CHAPTER FIVE

TRUST, TRUST DEVELOPMENT, AND TRUST REPAIR

a

Roy J. Lewicki

Edward C. Tomlinson

The relationship between conflict and trust is an obvious one. Most people think of trust as the glue that holds a relationship together. If individuals or groups trust each other, they can work through conflict relatively easily. If they do not trust each other, conflict often becomes destructive, and resolution is more difficult. Bitter conflict itself generates animosity and pain that is not easily forgotten; moreover, the parties no longer believe what the other says or believe that the other will follow through on commitments and proposed actions. Therefore, acrimonious conflict often serves to destroy trust and increase distrust, which makes conflict resolution ever more difficult and problematic.

In this chapter, we review some of the work on trust and show its relevance to effective conflict management. We also extend some of this work to a broader understanding of the key role of trust in relationships and how different types of relationships can be characterized according to the levels of trust and distrust that are present. Finally, we describe procedures for repairing trust that has been broken and for managing distrust in ways that can enhance short-term conflict containment while rebuilding trust over the long run.

WHAT IS TRUST?

Trust is a concept that has received attention in several social science literatures: psychology, sociology, political science, economics, anthropology, history, and sociobiology (for reviews, see Worchel, 1979; Gambetta, 1988; Lewicki and Bunker, 1995; Bachmann and Zaheer, 2006, 2008). As can be expected, each literature approaches the problem with its own disciplinary lens and filters. Until recently, there has been remarkably little effort to integrate these perspectives or articulate the key role that trust plays in critical social processes, such as cooperation, coordination, and performance (for notable exceptions, see Kramer and Tyler, 1996; Sitkin, Rousseau, Burt, and Camerer, 1998).

Worchel (1979) proposes that these differing perspectives on trust can be aggregated into at least three groups (see also Lewicki and Bunker, 1995, 1996, for detailed exploration of theories within each category):

- The views of personality theorists, who focus on individual personality differences in the readiness to trust and on the specific developmental and social contextual factors that shape this readiness. At this level, trust is conceptualized as a belief, expectancy, or feeling deeply rooted in the personality, with origins in the individual’s early psychosocial development (see Worchel, 1979; Rotter, 1971; Kramer, 2006).

- The views of sociologists and economists, who focus on trust as an institutional phenomenon. Institutional trust can be defined as the belief that future interactions will continue, based on explicit or implicit rules and norms (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, and Camerer, 1998; Currall and Inkpen, 2006). At this level, trust can be conceptualized as a phenomenon within and among institutions and as the trust individuals put in those institutions. For example, one group of researchers explored the role of trust in interfirm relationships at both the interpersonal and organizational levels. They showed that high levels of interorganizational trust enhanced supplier performance, lowered costs of negotiation, and reduced conflict between firms (Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone, 1998). Others argue that organizations must significantly redesign their governance mechanisms in order to address the considerable loss of public trust in American corporations in the past decade (Caldwell and Karri, 2005).

- The views of social psychologists, who focus on the interpersonal transactions between individuals that create or destroy trust at the interpersonal and group levels. At this level, trust can be defined as expectations of the other party in a transaction, considering the risks associated with assuming and acting on such expectations and contextual factors that either contribute to or inhibit development and maintenance of the relationship. The earliest examples of this perspective can be found in the pioneering studies of Deutsch (1958, 1960, 1962) and his exploration of the dynamics of trust among experimental subjects playing a prisoner’s dilemma game. Examples of elaborated models of trust, particularly in organizations, can be found in Jones and George, (1998), Dirks and Ferrin (2001), and Colquitt, Scott, and LePine (2007).

A DEFINITION OF TRUST

The literature on trust is rich with definitions and conceptualizations (see Bigley and Pearce, 1998). In this chapter, we adopt as the definition of trust “an individual’s belief in, and willingness to act on the basis of, the words, actions, and decisions of another” (McAllister, 1995, p. 25; Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies, 1998). Implicit in this definition, as in other comparable ones (Boon and Holmes, 1991), are three elements that contribute to the level of trust one has for another: the individual’s chronic disposition toward trust (see our earlier discussion of personality), situational parameters (some are suggested above, others below), and the history of their relationship. Our current focus is on the relationship dimension of trust, which we address throughout this chapter.

WHY TRUST IS CRITICAL TO RELATIONSHIPS

There are many types of relationship, and it can be assumed that the nature of trust and its development are not the same in all the types. In this chapter, we discuss two basic types: professional and personal relationships. The former is considered to be a task-oriented relationship in which the parties’ attention and activities are primarily directed toward achievement of goals external to their relationship. The latter is considered to be a social-emotional relationship whose primary focus is the relationship itself and the persons in the relationship (see Deutsch, 1985, for a complex treatment of types of interdependence in relationships; see also Sheppard and Sherman, 1998; and chapters 1 and 37 in this handbook).

An effort to describe professional relationship development in a business context was proposed by Shapiro, Sheppard, and Cheraskin (1992). They suggest that three types of trust operate in developing a business relationship: deterrence-based trust, knowledge-based trust, and identification-based trust. Expanding on this work, Lewicki and Bunker (1995, 1996) adopted these three types of trust and made several major additions and modifications. We briefly present these ideas (Lewicki and Bunker’s articles provide a richer and fuller description of each type of trust and how it is proposed that the types are linked together in a developmental sequence).

Calculus-Based Trust

Shapiro et al. (1992) identified the first type as deterrence-based trust . They argued that this form of trust is based in ensuring consistency of behavior; simply put, individuals do what they promise because they fear the consequences of not doing what they say. Like any other behavior based on a theory of deterrence, trust is sustained to the degree that the deterrent (punishment) is clear, possible, and likely to occur if the trust is violated. Thus, the threat of punishment is likely to be a more significant motivator than the promise of reward.

Lewicki and Bunker (1995, 1996) called this form calculus-based trust (CBT). We argue that trust at this stage is grounded not only in the fear of punishment for violating the trust but also in the rewards to be derived from preserving it. This kind of trust is an ongoing, market-oriented, economic calculation whose value is determined by the outcomes resulting from creating and sustaining the relationship relative to the costs of maintaining or severing it. Compliance with calculus-based trust is often ensured by both the rewards of being trusting (and trustworthy) and the threat that if trust is violated, one’s reputation can be hurt through the other person’s network of friends and associates. Even if you are not an honest person, having a reputation for honesty (or trustworthiness) is a valuable asset that most people want to maintain. So even if there are opportunities to be untrustworthy, any short-term gains from untrustworthy acts must be balanced, in a calculus-based way, against the long-term benefits from maintaining a good reputation.

The most appropriate metaphor for the growth of CBT is the children’s game Chutes and Ladders. Progress is made on the game board by throwing the dice and moving ahead (“up the ladder”) in a stepwise fashion. However, a player landing on a “chute” is quickly dropped back a large number of steps. Similarly, in calculus-based trust, forward progress is made by climbing the ladder, or building trust, slowly, step by step. People prove through simple actions that they are trustworthy, and, similarly, they are regularly testing others’ trust. Results of such incremental trust development are being reported in the neuroscience literature. In one study, researchers found that as parties played a game of economic reciprocity and one party gained a reputation for trustworthy choices, the other’s intention to make a reciprocal trusting choice and actual trust decision could be tracked through changes in brainwaves in the dorsal striatum (King-Casas et al., 2005). Balancing this trust-building development, trust declines can also occur frequently; a single event of inconsistency or unreliability may “chute” the relationship back several steps—or, in the worst case, back to square one. Thus, CBT is often quite partial and fragile.

The dynamics of this trust development may not always be as rational as this description suggests. In fact, trustors and those who are trusted may be motivated by different things. 1 Trustors are more likely to focus on the risk associated with taking the trusting action. Thus, trust-building activities such as placing trust in the other in spite of the possible associated risks may be both irrational and necessary to develop that trust. At the same time, the trusted are more likely to focus on the level of benefits they are receiving. Thus, trustors will be cautious; they focus on risk of trust and may be more likely to initiate trusting actions that do not risk extending high (but potentially unreciprocated) rewards to the other. In contrast, the trusted are more likely to focus on the benefits and may be more likely to reciprocate (and create joint gain for the parties) when the reward level is high (Malhotra, 2004; Weber, Malhotra, and Murnighan, 2005). Paradoxically, from the trustee’s point of view, trust cannot be asked for, but is more likely to be accepted if it is offered.

