Kingston, the Upper St. Lawrence River,

and the Flank Companies on Detached Service in the Niagara Peninsula,

January-December 1814

[E]verything that could be required in a soldier.

— Surgeon William Dunlop

In early 1814, William Drummond discovered that, despite his appointment as commanding officer of the 104th Foot, Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond, the commander of Upper Canada, had other plans for him. In April, while Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond was still the acting deputy quartermaster general, General Drummond sent him to Fort George to assist the newly arrived commander of the Right Division, Major-General Phineas Riall, in ensuring “matters” within his command “assume an aspect of more promise than they have hitherto done as far as regards the Works of Defence ordered to be erected upon that line.”1

As was the case with other competent senior officers serving on the staff, Drummond also received an opportunity for further field command, and in March 1814, following the British defeat at Longwoods in the Western District of Upper Canada, he was “entrusted with the command of the force advanced towards the mouth of the Thames”2 that was to oppose the Americans should they continue their advance eastward. Instead, the enemy withdrew to Detroit, and Drummond returned to his duties in the Niagara, where, in early May, he learned he was to return to Kingston. He undoubtedly was pleased with the publication of the General Order on May 9, 1814, stating that, upon his “delivering over the charge of the [quartermaster general’s] department” to Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Myers, recently paroled from having been a prisoner of war, he was, finally, to “assume command of the 104th Regiment.”3

Drummond found the sickness that had plagued the regiment during the winter had reduced it to the point where it was “so much afflicted by the intermittent fever as to be extremely ineffective.”4 The 104th was well below strength, numbering just 384 men in April. Recruiting parties that had been sent to Montreal during the winter under Captain Andrew Rainsford found only seven men to serve in the ranks. In late June, believing the root of most of the illness was the damp and miserable conditions at Kingston, Drummond secured approval to move the 104th to Fort Wellington, at Prescott, and “select[ed] from it a detachment of the most effective for Cornwall.”5

Drummond also continued with the intensive program of training he had initiated earlier in the year. His goal was to prepare his men for the rigours of fighting in the wooded terrain of Upper Canada. As Lieutenant John Le Couteur recalled, the day began early: “Up at five for a Muster. Our Colonel is an early bird with a Vengeance.”6 Drummond “amused Himself,” Le Couteur noted, “by teaching us to load on our backs,” drill that the light company “did not at all enjoy scratching their nice bright pouches and dirtying their Jackets.”7 At the end of June, the regiment was inspected by Major-General Richard Stovin, commander of the Centre Division, followed by a review of all regimental books, barracks, and kit.8

In addition to their training, on June 4 the men also found reason to celebrate when they observed King George’s seventy-sixth birthday. The officers and men also rejoiced when the “great and glorious intelligence [was] received of the dethroning of Bonaparte and the restoration of the Bourbons to the throne.”9 Hopes now grew that, with the war in Europe over, reinforcements would be sent quickly to join the troops in North America and end the war there.

During the spring, Lieutenant-General Prevost, Lieutenant-General Drummond, and Commodore Yeo considered a number of schemes for attacking enemy installations. One proposal was to assault the American naval base at Sackets Harbor with a much larger contingent than had been used in 1813. Of the three thousand troops selected to take part, the 104th was to have contributed two hundred and fifty, but the plan was never approved. Instead, in May, nine hundred soldiers and Royal Marines drawn from the Kingston garrison attacked the American supply depot at Oswego, an operation in which the 104th did not take part.10

The 104th did play a brief role, however, in the struggle for naval supremacy on Lake Ontario. In March, construction began at the naval dockyard of a new warship that would “look down all opposition.”11 Once launched, the first-rate warship would be the largest naval vessel to serve on the Great Lakes. Assembling all the material needed to complete the new warship placed a great strain on the upper St. Lawrence supply line, and this delayed the delivery of necessary equipment and postponed the launch date from early summer to September. As well, insufficient personnel were available to sort through the tons of stores arriving at Kingston and to build the new ship. More men accordingly were hired for the task, and units from the Kingston garrison joined in the work. In mid-June, the “whole of the” 104th Foot was ordered to “work at the new Line-of-Battle Ship, 104 guns.” Unfortunately for the regiment, musings that, “in compliment to our number of course she sh[oul]d be called the 104th,”12 never transpired; instead, the ship was commissioned that autumn as HMS St. Lawrence.13

As these activities continued into July, reinforcements steadily flowed into Kingston. On July 6, news arrived that the Americans had struck again in the Niagara Peninsula, this time sending a division under Major-General Jacob Brown across the Niagara River against Fort Erie. The next day, part of the 89th Foot, which had just returned to Kingston, was sent to York, while other units in Kingston prepared to reinforce British troops in the Niagara Peninsula. On July 9, Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond was informed that the flank companies of the 104th were to concentrate at Kingston and then embark in bateaux, destined once again for the Niagara.14 The remainder of the regiment was to be sent to Fort Wellington as planned.15

Earlier in the summer, the British had received evidence of a build-up of American troops near Buffalo. Lieutenant-General Drummond decided the large concentration indicated that he would be facing the main American offensive of 1814. As Prevost read these reports and began sending reinforcements to Drummond, he expressed concern about whether it would be possible to provide enough supplies while the Americans controlled Lake Ontario. By the early summer, the British had four thousand men deployed as the Right Division, under Major-General Phineas Riall, between York and Fort Erie. Reports indicated the Americans had amassed four thousand five hundred men, ironically styled the Left Division of the Army of the United States, under Major-General Jacob Brown. Riall proposed leaving garrisons at Forts George and Niagara and concentrating the balance of his troops in a field force that would meet the Americans in the open. The flaw in this assessment was that Drummond and Riall believed they would face poor-quality troops similar to those encountered during the previous winter. The first encounter, at Chippawa in July, revealed, however, that Brown’s troops were well trained and that the Right Division would require reinforcements. Prevost’s fears regarding his ability to provide adequate support to Drummond quickly became reality.16

On July 10, Drummond advised Prevost of Riall’s defeat at Chippawa and of the reinforcements he was sending to the Niagara. The 6th and 89th were on their way to York, and he had placed the “two flank companies of the 104th, completed to 60 men each, under Lieut. Colonel Drummond, for the purpose of acting with the Indians in that direction.”17 As in the summer of 1813, Kingston was denuded of troops and supplies as the regular regiments departed, accompanied by the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles, the Incorporated Militia of Upper Canada, and the Regiment de Watteville, until the 104th became the only regular unit left there. The other units “were pushed on”18 by boat or overland march to an assembly area at Burlington, where they were to be met by Lieutenant-General Drummond, who was planning to assume command of the army in the Niagara Peninsula. Following three days’ rest at York, the reinforcements’ journey continued to Burlington Bay, where a final check was made of their health and the serviceability of their equipment before they were sent on to the Niagara Peninsula.19 The flank companies of the 104th commanded by Captains Richard Leonard and George Shore were part of this move, but only as far as York, where Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Morrison, commanding officer of the 89th Foot, ordered them to halt. On July 20, Riall requested Drummond to order the “flank companies detained at York” and the 89th to “be pushed forward with all despatch.”20 These movements reduced the size of the Kingston garrison, and in a short time the line companies of the 104th became the only regulars left there.

