The Museum Visitor Experience Model

We have inherited from our forefathers the keen longing for unified, all embracing knowledge … But the spread, both in width and depth, of the multifarious branches of knowledge during the last hundred odd years has confronted us with a queer dilemma. We feel clearly that we are only now beginning to acquire reliable material for welding together the sum total of all that is known into a whole; but, on the other hand, it has become next to impossible for a single mind fully to command more than a small specialized portion of it. I see no other escape from this dilemma (lest our true aim be lost forever) than that some of us should venture to embark on a synthesis of facts and theories, albeit with second hand and incomplete knowledge of some of them—and at the risk of making fools of ourselves.

—E. Schrodinger, 1944

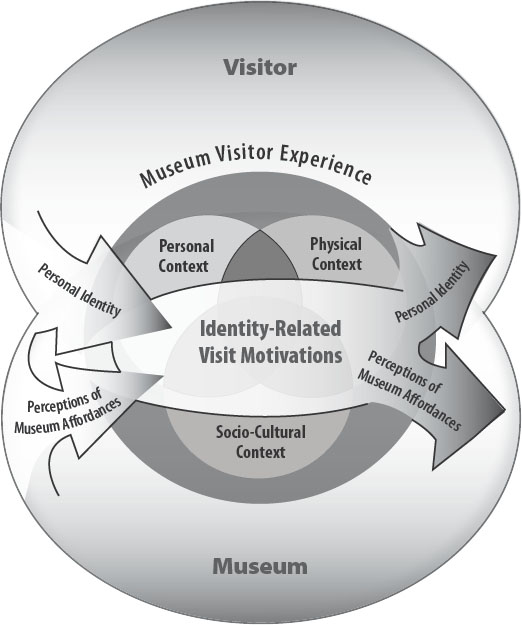

In the previous chapters, I have laid the foundations of a model that describes the museum visitor experience. It is a model that begins with the first conceptualization of the idea that visiting a museum in one’s leisure time could help to satisfy an identity-related need and concludes long after the museum visit ends through the individual’s development and enrichment of personal identity. In between, the individual’s identity-related visit motivation propels the experience, shaping not only the reason for visiting but also the actual visit and even, the laying down of long-term memories. It is a model that is based upon strong theoretical foundations and which is supported by considerable research collected both inside and outside of museums. In the final chapter of this theory section, I will summarize again the basic outline of the model as presented so far. I will illustrate how the model works using a detailed example, once again, using data from my research at the California Science Center. Finally, before moving into the practitioner section of the book, I will provide a big-picture overview of what this model can and cannot tell us about museums and their visitors.

OUTLINE OF THE MUSEUM VISITOR EXPERIENCE MODEL

• We cannot understand the museum visitor experience by looking exclusively at the museum (e.g., content of the museum or its exhibits and programs), or at the visitor (e.g., demographic characteristics of the visitor like age, income, or race/ethnicity), or even at easily observable and measurable attributes of museum visits (e.g., frequency of visits or the social arrangements of visitors as they arrive at the museum). The museum visitor experience is not something tangible and immutable; it is an ephemeral and constructed relationship that uniquely occurs each time a visitor interacts with a museum.

• Understanding the museum visitor experience requires appreciating that it actually begins before anyone ever sets foot in a museum. It begins with the confluence of two streams of thought on the part of the prospective visitor.

— An individual who wishes to satisfy one or more identity-related needs and decides to satisfy one or more of these needs through some kind of leisure time activity.

— The individual possesses a set of generic as well as specific mental models of various leisure settings, including museums, that individually and collectively support various leisure-related activities.

• These two streams of thought come together when an individual makes a decision that visiting a specific museum will be a good thing to do in his or her leisure time. That decision is generally justified by the prospective visitor believing that a good match exists between his or her perceptions of what a particular museum affords in terms of leisure-related opportunities and the specific leisure-related needs and desires that he or she possesses at that particular time and place. This decision-making process results in the formation of an identity-related visit motivation.