Identification-Based Trust

While CBT is usually the first stage in developing more intimate personal relationships, it often leads to a second type of trust, based on identification with the other’s desires and intentions. This type of trust exists because the parties can effectively understand and appreciate one another’s wants (Rousseau et al., 1998, have called this relationship-based trust). This mutual understanding is developed to the point that each person can effectively act for the other. Identification-based trust (IBT) thus permits a party to serve as the other’s agent and substitute for the other in interpersonal transactions (Deutsch, 1949). Both parties can be confident that their interests are fully protected and that no ongoing surveillance or monitoring of one another is necessary. A true affirmation of the strength of IBT between parties can be found when one party acts for the other even more zealously than the other might demonstrate, such as when a good friend dramatically defends you against a minor insult.

A corollary of this “acting for each other” in IBT is that as the parties come to know each other better and identify with the other, they also understand more clearly what they must do to sustain the other’s trust. 2 This process might be described as second-order learning. One comes to learn what really matters to the other and comes to place the same importance on those behaviors as the other does. Certain types of activities strengthen IBT (Shapiro et al., 1992; Lewicki and Bunker, 1995, 1996; Lewicki and Stevenson, 1998), such as developing a collective identity (a joint name, title, or logo), co-location in the same building or neighborhood, creating joint products or goals (a new product line or a new set of objectives), or committing to commonly shared values (such that the parties are committed to the same objectives and so can substitute for each other in external transactions). For example, at the leadership level, De Cremer and van Knippenberg (2005) have shown that leader self-sacrifice enhanced follower trust, cooperation, and collective identification with the leader. At the team level, Han and Harms (2010) have shown that identification with the team strengthened trust and decreased both task and relationship conflict. Finally, at the organization level, Kramer (2001) has argued that identification with the organization’s goals leads individuals to trust the organization and share a presumptive trust of others within it.

Thus IBT develops as one both knows and predicts the other’s needs, choices, and preferences and as one also shares some of those same needs, choices, and preferences as one’s own. Increased identification enables us to think like the other, feel like the other, and respond like the other. A collective identity develops; we empathize strongly with the other and incorporate parts of their psyche into our own identity (needs, preferences, thoughts, and behavior patterns). This form of trust can develop in working relationships if the parties come to know each other very well, but it is most likely to occur in intimate, personal relationships. Moreover, this form of trust stabilizes relationships during periods of conflict and negativity. Thus, when high-trusting parties engage in conflict, they tend to see the best in their partner’s motives because they make different attributions about the conflict compared to low-trusting parties. Thus, the determinant of whether relationships maintain or dissolve in a conflict may be due to the attributions parties make about the other’s motives, determined by the existing level of trust (Miller and Rempel, 2004).

Music suggests a suitable metaphor for IBT: the harmonizing of a barbershop quartet. The parties learn to sing in a harmony that is integrated and complex. Each knows the others’ vocal range and pitch; each singer knows when to lead and follow; and each knows how to work with the others to maximize their strengths, compensate for their weaknesses, and create a joint product that is much greater than the sum of its parts. The unverbalized, synchronous chemistry of a cappella choirs, string quartets, cohesive work groups, emergency medical delivery teams, and championship basketball teams are excellent examples of this kind of trust in action.

Trust and Relationships: An Elaboration of Our Views

In addition to our views of these two forms of trust, we need to introduce two ideas about trust and relationships. The first is that trust and distrust are not simply opposite ends of the same dimension but conceptually different and separate. Second, relationships develop over time, and the nature of trust changes as they develop.

Trust and Distrust Are Fundamentally Different.

In addition to identifying types of trust, Lewicki et al. (1998) have argued that trust and distrust are fundamentally different from each other rather than merely more or less of the same thing (see also Ullman-Margalit, 2004; Kramer and Cook, 2004). Although trust can be defined as “confident positive expectations regarding another’s conduct,” distrust can indeed be “confident negative expectations” regarding another’s conduct (Lewicki et al., 1998). Thus, just as trust implies belief in the other, a tendency to attribute virtuous intentions to the other and willingness to act on the basis of the other’s conduct, distrust implies fear of the other, a tendency to attribute sinister intentions to the other, and a desire to protect oneself from the effects of another’s conduct.

Relationships Are Developmental and Multifaceted.

In discussing our views of the types of trust, we also pointed out that these forms of trust develop in different types of relationships. Work (task) relationships tend to be characterized by CBT but may develop some IBT. Intimate (personal) relationships tend to be characterized by IBT but may require a modicum of CBT for the parties to work together effectively or coordinate their lives together (e.g., share property, meet obligations and commitments).

All relationships develop as parties share experiences with each other and gain knowledge about the other. Every time we encounter another person, we gain a new experience that strengthens or weakens the relationship. If our experiences with another person are all within the same limited context (I know the server at the bakery because I buy my bagel and juice there every morning), then we gain little additional knowledge about the other (over time, I have a rich but very narrow range of experience with that server). However, if we encounter the other in different contexts (if I join a colleague to talk research, coteach classes, and play tennis), then this variety of shared experience is likely to develop into broader, deeper knowledge of the other.

People come to know each other in many contexts and situations. Conversely, they may trust others in some contexts and distrust in others. You may have friends you would trust to take care of your child but not to pay back money that you loan them. A relationship is made up of components of experience that one individual has with another. Within these relationships, some elements hold varying degrees of trust, while others hold varying degrees of distrust. Our overall evaluation of the other person involves some complex judgment that weighs the scope of the relationship and elements of trust and distrust. Most people are able to be quite specific in describing both the trust and distrust elements in their relationship. If the parties teach a class together, work together on a committee, play tennis together, and belong to the same church, the scope of their experience is much broader than for parties who simply work together on a committee.

Finally, we cannot assume that we begin with a blank slate of trust or distrust in relationships. In fact, we seldom approach others with no information. Rather, we tend to approach the other with some initial level of trust or of caution (McKnight, Cummings, and Chervaney, 1998). In fact, some authors have argued that there is a strong disposition to overtrust in early relationships, a situation where the trustor’s trust exceeds the level that might be warranted by situational circumstances (Goel, Bell, and Pierce, 2005). Thus, determining the appropriate level of initial trust prior to substantial data about the other party may be more difficult than determining the appropriate level after some data have been collected (Ullman-Margalit, 2004).

In addition, we develop expectations about the degree to which we can trust new others, depending on a number of factors:

- Personality predispositions . Research has shown that individuals differ in their predisposition to trust another (Rotter, 1971; Wrightsman, 1994). The higher an individual ranks in predisposition to trust, the more she expects trustworthy actions from the other, independent of her own actions. Similarly, research has shown that individuals differ in their predispositions to be cynical or show distrust (Kanter and Mirvis, 1989).

- Psychological orientation . Deutsch (1985) has characterized relationships in terms of their psychological orientations, or the complex synergy of “interrelated cognitive, motivational and moral orientations” (p. 94). He maintains that people establish and maintain social relationships partly on the basis of these orientations, such that orientations are influenced by relationships and vice versa. To the extent that people strive to keep their orientations internally consistent, they may seek out relationships that are congruent with their own psyche.

- Reputations and stereotypes . Even if we have no direct experience with another person, our expectations may be shaped by what we learn about him or her through friends, associates, and hearsay (Ferris, Blass, Douglas, Kolodinsky, and Treadway, 2003). The other’s reputation often creates strong expectations that lead us to look for elements of trust or distrust and also to approach the relationship attuned to trust or to suspicion (Glick and Croson, 2001).