Meanwhile, the American campaign plan had fallen apart. Learning that Commodore Chauncey was ill and unwilling to cooperate with his division, Major-General Brown developed a new plan. Beginning on July 20, Brown tried to coax the garrison of Fort George into the open or to lure Riall, who had withdrawn the remainder of his force to the west, into a general action. Neither scheme worked. Two days later, Brown ordered his division back to Queenston to consider his options. Early on July 24, he concluded that the supply state of his division would be improved by shortening his line of communication from Buffalo, and ordered his men to break camp and move to Chippawa.21

That evening, Lieutenant-General Drummond arrived at York. Based on intelligence given him by Riall, he planned to make use of the fresh units now gathered there to attack an American battery being erected at Youngstown, to the south of Fort Niagara, which was thought to threaten Fort George. With British naval forces under Yeo now in command of Lake Ontario, on July 23 Drummond instructed the four hundred-strong 89th Foot to proceed to Fort Niagara — which the British had occupied in December — in two ships, with Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond and the one hundred and twenty men of the 104th to follow the next day.22

The attack on the American battery was scheduled to take place on July 25. Fifteen hundred men, divided between two forces and a naval contingent, were to advance south along each bank of the Niagara River. On the Canadian side, Lieutenant-Colonel Morrison would threaten Queenston with his 89th Foot, while Lieutenant-Colonel John Tucker, the commander at Fort Niagara, would proceed along the American bank of the river and then attack the enemy battery thought to be near Youngstown. Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond and the flank companies of the 104th were attached to Tucker’s command, which also included three hundred men from the 41st, two hundred from the 1st Foot, and a contingent of First Nations warriors.23 Before the operation began, Lieutenant-General Drummond decided to “ascertain the accuracy of the intelligence respecting the enemy’s force and of his preparations on the [American] side of the river.”24 In the meantime, instead of joining Tucker’s advance, the 104th’s Drummond was assigned to the reconnaissance of the Canadian side of the river, while the flank companies of the 104th were allocated to a brigade in Riall’s Right Division.25

On July 24, two reconnaissance parties left Fort George to learn more of the enemy’s disposition. Drummond and First Nations leader Captain John Norton led one party, while a detachment of The Provincial Light Dragoons commanded by Captain William H. Merritt made up the other. By this time, the American Left Division had broken camp and was retiring on Chippawa. At St. David’s, Norton learned of the withdrawal from a deserter and immediately sent a messenger with this information to Riall, which set in motion a new series of moves.26

Riall had reorganized his scattered command into two main forces, each with a mix of regular, fencible, and embodied militia commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Hercules Scott and Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Pearson, and a reserve based on the 1st Foot. Upon learning about the American withdrawal, Riall ordered Pearson with 1,200 men to maintain contact with the Americans. Meanwhile, at Fort Niagara, Tucker also informed Lieutenant-General Drummond, who had just arrived from York that morning, of the American withdrawal to Queenston. Drummond ordered Tucker to continue with the attack on the Youngstown battery, while he would accompany Morrison on his advance along the Canadian bank of the river. Tucker’s men quickly cleared the Americans’ battery, and his mission completed, he was instructed to return to Fort Niagara. Meanwhile, Drummond and Morrison halted at Queenston, where Drummond told Riall to bring up Scott’s force.27

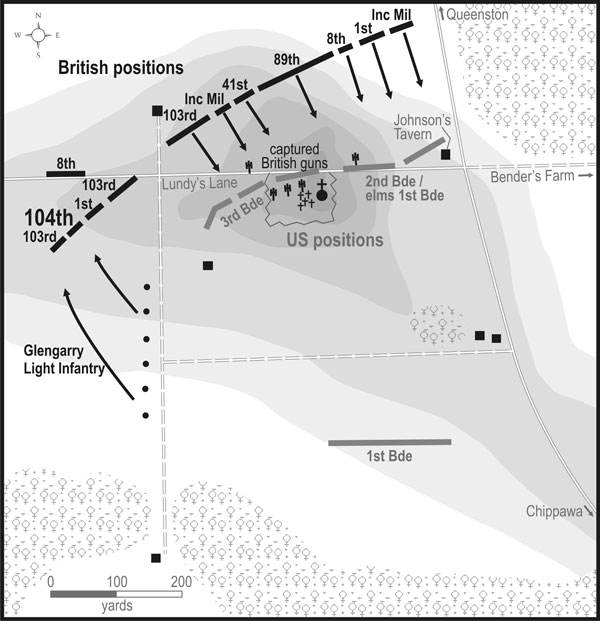

Scott received Riall’s message at his camp at Twelve Mile Creek. Anticipating that a move would take place that day, Scott had had his men ready since 3:00 a.m., but, as nothing had happened, he let his men rest. Among the recent arrivals at Twelve Mile Creek was Captain Richard Leonard, in overall command of the 120 men of the two flank companies of the 104th. His own Grenadier Company and Captain George Shore’s Light Company were assigned to Scott’s 1st Brigade, which also included the 8th Foot under Major Thomas Evans, the 103rd commanded by Major William Smelt, and three 6-pounder brass guns, with forty personnel, commanded by Captain James Mackonochie. In reserve were the four-hundred-strong 1st Foot and the 2nd Militia Brigade commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Hamilton that included men drawn from five militia regiments. With orders to move in hand, the column of troops immediately marched to join Lieutenant-General Drummond.

The day had grown quite warm by the time Scott’s force set off from Twelve Mile Creek, and the troops kicked up clouds of dust as they marched. Their route took them by way of Beaver Dams toward Lundy’s Lane, a road leading east to the Niagara River. When they were three miles from the intersection with Portage Road, which ran parallel to the Niagara River, a messenger arrived with orders from Riall to retire on Queenston. Scott retraced his route up the Beechwoods Road, which ran along the escarpment to Queenston. After covering four miles, another message arrived ordering Scott to move to the junction of Lundy’s Lane and Portage Road as quickly as possible. With the evening coming on and frustrated by these countermarches, Scott now heard artillery fire coming from the south, and had his men increase their pace to double time.28

Movements by the enemy had caused the need to countermarch. Earlier, around 2:00 p.m, when reports of the British advance had reached his headquarters at Chippawa, Jacob Brown, concerned that his supply base at Fort Schlosser was threatened, sent Brigadier-General Winfield Scott north to Queenston to report on the situation there. Three hours later, the four regiments of Hercules Scott’s 1st Brigade, accompanied by artillery and cavalry, crossed the bridge over the Chippawa River toward their objective. For his part, Riall, who had not yet recovered his nerve following his defeat at Chippawa, concluded that he was facing the entirety of Brown’s army, and ordered the forces commanded by Scott and Pearson to converge on Queenston, where he hoped to fight the enemy on more even terms.29

The positions of American, British, and Canadian troops during the final phase of the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, July 25, 1814. MB

When Lieutenant-General Drummond, who had been following Morrison’s force, learned of the American advance, he quickly rode ahead until he found Pearson, who was now about two miles north of Lundy’s Lane, and ordered him to return to his earlier position on a high feature on Lundy’s Lane that had a commanding view of the Portage Road. Pearson and Riall arrived at the hill at Lundy’s Lane around 7:00 p.m., where they found Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond and Captain Norton,30 who had gone forward together to observe the American advance. Having found the position atop the hill abandoned, Drummond and Norton had decided to remain there after noticing dust clouds from the north that signalled the approach of a British column. No sooner were Pearson’s twelve hundred men and five artillery pieces deployed along a thousand-yard-long line centred on a hill on the east-west ridge running along Lundy’s Lane than the American Winfield Scott arrived with his brigade, having made their approach from Chippawa using the Portage Road. Within minutes, the opening shots were fired, and the Battle of Lundy’s Lane was under way.31

Meanwhile, in the late afternoon, Morrison, his men having been rested and fed, continued toward Lundy’s Lane. It had been a long and difficult day for the flank companies of the 104th. Marching, countermarching, and now at the double, the men were hot, thirsty, and exhausted, having marched twenty miles. They approached Lundy’s Lane from the west and moved onto the battlefield around 8:30 p.m. By then, the battle had been raging for over an hour. Despite a determined attack by the Americans that nearly broke the militia on the British left flank, the line was intact, and a lull in the fighting gave Lieutenant-General Drummond time to realign his position and incorporate Hercules Scott’s men into the line.32

Directed onto the field by a member of Drummond’s staff, the 1st Foot and the flank companies of the 103rd and 104th were placed to extend the “front line on the right,” where Drummond “was apprehensive of the enemy outflanking” him.33 The 1st Foot was in extended line, flanked by the light and grenadier companies of the 103rd Foot, with the flank companies of the 104th under Leonard and Shore in a skirmish line on the extreme right. The smell of powder and the cries of wounded men filled the air, and the bodies of dead and wounded men and horses were strewn about.

