CHAPTER FOUR

CONSTRUCTIVE CONTROVERSY

The Value of Intellectual Opposition

David W. Johnson

Roger T. Johnson

Dean Tjosvold

Since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinion that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied.

—John Stuart Mill

An airline flight crew is taking its large passenger jet with over 150 people on board in for a landing. The instruments indicate the plane is still five thousand feet above the ground, and the pilot sees no reason to doubt their accuracy. The copilot thinks the instruments are malfunctioning and the plane is actually much lower. Will this disagreement endanger the passengers and crew by distracting the pilot and copilot from their duties? Or will it illuminate a problem and increase the safety of everyone on board?

We know what Thomas Jefferson would have said. He noted, “Difference of opinion leads to inquiry, and inquiry to truth.” Jefferson had a deep faith in the value and productiveness of constructive controversy. He is not alone. Conflict theorists of many persuasions have posited that conflict could have positive as well as negative benefits. Freud, for example, indicated that extra psychic conflict was a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for psychological development. Developmental psychologists have proposed that disequilibrium within a student’s cognitive structure can motivate a shift from egocentrism to accommodation of the perspectives of others and what results is a transition from one stage of cognitive and moral reasoning to another. Motivational theorists believe that conceptual conflict can create epistemic curiosity, which motivates the search for new information and the reconceptualization of the knowledge one already has. Organizational theorists insist that higher-quality problem solving depends on constructive conflict among group members. Cognitive psychologists propose that conceptual conflict may be necessary for insight and discovery. Educational psychologists indicate that conflict can increase achievement. Karl Marx believed that class conflict was necessary for social progress. From almost every social science, theorists have taken the position that conflict can have positive as well as negative outcomes.

Despite all the theorizing about the positive aspects of conflict, there has been until recently very little empirical evidence demonstrating that the presence of conflict can be more constructive than its absence. Guidelines for managing conflicts tend to be based more on folk wisdom than on validated theory. Far from being encouraged and structured in most interpersonal and intergroup situations, conflict tends to be avoided and suppressed. Creating conflict to capitalize on its potential positive outcomes tends to be the exception, not the rule. In the late 1960s, therefore, building on the previous work of Morton Deutsch and others, we began a program of theorizing and research to identify the conditions under which conflict results in constructive outcomes. One of the results of our work is the theory of constructive controversy.

This chapter provides an integration of theory, research, and practice on constructive controversy for individuals who wish to deepen their understanding of conflict and how to manage it constructively. The first part of the chapter provides the definitions and procedure and a theoretical framework that illuminates fundamental processes involved in creating and using conflict at the interpersonal, intergroup, organizational, and international levels. The second half of the chapter is aimed at helping readers use constructive controversy effectively in their applied situations.

WHAT IS CONSTRUCTIVE CONTROVERSY?

The best way ever devised for seeking the truth in any given situation is advocacy: presenting the pros and cons from different, informed points of view and digging down deep into the facts.

—Harold S. Geneen, Former CEO, ITT

Constructive controversy exists when one person’s ideas, information, conclusions, theories, and opinions are incompatible with those of another and the two seek to reach an agreement. Constructive controversies involve what Aristotle called deliberate discourse (i.e., the discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of proposed actions) aimed at synthesizing novel solutions (i.e., creative problem solving). Related to controversy is cognitive conflict, which occurs when incompatible ideas exist simultaneously in a person’s mind or when information being received does not seem to fit with what one already “knows” (Johnson and Johnson, 2007).

Structured constructive controversies are most commonly contrasted with concurrence seeking, debate, and individualistic learning. Concurrence seeking occurs when members of a group inhibit discussion to avoid any disagreement or arguments, emphasize agreement, and avoid realistic appraisal of alternative ideas and courses of action. Concurrence seeking is close to Janis’s (1982) concept of groupthink , when members of a decision-making group set aside their doubts and misgivings about whatever policy is favored by the emerging consensus so as to be able to concur with the other members. Debate exists when two or more individuals argue positions that are incompatible with one another and a judge declares a winner on the basis of who presented his or her position the best. An example of debate is when each member of a group is assigned a position as to whether more or fewer regulations are needed to control hazardous wastes and an authority declares as the winner the person who makes the best presentation of his or her position to the group. Individualistic efforts exist when individuals work alone without interacting with each other, in a situation in which their goals are unrelated and independent from each other (Johnson, Johnson, and Holubec, 2008). The meta-analysis that follows compares these four forms of conflict. First, however, we review the theory of constructive controversy.

CONSTRUCTIVE CONTROVERSY THEORY

There is no more certain sign of a narrow mind, of stupidity, and of arrogance, than to stand aloof from those who think differently from us.

—Walter Savage Landor

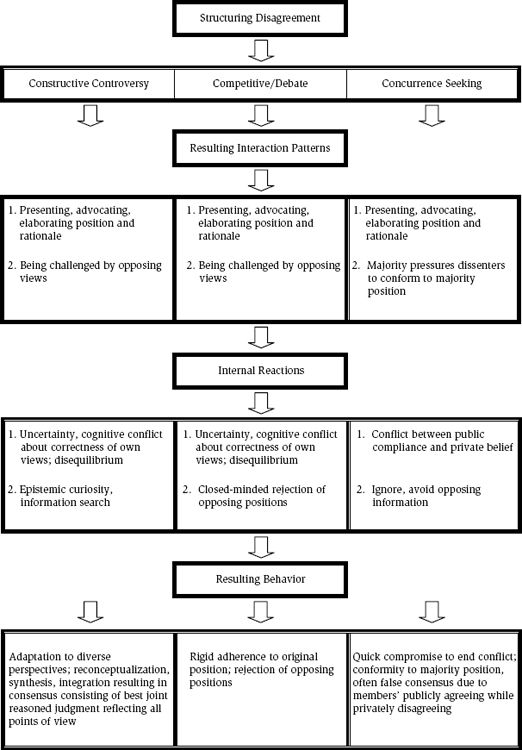

Structure-process-outcome theory (Watson and Johnson, 1972) posits that the structure of the situation determines the process of interaction, and the process of interaction determines the outcomes (e.g., attitudes and behaviors of the individuals involved). The way in which a controversy is structured in learning and decision-making situations determines how group members interact with each other, which in turn determines the quality of the learning, decision making, creativity, and other relevant outcomes. Conflict among group members’ ideas, opinions, theories, and conclusions may be structured along a continuum (Johnson and Johnson, 2007) with constructive controversy at one end and concurrence seeking at the other (see table 4.1 and figure 4.1 ).