- Experience over time . With most people, we develop facets of experience as we talk, work, coordinate, and communicate. Some of these facets are strong in trust, while others may be strong in distrust. For example, one study of organizational communication showed that as frequency of communication increases, the parties’ general predisposition toward the other party decreased in importance, while organizational and situational factors (e.g., tenure, autonomy) increased in importance in the determination of trust. Over time, it is likely that either trust or distrust context or experience elements begin to dominate the experience base, leading to a stable and easily defined relationship. As these patterns stabilize, we tend to generalize across the scope of the relationship and describe it as one of high or low trust or distrust.

Implications of This Revised View of Trust.

By incorporating the revisions just described into existing models of trust, we can summarize our ideas about trust and distrust within relationships:

- Relationships are multifaceted, and each facet represents an interaction that provides us with information about the other. The greater the variety of settings and contexts in which the parties interact, the more complex and multifaceted the relationship becomes.

- Within the same relationship, elements of trust and distrust may peacefully coexist because they are related to different experiences with the other or knowledge of the other in varied contexts.

- Relationships balanced with trust and distrust are likely to be healthier than relationships grounded only in trust. Particularly in organizational and managerial relationships, “neither complete lack of trust, nor total trust, nor very high levels of affective attachment, nor enduring social reliance, nor destructive mistrust and betrayal, are appropriate or positive for organizational purposes” (Atkinson and Butcher, 2003, p. 297). Particularly in business relationships, unquestioning trust without distrust is more likely to create more problems than solutions (Wicks, Berman, and Jones, 1999; Blois, 2003). Similarly, unquestioning distrust (e.g., paranoia) can sometimes be healthy, but sometimes perverse (Kramer, 2001, 2002). To quote the popular caution: “Trust . . . but verify!”

- Facets of trust or distrust are likely to be calculus based or identification based. Earlier, we defined trust as confident positive expectations regarding another’s conduct and distrust as

confident negative expectations regarding another’s conduct. We now elaborate on those definitions:

Calculus-based trust (CBT) is a confident positive expectation regarding another’s conduct. It is grounded in impersonal transactions, and the overall anticipated benefits to be derived from the relationship are assumed to outweigh any anticipated costs.

Calculus-based distrust (CBD) is a confident negative expectation regarding another’s conduct. It is also grounded in impersonal transactions, and the overall anticipated costs to be derived from the relationship are assumed to outweigh the anticipated benefits.

Identification-based trust (IBT) is a confident positive expectation regarding another’s conduct. It is grounded in perceived compatibility of values, common goals, and positive emotional attachment to the other.

Identification-based distrust (IBD) is a confident negative expectation regarding another’s conduct, grounded in perceived incompatibility of values, dissimilar goals, and negative emotional attachment to the other.

Characterizing Relationships Based on Trust Elements

Because there can be elements of each type of trust and distrust in a relationship, there are many types of relationships, varying in the combination of elements of calculus-based trust, calculus-based distrust, identification-based trust, and identification-based distrust. All of these types of relationships theoretically exist, but given the relative infancy of this theory, we cannot effectively explore or discuss all of the possibilities.

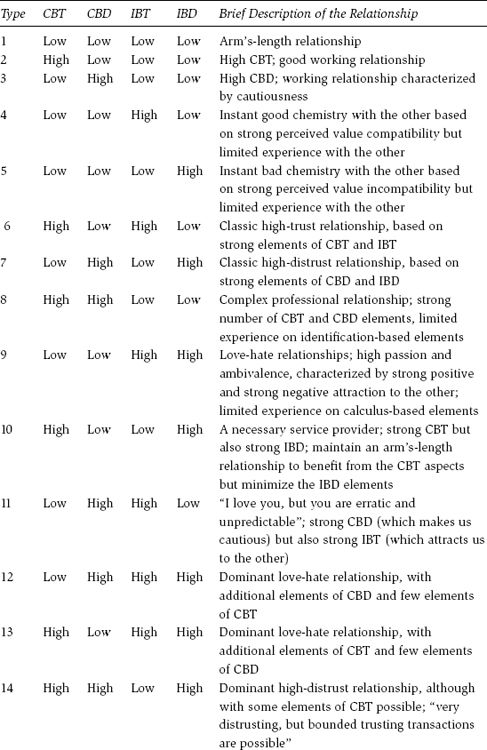

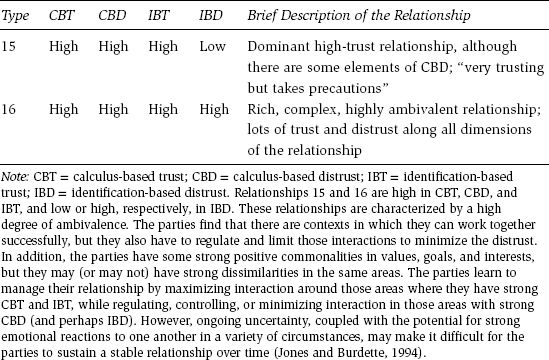

To simplify this framework, let us assume that we can characterize relationships as simply high or low in the number of CBT, CBD, IBT, and IBD elements. This reduces the framework to sixteen possible combinations of trust elements (see table 5.1 ). Each row in this table represents a type of relationship based on the pattern of high or low levels of CBT, CBD, IBT, and IBD. These combinations are listed in the first four columns, and a brief description of the relationship is found in the last column.

Table 5.1 Sixteen Relationship Types Based on Dominant Trust and Distrust Elements

Based on our model, all sixteen types of relationship are hypothetically possible and may be found among one’s friends, acquaintances, and professional associates. However, space limitations in this chapter only permit us to offer a few selective illustrations.

Relationship 1 of table 5.1 , low in all forms of trust and distrust, represents new relationships in which the actors have little prior information and no expectations about each other. Type 1 relationships may also not be new to us, but because we have had such limited interaction with the other, there has been no basis for developing significant trust or distrust. Nevertheless, we tend to extend a modicum of trust. We walk into a new dry cleaning store chosen at random and give the attendant our favorite suit because we trust that the dry cleaner will clean it, not ruin it. The very existence of the shop’s appearance as a clean, professional-looking, legitimate business is sufficient to satisfy our trust. Thus, while the “low-low-low-low” situation may exist hypothetically, in fact this type of relationship may occur only when there are actual data for the trustor to infer that low levels of trust and distrust are the most appropriate disposition (Jeffries and Reed, 2000).

Relationship 2 is high only in CBT. This is likely to be a business or professional relationship in which the actors have had a number of successful exchanges and transactions that are beneficial to them. Over time, each person’s behavior has been positive and consistent, and the parties rely on each other to continue to act in the same way. For example, my investment counselor has made very good decisions about my money over time, and I continue to take his advice about when it is time to buy or sell.

Relationship 6, high in CBT and IBT, represents a prototypical high-trust relationship. Both parties benefit greatly from the relationship, so they seek out opportunities to be together and do things together. Continued success in these interactions enhances their trust.

MANAGING TRUST AND DISTRUST IN CONFLICT SITUATIONS

As we have noted, trust and distrust develop as people gain knowledge of one another. One of the benefits of our model of relationships based on trust is its clear explanation of changes in relationships over time. Relationship changes can be mapped by identifying actions that change the balance of the trust and distrust elements in the relationship or fundamentally alter the type of interaction in the relationship. In this section, we identify behaviors that previous research suggests can change perceptions of trust and distrust.

Actions That Build Calculus-Based Trust

People who are involved in relationships with high levels of CBT and low levels of IBT (such as relationship 2 in table 5.1 ) may have relatively stable expectations about these relationships. Initially CBT may be based on only the other’s reputation for trustworthiness (Gabarro, 1978; Butler, 1991). Over time, CBT develops as we observe the other and identify certain behavior patterns over time. Previous research has demonstrated that effective business relationships are based on predictability (Jennings, 1971), reliability (McAllister, 1995), and consistency of behavior (Gabarro, 1978). In work relationships, then, CBT is enhanced if people behave the same appropriate way consistently (at different times and in different situations), meet stated deadlines, and perform tasks and follow through with planned activities as promised.