As night approached, and amid sporadic firing, the men found it difficult to adjust their eyes to the fading light.34 Within minutes of taking up their position, the men of the 104th saw a “black line rising” to their front, and they “poured a rolling volley on them.”35 The response came from a voice shouting “We’re British!”36 and other cries that the troops who were approaching were not American. The 104th ceased fire immediately, but the 103rd grenadier company unleashed one more volley before the situation was understood. The victims of the friendly fire in the fading light proved to be the Glengarry Light Infantry, who, having been sent forward earlier to engage the Americans in the flank, were now moving back into the main line.37

Leonard was then instructed to move both companies of the 104th to the northern edge of the hill to form a reserve behind the rear of the 89th Foot, who occupied the centre of the British line. Although the men were sheltered by a split-rail fence, the officers, hoping to reduce casualties from the persistent enemy fire, instructed them to lie down. One soldier belonging to the light company, Private Nathaniel Nickerson, who was also servant to Captain Shore, ignored the shots whizzing around him and the repeated orders of the officers to stay down, and remained standing. The young private explained that the heroism of his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond, “sitting on that great horse, up there amongst all the balls,”38 inspired his reckless behaviour. How could anyone, Nickerson cried, “not admire the fellow’s generous heroism!”39 Drummond was indeed an inspiration to all who saw him. Le Couteur shared Nickerson’s sentiment at the sight of their commanding officer “seated on his war horse like a knightly man of valour as He was exposed to a ragged fire from hundreds of brave Yankees who were pressing our brave 89th [Foot].”40

By this point, the battle had been raging for over two hours. The British had started well, but Riall had been wounded and taken prisoner, and the American Brown, who had been reinforced by another brigade, chose not to outflank Drummond from the west, but instead struck at the British centre and left. The American attack succeeded in capturing the eight guns lining the crest of the hill and forcing the British off the ridge. Regrouping in the low ground to the north of Lundy’s Lane, Drummond readied his men to recapture his artillery.41

The 104th’s Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond described the next phase of the battle as “the most desperate attempts to regain the hill.”42 With the “confusion of the columns rencontering [sic] in the dark” and the “ridiculous mistakes which could only occur fighting an army speaking the same language,”43 it took the British general and his staff thirty minutes to sort out the mass of men and prepare for the counterattack. The British commander’s plan was to form his men into line, and then advance silently up the slope, retake the guns, and regain the hill. As the British line was assembling, staff officers, including Lieutenant Henry Moorsom of the 104th, rode up and down the ranks, passing on details for the attack and ensuring ammunition was being redistributed and the line properly arrayed.44

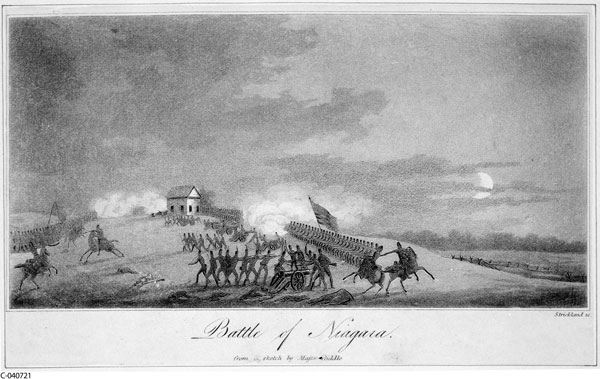

The Battle of Lundy’s Lane was the largest engagement in the northern theatre during the War of 1812. Both flank companies of the 104th Foot were present, as were Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond, who was on detached service, and Lieutenant Henry Moorsom, who died during the battle while serving on the staff. LAC C000407

With three thousand men, the Right Division was still an imposing force, and Lieutenant-General Drummond formed it into a single line divided in two wings and a reserve. The regular troops and incorporated militia of the eastern wing would attack from the Portage Road to the slope of the hill. Fifty yards to the west and extending for another two hundred yards was the western wing, arranged in a line consisting of half of the 103rd Foot, seven companies of the 1st, the flank companies of the 104th, and the grenadier company of the 103rd. The Glengarry Light Infantry, some of the sedentary militia, and a group of First Nations warriors remained in forward positions near the centre of the western wing. Five companies of the 8th Foot, other sedentary militia, and more warriors were placed in reserve to the west along Lundy’s Lane.45

At 10:00 p.m. came the order to advance, but, for reasons that remain unclear, Drummond held the western wing in place. Nevertheless, anticipating that the Americans might attack the British right, the 104th’s William Drummond had his men drag dead horses into a line forming a breastwork from which they could return fire under cover. To their left, the eastern wing began moving up the hill, halting and firing as they went. What followed was a confusing, intense action lasting nearly thirty minutes, and ending with the British and Canadians retiring down the hill. Fifteen minutes later, Lieutenant-General Drummond repeated the attack, which proved “more severe” and “longer continued than the last.”46 As musketry fire was poured into them, the Americans began to waver, but, as the British were unable to press the attack, the firing gradually died down, and Drummond’s eastern wing again disappeared into the low ground.47

Shortly before 11:30 p.m., despite the intensity of the fighting, the British launched a third attack. Drummond continued to enjoy superior numbers over Brown, who had no more than eighteen hundred troops remaining, and the British commander chose to attack his opponent head on. Once more, the British closed with the Americans, this time meeting with success and recapturing their artillery. Drummond’s men, now completely spent and unable to continue, retreated into the darkness, and he withdrew the Right Division westward along Lundy’s Lane for half a mile to the Lundy farmhouse, where they spent the night. The British commander hoped to renew the action the following day.48

Both armies had fought to a standstill in one of the largest and hardest fought actions of the War of 1812. Nearly 6,400 troops were committed to the battle, and each army suffered nearly 900 casualties.49 The arrival of the 104th’s grenadier and light companies following the opening stage of the battle, and their limited involvement in the effort to regain the hill, spared them heavy losses. The official return of casualties for the Right Division, compiled shortly after the battle, listed the 104th’s losses as one soldier killed and five missing. Subsequent research paints a slightly different picture. Private B. John Martinette was the sole casualty from Captain Leonard’s grenadier company, captured in the latter stages of the fighting. In Captain Shore’s light company, Privates Joseph Blanchard, Jean Baptiste Bourgignon, John B. Fayette, Moses Holmes, and Ednor Lock also became prisoners of war. Captain Robert Loring, an aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-General Drummond and described by one Canadian militia officer as “[c]ool and determined in the field,”50 was wounded and taken prisoner as he was delivering orders.51 The only member of the 104th to be killed in the battle was Lieutenant Henry Moorsom, who fell early in the action while “[c]heering on the Royals [1st Foot].” He had served on Lieutenant-General Drummond’s staff as deputy assistant adjutant general since August 1813, and as Lieutenant Le Couteur noted afterward, the loss of their “excellent friend” was very troubling to his brother officers, especially as Moorsom was “the last of four or five brothers killed in the Service.”52