Table 4.1 Process of Controversy and Concurrence Seeking

Source: Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2007). Creative Controversy: Intellectual Challenge in the Classroom . Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company. Reprinted by permission.

| Controversy | Concurrence Seeking |

| Organizing what is known into an initial conclusion | Organizing what is known into an initial conclusion |

| Presenting, advocating, elaborating at least two positions and rationale | Presenting, advocating, elaborating dominant position and rationale |

| Being challenged by opposing views, which results in conceptual conflict and uncertainty about the correctness of one’s own views | Majority pressures dissenting group members to conform to majority position and perspective, creating a conflict between public compliance and private belief |

| Conceptual conflict, uncertainty, disequilibrium result | Conflict between public and private position |

| Epistemic curiosity motivates active search for new information and perspectives | Seeking confirming information that strengthens and supports the dominant position and perspective |

| Reconceptualization, synthesis, integration resulting in consensus consisting of best joint reasoned judgment reflecting all points of view | Consensus on majority position—often false consensus due to members’ publicly agreeing while privately disagreeing |

Figure 4.1 Theory of Controversy

Source: Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2007) Creative Controversy: Intellectual Challenge in the Classroom . Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company. Reprinted by permission.

Structure of the Situation

The structure of the situation contains the role definitions and normative expectations that define appropriate and inappropriate ways for individuals to interact with each other in the situation, as well as other situational influences, such as the number of people involved, spatial arrangements, hierarchy of prestige, social sanctions, power, and the nature of activities to be conducted (Watson and Johnson, 1972). Changes in any or all of these factors lead to changes in the processes of the system and the interactions of the members, which subsequently change the attitudes and behavior and the other outcomes of the individuals involved.

Structuring Constructive Controversy.

In constructive controversy, individuals research their position, present the best case they can for it, challenge the opposing positions, step back and see the issue from all sides, and then arrive at their best reasoned judgment. Constructive controversy is structured by

- Establishing a cooperative contex t (i.e., structuring positive interdependence). Participants to come to an agreement (i.e., one answer) that reflects their best reasoned judgment as to solution to the problem, the best course of action to take to solve the problem, or an answer.

- Establishing the constructive controversy procedure . Participants are required to (1) research and prepare a position; (2) present and advocate their position; (3) analyze, critically evaluate, and (often after further research) refute the opposing positions while rebutting criticisms of one’s own positions; (4) reverse perspectives to communicate that they can see the issue from all points of view; and (5) synthesize and integrate information into factual and judgmental conclusions that are summarized into a joint position to which all sides can agree (Johnson and Johnson, 2007). This is an advocacy-based-inquiry procedure. In engaging in this procedure, participants advocate a position and challenge opposing positions to gain increased understanding of the issue so that an agreement reflecting their best reasoned judgment can be made. here is a reliance on argumentative clash to develop, clarify, expand, and elaborate one’s thinking about the issues being considered. Advocacy and critically challenging the opposing positions are key elements in engaging in inquiry to discover the best course of action.

- There are a number of roles that each participant needs to assume adequately: researcher, advocate, devil’s advocate, learner, perspective taker, and synthesizer. Participants need to be effective advocates, persuasively presenting the best case possible for their positions. Participants also need to be effective devil’s advocates, critically analyzing opposing positions, pointing out their weaknesses and flaws in information and logic. No position should be unchallenged. Participants need to be able to learn thoroughly the opposing positions and their rationales. This facilitates their critical analysis as devil’s advocates, but also facilities their performance of the role of perspective taker. Finally, participants need to be effective synthesizers, integrating the best information and logic from all positions into a new, novel position that all participants can agree to.

- Participants need to adhere to a set of normative expectations . Participants need to follow and internalize the norms of seeking the best reasoned judgment, not winning; being critical of ideas, not people; listening to and learning everyone’s position, even if they do not agree with it; differentiating positions before trying to integrate them; and changing their mind when logically persuaded to do so.

Structuring Concurrence Seeking.

In concurrence seeking, individuals present their position and its rationale. If it differs from the dominant opinion, the dissenters are pressured by the majority of members to conform to the dominant opinion; if the dissenters do not, they are viewed as nonteam players who obstruct team effectiveness and therefore subjected to ridicule, rejection, ostracism, and being disliked (see Johnson and Johnson, 2007). If they concur, they often seek out confirming information to strengthen the dominant position and view the issue only from the majority’s perspective, thus eliminating the possible consideration of divergent points of view. Thus, there is a convergence of thought and a narrowing of focus in members’ thinking. A false consensus results, with all members agreeing about the course of action the group is to take, while privately some members may believe that other courses of action would be more effective. Concurrence seeking is structured in these ways:

- A cooperative context is established (i.e., structuring positive interdependence). Participants are to come to an agreement based on the dominant position in the group.

- The concurrence-seeking procedure is established . The dominant position is determined, and all participants are encouraged to agree with it. Both advocacy of opposing positions and critical analysis of the dominant position are avoided. Participants are to “be nice” and not disagree with the dominant position. Doubts and misgivings are to be hidden and outward conformity in supporting the dominant position, whether you believe in it or not, is encouraged.

- There are a number of roles that each participant needs to assume adequately: Supporter, persuader. Participants need to be supporters of the dominant position and persuaders of dissenters to adopt the dominant position.

- There is a set of normative expectations that participants need to adhere to . Participants need to follow and internalize the norms of hiding doubts and criticisms about the dominant position, being willing to quickly compromise to avoid open disagreement, expressing full support for the dominant position, never disagreeing with other group members, and maintaining a harmonious atmosphere.

PROCESSES OF INTERACTION

Constructive controversy and concurrence seeking promote different processes of interaction among individuals, which in turn promote different outcomes (Johnson and Johnson, 1979, 1989, 2000, 2003, 2007, 2009; Johnson, Johnson, and Johnson, 1976) (see table 4.1 and figure 4.1 ).

Constructive Controversy

The process through which constructive controversy creates positive outcomes involves the following theoretical assumptions:

- When individuals are presented with a problem or decision, they have an initial conclusion based on categorizing and organizing incomplete information, their limited experiences, and their specific perspective. They have a high degree of confidence in their conclusions (i.e., they freeze the epistemic process).