In any context, if people act consistently and reliably, we are likely to see them as credible and trustworthy (Lewicki and Stevenson, 1998). For example, students often want to be able to trust their faculty instructors. To the degree that faculty clearly announce their course requirements and grading criteria, use those standards consistently, follow the course outline clearly, and keep their promises, they enjoy a great deal of trust from students.

Emotions can also build trust. Happiness and gratitude can build trust, while anger decreases it. The salience of the emotion’s cause and familiarity with the target moderate the relationship between emotions and trust (Dunn and Schweitzer, 2005).

Strategies to Manage Calculus-Based Distrust

As we have noted, CBT and CBD are often founded on a cost-benefit analysis. If the costs of depending on someone’s behavior outweigh the benefits, we are typically inclined to change or terminate the relationship. This may be feasible with personal friendships, but it is often not possible to leave professional relationships even when CBD is high. 3 Consequently, it is necessary to manage CBD so that the parties can continue to work together.

There are several strategies for managing CBD:

- Agree explicitly on expectations as to what is to be done, on deadlines for completion, and on the penalties for failing to comply with them. This upfront commitment by the parties to a course of action and to the consequences for nonperformance sets explicit expectations for behavior that may reduce the fear parties have about the vulnerabilities associated with working together.

- Agree on procedures for monitoring and verifying the other’s actions. If we distrust someone, we seek ways to monitor what he does to ensure that future trust violations do not occur. Writing about disarmament during the Cold War, Osgood (1962) explicitly proposed unilateral steps that antagonistic parties can take to signal good faith and an intention to build trustworthiness.

- Cultivate alternative ways to have one’s needs met. Someone who distrusts another (and the other’s possible performance in the future) tries to find ways to minimize future interaction or discover alternative ways to get needs met. Distrust can be managed by letting the other know that one has an alternative and is willing to invoke it if there are further trust violations.

- Increase the other’s awareness of how his own performance is perceived by others. Workplace difficulties are sometimes alleviated when supervisors discuss performance expectations with subordinates rather than assuming that both have the same understanding of what constitutes appropriate work behavior. Many workplace diversity efforts are actually attempts to familiarize workers from different cultures with one another. Behaviors that seemed strange or inconsistent may be explained as differences in cultural patterns of interaction. Once the parties recognize the logic inherent in each other’s behavior, they are likely to view the other as consistent and predictable (Foeman, 1991), which enhances CBT.

Actions That Build IBT

Research indicates that trust is enhanced if the parties spend time together-sharing personal values, perceptions, motives, and goals (Gabarro, 1978). But specific time must be set aside for engaging in this activity. Parties in work relationships may do this in the course of working together, while parties in personal relationships explicitly devote time to these activities. In general, parties should engage in processes that permit them to share:

- Common group membership (Brewer and Kramer, 1986)

- Common interests

- Common goals and objectives

- Similar reactions to common situations

- Situations where they stand for the same values and principles, thereby demonstrating integrity (Lewicki and Stevenson, 1998)

For example, Kramer (2001), interpreting a stream of research on the impact of common group membership on identity and trust, argues that common group and organizational membership was sufficient to solidify trust, and in a way that went significantly beyond the ability of simple reputation or calculative-based considerations for trust development. Common group membership creates actions that also have expressive and symbolic meanings: “engaging in acts of trust thus provides organizational members with an opportunity to communicate to others the symbolic value they attach to their organizational identity. From this perspective, the psychological significance of trust acts resides . . . in the social motives and affiliative needs of group members that are met through such actions” (Kramer, 2001, p. 171).

Similarly, Rothman (1997) has proposed a four-step framework for resolving identity-based disputes. The second key step in the framework is resonance, or the process of reflexive reframing, by which parties discover common values, concerns, interests, and needs. In Rothman’s framework, effective completion of the resonance step permits individuals to establish a basis of commonality (IBT) on which to build mutually acceptable solutions to managing their dispute. Moreover, studies in organizations have indicated that one component of managers’ trust in their subordinates is the degree to which the employee demonstrates that she has the best interests of the manager or the organization (or both) at heart (Schoorman, Mayer, and Davis, 1996; Butler, 1995). If we believe that the other shares our concerns and goals, IBT is enhanced. IBT may also be increased if we observe the other reacting as we believe we would react in another context (Lewicki and Stevenson, 1998); however, research on the connection between similarity and perceptions of trustworthiness has produced mixed results (see Huston and Levinger, 1978).

It should be noted that IBT has a strong emotional component and is probably largely affective in nature (Lewicki and Bunker, 1995, 1996; McAllister, 1995). Despite our attempt to think logically about our relationships, how we respond to others often depends on our idiosyncratic, personal reactions to aspects of the other’s physical self-presentation (Chaiken, 1986), the situation and circumstances under which we meet the person (Jones and Brehm, 1976), or even our mood at the time of the encounter. Consequently, we are likely to build IBT only with others whom we feel legitimately share our goals, interests, perceptions, and values and if we meet under circumstances that facilitate our learning of that similarity.

Strategies to Manage IBD

If we believe that another’s values, perceptions, and behaviors are damaging to our own, we often find it difficult to maintain even a semblance of a working relationship. However, if we anticipate that we will have a long-term relationship with someone who invokes elements of IBD and believe we have limited alternatives, there are strategies for managing the encounter that offer both opportunities for self-protection and attainment of mutual goals. One of the most important strategies is to develop sufficient CBT so that the parties can be comfortable with the straightforward behavioral expectations that each has for the relationship.

As we noted in the section on managing CBD, explicitly specifying and negotiating expected behaviors may be necessary to provide both parties with a comfort zone sufficient to sustain their interaction. It may also be helpful for the actors to openly acknowledge the areas of their mutual distrust. By doing so, they can explicitly talk about areas where they distrust each other and establish safeguards that anticipate distrustful behaviors and afford protection against potential consequences (Lewicki and Stevenson, 1998). For example, if the parties have strong disagreements about certain value-based issues (religious beliefs, political beliefs, personal values), they may be able to design ways to keep these issues from interfering with their ability to work together in more calculus-based transactions. If the costs and benefits of consistent action are clear to both parties, the groundwork for CBT may be established. This enables them to interact in future encounters with some confidence that despite deep-seated differences, they will not be fundamentally disadvantaged or harmed in the relationship.

We should note here that our working assumption is that the trustor’s strong IBD is healthy and appropriate—that is, grounded in accurate perceptions and judgments of the identity differences between the parties. Kramer (2001, 2002) has also written extensively about the conditions under which paranoid cognitions develop and the conditions under which this paranoia may be prudent or highly destructive to the actor and to relationships.

What Happens If Trust Is Violated?

Trust violations occur if we experience an outcome that does not conform to our expectations of behavior for the trustee, and this outcome is attributed to the trustee as opposed to the situation or some other person (Tomlinson and Mayer, 2009). Note that trust violations can occur in both directions—that is, we can expect trusting behavior and encounter distrust, or we can expect distrusting behavior and encounter trust. 4 Our discussion here elaborates on the more commonly studied case of expecting trust and encountering distrust. If this disconfirming information is significant enough or if it begins to occur regularly in ongoing encounters, we are likely to reduce our perceptions of trust dramatically and possibly alter the type of relationship we have with the other (Lewicki and Bunker, 1996). 5

Research on the consequences of trust violations consistently shows that violations lead to a reduction in subsequent trust and cooperation (Deutsch, 1958; 1973; Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Kramer, 1996). For example, employees’ trust in their employer declines when they perceive that their employer has violated the psychological contract—that is, the expectations held by both parties about the nature of the employment relationship (Morrison and Robinson, 1997). More specifically, trust violations stifle mutual support and information sharing in that relationship (Bies and Tripp, 1996), reduce the level of organizational citizenship behavior and job performance (Robinson, 1996), and may lead to low employee morale that adversely affects relationships with customers (Berry, 1999). There is also some indication that when managers are low in behavioral integrity (i.e., the perceived alignment between their words and actions), this characteristic can have a negative effect on the profitability of these organizations (Simons and McLean Parks, 2000; Simons, 2002).

