departs from the radical leftist critique that emphasized issues of unionization, class inequalities, solidarity with other women, demands for changes in the workplace, and the ultimate goal—freeing women for political struggle. Brooks was more interested in casting her acute eye on the psychological abuses in marriages and partnerships that do not often surface in politically left-wing material. Brooks lists the things a financially independent woman is able to do: buy a pair of stockings without her husband’s curses, buy her mother or father a gift without his hysterically shouted inquiries, take a college course or buy her child an overcoat without having to plan a strategic campaign or confront his condescending handout. She is aware of the emotional and psychic cost to women of staying in loveless or disappointing marriages because of financial dependence on their male partners. Despite what leftists might have considered the bourgeois concerns of the essay, Brooks calls for men to treat women as “fellow laborers” in language that evokes the politics and practices of the Left. “Why Negro Women Leave Home” begins to chart Brooks’s ironic relationship to the Left. Yes, she would draw on the language and ideology of the Left, but always in her own idiosyncratic, racialized terms. She could not assume the privileged positions of a white leftist feminist as empowered agent, nor could she assume the role of protector of black women in the industrial unionized workforce. She was a writer, a poet, an aspiring working-class black intellectual woman, a figure that could only be seen as anomalous in the 1950s, as her working-class women neighbors reminded her.

MAUD MARTHA: BLACK LEFTIST MODERNIST FEMINIST NOVEL OF THE COLD WAR

Brooks began working on her first (and only) novel,

Maud Martha, as early as 1944, and, with the help of Guggenheim awards in 1946 and 1947, submitted the manuscript, which her editor at Harper’s rejected as “too hampered by a self-consciousness more suited to poetry than prose” (Melhem 1987, 80). More submissions and rejections followed until final acceptance in 1953. Originally entitled

American Family Brown and constructed as a series of poems, the novel still demands to be read as one would read a highly complex, tightly structured poem. Composed of thirty-four short, imagistic chapters

14 that rely on a combination of stream of consciousness, interior monologue, free indirect discourse, dreamscapes, chapter headings that frame and order the narrative, and cryptic and unresolved chapter endings, it represents a black urban landscape not as realist landscape but as imaginative space, an allegorical landscape. Each chapter is filtered through the poetic, highly perceptive, sometimes claustrophobic self-consciousness of a black female subject. As the novelist Paule Marshall reminds us,

Maud Martha is the first American novel in which a dark-skinned, working-class black woman with a complex interior life appears as a main character (see Washington 1987, 403–404). Closely paralleling Brooks’s life, the novel covers Maud’s life from age six or seven until she is in her late twenties, roughly from 1924 to 1945. Brooks described the novel as a hybrid, part autobiography and part fiction: “Much that happened to Maud Martha has not happened to me—and she is a nicer and better coordinated creature than I am. But it is true that much in the ‘story’ was taken out of my own life, and twisted, highlighted or dulled, dressed up or down” (Brooks 1972, 191). The final chapter, “back from the wars!” is fairly optimistic, with Maud, though disillusioned with marriage (the domestic war), awaiting her soldier brother’s return from the war and contemplating the birth of her second child—scenes that were based on Brooks’s own experiences.

MAUD MARTHA AS “GHETTO PASTORAL”

Though there are now several leftist revisionist studies of Brooks’s poetry,

Maud Martha is nearly always read as unattached to any prior left-wing contexts. The cultural historian Michael Denning suggests three reasons for not seeing its radical possibilities: its lack of an “explicit ‘political’ narrative,” its “ethnic or racial accents,” and the Left’s failure to recognize the changing nature of the “working-class author” (1996, 235). Critics did not read a highly intellectual black woman—either author or subject—as an “authentic” representative proletarian. Brooks was identified as a black writer or a woman writer, not as a working-class writer—and

Maud Martha did not seem to fit (and, in fact, did not fit) the requirements of the conventional proletarian novel. The critic and writer Lloyd Brown, for example, a prolific reviewer of black writers for the left-wing press throughout the 1950s, made no mention of Brooks’s work.

15In an insightful and expansive theorizing of fiction he calls “ghetto pastorals,” Denning shows that Brooks’s 1953 novel fits quite comfortably in the black cultural Left—as a novel with the proletarian outlook and by a writer socialized in a working-class family and community (as Brooks was) but aspiring to an intellectual life. Like other writers of the ghetto pastorals (Richard Wright, Tillie Olsen, Philip Roth, Jack Conroy, Hisaye Yamamoto, and Paule Marshall, to name a few) Brooks is resistant to old forms, dissatisfied with the demands of naturalism, and increasingly drawn to experimental modernist fiction. Struggling for independence from the realism and naturalism of the novel, these writers needed a form, Denning argues, that could accommodate the contradictions of their lives: the geographic and psychological limitations of ethnicity or race, their uncertain and enigmatic futures during a still-segregated Cold War era, and the changing nature of their working-class lives (1996, 230–258).

