Garrison Duty in New Brunswick, the War of 1812, and the March to Kingston

In all respects fit for any service.

— Inspection Report, 104th Foot, June 1812

The King’s New Brunswick Regiment, The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry, and the Formation of the 104th Foot

During the eighteenth century, a series of conflicts shaped the early political boundaries of North America. By 1783, three major political groupings had emerged: Britain held colonies in the northeast; to the south were the United States of America; and to the west, the colonial holdings of Spain. A commercial company, the Hudson’s Bay Company, controlled a vast tract of land in the northwest. The First Nations peoples inhabiting these territories did not always recognize these boundaries, which remained ill-defined for nearly a century. Ongoing competition between the respective governments for additional territory and fears for their own security soon combined with wider political differences in Europe to ensure another war in the early nineteenth century.

Even with the loss of thirteen of its North American colonies in 1783, Britain’s colonial possessions in the New World remained vast, with the largest group of colonies becoming known collectively as British North America: the provinces of Quebec and Nova Scotia, the Island of Cape Breton, the Island of St. John (later, Prince Edward Island), and Bermuda; the Colony of Newfoundland was not included in this structure. The displacement of a large number of refugees from the United States, popularly known as Loyalists but also including a significant number of First Nations peoples, to the remaining British colonies and to Britain transformed the boundaries of British North America. In 1784, the province of Nova Scotia was partitioned and the province of New Brunswick created, while in 1791, the province of Quebec was divided into the largely English-speaking province of Upper Canada and the predominantly French-speaking Catholic province of Lower Canada.

In general terms, peaceful relations dominated the years immediately following the American Revolutionary War. The most serious threat occurred on the west coast, where, in 1789, the establishment of a Spanish outpost at Nootka, on Vancouver Island, nearly led to war between Spain and Britain. The peaceful conclusion of this crisis by treaty in 1790 was followed four years later by a reduction in tensions with the United States. The Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation, more popularly known as Jay’s Treaty — after the senior American negotiator, John Jay — resolved many of the boundary disputes between the United States and the British colonies to the north. Despite the rapprochement, however, mutual suspicion remained, and the ongoing war between the United States and First Nations groups in Ohio and the Michigan and Illinois Territories had the potential to spill over into Upper Canada.1

These events, however, were minor against the backdrop of a wider global war that erupted in 1793, when Britain joined a coalition of several European countries to oppose revolutionary France. As France defeated its opponents on the continent, Britain’s command of the sea allowed it to secure several important victories in the Mediterranean and the West Indies.2

The perceived threat to the Atlantic provinces from both France and Spain fuelled public support and saw a swelling of willing recruits for military service. In July 1793, a French naval squadron with 2,400 troops arrived off New York, where they began recruiting Americans and seeking the support of the United States for an attack on the British Atlantic colonies. The threat posed by the French using Saint-Pierre and Miquelon as naval bases to strike at the Atlantic provinces was removed in May 1794 when a contingent of four hundred British soldiers and members of the Nova Scotia Regiment took the islands. The appearance of a combined Franco-Spanish squadron of twenty vessels carrying 1,500 troops off Newfoundland intensified the completion of defensive works, while a landing by the enemy at Bay Bulls resulted in little more than looting by French soldiers.3

Although the British relied upon regular troops to defend their North American provinces, the active theatres in Europe and the West Indies left few such troops available for service elsewhere. The colonial militia forces, raised from among all able-bodied men ages sixteen to sixty and controlled by each province, were inadequately trained, and lacked much of the necessary arms and equipment to be useful in the field. The fortifications protecting key points, such as cities and harbours, were in a poor state or lacked ordnance.4

The military situation in New Brunswick was acute. Since 1790, Governor Thomas Carleton had warned of the exposed state of the communities along the Bay of Fundy, the ruinous state of the fortifications, and the lack of arms. The impending withdrawal of the last British regulars from the province would leave the militia responsible for repelling any attack. Unfortunately, little had been done to prepare the force created by the 1787 militia act. Many companies and regiments lacked a full complement of men, and many of the officers owed their appointments to political patronage, rather than to martial skill. Musters were dominated by administrative activity and social events, and the lack of weaponry provided few opportunities for effective drill instruction. Fortunately, by 1791, British officials had presented a solution for improving the state of the garrisons throughout British North America with the creation of fencible and provincial regiments.5

Although they had ancient precedents, fencible regiments originated during the Seven Years’ War when Britain established several such regiments to defend itself from invasion. Equipped, trained, disciplined, and paid as regulars, fencible infantry and cavalry regiments were raised with the understanding that their deployment would be restricted to within national boundaries or other specified geographic areas, such as a county, and that their service could be extended abroad only by their volunteering for this service. When the war with France began in 1793, Britain accordingly expanded its regular Army for employment overseas, while fencible units augmented the militia in England, Scotland, and Ireland. This system was extended to North America, where the formation of a number of regiments of fencible infantry would release the regular regiments garrisoned there for employment elsewhere.6

Beginning in 1791, fencible regiments were raised in several provinces of British North America. Among the units were the Queen’s Rangers in Upper Canada, the Royal Nova Scotia Regiment, the Island of St. John’s Volunteers (from 1800, the Prince Edward Island Fencibles), and the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. In 1794, the two-battalion Royal Canadian Volunteers was divided between Upper Canada and Lower Canada.

Provincial regiments presented another means of augmenting local forces. Normally raised for the duration of a conflict, they were officered by professional officers, dressed, equipped, and trained like regulars, and employed in a specified geographic area, although they often ventured outside their boundaries. The appeal of this type of unit was that it provided a solution to a local problem by bolstering the defences vacated by regular troops, at less cost than a regular regiment. The specifics regarding officers’ commissions, the pay and benefits to officers and the rank and file, employment of the regiment, and command and control varied with the orders provided for the raising of each provincial unit.

In February 1793, given the state of New Brunswick’s defences, the Secretary of State for War, Henry Dundas, instructed Governor Carleton to raise a six-hundred-strong unit to be known as The King’s New Brunswick Regiment. The regiment was to be headquartered in Fredericton, and the posting of six of its companies to Fredericton, Saint John, and St. Andrews would allow the withdrawal of the 6th Foot, the last regular regiment in the province, for employment in the West Indies. Carleton, who welcomed this decision and became colonel of the regiment, controlled the officer appointments. All officers above the rank of ensign were selected from a list of half-pay officers or were veterans of the American Revolutionary War. As the regiment was “merely provincial and for the service of New Brunswick only,”7 the officers’ commissions provided them with local rank, as they were not granted regular Army commissions. Despite its provincial status, which normally meant it fell under the provincial militia structure, The King’s New Brunswick Regiment was subject “to the Control and Orders of the Commander in Chief of His Majesty’s Forces in North America or to such other orders as in His Majesty’s wisdom he may think proper to give.”8 Lieutenant-Colonel Beverly Robinson, who was born in the colony of New York and served, along with his father, in the Loyal American Regiment during the American Revolutionary War before relocating to British North America, was appointed commanding officer.9

Not everyone shared Carleton’s enthusiasm for the formation of this regiment, and one member of the provincial assembly questioned whether the removal of “one fifth of the population capable of bearing arms and at least one-third of the more active young men”10 would benefit the province. There might have been some truth in this, as recruiting in Fredericton and Saint John, the settlements bordering the St. John River, and at St. Andrews, on the frontier of the province, progressed slowly. By July 1794, only three hundred of the four hundred and fifty men on the roll were considered effective, and the number was well below the establishment of six hundred. 11 Despite these difficulties, the regiment was immediately put to work improving defensive works and roads. This activity was interrupted by occasional alarms, caused by reports or, more often, rumours of the presence of French naval forces or landings on the Fundy shore, none of which amounted to anything. By the end of the decade, the threat of invasion had subsided, and interest in defence matters in the province declined.