For these reasons, the repair of damaged trust has emerged as a matter of tremendous practical significance. Trust repair can be regarded as a process that reverses the trustor’s confident negative expectations accruing from a violation to the point where he or she is once again willing to be vulnerable to the trustee (Dirks, Lewicki, and Zaheer, 2009; Kramer and Lewicki, 2010). 6 Although this process is regarded as bilateral—involving decisions and actions from both the trustor (the person whose trust has been violated or victim) and trustee (the violator; see Lewicki & Bunker, 1996; Kim, Dirks, & Cooper, 2009)—the bulk of trust repair research has focused on the efficacy of the violator’s responses in the wake of a violation. In a review, Kramer and Lewicki (2010) presented a general typology of likely trustee responses to violations and subsequent efforts to repair trust: social accounts (including explanations and apologies), compensation (including reparations and penance), and structural solutions.

This categorization can be easily integrated with the stages of trust we described earlier. Specifically, CBT relationships are arm’s-length, market oriented, and transaction focused. Trust at this stage relies heavily on a cognitive assessment by the trustee that the benefits of honoring trust will outweigh the costs of damaging it; this type of trust sustains and enhances the trustor’s reliance on the trustee for some valued outcome (which is usually more economic or tangible in nature). Emotional concerns are not irrelevant here; they are merely less salient than cognitive concerns about the tangible costs and benefits of the transaction and loss. Therefore, while trust repair in CBT relationships might be facilitated to some degree by social accounts, greater efficacy in trust repair will result from actual compensation or structural changes that more directly facilitate the achievement of the trustor’s desired (economic) outcome. In short, dealing with the impact of a violation is paramount in violations of CBT.

Similarly, IBT relationships are close interpersonal relationships characterized by a strong emotional bond between the parties. These parties share the same goals and values and mutually demonstrate a strong commitment to continuing and nurturing the relationship to even higher levels. Trust at this stage relies heavily on an emotional assessment that the other party is equally motivated to invest in the relationship. Consequently, as opposed to CBT relationships, cognitive concerns are not irrelevant here, but they are merely less salient than emotional concerns. In this case, one might expect that trust repair is more effective to the extent that the trustee conveys social accounts that reaffirm commitment to the relationship. In short, dealing with the intent of the trustee in the wake of a violation is paramount in violations of IBT.

In the only study to directly test these predictions, Tomlinson, Lewicki, and Wang (2012) examined the independent and combined effects of impact (compensation) and intent (apology, explanation, and promise) tactics to repair both CBT and IBT relationships. They found no significant difference in the effectiveness of impact versus intent tactics for repairing violations in CBT relationships. However, intent tactics (accounts, apologies, verbalizations) were significantly better than impact strategies for repairing violations in IBT. Moreover, across both stages of trust, combining both strategies was found to be more effective than either type alone, suggesting these tactics combine in an additive manner.

We now inventory the remaining trust repair research, finding that the majority of this work has been done on CBT relationships and has examined the impact of all three categories in the Kramer and Lewicki (2010) typology (accounts, compensation, and structural change).

Trust Repair

Most trust repair studies have examined the use of verbal accounts (as opposed to compensation, for example) to repair CBT relationships. This is noteworthy insofar as talk is “cheap”—which is to say that mere words are unsubstantiated by the offender and unverified by the victim (Farrell and Rabin, 1996). According to this view, “a verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on”—a quote attributed to the famous New York Yankees catcher (and “philosopher”) Yogi Berra. An initial study by Bottom, Gibson, Daniels, and Murnighan (2002) found that apologies and simple explanations led to restored cooperation in a prisoner’s dilemma game. Similarly, Tomlinson et al. (2004) found that apologies whereby the offender fully accepted culpability for the violation were significantly related to the victim’s willingness to reconcile after a violation; this beneficial effect was magnified when the receiver judged the apology as sincere and timely.

A subsequent stream of research by Kim and his colleagues (2004) examines the relative effects of apologies versus other types of social accounts. They found that when trust violations were regarded as matters of the violator’s low competence, apologies were more effective than when the offender denied the offense had happened; however, denial was more effective than an apology when the violation was ascribed to the violator’s low integrity. The authors explain this finding by suggesting that breakdowns in competence can often be readily explained (“I made a mistake”) and hence an apology can be effective, while breakdowns in integrity (“I lied” or “I broke my promise’) are less readily fixed by a simple apology, and hence denying the violation might indeed be more effective. They also established that apologies were more effective when there was subsequent evidence of actual guilt; denials were more effective when there was subsequent evidence of innocence.

A subsequent study by Kim, Dirks, Cooper, and Ferrin (2006) examined two types of apologies. In one, the trustee made an internal attribution and admitted full responsibility for the violation, while in the other, the trustee made an external attribution and the “blame” for the violation was deflected away from the trustee. The results support the findings of the earlier study: trust repair was more effective when apologizing with an internal attribution on matters of a competence breakdown, but when there was an integrity breakdown, an apology with an external attribution was more effective.

In a third study, these researchers also explored the viability of a third social accounting device: reticence (silence). They found that reticence (compared to apology and denial) is always a suboptimal response, which is striking given how apparently prevalent silence is in accounting for trust violations committed by highly visible politicians, sports figures, business leaders, and others (Ferrin, Kim, Cooper, and Dirks, 2007). To the extent that apologies influence trust repair, they appear to signal repentance (Dirks, Kim, Ferrin, and Cooper, 2011). That is, they are construed by receivers as evidence that the offender is remorseful enough over the violation to the point that this person pledges to reform his or her behavior in subsequent interactions.

Interestingly, not all trust repair research has supported the efficacy of mere apologies (i.e., admission of responsibility and expression of regret) in CBT relationships. Because some researchers contend that apologies are distinct from other types of accounts (such as promises of future trustworthy behavior, hence manifesting a signal of repentance without actually apologizing for past behavior), their effects have been examined independently. Schweitzer et al. (2006) found that apologies did not influence trust repair, but promises of future trustworthy behavior significantly accelerated this process when the violator displayed a pattern of trustworthy behavior after the violation (as long as the victim did not perceive any deception). Similarly, Tomlinson (2012) separated the effects of apologies and promises and found that promises (but not apologies) were predictive of postviolation trust.

Despite the conceptual distinction between an apology and other verbal accounts, Polin, Lount, and Lewicki (2012) recognized six potential components of a fully effective apology: expression of regret for the violation, explanation of why the violation occurred, acknowledgment of responsibility for causing the violation, declaration of repentance (intent to not commit the violation in the future), offer of repair (for damage created by the violation), and request for forgiveness. They found that an apology that included more of these elements was more effective in stimulating trust repair than one including fewer components. They also replicated the findings of Kim, Ferrin, Cooper, and Dirks (2004) showing that apologies were more effective for competence violations compared to integrity violations; yet they also found that more complete apologies were more effective than less complete apologies for integrity violations as well.

Kramer and Lewicki (2010) also recognized that trustees might attempt to repair trust using strategies that rely more on actions than words. Bottom et al. (2002) found that penance (financial compensation for damage created by the violation) had an even greater effect on restored cooperation than apologies and explanations alone. Moreover, the actual size of the penance mattered less than whether the violator offered the penance voluntarily, combined with some degree of linguistic finesse in explaining it (i.e., “What can I do?” was superior to, “What will it take?”). Similarly, Desmet, De Cremer, and van Dijk (2011) found that financial overcompensation after a violation led to greater trust repair as long as the offense was not regarded as being due to the trustee’s malevolent intentions (e.g., deception). Much like apologies, substantive penance can signal repentance. Yet once again, repentance is more effective for violations of competence than integrity; that is, penance did not repair trust after intentional deception.

The final category to repair trust presented by Kramer and Lewicki (2010) is to change the structure of the situation so as to minimize trust violations in the future. As with accounts and reparations, the volitional nature of a structural change by the trustee is pivotal. One key study on this tactic did not focus on interpersonal trust per se but does empirically demonstrate the basic dynamic. Nakayachi and Watabe (2005) examined the effect of hostage posting on trust repair. Hostage posting refers to a self-sanctioning system whereby the trustee voluntarily accepts monitoring by the trustor and, if a violation occurs, penalties. These researchers found that hostage posting facilitates trust repair by removing the trustee’s incentive for untrustworthy behavior because he or she has agreed to be regularly monitored. Similarly, regulation is a tactic that focuses on altering the situation to make trust more likely to be honored in subsequent interactions because critical behaviors are monitored and punishable if they occur. Regulation can also signal the trustee’s repentance (Dirks et al., 2011).