16While I am in agreement with Denning on

Maud Martha’s leftist identity, I find myself throughout this chapter in an ongoing and as yet unsettled dialogue with Bill V. Mullen, specifically with his reading of Brooks’s poetry before the publication of

Maud Martha as more likely to exemplify a flexible and less militant definition of the leftist cultural front.

17 Mullen situates Brooks, as I do, at a moment after the war when black and white radicals alike could envision and expect critical and commercial success, thus experiencing along with those prospects “troubling uncertainty about the myriad dilemmas facing black American writers, activists, and cultural workers after the war” (Mullen 1999, 179). Mullen contends that Brooks inserts “stopgap measures” in her poetry that critique capitalism but do not enable radicalism, in some cases producing characters who have no way to apprehend or form the kind of collective resistance that might have been available in the radical collective of the South Side Community Art Center. The stasis that is characterized by employing “Prufrockian” (Mullen’s term) modernist themes of alienation and dislocation, images of passivity, and paralysis and stalled progress does not evoke the militant resistance of a traditional leftist politics; instead, these modernist effects register Brooks’s “ironic relationship” to the black cultural politics of the Chicago Front. While keeping Mullen’s reservations in mind, I maintain that Brooks’s critique of race, gender, and class in this novel, written at the height of Cold War repression, is a sign of radicalism, and I am inclined to agree with the literary scholar John Gery (1999), who says that Brooks’s use of parody “to convey the deep ambiguities facing those who live in black ghettos” is a “politically aggressive” and radical move. As Gery notes, we have to read her radicalism in this novel in the ways she combines modernist formal devices with subjects usually alien to modernism to expose “the very rhetorical structures of thought by which those oppositions stubbornly persist” (54).

Brooks establishes Maud’s working-class status in language designed to emphasize Maud’s finely tuned aesthetic sensibility. Her childhood home has “walls and ceilings that are cracked,” tables that “grieved audibly,” doors and drawers that make a “sick, bickering sound, “high and hideous radiators,” and “unlovely pipes that coil beneath the low sink” (Brooks 1953, 180). Although her parents are buying the house, where they have lived for fourteen years, the family waits in fear to see if Maud’s father, a janitor, as Brooks’s father was, will be able to extend the mortgage from the Home Owners’ Loan Association, staffed and owned, no doubt, by whites in this Jim Crow world. What she desires and fears losing is not simply homeownership but “the “shafts and pools of lights” that create the “late afternoon light on the lawn,” “the graceful and emphatic iron of the fence,” “the talking softly on the porch.” As teenagers in the early 1940s, Maud earns ten dollars a week as a file clerk, and her sister Helen, fifteen dollars a week as a typist (176), salaries that were several dollars below the minimum wage, which, in 1940, was forty-three cents per hour. As a married woman, Maud and her husband Paul move into a third-floor furnished kitchenette apartment, as Brooks did, two small rooms with an oil-clothed covered table, folding chairs, a brown wooden ice box and a three-burner stove, only one of which works, and a bathroom they share with four other families. The roaches arrive; the “Owner” will not make any changes; the couple will have to be satisfied with the apartment “as it is.” Maud’s disappointment with husband and marriage is the logical and inevitable adjunct to the gray, drab, and unsatisfying conditions of the home Paul is able to provide, so different from the traditions of “shimmering form, hard as stone” she had imagined for herself. As she thoroughly examines the ways in which working-class poverty erodes a marriage relationship, Brooks’s social concerns, aesthetically rendered, pervade the entire novel.

What distinguishes Maud from other black proletarian fictional characters is that she is a developing intellectual as well as being a proletarian; she is familiar with both working-class poverty and with more intellectual and academic pursuits. Maud makes specific references to the allure of such university literary canons as Vernon Parrington’s three-volume study of American literature,

Main Currents in American Thought, a fixture in U.S. graduate schools in the 1940s and 1950s. When Maud refers to “East of Cottage Grove,” that same racial dividing line between black and white that confines Bigger Thomas in Richard Wright’s

Native Son, it is not mainly in terms of physical space. Seen through the eyes of Maud’s second beau, David McKemster, east and west of Cottage Grove signify the cultural, intellectual, physical, and imaginary spaces of black limitation and white control that thwart the desires of an aspiring black intellectual, including herself, though she specifically names her “second beau”:

Whenever he left the Midway, said David McKemster, he was instantly depressed. East of Cottage Grove, people were clean, going somewhere that mattered, not talking unless they had something to say. West of the Midway, they leaned against buildings and their mouths were opening and closing very fast but nothing important was coming out. What did they know about Aristotle?