By 1802, as French successes on the European continent left Britain without allies and facing a strong threat from Napoleon’s forces, the two countries entered into a peace agreement known as the Treaty of Amiens. Peace was welcomed, and through the summer and autumn of 1802, all the fencible and provincial regiments in North America were disbanded. Confronted more by scares than by actual threats, these units nevertheless had created a firm basis for the defence of the colonies, and demonstrated that British North Americans could serve alongside British regulars effectively. The detachments of The King’s New Brunswick Regiment serving outside Fredericton were recalled, and in August 1802 the regiment was disbanded. In consideration of their service, the officers were placed on half-pay and the men received grants of land.12

The peace was short lived, however, and within fourteen months war was renewed, requiring the resumption of improvements to the defences of British North America. As the regular garrison would not be returned to its previous strength, the British government ordered the raising of four fencible regiments of infantry: The Canadian Fencibles in Lower Canada, the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles, the Nova Scotia Fencibles, and The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry. For now, no regiment was to be formed in Upper Canada.13

In June 1803, Brigadier-General Martin Hunter (the following year he was promoted to major-general) was appointed colonel of The New Brunswick Fencibles, the titular head of the regiment who oversaw its institutional well-being, which included advising the commanding officer on regimental matters, including officer appointments. On paper, the organization of The New Brunswick Fencibles14 was similar to that of a British line regiment according to the “new” establishment that had been introduced in 1804: with 1,123 officers, NCOs, and rank and file distributed among a twelve-man headquarters, eight “centre” or “line” companies of 111 officers, NCOs, and men each, and two “flank” companies, one of grenadiers with 112 all ranks, and the other, a 110-man strong “light” company. Each line company consisted of a captain commanding, two lieutenants, one ensign, five sergeants, five corporals, two drummers, and ninety-five privates. The flank companies had a similar structure, although an additional lieutenant was provided in lieu of an ensign, and the grenadier company had fifers instead of drummers. (More will be said of the differences between the line and flank companies later.) There was no allowance for a paymaster or pay sergeants.

Lieutenant-General Sir Martin Hunter was instrumental in raising The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry and its subsequent transfer to the line in 1810 as the 104th Foot. He also served as the colonel of both regiments. Courtesy of Martin Bates and NBM X15765(2)

Instead of a commissioned assistant surgeon, at first two senior non-commissioned surgeon’s mates saw to the unit’s medical needs.15 In 1807, however, William Dyer Thomas, an experienced surgeon who had commenced his career in 1800 with the 1st Dragoon Guards, was appointed to The New Brunswick Fencibles. The surgeon’s duties included the administration of the regimental hospital, the care of the sick, and the treatment of battlefield casualties. In contrast to physicians, who held high academic qualifications, surgeons had a more modest education, although they generally possessed a university degree (or at least proof of attending medical lectures and experience in a practice), a licence from the College of Surgeons, and had successfully completed an examination by the Medical Board. Assistant surgeons had some education, and were required to pass an exam set by the surgeon. Surgeons were ranked as, but not equivalent to, captains and their assistants as lieutenants.16 Requirements concerning medical appointments varied during the Napoleonic Wars, but by the time William Thomas became surgeon, controls had become stricter and, aside from the recommendation of his commanding officer, his appointment required approval by the Medical Board. Thomas later served with the 104th Foot until he went on half-pay in 1816.

One of the two assistant surgeons was Thomas Emerson. His military service began during the American Revolutionary War, when he joined the Royal Fencible Americans, after which he was granted land in Nova Scotia. In 1793, he became surgeon’s mate (the title was changed to assistant surgeon in 1796) in The King’s New Brunswick Regiment. Then, in August 1804, he signed up as assistant surgeon with The New Brunswick Fencibles. Another assistant surgeon was Charles Earle, who served until January 1812, when he went on half-pay. Earle was replaced by William Woodford until May 1814, when Woodford transferred to the newly formed New Brunswick Regiment of Fencible Infantry, although he remained with the 104th until the summer of 1814.17

The unit establishment made no mention of pioneers — soldiers who were given special equipment and some training to build or clear minor obstacles, clear routes, and do other heavy work. According to the Army Regulations, however, “no regiment is considered fit for service unless the Pioneers are completely equipped.”18 The Regulations specified that one corporal and ten privates (one per company) were to be appointed as pioneers, and the colonel of a regiment was responsible for their having “Tools and Appointments [equipment] . . . in a complete and serviceable state.”19 Special equipment included one apron per man and their tools included bill-hooks, spades, picks, felling and broad axes, saws, and mattocks.

Many pioneers were black.20 The British services increased the available source of manpower through the recruitment of blacks in Africa, the West Indies, and North America. These men served in line regiments, colonial corps, specially recruited regiments from the West Indies, a regular corps of pioneers and artificers, and in the Royal Navy and the Royal Marines. In 1814, the Corps of Colonial Marines was formed in the West Indies from runaway American slaves. The “Company of Coloured Men” was raised in Upper Canada at the outset of the War of 1812, and in October 1812, it fought at the Battle of Queenston Heights. A number of blacks also joined the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles, although their number is difficult to establish as the records make no distinction by race. Sixteen blacks are said to have joined The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry as pioneers, many of whom later served in the 104th Foot. One man, Henry Grant, who joined The New Brunswick Fencibles in 1808, eventually became a bass drummer in the regimental band.21

The eighteen drummers and two fife players in the battalion should not be confused with musicians or the “band of music.”22 The drummers and fifers played an integral role in the internal regulation of the companies, for which they received extra pay and allowances. The drummers’ uniforms were more lavish than those of the fifers and, later, buglers, who were dressed like the rest of the men in the regiment. General Regulations also permitted the colonel to form a band, consisting of one private per company plus a sergeant as bandmaster. All of these men “were to be Effective to the Service as Soldiers, are to be perfectly drilled, and liable to serve in the Ranks on any emergency.”23 Although a band was not authorized upon The Fencibles’ establishment, one appears to have been formed shortly afterward, and included the company drummers and fifers and a number of musicians who played other instruments. An 1810 inspection report indicates that bugles had replaced the drums in each company, although by 1813, when the 104th Foot was preparing to march to Canada, it was reported to have both drummers and buglers.24

As was the practice with the other fencible regiments raised in British North America, The New Brunswick Fencibles were allowed to recruit in “any part of the British colonies in America.”25 Recruiting parties accordingly ventured throughout New Brunswick and into Lower Canada, and Nova Scotia, and enjoyed some success in attracting colonists to the colours. The story was different in Newfoundland, where Governor Vice-Admiral Sir Erasmus Gower ordered the recruiting parties, for reasons unknown, to leave the colony. Authority was also granted to recruit in Scotland, and the recruiting parties there extended their reach into Ireland. Experienced NCOs and men also came from other regular regiments, such as the 37th and 60th Regiments of Foot.26

The standards for recruitment specified that enlistment was to be voluntary and open to all “stout and well made”27 males over five feet five inches in height and, ideally, between seventeen and thirty years of age. As an inducement to join The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry, each recruit would receive a bounty of six guineas, a sizable sum, which would be paid in increments following examination by a surgeon, attestation, and inspection by a senior officer.28 They would also receive up to five hundred acres of land when the regiment was reduced. The Fencibles were also allowed to recruit boys and lads who were “perfectly well limbed, open chested, and what is commonly called long in the fork [long legged],”29 not less than five feet tall and aged between ten to fifteen years of age. The recruitment of boys was always strictly controlled, as they were an extraordinary source of manpower and could be employed only on general duties or as drummers, until they became seventeen, when they could carry arms and be employed in the infantry as privates. Many learned to read and write in regimental schools, which groomed them for future appointments as NCOs. Many of the boys were related to soldiers serving in the regiment.30