- When individuals present and advocate positions to others (who are advocating opposing positions), they engage in cognitive rehearsal, deepen their understanding of their position, and use higher-level reasoning strategies. The more they attempt to persuade others to agree with them, the more committed they may become to their position. The intent is to convert the other group members to one’s position. Knowing that the presenting individual is trying to convert them, the other individuals involved may scrutinize the person’s position and critically analyze it as part of their resistance to being converted. Hearing opposing views being advocated stimulates new cognitive analysis and frees individuals to create alternative and original conclusions. Even being confronted with an erroneous point of view can result in more divergent thinking and the generation of novel and more cognitively advanced solutions because they unfreeze the epistemic process.

- When individuals challenge the positions of opposing advocates, they attempt to refute opposing positions while rebutting attacks on their own position. To do so, they critically analyze one another’s positions in attempts to discern weaknesses and strengths. Individuals tend to evaluate information more critically. In other words, dissenters tend to stimulate divergent thinking and the consideration of multiple perspectives. Members start with the assumption that the dissenter is not correct. If a dissenter persists, however, it suggests a complexity that stimulates a reappraisal of the issue. The reappraisal, often including additional information, involves divergent thinking and a consideration of multiple sources of information and ways of thinking about the issue. It also breaks the tendency of groups to try to achieve consensus before all available alternatives have been thoroughly considered. On balance, challenging and being challenged tend to increase knowledge and understanding, the creativity of thinking, and the quality of decision making.

- When individuals are confronted with different conclusions based on other people’s information, experiences, and perspectives, they become uncertain as to the correctness of their own views, and a state of conceptual conflict or disequilibrium is aroused. Hearing other alternatives being advocated, having one’s position criticized and refuted, and being challenged by information that is incompatible with and does not fit with one’s conclusions leads to conceptual conflict, disequilibrium, and uncertainty. The greater the disagreement among group members, the more frequently disagreement occurs, the greater the number of people disagreeing with a person’s position, the more competitive the context of the controversy, and the more affronted the person feels, the greater the conceptual conflict, disequilibrium, and uncertainty the person experiences.

- When individuals are faced with intellectual opposition within a cooperative context, they tend to ask one another for more information, seek to view the information from all sides of the issue, and use more ways of looking at facts. Conceptual conflict motivates an active search (called epistemic curiosity ) for more information and new experiences (increased specific content) and a more adequate cognitive perspective and reasoning process (increased validity) in hopes of resolving the uncertainty. Indexes of epistemic curiosity include individuals’ actively searching for more information, seeking to understand opposing positions and rationales, and attempting to view the situation from opposing perspectives.

- By adapting their cognitive perspective and reasoning through understanding and accommodating new information as well as the perspective and reasoning of others, individuals derive a new, reconceptualized, and reorganized conclusion. Novel solutions and decisions that on balance are qualitatively better are detected. The positive feelings and commitment of individuals as they create a solution to the problem together is extended to each other, and interpersonal attraction increases. A bond is built among the participants. Their competencies in managing conflicts constructively tend to improve. The process may begin again at this point, or it may be terminated by freezing the current conclusion and resolving any dissonance by increasing confidence in the validity of the conclusion.

When overt controversy is structured by identifying alternatives and assigning members to advocate the best case for each alternative, the purpose is not to choose one of the alternatives. Rather, is to create a synthesis of the best reasoning and conclusions from all the alternatives. Synthesizing occurs when individuals integrate a number of different ideas and facts into a single position. It is the intellectual bringing together of ideas and facts and engaging in inductive reasoning by restating a large amount of information into a conclusion or summary. Synthesizing is a creative process that involves seeing new patterns within a body of evidence, viewing the issue from a variety of perspectives, and generating a number of optional ways of integrating the evidence. This requires probabilistic (i.e., knowledge is available only in degrees of certainty) rather than dualistic (i.e., there is only right and wrong and authority should not be questioned) or relativistic thinking (i.e., authorities are seen as sometimes right but right and wrong depend on your perspective). The dual purposes of synthesis are to arrive at the best possible decision and find a position that all group members can commit themselves to implement. When consensus is required for decision making, the dissenting members tend to maintain their position longer, the deliberation tends to be more robust, and group members tend to feel that justice has been better served.

Concurrence Seeking

The process through which concurrence seeking creates outcomes involves the following theoretical assumptions (Johnson and Johnson, 2007) (see figure 4.1 ):

- When faced with a problem to be solved or a decision to be made, the group member with the most power (i.e., the boss) or the majority of the members derive an initial position from their analysis of the situation based on their current knowledge, perspective, dominant response, expectations, and past experiences. They tend to have a high degree of confidence in their initial conclusion (they freeze the epistemic process).

- The dominant position is presented and advocated by the most powerful member in the group or a representative of the majority. It may be explained in detail or briefly, as it is expected that all group members will quickly agree and adopt the recommended position. When individuals present their conclusion and its rationale to others, they engage in cognitive rehearsal and often reconceptualize their position as they speak. In addition, their commitment to their position increases, making them more closed-minded toward other positions.

- Members are faced with the implicit or explicit demand to concur with the recommended position. The pressure to conform creates evaluation apprehension that implies that members who disagree will be perceived negatively and rejected. Conformity pressure is also used to prevent members from suggesting new ideas, thereby stifling creativity. The dominant person or the majority of the members tend to impose their perspective about the issue on the other group members, so that all members view the issue from the dominant frame of reference, resulting in a convergence of thought and a narrowing of focus in members’ thinking.

- When a member does not agree with the recommended position, he or she has a choice: concur with the majority opinion or voice dissent and face possible ridicule, rejection, ostracism, and being disliked. This creates a conflict between public compliance and private belief, which can create considerable distress when the dissenter keeps silent, and perhaps even more stress when the dissenter voices his or her opinion. Dissenters realize that if they persist in their disagreement, they may be viewed negatively and will be disliked and isolated by both their peers and their supervisors, or a destructively managed conflict may result that will split the group into hostile factions, or both. Because of these potential penalties, many potential dissenters find it easier to remain silent and suppress their true opinions.

- Members concur publicly with the dominant position and its rationale without critical analysis. In addition, they seek supporting evidence to strengthen the dominant position and view the issue only from the dominant perspective, thus eliminating the possible consideration of divergent points of view. Dissenters may adopt the majority position either because they assume that truth lies in numbers (i.e., the majority is probably correct) or they fear that disagreeing openly will result in ridicule and rejection. They also search for information in a biased manner to confirm the majority position. As a result, they are relatively unable to detect original solutions to problems.