(44-45)

McKemster aspires to college, to moving away from the South Side, to an intellectual life where he would not only read Parrington’s

Main Currents in American Thought but could toss it around carelessly as one would a football—as he assumes privileged whites do. McKemster’s desire for access is undercut by his marginalized existence on Chicago’s South Side. He is ashamed of his mother, who takes in washing and says “ain’t” and “I ain’t stud’n you.” With ironic emphasis on the elitism of the word “good,” the narrator tells us that McKemster wants a good dog, an apartment, a good bookcase, books in good bindings, a phonograph with symphonic records, some good art, those things that are “not extras” but go “to make up a good background” (188). In striking contrast to Carl Sandburg’s tributes to the lustiness, power, and dogged vitality of the Windy City, the narrator (always through Maud’s consciousness) informs us that McKemster’s life on the South Side is not “colorful,” “exotic,” or “fascinating” but a place where “on a windy night” he (and perhaps Maud too) feels “lost, lapsed, negative, untended, extinguished, broken and lying down too—unappeasable” (187). The poet and literary scholar Harryette Mullen reminds us that here Brooks is employing the rhetorical device of synathroesmus, which consists of piling up adjectives, often as invective, to modify a noun.

18 Buried under this stack of adjectives, McKemster seems to lose any intrinsic qualities and is psychologically demolished by that overwhelming accumulation of negating modifiers until the final adjective. The final term, “unappeasable,” shifts the tone to focus on the need and desires of the “loser” rather than on his state of abjection, thus saving him from total annihilation. If Bigger’s crude references to white power structures more accurately describe the effects of white racial power and black powerlessness, Brooks’s critique is aimed partly at McKemster’s own pretensions but most severely at the integration ideologies of the Cold War 1950s, which promoted the notion that as blacks achieved sufficient intellectual and cultural weight they could become candidates for integration, even as the economics of segregation were rigidly maintained. Clearly, however, this narrator knows the meaning of and how to deploy synathroesmus and thus how to assert her own power.

Chapter 24, “an encounter,” the second David McKemster chapter, almost certainly meant to suggest the story “An Encounter” in James Joyce’s Dubliners, aligns Brooks with a quintessential modernist. Following the pattern of the other thirty-three chapters, the chapter is elliptical, about six pages long, narrated almost entirely in free indirect discourse, and focused relentlessly on Maud’s interior reactions, ending abruptly without conclusion or resolution. Now a young married woman and mother, Maud runs into McKemster on the campus of the University of Chicago, where they have both gone to hear “the newest young Negro author” speak. When McKemster sees two of his white college friends, he proposes that they go to one of the campus hangouts, and out of sense of obligation invites Maud, whom he introduces formally as “Mrs. Phillips” to his “good good friends.” McKemster and his friends proceed to carry on a conversation, which the narrator, channeling Maud’s inner thoughts, describes caustically as “hunks of the most rational, particularistic, critical, and intellectually aloof discourse” (272), into which they weave words like “anachronism, transcendentalist, cosmos, metaphysical, corollary, integer, monarchical” (274), words noted by the third-person narrator but intended to represent Maud’s resentment as outsider as well as her own private satisfaction that she too knows these terms.

The entire encounter is constructed around the question the young white woman (nicknamed Stickie) poses about the young Negro author they’ve come to hear: “Is he in school?” The question is subtle, posed in the argot of the college insiders, and intended to consolidate their intellectual superiority. It is such a loaded question that, before it can be answered, the narrator intervenes, inserting after Stickie’s question a veiled reference to the William Carlos Williams “red wheelbarrow” poem: “on the answer to that would depend—so much.” Here Brooks’s reveals her own knowledge of modernism and her critique of it. She adds a dash between “depend” and “so much” as if to alert the reader that she is quoting from and also rewriting the Williams poem. Remember that the poem depends on a series of material images: “a red wheel / barrow / glazed with rain / water / beside the white / chickens.” But there’s no concrete image in the Brooks chapter—the question evokes the elitism and snobbery through which people like Maud are excluded or included. The chapter suggests that the young woman’s question, “Is he in school?” allows these insiders to consolidate their power, giving them the power to measure the young Negro writer’s importance—for insiders both in and outside the text.

David answers “Oh, no,” and, assuming authority, assures his audience that the young Negro author “has decided” that “there is nothing in the schools for him,” that though he may be brilliant, may have “kicked Parrington or Joyce or Kafka around like a football,” “he is not rooted in Aristotle, in Plato, in Aeschylus, in Epictetus”—the classical traditionalists. (“As we are,” the narrator adds.) This interaction is channeled through Maud’s interior consciousness in order to convey Maud’s feelings of displacement in the university world and the coded terms by which her outsider status is conveyed. In this case, “so much depends” not on our appreciation of the material objects of the physical world as in the Williams poem but instead on our ability to read and critique the assumptions of hierarchical categories and vocabularies of exclusion. What we do know is that Brooks intended these narrative techniques to represent a protagonist “locked out” of white/ male/upper-class traditions. Deliberately reversing the godlike powers typical of male narrators and claiming her own insider authority, Brooks is also critiquing the male-dominated naturalistic tradition, in particular the social realism of texts like Wright’s

Native Son—and

Twelve Million Black Voices—with its reliance on representations of a static black collectivity.