Thus, violations of CBT can be repaired when the offender gives a timely, sincere, and complete apology (e.g., complete apologies include explicit promises of future trustworthiness). Trust repair can be further accelerated by other congruent tactics such as compensation or structural changes. As long as these tactics are seen as volitional and indicating repentance, they are likely to boost the likelihood of trust repair. However, boundary conditions do seem to exist. When there is reason to believe that deception or malevolent intent drives the violation, or when the violation is regarded as a matter of low integrity instead of low competence, such matters appear to be more resistant to repair. Similarly, violations that are more severe appear to be harder to repair (Tomlinson, 2012; Tomlinson et al., 2004).

If relationships are established that are high in IBT, there is also a higher level of emotional investment. In these relationships, trust violations contain both an affective and a practical component. Once a shared identity has been established, any disconfirming trust violation can be viewed as a direct challenge to the trustor’s (victim’s) most central and cherished values (Lewicki and Bunker, 1995), and it may also represent conflict with the trustor’s psychological orientation (Deutsch, 1985). The trustor is likely to feel upset, angry, violated, or even foolish if loss of face is a result of trusting the other when trusting turned out to be inappropriate. In cases where IBT is violated, we argue that reparative effort must at least be attempted for a high-IBT relationship to have even a chance of continuing. A number of studies have shown that when parties (particularly those in a close relationship) cannot or will not communicate about a major problem in their relationship, they are more likely to end the relationship than continue interacting (Courtright, Millar, Rogers, and Bagarozzi, 1990; Gottman, 1979; Putnam and Jones, 1982).

We envision three stages to the process of restoring IBT trust. First, the parties exchange information about the perceived trust violation (Lewicki and Bunker, 1996). From the Tomlinson et al. (2012) study, we noted that strategies that attempted to address the intent of the violation were more effective for repairing IBT. Thus, parties should attempt to identify and understand the act that was perceived as violation. Miscommunication and misunderstandings are often cleared up at this stage. A husband might accuse his wife of admiring another man at a party, perceiving this to be an uncharacteristic violation of the IBT he has for her and the integrity of their marriage. When the wife explains that she was merely admiring the man’s sweater and thinking of purchasing a similar one for her husband, it might transform the husband’s perception of an IBT trust violation. An explanation that the act either was not what he perceived it to be or that the motivation for the act was consistent with his expectations of his wife’s commitment to their relationship may be adequate to restore the IBT relationship. (However, if this pattern persists whenever the couple is out together, the wife’s explanation will cease to be adequate over time.)

Second, the violated party must be willing to forgive rather than to engage in other forms of reaction to trust betrayal (see McCullough, Pargament, and Thoresen, 2000; Finkel, Rusbult, Kumashiro, and Hannon, 2002, for reviews). Research reveals that the victim’s commitment to the relationship plays an important role. Commitment occurs as a result of high satisfaction with the relationship, increasing investments in the relationship by the victim, and the declining availability or suitability of alternative relationships to meet important needs. When the victim is highly committed to the relationship (as measured by these indicators), he or she is far more willing to forgive than to experience negative feelings, make negative attributions to the violator, or engage in behaviors such as revenge or retaliation toward the violator (Finkel et al., 2002; Tomlinson, 2011).

In the final communication stage, the parties reaffirm their commitment to a high-IBT relationship. They may affirm similar interests, goals, and actions (Lewicki and Stevenson, 1998) and explicitly recommit to the relationship. They may also explicitly realign their psychological orientations to each other (Deutsch, 1985) and discuss strategies to avoid similar misunderstandings, miscommunications, or disconfirmations in the future.

However, when the parties either fail to reconcile the trust violation within their shared identity or are unable to do so, high-IBT relationships may be transformed to low IBT or even IBD. If the violation is largely inconsistent with the core beliefs and values of one of the partners and cannot be adequately explained within the context of the current relationship, then the parties must elect to either renegotiate their shared identity or terminate the high-IBT relationship (Larson, 1993).

Naturally not every IBT relationship is as all-encompassing as a marriage. But there are business and professional relationships where the same dynamics apply. One worker may take another into confidence and share strong dissatisfaction with the boss’s behavior, only to discover that the coworker has told the boss about the negative comments. A student may ask a favorite teacher to read some poetry that the student has written and later discover that the teacher published the poetry under his own name. Thus, no model of trust restoration can explain the idiosyncrasies of each individual relationship. Our intent is merely to explore the dynamics of trust restoration within the context of various kinds of relationship, to better understand the link between relationship and trust type.

Strategies of trust restoration necessarily differ with the kind of relationship the parties have. For example, research has demonstrated that people who perceive few alternatives to their existing relationship or experience a high degree of interdependence may continue the relationship with the partner despite repeated or even violent trust violations (Rusbult and Martz, 1995; Tomlinson, 2011). It may also be that those who are heavily invested in high-IBT relationships are actually less sensitive to trust violations (Robinson, 1996).

Despite the generally negative affect associated with distrust, we should note that trust restoration is not always a desirable alternative. Distrust is necessary when people perceive a need to protect themselves or others from possible harm or when other parties in the relationship are not well known (Lewicki et al., 1998). Some work teams also perform better in CBD situations, perhaps because each member takes more care to ensure that the partners perform as expected. This self-policing contributes to higher product quality.

Implications for Managing Conflict More Effectively

Some of what we have said about trust we have known for a long time, but other parts are quite new and somewhat speculative. They remain to be validated through further research on how people develop and repair trust in their relationships. By way of summarizing this chapter, we make some statements about trust and its implications for managing conflict:

- The existence of trust between individuals makes conflict resolution easier and more effective . This point is obvious to anyone who has been in a conflict. A party who trusts another is likely to believe the other’s words and assume that the other will act out of good intentions, and probably look for productive ways to resolve a conflict should one occur. Conversely, if one distrusts another, one might disbelieve the other’s words, assume that the other is acting out of dark intentions, and defend oneself against the other or attempt to beat and conquer the other. As we have tried to indicate several times in this chapter, the level of trust or distrust in a relationship therefore definitively shapes emergent conflict dynamics.

- Trust is often the first casualty in conflict. If trust makes conflict resolution easier and more effective, eruption of conflict usually injures trust and builds distrust. It does so because it violates the trust expectations, creates the perception of unreliability in the other party, and breaks promises. Moreover, the conflict may serve to undermine the foundations of identification-based trust that may exist between the parties. Thus, as conflict escalates, for whatever reason or cause, it serves to decrease trust and increase distrust. The deeper the distrust that is developed, the more the parties focus on defending themselves against the other or attempting to win the conflict, which further serves to increase the focus on distrust and decrease actions that might rebuild trust.

- Creating trust in a relationship is initially a matter of building calculus-based trust . Many of those writing on trust have suggested that one of the objectives in resolving a conflict is to “build trust.” Yet in spite of these glib recommendations, few authors are sufficiently detailed and descriptive of those actions required to actually do so. From our review of the literature and the research we have reported in this chapter, it is clear to us that to build trust, a party must begin with the actions we outline in this chapter: act consistently and reliably, meet deadlines and commitments, and repeatedly do so over time or over several bands of activity in the relationship.

- Relationships can be strengthened if the parties are able to build identification-based trust . Strong calculus-based trust is critical to any stable relationship, but IBT (based on perceived common goals and purposes, common values, and common identity) is likely to strengthen the overall trust between the parties and the ability of the relationship to withstand conflict that may otherwise be relationship fracturing. If the parties perceive themselves as having strong common goals, values, and identities, they are motivated to sustain the relationship and find productive ways to resolve the conflict so that it does not damage the relationship.