At first light the next morning, the Right Division returned to the battlefield expecting the action to continue, only to find that the Americans were gone. Before them was a field littered with dead, dying, and wounded men, and so began the process of taking the wounded from both sides to farmhouses, where the regimental surgeons established field hospitals, and disposing of the dead. As the local hospitals were quickly overwhelmed with casualties, some of the wounded were evacuated to Fort George. The Right Division men also did what they could to comfort the dying. In one act of compassion, Le Couteur came across the mortally wounded Captain Abraham Hull, a company commander in the 9th US Infantry, and offered the American brandy and water, and promised to deliver several personal items to his family.53

For over a week after the battle, the two armies remained out of contact. Lieutenant-General Drummond kept his division at Queenston, where he contemplated his opponent’s next move while dealing with the threat that the appearance of Chauncey’s naval squadron on Lake Ontario posed to his line of communication and to the forts at the mouth of the Niagara River. Toward the end of the month, following reports from a reconnaissance party he had sent forward to regain contact with the Americans, Drummond decided it was time to advance closer to the enemy and reorganized the Right Division into an advance body of two brigades of infantry, a reserve, and an artillery park. To cover the advance of the division, William Drummond was given command of a “flank battalion” consisting of the light companies of the 89th and 100th Foot and the flank companies of the 41st and 104th.54

For the Americans, the pause allowed a period of consolidation. At the end of July, Major-General Brown’s Left Division mustered 2,125 men fit for service, but there was a serious shortage of officers. Brown himself had sustained a wound during the battle that forced him to transfer command to Brigadier-General Eleazar Ripley. Following the withdrawal to Chippawa, however, Ripley had proposed quitting Upper Canada altogether and returning to the United States. Brown overrode the suggestion and instead ordered Ripley to withdraw to Fort Erie. The Left Division arrived at the fort on July 28 and began improving the fortifications. By now, Brown had little confidence in Ripley and decided to replace him. On August 4, Brigadier-General Edmund Gaines arrived and took command of the Left Division.55

While the regiment’s flank companies campaigned in the Niagara Peninsula, the five line companies of the 104th had remained at their posts along the St. Lawrence River at Gananoque, Prescott, and Cornwall. The 181-mile-long corridor of the upper St. Lawrence, stretching from Montreal to Kingston, was integral to the defence of Upper Canada, acting simultaneously as a front, a flank, and the lifeline for the British forces in Upper Canada.56 As well, nearly half the province’s population of 77,000 lived along the river. During the first six months of the war, American forces had mounted predatory raids aimed at disrupting river communications and securing supplies. In early 1813, the British succeeded in chasing the last group of American regulars from Ogdensburg, on the American side, and except in November, when the American army under Major-General James Wilkinson moved downriver in its unsuccessful offensive toward Montreal, the British maintained control of the river until the end of the war.

Beginning in early 1813, the need to maintain uninterrupted communication between Montreal and Kingston led to the construction of fortifications at several points along the river. Work started on a blockhouse at Prescott, where open navigation for bateaux moving to Kingston began. This defensive work grew to become a fort, which, in July 1814, was named in honour of the Duke of Wellington. Also located at Prescott were a number of gunboats — vessels of forty to sixty feet in length, armed with one or two artillery pieces, and crewed by a mix of regular soldiers, Royal Navy seamen, and militia.57

Records do not indicate the disposition along the St. Lawrence of the individual line companies of the 104th, but we know that in the Kingston area were No. 3, commanded by Captain William Bradley, No. 5 under Captain Edward Holland, No. 6 under Captain Andrew George Armstrong, and No. 8 under Captain Charles Jobling. The identity of a fifth company and its commander cannot be confirmed, although it was either No. 7 or No. 10, both having moved to Lower Canada in the late spring of 1813, but only one of them being sent to Kingston. The movements of the individual companies are also difficult to trace. In June 1814, they were distributed between Fort Wellington and Cornwall, but by July they were concentrated at Kingston, with a detachment at Gananoque; later that month, the line companies returned to Fort Wellington, where they remained for the remainder of the year.58 With Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond’s detached service to the staff, Major Thomas Hunter was appointed acting commanding officer in January 1814, and continued in that role following Drummond’s departure for the Niagara Peninsula in July.59

In addition to their regular garrison duties, the companies of the 104th often provided detachments to crew the gunboats. During the summer of 1814, gunboats and larger naval vessels from both sides routinely skirmished on the river between Prescott and Kingston. In a typical incident on May 14, a subaltern and ten men from the 104th and an equal number of Voltigeurs Canadiens set off from Gananoque under the command of Lieutenant John Majoribanks of the Royal Navy in pursuit of an American sloop. Losing sight of their quarry, the party landed at Cape Vincent, New York, where they destroyed a blockhouse and barracks and took several prisoners before returning to Kingston. In June, American gunboats took the crew of Black Snake, commanded by a militia officer; in response, a British gunboat was dispatched to pursue the Americans. Its commander, Lieutenant Alexander Campbell of the 104th, and crew of eighteen men “fell in with [the enemy and] in a most gallant manner” and after only firing “a few shot”60 from their single carronade, obliged the enemy flotilla of one gunboat and four other vessels “to abandon and scuttle their prize.” Unfortunately, the enemy escaped with his prisoners, but the gun and stores from the scuttled British gunboat were recovered.61

Other duties were less arduous and included providing escorts for American prisoners of war. In January 1814, for example, Lieutenant Frederick Shaffalisky took charge of a party of two corporals and twenty privates from the Glengarry Light Infantry to escort prisoners of war, en route to Montreal, on the leg from Kingston to Prescott.62 Farther to the east, the small detachment of the 104th at Cornwall, which earlier in the year had served as a base for raiding enemy depots across the river, found that, with the threat from the Americans largely eliminated, their task was mostly limited to protecting the supply bateaux moving along the river.63

The relative quiet in this theatre also provided an opportunity to see to the interior economy of the regiment. Sickness and injury took a greater toll on the troops than did combat, and often left men unfit for regular service but still capable of employment. The end of each campaign season left the regiment with a pool of men declared unfit for active service, and the Royal Veteran battalions provided a means of using these men to garrison fortified points, such as Fort Wellington, and freeing up regular units for field operations. Accordingly, in 1812, one man was transferred to the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion, in 1813 another eight followed, and in 1814 another thirty-two men left, the majority of them departing in November following their return from the Niagara Peninsula.64

Meanwhile, in the Niagara Peninsula, the Right Division had moved to within six miles of Fort Erie. Reports from First Nations scouts indicated that the Americans had retired to Fort Erie, where they had begun to expand the works to house the entire Left Division. Lieutenant-General Drummond concluded that, lacking the manpower, supplies, and ordnance to conduct a prolonged siege of Fort Erie, he would threaten the American line of communications at Black Rock and Buffalo and, by the “destruction of the Enemy’s Depot of Provisions,”65 force the Americans from the fort. To achieve this goal Lieutenant-Colonel John Tucker was given command of a light brigade of six hundred men divided into three groups. The main body consisted of four line companies and the two flank companies from the 41st Foot under Lieutenant-Colonel William Evans; the second group was formed from the grenadier and light companies of the 104th and the light companies of the 89th and 100th Foot, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond; and the third group was a detachment of artillery. Once Tucker had succeeded in taking his objective, a party of sailors was to capture enemy naval vessels moored nearby.66

