APPENDIX I

Notes to Chapters

CHAPTER IV

Pages 32 to 33.

In the Samoan classification of relatives two principles, sex and age, are of the most primary importance. Relationship terms are never used as terms of address, a name or nickname being used even to father or mother. Relatives of the same age or within a year or two younger to five or ten years older are classified as of the speaker’s generation, and of the same sex or of the opposite sex. Thus a girl will call her sister, her aunt, her niece, and her female cousin who are nearly of the same age, uso, and a boy will do the same for his brother, uncle, nephew, or male cousin. For relationships between siblings of opposite sex there are two terms, tuafafine and tuagane, female relative of the same age group of a male, and male relative of the same age group of a female. (The term uso has no such subdivisions.)

The next most important term is applied to younger relatives of either sex, the word tei. Whether a child is so classified by an older relative depends not so much on how many years younger the child may be, but rather on the amount of care that the elder has taken of it. So a girl will call a cousin two years younger than herself her tei, if she has lived near by, but an equally youthful cousin who has grown up in a distant village until both are grown will be called uso. It is notable that there is no term for elder relative. The terms uso, tuafafine and tuagane all carry the feeling of contemporaneousness, and if it is necessary to specify seniority, a qualifying adjective must be used.

Tamā, the term for father, is applied also to the matai of a household, to an uncle or older cousin with whose authority a younger person comes into frequent contact and also to a much older brother who in feeling is classed with the parent generation. Tina is used only a little less loosely for the mother, aunts resident in the household, the wife of the matai and only very occasionally for an older sister.

A distinction is also made in terminology between men’s terms and women’s terms for the children. A woman will say tama (modified by the addition of the suffixes tane and fafine, male and female) and a man will say atalii, son and afafine, daughter. Thus a woman will say, “Losa is my tama” specifying her sex only when necessary. But Losa’s father will speak of Losa as his afafine. The same usage is followed in speaking to a man or to a woman of a child. All of these terms are further modified by the addition of the word, moni, real, when a blood sister or blood father or mother is meant. The elders of the household are called roughly matua, and a grandparent is usually referred to as the toa’ina, the “old man” or olamatua, “old woman,” adding an explanatory clause if necessary. All other relatives are described by the use of relative clauses, “the sister of the husband of the sister of my mother,” “the brother of the wife of my brother,” etc. There are no special terms for the in-law group.

CHAPTER V

NEIGHBOURHOOD MAPS

Pages 43 to 46.

For the sake of convenience the households were numbered in sequence from one end of each village to the other. The houses did not stretch in a straight line along the beach, but were located so unevenly that occasionally one house was directly behind another. A schematic linear representation will, however, be sufficient to show the effect of location in the formation of neighbourhood groups.

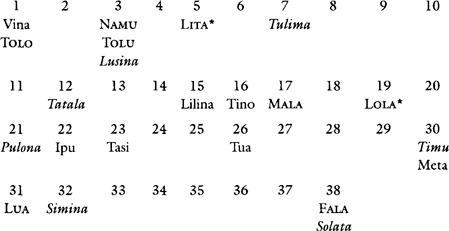

VILLAGE I

Lumā,

(The name of the girl will be placed under the number of the household. Adolescent girls’ names in capitals, girls’ just reaching puberty in lower case and the pre-adolescent children in italics.)

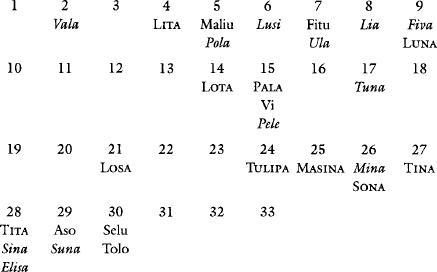

VILLAGE II

Siufaga

(Household 38 in Siufaga is adjacent to household I in Lumā. The two villages are geographically continuous but socially they are separate units.)

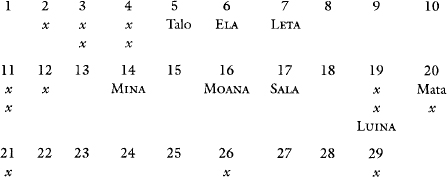

VILLAGE III

Faleasao

(Faleasao was separated from Lumā by a high cliff which jutted out into the sea and made it necessary to take an inland trail to get from one seaside village to the other. This was about a twenty-minute walk from Taū. Faleasao children were looked upon with much greater hostility and suspicion than that which the children of Lumā and Siufaga showed to each other. The pre-adolescent children from this village are not discussed by name and will be indicated by an x.)

CHAPTER IX

Pages 87 to 88.

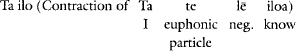

The first person singular of the verb “to know,” used in the negative, has two forms:

and

![]()

The former of these expressions has a very different meaning from the latter although linguistically they represent optional syntactic forms, the second being literally, “I do not know,” while the first can best be rendered by the slang phrase, “Search me.” This “Search me” carries no implication of lack of actual knowledge or information about the subject in question but is merely an indication either of lack of interest or unwillingness to explain. That the Samoans feel this distinction very clearly is shown by the frequent use of both forms in the same sentence: Ta ilo ua lē iloa a’u. “Search me, I don’t know.”

Page 89.

SAMPLE CHARACTER SKETCHES GIVEN OF MEMBERS OF THEIR HOUSEHOLDS BY ADOLESCENT GIRLS (Literal translations from dictated texts)

I

He is an untitled man. He works hard on the plantation. He is tall, thin and dark-skinned. He is not easily angered. He goes to work and comes again at night. He is a policeman. He does work for the government. He is not filled with unwillingness. He is attractive looking. He is not married.