19 The language of gesture in

Maud Martha forces us to develop our skills of observation and to learn to read a face or gesture without the privileged access sanctioned by realistic traditions—as one is required to read Joyce or Williams. Her silence here may indeed require us to read back to the accumulated injuries she has endured as a black female working-class intellectual throughout her life, as the chapter ends abruptly with a single-sentence, unmediated comment by the narrator: “The waitress brought coffee, four lumps of sugar wrapped in pink paper, hot mince pie.” On the other hand, what Maud has ordered replaces silence with her hot awareness (and perhaps even her own assumptions of a modernist smackdown of her so-called betters) of both the confectionery condescension at the table and her own disguised, repressed (minced) anger (275).

20MAUD MARTHA ROUGHS UP THE SMOOTH SURFACES OF COLD WAR CULTURE

Brooks was working both sides of the political divide in the 1950s. As I have indicated in the first part of this chapter, Brooks developed as a writer and activist in the leftist circles of the South Side Community Art Center while working with a group of black writers and artists committed both to social change and to formal experimentation. Beginning in 1941, their poetry instructor was Inez Cunningham Stark, “an elegant upper-class rebel from Chicago’s ‘Gold Coast,’” a modernist poet herself and board member at Poetry, who obviously helped send Brooks in modernist directions (Melhem 1987, 9). The minutes of the 1944 board meetings of the SSCAC, where Brooks was apparently workshopping her first novel, suggests that Brooks, now formally committed to a modernism in her poetry, was working out her method and intention for her first attempt at writing a fictional narrative. As the minutes indicate, the class was working that year on fiction concerning personal interracial relations, and Brooks is specifically mentioned:

The attempt is being made in these [meetings] to present the psycho logical story, to show what is in the minds of the persecuted or the persecuting if [

sic] Jim Crowism is depicted, to get inside the mental conflict which is set up individually by this thing called race. A number of new writers are developing in this group, two men working on their first novels, a journalist or two, and the winners of both first and second prizes for poetry in this year’s Midwest poetry awards, one of whom, Gwendolyn Brooks, has her first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville [

sic], released this last month by Harpers Brothers.

21

At the same time that she was workshopping at the leftist SSCAC, where race and modernism comfortably coexisted, Brooks was also negotiating with her white editor, Elizabeth Lawrence, and readers (probably white) at Harpers, as she tried, from 1945 to 1951, to get her novel accepted. Lawrence conveyed to Brooks the readers’ discomfort with Brooks’s treatment of race: “One reader liked the lyrical writing but was disappointed by the sociological tone and patent concern with problems of Negro life” (quoted in Melhem 1987, 81). Though Brooks proceeded to make changes, her editor continued to express concern about her representations of race: “It was proposed that the unpleasant experiences with whites be balanced by a positive encounter to justify the hopefulness she [Maud Martha] retains” (83). Lawrence thought that the hopefulness in the novel should be tied to Maud’s “positive” experiences with whites rather than to Maud’s growing awareness of and resistance to racism. In the final letter of approval for publication, Lawrence used the coded term “universal” to warn Brooks against too much emphasis on racial issues and “possible stereotyping of whites” in her future writing: “She hoped that the poet’s future work would have a universal perspective” (83–84). Lawrence suggested another change that confirms her biases. In the chapter where Maud is reading, Brooks had originally chosen a book by Henry James, one of Brooks’s favorite models for writing fiction, but Lawrence called that selection “improbable,” so Brooks changed it to the more popular and less highbrow

Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham. We might call to mind here that Brooks meant for her protagonist to be a racially marked, working-class, modern intellectual. Brooks was well aware of the way Lawrence was coding race, but, rather than softening her racial critique, she instead inserted a series of racially marked chapters. I argue that she was deliberately refusing the Cold War consensus on race—that black writers should minimize racial identity and racial strife in an effort to achieve “universality.”

The editor’s pressure on Brooks to soften her racial critique has to be understood in the context of late 1940s and early 1950s race liberalism. In her remarkable study of U.S. postwar racial change,

Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in New Racial Capitalism (2011), the cultural historian Jodi Melamed critiques the ways that new postwar racial orders, which she calls “official antiracist liberalism,” emerge during the Cold War, ostensibly to promote racial equality but in actuality to serve as technologies “to restrict the settlements of racial conflicts to liberal political terrains that conceal material inequalities” (xvi). Meant very clearly to repress and supersede the race radicalism(s) of the 1940s, “official antiracist liberalism” operated to stymie race radicalism and to substitute an official race order that would ignore material inequalities, restrict the terms of antiracism, promote “progress” narratives, and, in my terms, depoliticize antiracist work. Melamed argues that literary texts, often under the guise of protest narratives, were deployed to do this kind of race neutralizing—first, represent; then, destroy. As many scholars of the Cold War make clear, this kind of liberal antiracism sold well in the era of Cold War containment, anticommunism, McCarthyism, HUAC investigations, and FBI spycraft. As I show in

chapter 5, the CIA was operating domestically as well as internationally to carry out its policies of containment and repression, diligently and deviously infiltrating and manipulating African American cultural institutions. Cold War ideologies, often disseminated through the culture industry, permeated every facet of American life, particularly the media. In the massive drive to insure and justify the elimination of left-wing dissent, anticommunism was successfully installed as a permanent feature of U.S. democratic ideals to undercut political radicalism further.