- All members agree about the course of action the group is to take. while some members privately may believe that other courses of action would be more effective.

Benefits of Constructive Controversy

He that wrestles with us strengthens our nerves, and sharpens our skill. Our antagonist is our helper.

—Edmund Burke, Reflection of the Revolution in France

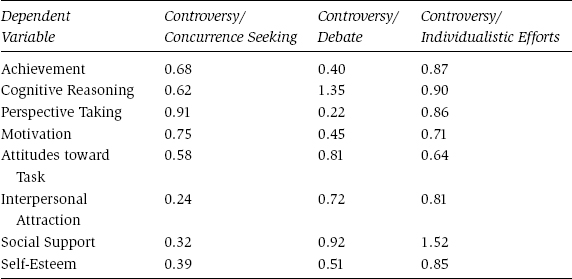

The research on constructive controversy has been conducted over the past thirty-five years by several researchers in a variety of settings using many different participant populations and many different tasks within an experimental and field experimental format (see table 4.2 ). (For a detailed listing of all the supporting studies, see Johnson and Johnson, 1979, 1989, 2000, 2003, 2007, 2009.) All studies randomly assigned participants to conditions. The studies have all been published in journals (except for one dissertation), have high internal validity, and have lasted from one to sixty hours. The studies have been conducted on elementary, intermediate, and college students. Taken together, their results have considerable validity and generalizability. A recent meta-analysis provides the data to validate or disconfirm the theory (Johnson and Johnson, 2007).

Table 4.2 Meta-Analysis of Academic Controversy Studies: Weighted Effect Sizes

Source: Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (2007). Creative controversy: Intellectual conflict in the classroom. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company. Reprinted with permission

Quality of Decision Making, Problem Solving, and Learning.

Effective decision making and problem solving includes higher-level reasoning, accurate understanding of all perspectives, creative thinking, and openness to influence (i.e., attitude change). Compared with concurrence seeking (ES = 0.68), debate (ES = 0.40), and individualistic efforts (ES = 0.87), constructive controversy tends to result in higher-quality decisions (including decisions that involve ethical dilemmas) and higher-quality solutions to complex problems for which different viewpoints can plausibly be developed. Skillful participation in a constructive controversy tends to result in significantly greater mastery and recall of the information, reasoning, and skills contained in one’s own and others’ positions; more skillfully transferring of this learning to new situations; and greater generalization of principles learned to a wider variety of situations than do concurrence seeking, debate, or individualistic efforts. Being exposed to a credible alternative view results in recalling more correct information, more skillfully transferring learning to new situations, and generalizing the principles they learned to a wider variety of situations. The resolution of a controversy is likely to be in the direction of correct problem solving even when the initial conclusions of all group members are erroneous and especially when individuals are exposed to a credible minority view (as opposed to a consistent single view) even when the minority view is incorrect.

An interesting question is whether the advocacy of two conflicting but wrong solutions to a problem can result in a correct solution. The value of the constructive controversy process lies not so much in the correctness of an opposing position as in the attention and thought processes it induces. More cognitive processing may take place when individuals are exposed to more than one point of view, even if one or more of the points of view is incorrect. A number of studies with both adults and children have found significant gains in performance when erroneous information is presented by one or both sides in a constructive controversy. Thus, the resolution of the conflict is likely to be in the direction of correct performance. In this limited way, two wrongs came to make a right.

Cognitive Reasoning.

When difficult issues are being discussed and effective decisions are needed, higher-level reasoning strategies are needed. Controversy tends to promote more frequent use of higher-level reasoning strategies than do concurrence seeking (ES = 0.62), debate (ES = 1.35) or individualistic efforts (ES = 0.90). For example, controversy tends to be more effective than modeling and nonsocial presentation of information in influencing nonconserving children to gain the insights critical for conservation. In classrooms where students are free to dissent and are also expected to listen to different perspectives, students tend to think more critically about civic issues and be more tolerant of conflicting views. Thus, cognitive reasoning across domains of inquiry is improved when controversy is used.

Perspective Taking.

Understanding and considering all perspectives is important if difficult issues are to be discussed, the decision is to represent the best reasoned judgment of all participants, and all participants are to help implement the decision. Constructive controversy tends to promote more accurate and complete understanding of opposing perspectives than do concurrence seeking (ES = 0.91), debate (ES = 0.22), and individualistic efforts (ES = 0.86). Engaging in controversy tends to result in greater understanding of another person’s cognitive perspective than does the absence of controversy, and individuals engaged in a controversy tend to be better able subsequently to predict what line of reasoning their opponent would use in solving a future problem than do individuals who interacted without any controversy. The increased understanding of opposing perspectives tends to result from engaging in controversy (as opposed to engaging in concurrence-seeking discussions or individualistic efforts) regardless of whether one is a high-, medium-, or low-achieving student.

Creativity.

Constructive controversy tends to promote creative insight by influencing individuals to view problems from different perspectives and reformulate problems in ways that allow the emergence of new orientations to a solution. Compared with concurrence seeking, debate, and individualistic efforts, constructive controversy increases the number of ideas, quality of ideas, creation of original ideas, the use of a wider range of ideas, originality, the use of more varied strategies, and the number of creative, imaginative, novel solutions. Being confronted with credible alternative views has resulted in the generation of more novel solutions, varied strategies, and original ideas. Participants in a constructive controversy tend to have a high degree of emotional involvement in and commitment to solving the problems the group was working on.

Attitude Change about the Issue.

Open-minded consideration of all points of view is critical for deriving well-reasoned decisions that integrate the best information and thought from a variety of positions. Participants should open-mindedly believe that opposing positions are based on legitimate information and logic that, if fully understood, will lead to creative solutions that benefit everyone. Involvement in a controversy tends to result in attitude and position change. Participants in a controversy tend to reevaluate their attitudes about the issue and incorporate opponents’ arguments into their own attitudes. Participating in a constructive controversy tends to result in attitude change beyond what occurs when individuals read about the issue, and these attitude changes tend to be relatively stable over time (i.e., not merely a response to the controversy experience itself).

Motivation to Improve Understanding.