To find additional men, Hunter sent Major John White “out to Canada on the Recruiting Service.”31 White was given additional authority to recommend six suitable gentlemen for appointment to the rank of captain, lieutenant, and ensign. Operating from Montreal and Quebec, White succeeded in recruiting a number of men, whom he dressed in uniforms found in Montreal for the 60th Foot, which was currently stationed in England and not expected to return to Canada. White died in March 1804, and Captain Thomas Christian was appointed commander of the recruiting effort in the Canadas, while Captain Dugald Campbell took command of the recruits at Quebec, assisted by Captain A. Sutherland. Earlier in the year, to get to Quebec, Campbell had completed an arduous journey from New Brunswick overland on snowshoes. Additional recruiting parties commanded by Lieutenants René-Léonard Besserer and David Miller were sent further inland to Kingston and York (later Toronto), respectively.32

By April 1805, 121 recruits had been collected at York, Kingston, Montreal, and Quebec, although difficulties then arose in approving their enlistment. A proposal put forward by Captain Christian to have Lieutenant-General Peter Hunter, the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, inspect the men, which would confirm them as being suitable recruits before they were sent to New Brunswick, was refused, as Hunter claimed he lacked the authority to do so. At Fredericton, Major-General Martin Hunter then petitioned London for approval, which was granted later that year, albeit after the recruits in the Canadas had marched overland from Quebec to New Brunswick. Recruiting continued in the Canadas until the spring of 1808, when it was ordered halted by Sir James Craig, the commander-in-chief and governor of British North America.33

An officer’s coatee from The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry. The coatee is scarlet with light buff colour cuffs, lapels, and turnbacks, with silver buttons. Courtesy of the Fredericton Region Museum 1969.2547.1

Unlike the broad conditions permitted for the recruitment of the rank and file, the Horse Guards, the headquarters of the British Army in London, closely regulated the appointment of officers. Thus, unlike The King’s New Brunswick Regiment, the officers assigned to The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry received permanent rank in the Army, and would be eligible for half-pay once the regiment was reduced. Over three quarters of the officers appointed to the regiment already held regular commissions, including the commanding officer, both majors, and all of the captains. Many of the subalterns — the ensigns and lieutenants — also came from regular regiments and a number were newly appointed, including a few who were recruited locally.34

Major George Johnston of the 29th Foot was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and placed in command of The New Brunswick Fencibles. Since they were currently in Scotland, Johnston and several of the recently appointed officers decided to remain there and see to recruiting soldiers. Other officers came from the 46th Foot, the 11th West India Regiment, and the Cape Regiment; most of them were on active service, while a few were on half-pay. As was the custom at the time, two important officer appointments were made from NCOs. Sergeant Major Edward Holland of the 40th Foot was appointed an ensign and made adjutant; in 1812, he was promoted captain and given command of a company. Sergeant James Hinckes of the 43rd Foot became the quartermaster, in charge of regimental equipment, forage (for the horses), and rations.35

When, in January 1806, Lieutenant-Colonel Isaac Tinling, the deputy quartermaster general at Halifax, inspected The New Brunswick Fencibles at Fredericton, he found the regiment in good order and discipline, and rejected as unsuitable for service only a few of the 692 officers, NCOs, and men on parade. This figure was an important milestone, since a minimum of five hundred rank and file had to pass inspection — meaning they had to receive a senior officer’s final approval that they were fit for service — before the regiment could be placed on the Army’s official establishment. The King responded favourably to Tinling’s report, and ordered The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry to be placed “on the regular establishment of the army as of 25th June 1805.”36

Not long afterward, the regiment commenced its duties, although recruiting efforts continued in order to bring the regiment to its authorized strength of a thousand men. From its base in Fredericton, the regiment was distributed among garrison outposts on the Fundy Shore. In September 1807, a company was posted to Saint John and another divided between Saint John and St. Andrews, and in early 1808, four companies were sent to Saint John. In June, No. 1 Company was sent to Sydney, Nova Scotia, and No. 4 Company to Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. Both would remain in those locations for the next two years.37

On January 1, 1806, at a ceremony held in Fredericton, Major-General Hunter presented The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry with a set of Colours. The stand of Regimental Colours included two flags, the King’s Colour and the Regimental Colour. Both were made of silk and measured six feet six inches in the fly and six inches on the pike. Each was carried on a pike nine feet six inches long, including a four-inch spearhead. Atop of each pike were two three-foot-long silk cords and tassels. The King’s Colour was the Union Flag, while the field of the Regimental Colour was the same as the unit’s facing Colour, with the cross of St. George and a small Union Flag in the canton. The regimental name appeared in the centre of each Colour, surrounded by a wreath of roses, thistles, and shamrocks. Unfortunately, the true appearance of the stand of Colours belonging to The Fencibles will never be known, as they have disappeared, although there is speculation that they were modified when the regiment became the 104th Foot; these later Colours are displayed at the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John.38

In June 1807, Anglo-American relations underwent a serious reverse following the Chesapeake-Leopard incident, in which the British frigate HMS Leopard intercepted, fired on, and then boarded an American warship off the coast of Virginia. As Britain and the United States appeared to be on the point of war, in late 1807 British authorities decided, in response to the poor state of Nova Scotia’s defences, to combine under a single person the head of the civil government and commander of the forces in that province. This was part of a wider trend that saw the colonial administration in British North America becoming increasingly military in character. In August 1807, Lieutenant-General Sir James Craig was appointed captain-general and governor-in-chief of British North America. Subsequently, in January 1808, Major-General Sir George Prevost succeeded the aging Sir John Wentworth as governor and commander of the forces in the Maritime provinces with the local rank of lieutenant-general.

Garrison duty, in light of growing tensions with the United States, did little to satisfy the desire of the officers and many of the men of The New Brunswick Fencibles to see action. In 1808, an opportunity presented itself when it was learned that Prevost was to command a division preparing to take the French-held island of Martinique in the West Indies. A brigade of regulars would accompany Prevost as a show of strength against the Americans.39 In November, after discovering a contingent was being readied to embark from Halifax, The Fencibles’ officers requested Major-General Hunter to forward their petition to join the Prevost expedition. The offer was forwarded to Governor Craig at Quebec, but no reply had been received when Prevost sailed with the brigade of regulars on December 6, 1808, bound for Jamaica.

When he arrived in Nova Scotia with three battalions of infantry in 1808, Prevost had distributed the regulars and fencibles among New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, and Prince Edward Island to counter the potential threat from the Americans. Over the next two years, however, as the crisis with the Americans appeared to diffuse, four of the regular battalions were transferred elsewhere. The reductions commenced in July 1809, when the 101st Foot, which had arrived in Halifax in 1807, departed for Jamaica. In June 1810, the 1/7th Foot left Nova Scotia for Portugal, followed by the 1/23rd in October. In August 1811, Prevost departed Halifax to take up the post of captain-general and governor-in-chief of British North America, and Lieutenant-General Sir John Sherbrooke replaced him as governor of Nova Scotia and commander of the forces in the Maritime provinces.40

In the meantime, trade continued to dominate the political differences between Britain and the United States. In May 1810, the US Congress had replaced the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, which forbade American trade with Britain and France and their colonies and which proved impossible to enforce, with Macon’s Bill No. 2 — named after the chairman of a congressional committee — and restored trade between the United States and Britain. Then, in August 1810, France promised to withdraw its trade restrictions on the United States if that country re-imposed non-intercourse with Britain. In November, the United States announced it would comply with Napoleon’s terms and issue a revised Non-Intercourse Act in the new year, although the French then reneged on their promise. The British responded by declaring that the re-imposition of non-intercourse was unjustified, and threatened to embargo American trade through Orders-in-Council unless US President James Madison provided proof that the French decrees had been lifted. This demand placed Madison in a difficult situation, as any response would have amounted to an admission that he had been tricked by Napoleon. Furthermore, it became clear to Madison that, until Napoleon was defeated, the Orders-in-Council would remain in force, which was an unacceptable condition. In July 1811, Madison chose instead to call the Congress into an early session in November, which “amounted to no less than a decision to prepare the United States for war with Great Britain.”41