Considering Melamed’s argument that literary texts were also purveyors of racial containment, there is even more reason to appreciate

Maud Martha as politically radical. Certainly, Brooks refused African American optimism about racial progress. Taken together, the thirty-four chapters in

Maud Martha form a textual indictment of the “Negro progress narrative,” as chapter after chapter reveals Maud’s discontent, impotence, and anger over Chicago’s racial regime: she endures and repulses a racial slight at the millinery shop (a potent reminder of black women’s treatment in downtown department stores during Jim Crow); a white saleswoman tries to make a sale in the black beauty shop and inadvertently says, “I worked like a nigger to earn these few pennies”; when Maud goes to work as a domestic during the Depression, her upper-class employer treats her like a child; at the World Playhouse, she and her husband Paul experience themselves as “the only colored people here”; on the campus of the University of Chicago, she encounters the elitism of university whites and blacks; and, finally, in that revered public spectacle of 1950s hegemonic whiteness—visiting Santa at the downtown department store—she finally recognizes and voices her stifled rage when the white Santa dismisses her little daughter. In what may seem only a minimal expression of her anger, she revokes his cultural title and authority: “Mister … my little girl is talking to you.” The entire city, from the downtown department store to the university campus, serves up ammunition for Maud’s racial critique, producing a militant rhetorical analogue to the black Left’s militant 1940s campaigns to “desegregate the metropolis.” If the culture of the Cold War was designed to produce smooth surfaces for U.S. consumption—images of domestic family tranquility with the woman’s place in home and family, good wars, and the harmony of racial integration, interracial cooperation, and black docility—

Maud Martha disrupts on every front.

BEYOND THE 1950S: THE LEFT IN THE BEAN EATERS

Brooks submitted the manuscript of

The Bean Eaters, her third volume of poetry, to Harpers in December 1958, and the editors “enthusiastically” accepted it for publication (Melhem 1987, 100). The black nationalist poet and critic Haki Madhubuti dismissed

The Bean Eaters in his 1966 essay on Brooks with one line, “

The Bean Eaters is to be the last book of this type,” inferring that Brooks’s subsequent poetry would mark the beginning of her political and racial consciousness. Brooks herself dubbed the book her “too social” volume because it had almost immediately been identified as “politically” charged—even “revolutionary,” and she had a hard time getting it reviewed (Madhubuti 2001, 87; Brooks 1983, 43). In fact, Brooks says that

The Bean Eaters was a “turning point ‘politically,’ its civil rights poems and its pointed critiques of class prejudice and racial violence so startlingly different from her earlier work that the reviewer for

Poetry wrote that it had too much of ‘a revolutionary tendency’ and was too ‘bitter’” (Brooks 1983, 43).

22 Brooks’s biographer Melhem notes that fully one-third of the thirty-five poems in

The Bean Eaters were “distinctly political” (1987, 102).

In view of the political directness of

The Bean Eaters, it is stunning that so many of Brooks’s critics insisted that she became “political” only after 1967 and that her poems from the 1940s and 1950s were apolitical and directed at a white audience. In

The Bean Eaters, written during the 1950s and published in 1960, Brooks initiates all the themes that critics associate with her black nationalist period. Moreover, she goes beyond the category of race to include issues of gender, class, and war. Brooks’s subjects in

The Bean Eaters are nearly always black and working class, and her relationship to these subjects compassionate, though, as always, Brooks’s use of an ironic, mocking voice makes it impossible to draw any easy conclusions about the aims of her critiques (Gery 1999, 44–56). Beyond that compassion is her determination to expose the way conventions of respectability, Christian norms, racism, and classism dominate and oppress working-class and racialized subjects. Her subjects in

The Bean Eaters are as follows: an elderly devoted couple eating their beans in “rented back rooms” and fingering the mementos that bespeak a life of poverty and lifelong faithfulness; the racial and class violence directed at a young couple who make love in alleys and stairways; the Chicago black working class drinking their beer in the establishments once an enclave for the rich; Emmett Till, “a blackish child / Of fourteen, with eyes too young to be dirty” and a mouth of “infant softness”; the pool players who live in urban ghettos, expecting short and brutal lives; the homemaker Mrs. Small, trying to manage breakfast for her six, an abusive husband, and the payment for the (white) insurance man; the “brownish” girls and boys of Little Rock, caught in a storm of race hatred from the white mothers; “those Lovers of the Poor” who “cross the Water in June,” “Winter in Palm Beach,” and cannot endure an actual encounter with the poor; the emptiness of middle-class consumption; Rudolph Reed dying in order to protect his family and home from white racial violence; and, finally, an antiwar poem that critiques the war aims of generals, diplomats, and war profiteers and assails the people’s desire for war. I list these subjects in some detail as further proof of the political, racial, and class issues Brooks took on in her 1950s work.