- Relationships characterized by calculus-based or identification-based distrust are likely to be conflict laden, and eruption of conflict within that relationship is likely to feed and encourage further distrust . At the calculus-based level, the actor finds the other’s behavior (at least) unreliable and unpredictable, and the other’s intentions and motivations might be seen as intentionally malevolent in nature. At the identification-based level, the actor believes that he and the other are committed to dissimilar goals, values, and purposes and might thus attribute hostile motives and intentions to the other. Once such negative expectations are created, actions by the other become negative self-fulfilling prophecies (“I expect the worst of the other, and his behavior confirms my worst fears”), which often lead the conflict into greater scope, intensity, and even intractability.

- Most relationships are not purely trust and distrust but contain elements of both . As a result, we have positive and negative feelings about the other, which produces another level of conflict, an intrapsychic conflict often called “ambivalence.” States of ambivalence are characterized by elements of both trust and distrust for another; the internal conflict created by that ambivalence serves to undermine clear expectations of the other’s behavior and force the actor to scrutinize every action by the other to determine whether it should be counted in the trust or the distrust column. Ambivalent relationships are often finely grained and finely differentiated (Gabarro, 1978) because the actor is forced to determine the contexts in which the other can be trusted and those in which the other should be distrusted. As noted elsewhere (Thompson, Zanna, and Griffin, 1995; Lewicki and McAllister, 1998), ambivalence can lead actors to become incapacitated in further action or modify strategies of influence with the other party. Thus, an actor’s internal conflict between trust and distrust probably also affects how he handles the interpersonal conflict between himself and the other party. Because of the number of bands in the bandwidth of a relationship and the ways in which trust and distrust can mix in any given relationship, we also argue that relationships holding varied degrees of ambivalence are far more common than relationships characterized by “pure” high trust or high distrust.

- It is possible to repair trust—although it is easier to write about the steps of such repair than to actually perform it . Effective trust repair is often a key part of effective conflict resolution. In the preceding section of this chapter, we discussed some of the steps necessary to repair trust. Three major strategies were identified: providing a social account (e.g., apology) that explains the violation and verbally attempts to minimize the trust damage created by the violation; providing penance to economically compensate the victim for the tangible costs of the trust violation; and introducing structural changes or rules and regulations that attempt to minimize the likelihood of trust violations in the future. Research into the effectiveness of these strategies is growing, and more work is necessary to identify which strategies are likely to be more effective given different types of violations.

Repairing trust may take a long time because the parties have to reestablish reliability and dependability that can occur only over time. Therefore, although rebuilding trust may be necessary for effective conflict resolution in the relationship over the long run, addressing and managing the distrust may be the most effective strategy for short-term containment of conflict. By managing distrust, we engage in certain activities:

- We explicitly address the behaviors that created the distrust. These may be actions of unreliability and undependability, harsh comments and criticism, betrayal of previous agreements, or aggressive and antagonistic activities occurring as the conflict escalated.

- If possible, each person responsible for a trust violation or act of distrust should apologize and give a full account of the reasons for the trust violation. Acknowledging responsibility for actions that created the trust violation, and expressing regret for harm or damage caused by the violation, is often a necessary step in reducing distrust. Alternative actions, such as penance and structural approaches to minimizing trust violations, may also be necessary.

- We restate and renegotiate the expectations for the other’s conduct in the future. The parties have to articulate expectations about the behavior that needs to occur and commit to those behaviors in future interactions.

- We agree on procedures for monitoring and verifying the designated actions to ensure that commitments are being met.

- We simultaneously create ways to minimize our vulnerability or dependence on the other party in areas where distrust has developed. This often occurs as the vulnerable parties find ways to ensure that they are no longer vulnerable to the other’s exploitation or identify alternative ways to have their needs met. If one person depends on another for a ride to work and the driver is consistently late or occasionally forgets, then even if the actor accepts the other’s apology and commitment to be more reliable, the actor may also explore alternative ways to get to work.

CONCLUSION

In this chapter, we have described the critical role that trust and distrust play in relationships. We have reviewed some of the basic research on trust and elaborated on the types of trust that exist in most interpersonal relationships. We have suggested that trust and distrust coexist in most relationships, that trust and distrust can be calculus based or identification based, and that relationships differ in form and character as a function of the relative weight of the two types of trust in the relationship. Finally, we have suggested that managing any relationship requires us to both create trust and manage distrust effectively. These processes are most critical when trust is broken and needs to be repaired. A great deal of research remains to be done on these propositions, but we hope that the ideas proposed in this chapter serve to move this work forward.

Notes

References

Atkinson, S., and Butcher, D. “Trust in Managerial Relationships.” Journal of Managerial Psychology , 2003, 18 , 282–304.

Bachmann, R., and Zaheer, A. Handbook of Trust Research . Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2006.

Bachmann, R., and Zaheer, A. Landmark Papers on Trus t. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2008.

Berry, L. L. (1999). Discovering the Soul of Service . New York: Free Press.

Bies, R. J., and Tripp, T. M. “Beyond Distrust: Getting Even and the Need for Revenge.” In R. Kramer and T. R. Tyler (eds.), Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996.

Bigley, G. A., and Pearce, J. L. “Straining for Shared Meaning in Organization Science: Problems of Trust and Distrust.” Academy of Management Review , 1998, 23 , 405–422.

Blois, K. “Is It Commercially Responsible to Trust?” Journal of Business Ethics , 2003, 45 , 183–193.

Boon, S. D., and Holmes, J. G. “The Dynamics of Interpersonal Trust: Resolving Uncertainty in the Face of Risk.” In R. A. Hinde and J. Groebel (eds.), Cooperation and Prosocial Behavior . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Bottom, W. P., Gibson, K., Daniels, S., and Murnighan, J. K. “When Talk Is Not Cheap: Substantive Penance and Expressions of Intent in Rebuilding Cooperation.” Organization Science , 2002, 13 , 497–513.

Brewer, M., and Kramer, R. “Choice Behavior in Social Dilemmas: Effects of Social Identity, Group Size and Decision Framing.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 1986, 50 , 543–549.

Butler, J. K. “Toward Understanding and Measuring Conditions of Trust: Evolution of Conditions of Trust Inventory.” Journal of Management , 1991, 17 , 643–663.

Butler, J. K. “Behaviors, Trust and Goal Achievement in a Win-Win Negotiating Role Play.” Group and Organization Management , 1995, 20 , 486–501.

Caldwell, C., and Karri, R. “Organizational Governance and Ethical Systems: A Covenantal Approach to Building Trust.” Journal of Business Ethics , 2005, 58 , 249–259.

Chaiken, S. L. “Physical Appearance and Social Influence.” In C. P. Herman, M. P. Zanna, and E. T. Higgins (eds.), Physical Appearance, Stigma, and Social Behavior: The Ontario Symposium . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1986.

Colquitt, J., Scott, B. A., and LePine, J. A. “A Meta-Analytic Test and Extension of an Integrative Model of Trust.” Journal of Applied Psychology , 2007, 92 , 909–927.

Courtright, J. A., Millar, F. E., Rogers, L. E., and Bagarozzi, D. “Interaction Dynamics of Relational Negotiation: Reconciliation versus Termination of Distressed Relationships.” Western Journal of Speech Communication , 1990, 54 , 429–453.

Currall, S. C., and Inkpen, A. C. “On the Complexity of Organizational Trust: A Multi-Level Co-Evolutionary Perspective and Guidelines for Future Research.” In R. Bachmann and A. Zaheer (eds.), A Handbook of Trust Research . Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2006.

De Cremer, D., and van Knippenberg, D. “Cooperation as a Function of Leader Self-Sacrifice, Trust and Identification.” Leadership and Organization Development Journal , 2005, 26 , 355–369.

Desmet, P. T., De Cremer, D. E., and van Dijk, E. “In Money We Trust? The Use of Financial Compensations to Repair Trust in the Aftermath of Distributive Harm.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 2011, 114 , 75–86.

Deutsch, M. “A Theory of Cooperation and Competition.” Human Relations , 1949, 2 , 129–151.