• Most identity-related museum motivations fall into one of five categories:

— Explorer

— Facilitator

— Experience seeker

— Professional/Hobbyist

— Recharger

NOTE: Although this entire process actually happens and is thus “observable,” typically the most “visible” piece of the process is the individual’s identity-related visit motivations. These represent the tangible and mostly conscious manifestations of the process and take the form of the self-aspects people use to describe their reasons/goals for visiting the museum to themselves. Other parts of the process are typically more deeply submerged in the person’s mind/unconscious and thus, are much more challenging to “see.”

• The actual museum visit experience is strongly shaped by the needs of the visitor’s identity-related visit motivations. The individual’s entering motivations creates a basic trajectory for the visit, though the specifics of what the visitor actually sees and does are strongly influenced by the factors described by the Contextual Model of Learning:

— Personal Context: The visitor’s prior knowledge, experience, and interest.

— Physical Context: The specifics of the exhibitions, programs, objects, and labels they encounter.

— Socio-cultural Context: The within- and between-group interactions that occur while in the museum and the visitor’s cultural experiences and values.

• The visitor perceives his or her museum experience to be satisfying if this marriage of perceived identity-related needs and museum affordances proves to be well-matched—in other words, visitors achieve what they expected. If expectations are not met, the visitor perceives that his or her museum visitor experience was less-than-satisfying. Currently, the overwhelming majority of museum visitors find their museum visit experiences very satisfying. This is in part because the public has a fairly accurate “take” on museums and thus possesses relatively accurate expectations. It is also in part due to human nature; we have a propensity to want our expectations to be met and work hard, often unconsciously, to fulfill them, even if it means modifying our observations of reality to match our expectations. Occasionally, however, bad experiences can and do happen.

• During and immediately after the visit the visitor begins to construct meaning from the experience. The specifics of the meaning a visitor makes of the museum experience is largely shaped by his or her identity-related motivation and the realities of the museum (under the influence of the factors highlighted in the Contextual Model of Learning). The following factors make certain experiences and memories more salient and thus, memorable than others:

— The choice and control visitors exercise over the experience.

— The emotional nature of the experience.

— The context and appropriateness of what visitors encounter in the museum.

• The resulting meanings that the visitor constructs of the museum visitor experience fall into two general categories. Since people visit museums primarily to satisfy one or more identity-related needs, it is not surprising that the major outcomes most visitors derive from their museum visit experience relate to identity-building. The sense of self that the individual projects on the visit, typically expressed as self-aspects, is strengthened, modified, and/or extended by the museum visit experience. Given the very diversity of identity-related needs that motivate people to visit museums, the range of identity-related outcomes is also diverse—ranging from increased understandings of art, history, science, and the environment to enhanced feelings of mental well-being. A secondary outcome is that the individual also enhances his or her understanding of museums. By virtue of direct experience in the museum, the individual’s working perceptions of what one does in a museum in general and this museum in particular are reinforced and/or reshaped. Through communications with others the individual helps to influence not only his or her own understanding of museums, but the broader community’s perceptions as well. These two types of meanings and understanding flow back into the basic model described above. Past museum visit experiences shape the individual’s future museum visits as well as contributing to other potential visitors’ future visits through input into the broader publics’ understanding of what museums afford.

Although the general patterns of a visit are predictable as outlined above, the details of each visitor’s experience is highly personalized and unique. A graphic representation of this model is depicted on the facing page.

THE MODEL AT WORK

We can see how this basic model plays out by dissecting the experience of another visitor to the California Science Center, a 40-year-old college educated (history degree) white woman who we’ll call Susan. On the particular day we observed Susan, it was a weekday and she was in town visiting her parents along with her three children. The excerpts below are from a series of interviews and observations with Susan that occurred both at the time of her visit (the initial interview occurred at the threshold of the World of Life permanent exhibition) and again, eighteen months after her visit.

The Museum Visitor Experience and the Role of Identity-Related Visit Motivations.