British military leaders in the Maritime provinces faced a difficult situation. The success of the show of force by the arrival of a brigade of regulars had been illusory. The backbone of the local defences provided by the regular garrison had been weakened with the departure of four regular battalions, and although the shortfall was partially overcome with improvements to the militia forces of each province, more regular troops were required. Undaunted by their failure to accompany the expedition to Martinique, the officers of The New Brunswick Fencibles made a second offer to Governor Craig to extend the regiment’s sphere of service and become a regiment of the line, but that offer, too, was refused. The regiment tried again the following year, this time under the leadership of Major Charles McCarthy, acting since December 1809 in place of Lieutenant-Colonel Johnston, who was on a leave of absence in England. Again, The Fencibles’ officers sent their request to Major-General Hunter, but this time Hunter chose not to communicate with Craig, perhaps since he was aware that the governor was ill. Instead, he forwarded the application, with his endorsement, to the adjutant general at the Horse Guards in London, where it was to be laid “before the Commander in Chief for his favourable Consideration.”42 This time, the application was successful, and within weeks a Royal Warrant was issued for The “New Brunswick Fencibles being made a Regiment of Line and numbered the 104th Foot.”43

Into the Line: The 104th Regiment of Foot, 1810-1813

British policy prior to the beginning of the war with France in 1793 had been to augment the Army by raising new regiments, rather than by expanding existing ones. During the war, the number of regiments rose to 135, the majority of which were disbanded following the peace of 1802. In reforming the system, the Duke of York, the commander-in-chief of the Army, chose to abandon the practice of creating new regiments and instead increased the Army’s establishment by adding additional battalions to the existing 96 infantry regiments. The added flexibility of this new system allowed manpower to be used where it was needed. The mass of men serving in militia, volunteer, and fencible units was done away with, and newly raised battalions could be used for home defence duties or employed as a “disposable force” anywhere in the world.44

Accordingly, between 1807 and 1815, only three new regiments were added to the establishment of the Army. This was achieved by drafting two unnumbered colonial regiments and a reserve battalion into the line, rather than drafting them into other regiments. The 102nd was raised from the New South Wales Corps, the 103rd was created from the 9th Garrison Battalion, and The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry became the 104th Regiment of Foot.45

The establishment, or personnel strength, of a regiment included a number of fixed and variable elements that set the number of the rank and file at between eight hundred and twelve hundred men. Factors influencing which establishment a unit received included whether it had more than one battalion, and if it was to be garrisoned at home — meaning Britain or Ireland — or overseas, or deployed on field operations. Regular battalions normally consisted of a headquarters, eight line companies, each of the same strength, and two flank companies with minor differences in strength. When a single-battalion regiment or all of the battalions of a regiment went overseas, a recruiting company for each battalion was authorized to remain behind.46

Once taken into the line, the 104th Foot was placed on an establishment of eight hundred men, which was increased in November 1812 to one thousand rank and file. Its eight line companies were each commanded by a captain, assisted by one lieutenant, an ensign, four sergeants, and four corporals. In each company, eighty men filled out the ranks for a total, including two drummers, of 89 men. More specialized roles went to the grenadier and light companies, each with a similar number of officers, NCOs, and men as the line companies. The tallest and most experienced men went to the grenadier company, which the commanding officer employed as a shock or assault force. The light company — or “Light Bobs,” as they were nicknamed — acted as skirmishers, deploying around the regiment in extended order as an advance, flank, or rear guard, to cover the main body as it manoeuvred. The flank companies enjoyed greater independence from the line companies and, on campaign, it was common for them to be detached and employed separately. Finally, the regimental headquarters included a colonel — an honorary appointment almost always bestowed upon a general officer who never served with the regiment — a lieutenant-colonel as the commanding officer, two majors who commanded larger detachments or wings of the regiment in the field, a paymaster, an adjutant, a quartermaster, a surgeon and his two mates, the regimental sergeant major, a paymaster sergeant, a quartermaster sergeant, and an armourer sergeant.47

A plate of the 104th Foot as worn by an enlisted man on the 1812 pattern shako. New Brunswick Museum R2009.1

Those officers of The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry who held temporary commissions and were selected for the 104th now received regular Army commissions. Thus, the commission for Charles Rankin, who held temporary rank as a lieutenant, had seniority in the Army from November 1, 1811. Currently serving officers, such as Ensign Henry Moorsom, of the 24th Foot, or young gentlemen such as John Le Couteur, who held an approved application for a commission, also joined the 104th. Another notable officer, William Drummond, a Scot and a veteran with fourteen years’ service in the West Indies, had transferred in 1809 from the 60th Foot to The New Brunswick Fencibles. Whatever plans Drummond might have had for retirement at the time ended in 1810 when, following the departure of Major McCarthy to join the Royal African Corps, he accepted appointment as senior major of the 104th.48

Appointed as the first commanding officer of the 104th was Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Halkett. He had joined the 23rd Foot as an ensign in 1790 and in 1800, following a period in the West Indies and England, obtained a lieutenant-colonelcy in the 93rd Foot, which, in a situation similar to the 104th Foot, had been taken into the line from the Sutherland Fencibles. The regiment remained in Britain and Ireland until 1805, when it embarked for the Cape of Good Hope, where it remained in a state of inactivity until 1814, when it was transferred to the Gulf Coast of the United States.49 Halkett seems to have made little impression during his command of the 93rd, and his appointment as commanding officer of the 104th might have resulted from his previous experience in taking a fencible regiment into the line. Halkett was well known for his enjoyment of a drink; one member of New Brunswick society described him in 1811 as “very much given to drink and appears to want common understanding, but is of a good family.”50 Halkett also appeared to have encouraged “the natural taste for drinking in others.”51 A harsher view was offered by Captain Jacques Viger of the Voltigeurs Canadiens, who in 1813 described Halkett as an “indolent man, mellowed by wine.”52

Although the role the commanding officer played in establishing the efficiency, or effectiveness, of an infantry battalion was critical, much of the success or failure of a unit was pinned on the conduct of the senior major and the adjutant. Whereas the modern adjutant functions as the primary administrator to the commanding officer, exercising authority over personnel administration, regimental correspondence, and the dress, deportment, and conduct of the officers, in the Napoleonic era supervisory duties over the officers were performed by the senior major, who was to “superintend the drill of all officers on their first joining” the regiment, and to provide the junior officers with “the best advice and instruction.”53 Circumstances might also place the senior major in temporary command due to the prolonged absence of the commanding officer caused by employment on the staff (those working in a commander’s headquarters) or his becoming a casualty.

As Army Regulations provided for generous leaves of absence in peacetime for up to a third of captains who commanded companies and wartime absences due to employment on the staff, sickness, or casualties often left junior subalterns in control of companies, the “drilling of recruits” and their performance of the manual and platoon exercise — the tactical drill of the period — was the principal duty of the adjutant. As the adjutant “instructed” and “checked” the sergeant major and sergeants in the training of the men, he was often selected from among the sergeants. The adjutant was answerable to the commanding officer or, more often, to the senior major for the “progress and improvement”54 of the men. When the regiment was on the march, the adjutant and his sergeants oversaw the formation and dressing of the troops. The adjutant also had disciplinary duties, including carrying out punishments imposed by regimental courts martial, and administrative responsibilities, including compiling the monthly returns and regimental books.55

Between 1810 and 1817, Charles McCarthy, William Drummond, Robert Moodie, and Thomas Hunter held the post of senior major of the 104th Foot. Lieutenant Edward Holland, a former sergeant major, was adjutant of the 104th Foot from its formation until June 1812, when he was promoted and given company command. Determination of the officers who followed Holland is complicated by contradictory records, but they appear to have included Lieutenant John Jenkins, who replaced Holland, but left the 104th when he was offered a captaincy in the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles; Lieutenant George Jobling, who was adjutant until July 1813, when Ensign William McDonald, who had been sergeant major until he was commissioned as quartermaster in 1812, replaced him; and Lieutenant Fowke (Frederic) Moore, who followed McDonald in April 1814.56