II

She is an old woman. She is very old. She is weak. She is not able to work. She can only remain in the house. Her hair is black. She is fat. She has elephantiasis in one leg. She has no teeth. She is not irritable. She does not hate. She is clever at weaving mats, fishing baskets and food trays.

III

She is strong and able to work. She goes inland. She weeds and makes the oven and picks breadfruit and gathers paper mulberry bark. She is kind. She is of good conduct. She is clever at weaving baskets and mats and fine mats and food trays, and painting tapa cloth and scraping and pounding and pasting paper mulberry bark. She is short, black-haired and dark-skinned. She is fat. She is good. If any one passes by she is kindly disposed towards them and calls out, “Po’o fea ’e te maliu i ai?” (a most courteous way of asking, “Where are you going?”)

IV

She is fat. She has long hair. She is dark-skinned. She is blind in one eye. She is of good behaviour. She is clever at weeding taro and weaving floor mats and fine mats. She is short. She has borne children. There is a baby. She remains in the house on some days and on other days she goes inland. She also knows how to weave baskets.

V

He is a boy. His skin is dark. So is his hair. He goes to the bush to work. He works on the taro plantation. He likes every one. He is clever at weaving baskets. He sings in the choir of the young men on Sunday. He likes very much to consort with the girls. He was expelled from the pastor’s house.

VI

Portrait of herself

I am a girl. I am short. I have long hair. I love my sisters and all the people. I know how to weave baskets and fishing baskets and how to prepare paper mulberry bark. I live in the house of the pastor.

VII

He is a man. He is strong. He goes inland and works upon the plantation of his relatives. He goes fishing. He goes to gather cocoanuts and breadfruit and cooking leaves and makes the oven. He is tall. He is dark-skinned. He is rather fat. His hair is short. He is clever at weaving baskets. He braids the palm leaf thatching mats for the house.* He is also clever at house-building. He is of good conduct and has a loving countenance.

VIII

She is a woman. She can’t work hard enough (to suit herself). She is also clever at weaving baskets and fine mats and at bark cloth making. She also makes the ovens and clears away the rubbish around the house. She keeps her house in fine condition. She makes the fire. She smokes. She goes fishing and gets octopuses and tu’itu’i (sea eggs) and comes back and eats them raw. She is kind-hearted and of loving countenance. She is never angry. She also loves her children.

IX

She is a woman. She has a son, ________ is his name. She is lazy. She is tall. She is thin. Her hair is long. She is clever at weaving baskets, making bark cloth and weaving fine mats. Her husband is dead. She does not laugh often. She stays in the house some days and other days she goes inland. She keeps everything clean. She lives well upon bananas. She has a loving face. She is not easily out of temper. She makes the oven.

X

She is the daughter of ________. She is a little girl about my age. She is also clever at weaving baskets and mats and fine mats and blinds and floor mats. She is good in school. She also goes to get leaves and breadfruit. She also goes fishing when the tide is out. She gets crabs and jelly fish. She is very loving. She does not eat up all her food if others ask her for it. She shows a loving face to all who come to her house. She also spreads foods for all visitors.

XI

Portrait of herself

I am clever at weaving mats and fine mats and baskets and blinds and floor mats. I go and carry water for all of my household to drink and for others also. I go and gather bananas and breadfruit and leaves and make the oven with my sisters. Then we (herself and her sisters) go fishing together and then it is night.

CHAPTER X

Page 93.

The children of this age already show a very curious example of a phonetic self-consciousness in which they are almost as acute and discriminating as their elders. When the missionaries reduced the language to writing, there was no k in the language, the k positions in other Polynesian dialects being filled in Samoan either with a t or a glottal stop. Soon after the printing of the Bible, and the standardisation of Samoan spelling, greater contact with Tonga introduced the k into the spoken language of Savai’i and Upolu, displacing the t, but not replacing the glottal stop. Slowly this intrusive usage spread eastward over Samoa, the missionaries who controlled the schools and the printing press fighting a dogged and losing battle with the less musical k. To-day the t is the sound used in the speech of the educated and in the church, still conventionally retained in all spelling and used in speeches and on occasions demanding formality. The Manu’a children who had never been to the missionary boarding schools, used the k entirely. But they had heard the t in church and at school and were sufficiently conscious of the difference to rebuke me immediately if I slipped into the colloquial k, which was their only speech habit, uttering the t sound for perhaps the first time in their lives to illustrate the correct pronunciation from which I, who was ostensibly learning to speak correctly, must not deviate. Such an ability to disassociate the sound used from the sound heard is remarkable in such very young children and indeed remarkable in any person who is not linguistically sophisticated.

CHAPTER XI

Page 113.

During six months I saw six girls leave the pastor’s establishment for several reasons: Tasi, because her mother was ill and she, that rare phenomenon, the eldest in a biological household, was needed at home; Tua, because she had come out lowest in the missionaries’ annual examination which her mother attributed to favouritism on the part of the pastor; Luna, because her stepmother, whom she disliked, left her father and thus made her home more attractive and because under the influence of a promiscuous older cousin she began to tire of the society of younger girls and take an interest in love affairs; Lita, because her father ordered her home, because with the permission of the pastor, but without consulting her family, she went off for a three weeks’ visit in another island. Going home for Lita involved residence in the far end of the other village, necessitating a complete change of friends. The novelty of the new group and new interests kept her from in any way chafing at the change. Sala, a stupid idle girl, had eloped from the household of the pastor.