At 11:00 p.m. on August 2, Tucker’s light brigade began crossing the Niagara River; by midnight, they were all across. Although he was only two miles from Black Rock, Tucker halted for four hours to await daylight before continuing toward his objective. Then, instead of employing one of the light companies as an advance guard, a task for which the Light Bobs were most suited, Tucker sent Evans and the 41st Foot forward. In his journal, Lieutenant Le Couteur criticized Tucker, whom he called “Brigadier Shindy,” meaning he considered Tucker to be unsteady in action. William Drummond also had little regard for Tucker’s professional acumen, but chose to withhold his criticism as it was “no business of his.”67

Around 4:30 a.m., as Evans’s force approached the bridge over Conjocta Creek, just north of their first objective at Black Rock, they came under heavy fire from the enemy. Although numbering no more than 240 men, they had learned of the British advance and were entrenched on the opposite bank. With the element of surprise lost, the six companies of the 41st fired a volley, broke, then fled to the rear. The flank companies from the 89th, 100th, and 104th remained steady, however, and the grenadier and light companies of the 104th returned fire as Drummond rushed forward to where Captain Shore had deployed the light company and ordered Le Couteur to take Sergeant Peter (Pierre) Roy and a detachment of Light Bobs and see what lay ahead.68

Meanwhile, order was restored among the 41st, and once reformed, Tucker sent its companies back to the bridge. There was a ford about a mile upstream, but rather than attempt a flanking move, Tucker opted to continue the firefight around the bridge. The action continued for nearly three hours as the Americans — rifle armed, which allowed them more accurate fire at a greater range, albeit with a slower rate of fire than the musket-equipped British — held off the attackers. Then, in the afternoon, thinking the Americans were about to stage a large counterattack, Tucker broke off the engagement and ordered his men back across to the Canadian side of the Niagara River.

The action had achieved nothing, and cost thirty-three casualties: twelve killed, seventeen wounded, and four missing. In his report, Tucker stated that, from the 104th, one sergeant and five men had been killed in the action, one man had been wounded, and another four were missing, although the records reveal only a single death in the regiment, that of Sergeant Pierre Roy, killed when the reconnaissance party under Le Couteur came under enemy fire. Four privates, all of them from the light company, were also missing.69

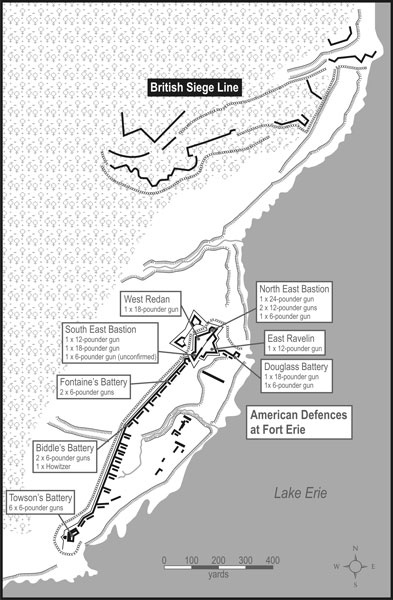

Disappointed with the results and furious with Tucker, Lieutenant-General Drummond now had to contemplate establishing a siege of Fort Erie. On August 3, as the lead elements of the Right Division pushed back the American pickets, Drummond was finally able to see his objective and to study the improvements the Americans had made to the fort. In short order, they had reinforced and expanded the original fortification, a stone fort consisting of two demi-bastions — two-sided angular works made of brick and sod that projected outwards — connected by an earthen curtain wall on their west side, and two stone buildings on the east. A low wall connected the northeast demi-bastion to the shore of Lake Erie, while the curtain wall was extended nearly nine hundred yards to the south to a sand mound known as Snake Hill, which was also fortified. Inside were twenty-eight hundred men and eighteen pieces of ordnance, distributed between the northeast bastion and along the entire line to Snake Hill. A dry ditch surrounded the outer walls of the stone fort, and abattis had been placed along the perimeter. Batteries across the river at Black Rock provided additional fire support, and three naval schooners on Lake Erie guaranteed uninterrupted communication with Buffalo. The enemy position was formidable, and when Le Couteur saw it he remarked that it was “an ugly Customer for” the Right Division’s “fifteen hundred men to attack.”70

Drummond would have to satisfy a number of conditions before he could assault the fort. First was the denial of supplies and reinforcements to the enemy, which would be achieved by cutting their line of communication to Buffalo. Second, in accordance with siege doctrine, batteries would have to be established to wear down the enemy’s morale and to batter the walls to create one or more breaches through which the attackers would assault. Finally, a large number of men would be necessary to take the fort by attacking it at several points.

Lacking the resources, ordnance, and manpower to isolate Fort Erie, the best Drummond could achieve was to erect a single five-gun battery. An officer of the Royal Engineers supervised the construction of the gun platforms and works, while the infantry provided the labour. Members of the flank companies of the 104th contributed work parties and also manned the pickets that were thrown forward to provide warning and protection from any enemy threat against the British siege line. Skirmishes between the British and American picket lines became part of the daily routine as the Americans attempted to hamper the working parties at the battery. First Nations Warriors, militia, and regulars, often commanded by the 104th’s William Drummond, routinely ventured out to clear American patrols from the neighbouring woods.71 As the days passed, the casualty toll rose, and in the first two weeks of August, the 104th lost five men killed, three missing, three taken prisoner of war, and one desertion.72

On August 12, the enemy sent out eighty riflemen to determine whether the British were erecting a second battery. In the course of their reconnaissance, the Americans attacked several pickets manned by the 104th. Lieutenant Le Couteur described this sharp action in his journal: “The enemy made a desperate attempt to turn our flank but after an hour’s hard fighting they were driven back with serious loss, leaving many of their dead and rifles along our front.”73 Three privates from Captain Leonard’s Grenadier Company74 died in the attack and one man was missing. Some good news came later that day from Lake Erie, where a detachment of sailors commanded by Commander Alexander Dobbs captured two American schooners from their anchorages off Fort Erie following a fierce hand-to-hand struggle with the American crews.75

After all the hard work, however, the sole British battery was found on completion to be nearly eleven hundred yards from the stone fort — too far away to be effective. Regardless, believing that the two-day bombardment that had begun on August 13 had produced “a sufficient impression” on the “works of the enemy’s fort,”76 on August 14 Lieutenant-General Drummond issued orders for the assault, which was to take place on the following morning.