I conclude this chapter with a discussion of three poems in The Bean Eaters that bear the signs of Brooks’s leftist poetic sensibility, two of which make specific references to the Left. The first, entitled “Jack,” I assume to be about Brooks’s leftist radical friend Jack Conroy, and the other, “Leftist Orator in Washington Park / Pleasantly Punishes the Gropers,” the only poem in which she actually makes a direct reference to the Left. Almost nothing has been written about Brooks’s long-term friendship with Conroy, identified by the literary and cultural historian Alan Wald (2001, 269) as “pro-Communist” or a “fellow-traveler.” That friendship—both literary and personal—is established in the letters between the two written between 1945 and 1983. Conroy’s biographer Douglas Wixon says Brooks met Conroy at the South Side Community Art Center. Alice Browning, a student in Conroy’s writing class, asked for Conroy’s help when she started Negro Story, and Brooks was there at Browning’s house for meetings with Conroy (Wixon 1998b, 426n37). Conroy’s close relationships with and support of black writers are almost unprecedented. His friendship with the black writer Arna Bontemps spanned twenty years and produced several collaborative works, including the 1945 social history of black migration, They Seek a City, as well as several books for children. He seems to have been a ubiquitous presence and a beloved friend and colleague among black writers, including Bontemps, Browning, Frank Yerby, Willard Motley, Melvin Tolson, Frank Marshall Davis—and Brooks.

The letters between Brooks and Conroy begin in 1945, shortly after the publication of her first volume of poetry. In the first letter of September 14, 1945, which is mentioned above, Brooks confides in Conroy that she is pleased with “a very generous” review of

A Street in Bronzeville in

New Masses. Brooks’s greetings change from “Mr. Conroy” in the 1945 letter to “Jack” in subsequent letters, as their friendship deepens.

23 Wixon says that “Gwendolyn Brooks (among others) was a frequent guest at the parties given by Jack and Gladys on Green Street”(1998b, 462). In a letter from 1962, Conroy asks Brooks to autograph

Maud Martha and

A Street in Bronzeville and confides in Brooks about the troubles getting his books published because of his blacklisting:

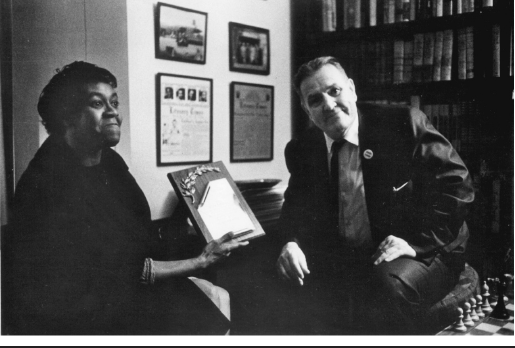

Source: Photo courtesy of Douglas Wixson.

The trouble is they [his books] were translated and published freely several years ago and I was never paid anything. In Russia they had a huge sale. Now I see the Russians are willing to pay American authors, and I have put Pfeffer on the trail of my lost rubles. Don’t know whether I ought to accept them or not, for McCarthy is not dead but only sleepeth. Besides, Eastland and Walters seem to have taken over where the Republicans left off.

24

In another letter remarking on Brooks “rusticating” at the writers’ retreat Yaddo, Conroy says he is going to look in on her husband Henry Blakeley while Brooks is gone.

25 Later in 1967, Brooks, by now a Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, presented Conroy with the first Literary Times Prize, praising him for “his aid and encouragement to young writers and his overall contribution to American literature, particularly his novel

The Disinherited” (Wixon 1998b, 482), which she called a “classic.” Brooks obviously felt an extraordinary sense of kinship with Conroy. She admired his devotion to the working class; his unpretentiousness; his wariness of ideology; his multicultural, multiracial friendships and collaborations; and his love of parties. While nothing in these archives proves that Brooks was a Party member or even that she could be considered on the Left in the 1940s or 1950s, this friendship, almost totally undocumented in any critical or biographical work and strangely unremarked on in Brooks’s own work, is further evidence that Brooks was no stranger to the Left.

Since the poem “Jack” appears to be about someone Brooks knew, and since it reflects qualities one might associate with Conroy, I read the poem as a description of Jack as a kind of secular saint. It opens with a typical Brooks irony, appearing at first to honor Jack in religious terms, calling him a man of “faith.” Knowing, of course, that Conroy was a Marxist, Brooks has revised “faith,” inserting instead an economic metaphor: he is not, the first line tells us, “a spendthrift of faith” but one who carefully doles out his faith with “a skinny eye,” waiting to see whether or not that faith is “bought true” or “bought false”:

And comes it up his faith bought true,

He spends a little more.