William Gilpin was appointed regimental agent to the 104th Foot to assist the officers with the management and purchase of their commissions and exchanges between regiments and to manage the complexities of funds for recruiting, maintaining the regimental accounts, arranging contracts with clothiers and other contractors on behalf of the commanding officer, and acting as a bank on behalf of the Horse Guards and the Pay Office. Located on the Strand in London, Gilpin’s agency was one of twenty such offices that represented the financial interests of line infantry and cavalry regiments. The 49th Foot, then stationed in Canada, was the only other regular regiment Gilpin represented, but he also provided services to the militia in England. Gilpin had also served as agent for The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry, whereas the large firm of Greenwood, Cox and Company represented the Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Canadian fencible regiments.57

Many residents of New Brunswick welcomed the transfer of The Fencibles to the line, but it posed a number of difficulties for British officials, the most significant being the unit’s manning. The remarkable growth of the Army during the Napoleonic Wars was being offset by the loss of 23,000 men per year, which exceeded the number of available replacements. With the need to employ a force for home duties, garrison the Empire — including a host of recently obtained colonies — and support an offensive strategy in Europe, finding men to fill the ranks of over a hundred regiments, many with more than one battalion, was becoming difficult. Recruitment, rather than controlled centrally, rested with the individual regiments, which either kept a battalion at home to serve as a depot for new recruits or, if it became necessary to send all its battalions overseas, maintained a regimental cadre in Britain or Ireland to continue with recruitment. This was not the case, however, with the 104th.58

To bring the unit up to strength, recruiting parties, normally consisting of an officer, a few NCOs, privates, and, when possible, a drummer, fanned out across New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Their efforts, while enjoying success, were frowned upon, however, by Lieutenant-General Prevost, who interpreted them as being in violation of the general rules for recruitment, which did not permit foreigners to serve in regiments of the line.

The main source of manpower for the regular establishment of the British Army was voluntary enlistment or transfers from the militia in Britain and Ireland. Extraordinary sources of manpower adopted during the Napoleonic Wars included convicts, foreigners, foreign deserters, prisoners of war, and British boys. Convicts, prisoners, and deserters gained an unenviable reputation, however, and were generally useful only in penal corps. The recruitment of boys, who had to be at least sixteen years of age and at least five feet tall, was strictly controlled by the Duke of York, and they were never considered part of a unit’s operational strength.59 Foreigners — who included anyone not born in England, Scotland, or Ireland, or whose service did not make a demand on British manpower — provided a valuable source of manpower, and by 1813 they constituted just over 20 percent of the strength of the British Army. Before the Napoleonic Wars, the Army had often hired foreign troops, but after 1793 the French occupation of many European countries cut off the supply of men. Thereafter, dedicated foreign units, including the King’s German Legion, were created. Although concerns over the loyalty of foreigners serving in line regiments meant they “met with disapproval,”60 a number did make their way into the rank and file — including a number from British North America — but their total never amounted to more than 3.4 percent of the Army. Included in the roll of foreign units were the fencible units raised in British North America for local defence, releasing regular troops for service elsewhere.61

As it was raised outside of Britain, the 104th Foot faced unique challenges regarding its recruitment, which was exacerbated by unclear communication between the Horse Guards and the senior commanders in British North America. Raised abroad and without the advantages of a second battalion in Britain, the 104th was unable to recruit from “Home,” a complication that also rendered it unable to pay recruits a bounty, as did other regiments of the line. Indeed, in New Brunswick, Major-General Hunter’s proposal to Colonel Henry Torrens, the military secretary to the commander-in-chief of the Army, to raise a second battalion in Canada was rejected, as it would have exacerbated the manpower problem. Prevost’s opposition to the 104th’s efforts to recruit in the Canadas continued when he moved to Quebec, and in early 1812, knowing that a new fencible regiment was to be raised in Upper Canada, Colonel Edward Baynes, the adjutant general of the forces in British North America, instructed Hunter that recruiting in Canada was to cease that spring.62

In 1812, the matter was resolved when Gilpin, the 104th’s regimental agent, asked Baynes to clarify the “misconception of the Instructions and Regulations intended exclusively for Regiments which recruit at home” and “prevent the Recruiting Parties of that Corps [the 104th] being sent away from the Canadas.”63 The Horse Guards responded promptly, and in April advised Prevost that “it was never in contemplation to prohibit” the 104th “from receiving Recruits . . . from the several Provinces in British North America,” and that “it has always been the expectation, that from this source alone, this Regiment could be constantly kept Effective to its Establishment.” Torrens concluded with instructions that it was “His Royal Highness’ desire that every facility may be given on your part, towards the furtherance of this object.”64

With authority to recruit throughout British North America now clarified, the recruiting parties were permitted to proceed and, as was customary with single-battalion regiments serving overseas, an eleventh, or recruiting, company was formed for that purpose.65 Nonetheless, as had been anticipated, competition for the limited manpower grew between the recruiting parties from the 104th and those of other regiments, including the newly formed Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles, which was authorized for service in Upper Canada and also permitted to recruit throughout British North America, and a new provincial regiment, the Voltigeurs Canadiens, which was formed in Lower Canada. In the Maritime provinces the Nova Scotia Fencibles needed to be sustained, and in October 1812 a new fencible regiment in New Brunswick was formed, all of which added to the growing demand for men.66

Nonetheless, the 104th Foot found recruits, although this success was partially offset by routine losses to the regiment’s strength. Whether in peace or war, units routinely lost personnel for various reasons. For example, between September 1811 and June 1812, ninety-six “excellent” recruits joined the 104th and seven deserters decided to return to the colours, but their numbers were reduced by fourteen deaths, seventeen desertions, and the need to provide drafts to other regular regiments, including the 49th and 101st. The net effect was to reduce the 104th’s gain of 103 personnel to sixty-four.67 Indeed, whether in combat or not, the 104th Foot would continue to lose men to illness and desertion — a difficulty that would plague the regiment during its time in the Canadas.68

An inspection report for the 104th compiled in June 1812 provides excellent insight into the composition and character of the regiment. The return reported there were 54 sergeants, 50 corporals, 22 drummers, and 864 privates, for a total of 990 men. Of these, 391 identified themselves as English, Scottish, Irish, or foreign; 599, or 60 percent of the total, were described as “British Americans.” Unfortunately, the return does not identify the province of origin of these men, but many undoubtedly came from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. One man listed his birthplace as the United States.69

Because of their prior affiliation with The New Brunswick Fencible Infantry, many of the men had some previous military service. Most of the privates had between one and seven years of continuous military service, but ninety-nine had served for less than a year. Nearly half the sergeants had served for ten or more years, and one was reported as having been in uniform for thirty-three years. A similar level of experience was reported among the corporals. The 104th was also a youthful regiment, with half the men being between eighteen and twenty-five years of age; in contrast, two corporals were over age fifty-five.70

The regiment’s establishment consisted of forty-four officers: one colonel, one lieutenant-colonel as commanding officer, two majors, ten captains, twenty-two lieutenants, and eight ensigns. As was the case with the 104th’s predecessor, the majority held a regular commission in the Army. Most of the officers were present for duty, but two captains and ten lieutenants and ensigns were absent without leave; as well, five captains were on detached service, recruiting in the Canadas or holding staff appointments. Only three of the officers were identified as British Americans; the remainder were English, Scottish, or Irish. One, Captain George von Gerau, or Gerau de Hautefeuile, was foreign. Altogether, 114 men held commissions in both The New Brunswick Fencibles and the 104th, and of these sixty served with the 104th Foot during the War of 1812.71

As The Fencibles had been allowed to recruit in Scotland, many Britons accepted commissions in that regiment and continued their service with the 104th Foot. Such was the route taken by Coun Douly Rankin, a Scot who also helped to recruit thirty-four men from the Scottish Highlands whom he then brought to Fredericton. In 1810, the opportunity to gain a regular commission prompted him to seek a lieutenancy in the 104th. After the 104th departed for Canada, Rankin remained behind in New Brunswick and, in July 1816, following a dispute over his recruiting expenses, he was exchanged into the 8th Foot.