Q: |

Tell me about why you decided to visit the Science Center today. Whose idea was it to visit today? |

A: |

I did [decide]. My parents like to do things with the family, so we were spending the week with them so we sort of decided this week to go [to the Science Center]. My kids are out of school and we are spending the week with [my parents] and my husband is traveling so we thought it would be a good time to go. |

Q: |

Why the California Science Center? Have you been here before? |

A: |

Because I’ve taken my kids before and they loved it. |

Q: |

What about your parents? |

A: |

They haven’t been in a long time and I thought it would be fun for them to see it and they showed interest in going. |

Q: |

Since you have been here before and it was your idea to come today, what are you hoping will happen? What’s your goal for the visit? |

A: |

Well, I guess I just want to have fun with my kids and parents, but I also want them to learn something. |

Q: |

Sure, that makes sense. But tell me more about what would be fun for you and what kinds of things do you think you want your children to learn. |

A: |

What will be fun for me is if my children enjoy themselves and enjoy being with their grandparents. I also want the kids to learn something, that they’ll see some things that will help them in school and generally in their life. |

Q: |

Great, tell me more about what you want your children to see and do. |

A: |

I want them to see the chicks, and the smoking and hand-washing exhibits [all in the World of Life exhibition]. |

Q: |

Well, that’s interesting. Why those exhibits? |

A: |

The chicks will help them learn about birth and development and caring for life. The smoking and hand-washing exhibits will help them learn important things for staying healthy. But speaking of that, I’ve got to ask if I can go now. I’ve got to catch up with my kids and make sure my parents are okay. |

We can see that already when Susan entered the exhibition she had a strong sense of purpose for her visit. She describes a situation that includes time away from her husband but in the presence of her parents and her two children. Since her children are out of school and her parents are retired, she perceives her situation as a leisure problem related to finding something that will be suitable to the needs of all parties. Based upon prior experience, Susan realizes that a visit to the California Science Center could satisfy her needs. It is close-by, the children enjoy it and can learn there, and her parents will enjoy watching the children and might also enjoy the content of the museum. She decides that it will be the perfect solution, and we can infer that she successfully “sold” the idea to her children and parents. We can also infer that her children probably did enjoy themselves on their previous visit so were easily persuaded to revisit.

Although Susan made the decision to visit the Science Center, she reveals that her decision was aimed almost entirely at supporting and facilitating others—her children and her parents—rather than some personal learning goal or desire. She saw herself acting as the social glue that held this multi-generational group together and the supporter of both her children and her parents. Susan envisioned herself acting as both a good parent and a good child. Susan also makes clear that in addition to her desire to have a fun, social-bonding outing with her children and parents, she also has a general and a specific learning agenda for her children. She has a self-concept of what it means to be a good parent—good parents support their children’s learning, in particular learning things that will be important to them in the future. Using her prior knowledge of the museum, Susan has formed a visit goal that includes interacting with three specific exhibits; each has an educational message she hopes her children will learn. She enters the Science Center with a suite of identity-related motivations characteristic of Facilitators.

In the World of Life Exhibition

The Visit After the entry interview, Susan catches up with her parents and children who have stayed together at the urging of Susan’s mother. They have not proceeded too far into the exhibition, drifting off towards the right side of the space. With Susan back “in charge” the group loosens up. “In charge” is actually not an apt description of how Susan allowed this visit to unfold. She basically held back and chatted with her parents while her children moved from one exhibit to another. Only occasionally and superficially did Susan actually engage with an exhibit. Every now and then she suggested a direction to the children or answered a child’s question. Sometimes, she posed questions herself, but this was not the norm. Most of the time she was content to follow the children around to wherever and whatever attracted their interest.

There were a few exhibits that Susan became engaged with, most notably the Surgery Theater exhibit and the Washing Hands exhibits. The latter she specifically directs her children to view. At these two exhibits Susan actively is involved with her children in viewing, talking, and reading labels. Her parents also become involved with these exhibits offering their comments and thoughts. The children needed no encouragement to stop and watch the chicks hatching; in fact, Susan doesn’t approach the exhibit while the children are there. She hangs back and continues to talk with her parents. Susan also actively directs the children to the Smoking exhibit, although she doesn’t say much while they are there.