Effective decision making is typically enhanced by a continuing motivation to learn more about the issues being considered. Most decisions are temporary because they may be reconsidered at some future date. Participants in a constructive controversy tend to have more continuing motivation to learn about the issue and come to the best reasoned judgment possible than do participants in concurrence seeking (ES = 0.75), debate (0.45), and individualistic efforts (ES = 0.71). Participants in a controversy tend to search for more information and new experiences (increased specific content) and a more adequate cognitive perspective and reasoning process (increased validity) in hopes of resolving the uncertainty. There is also an active interest in learning the others’ positions and developing an understanding and appreciation of them. Lowry and Johnson (1981), for example, found that students involved in a controversy, compared with students involved in concurrence seeking, read more library materials, reviewed more classroom materials, more frequently watched an optional movie shown during recess, and more frequently requested information from others. Generally motivation is increased by participating in a constructive controversy.

Attitudes toward Controversy.

If participants are to be committed to implement the decision and participate in future decision making, they must react favorably to the way decisions are made. Individuals involved in controversy liked the procedure better than did those working individualistically, and participating in a controversy consistently promoted more positive attitudes toward the experience than did participating in a debate, concurrence-seeking discussions, or individualistic decisions. Constructive controversy experiences promoted stronger beliefs that controversy is valid and valuable.

Attitudes toward Decision Making.

If participants are to be committed to implement the decision and participate in future decision making, they must consider the decision worth making. Individuals who engaged in controversies tended to value the decision-making task more than did individuals who engaged in concurrence-seeking discussions (ES = 0.63).

Interpersonal Attraction and Support among Participants.

Decision making, to be effective, must be conducted in ways that bring individuals together rather than create ill will and divisiveness. Within controversy, disagreement, argumentation, and rebuttal could create difficulties in establishing good relationships. Constructive controversy, however, has been found to promote greater liking among participants than did debate (ES = 0.72), concurrence seeking (ES = 0.24), or individualistic efforts (ES = 0.81). Debate tended to promote greater interpersonal attraction among participants than did individualistic efforts (ES = 0.46). In addition, constructive controversy tends to promote greater social support among participants than does debate (ES = 0.92), concurrence seeking (ES = 0.32), or individualistic efforts (ES = 1.52). Debate tended to promote greater social support among participants than did individualistic efforts (ES = 0.92). The combination of frank exchange of ideas coupled with a positive climate of friendship and support not only leads to more productive decision making and greater learning, it disconfirms the myth that conflict inevitably leads to divisiveness and dislike.

Self-Esteem.

Participation in future decision making is enhanced when participants feel good about themselves as a result of helping make the current decision, whether or not they agree with it. Constructive controversy tends to promote higher self-esteem than does concurrence seeking (ES = 0.39), debate (ES = 0.51), or individualistic efforts (ES = 0.85). Debate tends to promote higher self-esteem than individualistic efforts do (ES = 0.45).

Conditions Determining the Constructiveness of Controversy

Although controversies can operate in a beneficial way, they will not do so under all conditions. Whether controversy results in positive or negative consequences depends on the conditions under which it occurs and the way in which it is managed. These conditions include the context within which the constructive controversy takes place, the heterogeneity of participants, the distribution of information among group members, the level of group members’ social skills, and group members’ ability to engage in rational argument (Johnson and Johnson, 1979, 1989, 2007).

Cooperative Goal Structure.

Deutsch (1973) emphasizes that the context in which conflicts occur has important effects on whether the conflict turns out to be constructive or destructive. There are two common contexts for controversy: cooperative and competitive. A cooperative context tends to facilitate constructive controversy, whereas a competitive context tends to promote destructive controversy. Controversy within a competitive context tends to promote closed-minded disinterest and rejection of the opponent’s ideas and information (Tjosvold, 1998). Within a cooperative context, constructive controversy induces feelings of comfort, pleasure, and helpfulness in discussing opposing positions; an open-minded listening to the opposing positions; motivation to hear more about the opponent’s arguments; more accurate understanding of the opponent’s position; and the reaching of more integrated positions where both one’s own and one’s opponent’s conclusions and reasoning are synthesized into a final position.

Skilled Disagreement.

For controversies to be managed constructively, participants need both cooperative and conflict management skills (Johnson, 2014; Johnson and F. Johnson, 2013). The following skills are necessary for following and internalizing these norms:

- I am critical of ideas, not people. I challenge and refute the ideas of the other participants, while confirming their competence and value as individuals. I do not indicate that I personally reject them.

- I separate my personal worth from criticism of my ideas.

- I remember that we are all in this together, sink or swim. I focus on coming to the best decision possible, not on winning.

- I encourage everyone to participate and to master all the relevant information.

- I listen to everyone’s ideas, even if I don’t agree.

- I restate what someone has said if it is not clear.

- I differentiate before I try to integrate. I first bring out all ideas and facts supporting both sides and clarify how the positions differ. Then I try to identify points of agreement and put them together in a way that makes sense.

- I try to understand both sides of the issue. I try to see the issue from the opposing perspective in order to understand the opposing position.

- I change my mind when the evidence clearly indicates that I should do so.

- I emphasize rationality in seeking the best possible answer, given the available data.

- I follow the golden rule of conflict: act toward opponents as you would have them act toward you. I want the opposing pair to listen to me, so I listen to them. I want the opposing pair to include my ideas in their thinking, so I include their ideas in my thinking. I want the opposing pair to see the issue from my perspective, so I take their perspective.

One of the most important skills is to be able to disagree with each other’s ideas while confirming each other’s personal competence (Tjosvold, 1998). Disagreeing with others while simultaneously confirming their personal competence results in being better liked. In addition, opponents tend to be less critical of your ideas, more interested in learning more about your ideas, and more willing to incorporate your information and reasoning into their own analysis of the problem. Disagreeing with others, and at the same time imputing that others are incompetent, tends to increase their commitment to their own ideas and their rejection of the other person’s information and reasoning. Protagonists are more likely to believe their goals are cooperative, integrate their perspectives, and reach agreement.

Another important set of skills for exchanging information and opinions within a constructive controversy is perspective taking (Johnson, 1971; Johnson and Johnson, 1989). More information, both personal and impersonal, is disclosed when one is interacting with a person who is engaging in perspective-taking behaviors such as paraphrasing, which communicates a desire to understand accurately. Perspective-taking ability increases one’s capacity to phrase messages so that they are easily understood by others and comprehend accurately the messages of others. Engaging in perspective taking in conflicts results in increased understanding and retention of the opponent’s information and perspective. Perspective taking facilitates the achievement of creative, high-quality problem solving. Finally, perspective taking promotes more positive perceptions of the information exchange process, of fellow group members, and of the group’s work.