The 104th found its officers from other sources as well. In 1796, Andrew George Armstrong became an ensign in the 38th Foot, and in 1803 transferred to The New Brunswick Fencibles from the 6th West India Regiment. Three sons of James Rainsford, a Loyalist who settled in Fredericton following the American Revolutionary War, found appointments to the 104th, one of them later obtaining a commission in the New Brunswick Regiment of Fencible Infantry when it was formed in October 1812.72

From an operational perspective, the regiment was assessed as fit for service, and the majority of the men were fit and available for duty. Only forty-nine personnel were in hospital. The two field officers (majors) and the officers commanding companies (captains) were “effective and totally acquainted with their respective duties.” The NCOs were “attentive and tolerably instructed.” The privates were “strong, “hearty,” and “a good body of serviceable men, healthy and clean, but not well drilled.” The interior economy of the regiment was reported as “tolerable.” The regimental clothing was “according to regulation,” but lacking in certain pieces due to the distance they had to be brought. The 104th was equipped with 1,000 stands of arms that were also “serviceable, clean” and “in good order.”73

Major-General George Smyth, the officer who carried out the inspection and who had replaced Hunter earlier in the year as the president of the council and commander-in-chief in New Brunswick, was able to visit only eight of the companies, as the other two were on detached service. Six companies were in Fredericton, two in Saint John, and one each in Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton. Events would soon change this disposition and see the regiment move to the Canadas.74

The War of 1812: June 1812 to February 1813

In May 1812 US President Madison became convinced that further negotiations with Britain were useless. At the beginning of June, he therefore presented Congress with four charges against Britain — the impressment of American seamen, the violation of neutral rights and territorial waters, the blockade of American commerce, and the trade restrictions imposed by the Orders-in-Council — as sufficient grounds for a declaration of war. Congressional support was not unanimous, but following a close vote, both houses of Congress gave their approval. On June 18, a proclamation was issued declaring that “war exists between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the dependencies thereof, and the United States of America and their territories.”75

In New Brunswick, news of the American declaration of war arrived at Saint John after midnight on June 27. Major-General Smyth pleaded restraint in light of a declaration of neutrality by the District of Maine. In Halifax, Smyth’s superior, Lieutenant-General John Sherbrooke, repeated this call for restraint.76 Nonetheless, defensive preparations continued, and improvements were made to the defences around Saint John’s harbour. On Carleton Heights, five companies of the 104th under Major Drummond erected a blockhouse that became known as Fort Drummond (or the Drummond Blockhouse) and a battery armed with two guns to cover the western approaches to the town. As there were too few gunners to work all the ordnance, forty men commenced daily artillery practice under the direction of the Royal Artillery’s Lieutenant John Straton, who was also aide-de-camp to Major-General Smyth.77

Little work had been done prior to the war to improve the important communication route between Saint John and Quebec known as the Grand Communications Route. In autumn 1811, anticipating the need to transfer troops from the Maritime provinces to Quebec, Prevost ordered two officers to test a canoe-and-portage route across the line of the Maine-New Brunswick boundary to Rivière-du-Loup on the St. Lawrence River. Communications between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were also improved, and in the early weeks of the war, Smyth sent one of his aides-de-camp, Captain Thomas Hunter of the 104th, to determine a route from the St. John River to Fort Cumberland on the Bay of Fundy. Hunter was to proceed by bateau from Lake Washademoak and then locate portages and a suitable location on the Petitcodiac River, where a bateau drawing six inches of water could continue to Fort Cumberland. Finally, control of the St. John River and the route to Quebec City was to be maintained by posting a detachment from the 104th at the fork of the Oromocto River, where it was also to help construct a blockhouse.78

The Royal Navy’s presence ensured that Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were protected from any direct military threat from the United States. It was a different story on the high seas, however, as the US Navy and American privateers commenced a vigorous campaign against British merchant shipping. In July 1812, the privateer Madison succeeded in taking a British government transport of 295 tons that was en route from London to Saint John. The prize included bales of superfine cloths for officers’ uniforms, ten wine casks, one hundred quarter-casks of powder, drums, trumpets, camp equipage, and “830 suits uniforms for the 104th Regiment British infantry.”79

This would not be the last time the 104th would lose uniforms to the enemy. In March 1814, Callender Irvine, commissary general of purchases for the US Army, reported purchasing “eleven hundred Coats captured by a Salem Privateer which coats were intended for the 104th Regiment.” At four dollars each, Irvine considered them a “fortunate purchase,” as “there is no scarlet cloth in market.”80 Inefficiencies in the American supply system had created shortages of uniforms and caused delays in their distribution to units. A persistent shortage of blue wool cloth, the official US uniform colour, was partly overcome by the distribution of captured uniforms, including the coats intended for the 104th. Irvine described the clothing as “red Coats, white or buff collar, cuffs & tips handsomely ornamented,”81 and of “very superior quality.”82 Many of these uniforms were distributed to American soldiers, including enough for a “full band of musick”83 issued to the band of the US Regiment of Riflemen.84

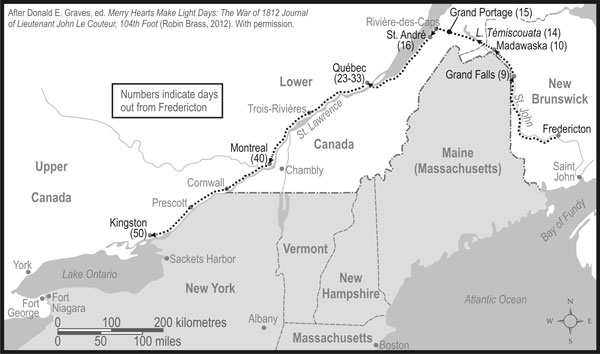

Northeastern British North America and the United States. The 104th Foot was stationed in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Cape Breton. MB

In January 1813, as he prepared for the opening of the campaign season, Prevost learned that, in addition to a naval contingent, he would receive reinforcements from other British garrisons. Experience had taught Prevost that the movement of troop convoys was subject to many disruptions that could delay their arrival at Quebec until the late spring or summer. In addition, transatlantic voyages in crowded troopships often left soldiers sick and weakened, requiring them to undergo a period of rest and recuperation before they could be employed. Unwilling to gamble on the timely arrival of the troopships and faced with evidence of American preparations for an offensive against Upper Canada early in the year, Prevost looked within the North American colonies for additional manpower. As part of this redistribution of troops, six companies of the 104th Foot based at Fredericton and a detachment of artillery were ordered to march overland to Quebec.85

Typically, the troops were not informed of what was being planned, but as training was stepped up to include marching on snowshoes, everyone knew something was afoot. Then, in early February 1813, the 104th learned it was to march to Quebec City and thence to Upper Canada. At the time, the regiment occupied the following garrison posts in New Brunswick, Cape Breton, and Prince Edward Island (including company commanders):

Fredericton:

Regimental Headquarters, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Halkett

No. 2 (Light) Company, Captain George Shore

No. 5 Company, Captain Edward Holland

No. 7 Company, commander unconfirmed

No. 8 Company, Captain Thomas Hunter

No. 9 (Grenadier) Company, Captain Richard Leonard

Saint John:

No. 3 Company, Captain William Bradley

No. 6 Company, Captain Andrew George Armstrong

No. 10 Company (Half), commander unconfirmed

St. Andrews:

No. 10 Company (Half)

Sydney:

No. 1 Company, Captain George Gerau

Charlottetown:

No. 4 Company, Captain William Proctor

The orders for the march were issued on February 5, 1813. For now, four companies, Nos. 1, 4, 7, and 10, and the boys were to remain where they were. The remaining six companies were concentrated at Fredericton, where the regimental headquarters would oversee the final preparations. Local militia were called up to replace the vacated posts at Saint John until the 2nd Battalion of the 8th Foot could arrive from Halifax to replace them.86