As it is a weekday morning, the World of Life exhibition is quite crowded and noisy, primarily because of school fieldtrip groups. On several occasions, the path of Susan and the children through the exhibition seems to be diverted by groups of schoolchildren and their chaperones. On at least two occasions, it appears as if they purposefully change their route in an attempt to avoid crowds of students.

Analysis Overall, Susan and her group spend a little more than 30 minutes in the World of Life exhibition. During the visit the group covers slightly more than half (57%) of the exhibition area. However, Susan is only observed interacting with 12 exhibits—13% of the total exhibits in the exhibition; as noted above, most of these exhibits she interacts with only superficially. By contrast, Susan’s children interact with more than three times the number of exhibits. As is typical of a child-driven visit, Susan’s pathway through the exhibition is not orderly as the children dart from one exhibit to the next.

Susan’s museum behavior follows the pattern of many parents with a Facilitator motivation. Her pathway through the exhibition is child-driven and outwardly random; more of Susan’s time is devoted to social interaction than in looking at and interacting with exhibits. Since Susan had two groups she was trying to facilitate, her children and her parents, she divided her time between them. Her social interactions are mostly directed towards her parents rather than her children. However, at a few exhibits she becomes quite engaged with her children and enters into significant learning-focused social interactions. And at the Surgery Theater, her engagement with the exhibit appeared to be at least equally motivated by her own personal curiosity. There did not appear to be any particular exhibit that Susan stopped at specifically because of her parents. Her parents occasionally also looked at the exhibits in which the children showed interest, but they usually hung back and seemed content to watch the children and now and then, talk with Susan. Overall, Susan appeared quite amenable to allowing her children to enjoy the museum on their own terms. Occasionally, she imposed her own agenda on the group, but mostly she allowed the children to select what they wanted to see and do. It is notable that in important ways, Susan’s museum experience is influenced and shaped by visitors outside her family group; the noise makes it difficult to talk and the crowds force changes in what and how long she and her children can interact with certain exhibits.

Eighteen Months Later

Several things stand out in this visitor recollection. The first is that Susan clearly recalls this visit and in particular, remembers that everyone enjoyed themselves. She makes it clear that she thought this was an important experience for her children and it helped them in their intellectual development. She also indicates that her parents enjoyed the experience and makes the projection that they too learned from the experience. In this way, Susan reveals the strength of her identity-related self-aspects for that day—being a good parent, as well as being a good child herself. Her strongest goal though was helping her children grow and become healthier and happier. She makes a point of stating that the museum visit was not like taking your children to the park; this kind of experience has greater value. Overall, she expresses great satisfaction with her visit to the Science Center.

Her memories of the day support her good-parent narrative as she recalls how her children have a greater appreciation for the dangers of smoking and the importance of hand-washing. In fact, Susan offers evidence that her children not only have a greater appreciation for the importance of hand-washing, but that this appreciation is over and above that of other children. Although she did not actively interact with, or even spend much time watching the chick-hatching exhibit herself, the fact that her children really enjoyed this particular exhibit has great salience for her. Susan was able to share her children’s delight with the exhibit which, in turn, reinforced her self-aspect that she was being a good parent.

