Kingston, Sackets Harbor, and the Niagara Peninsula, April-June 1813

Our young troops went into action admirably.

— Lieutenant John Le Couteur, May 29, 1813

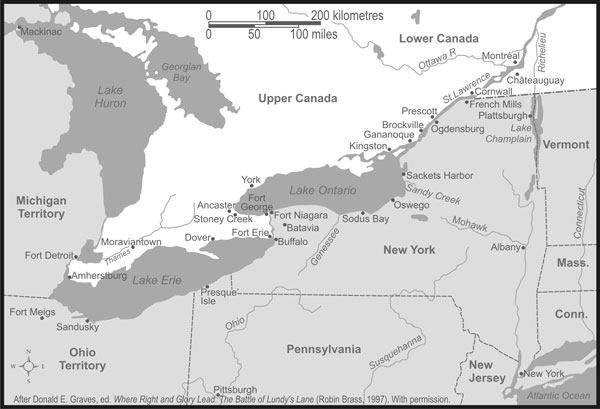

At the outset of the War of 1812, Kingston was the largest community in Upper Canada, with a population of one thousand. Situated on the west side of Kingston Harbour, Kingston, or Cataraqui, as it was first known, was established in 1673, and eventually included a fort that served as a depot and transit point for French communication with the interior of the continent. In August 1758, a British force took the fort, leaving it in ruins and the area largely unsettled, until the end of the American Revolutionary War revived the strategic importance of the location. Beginning in 1783, the community was re-established, while across the harbour a naval base for the Provincial Marine, the naval force operating on the Great Lakes, was established at Point Frederick. In November 1812, a recently established US naval squadron on Lake Ontario chased the flagship of the Provincial Marine into Kingston’s harbour, giving the Americans control of the lake.

By the spring of 1813, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Halkett had taken command of the garrison of Kingston from Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Pearson, and assumed responsibility for the defence of the town, the Provincial Marine base at Point Frederick, and the recently established fortified camp atop Point Frederick, on whose slopes a tented campground accommodated a portion of the garrison and those units transiting to points farther west. Halkett was also responsible for ensuring the garrison’s logistical requirements. In May 1813, approximately 584 regulars were stationed at Kingston, along with a varying number of sedentary militia. Fourteen pieces of ordnance of differing calibres had been positioned in blockhouses protecting the western approaches to the town and at Point Frederick and Point Henry.1

Map from 1839, based on an original drawn in the spring of 1813 by Captain Jacques Viger of the Voltigeurs Canadiens around the time the 104th completed its march to Upper Canada. During its stay in Kingston, the 104th Foot was garrisoned in the town and at Points Henry and Frederick. Courtesy of the Musée de la civilisation, Quebec City

During the winter of 1813-1814, Lieutenant John Le Couteur secured lodgings at this house belonging to Elizabeth Robison, the daughter of a prominent local merchant, politician, and militia officer, at the corner of Gore and King Streets in Kingston. Photograph by author

During the course of the war, the naval and military presence grew to dominate Kingston. The large number of officers, soldiers, and sailors created crowded conditions, as the existing barracks space proved inadequate. Hired storehouses were converted to barracks to hold anywhere from a few to 250 officers and men; a large tented camp was also erected at Point Henry. By 1815, these newly acquired facilities could accommodate between 1,700 and 2,800 men. The conditions during the spring of 1813, however, made it impossible to concentrate the 104th Foot in one location, and the companies were dispersed between Point Henry — where the light company was encamped in tents until the completion of proper barracks — and Kingston, where sleeping quarters were provided in buildings, blockhouses (which could accommodate 120 men each), and other defensive works. Many of the officers, including Captain George Shore and Lieutenant John Le Couteur, found rooms in private dwellings, hotels, and other buildings set aside for this purpose.2

In April 1813, the Americans opened the campaign season by exploiting their control of Lake Ontario. Their plans called for a joint attack force of five thousand regulars and militia, who would assemble at Sackets Harbor to attack Kingston, York (Toronto), and Fort George on the Niagara front. As American intelligence indicated the defences at Kingston were formidable, it was decided to attack York and hold it until a British relief force could be detached from Fort George to reclaim the town. The Americans then would make a lightning move across Lake Ontario, reduce Fort George, and, aided by an army that would cross the Niagara River, secure the Canadian side. Afterwards, Kingston was to be blockaded to contain the British naval squadron. Commodore Isaac Chauncey would then proceed to Lake Erie to destroy British naval power, and thereafter “attack and take Malden and Detroit, & proceed into Lake Huron and attack & carry Machilimackinac [Mackinac].”3 The American plan was complex in design and offered many challenges in execution.

The enemy’s objective at York was to destroy naval stores and weaken British naval strength by capturing two 18-gun brigs under construction at the dockyard and two Provincial Marine schooners, which, according to Chauncey’s sources, were wintering at the provincial capital. At York, Major-General Robert Sheaffe could muster only 413 regulars, 477 militiamen, 50 First Nations warriors, and about 100 miscellaneous personnel consisting of the staff, town volunteers, and members of the Provincial Marine. The town’s main defences were a fort, four battery positions, and several unarmed works. Sheaffe actually anticipated that a determined attack on York would likely succeed, and he hoped to finish Sir Isaac Brock, the sole vessel being built at the dockyard, before the Americans could sail; he had already sent Prince Regent to Kingston as soon as the ice cleared. Completion of Brock was delayed by supply problems, however, and by difficulties between the shipbuilder and government officials.4

During the morning of April 27, 1813, the Americans began landing a large body of troops to the west of the town. Superior numbers and fire support by Chauncey’s squadron overwhelmed the defenders, who began to withdraw to York. By the time he reached Fort York, Sheaffe realized the battle was lost, and ordered Brock and the naval supplies burned. He then prepared to withdraw to Kingston, leaving the militia, which had arrived too late to influence the outcome, to surrender the town.