Deutsch, M. “Trust and Suspicion.” Journal of Conflict Resolution , 1958, 2 , 265–279.

Deutsch, M. “The Effect of Motivational Orientation upon Trust and Suspicion.” Human Relations , 1960, 13 , 123–139.

Deutsch, M. “Cooperation and Trust: Some Theoretical Notes.” In M. R. Jones (ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation 1962 . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1962.

Deutsch, M. “Interdependence and Psychological Orientation.” In M. Deutsch, Distributive Justice: A Social Psychological Perspective . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985.

Dirks, K., and Ferrin, D. “The Role of Trust in Organizational Settings.” Organization Science , 2001, 12 , 450–467.

Dirks, K., Kim, P., Ferrin, D. L., and Cooper, C. D. “Understanding the Effects of Substantive Responses on Trust following a Transgression.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 2011, 114 , 87–103.

Dirks, K., Lewicki, R. J., and Zaheer, A. “Repairing Relationships within and between Organizations: Building a Conceptual Foundation.” Academy of Management Review , 2009, 34 , 68–84.

Dunn, J. R., and Schweitzer, M. E. “Emotion and Trust.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 2005, 33 , 736–748.

Farrell, J., and Rabin. M. “Cheap Talk.” Journal of Economic Perspectives , 1996, 10 , 103–118.

Ferrin, D. L., Kim, P. H., Cooper, C. D., and Dirks, K. T. “Silence Speaks Volumes: The Effectiveness of Reticence in Comparison to Apology and Denial for Repairing Integrity- and Competence-Based Trust Violations.” Journal of Applied Psychology , 2007, 92 , 893–908.

Ferris, G. R., Blass, F. R., Douglas, C., Kolodinsky, R. W., and Treadway, D. C. “Personal Reputation in Organizations.” In J. Greenberg (ed.), Organizational Behavior: The State of the Science (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2003.

Finkel, E. J., Rusbult, C. E., Kumashiro, M., and Hannon, P. A. “Dealing with Betrayal in Close Relationships: Does Commitment Promote Forgiveness?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 2002, 82 , 956–974.

Fisher, R., Ury, W., and Patton, B. Getting to Yes . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

Foeman, A. K. “Managing Multiracial Institutions: Goals and Approaches for Race-Relations Training.” Communication Education , 1991, 40 , 255–265.

Gabarro, J. J. “The Development of Trust Influence and Expectations.” In A. G. Athos and J. J. Gabarro (eds.), Interpersonal Behavior: Communication and Understanding in Relationships . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1978.

Gambetta, D. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations . Boston: Blackwell, 1988.

Glick, S., and Croson, R. (2001). Reputations in negotiation. In S. Hoch and H. Kunreuther (eds.), Wharton on Making Decisions . New York: Wiley, 2001.

Goel, S., Bell, G., and Pierce, J. L. “The Perils of Pollyanna: Development of the Over-Trust Construct.” Journal of Business Ethics , 2005, 58 , 203–218.

Gottman, J. M. Marital Interaction: Experimental Investigations . Orlando, FL: Academic Press, 1979.

Han, G., and Harms, P. D. “Team Identification, Trust and Conflict: A Mediation Model.” International Journal of Conflict Management , 2010, 21 , 20–43.

Huston, T. L., and Levinger, G. “Interpersonal Attraction and Relationships.” Annual Review of Psychology , 1978, 29 , 115–156.

Jeffries, F. L., and Reed, R. “Trust and Adaptation in Relational Contracting.” Academy of Management Review , 2000, 25 , 873–882.

Jennings, E. E. Routes to the Executive Suite . New York: McGraw-Hill, 1971.

Jones, G. R., and George, J. M. “The Experience and Evolution of Trust: Implications for Cooperation and Teamwork.” Academy of Management Review , 1998, 23 , 531–546.

Jones, R. A., and Brehm, J. W. “Attitudinal Effects of Communicator Attractiveness When One Chooses to Listen.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 1976, 6 , 64–70.

Jones, W. H., and Burdette, M. P. “Betrayal in Relationships.” In A. L. Weber and J. H. Harvey (eds.), Perspectives on Close Relationships . Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 1994.

Kanter, D. L., and Mirvis, P. H. The Cynical Americans: Living and Working in an Age of Discontent and Disillusion . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1989.

Kim, P., Dirks, K., and Cooper, C. D. “The Repair of Trust: A Dynamic Bilateral Perspective and Multilevel Conceptualization.” Academy of Management Review , 2009, 34 , 401–422.

Kim, P. H., Dirks, K. T., Cooper, C. D., and Ferrin, D. L. “When More Blame Is Better Than Less: The Implications of Internal vs. External Attributions for the Repair of Trust after a Competence- vs. Integrity-Based Violation.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 2006, 99 , 49–65.

Kim, P, Ferrin, D. L., Cooper, C. D., and Dirks, K. T. “Removing the Shadow of Suspicion: The Effects of Apology versus Denial for Repairing Competence-versus Integrity-Based Trust Violations.” Journal of Applied Psychology , 2004, 89 , 104–118.

King-Casas, B., Tomlin, D., Anen, C., Camerer, C., Quartz, S., and Montague, P. R. “Getting to Know You: Reputation and Trust in a Two-Person Economic Exchange.” Science , 2005, 308 , 7883.

Kramer, R. M. “Divergent Realities and Convergent Disappointments in the Hierarchic Relation: Trust and the Intuitive Auditor at Work.” In R. M. Kramer and T. R. Tyler (eds.), Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996.

Kramer, R. “Identity and Trust in Organizations: One Anatomy of a Productive but Problematic Relationship.” In M. Hogg and D. J. Terry (eds.), Social Identity Processes in Organizational Contexts . Philadelphia: Psychology Press, 2001.

Kramer, R. “When Paranoia Makes Sense.” Harvard Business Review , 2002, July, 5–11.

Kramer, R. “Trust as Situated Cognition: An Ecological Perspective on Trust Decisions.” In R. Bachmann and A. Zaheer (eds.), Handbook of Trust Research . Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2006.

Kramer, R. M., and Cook, K. S. Trust and Distrust in Organizations: Dilemmas and Approaches . New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004.

Kramer, R., and Lewicki, R. “Repairing and Enhancing Trust: Approaches to Reducing Organizational Trust Deficits.” Academy of Management Annals , 2010, 4 , 245–277.

Kramer, R., and Tyler, T. R. (eds.). Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996.

Larson, J. M. “Exploring Reconciliation.” Mediation Quarterly , 1993, 11 , 95–106.

Lewicki, R. J., Barry, B., and Saunders, D. Negotiation . (6th ed.) Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill Irwin, 2010.

Lewicki, R. J., and Bunker, B. B. “Trust in Relationships: A Model of Development and Decline.” In B. B. Bunker and J. Z. Rubin (eds.), Conflict, Cooperation, and Justice: Essays Inspired by the Work of Morton Deutsch . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995.

Lewicki, R. J., and Bunker, B. B. “Developing and Maintaining Trust in Work Relationships.” In R. Kramer and T. R. Tyler (eds.), Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996.

Lewicki, R. J., and McAllister, D. J. “Confident Expectations and Reasonable Doubts: The Social Dynamics of Ambivalence in Interpersonal Relationships.” Paper presented to the Conflict Management Division, Academy of Management National Meetings, San Diego, 1998.

Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., and Bies, R. J. “Trust and Distrust: New Relationships and Realities.” Academy of Management Review , 1998, 23 , 438–458.

Lewicki, R. J., and Stevenson, M. A. “Trust Development in Negotiation: Proposed Actions and a Research Agenda.” Business and Professional Ethics Journal , 1998, 16 , 99–132.

Malhotra, D. “Trust and Reciprocity Decisions: The Differing Perspectives of Trustors and Trusted Parties.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 2004, 94 , 61–73.

McAllister, D. J. “Affect-and Cognition-Based Trust as Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organizations.” Academy of Management Journal , 1995, 38 , 24–59.

McCullough, M. E., Pargament, K. I., and Thoresen, C. E. Forgiveness: Theory, Research and Practice . New York: Guilford Press, 2000.