Exactly what Susan remembers about the day is also very revealing. She finds it easy to talk about what her children did and what kinds of things they might have learned. When pressed, she indicates that she too enjoyed picking up some information, but she’s quick to point out that this was not really the purpose of the visit. The one exhibit that stood out for Susan in this regard was the surgery exhibit; otherwise she dwells on the exhibits that she particularly wanted the children to see and learn from. In contrast with the depth of her social memories, Susan has few memories of the actual exhibition itself. She is hard-pressed to remember any details of what she specifically saw and did that day at the museum. Also absent from Susan’s recollections are any negative memories such as the noise and crowds of the Science Center; these memories have been swept away by her Facilitator narrative. Again, her interest and needs entering, while in the museum, and then again after the visit, were focused primarily on her children and secondarily on her parents. Because of her Facilitator agenda, Susan was only minimally concerned with her own personal curiosity and interests or even comfort. Her entering Facilitator identity-related motivations created the framework for both her actual visit experiences and her memories of those experiences, and thus formed an overall trajectory for her visit. In sum, Susan had a working model of what the Science Center would afford her and her family—an enjoyable, educational experience—and then ascribed a series of self-aspects to her visit that were consistent with this model—“I’m a good parent who helps my children learn the things they need to live a healthy and successful life.” Susan “enacted” these identity-related self-aspects during her visit to the Science Center. She was rewarded later by feedback from her family that suggested that everyone enjoyed themselves and even learned some things she had hoped they would.

We can see from Susan’s interview after the visit that not only did she have long-term memories of the experience, but that she also used the experience to enhance her self-concept as a good parent:

My expectations would have been that my kids showed interest in science, that they got some information at the same time as being entertained. That it opened some dialogue for us to talk about things we might not talk about normally. That it’s interesting so when I go back and do homework with my kids I can know how to talk with them and get them to learn things. So I guess creating the dialogue is what I look for, too.

Susan believes that good parents encourage interest in subjects like science and they encourage their children’s intellectual growth and curiosity. She also indicates that she believes that good parents are active participants in their children’s learning process; this is not just the role of the schools. These were beliefs Susan likely had prior to her visit to the Science Center, but it’s clear that all of these beliefs were reinforced by her museum visit.

We can also see how Susan’s own adult self-identity was shaped by the visit in her projections about the benefits she believed her parents received from the visit:

Well, they’re interested in it because they probably didn’t have as much science as we had in school and so it’s interesting to them to see it in such a simplistic form. Then they can apply what they’ve learned in their life to that, I guess. They’re just that kind of people that continually learn…. Because it’s fun for adults to get to do things that kids get to do. And they’re retired, they like to go out and do things and they like to learn. And they like to see the kids have fun and they like to read about stuff and see the exhibits. They just kind of enjoy that sort of thing.

Although we didn’t focus our observations on Susan’s parents, the data does not suggest that they actually spent much time looking at and learning from exhibits. However, this perception of her parents was reflected in both her pre-visit expectations and persisted in Susan’s long-term recollections of the experience. For Susan, this view of her parents was reality.

Finally, we can believe that Susan’s prior understanding of what a science center in particular, and museums in general afford family visitors was strengthened by her experiences at the California Science Center. We would not be surprised (though she didn’t offer this information to us) that she communicated to others, both friends and family, about how wonderful the California Science Center is for a family visit. As we can see from this example, visitors do use their identity-related visit motivations to justify their museum visit in advance, to guide their behavior during their museum visit, and to make sense of their museum visit retrospectively.

TRAJECTORIES AND STOCHASTIC MODELS

As described in Chapter 4, I would propose that a model of the museum visitor experience is basically a stochastic model. A stochastic model assumes that “initial states,” for example, a parent’s desire to support their children’s meaningful learning-related experiences and one’s prior knowledge and interest in particular topics, are extremely important. These initial states are then influenced by other factors, for example, the exhibits and objects an individual encounters while visiting a museum and the conversations one has with one’s family group while in the museum, and so on. The basic trajectory of the individual changes over time through interactions with both predictable and unpredictable events. The collective interactions, rather than just the initial state, determine the outcomes. In addition, random events, such as Susan’s misfortune of visiting the Science Center on a busy day, potentially influence and modulate the relative amplitude of impact that the various contextual factors have on the museum visitor experience. This is what is meant by a stochastic model (“stochastic” being a fancy way to say “random” and “unpredictable”); stochastic factors influence both the quality and quantity of experiences that result.