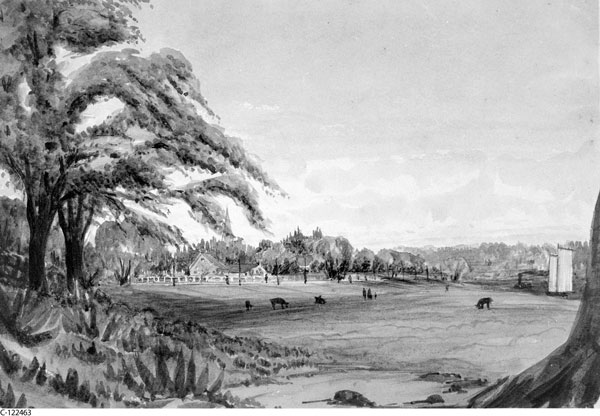

The regimental headquarters and several companies of the 104th Foot were stationed in Fredericton until early 1813, when the headquarters and six companies left for Upper Canada. Painting by W.S. Wolfe, LAC C-122463

The twenty-two officers, one paymaster clerk, the drum major, thirty-one sergeants, thirty-three corporals, fourteen drummers and buglers, and 452 privates were divided into six divisions, each based on a company that was to depart over five consecutive days. The regimental headquarters under Lieutenant-Colonel Halkett and the Grenadier Company commanded by Captain Leonard, forming the first division, left Fredericton on February 16, accompanied by four First Nations guides. Following them were Nos. 3, 6, and 8 Companies (the order by which these three companies marched cannot be confirmed), under Captains Bradley, Armstrong, and Hunter. On February 20, No. 5 Company under Captain Holland left, followed the next day by the Light Company commanded by Captain Shore. One soldier who was especially pleased to be leaving New Brunswick was Private Henry Grant. During a brawl in Saint John, Grant had killed a man, for which he was sentenced to two years in prison. With the 104th facing the potential of combat operations and requiring every man to be with his company, the officers arranged a pardon for Grant to accompany the regiment.87

As was customary, the departure of the regimental headquarters and individual companies was witnessed by the local populace, and the bugles “struck up the merry air”88 “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” an Irish tune with obscure origins, the words of which reflected a soldier’s sorrow over his parting from his beloved girl.

One important piece of regimental property that was carried on the march was the stand of Regimental Colours. When The New Brunswick Fencibles became the 104th Foot, the centre of the Regimental Colour was altered to include a badge with the numeral “104” in arabic lettering on a red circle, enclosed by a blue girdle with narrow white edging that stated “NEW BRUNSWICK REGIMENT” in gold letters, surmounted by a crown. A rose, thistle, and shamrock wreath surrounded the badge. Few references to the Colours appear, however, in period documents. One source is a recollection recorded nearly half a century after the march by Lieutenant Andrew Playfair, who remembered the fires lit during halts that sometimes consumed the brush and wood huts the soldiers constructed. On one occasion, during a fire in the officers’ camp, “the colours of the regiment” had “a very narrow escape.”89 Another reference to the Colours appears in April 1813, when Lieutenant-Colonel Halkett, accompanied by Captain Holland, his adjutant, took the Colours with them when they departed Quebec for Montreal. The location of the Colours thereafter remains unclear, but they might have been deposited at Montreal or in Kingston. Either way, given the piecemeal employment of the regiment in Upper Canada, it is improbable that the Colours of the 104th Foot were ever taken into the field or were present with the regiment in battle.90

The journey from Fredericton to Kingston was no small feat. The 104th was to cover a distance of some seven hundred miles, not by a well-defined road, but by a path that twisted and turned to avoid rapids, patches of bad ice, and difficult terrain along the St. John and Madawaska Rivers. The weather was abnormally cold, with greatly above average snowfall. The temperature dipped as low as –27 ˚C, and the troops endured at least one blizzard. These brutal conditions are even more striking given the clothing worn by the average soldier. The men had a black felt shako, red woollen coatee, white breeches — or, more likely, heavier grey trousers — and long black or grey gaiters. The red coatee was lined in light buff, which was also the regiment’s “facing colour,” a dress distinction that appeared on the collar, cuffs, lace (woven braid on the front of the coatee), shoulder straps, and turnbacks (the turning back of the coattails allowed freedom of movement, and exposed the inside colour of the coatee), and aided identification of the regiment. The double-breasted grey great coat provided some warmth and protection, and other items of winter dress, including wool and fur caps, mitts, scarves, and plume covers for the shakos, might have been issued. Footwear consisted of low-heeled shoes that were often poorly made or moccasins. The men also received a blanket to serve as bedding, and snowshoes were also provided on occasion.91 One participant described the clothing “as poor and scanty, their snow-shoes and moccasins miserably made; even their mitts were of poor, thin yarn.”92

By modern standards, the winter dress worn by the 104th Foot for the march from Fredericton to Kingston was insufficient. Aside from their uniforms, a double-breasted grey greatcoat provided some warmth and protection; other items of dress included wool and fur caps, mitts, and scarves. Footwear consisted of low-heeled shoes or moccasins.

Illustration by Drew Kennickell, courtesy of the St. John River Society

Each soldier’s accoutrements included sixty rounds of ammunition, carried in a cartridge box worn over the left shoulder, a haversack made of coarse linen or light canvas to carry rations, worn over the right shoulder, a bayonet and belt, and a wooden water canteen. On his back was a knapsack, also made of canvas or linen, which carried other clothing, such as shirts, a pair of shoes, stockings and socks, and toiletries, and when full weighed about forty pounds. Finally, there was the musket and sling. Altogether, the weapons and accoutrements weighed sixty pounds.93

The “Brown Bess,” the primary weapon issued to the soldiers of the 104th Foot. Courtesy of the Fredericton Region Museum

Most of the soldiers were armed with the British Short Land Musket, India Pattern, more popularly known as the “Brown Bess.” Weighing nine pounds, eleven ounces, and measuring fifty-five inches in length, with a barrel length of thirty-nine inches, the Brown Bess could fire a .71-calibre lead ball (the barrel had a .75-calibre bore) to a theoretical range of 250 yards. Due to imperfections in the powder, shot, and weapon, and the windage created by the smooth-bore barrel, the ideal range was between 100 and 150 yards. It took eleven drill movements to load, present, and fire the weapon, and despite claims that a rate of up to four or five rounds a minute was possible, a well-drilled soldier generally fired three to four rounds per minute in battle. Impurities in the powder, the build-up of residue in the firing mechanism, and damp weather could also result in a misfire rate of between 20 and 40 percent. As well, smoke from the weapon often impeded the target’s visibility. These limitations necessitated the tactic of employing tightly packed formations of men, dressed shoulder to shoulder in ranks, whose volley fire would inflict maximum casualties on their opponents. A seventeen-inch-long socket bayonet could also be fitted to the Brown Bess, but it was normally used as a psychological weapon against the enemy — although, on active service, there would be many occasions for close-quarter fighting.94

When it was formed in 1810, the 104th inherited the remnants of the one thousand muskets and bayonets that had been issued to The New Brunswick Fencibles in March 1805. In October 1812, the 104th received six hundred light muskets and thirty sergeants’ fusils — a lighter and shorter-barrelled version of the India Pattern musket that was often issued to boy recruits — and weapons that had become unserviceable were replaced during the march to Kingston and later during the course of wartime service in Upper Canada.95

A depiction of travel on the St. John River on the way to Quebec in early 1815 by Royal Navy purser and artist E.E. Vidal. New Brunswick Museum W6798

Instead of a musket, the officers carried edged weapons, which served as both status symbols and weapons. Most were equipped with the 1796 pattern straight-bladed infantry sword or the 1803 curved-bladed sword. The latter pattern was a particular favourite of the officers serving in the flank companies, especially among those in the light company. Sergeants also carried swords, but their sign of office was a seven-foot-long wooden staff surmounted by a thirteen-inch-long metal spearhead known as a spontoon or halberd. These staffs served a number of functions, including providing a useful tool for dressing the ranks, closing blank files caused by casualties, and as a rallying point during battle. Although swords and pikes fulfilled important requirements, they had limited tactical use and deprived the regiment of firepower.96