A third set of skills involves the cycle of differentiation of positions and their integration (Johnson and F. Johnson, 2013). Group members should ensure that there are several cycles of differentiation (bringing out differences in positions) and integration (combining several positions into one new, creative position). The potential for integration is never greater than the adequacy of the differentiation already achieved. Most controversies go through a series of differentiations and integrations before reaching a final decision.

Rational Argument.

During a constructive controversy, group members have to follow the canons of rational argumentation (Johnson and Johnson, 2007): generating ideas, collecting relevant information, organizing it using inductive and deductive logic, and making tentative conclusions based on current understanding. Rational argumentation requires that participants keep an open mind, changing their conclusions and positions when others are persuasive and convincing in their presentation of rationale, proof, and logical reasoning.

STRUCTURING CONSTRUCTIVE CONTROVERSIES

Conflict is the gadfly of thought. It stirs us to observation and memory. It instigates invention. It shocks us out of sheeplike passivity, and sets us at noting and contriving . . . Conflict is a “sine qua non” of reflection and ingenuity.

—John Dewey, Human Nature and Conduct: Morals Are Human

Over the past thirty-five years, in addition to developing a theory of constructive controversy and validating it through a program of research, we have trained teachers, professors, administrators, managers, and executives in numerous countries to field-test and implement the constructive controversy procedure and developed a series of curriculum units, academic lessons, and training exercises structured for controversies. There are two formats, one for academic learning and one for decision-making situations. (A more detailed description of conducting constructive controversies may be found in Johnson and R. Johnson, 2007, and Johnson and F. Johnson, 2013.)

Constructive Controversy in the Classroom

In an English class, participants are considering the issue of civil disobedience. They learn that in the civil rights movement, individuals broke the law to gain equal rights for minorities. In numerous literary works, such as Huckleberry Finn , individuals wrestle with the issue of breaking the law to redress a social injustice. Huck wrestles with the issue of breaking the law in order to help Jim, the runaway slave.

In order to study the role of civil disobedience in a democracy, participants are placed in a cooperative learning group of four members. The group is given the assignment of reaching their best reasoned judgment about the issue and then divides into two pairs. One pair is given the assignment of making the best case possible for the constructiveness of civil disobedience in a democracy. The other pair is given the assignment of making the best case possible for the destructiveness of civil disobedience in a democracy. In the resulting conflict, participants draw from such sources as the Declaration of Independence by Thomas Jefferson; Civil Disobedience by Henry David Thoreau; “Speech at Cooper Union,” New York, by Abraham Lincoln; and “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King Jr. to challenge each other’s reasoning and analyses concerning when civil disobedience is, or is not, constructive.

Structure the Task.

The task must be structured cooperatively so that there are at least two well-documented positions (pro and con). The choice of topic depends on the interests of the instructor and the purposes of the course. In math courses, controversies may focus on different ways to solve a problem. In science classes, controversies may focus on environmental issues. Since drama is based on conflict, almost any piece of literature may be turned into a constructive controversy, for example, having participants argue over who is the greatest romantic poet. Since most history is based on conflicts, controversies can be created over any historical event. In any subject area, controversies can be created to promote academic learning and creative group problem solving.

Make Preinstructional Decisions and Preparations.

The teacher decides on the objectives for the lesson. Students are typically randomly assigned to groups of four, and each group is divided into two pairs. The pairs are randomly assigned to represent the pro or con position. The instructional materials are prepared so that group members know what position they have been assigned and where they can find supporting information. The materials helpful for each position are a clear description of the group’s task, a description of the phases of the constructive controversy procedure and the relevant social skills, a definition of the positions to be advocated with a summary of the key arguments supporting each position, and relevant resource materials, including a bibliography.

Explain and Orchestrate the Task, Cooperative Structure, and Constructive Controversy Procedure.

The teacher explains the task so that participants are clear about the assignment and understand the objectives of the lesson. Teachers may wish to help students get in role by presenting the issue to be decided in an interesting and dramatic way. Teachers structure positive interdependence by assigning two group goals. Students are required to

- Produce a group report detailing the nature of the group’s decision and its rationale. Members are to arrive at a consensus and ensure everyone participates in writing a high-quality group report. Groups present their report to the entire class.

- Individually take a test on both positions. Group members must master all the information relevant to both sides of the issue.

To supplement the effects of positive goal interdependence, the materials are divided among group members (resource interdependence), and bonus points may be given if all group members score above a preset criterion on the test (reward interdependence).

Academic Controversy Procedure.

The purpose of the constructive controversy is to maximize each student’s learning. Teachers structure individual accountability by ensuring that each student participates in each step of the constructive controversy procedure by individually testing each student on both sides of the issue and randomly selecting students to present their group’s report. Teachers specify the social skills participants are to master and demonstrate during the constructive controversy. The social skills emphasized are those involved in systematically advocating an intellectual position and evaluating and criticizing the position advocated by others, as well as the skills involved in synthesis and consensual decision making. Finally, teachers structure intergroup cooperation. When preparing their positions, for example, students can confer with classmates in other groups who are also preparing the same position.

The students’ overall goals are to learn all information relevant to the issue being studied and ensure that all other group members learn the information, so that their group can write the best report possible on the issue and all group members achieve high scores on the test of academic learning. The constructive controversy procedure is as follows (Johnson and R. Johnson, 2007):

-

Research, learn, and prepare a position

. In the group of four, one pair is assigned the pro position and the other pair the con position. Each pair is to prepare the best case possible for its assigned position by

- Researching the assigned position and learning all relevant information. Students are to read the supporting materials and find new information to support their position. The opposing pair is given any information students find that supports its position.

- Organizing the information into a persuasive argument that contains a thesis statement or claim (“George Washington was a more effective President than Abraham Lincoln”), the rationale supporting the thesis (“He accomplished a, b, and c”), and a logical conclusion that is the same as the thesis (“Therefore, George Washington was a more effective president than Abraham Lincoln”).

- Planning how to advocate the assigned position effectively to ensure it receives a fair and complete hearing. Make sure both pair members are ready to present the assigned position so persuasively that the opposing participants will understand and learn the information and, of course, agree that the position is valid and correct.

- Present and advocate the position . Students present the best case for their assigned position to ensure it gets a fair and complete hearing. They need to be forceful, persuasive, and convincing in doing so. Ideally, they will use more than one medium to increase the impact of the presentation. Students are to listen carefully to and learn the opposing position, taking notes and clarifying anything they do not understand.