One witness to the debacle was Captain Robert Roberts Lorimer. Born in England in 1789, Lorimer had joined the 49th Foot as an ensign in 1804, and two years later arrived at Quebec with his regiment. His commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Roger Sheaffe, noted Lorimer’s talent for staff work and appointed him adjutant. Another future wartime commander of Upper Canada, Gordon Drummond, also found Lorimer to be a talented officer; Drummond appointed Lorimer to his staff while he was at Quebec between 1808 and 1811 working for Sir James Craig, the governor-in-chief of British North America. In 1811, Lorimer accompanied Drummond back to Britain and, upon learning of the opening of hostilities with the United States, returned to North America, where he obtained a captaincy in the 104th Foot. In October, Sheaffe, now a major-general and commander of Upper Canada, brought Lorimer back to his staff as aide-de-camp.5

Lorimer was present when Sheaffe gave the order to evacuate York. They separated as Lorimer rode to Sheaffe’s official residence, located near the grand magazine at Fort York, to retrieve what important documents and money he could find. A cataclysmic eruption took place when three hundred barrels of black powder in the grand magazine exploded, throwing tons of stone, earth, wood, and metal, as well as men, into the air. The falling debris killed Lorimer’s horse, but despite sustaining a serious wound to his right arm, Lorimer got to his feet and continued eastwards on foot, and eventually reached Kingston.

The Americans, meanwhile, found their attack had been only partially successful.6 The detonation of the grand magazine occurred just as the Americans approached the fort, and the debris, falling as far as five hundred yards away, caused two hundred and fifty casualties among the enemy, including Brigadier-General Zebulon Pike, commander of the troops ashore. Then, contrary winds and poor weather forced the Americans to remain at York for several days. By the time they could leave, fatigue and sickness had weakened their men so much that Major-General Henry Dearborn, commander of the northern theatre, cancelled plans for a direct assault on Fort George, and the American troops and naval squadron returned to Sackets Harbor to rest and refit.7

Following the British evacuation of York in April 1813, elements of the 104th Foot deployed to the west of Kingston, where they were to guide the withdrawing troops into friendly lines and thwart any threat from pursuing American troops. Here, British troops destroy a bridge over the Don River as they begin their march to Kingston. LAC C6147

The state of the American forces was unknown to the British, however, and given the uncertainty of enemy intentions following the raid on York, the British troops at Kingston remained at high readiness to repel any attack. At the end of April, a report reached Halkett that York had been surrendered to the Americans and that the surviving British troops, including Sheaffe, were withdrawing to Kingston, pursued by American troops. Halkett immediately appointed Major Drummond to proceed with the grenadier company of the 104th and a group of First Nations warriors to the Bay of Quinte, about forty miles to the west, from where he was to support Sheaffe’s column on the final leg of its march to Kingston. In compliance with a request from Sheaffe to send “up boats and Provisions for the troops,”8 Halkett had bateaux loaded with enough food to feed a thousand men for three days. To protect the approaches to Kingston, Halkett established guards on the three bridges spanning the Cataraqui River, about three miles west of the town. Thirty Voltigeurs Canadiens, commanded by Captain Jacques Viger, and ten men from the 104th under Lieutenant Le Couteur were assigned the centre bridge, where Sheaffe and the remnants of the garrison from York were expected to cross.9

“Expecting that an engagement was at hand,”10 Viger prepared the bridge for demolition, established sentry positions, and sent warriors ahead to scout for the enemy and to provide warning of the approach of Sheaffe’s column. Conditions worsened, as it began to rain heavily, turning the roads into a muddy morass. The only contact came from “wayfarers, cattle drovers and countrymen,” and militia sent to reinforce Viger’s men. When it became apparent that the enemy was not approaching, all three detachments returned to Kingston. Sheaffe eventually arrived at Kingston on June 2, followed by the main body of the column from York three days later.11

The fallout from the surrender of York and logistical concerns were the least of the problems facing the 104th’s commanding officer. Earlier, when Halkett had departed Montreal for Kingston, Major-General Sir Francis de Rottenburg, the commander of the district between those two points, had ordered him to halt at Coteau-du-Lac. Believing the order applied to the two companies he was travelling with and not him, Halkett continued to Kingston. When de Rottenburg complained to Lieutenant-General Prevost of this apparent disregard of his orders, the commander-in-chief issued a General Order chastising Halkett for his “direct disobedience to” de Rottenburg’s “express orders” and ordering him “instantly”12 to return to Coteau-du-Lac, where he was to explain his reasons for not following de Rottenburg’s instructions. Disappointed by this turn of events, and slighted by this public rebuke that was so “injurious to” his “feelings,”13 Halkett concluded that his “services” were “by no means properly appreciated” and requested a leave of absence to “return to Europe.”14

In his defence, Halkett claimed that, since four companies of his regiment were already in Kingston, he considered it necessary to establish his headquarters there. Halkett did not help matters, however, when he wrote that, while he was in Quebec, the adjutant general for Canada, Colonel Edward Baynes, had informed him that “there was no necessity” for his “proceeding with the Regiment”15 to Kingston, as his brevet promotion to colonel was expected and he should remain behind to await a new assignment, a detail that de Rottenburg likely knew. In May, the matter worsened following the arrival of Prevost at Kingston, accompanied by the new naval commander on the Great Lakes, Commodore Sir James Lucas Yeo. Prevost inspected the 104th “at their respective posts.”16 In contrast to his first inspection of the regiment in Quebec in March, where the regiment was found to be “in good health,”17 Prevost now found the clothing, shoes, and other equipment to be worn out and the men “sickly … not appearing in their usual good order and looks.”18 On the following day, the results of the inspection appeared in a general order, and Halkett became “fully convinced” that he had “no prospect of getting a Command.”19 Following approval of his leave of absence, Halkett left Kingston in May, just as the 104th was preparing for its first action, his request to accompany the troops having been unanswered. Dejected, Halkett returned to his home in Scotland, where, in June, he was promoted to major-general. Halkett was later knighted, but he never held another command.20

In June, following Halkett’s departure, newly promoted Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond “assumed command of the troops” on Point Frederick, and Robert Moodie, now also a lieutenant-colonel, replaced Drummond in “command of the troops at Point Henry.”21 Any hopes Drummond, the more senior of the two officers, had of taking command of the 104th ended in June, when the talented and experienced officer was appointed acting deputy quartermaster general, leaving Moodie in command. Captain Richard Leonard was appointed brigade major of the Kingston garrison, and became responsible for the readiness and employment of all the units stationed there, including the preparation and issuing of orders and instructions related to their duties.22

In the meantime, on May 27, 1813, the enemy struck again when, following a two-day bombardment of Fort George, an American army landed on the Niagara Peninsula. Its objective was to encircle and capture British forces in the area of Fort George. Brigadier-General John Vincent, commanding in the Niagara region, had anticipated that the enemy might be too strong for his own forces, and implemented a contingency plan, withdrawing his command to the safety of Burlington Heights. The following day, two American brigades, totalling three thousand soldiers, set out in pursuit. Heavily outnumbered, and with Chauncey commanding Lake Ontario, the British found themselves in a difficult situation.23

On May 26, Prevost was still at Kingston where, after studying reports that Fort George was under tremendous bombardment, he concluded that this was a prelude to an enemy assault on the fort, and proposed a bold plan to relieve pressure in the Niagara region and divert American attention by attacking the enemy naval base at Sackets Harbor. Prevost first conceived this idea on May 22, when an American spy confirmed that Chauncey’s squadron was at the western end of Lake Ontario. A reconnaissance conducted on May 26 confirmed that Chauncey’s squadron was indeed absent and the American garrison appeared weak. Once he knew that Fort George was under heavy bombardment and that Chauncey was supporting the assault on the fort, Prevost appointed Colonel Baynes to command the raid and began planning in earnest. Prevost was “[d]etermined in attempting a diversion in Colonel Vincent’s favour by embarking the principal part of this small garrison of this place and proceeding with them to Sackett’s Harbour [sic].”24 Chauncey’s departure for the Niagara Peninsula also made the naval stores and the General Pike, an American ship under construction, a tempting target. On May 27, units were mustered and the squadron readied for departure.25

The Raid on Sackets Harbor, May 27-29, 1813

In addition to the warships of Yeo’s Lake Ontario squadron, the assault force included some nine hundred men of the Kingston garrison. The attack force was drawn from the light companies of eight different regiments and included two field artillery pieces and forty First Nations warriors. Fewer than one-third of the regular troops had seen any action. Whatever concerns Prevost had expressed about the 104th Foot following his inspection of the regiment were forgotten as Major Drummond was placed in command of a four-company detachment totalling nearly a third of the entire assault force. Which battalion companies were selected is not altogether clear from the returns and reports, but it is likely that the contingent included No. 3 Company commanded by Captain William Bradley, No. 6 Company under Captain Andrew George Armstrong, and both flank companies, No. 2 (Light) Company commanded by Captain George Shore, and Captain Richard Leonard’s No. 9 (Grenadier) Company. Major Moodie and Captains Edward Holland and Thomas Hunter also accompanied the expedition.26

With the company bugles “sounding and Drums rolling” at Point Frederick and in Kingston, the detachments of the 104th manning the defences were quickly marched back to Kingston. At Point Frederick, a soldier from the light company informed Lieutenant Le Couteur that “there is some great move.” Together, the two men rushed to find a means of crossing the harbour to Kingston. Unable to find a boat, the soldier, a native of New Brunswick and “thorough Canoeman,” suggested they try one of the abandoned, unserviceable canoes. They clambered into one end, forcing its broken bow into the air, and crossed the harbour.27

One of the men rushing to the rendezvous was a volunteer serving in the ranks. On the eve of the War of 1812, John Winslow, who was from the same family that had disapproved of Colonel Halkett’s enjoyment of alcohol, was a lieutenant in the 41st Foot at Fort George. A disagreement in the mess with another officer had resulted in a brawl, and when Major-General Isaac Brock learned of the incident, he demanded that both officers submit their resignations. Unable to salvage his career or Brock’s opinion of him, Winslow decided to become a volunteer, and fought in the Battle of Queenston Heights. Impressed by this act, Brock’s replacement, Major-General Sheaffe attempted to reinstate Winslow, but his appeal found little support; Winslow’s commission was finally revoked in May 1813. By this time, Winslow was in Kingston, and in an effort to regain his name, he enlisted in the 104th Foot as a gentleman volunteer, meaning he would serve as a soldier until a commission became available.28

On May 27, Winslow embarked in one of the boats for Sackets Harbor, and later that year, when the 104th was sent to the Niagara Peninsula, he was attached to the light company. In 1814, he returned to the Niagara and fought at Lundy’s Lane. Despite his commanding officer’s frequent offers of an ensigncy, Winslow insisted that his name be cleared before he would accept a commission. In late 1816, Lieutenant-Colonel Moodie, who described Winslow’s conduct as “conspicuously gallant” and his behaviour always “that of a gentleman,”29 made one final appeal to Lieutenant-General Sir Gordon Drummond, who had replaced Prevost as captain general and governor-in-chief of British North America, to clear Winslow’s name. The result was that, in October 1817, Winslow regained his commission, but as the Army was being reduced, he was placed on half-pay without any hope of active service.30

As the companies formed up in Kingston and the officers and NCOs checked to ensure the men carried their haversacks and sixty rounds of ball cartridge, word quickly spread that their destination was the American naval base at Sackets Harbor. Soldiers from Nos. 5 and 8 Companies, commanded by Holland and Hunter, were used to bring those companies selected for the expedition up to strength. Around midday, the men began filing onto the boats that had been assembled in Navy Harbour, between Point Frederick and Point Henry.31

Commodore Yeo’s squadron included eight hundred sailors distributed among five ships armed with a total armament of eighty-two guns, a merchantman, thirty-three bateaux, three gunboats, and several canoes. With only a single civilian transport to carry part of the infantry and the two field guns, most of the soldiers were crowded onto the open decks of the warships, leaving little room for the ships’ companies to do their work. Moreover, the extra load the vessels had to carry affected their handling. An unfortunate few men were also carried in the bateaux that were towed behind the ships for the thirty-six-mile journey. Just before sailing, a canoe delivered Prevost and his staff to Yeo’s flagship, Wolfe.32

On the night of May 27, the squadron got under way and made good progress until early the next morning, when the wind died. During the night, an American schooner spotted the squadron and fired a shot to warn the garrison at the harbour before returning to base. By 4:30 a.m. on May 28, the British squadron was within sight of its objective, now about ten miles away. At dawn, Captain Andrew Gray, serving on the staff of the quartermaster general’s department, made another reconnaissance while the troops prepared to land. Upon his return at 9:00 a.m., Gray offered the welcome news that the American base appeared weakly defended. Elated by this intelligence, Major Drummond ordered his troops into the bateaux “to practice pulling,”33 and then had them turn toward the landing site, only to be called back by one of Prevost’s aides.

An hour later, the naval squadron and flotilla of bateaux were still seven miles from their objective when the wind faltered. Yeo then decided to make a personal reconnaissance; when he returned at 3:00 p.m., he and Baynes agreed to call off the attack and the squadron turned back to Kingston. Shortly thereafter, the wind shifted against the British once more. Then, a detachment of thirty-seven warriors and a number of regulars who had been sent out from the squadron in three canoes and a gunboat captured 115 American reinforcements en route to Sackets Harbor. Elated, Baynes and the other senior officers now decided that the ease with which fifteen boats from the American convoy had been captured — most of the 130 survivors in the remaining boats had landed at Stoney Point and scattered into the woods, and only a single boat arrived safely at Sackets Harbor — indicated that the troops at Sackets Harbor were of poor quality. As a result, they recommended the attack go forward, and Prevost gave his consent.34

As the decision to proceed with the raid came late in the day and the squadron was still some distance from the proposed landing site, the British were forced to remain off the harbour that night. Several participants later claimed this delay allowed the Americans time to muster the militia and occupy their defensive positions, which might have been avoided had Yeo’s recommendation for an immediate assault been acted upon. In fact, had the landings been conducted in the late evening or night of May 28, the attackers would have found the defenders already in position and with the coming darkness in their favour. As well, the weather to this point had been fine, but as night fell, a heavy rain soaked the men, who, in their haste to board the ships, had not taken their greatcoats.35

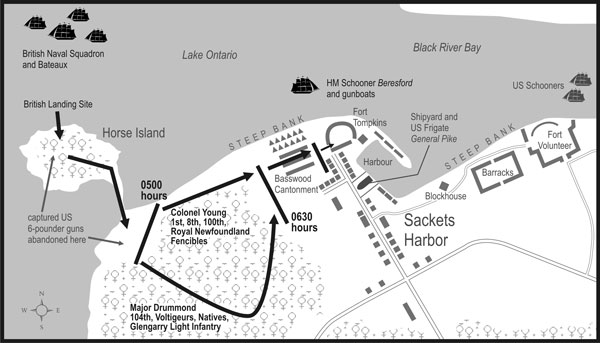

The defences at Sackets Harbor were considerable. Colonel Alexander Macomb, the officer who commanded the garrison in early 1813, had anticipated correctly that the British would avoid a direct descent on the base as the approaches were well covered by the guns of two forts. Instead, he expected they would establish a foothold on Horse Island, about a mile west, cross a narrow channel to the mainland, and then advance toward the village. Even if the British overwhelmed the troops defending Horse Island, they would still have to negotiate a massive obstacle constructed from hundreds of felled trees — known as an abattis — that encircled the town and dockyard. The main American defences centred on three log barracks, where a regiment of dismounted dragoons and elements of three regular infantry regiments, equivalent in number to the entire British assault force, were expected to defeat any attack. Behind them was Fort Tompkins, surrounded by a stockade and armed with a powerful 32-pounder gun. Farther beyond that, in the low ground, was Navy Point, covered by six guns ranging from 12- to 32-pounders manned by experienced sailors. Overlooking the harbour from the high ground to the east was Fort Volunteer, armed with six or seven guns. Altogether, the strength of the defenders amounted to 1,500 men, which outnumbered the attacker’s ground force, and sixteen or seventeen pieces of ordnance, which gave them an eight-to-one advantage in artillery. To reach the naval base, the British would have to sweep aside the militia protecting the beachhead, get through the abattis, then overwhelm the regulars in the main defensive area. Even this was no guarantee of success, for the Americans were prepared to destroy the naval warehouses and their ship rather than let them to fall to the British.36

Around 4:00 a.m. on May 29, the tired, wet, and shivering troops moved into the bateaux, formed into line, and headed for the American shore. During the final run in, several of the officers induced Drummond to make his appearance less conspicuous by removing the epaulettes from his uniform, and he agreed, tucking them into his overalls. Any belief the landing would be unopposed was shattered when the New York State militia opened fire as the boats got within a hundred yards of the beach.37

As the men poured out of the boats onto the northern shore of Horse Island, the gunboats pulled ahead, firing into the trees and bushes with canister. The 32-pounder gun in Fort Tompkins then opened fire, and one round struck a boatload of grenadiers from the 104th, “killing and wounding a couple of men, cut the boat nearly in two, and down she went.”38 As morning dawned, troops from the companies pushed across the island to a causeway linking it to the mainland. The fire from the American 6-pounder gun and the militia increased, adding to the casualties. As the attack moved forward, Captain Leonard fell severely wounded, while Lieutenant Andrew Rainsford received a shot in the abdomen that knocked his sword from his hand, and Lieutenant James DeLancey was hit in the arm. Around them, other men fell killed or wounded.39

Nonetheless, the British secured the island, and the companies from the 100th, 1st, 8th, and 104th Foot, in that order, prepared to charge across the causeway to the mainland, while the gunboats positioned themselves to provide fire support. With their bayonets fixed, the 100th moved quickly onto the causeway, causing a stampede among the undisciplined defenders. The 104th followed, and as the men rushed across, they became engulfed in a dense cloud of grey smoke created by weapons firing. Suddenly, as they continued toward the shore, they came under volley fire that erupted from their rear. Understanding what had happened, Major Drummond ran back, waving his arms at the grey-clad soldiers firing from the island and yelling that they were firing at friends. It turned out that, moments earlier, as Drummond’s men began crossing the causeway, the Voltigeurs Canadiens, the last unit to land, had moved to the southern end of Horse Island and established a firing line. Thinking that the troops moving through the smoke to their front were Americans, the Voltigeurs had opened fire, but instead of finding the enemy, their rounds had struck the backs of the 104th. Drummond’s intervention came quickly, but not before eight of his men had fallen.40

The main battlefield at Sackets Harbor. The American defences were among the three barracks buildings located in the wooded area at the centre of the photo. Despite repeated assaults, the British and Canadian attackers were unable to break through the defences and reach their objective, the naval dockyard beyond. Photograph by author

Meanwhile, the forward companies had cleared the enemy from the far shore. During the action, Drummond, with sword in hand, had charged toward the Americans. When he was about twenty yards from the enemy, an American soldier levelled his piece at Drummond and fired, knocking him over, apparently dead. Soldiers from the 104th closed in, bayoneted the man, and then turned to see to Drummond. As they began lifting his body from the ground, Drummond grunted out, “tis not mortal, men, I can move my legs.” Then, getting to his feet, the badly bruised officer cried out, “Charge on Men!”41 Drummond owed his good fortune to his epaulettes, which were backed by a metal plate tucked into his pocket and had taken the force of the round that struck him.42

Baynes now divided his force into two groups. The main column, consisting of the 1st, 8th, 100th, and Newfoundlanders under Colonel Robert Young, advanced toward the naval dockyard using the shore road; a second group, commanded by Drummond, with the four companies of the 104th under Major Moodie, a company from the Glengarry Light Infantry, two companies of the Voltigeurs Canadiens under Major Frederick Heriot, and First Nations warriors, took a route that lay further inland to Young’s right. The two artillery pieces could not be unloaded from the merchantman, so artillery support was limited to fire from the gunboats and the schooner Beresford, whose captain ordered the use of sweeps to propel his vessel into the inlet.43

The movement of Drummond’s column was hampered by the close country and the abattis until his scouts located a path through the densely packed brush along which they could continue, clearing it of enemy stragglers. The Voltigeurs experienced similar difficulties, and were forced to move through the bush in sections. About an hour later, both columns reunited in line, with Young on the left and Drummond on the right. Before them were American troops arrayed in front of three barracks buildings that formed the main enemy position.44

After quickly surveying the American dispositions, Baynes ordered “an impromptu attack”45 against the barracks, but it was beaten back “with heavy loss.”46 By this time, Colonel Young, who had been ill when he embarked at Kingston, was unable to continue and returned to the landing site. Major Drummond, who was rallying the troops, then suffered a second wound, but continued leading his element. By now, support from the British gunboats ended when a rise in the ground masked their fire. Baynes was now in a difficult position: he faced a strong, entrenched enemy with clear fields of fire and artillery support, while his infantry were in the open with no artillery support; moreover, by this time, his force had been reduced to some three hundred men.47

Prevost now intervened and ordered a second attack. The right of the British line faced overwhelming fire and was rebuffed, but the troops on the left, who now included the 8th, 100th, and 104th Foot, cleared one of the barracks buildings. Lieutenant George Jobling from the Light Bobs made a dash for the American battery with half of the light company and promptly lost half of them. Another group of soldiers from the 104th momentarily took possession of one of the American field pieces. As Lieutenant Le Couteur, Major Moodie, and Private Cornelius Mills began turning a mortar they had taken on the blockhouse near Fort Tompkins, Mills was “slightly hit in five places”48 and Moodie was wounded. A dash by another group to cross the open space to the adjacent barracks was met by heavy fire, and more casualties were suffered. Among the wounded was Major Thomas Evans, commanding the companies from the 8th Foot. Another key officer, Captain Andrew Gray, the acting deputy quartermaster general for Upper and Lower Canada, who had helped plan the landings, was killed. Believing the outcome hung in the balance, Major Drummond obtained Prevost’s permission to take a message under a flag of truce to the Americans demanding their surrender, which they refused. Baynes, who had limited command experience, was uncertain about what to do next, and when he consulted Prevost, the commander-in-chief intervened a second and final time, ordering the force to withdraw and re-embark.49

It was the correct decision. The British attack force had been ashore for five hours, and while they had advanced inland over 1,200 yards nearly unmolested and were now at the last obstacle before the dockyard, their progress proved deceptive. Approximately 30 percent of the infantry were casualties and three of the key officers, Young, Evans, and Drummond, were unable to continue. Moreover, the attackers could not break through the main defensive position, where the protected defenders enjoyed artillery support, and many soldiers were running around aimlessly. The situation also seemed confused: to some it appeared that the Americans were fleeing from Fort Tompkins, while other witnesses believed the columns of dust near the village signalled the approach of enemy reinforcements. The bewildering state of the battle was so complete that, as the British order to withdraw was given, Lieutenant Wolcott Chauncey, the commodore’s brother, on the Fair American near Fort Volunteer, sensing that the dockyard was about to be overrun, raised a pre-arranged signal for American marines ashore to torch the storehouses and burn the new ship in the stocks.50

At this critical moment, Prevost directed his attention toward the stationary British squadron and the question of where the American fleet might be. If Chauncey’s squadron arrived, it would be disastrous — the combined British force might be captured in its entirety or intercepted as it returned to Kingston. In the event of a naval engagement, the British squadron would have difficulty manoeuvring against the trimmed enemy vessels, as the British decks would be filled with soldiers and equipment. At no time, however, did Yeo express any concern; rather, he left his squadron, and instead of supervising naval support for the operation, went ashore and was seen “running in front of and with our men … cheering our men on.”51 The result was that most of the squadron — and its powerful guns — remained several miles away and out of the battle; the only British vessels to participate in the battle were gunboats armed with a single 24-pounder carronade each and the 12-gun schooner Beresford, and they did so on the initiative of their commanders, not because of an express order from Yeo.

Fortunately, Prevost’s fears of a sudden appearance by Chauncey were never realized — in fact, the American commodore did not learn of the raid until May 30. He departed from the Niagara on the morning of May 31 and, upon arrival at Sackets Harbor, decided, after a period of “mature reflection,”52 to remain there to await the completion of the Pike, which would give him command of Lake Ontario. The new ship, which had emerged from the fire unscathed, would not be ready until mid-July, however, giving Yeo control of the lake for two months. Within days, Prevost exploited this turn of events by directing Yeo to deliver 220 men of the 8th Foot, along with much-needed supplies, to Vincent’s army at Burlington Bay.53

Although Prevost had been right to call off the action, this would have provided little comfort to the troops of the 104th. Le Couteur called the raid “a scandalously managed affair.”54 He had every right to be bitter. After being confined in the cramped spaces of the ships, boats, and bateaux for nearly two days, enduring rain, and then landing on enemy territory with no real idea of how far distant their objective lay, the four companies of the 104th “went into action admirably, formed and advanced as on a field day.”55 Enduring both friendly fire and heavy resistance from their opponents, they withdrew just as their objective appeared to be within reach.

West of the memorial to the 104th Foot (see page 162) is a memorial to the Crown Forces who fell during the Battle of Sackets Harbor. Twenty of the fifty names on the memorial are those of soldiers from the 104th Foot. Photograph by author

It comes as no surprise that, in contributing nearly a third of the men to the raid on Sackets Harbor, the 104th Foot also suffered the highest losses: seventy-eight dead, wounded, and missing, or nearly one-third of the total British and Canadian losses.56 Among the officer casualties were Major William Drummond, Captain Richard Leonard, Captain George Shore, Lieutenant Andrew Rainsford, Lieutenant James DeLancey — who would die from his wound on December 11 at Kingston — and Lieutenant Fowke Moore. Two sergeants, one corporal, and seventeen privates were killed outright and six men later died of wounds. It is estimated that another fifty-one men were wounded or missing. The raid was one of the costliest actions the British conducted in the northern theatre, and the casualties suffered were greater than those at Queenston Heights, York (losses to the regular troops only), Stoney Creek, Châteauguay, or Crysler’s Farm. Of the nine hundred men who sailed on May 27, forty-nine were killed in action, 195 wounded, and sixteen missing.57

The 104th Moves to the Niagara Peninsula

By late May, the Americans’ ambitious offensive plans to exploit their control of Lake Ontario by attacking York, Fort George in the Niagara Peninsula, and Kingston had begun to unfold. The campaign season had opened in April with their attack on York, which proved only partially successful. In May, the Americans landed in the Niagara Peninsula and, following the retreat of Brigadier-General Vincent’s Centre Division to Burlington Heights at the head of Lake Ontario, they took Fort George. However, with the lake now in British hands due to Chauncey’s decision to remain at Sackets Harbor, the plan to attack Kingston was put off. Moreover, Prevost was preparing to send Yeo, along with reinforcements and supplies, to join Vincent at Burlington Heights.58 As a result, the Niagara now became the principal theatre of operations.

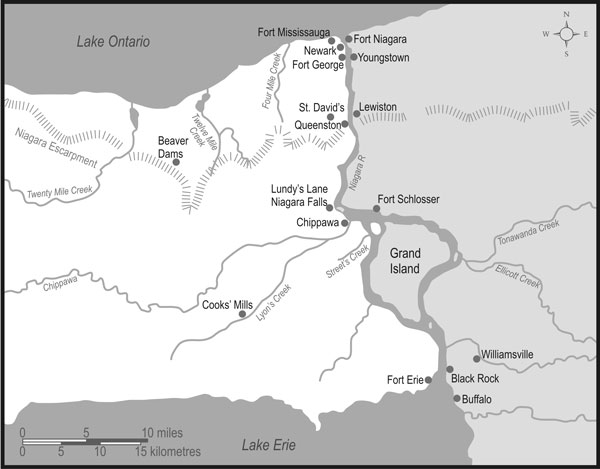

The strategically important Niagara Peninsula was one of the most fertile and heavily populated areas of Upper Canada. This rectangular block of land, about thirty miles wide and fifty miles long, is bounded by water on three sides: on the north by Lake Ontario, to the south by Lake Erie, and in the east by the Niagara River. The peninsula straddled the important communications route that connected the British supply line from Lake Ontario to Lake Erie. Soldiers, ordnance, supplies, and equipment were moved by boats using the Niagara River. The falls of Niagara and the gorge below it rendered that part of the river impassable, so a portage around the falls was established between Queenston and Chippawa. Fortifications were also placed near the source and mouth of the river, and at both ends of the portage. Fort George lay at the northeast end of the peninsula. More of a stockaded garrison site than a fort, this post also served as the British headquarters in the region. The town of Newark, also known at Niagara, at one time the capital of Upper Canada, was adjacent to the fort, and had a population of five hundred. Fort Erie was near the confluence of Lake Erie and the Niagara River. Built and rebuilt since the 1760s, it was in dilapidated condition when the war began. Minor fortifications mounting ordnance were also placed at both ends of the portage route.

In spring 1813, the American fixed defences along the Niagara Frontier included Fort Niagara, on the opposite side of the river from Fort George. Originally built by the French in the seventeenth century, the fort was transferred to Britain following the Seven Years’ War and later to the United States. About two miles upstream from the falls, at the end of the American portage around the falls, lay Fort Schlosser, and smaller battery positions and supply depots were established at other locations along the river as required.

The American occupation of Fort George and Newark had cut the British line of communication between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Unable to make use of the Niagara River, British forces in the Western District and Detroit found their supply situation worsened, as supplies and men now had to be transported from Lake Ontario across the Niagara Peninsula by cart and then reloaded onto vessels on Lake Erie. Outnumbered and with few defendable points between Fort George and Burlington Heights, British commanders considered completely evacuating the Niagara Peninsula, and perhaps moving as far as York should the US Navy regain ascendency on Lake Ontario. The British attempted to rebalance the situation by shifting units and supplies from Kingston to reinforce the 1,500 men currently serving in the Niagara. In the aftermath of Vincent’s withdrawal to Burlington Heights, the British began moving regular, fencible, and provincial units to the Niagara.

In early June, units along the St. Lawrence were hurried westward, including a detachment of the Canadian Fencibles that departed immediately for Burlington Bay. At Prescott, the Voltigeurs Canadiens, Glengarry Light Infantry, and the 100th Regiment were grouped into a brigade of light infantry and sent to Kingston.59 The flank companies of the 104th Regiment were brought up to a strength of sixty men each and, with a company from the Glengarry Light Infantry and detachments of the 8th and 49th Regiments, were also concentrated at Kingston, where they were to be “kept in perfect readiness to proceed from Kingston to the Head of the Lake.”60 On June 6, eleven bateaux were prepared to ferry these troops, along with ten days’ provisions, camp equipage, and all the militia clothing remaining in stores. Two days later, the gunboats Thunder and Black Snake were readied to escort the bateaux. On 8 June, the flank companies of the 104th Foot and a company from the Glengarry Light Infantry departed Kingston for Burlington Bay. Later that same afternoon, news arrived at Kingston of Vincent’s attack on the American camp at Stoney Creek and the Americans’ withdrawal toward Fort George.61

On June 11, the remainder of the 104th Foot, consisting of the four line companies under Major Moodie, were instructed to “proceed by water to join the forces under Brigadier General Vincent.”62 To bring them up to strength, “[a]ll of men of the 104th Regiment fit for field service” at Quebec were “to be sent forward to join the 1st and 2nd divisions of their regiment.”63 Furthermore, “all of the 104th Regiment fit for field service” from the two companies en route from New Brunswick to Quebec were to be “sent forward by detachments as they arrive.”64 On the morning of June 20, “all men of the [104th] fit for field service” and two companies of the 1st Foot under the command of Colonel Archibald Stewart embarked in bateaux for “the head of the Bay of Quinte, from thence they are to march at York, where they will receive further orders.”65 This detachment was delayed another two weeks, however, before they were finally loaded into bateaux for the journey to the Niagara Peninsula.

Among the staff at Kingston that oversaw the assembly of this large force of men, along with rations and equipment, as well as the collection of supplies for Vincent’s army and arrangements for the bateaux to transport them, was the newly promoted Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond, who was appointed acting deputy-quartermaster general to coordinate the great number of military, naval, commissariat, and civilian personnel needed for this large-scale movement to the Niagara. Personnel shortages required the militia to provide crews for the bateaux and their escorting gunboats, while gunners from the Royal Artillery were assigned to work the guns and a pilot was secured for navigation.66

The journey between Kingston and the Niagara Peninsula was difficult and dangerous. Not only were the men subject to the elements, including rain, wind, and cold, which weakened the men’s health and damaged their weapons and equipment, but they also faced threats from the enemy, whose warships were patrolling the lake. In most cases, the bateaux took the troops as far as York, from whence the journey continued on foot along poor roads that stretched around the head of the lake to Burlington Heights and continued along the south shore of the lake to the Niagara Peninsula. The soldiers of the 104th had already experienced long marches, however, and would have found this journey more pleasant than their trek from New Brunswick to Upper Canada, despite the potential threat they now faced from the enemy.

The movement of such a large number of “Troops and Stores up the Lake” was not missed by the Americans. In mid-June, Commodore Chauncey sent the schooner Lady of the Lake to “cruise close in with the enemy’s shore” west of Kingston and intercept any bateaux “passing up or down” the shoreline, while Major-General Henry Dearborn, the American commander in the northern theatre, reported the arrival of “about 500 men of the 104th regiment”67 to the Niagara Peninsula. On June 16, the American warship “captured the Schooner Lady Murray from Kingston bound to York with an Ensign and 15 non-commissioned officers and privates belonging to the 41st and 104th regiments, loaded with provisions, powder, Shot, and fixed ammunition.”68 Among the prisoners were the six-man crew of the schooner, an ensign and five privates from the 41st and nine privates from the 104th — William Drayton, John English, Henry Kane, Joseph Larencell, Thomas McGrierson, Malkam McKinsey, William G. Stewart, Joseph Wall, and Francis Xavier. The American patrol was resumed following the delivery of the prisoners to the naval base at Sackets Harbor, where they provided Chauncey with important intelligence on naval construction at Kingston.69

In response to the threat of the US Navy on the lake, the British undertook additional precautions to protect the bateaux convoys, including adding to the number of bateaux to increase the flow of troops to their destination. Regular troops, rather than militia, were now used to crew the bateaux, such as the “one sergeant and 12 men of the 104th Regiment” who were placed under the command of Captain Peter Chambers of the quartermaster general staff. Those selected for this arduous task were chosen from among “strong, healthy men who understand the management of boats.”70 An additional gunboat was also based at Gananoque to protect reinforcements moving from Prescott to Kingston. The continual shortage of manpower meant that desperate measures were necessary. Dr. Macaulay, a physician at Kingston, was instructed to select from the “convalescents of the 104th Regiment” men to join the gunboat patrol at Gananoque. Once at Gananoque, the men were to be issued with “arms, equipment, accoutrements and necessaries,”71 and then placed under the charge of Lieutenant Andrew Rainsford (spelled “Rangeworth” in the order), a son of the receiver general for New Brunswick, aboard the gunboat Retaliation.

The transfer of the 104th from Kingston to the Niagara Peninsula continued throughout the summer. In late June, “[o]ne captain, two subalterns, one sergeant and 11 privates embarked to join their regiment with the army under Brigadier-General Vincent.”72 The men received six days’ field rations for their journey. The captain in charge in all likelihood was Richard Leonard, the brigade major at Kingston, who had been released from his duties and allowed to return to the regiment. In early July, four bateaux carrying one officer, two sergeants, and twenty-two rank and file left Kingston to deliver stores to the Niagara. The 104th contributed one sergeant and eight soldiers to this duty, the rest being drawn from the 8th Foot. Upon arriving at their destination, these men would find that, although the British position in the Niagara had become more stable than in June, the situation was still serious.73

At his headquarters on Burlington Heights, Vincent approved a plan put forward by Lieutenant-Colonel John Harvey to attack the Americans at their recently established camp at nearby Stoney Creek, from where the enemy intended to descend on Burlington Heights. During an action on the night of June 5-6, seven hundred British troops confronted over three thousand Americans, captured their two generals, and left the defenders in disarray. On June 7, the Americans withdrew eastwards to Forty Mile Creek. By this time, Yeo had arrived and worked out a plan with Vincent to cut off the American force, but Dearborn, the American commander at Fort George, fearing this might occur, ordered his troops to withdraw to Fort George, a movement that was hastened by pressure from First Nations warriors, British infantry, and bombardment by Yeo’s squadron. By the second week of June, all American forces in the peninsula had withdrawn to Fort George.

Encouraged by these successes, the British commodore ranged around Lake Ontario, ferrying troops, bombarding shore installations, landing raiding parties, and even preparing for another assault on Sackets Harbor — although it was cancelled once surprise was lost — before anchoring off Kingston and ending his cruise in late June.74

This turn of events allowed Vincent to advance closer to Fort George, and in mid-June he moved his headquarters from Burlington Heights to The Forty (now Grimsby). From there, he established, under the overall command of Lieutenant-Colonel Cecil Bisshopp, a triangular network of forward outposts that harassed the enemy and ringed the American positions. Vincent selected Balls Falls at the mouth of Twenty Mile Creek as the headquarters for the advance force. His forces also reoccupied a large, two-storey house known as DeCou’s, seven miles to the southwest, that had been used as a depot for stores and ammunition and general rendezvous for troops prior to the capture of Fort George. A third outpost was established at Twelve Mile Creek (modern Port Weller) on the shore of Lake Ontario to the east of Bisshopp’s headquarters. These locations enjoyed good communications as they were linked by roads built on former First Nations trails extending westwards from Queenston and Newark. The three outposts were approximately seven miles apart, allowing them mutual support in an emergency.

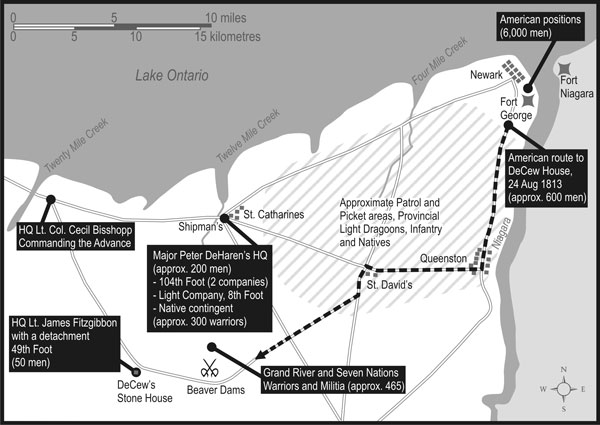

Vincent stationed the two hundred men from the flank companies of the 104th and the light company of the 8th Foot at the mouth of Twelve Mile Creek under the command of Major Peter V. De Haren of The Canadian Fencibles, and a light company of the 49th Foot under Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon at DeCou’s. An embodied troop of militia cavalry, The Provincial Light Dragoons, and eventually a troop of the 19th Light Dragoons, were also active in the area. First Nations warriors, whose confidence was restored by the victory at Stoney Creek, were based at Beaver Dams, just east of DeCou’s, with another detachment at Forty Mile Creek. They were soon joined by a reinforcement of nearly eight hundred tribesmen arranged by agents of the Indian Department from the Seven Nations around Montreal who arrived in the Niagara around the same time. Three hundred of the Caughnawaga (Kahnawake) warriors joined De Haren’s force at Twelve Mile Creek. Despite these new arrivals, Vincent was still outnumbered by the enemy, who occupied a fortified position.75

British patrols that penetrated as far as Fort George and even crossed the Niagara River helped to limit the reach of the American forces, reported on enemy activity, and harassed them whenever possible. On June 8, one patrol reported that the Americans were quickly withdrawing, and provided an estimate of their strength at Fort George. Whereas two days earlier Vincent had faced “3,500 men, 8 or 9 field pieces and 250 cavalry”76 at Stoney Creek, now that the Americans were withdrawing to Fort George, fresh reports indicated they had “4 to 5,000 men,” although many were considered to be “in a sickly condition.”77 These reports boosted Vincent’s confidence, and he believed that, with the cooperation of Commodore Yeo, he could “push forward and retake Fort George.”78 Unfortunately, the unresolved struggle to gain superiority on Lake Ontario made the commodore reluctant to commit his warships, and Vincent would have to continue with the blockade of the fort. Both armies also began raiding one another’s positions, often seizing supplies and food for their own use.

This semi-guerrilla war of patrols conducted between the British and American lines intensified as the weeks passed. In the course of one sharp skirmish, a detachment from the 104th light company was cut off from the main body of troops. Seeing the Americans through the trees, the Light Bobs set an ambush, and when the enemy responded by manoeuvring to surround them, they dashed into the woods and made their way back to their lines.

Over time, the Americans began to fix their attention on DeCou’s house, the base from which this aggressive patrolling originated and a lucrative depot filled with supplies. At Fort George, Major-General Dearborn and Brigadier-General John Parker Boyd agreed that the capture or destruction of that outpost would disperse the British and ease the harassment they faced from British patrols. They assigned this task to Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Boerstler and a force of six hundred men and two field pieces. Unfortunately, the Americans lost the element of surprise when, on June 21, two officers openly discussed the plan while dining at the home of James and Laura Secord in Queenston. With her husband still recovering from wounds he had received at Queenston Heights, Laura departed the next day to deliver this important information to the British. That evening, following an arduous seventeen-mile journey by foot, she reached DeCou’s, where she passed the details on to Lieutenant Fitzgibbon, who immediately sent out a party of First Nations warriors in search of Boerstler’s column and ordered the supplies and weapons stored at the house to be hidden.79

The deployment of British advance positions in the Niagara Peninsula in June 1813, and the movements of the US Army prior to the Battle of Beaver Dams. MB

Boerstler left Fort George on June 23 and halted overnight at Queenston. His column pressed on the next day, and at St. David’s the advance guard skirmished with warrior scouts. Just before 9:00 a.m., as they were nearing their objective, the Americans walked into an ambush at a point selected by Captain François Ducharme, the senior officer of the Indian Department present, and held by 465 Seven Nations and Grand River warriors and local militia. The initial volley created much disorder, but Boerstler regrouped his men and attempted to push through to DeCou’s. As the fighting erupted, Ducharme sent word to the other patrol bases to come to his aid.80

As the struggle continued, British reinforcements converged on Beaver Dams. Major De Haren immediately mustered both flank companies of the 104th and the light company from the 8th, and had them march southward to the sound of battle. As the column came within the sound of the musketry, De Haren ordered Lieutenant Le Couteur to ride forward to learn what he could. It took fifteen minutes for the young officer to reach the battlefield, where he immediately joined Fitzgibbon and his company from the 49th, which had just arrived. At the same time, a “flag of truce was sent in with an offer to surrender to a British force.”81

In the time it took the reinforcements to reach Beaver Dams, the struggle gradually had turned in favour of the First Nations forces, with the Americans suffering heavy casualties in a vain attempt to dislodge the warriors from their positions. They struck at the Americans repeatedly, and as noon approached Boerstler concluded that, with many of his men dead or wounded, the ammunition nearly expended, and his force surrounded, he was unable to continue the action or withdraw. With great reluctance, he sent forward a flag of truce offering to surrender. It was at this moment that the first reinforcements under Fitzgibbon arrived and, for reasons that are unclear, many of the Seven Nations warriors left the field.82

When the American artillery continued to fire on the redcoats, though ineffectively, Fitzgibbon attempted to convince Boerstler of the hopelessness of his situation by posting his men in plain view along the line of retreat, and then went forward to discuss terms with the American commander. Whatever reluctance Boerstler might have had in surrendering to the small force of British regulars present and whatever fears Fitzgibbon had that his ruse might fail ended when the companies belonging to the 8th and 104th arrived some twenty minutes later. De Haren “ratified the treaty which Fitzgibbon had entered”83 on behalf of Lieutenant-Colonel Bisshopp, and 512 American officers and men were taken into captivity. Another thirty men lay dead on the field and seventy were wounded. As the British troops maintained guard over the prisoners, De Haren placed Le Couteur in charge of Boerstler and the senior American officers. Later that day, as the 104th’s grenadier and light companies prepared to return to their patrol base, orders arrived instructing them to move to St. David’s, where they would be joined by the regiment’s four line companies, currently en route from Kingston. British forces were about to close in on the Americans occupying Fort George.84