The model postulates that virtually all people who visit museums begin from a relatively common, culturally-shared frame of reference—museums are leisure educational institutions that afford a suite of possible benefits. Depending upon the needs an individual has and his or her perceptions of what a particular museum is likely to afford, the visitor “launches” his or her museum visitor experience following a generalized museum visit “trajectory.” Currently, museums seem to afford five basic types of visit trajectories—Explorer trajectory, Facilitator trajectory, Experience seeker trajectory, Professional/Hobbyist trajectory, and a Recharger trajectory. Although many visitors arrive with some combination of these basic motivational trajectories and some visitors arrive with no strongly-held entering motivations and thus no obvious trajectory, the current evidence would suggest that a majority of visitors enter the museum with a single, dominant visitor motivational trajectory.

Each of the five basic trajectories is, within the limits of our current knowledge, generally predictable. Rechargers and Professional/Hobbyists probably have the “straightest” trajectories. These visitors typically enter with a fairly specific goal in mind, a relatively sophisticated understanding of the physical layout and design of the museum, and a fairly clear sense of how to accomplish their goals. For example, “I came to take pictures of the big cats” or “I’m looking for neat exhibit design ideas that I can use in my own museum.” They can and occasionally do get sidetracked by experiences outside of their initial intentions, but for these two groups, this is the exception rather than the rule. More often than not these visitors make a beeline to the exhibits or spaces they are interested in, spend whatever time it takes to accomplish their goal(s), and then depart. Although they may “graze” upon exiting, this is primarily to take stock of things for their next visit.

By contrast, the trajectories of Explorers and Facilitators are much more generalized and less laser-like. The Explorer is seeking “interesting things” while the Facilitator is seeking “interesting things for others.” What guides the Explorer in this quest is their own inner compass which is “magnetized” by the visitor’s unique prior knowledge, experience, and interests. They can’t tell you what will pique their curiosity before they get there, but once inside the museum, they will know immediately what interests them! At exhibits that strike their fancy, they will spend considerable time and perhaps, even discussing it with their social group, though many Explorers prefer to go alone once in the museum. They’re happy to share what they’ve found but they fear being distracted by someone else’s interests. An Explorer’s journey through the museum is likely to be somewhat wandering, punctuated by periods of intensive looking and pointing at objects, labels and exhibits, as well as times of concentrated conversing with others.

The general approach to the museum is much different for the Facilitator. They, too, have only the most general of goals—to satisfy the needs of someone else and to help maximize the quality of that other person’s experience. Whereas individuals with an Explorer motivation are focused on the physical aspects of the museum, individuals with a Facilitator motivation are primarily attuned to the social aspects of the visit; they are focused on what their significant other finds interesting and enjoyable. Facilitators, like Susan, tend to sublimate their own interests and curiosities unless they feel that by sharing these, they might be helpful in satisfying the needs and interests of others. Return visitors, like Susan, are likely to have some ideas going into the visit about what might be worth seeing and doing, but they are also usually happy to let other members of their social group define for themselves what is worth attending to. Facilitators engage in considerable social interaction within their own social group; visitors like Susan in this chapter and George and Frank in earlier chapters may spend a disproportionate amount of their visit attending to their companions and chatting with them rather than focusing intently on the exhibits. This works just fine for them since this kind of social interaction is why they came in the first place—the museum is a stage setting for this social play to be enacted and the exhibits are mere props. Thus, a Facilitator’s track through the physical space will appear somewhat haphazard, despite being quite purposeful.

Finally, the trajectory of individuals with an Experience-seeker motivation is a blend of the Explorer and the Facilitator. They, too, have a generalized goal for their visit, but rather than satisfying their personal curiosity or the specific intellectual needs of their companions (though both of these are very likely to be strong secondary motivations), the Experience seeking visitor is in search of what is most famous and important in the museum. They have come to see the Hope Diamond or the Mona Lisa, or whatever the museum is most famous for. Most Experience seekers are first-time visitors to the museum and many are relatively infrequent museum visitors. Thus these visitors, unless they receive guidance from the museum, often believe that the best way to see the museum is to start in the first gallery and read every label they encounter. After a while, they realize this strategy is not going to meet their needs so they start picking up the pace and skimming through the museum in an effort to see every exhibit. Those with more savvy will go straight to the icon and then skim through the rest of the institution. Either way, the basic pathway of an Experience seeker is likely to be fairly direct at the beginning of the visit and quite “wobbly” towards the end, as they start walking quickly through halls in an effort to see everything. To date, research seems to suggest that most Experience seekers have multiple motivations—Experience Seeking Facilitators or Experience Seeking Explorers—and thus, tend to enact a “blended” trajectory characteristic of both entering motivations.