- Engage in an open discussion in which there is spirited disagreement . Students discuss the issue by freely exchanging information and ideas. Students are to argue forcefully and persuasively for their position (presenting as many facts as they can to support their point of view); critically analyze the evidence and reasoning supporting the opposing position; ask for data to support assertions; refute the opposing position by pointing out the inadequacies in the information and reasoning; and rebut attacks on their position and present counterarguments. Students are to take careful notes on and thoroughly learn the opposing position. Students are to give the other position a trial by fire while following the norms for constructive controversy. Sometimes a time-out period will be provided so students can caucus with their partners and prepare new arguments. The teacher may encourage more spirited arguing, take sides when a pair is in trouble, play devil’s advocate, ask one group to observe another group engaging in a spirited argument, and generally stir up the discussion.

- Reverse perspectives . Students reverse perspectives and present the best case for the opposing position. Teachers may wish to have students change chairs. In presenting the opposing position sincerely and forcefully (as if it was their own), students may use their notes and add any new facts they know of. Students should strive to see the issue from both perspectives simultaneously.

-

Synthesize

. Students are to drop all advocacy and find a synthesis on which all members can agree. They summarize the best evidence and reasoning from both sides and integrate it into a joint position that is new and unique. Students are to

- Write a group report on the group’s synthesis with the supporting evidence and rationale. All group members sign the report indicating that they agree with it, can explain its content, and consider it ready to be evaluated. Each member must be able to present the report to the entire class.

- Take a test on both positions. If all members score above the preset criteria of excellence, each receives five bonus points.

- Process how well the group functioned and how its performance may be improved during the next constructive controversy. The specific conflict management skills required for constructive controversy may be highlighted.

- Celebrate the group’s success and the hard work of each member to make every step of the constructive controversy procedure effective.

Monitor the Controversy Groups and Intervene When Needed.

While the groups engage in the constructive controversy procedure, teachers monitor the learning groups and intervene to improve students’ skills in engaging in each step of the constructive controversy procedure and use the social skills appropriately. Teachers may also wish to intervene to highlight or reinforce particularly effective and skillful behaviors.

Evaluate Students’ Learning and Process Group Effectiveness.

At the end of each instructional unit, teachers evaluate students’ learning and give feedback. Qualitative as well as quantitative aspects of performance may be addressed. Students are graded on both the quality of their final report and their performance on the test covering both sides of the issue. The learning groups also process how well they functioned. Students describe what member actions were helpful (and unhelpful) in completing each step of the constructive controversy procedure and make decisions about what behaviors to continue or change. In whole-class processing, the teacher gives the class feedback and has participants share incidents that occurred in their groups.

Decision Making

A large pharmaceutical company faced the decision of whether to buy or build a chemical plant (Wall Street Journal , October 22, 1975). To maximize the likelihood that the best decision would be made, the president established two advocacy teams to ensure that both the buy and the build alternatives received a fair and complete hearing. An advocacy team is a subgroup that prepares and presents a particular policy alternative to the decision-making group. The buy team was instructed to prepare and present the best case for purchasing a chemical plant, and the build team was told to prepare and present the best case for constructing a new chemical plant near the company’s national headquarters.

The buy team identified over one hundred existing plants that would meet the company’s needs, narrowed the field down to twenty, further narrowed the field down to three, and then selected one plant as the ideal plant to buy. The build team contacted dozens of engineering firms and, after four months of consideration, selected a design for the ideal plant to build. Nine months after they were established, the two teams, armed with all the details about cost, presented their best case and challenged each other’s information, reasoning, and conclusions. From the spirited discussion, it became apparent that the two options would cost about the same amount of money. The group therefore chose the build option because it allowed the plant to be conveniently located near company headquarters. This procedure represents the structured use of constructive controversy to ensure high-quality decision making.

The purpose of group decision making is to decide on well-considered, well-understood, realistic action toward goals every member wishes to achieve. A group decision implies that some agreement prevails among group members as to which of several courses of action is most desirable for achieving the group’s goals. Making a decision is just one step in the more general problem-solving process of goal-directed groups, but it is a crucial one. After defining a problem or issue, thinking over alternative courses of action, and weighing the advantages and disadvantages of each, a group will decide which course is the most desirable to implement. To ensure high-quality decision making, each alternative course of action must receive a complete and fair hearing and be critically analyzed to reveal its strengths and weaknesses. In order to do so, the following constructive controversy procedure may be implemented. Group members

- Propose several courses of action that will solve the problem under consideration . When the group is making a decision, identify a number of alternative courses of action for the group to follow.

- Form advocacy teams . To ensure that each course of action receives a fair and complete hearing, assign two group members to be an advocacy team to present the best case possible for the assigned position. Positive interdependence is structured by highlighting the cooperative goal of making the best decision possible (goal interdependence) and noting that a high-quality decision cannot be made without considering the information that is being organized by the other advocacy teams (resource interdependence). Individual accountability is structured by ensuring that each member participates in preparing and presenting the assigned position. Any information discovered that supports the other alternatives is given to the appropriate advocacy pair.

-

Engage in the constructive controversy procedure

.

- Each advocacy team researches its position and prepares a persuasive presentation to convince other group members of its validity. The advocacy teams are given the time to research their assigned alternative course of action and find all the supporting evidence available. They organize what is known into a coherent and reasoned position. They plan how to present their case so that all members of the group understand thoroughly the advocacy pair’s position, give it a fair and complete hearing, and are convinced of its soundness.

- Each advocacy team presents without interruption the best case possible for their assigned alternative course of action to the entire group. Other advocacy teams listen carefully, taking notes and striving to learn the information provided.

- There is an open discussion characterized by advocacy, refutation, and rebuttal. The advocacy teams give opposing positions a trial by fire by seeking to refute them by challenging the validity of their information and logic. They defend their own position while continuing to attempt to persuade other group members of its validity. For higher-level reasoning and critical thinking to occur, it is necessary to probe and push each other’s conclusions. Members ask for data to support each other’s statements, clarify rationales, and show why their position is the most rational one. Group members refute the claims being made by the opposing teams and rebut the attacks on their own position. They take careful notes on and thoroughly learn the opposing positions. Members follow the specific rules for constructive controversy. Sometimes a time-out period needs to be provided so that pairs can caucus and prepare new arguments. Members should encourage spirited arguing and playing devil’s advocate. Members are instructed: “Argue forcefully and persuasively for your position, presenting as many facts as you can to support your point of view. Listen critically to the opposing pair’s position, asking them for the facts that support their viewpoint, and then present counterarguments. Remember this is a complex issue, and you need to know all sides to make a good decision.”