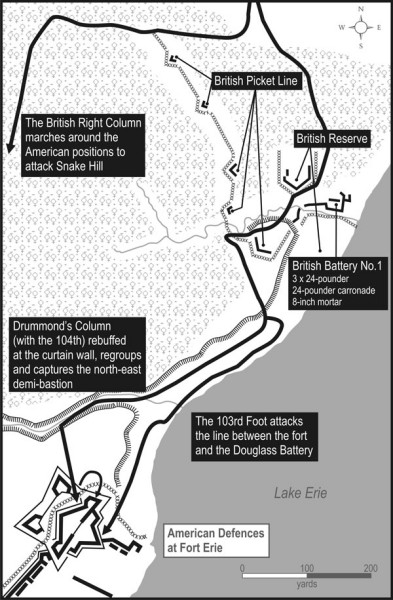

Drummond’s plan was ambitious. While a group of warriors and soldiers made a diversionary demonstration from their pickets at the American centre, three columns were to make the assault at different points. Beginning at 2:00 a.m., a fifteen-hundred-man column commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Victor Fischer was to seize the southern end of the defences between Snake Hill and the lake. This was to be main attack. Once Fischer had penetrated the American line, the left column, seven hundred men from the 103rd Foot under Lieutenant-Colonel Hercules Scott would seize the enemy’s northern entrenchments between the fort and the lakeshore. To Scott’s right, a second column commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond would attack the fort itself. A reserve force under Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon of the 1st Foot would be ready to exploit any success.77

Drummond’s column numbered 340 men and included the flank companies of the 41st (one hundred and ten men) and 104th (seventy-seven men), one officer and a dozen men from the Royal Artillery, and a contingent of ninety seamen and fifty Royal Marines under Commander Alexander Dobbs of the Royal Navy. In accordance with the established doctrine for an assault against a fort, Captain William Barney of the 89th Regiment was nominated to guide the lead elements of Drummond’s column to their assault position, from where he would then point out the route to their objective.78

Both Drummond and Scott had uneasy feelings about the attack, each having premonitions of death. Scott wrote to his brother that “I have little hope of success for the manoeuvre;”79 in Drummond’s case, “something whispered” to him as he observed the artillery fired on August 14 “that this would be his last day.”80 On the morning of the attack, Drummond breakfasted with several officers, including his friend William Dunlop, the surgeon of the 89th Foot, who later recalled:

We sat apparently by common consent long after breakfast was over. Drummond told some capital stories, which kept us in such a roar that we seemed more like an after dinner than an after breakfast party. At last the bugles sounded the turn-out, and we rose to depart for our stations; Drummond called us back, and his face assuming an unwonted solemnity, he said, “Now boys! we never will all meet together here again; at least I will never again meet you. I feel it and am certain of it; let us all shake hands, and then every man to his duty, and I know you all too well to suppose for a moment that any of you will flinch it.” We shook hands accordingly, all round, and with a feeling very different from what we had experienced for the last two hours, fell into our places81

The disaster was far greater than either Drummond or Scott reckoned. Lieutenant-General Drummond had ordered the men of the Regiment de Watteville, advancing on the far right, to remove their flints to avoid any chance of losing the element of surprise by the accidental discharge of a musket. They were then held up by trees felled to block their route, causing several of the companies to move toward Snake Hill. An attempt to get into the battery position failed when the scaling ladders thrown up against the parapet were found to be too short. The enemy poured artillery and musket fire into the men crowded below the battery, causing many to break and run. A combined effort by the light companies from the Regiment de Watteville and the 8th Foot — the latter allowed to retain their flints — to outflank the American position also failed. The remainder of the 8th Foot, coming behind them, fared no better and, unable to continue with the attack, Fischer’s column fell back.82

To the north, the feint by warriors and troops from the picket positions against the enemy’s centre also went wrong. Scheduled to begin before Fischer’s assault, the First Nations contingent moved to the north, where it joined Drummond’s assault on the fort, while one picket made a long-delayed demonstration against the enemy’s centre. Despite the failure of this portion of the overall assault, the Americans perceived the threat was great enough to prevent the units manning that portion of their line from moving elsewhere.83

At around 2:45 a.m., sentries inside the fort heard sounds in the distance. It was Drummond and Scott, moving their columns from the British camp along the lakeshore toward their objectives. As they neared the fort, Scott moved closer to the lakeshore, while Drummond aimed his directly at the fort. Scott had his men moving in a mass about forty ranks deep and fifteen wide. Their route, however, brought them directly in front of two American artillery pieces and 180 armed men. The Americans opened up with a devastating fire that halted the column about 150 yards away, forcing it to retire into the darkness. After regrouping, Scott launched two more attacks that also were repulsed by heavy fire.84

Meanwhile, during the final approach to the fort, Drummond was able to shield his column from the effect of the guns in the northeast demi-bastion by using dead ground, largely provided by mounds of earth strewn about the field. Captain William Barney was in the lead, guiding the “forlorn hope” — the detachment, made up mainly of sailors carrying scaling ladders, that would make the first assault on the fort — to its attack position. Colour Sergeant Richard Smith of the 104th, who had joined The New Brunswick Fencibles in 1805, was in command of the forlorn hope; if he survived the action, his reward would be a commission as an ensign.85

Le Couteur described the next stage of the attack by Drummond’s column. Once the forlorn hope “got to the ditch” that surrounded the curtain wall on the northwest face of the fort, they “jumped in, reared the Scaling ladders and,” turning towards the remainder of the column, “cheered us as they mounted”86 the ladders. Inside, the soldiers of the 19th US Infantry withheld their fire until Drummond’s men appeared above the parapet. As the forlorn hope and other members of the column, including soldiers from the 104th, worked their way up the ladders and pushed their way in, a terrific melee took place on the small gun platform inside the wall. The Americans momentarily pushed the British back, but, after regrouping, the redcoats made a second and then a third charge. Unable to break through the defenders, however, the column withdrew and readied still another attempt.87

Following the rebuff at the curtain wall, William Drummond’s column succeeded in storming the northeast demi-bastion by escalade using ladders thrown up against the wall. Photograph by author

The survivors of the two columns felt their way along the edge of the fort until they met near the northeast demi-bastion. Drummond took control of both groups and, seeing that they appeared to be in a blind spot in the defences, ordered another assault aimed at the northeast demi-bastion.88 Once again ladders were thrown up against the wall, and Drummond himself was the first up. The thirty American artillerists manning four guns inside were so completely taken by surprise that the bastion fell within minutes. Drummond, now joined by members of his 104th Foot, regrouped his men and led them toward the seven-foot-wide passageway that provided access from the demi-bastion into the fort itself. Major William Trimble, the American commander in the stone fort, had noticed the British officer leading the assaults who had “advanced as far as the Door of the mess house,” a stone building adjacent to the entranceway to the demi-bastion, and when Drummond rushed forward again, Trimble gave his men the “order to kill him.”89 Seconds later, Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond fell from the concentrated fire of the defenders.90 The men from Drummond’s regiment among the two or three hundred packed into the bastion might have been inspired by the death of their commanding officer to press home the attack; instead, however, the momentary pause following Drummond’s death took the impetus out of the assault.91

The interior of the northeast demi-bastion as the American defenders would have seen it. Heavy fire covered the narrow defile into the fort, and it was during one of the charges that Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond fell, somewhere near the door of the cookhouse on the right.

Photograph by author

It was now about 4:00 a.m., and reinforcements from both sides rushed to the passageway as Captain Joseph Glew, commander of the light company from the 41st, took charge. The action turned into a stalemate as neither side could gain an advantage over the other in the narrow defile. Then, a detachment from the Royal Artillery who had made their way into the demi-bastion swung one of the guns round and opened fire on the Americans. Suddenly, there was a massive tremor as the demi-bastion exploded, blowing men, guns, and equipment into the air and landing as far as three hundred yards away. Le Couteur was climbing a ladder into the bastion when it blew up. Knocked unconscious, he later recorded what he saw once he recovered from the shock a few minutes later,

lying in the ditch fifteen or twenty feet down where I had been thrown by a tremendous explosion of gunpowder which cleared the Fort of three hundred men in an Instant. The platform had been blown over and a great beam had jammed me to the earth but it was resting on the Scarp. I got from under it with ease, bruised but otherwise unhurt. But what a horrid sight presented itself. Some three hundred men lay roasted, mangled, burned, wounded, black, hideous to view. On getting upon my legs, I trod on poor L[ieutenan]t. Horrens [Le Couteur likely meant Captain S.B. Torrens of the 1st Foot] broke leg of the 103rd, which made me shudder to my marrow. In placing my hand on Captain [George] Shore’s back to steady myself from treading on some other poor mangled person, for the ditch was so crowded with bodies it was almost unavoidable, I found in my hand a mass of blood and brains — it was sickening.92

As the survivors from both sides regained their senses, the Americans recommenced firing on the attackers, who were left with no option but to withdraw. From the battery position in the rear, the British guns tried to provide covering fire as the survivors made their way back. Regaining the British lines, Le Couteur was called over by Lieutenant-General Drummond, who asked him: “Do you know anything about Y[ou]r Colonel?” For his part, shaken by what he had experienced, Le Couteur “could not articulate for grief. ‘Killed, Sir.’ ‘Col. Scott?’ ‘Shot thro’ the head, Sir, Your Grenadiers are bringing Him in, Major Leonard & Maclauchlan wounded & Capt. Shore a prisoner.’ The General felt for me and said ‘Never mind, Cheer up. You are wanted here. Fall in any men of any regiment as they come up, to line our batteries for fear of an attack.’ Duty instantly set me to rights and I was actively employed cheering & ranging the men as they came in. Our men behaved.”93

The approaching daylight revealed the carnage on the field. Bodies dotted the landscape, and as officers and men struggled to reach the British lines, the Americans continued firing on them. From an assault force of 3,073 men, Lieutenant-General Drummond reported 57 dead, 309 wounded, and 539 missing, for a total of 905 casualties. For the survivors of the explosion that destroyed the northeast demi-bastion, no cause for the detonation of the powder magazine located under its platform could be determined, and since then no evidence has been found offering a convincing explanation of this mystery.94 The grenadier and light companies of the 104th Foot had suffered grievously in the attack. Sergeant John McEachern and sixteen privates were dead; Captain Richard Leonard, commander of the grenadier company, Lieutenant James McLaughlin, and twenty-seven other ranks were wounded. One man was missing and five were prisoners of war. Discrepancies in the returns make it difficult to be precise, but of the seventy-seven men from the flank companies who were fit for duty on the morning of the assault, between forty-seven and fifty-four of them had become casualties. Colour Sergeant Smith, commander of the forlorn hope, had survived unscathed, but as the assault had failed, he did not receive a commission.95

Surgeon William Dunlop described Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond, the much respected and beloved commanding officer of the 104th, as having “everything that could be required in a soldier; brave, generous, open-hearted and good natured,” and “a first-rate tactician.”96 The enemy found his body in front of the mess building inside the fort at a point farther than any other attacker had penetrated the defences. The Americans stripped his corpse to the shirt and displayed it for the rest of the day. The double-barrelled gun Drummond customarily carried and the beads a group of warriors had presented him were found on the field by Le Couteur.

Despite the failure of the assault and the heavy losses to the Right Division, Lieutenant-General Drummond decided to continue with the siege, and ordered the construction of a second battery about seven hundred yards from the fort. Commodore Chauncey’s intermittent blockade of the mouth of the Niagara River plagued the reinforcement of Drummond’s army and further construction, however, as the flow of supplies was reduced to a trickle. Nonetheless, work on the battery continued, and by the end of August it began firing on the Americans.97

Monument dedicated in 1904 to the officers and men who fell during the siege of Fort Erie. Originally placed in the ruins of the fort, the monument was moved to its current location in the late 1930s during the restoration of the fort. Beneath the monument are the remains of 150 British and three American soldiers discovered during the restoration.

Photograph by author

The survivors of the 104th manned the pickets, where they routinely came under enemy fire, and under the supervision of engineering officers, they also formed work parties to construct the battery. Royal Engineer Lieutenant George Philpotts, who was supervising this activity, complained that the infantry provided only small work parties for this task, reflecting the dire state of manning in the Right Division, where the grenadier and light companies of the 104th were now down to “Eight officers to Eighteen men.”98 The only reinforcements to arrive were officers, as Captain George Jobling, Lieutenant René-Léonard Besserer, Lieutenant Waldron Kelly, and Lieutenant Thomas Leonard joined the “debris” from the two companies in early September. As Captain George Shore was placed in charge of invalids at Fort George, command of this group fell to Jobling.99

As work parties toiled on a third battery, Drummond considered making another assault in early September, but then changed his mind. Then, on September 17, the Americans attacked the British batteries, resulting in another five hundred casualties to each side. The 104th was not in the line that day and suffered no casualties.

Tragically, Drummond had already concluded nothing further could be achieved, and with the season growing late, the absence of Yeo on the lake, dwindling ammunition supplies, persistent food shortages, near constant rain, and sagging morale that created the “smells of retreat,”100 he had ordered the guns to be withdrawn from the batteries on September 16, and on September 21 he withdrew the Right Division to Chippawa, and then redistributed his units. The forwardmost group was positioned between Frenchman’s Creek and Chippawa, a battalion was placed at Chippawa, and another at Lundy’s Lane. The flankers of the 104th were moved to Queenston, where, along with the 89th Foot, they assisted with the movement of supplies on the Niagara River. These dispositions allowed Drummond to remain in contact with the enemy, while masking a potential flanking movement he was considering along the American side of the river. The siege was over, but the campaign was not.101

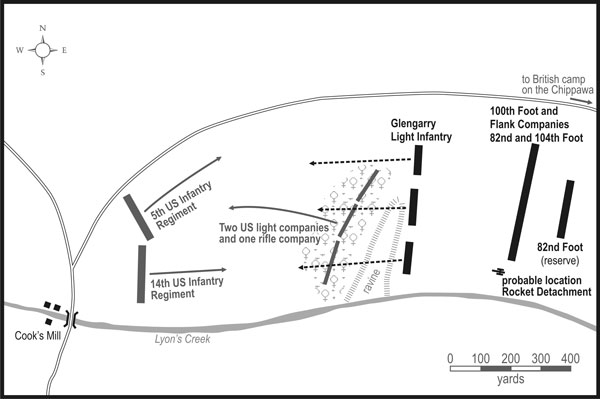

In October, a large American reinforcement arrived at Fort Erie from its base at Plattsburgh, New York. Major-General George Izard, now commanding the American Left Division, also took command of the fort and began offensive operations against the British. His plan was to draw the British from their entrenchments north of the Chippawa River and into open battle. For his part, when Drummond learned of Izard’s arrival, he thinned out his troops between Frenchman’s Creek and the Chippawa River, ordered the works at Chippawa to be improved, and sent the 100th Foot, a troop of the 19th Light Dragoons, and two guns to join the 104th and 89th at Queenston, forming the whole into a mobile reserve under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel The Marquess of Tweeddale. Unable to draw Drummond from his defences, Izard then sent a one-thousand-man detachment under Brigadier-General Daniel Bissell to Cook’s Mills, on Lyon’s Creek, to threaten the British right flank and seize supplies believed to be stored there.102

On October 18, Drummond sent Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Myers with the Glengarry Light Infantry and a seven-company detachment of the 82nd Foot to determine what the Americans were doing. Drummond also sent a second force farther inland to destroy a bridge over the Chippawa River, fearing the Americans might use it to outflank him. After receiving reports of upwards of two thousand Americans advancing against Cook’s Mills, Drummond sent Tweeddale, with the 100th Foot, the flank companies of the 82nd and 104th Foot, a 6-pounder gun, and a rocket detachment to reinforce Myers. Additional units were held at readiness should they be required. Tweeddale, whom Le Couteur described as “something like our dear [William] Drummond,”103 met up with Myers about three miles to the east of Cook’s Mills, where they established camp for the night. Myers sent the Glengarries forward to observe the American position, and during the night they skirmished with American pickets.104

On the morning of October 19, Myers deployed his seven-hundred-and-fifty-man force on the north side of Lyon’s Creek, about a thousand yards east of Cook’s Mill. His position was bounded by the creek on the left and a ravine to his front that ran perpendicular to the creek, beyond which stood a small wood and the Americans. East of the ravine was Tweeddale with the 100th Foot, the 6-pounder gun, and the rocket detachment. The Glengarries were ahead in skirmish order, followed by the 100th Foot and the flank companies of the 82nd and the 104th. The remainder of the 82nd was in reserve. Myers’s aim was to establish the Americans’ strength and intentions without becoming decisively engaged with the enemy. Before moving into their positions, the Glengarries treated the men of the 104th to “a hearty breakfast that saved” them “from famishing.”105 For now, Bissell kept the main body of his force near a bridge on the other side of the creek, while a rifle company and two light companies occupied the wood on the north side of the creek.