And comes it up his faith bought false,

It’s long gone from the store.

Not religious in any sense of a formal creed, this man’s “faith” is an ethic of integrity based on an ideal of justice whose results must be observable, not on the abstractions of traditional notions of “faith.” After Conroy’s death, Brooks took a trip to his hometown, Moberly, Missouri, where he moved in 1965 after leaving Chicago, to give a talk about him. Wixon discusses the visit in his biography of Conroy and says it clearly demonstrated Brooks’s close ties to her friend (1998, 482).

In addition to this poem dedicated to an openly leftist radical, Brooks’s Left-inflected “Leftist Orator in Washington Park / Pleasantly Punishes the Gropers,” suggests her familiarity with scenes in Washington Square Park, where militantly black and Left soapbox orators regularly spoke. As a result of the demographic changes following World War I, when African Americans moved into the area, Washington Square Park became a site of racial tension and conflict in the 1920s and 1930s, and by the late 1950s, the park had become the (un)official dividing line between the black South Side and white Hyde Park (Brooks 1983, 41). Bill Mullen notes that Washington Square Park, bordering the Black Belt, had a long reputation as the “South Side’s public flashpoint for speeches and demonstrations by black Garveyites, Communists, unionists, and other radicals,” (Mullen 1999, 67), and, in the early 1930s, it attracted thousands of blacks to hear its political speakers, even some black women speakers.

26 According to the cultural historian Brian Dolinar, in the late 1950s, when Brooks was writing

The Bean Eaters poems, the park would have attracted a mostly black audience.

27 There are stories of large Garvey parades in Washington Park, and the black historian Hammurabi Robb gave soapbox oratories there.

28 Brooks might have known the park as a black cultural site because it is specifically named in Richard Wright’s novel

Native Son, when Bigger Thomas drives the drunken Jan Erlone and Mary Dalton around Washington Park as part of their desire to experience black space. As Jan and Mary embrace, Bigger “pulled the car slowly round and round the long gradual curves” and drove out of the park and headed north on Cottage Grove.

29In Brooks’s poem, the leftist orator acknowledges that he or she is engaged in a thankless and hopeless task, trying to fire up the audience in this “crazy snow,” an audience that is rushing to get out of the cold, fearfully aware that “the wind will not falter at any time in the / night.” At the beginning of the poem, the speaker is compassionate toward these listeners, the “Poor Pale-eyed” (not “Pale-skinned), knowing that they “know not where to go.” Aware of his (or her) own ineffectiveness, the orator seems resigned to the reality that he cannot offer enough inspiration to compete with the wintry weather or reach this audience of “gropers” with a vision capable of stirring them. Speaking in the voice of a religious prophet, however, he blames their indifference on more than simply a need to get in out of the cold, but also on a failure of vision: “I foretell the heat and yawn of eye and the drop of the / mouth, and the screech / Because you had no dream or belief or reach.” While the poet understands these “gropers,” like the folks in Brooks’s “kitchenette building,” as people under the harsh and insistent material realities of their lives, the speaker’s sympathy is for the leftist orator, who is committed to remaining out in the cold trying to reach the people, and perhaps she even shares the orator’s desire to punish them “pleasantly” for their obstinacy. Even if the “thrice-gulping Amazed” listeners are not entirely indifferent to the speaker’s message, the pattern of threes in the poem (“thrice-gulping”; “the heat and yawn of eye,” “the drop of mouth,” and “the screech”; “no dream or belief or reach”; “were nothing,” “saw nothing,” “did nothing”) points perhaps to the three denials of Christ by Peter and a harsher rebuke of the crowd as not only indifferent and preoccupied but also as betrayers of themselves and of a larger cause. As the orator tries to reach a reluctant and indifferent audience, it is striking to note that the narrator’s sympathy is evoked for both the unheeding crowd and the determined but ineffectual “leftist orator.”

30We can only speculate about what is actually said by the leftist orator, the “I” of the poem, in his address to the Washington Park crowd, since his actual speech is unnarrated, but he speaks in several registers that would appeal to a black audience—as a political voice, as the voice of a religious prophet, and as the poetic voice. In her reading of the poem, Brooks’s biographer D. H. Melhem assumes that the audience is white and that the orator is castigating them for their apathy and lack of conviction (1987, 118). But in the late 1950s, the park would have been a predominantly black or interracial gathering center and that audience almost certainly not entirely white.

31 Moreover, Brooks deliberately employs

whiteness to refer to the weather and thus anticipates then forestalls any easy identification with race. In Brooks’s critique, the “Pale-eyed” listeners seduced into indifference and complacency and unwilling to act, is a recurring theme in her poetry and not necessarily racially inflected.