As discussed previously, the specifics of what any given visitor is likely to attend to in the museum will depend upon what’s available for them to view, but also it will be based upon the visitor’s own personal interests and understandings and those of their companions. Overall, people tend to use museums to build on and reinforce their own prior knowledge and interests rather than as a vehicle for generating “new” knowledge and interests. The visitors most likely to break out of this mold are individuals with an Explorer motivation, but even these visitors will primarily focus on things that resonate with their pre-existing understanding of the world.

All visitors will be particularly prone to remember those things that struck an emotionally positive chord for them. What’s emotionally positive will of course vary between visitors, but more often than not it will be consistent with their entering identity-related motivations. Explorers will find that ideas and objects that pique their curiosity generate high affect. Facilitators will be looking for their social group to be enjoying themselves; what excites a child or significant other will be highly salient and be remembered. Experience seekers will be attuned to seeing what they were “meant” to see—if they came to see the giant T-Rex, than this will be a real high for them and quite memorable. Professional/Hobbyists will find accomplishment of their personal goals quite satisfying—“I was looking for new ideas and saw a really fabulous use of lighting and scrim which I know I can use back home.” Finally, the Recharger is in search of peace and psychological uplift; if they find this, it will create a sensation of great pleasure and this feeling will remain in memory. Most people’s memories of their museum visitor experience will be framed through the lens of their entering identity-related motivations and the self-aspects they formed to understand personal needs and interests. The details of what the visitor remembers will vary but the basic form and structure of his or her memories is likely to be quite predictable.

In general, we can see that a visitor’s entering identity-related motivation predisposes the visitor to interact with the setting in predictable ways. Once in the setting, the visitor is affected by a whole series of additional factors, some of which are under the control of the institution (e.g., mediation provided by trained staff, orientation brochures and signage, good and bad exhibits, and the nature of interpretation tools such as labels and audio guides). But much of what affects the course of the visitor experience is not directly under the control of the museum such as the prior experience, knowledge, and interests of the visitor and his or her social group. Although these factors are not directly “controlled” by the museum, they can be understood and, at least to a degree, predicted by the museum. Thus, these very critical factors are within the realm of the museum to affect. That’s not to say that there aren’t also unpredictable, often random events that influence the visitor experience over which the museum has less control. These events, such as a crowd standing in front of an important explanatory label that causes the visitor to avoid it, or an accompanying child who suddenly needs to go to the toilet may or may not occur, but when they do, they can strongly influence a visitor’s experience and significantly diminish the predictability of any museum visitor experience outcome. In other words, the basic course of the visitor experience depends in large part on things the museum can predict and thus, plan for and design around. However, there will always be some aspects of the museum visitor experience that are unpredictable and beyond the control of the museum.

Using this model and returning once again to our chapter example of Susan, we can see that once we had a sense of her entering identity-related motivations for visiting the Science Center and knew a few of the details about her prior experiences, interests, and background, we could predict with reasonable accuracy the basic shape and form of her museum visit experience. We could also make some predictions as to what she would likely remember from her visit and even, in general, the meanings she was likely to make from the experience. That’s a lot of useful information to have up front!

This is the basic framework of the model—it suggests that much of the visitor experience is actually knowable and predictable. Accordingly, it is a model that could allow museums to become markedly better at the services they provide to visitors, if we knew what to look for and how to appropriately respond. In the next section of the book, I will introduce some thoughts and suggestions on how these ideas can be applied in practice—ideas for attracting, engaging, and retaining visitors as well as suggestions as to how these ideas could better define and measure the impact of the museum visitor experience.