- Advocacy teams reverse perspectives and positions by presenting one of the opposing positions as sincerely and forcefully as team members can. Members may be told, “Present an opposing position as if it were yours. Be as sincere and forceful as you can. Add any new facts you know. Elaborate their position by relating it to other information you have previously learned.” Advocacy pairs strive to see the issue from all perspectives simultaneously.

- All members drop their advocacy and reach a decision by consensus. They may wish to summarize their decision in a group report that details the course of action they have adopted and its supporting rationale. Often the chosen alternative represents a new perspective or synthesis that is more rational than the two assigned. All group members sign the report, indicating that they agree with the decision and will do their share of the work in implementing it. Members may be instructed: “Summarize and synthesize the best arguments for all points of view. Reach a decision by consensus. Change your mind only when the facts and the rationale clearly indicate that you should do so. Write a report with the supporting evidence and rationale for your synthesis that your group has agreed on. When you are certain the report is as good as you can make it, sign it.”

- Group members process how well the group functioned and how their performance may be improved during the next constructive controversy.

- Implement the decision . Once the decision is made, all members commit themselves to implement it regardless of whether they initially favored the alternative adopted.

Controversies are common within decision-making situations. In the mining industry, for example, engineers are accustomed to address issues such as land use, air and water pollution, and health and safety. The complexity of the design of production processes, the balancing of environmental and manufacturing interests, and numerous other factors often create the opportunity for constructive controversy. Most groups waste the benefits of such disputes, but every effective decision-making situation thrives on what constructive controversy has to offer. Decisions are by their very nature controversial, as alternative solutions are suggested and considered before agreement is reached. When a decision is made, the constructive controversy ends and participants commit themselves to a common course of action.

CONSTRUCTIVE CONTROVERSY AND DEMOCRACY

Thomas Jefferson believed that free and open discussion should serve as the basis of influence within society, not the social rank within which a person was born. Based on the beliefs of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and their fellow revolutionaries, American democracy was founded on the premise that truth will result from free and open-minded discussion in which opposing points of view are advocated and vigorously argued. Every citizen is given the opportunity to advocate for his or her ideas and to listen respectfully to opposing points of view.

Political discourse is the formal exchange of reasoned views as to which of several alternative courses of action should be taken to solve a societal problem (Johnson and Johnson, 2000). It is intended to involve all citizens in the making of the decision. Citizens are expected to persuade one another through valid information and logic as to what course of action would be most effective. Political discourse is aimed at making a decision in a way that ensures all citizens are committed to implement the decision (whether they agree with it or not) and the democratic process. Once a decision is made, the minority is expected to go along willingly with the majority because they know they have been given a fair and complete hearing. To be a citizen in our democracy, individuals need to internalize the norms for constructive controversy as well as mastering the process of researching an issue, organizing their conclusions, advocating their views, challenging opposing positions, making a decision, and committing themselves to implement the decision made (regardless of whether one initially favored the alternative adopted). In essence, the use of constructive controversy teaches the participants to be active citizens of a democracy.

CONCLUSION

Thomas Jefferson based his faith in the future of democracy on the power of constructive conflict. Based on structure-process-outcome theory (Watson and Johnson, 1972), it may be posited that the way in which conflict is structured determines how group members interact, which in turn determines the resulting outcomes. Conflicts may be structured to produce constructive controversy or concurrence seeking (as well as debate or individualistic problem solving). Each way of structuring conflict leads to a different process of interaction among group members and different outcomes.

The process of constructive controversy includes forming an initial conclusion when presented with a problem; being confronted by other people with different conclusions, becoming uncertain as to the correctness of one’s views, actively searching for more information and a more adequate perspective; and forming a new, reconceptualized, and reorganized conclusion. The process of concurrence seeking includes seeking a quick decision, avoiding any disagreement or dissent, emphasizing agreement among group members, and avoiding realistic appraisal of alternative ideas and courses of action.

Compared to concurrence seeking (and debate and individualistic efforts), controversies tend to result in greater achievement and retention, cognitive and moral reasoning, perspective taking, open-mindedness, creativity, task involvement, continuing motivation, attitude change, interpersonal attraction, and self-esteem. This is especially true when the situational context is cooperative, there is some heterogeneity among group members, information and expertise are distributed within the group, members have the necessary conflict skills, and the canons of rational argumentation are followed.

While the constructive controversy process can occur naturally, it may be consciously structured in decision making and learning situations. This involves dividing a cooperative group into two pairs and assigning them opposing positions. The pairs then develop their position, present it to the other pair and listen to the opposing position, engage in a discussion in which they attempt to refute the other side and rebut attacks on their position, reverse perspectives and present the other position, and drop all advocacy and seek a synthesis that takes both perspectives and positions into account. Engaging in the constructive controversy procedure skillfully provides an example of how conflict creates positive outcomes.

References

Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Janis, I. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Johnson, D. W. (1971). Role reversal: A summary and review of the research. International Journal of Group Tensions, 1 , 318–334.

Johnson, D. W. (2014). Reaching out: Interpersonal effectiveness and self-actualization (11th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Johnson D. W., & Johnson, F. (2013). Joining together: Group theory and group skills (11th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1979). Conflict in the classroom: Constructive controversy and learning. Review of Educational Research, 49 , 51–61.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1989). Cooperation and competition: Theory and research . Edina, MN: Interaction.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (2000). Civil political discourse in a democracy: The contribution of psychology. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 6 (4), 291–317.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (2003). Controversy and peace education. Journal of Research in Education, 13 (1), 71–91.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (2007). Creative controversy: Intellectual challenge in the classroom (4th ed.). Edina, MN: Interaction.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). Energizing learning: The instructional power of conflict. Educational Researcher, 38 (1), 37–52.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R., & Holubec, E. (2008). Cooperation in the classroom (8th ed.). Edina, MN: Interaction.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, F., & Johnson, R. (1976). Promoting constructive conflict in the classroom. Notre Dame Journal of Education, 7 , 163–168.

Lowry, N., & Johnson, D. W. (1981). Effects of controversy on epistemic curiosity, achievement, and attitudes. Journal of Social Psychology, 115 , 31–43.

Tjosvold, D. (1998). Cooperative and competitive goal approach to conflict: Accomplishments and challenges. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 47 (3), 285–342.

Watson, G., & Johnson, D. W. (1972). Social psychology: Issues and insights (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott.