The Blockade and Reconnaissance of

Fort George and Return to Kingston,

July-December 1813

Able to repel any force which the enemy may be able to bring against us.

— Kingston Gazette, October 9, 1813

In early July 1813, the British advanced their lines closer to Fort George following the First Nations’ victory at Beaver Dams. By this time, Major-General Francis de Rottenburg, the recently appointed commander of Upper Canada, had arrived in the Niagara Peninsula and assumed control of operations. He had determined that the uncertain naval situation on Lake Ontario and the stalemate around Fort George warranted increasing the garrison of the stronghold at Burlington Heights against a coup de main, while pickets maintained watch over the fort.1

De Rottenburg complained to Lieutenant-General Prevost that “everything is unhinged” in Upper Canada. Disappointed that lack of cooperation from the Navy — had it been provided, he claimed, “Fort George would have fallen” — now forced him to establish a blockade of the fort, which would require many more men. The needed reinforcements from Kingston, including the “104th[,] are not yet arrived” due to the poor condition of the roads, “the worst” de Rottenburg “ever saw anywhere.”2

Nonetheless, fortune smiled on the British, and de Rottenburg was able to tighten the noose around the American foothold on the peninsula. A blockade of the mouth of the Niagara River and the capture of merchant vessels by the naval squadron under Commodore Yeo, and raids against supply depots along the Niagara River and the south shore of Lake Ontario by naval personnel, British and Canadian troops, and First Nations warriors left the Americans under Major-General Dearborn relying on a tenuous line of communication to Buffalo. A probe of the American lines at Fort George on July 8 by British troops and warriors led to a vicious skirmish that allowed the British to extend their blockade close to the village of Newark, and British patrols continually harassed the defenders.3

Following the conclusion of the encounter at Beaver Dams, the grenadier and light companies of the 104th relocated to St. David’s, where de Rottenburg had moved his headquarters. The arrival of reinforcements, including the 104th’s line companies, still left him with too few men to lay siege to Fort George, but de Rottenburg believed his force strong enough to blockade the Americans and reduce “the enemy to the ground he stands upon, and prevent his getting any supplies from our territory.”4 Occupation of the new positions commenced on July 17.

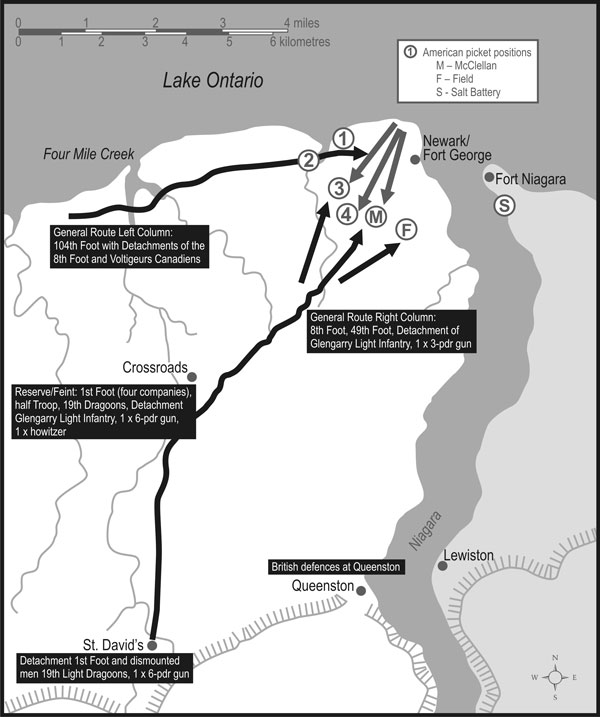

The blockade extended from the mouth of Four Mile Creek, south to St. David’s, and then east to the Niagara River. The Lake Road, running from Stoney Creek to Newark, ran parallel to the shoreline, and was intersected by the Black Swamp Road near Newark, which ran south, crossing Two and Four Mile Creeks. The bridges over the creeks on both roads were protected by fieldworks. The blockade was maintained using units posted well forward. The British left, commanded by Colonel Robert Young, rested on Servos’s Mills, near the mouth of Four Mile Creek, where there was a secure shelter for the supply boats. The artillery was also located here and supported by the two flank and four line companies of the 104th under the command of Major Moodie. Pickets, each between twenty-four and sixty men strong, were established nearly a mile in advance on the Lake Road. The centre, consisting of the 8th Foot, a detachment of the 100th, and all of the warriors, under Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Battersby, was based on the Swamp Road where it crossed Four Mile Creek, with pickets thrown out at Ball’s farm. The 1st Foot and the Glengarry Light Infantry held the ground between St. David’s and Queenston, placing their pickets well forward. A strong observation post was also established on Queenston Heights. Unfortunately for Major Drummond, who had just arrived in the Niagara and was to have taken command of a force of light infantry, orders sent him back to Kingston, from where he would take command of the garrison at Gananoque.5

Across from the British positions, Dearborn had departed, and Brigadier-General John Parker Boyd was appointed to temporary command of Fort George. He found himself in a difficult position. All was not well within the fort: many of the five-thousand-man division were recent recruits, and foul weather, “having been extremely unfavourable to health,”6 brought widespread illness, leaving a thousand men unfit, and causing Boyd to consider withdrawing his men to Fort Niagara — although, because the naval issue on Lake Ontario remained unresolved, such a plan could not be executed. Given these circumstances, in early July Boyd was instructed to “pay the utmost attention to instruction and discipline of the troops, and engage in no affair with the enemy, that can be avoided.”7

The division Boyd commanded consisted of a large detachment of artillery, a regiment of light dragoons, a regiment of riflemen, ten regiments of infantry, and warriors. Since early June, they had been busy erecting fieldworks and placing artillery in battery positions. Records are unclear as to the total ordnance mounted in the defences, but it might have included six 18-pounders and “about” fifteen 6-pounder field pieces. The Americans positioned their outposts around the perimeter of farm houses running along Two Mile Creek. From the north, these outposts were identified as: “Crooks” (No. 1), “Secord” (No. 2), “John Butler” (No. 3), “Thomas Butler” (No. 4), “McClellan” (No. 5), and “Fields” (No. 6).8

British raids in July against Fort Schlosser, located across the Niagara River from Chippawa, and Black Rock, near Buffalo, helped to isolate Boyd’s command, and his only support now came from across the river at Fort Niagara. Despite receiving instructions not to attack the British, Boyd did not remain complacent. In late July, he arranged with Commodore Chauncey an amphibious attack against Burlington Heights to compromise de Rottenburg’s line of communication. The force, five hundred men from Fort George, was unable to negotiate the heights, however, and re-embarked on Chauncey’s warships. The Americans then headed for York, where they secured a large quantity of supplies, before returning to Fort George and continuing to improve the works. A similar operation, planned to take place a few days later, was called off because of unfavourable winds. Boyd’s confidence improved in August with the arrival of reinforcements that allowed him to reinforce his outposts, which were now facing daily attacks from the British and Canadian forces and their First Nations allies.9

In this war of outposts, the two sides tested the mettle of their opponents. Day and nighttime raids became the norm, wearing out the men, as they were almost continually under arms or called out by nearly endless alarms. Losses also mounted. In one incident on July 17, elements drawn from the 8th, 49th, 104th, and the Glengarry Light Infantry advanced to the intersection of the Black Swamp Road and the Four Mile Creek Road, known as the “Crossroads” (now Virgil, Ontario), where, in a sharp skirmish, they succeeded in driving back an American picket. The next day, American riflemen, supported by Oneida warriors, attacked the advance picket, killing two men and wounding five others. The artillery often supported these attacks or conducted its own harassing fire against the enemy.

In July, de Rottenburg complained about the increasing rate of desertion in the Centre Division, which was a “growing evil in this army.”10 One sergeant from the 104th, Thomas Chase, deserted, no doubt due to “cowardice,”11 as Lieutenant John Le Couteur saw it.12 Desertion, the absenting of a member of the regular army without permission, was a serious crime in the British Army that, upon conviction, was punishable by death or other punishment “as may be inflicted.”13 Increasingly, however, as the war continued, the need to preserve manpower brought a decline in the use of capital punishment, and soldiers convicted of desertion were often returned to the ranks. Although desertion received scant attention in official papers, it was a leadership challenge that all officers and NCOs dealt with at one time or another. The reasons a soldier would abandon the Army were complicated, and could be attributed to low morale and the conditions of service, including lack of pay, poor lodging, inadequate rations, and strict discipline, as well as the effects of combat and physical discomfort caused by climatic conditions.

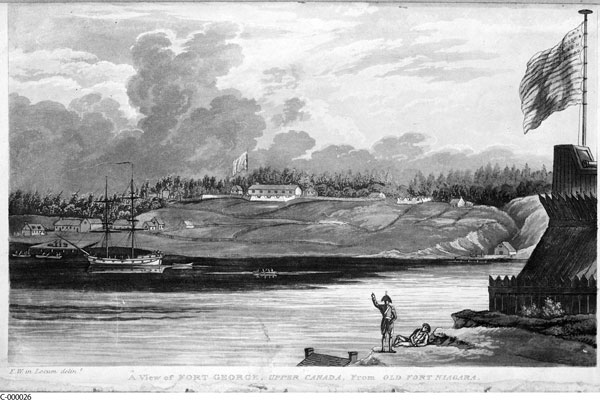

During the summer and autumn of 1813, the 104th Foot participated in the blockade of American-occupied Fort George; in August, it took part in the reconnaissance of the defences, coming within visual sight of the fort. The following summer, the grenadier and light companies marched past the ruins of Fort George as they advanced south to meet the Americans at Lundy’s Lane. (LAC C-000026)

The rate of desertion in regular units serving in British North America during the War of 1812 was the second highest the British Army faced anywhere during the Napoleonic Wars. The desertion rate between 1812 and 1815 amounted to four men per thousand, accounting for two thousand five hundred men. This situation mirrored British experience during the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolutionary War, when desertion rates were higher in North America than in any other theatre. This was because the largely English-speaking colonies provided a society that was easier for a deserter to meld into and offered them a new life. It should not come as a surprise, then, that many units raised in British North America, including fencible and provincial regiments, experienced a high rate of desertion; the 104th alone lost forty men from this cause during its stay in the Niagara in 1813.14

Major James Fulton, an aide-de-camp to Prevost, noted that the desertions “from this Army” in the Niagara “lately have been very great.” He cited “no less a number than fifteen men from the 104th Regt” as having deserted, six of whom came from the flank companies. Fulton explained that, in consequence of “the shameful conduct of this Corps [the 104th],” the 1st Foot had to “relieve them”15 of some of their duties. To put an end to this disturbing trend, de Rottenburg made an example of five men belonging to the 104th who had abandoned their posts at St. David’s and headed for the enemy’s lines, only to be apprehended when they decided to return. At a general court martial at de Rottenburg’s headquarters at Twelve Mile Creek, all of them, as well as another soldier from the 1st Foot, were found guilty. Prevost confirmed the finding, but decided to show clemency. On July 21, only two privates from the 104th, James Bombard and John Wilson, and the man from the 1st Foot were “shot for examples sake.” The others — Privates William Jackson, Daniel Lee, and Sawyer Ruby16 — were conditionally pardoned and transported for life to Australia. Unfortunately, the problem would persist into the autumn as the inclement weather worsened morale.17

In August, changing circumstances caused Prevost once again to consider attacking Fort George. By this time, the British had 2,800 men surrounding the fort and nearby Newark, but still faced almost twice as many Americans. On August 21, Prevost reached the British lines, his visit prompted by the worsening situation on Lake Erie and at Detroit, where reinforcements and supplies were desperately needed. Since he had taken command of his flagship Queen Charlotte at Amherstburg, Commander Robert Barclay had struggled to obtain materiel to outfit his squadron and sufficient seamen to complete his crews. Prevost, anxious to re-establish the flow of supplies to both Barclay and Major-General Henry Procter, the commander of the Right Division of the Army of Upper Canada, wanted to eject the enemy from Fort George in order to free up troops to reinforce Procter and provide manpower for the Lake Erie squadron. Before he ordered a general assault, however, Prevost deemed it necessary to determine the extent of the “enemy’s position and strength,”18 and ordered a reconnaissance of the enemy’s defences.19

Prevost appointed de Rottenburg overall commander of the operation, while Brigadier-General Vincent would oversee its execution. The brigade under Colonel Robert Young, which held the line along the Four Mile Creek, would form “two columns of equal strength”20 of approximately a thousand men each. The left column, consisting “principally of light troops” of the 8th and 104th Foot and companies from the Voltigeurs Canadiens under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel James Ogilvie, was to move eastward along the shoreline and then “surprise and cut off”21 the enemy’s pickets on Two Mile Creek at the outposts identified as “Crooks” and “Secord” (Nos. 1 and 2). To their south, the second column, consisting of a demi-brigade commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Battersby, with his 8th Foot, and the 49th Foot commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Plenderleath, with one 3-pounder gun, would advance northeast of St. David’s and attack the four pickets on Four Mile Creek at outposts “John Butler” (No. 3), “Thomas Butler” (No. 4), “McClellan” (No. 5), and “Field” (No. 6). Dismounted light dragoons and four companies of the 1st Foot would support the attack by feigning movement against the McClellan picket. A reserve of sixty men and one gun stood ready to guard the post at St. David’s, while another detachment guarded Queenston. First Nations warriors were to participate as well. Both columns would attack simultaneously, with the “commencement of a heavy fire”22 being the signal to advance.

At daybreak on August 24, a barrage announced the opening of the attack. Joining Ogilvie’s column on the left were 326 men from the 104th commanded by Major Moodie, a detachment of Ogilvie’s 8th Foot, and three companies of the Voltigeurs Canadiens under Major Frederick Heriot. Instructed to move carefully under cover as they approached their two objectives, Moodie “was hotly pressing the American picquets,” when Le Couteur arrived with instructions from Prevost, who was observing the attack, only to feel out the pickets and “not to expose Himself”23 to the enemy’s guns at Fort George. For his part, Moodie was upset with the limited scope of the attack. Having cleared one picket and the enemy from the nearby woods and gone forward with Colour Sergeant Benoni Avery24 and bayoneted an American sentry, Moodie felt that, given the ease with which the pickets fell and the occupation of a portion of Newark, the “defence was quite feeble” and “the place [Fort George] could be taken by a coup de main.”25

The notion that the reconnaissance made by British, Canadian, and First Nations warriors was sufficient to have taken the fort and avoided the destruction of Newark in December has made its way into the literature of the War of 1812. British officers had carefully surveyed the main defences, however, and determined that a complicated plan, requiring a battering train of artillery and the cooperation of Yeo’s squadron, would be needed to take the fort. In addition, a second attack would have to be directed simultaneously against Fort Niagara, across the Niagara River and within supporting range of Fort George. As well, Yeo was unwilling to expose his squadron until Chauncey had been defeated. In late August, Prevost studied the American defences from the deck of one of Yeo’s warships and, once again, concluded that a successful attack on Fort George was impossible until the British had secured naval control of Lake Ontario. At the cost of several men killed and wounded, the reconnaissance revealed that Fort George could not be taken under existing conditions, and the British continued with an “economy-of-force” operation to contain a large American army on an insignificant part of British soil to prevent its being employed elsewhere.26

The 104th’s reconnaissance of Fort George cost the regiment Privates Edward Mitchell and John Thom, both from Lower Canada, killed; and Privates James Nicholson and John Reed captured. As well, on August 28, Private William Garths, a veteran of The New Brunswick Fencibles, died of wounds received in the attack. On August 25, the 104th reported an “effective strength” — those men present for duty — of 156 men, a considerable reduction from the 422 rank and file who were available in June. The remaining men were “on command” — that is, employed away from the unit.27

By the end of the summer, more than 3,200 British troops were distributed among two brigades and three smaller commands between Burlington Heights and the Niagara River. As impressive as these forces appeared, however, the approach of autumn and the cooler, damp weather worsened the conditions for the men living in the open, and the spread of disease reduced their numbers. By mid-September, 525 men were reported as sick, and with more men succumbing to disease every day, de Rottenburg secured permission to move the Centre Division to a healthier location at Burlington Bay.

Then, after learning of the shift of American troops from Fort George to Sackets Harbor, which indicated that the next likely threatened point would be the important naval base and logistical installation at Kingston, de Rottenburg began moving a considerable portion of his force there. Before heading to Kingston himself in early October, he left instructions for Major-General Vincent to concentrate the remainder of the forces in the Niagara Peninsula against Fort George and to be ready to withdraw to Burlington Heights should he be threatened by Americans advancing from the Western District of Upper Canada.28

Learning of their pending departure from the Niagara, the officers and men of the 104th “thoroughly rejoiced.”29 It’s possible none were happier than the 251 men occupying the pickets between Four Mile Creek, and the “pestiferous and noisome marsh”30 of the Black Swamp between Six and Eight Mile Creeks. Other detachments of the 104th were farther west and included 3 men at St. David’s, 65 between Ten and Twelve Mile Creeks, and, at another post, located between Ten and Twelve Mile Creeks and commanded by Lieutenant Andrew Playfair, were 26 of men from his company and 2 members of The Provincial Light Dragoons. Another 46 men were at Burlington Heights. The poor weather contributed to lowering the men’s morale, leading to another 20 desertions during September. As well, in mid-September, 62 of the 391 men present were reported as sick and another 79 were absent.31

In early October, the 104th, 49th, and three companies from the Voltigeurs Canadiens departed the Niagara for Burlington Bay, where they embarked on boats for York. Moving quickly out of Burlington Bay on October 3, the flotilla sailed through the line of warships of the Royal Navy squadron commanded by Yeo that had anchored there on September 28 following a sharp engagement with the Americans. The squadron had just completed repairs and was about to sail. From their bateaux, the soldiers of the 104th and their comrades gave the sailors “three Jolly cheers”; the sailors returned the compliment by manning the yards.32 Made wet and miserable during their voyage by the rain and high waves that crashed into the bateaux, and often out of sight of the other boats, thirty men of the 104th reached Kingston in the early afternoon of October 7, with the remainder of the convoy arriving the following day.33

The arrival of these reinforcements, amounting to nearly eleven hundred men, was welcome news to the citizens of Kingston and was reported in the local newspaper:

We are happy to announce the arrival of Lt. Col. Drummond with the first detachment of the 104th Regiment from Burlington Heights. This Regiment with the 49th and the corps of Voltigeurs may be expected here in the course of to-day or to-morrow. These three gallant Regiments together with our brave Militia who are pouring in from all quarters and have already assembled in considerable numbers will be a sufficient reinforcement and with our present respectable garrison will be able to repel any force which the enemy may be able to bring against us.34

The 104th now joined the Left Division, a geographical command responsible for the defence of the important line of communication that extended from Kingston to Montreal and commanded by Major-General de Rottenburg, lately replaced as commander of Upper Canada by Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond.35

Meanwhile, fears that Kingston would be attacked proved unfounded, as the Americans instead began their largest offensive of the war, against Montreal. In October, a four-thousand-strong division under Major-General Wade Hampton invaded Lower Canada from eastern New York, followed by an army of seven thousand three hundred men under Major-General James Wilkinson that proceeded down the St. Lawrence River. Hampton posed the most direct threat to Montreal, but on October 26, 1,770 Canadian soldiers and warriors under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Charles de Salaberry defeated the Americans at the Châteauguay River, causing Hampton to withdraw back across the border.36

Attention then shifted to Wilkinson’s army advancing on Montreal. Based on Prevost’s earlier orders, six hundred men under Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Morrison left Kingston to pursue Wilkinson, while Yeo detached two schooners and seven gunboats under Captain William Mulcaster in support. Wilkinson’s advance by boat down the upper St. Lawrence was slowed by British and Canadian troops, who enjoyed good intelligence and communications, while his logistical situation only worsened. The campaign ended in November following the British victory at Crysler’s Farm, 18 miles west of Cornwall. With the rear of his column hounded by British troops, his rations running low, and facing a large garrison defending Montreal, the strength of which was “equal, if not greater than our own,”37 Wilkinson went into winter quarters at French Mills, now Fort Covington, New York, ending the last major enemy offensive of the year.38

During this crisis, the 104th Foot contributed to the defence of the Kingston area. Most of the regiment was concentrated in Kingston, with a detachment under Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond at Gananoque. In late October, American intentions were still unclear, and the garrison of Kingston was subject to many alarms, all of which proved false. Then, on November 7, as the 328 boats carrying Wilkinson’s army came into view on the St. Lawrence River at Prescott, Brigadier-General Duncan Darroch at Kingston ordered the light company of the 104th to the spot. The Light Bobs reached their destination in just a few hours, only to be told to return to Kingston.39

The abandonment of the American offensive ended the campaign season and the troops moved into winter quarters. Attention now turned to the more agreeable tasks of rest and recuperation and a much-needed opportunity to bring in replacement personnel and replace kit and necessaries. The soldiers looked forward to the opportunity of spending some of the pay owed to them in arrears in happier pursuits than could be obtained from the suttlers and in the taverns. The officers enjoyed the more pleasant aspects of civil society, including balls, dinners, and mixing with the fairer sex. In the meantime, training also began as the regiment drilled on the ice of the frozen harbour.

In November, the officers and soldiers became “entitled to share in the captures made by the Centre Division upon the Niagara Frontier in the Summer of 1813.”40 Payment of the shares of prize money provided a welcome supplement to their income. As in the Royal Navy, Army practice was to offer cash payouts to the troops for all public property they had had a hand in taking. The funds paid were determined by the assessed value of the materiel or goods captured, and were distributed in shares based on the recipient’s rank. The thirty shares that Major Moodie, the senior officer present from the 104th, was entitled to resulted in a payout of £9 7s and 6d. Each captain received £5 7s 6d, while lieutenants received £2 10s 6d, sergeants 12s 6d, and corporals 9s 4½d. Lewis Lock, a private man, received a single share of 6s 3d, more than six days’ wages.41 The £200 15s 7½d in prize money Noah Freer, the prize agent to the Army in the Canadas, allocated to the 104th was divided by regulations into 642½ shares to allow its proper distribution to the twenty-two officers, twenty-nine sergeants, twenty-nine corporals, fourteen buglers, and 297 private men eligible. Unfortunately for volunteer gentleman John Winslow, his status meant that no prize money could be granted to him.42

The end of the year also brought some personnel changes to the 104th Foot. During 1812, British authorities had augmented the defences of New Brunswick with another fencible regiment. When this news reached Upper Canada, a handful of the serving officers, NCOs, and men from the 104th requested transfers to the newly raised New Brunswick Regiment of Fencible Infantry. Among them was Robert Moodie, whose application to be the commanding officer found favour with Prevost. In early 1814, Moodie, who had been in the Army since 1795, handed command of the 104th over to Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond and departed to take up his new command at Fredericton. Joining Moodie was Colour Sergeant Peter Smith,43 who had commenced his service in 1804 as a private in the old New Brunswick Fencibles and who was now appointed an ensign, a rare distinction for this period.44

As the officers and men of the 104th Foot settled into winter quarters, they likely took stock of their experiences since arriving in Upper Canada that spring. In six months of active campaigning, four companies had participated in the amphibious assault on Sackets Harbor, followed by the transfer of all six companies stationed at Kingston to the Niagara Peninsula, where they occupied the forward defences, participated in the closing stages of the action at Beaver Dams, and then took part in the blockade of Fort George. In that time, they had lost fifty-two men dead from all causes and a number of wounded. At least forty men had also deserted during the year. As they reminisced about these events, their thoughts likely turned to the coming spring and what the new campaign season would bring.45