Myers opened the action by ordering the Glengarries to advance in two groups. The first headed directly for the ravine, while the other swung north to outflank the Americans. The American commander responded by sending two regiments across the bridge; one to deal with the Glengarries advancing directly across the ravine, and the second to sweep around the British right. Now outnumbered, Myers ordered his skirmishers back through the woods and the ravine, where they joined Tweeddale’s men. The Americans pursued, halted before the British line, presented their arms, and fired. A hot firefight ensued, which was joined on the British left by the lone artillery piece and four rockets under Lieutenant Thomas Carter. The few remaining Light Bobs of the 104th were in extended line covering the artillery. As pressure from the enemy mounted, the Light Bobs charged ahead to the ravine until forced to withdraw. The light company from the 82nd then came up in support, but as Tweeddale’s brigade was unable to force the Americans back, Myers withdrew from the field, leaving pickets behind to observe the enemy, who now turned their attention to destroying bushels of grain before returning to their camp. Myers then marched his men six miles to the east before they halted for the night, wet, weary, and hungry.106 The Americans reported seventy-seven casualties, Myers, thirty-six. Three men from Captain Shore’s company, Corporal Charles Lahore and Privates Isaac Church and William Lindsay, were killed in the action.107

Cairn erected in 1977 to commemorate the action at Cook’s Mills. The plaque describes the action and lists the units involved, including the flank companies of the 104th Foot. Photograph by Donald E. Graves

The skirmish at Cook’s Mills proved to be the last battle in this long and gruelling campaign, and the final action of the 104th Foot. With the enemy still present on Canadian territory, Drummond reorganized his effective units into two brigades, the first based at Chippawa and the second farther to the south at Street’s Creek, near the site of the Battle of Chippawa. After two major engagements, a minor battle, a siege, a great many skirmishes, and the effects of disease, the Right Division was a spent force. To ease the logistical situation in the division, all battalions or detachments that were seriously below strength or surplus to the new divisional structure were to be withdrawn. Among the worn units that were designated to depart were the flank companies of the 104th, the strength of which, between July 25 and October 18, had been reduced to a fraction of its original strength.108

On October 21, the surviving members of the 104th’s grenadier and light companies were ordered to Fort George, where they camped in an open field without “blankets, the fire out and frost on the ground.”109 Drummond, meanwhile, urged Yeo “to apply his ships to the only service which they could render to”110 his army by returning these companies and the 1st Battalion of the 8th Foot to Kingston. The following day, the two flank companies and the 8th Foot boarded the ship Niagara; they sailed on the twenty-third. The next day, the crowded conditions onboard became more comfortable when the men of the 8th were transferred to the Princess Charlotte. At noon on the twenty-fifth, Kingston came into sight, but the men’s hopes of going ashore quickly were dashed when they were told they could not land that evening. Finally, at 6:00 a.m., the following morning, the exhausted survivors of the flank companies marched off the ship and into quarters at Kingston.111

The Americans in the Niagara Peninsula, meanwhile, concluded that nothing could be gained by continuing the occupation of Fort Erie, and on November 5, as their last elements withdrew across the Niagara River to Buffalo, charges were detonated, destroying what remained of the fort. The 1814 campaign in the Niagara was over.

Military operations during 1814 were far from restricted to the Niagara Peninsula. That year, British forces lay siege to Plattsburgh, New York, occupied Washington, attacked Baltimore, and occupied Maine. The Americans raided the Western District of Upper Canada, failed in an attempt to recapture Fort Mackinac, and were defeated at Prairie du Chien, in what is now Wisconsin. In August, peace talks to end the war opened at Ghent. As the British and American commissions argued the finer points of diplomacy, it became clear that the war was becoming a stalemate, and both governments instructed their commissions to come promptly to an agreement. The signing of the peace treaty on Christmas Eve 1814 did not end the war, however, as the British commissioners insisted the treaty be ratified by both governments before it came into effect. Their rationale was that, on three previous occasions, the US government had reneged on treaties. Until this was concluded, the war dragged on.

As these events unfolded, the 104th Foot was concentrated at Kingston, with Major Thomas Hunter now in command following the death of Lieutenant-Colonel Drummond. In early November, the regiment reported its strength at one major, seven captains, eighteen lieutenants, thirty-eight sergeants, nineteen drummers, and three hundred and seventy other ranks fit for duty. Another thirty-two men were in hospital. At the end of the month, thirty-six men who were deemed unfit for continued service in the line were transferred to the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion, and another twenty were discharged and sent to England.112

Meanwhile, the remaining two companies of the 104th that had remained in the Maritimes were ordered to Lower Canada. Captain William Procter’s company from Prince Edward Island moved in two detachments, the first departing the island in August, and by October, the company was complete in Quebec. The following month, the company from Sydney joined them in Quebec.113

As well, two groups of boys belonging to the regiment were in Kingston and Three Rivers. Ten boys between ten and fifteen years of age and taken on strength between 1807 and 1811 were at Kingston; one, David Macintosh, was serving as a paymaster clerk. The second group of forty-four boys between ten and sixteen years old were at Three Rivers, and had also joined the 104th between 1807 and 1813. Of the total, twenty-four boys had fathers, uncles, or brothers serving in the 104th; the fathers of seven of these boys had been killed in action or died of wounds, and three boys had also lost brothers during the war. Sergeant Hugh McLauchlan, the father of twelve-year-old Alexander McLauchlan, had been killed at Sackets Harbor, and Hugh’s brother John had passed away in September 1813. Ten-year-old Dennis Smith lost his brother William, who died of wounds in June 1813, while his father passed away in September.114

Although the routine of training and garrison duty was broken by the occasional alarm, the situation in the Kingston area was relatively peaceful as the year ended. The town now had formidable defences. During the course of the war, the Kingston garrison had grown from 100 men in 1812 to 3,500 in the autumn of 1814. An elaborate system of defensive works protected the town, the naval base at Point Frederick, and the encampment at Point Henry. Le Couteur was confident the town was safe from a “coupe de main” even if the fleet were absent.115

Rain, snow, dysentery, and other diseases made conditions uncomfortable for the men of the 104th, although, at Cataraqui, Captain William Bradley oversaw the construction of new barracks.116 In February 1815, word of a possible peace treaty boosted spirits, but these were soured by the news of the British defeat at New Orleans. In the meantime, the Prince Regent had ratified the Treaty of Ghent at the end of December, followed, on February 17, 1815, by its ratification by President Madison. The war was over. News of the peace was welcomed at Kingston within a few days of its proclamation by a series of public and private celebrations. Jubilation spread among the ranks of the 104th, and for all there were many questions, including about the regiment’s future and the disposition of the men, boys, and their families.117