32Two more poems from The Bean Eaters I read as representative of a “Left” political sensibility because they show Brooks’s profound alignment with those disadvantaged by class and race. The first poem, entitled with Brooksian irony “A Lovely Love,” is about the first sexual experience of two young people whose lives are such that the encounter takes place in an alley or stairway. The poem opens with an imperative: “Let it be alleys. Let it be a hall … Let it be stairways and a splintery box.” Rather than the imaginative space of the conventional sonnet where love is accorded dignity and meaning, the space these lovers occupy for their illicit love creates a disturbance: it is a place that “cheapen[s] hyacinth darkness,” where there is “rot” and “the petals fall.”

The elegiac mood and bitter wisdom of the poem are created by the speaker addressing her or his lover, speaking of the way their love affair is cheapened not by their lovemaking but by ugly “epithet and thought” thrown by those “janitor javelins” that “rot” and “make petals fall.” As she has done repeatedly throughout this period of her “high” modernist experimentation, Brooks revises a high modernist form—the sonnet—to critique those traditions and to give to the poor the trappings of poetic form.

The speaker, however, is resistant to the defamation of her experience, and to honor that experience, she (or he) endows it with the elegance and fragrance of “hyacinth” (the “hyacinth darkness that we sought”). The speaker, small enough to be “thrown” down, then “scraped” by her or his lover’s kiss and “honed” as one would sharpen a tool, is not caressed in this encounter. Nonetheless, the act entails more than the awkward and inadequate moves of a young lover; he or she smiles away their “shocks” in an attempt to be reassuring, and the poem shows that both these inexperienced young people have been unsettled by their sexuality. In the third quatrain, the speaker compares this love and the possible birth it might produce to the birth of Christ and, in a caustic comparison, names Christ’s birth “that Other one,” charging religious myth with both irrelevance and otherness: this Cavern is not the mythic cave of the Christ child, and there are no “swaddling clothes,” no “wise men,” and no blessed birth. The birthright of the lovers is only the feeling that they must run before they are caught, probably by those people whose “strict” rules, both religious doctrine and social norms, would condemn their lovemaking in alleys and stairways: “Run / People are coming. / They must not catch us here / Definitionless in this strict atmosphere.”

There is another reference in the couplet to the strict conventions of the sonnet form. By its repeated references to those public, dark, and indecent locales, the poem, like the couple, violates the lovelier love traditionally associated with the sonnet. In this space outside of conventions, the couple is “definitionless,” without standards or traditions reserved for those “lovelier loves” sanctioned by myth, convention, and poetic traditions. So, what to make of the title, “A Lovely Love,” and the opening tag “Lillian’s” beneath the title of the poem? Is this poem a tribute to someone named Lillian and to Lillian’s “lovely love,” perhaps her first sexual experience? Brooks is, of course, subverting the traditions that have historically omitted girls (and boys) like these two.

In a conversation with the literary critic Aaron Lecklider, I became aware of the gender ambiguity of the poem. Since the only gender signifier is the reference to “Lillian’s” that prefaces the poem—the poem invites a queer reading, with the two young lovers possibly a same-sex couple. Under the terms of a homophobic culture, two gay lovers would also be labeled “Definitionless.” This lexicon of deviance and transgressiveness in the poem suggests that in pushing against the boundaries of respectability Brooks may have intended to align the poem with sexual as well as class deviance in the narrator’s embrace of the two lovers. I would argue that a queer reading of the poem is further evidence that Brooks was clearly capable of the political

deviance, boldness, and indifference to conventional norms required for an embrace of the Left.

33“The Ghost at the Quincy Club” is a companion poem to “A Lovely Love,” with Brooks again taking on the issue of class and the “dark folk” omitted from, marginalized by, and discarded by white patriarchal traditions. The Quincy Club is an old upper-class establishment, a genteel social club of “Tea” and “Fathers,” owned and dominated by the white male elite that excluded black and Jewish folk, where the African American DuSable Museum is now located. The poem opens with a vision of the past, with one of the genteel (“Gentile”) daughters of the former Quincy Club fathers drifting down the staircase and wafting into the halls of “polished panels” in their “filmy stuffs and all.”

The poet-narrator is blunt and sarcastic, sneering at these “Gentile” daughters turned, presumably by their fathers, into “filmy downs,” “filmy stuff,” “Moth-soft” and “off-sweet”—ephemeral, insubstantial, and easily snuffed out. Their “velvet voices” are described here as moving almost as though directed by a metronome (“lessened, stopped, rose”)—that imposes on them an exact and precise rhythm. The enjambment between the first and second line in this stanza forces the “velvet voices” to give way to the “Rise” of the “raucous Howdys,” those new raw sounds that now, with energy and swagger, perhaps with vulgar curse, challenge and replace the old, the privileged, and the white. In the current arrangement of things, “Tea and Father” are replaced by “dark folk, drinking beer.”