Except for those few occasions when sleighs were provided, the 104th marched on foot, with or without snowshoes. Each company was divided into a number of squads, with each pair of men using a small toboggan to carry their knapsacks and weapons; the officers carried their own knapsacks. The toboggans were made of hickory or ash, and were about six feet long and one foot wide. The men marched “Indian style,” or in single file, so that each company formed a line about half a mile long.97 According to Playfair, “[t]he train of the 104th (one company) consisted of upwards of 50 toboggans, containing each two firelocks and accoutrements, two knapsacks, two blankets . . . , and two pairs of snowshoes . . . each toboggan being drawn by one man in front and pushed or held back, as necessity required, by one man in the rear by a stick made fast to the stern of the toboggan, Indian fashion.”98

Before leaving Fredericton, every man received fourteen days’ rations. Each ration included one pound of pork and ten ounces of biscuits, tea, and coffee. The officers also provided supplements such as chocolate. At various points along the route, the commissariat issued additional rations, while the few civilians who were encountered offered wine, beer, and food. The physical exertions created by the difficult conditions and the cold caused the men to consume their rations faster than anticipated, leaving them without food on several occasions. Playfair recalled one instance when he “experienced a fast of 30 hours,” after having consumed a “half pound cake of chocolate” for his breakfast, and there was “[n]o dinner that day, no supper that night, no breakfast the following morning.” It was only when his column reached Rivière-du-Loup that he “found two men, with bags of biscuits and two tubs of spirits and water, handing each” man “a biscuit and about half a pint of grog.”99

When shelter was not available along the route of their march through New Brunswick, the officers and men of the 104th Foot constructed huts, as depicted here. The men used their snowshoes to dig into the snow, and roofed over the huts using logs and tree branches. Illustration by Drew Kennickell, courtesy of the St. John River Society

Accommodation, when it could be provided, varied from barracks, as when the regiment halted at Presqu’Ile, Grand Falls, Quebec, and Montreal, to houses, barns, and makeshift huts built by the men in the woods. Making the huts generally involved clearing an area of snow, “felling young pine trees [about fifteen feet in length] to form the rafters of the hut,” then placing the trimmed trees “in a conical or lengthened form with ties at the top.” The branches were then covered with a thatch of pine boughs. Snow was thrown around the outer ring, forming a thick wall. Inside, a floor was fabricated from small pine branches, and “a blazing fire was then lit in the centre of the hut.”100 Pine branches were stacked inside to make beds.

The route of the march through New Brunswick paralleled the St. John River, and it took about twelve days to slog from Fredericton to the frontier of Lower Canada. From there, the journey continued to the south bank of the St. Lawrence River at Rivière-des-Caps, which the leading division reached on March 8. The divisions then continued on foot along the south shore of the river, averaging between eighteen and twenty miles a day, to Point-Lévis, where they crossed to Quebec City. The first division arrived there on March 13, having completed a journey of three hundred and fifty miles in about twenty-four days. The last division entered the city three or four days later. The men were quartered in the Jesuit barracks, and were immediately placed on garrison duties.101

After such an arduous march, the troops must have found garrison duty an annoyance. Each day, the garrison contributed personnel to the guard that protected the city. Between them, they provided four duty officers (one field officer, and three captains and lieutenants, one to act as adjutant) and nearly three hundred NCOs and men to protect vital points, occupy pickets, conduct patrols, and provide escorts for prisoners and other personnel. On March 27, 1813, the guard was drawn from the Royal Artillery, and four infantry regiments, with the 104th providing thirty-six men for guard duty and another thirty-three to man the pickets. This routine continued until March 29. Until they left for Upper Canada, the commanding officer and other officers also made themselves available for other duties, including membership on boards of inquiry and courts martial, while Surgeon William Thomas temporarily gained responsibility for the sick of the 1st Foot, as its surgeon had been assigned elsewhere.102

Instructions also directed that, if Quebec were attacked, an alarm would be sounded by three guns firing in quick succession. All the gates to the city would be closed, and units in the garrison would occupy specific positions in the city. If the alarm sounded, the 104th was to occupy posts along the eastern edge of the Upper Town. Two companies were to hold a line between the governor’s residence at the Palace of St. Lewis and the nearby Hope Gate; another company would be detached to Grand Battery, overlooking the river basin; while a fourth company was to take post between the Palace of St. Lewis and the Carronade Battery. The flank companies were to remain under arms at the Jesuit Barracks square, near the city centre, ready to react to any orders. Fortunately, no threat appeared to cause these plans to be implemented.103

In mid-March 1813, Prevost inspected the 104th Foot. On parade were 28 officers, the sergeant major, 32 sergeants, 31 corporals, 11 buglers, 469 privates, and a boy. Paying them the “highest compliments,” Prevost “thought” them to be “really good wind.”104 In his report to the Horse Guards, he noted that the condition of the 104th was better “than was expected, from the severity of the season for which it has been performed.”105 Despite its recent ordeal, the sickness rate in the 104th was no worse than in most other units in the city’s garrison. In the month from February 25 to March 24, 1813, twenty-five men of the 104th entered hospital, sixteen of whom were released. The diseases of those remaining in medical care included dysentery and ulcers to the body.106

After nearly a fortnight, the companies were ordered to continue on to Montreal and then to Kingston. The flank companies, commanded by Major Drummond, left immediately, while the remaining four companies would “march to Montreal and from thence to Kingston in two Divisions.”107 The first division, commanded by Major Robert Moodie left on March 29, and the second, under Lieutenant-Colonel Halkett, left the following day.108

Each soldier received six days’ rations and a blanket, and the quartermaster general also provided sleighs to carry equipment and provisions. Shortfalls in weaponry were made up by the issuing of twenty-five muskets and twenty-four bayonets to the regiment. As the campaign season was about to open, speed was essential, and “no superfluous stores or heavy baggage was to be carried.” Once the divisions arrived at Prescott, in Upper Canada, a detachment was to hasten to Kingston to give “notice of their arrival”109 there. The first division left Quebec on March 25 and was in Montreal on April 1. The stop at Montreal would be brief, as the march was to continue the following day.110 The flank companies under Major Drummond arrived at Kingston on April 12, followed by Moodie’s division about four days later. Halkett and the last two companies went into barracks at Coteau-du-Lac, about fifty miles west of Montreal, until the beginning of May, when they proceeded to Kingston, arriving there on May 10.

The 104th had suffered a number of casualties during the march from Fredericton to Kingston. In March, Private William Lammy, from Captain Holland’s company, had died near Woodstock. Private Stephen Wadine had frozen to death, and another five soldiers also might have died. Frostbite had afflicted an unknown number of men, including Private Reuben Rogers, who was left near the beginning of the Grand Portage Route; he later rejoined the regiment, only to perish under unknown circumstances in May 1814. One man had deserted. The survivors, in their worn and tattered uniforms, covered in mud and dirt from the final stages of the march, and sickly from their exertions, must not have appeared inspiring either to the officers and men of the Kingston garrison. To give an idea of the pace, the grenadier and light companies of the 104th had taken fifty-three and fifty-seven days, respectively, to march from Fredericton to Kingston, at an average rate of seventeen miles per day. Despite those lost and sick, however, the officers and men of the 104th Foot had achieved the goal they were given, and the six companies now undertook preparations for the coming campaign season.111

The final part of this story rests with the two line companies and boys that had remained behind in New Brunswick, and the soldiers’ wives and children. Regulations and custom allowed regular regiments on overseas duty to embark with six “lawful wives” and their children to every “One Hundred Men.”112 As not all the families could accompany their men, the women would cast lots before the unit embarked. This rule did not apply to fencible units in North America, but when The New Brunswick Fencibles were redesignated the 104th Foot, the regulations would have allowed sixty wives to be with the regiment. Instead, the June 1812 inspection reported 157 wives and 280 children, only 16 of whom were age ten or older. To help meet the educational requirements of these children, in December 1811 Corporal Thomas Welsh was appointed schoolmaster sergeant, a new post recently approved for all regiments of the Army.113