CHAPTER SIX

POWER AND CONFLICT

Peter T. Coleman

In the Sonagachi red-light district in Calcutta, India, prostitutes have organized to mobilize against AIDS, altering the power structure by challenging any pimp or madam who would insist on a customer’s right to sex without a condom.

At a company in the United States, in an attempt to avoid layoffs, the great majority of employees agreed to cut their own salaries by 20 percent; the CEO rejected the offer and chose instead to fire 20 percent of the workforce, stating that “it was very important that management’s prerogative to manage as it saw fit not be compromised by sentimental human considerations” (Harvey, 1989, p. 275).

In the wilds of Wyoming, groups of ranchers and environmentalists, historically bitter adversaries, have teamed up to fight the problems posed by an increase in the population of wolves in their neighboring national parks.

All of these conflicts have one basic element in common: power. Power to challenge, power to resist, and power through cooperating together. In fact, virtually all conflicts directly or indirectly concern power. Conflict is often a means of seeking or maintaining the balance or imbalance of power in relationships. It may also be waged as a symbolic expression of one’s identity and right to self-determination. Power is commonly used in conflict as leverage for achieving one’s goals. It influences the types of conflicts to which people of differing levels of power are more or less frequently exposed to, as well as the relative availability of the strategies and tactics employed. The powerful also largely determine what is considered to be important, fair, and just in most settings and thus shape and control many methods of resolution. Of course, changes in power, particularly when they are dramatic, can also affect conflict, with substantial impacts on people’s motivations, aspirations, and tactics. Because of its ubiquity, it is paramount that when we address conflict, we consider power.

This chapter provides an overview of some key components of the relationship between power and conflict. It is organized in five sections, beginning with a discussion of the dimensions of power that are important when considering conflict and its constructive resolution. In the second section, I describe some of the personal and environmental factors that research has shown affect people’s behavioral tendencies and responses to power in social relations. In the third section, I discuss the relevance of these ideas to conflict resolution, examining some of the principles of the dynamics of power and conflict and outlining the tendencies of members of both high-power and low-power groups in conflict. I then describe a new situated model of power and conflict, before concluding by discussing the implications of these ideas for training in conflict resolution.

A DISCUSSION OF POWER

Bertrand Russell wrote, “The fundamental concept in social science is power, in the same sense in which energy is the fundamental concept in physics” (1938, p. 4). Despite its pervasive role in social relations, power has proven to be a particularly difficult and elusive concept. There are many treatments of it in the social sciences. It has been conceptualized alternatively in terms of sources of power (Depret and Fiske, 1993; Emerson, 1962; Fiske and Berdahl, 2007; Kipnis, 1976; Thibaut and Kelley, 1959), the capacity to bring about effects (Boulding, 1990; Cartwright, 1959, 1965; Coleman, 2004; Follet, 1924/1973; French and Raven, 1959; Lewin, 1943; Pfeffer, 1981; Rummel, 1976; Weber, 1914/1978), influential actions (Deutsch, 1973; Foucault, 1984; Zartman and Rubin, 2002), and its resultant effects (Dahl, 1957; Russell, 1938; Simon, 1957). Clearly, power means different things to different people.

Even once power is defined, its meaning often remains mercurial. For instance, if power is defined as “a capacity to produce effects,” its effects can be intentional or unintentional; it can be employed effectively or ineffectively in achieving goals; it can be associated with a wide variety of sources, strategies, and tactics, all with different qualities and consequences, and these qualities and consequences can vary dramatically across contexts and cultures. This capacity can also vary in terms of its relative (local) or absolute nature, be associated with helping or harming others, and be of a hard (military, economic) or soft (attractive) nature (Nye, 1990). Such nuance and complexity of meaning has resulted in a long list of (sometimes contradictory) definitions and operationalizations of power in theory and research and more than a fair amount of confusion.

Despite the conceptual challenges the construct of power presents, research on power in social conflict has increased considerably over the past decade (Fiske and Berdahl, 2007). This research has focused primarily on the effects of high versus low power in relation to others on perceptions, emotions, and behaviors (Galinsky, Magee, Gruenfeld, Whitson, and Liljenquist, 2008; Magee and Galinsky, 2008; Rouhana and Fiske, 1995; Rubin and Brown, 1975; Tjosvold, 1981, 1991; Tjosvold and Wisse, 2009; Zartman and Rubin, 2002), and has typically operationalized power as some form of independence from others in social relations (e.g., Kim, Pinkley, and Fragale, 2005). Although this body of research has advanced our understanding a great deal, it has been critiqued on three grounds: (1) it tends to atomize and decontextualize related aspects of social power, thus removing each element from the relations and contexts that imbue them with meaning; (2) it focuses primarily on the short-term effects of independent variables on outcomes and neglects the study of power dynamics over time; and (3) it generally neglects the positive side of power dynamics in social relations or, for that matter, the complications posed when holding mixed motives such as greed and guilt when wielding power (Fiske and Berdahl, 2007).

Nevertheless, the literature on social power that has accumulated over many decades has identified a number of important distinctions that can help us to better specify and comprehend power. We next look at these.

Power as a Dynamic

Power is often attributed to people as a stable characteristic (“Donald Trump is a very powerful person”). However, the ability to make things happen is most often determined not only by people but by the dynamic interaction of particular people behaving in a certain manner in a given situation. Accordingly, Deutsch (1973) described power as a relational concept functioning between the person and his or her environment. Power therefore is determined not only by the characteristics of the person or persons involved in any given situation or solely by the characteristics of the situation, but by the interaction of these two sets of factors. The power of the Indian prostitutes, for example, can be seen as the result of their ability to organize and mobilize their colleagues in this particular setting where demand for their services was high.

Environmental, Relational, and Personal Power

Deutsch (1973) also offered a distinction among three specific meanings of power: environmental power , the degree to which an individual can favorably influence his or her overall environment; relationship power , the degree to which a person can favorably influence another person; and personal power , the degree to which a person is able to satisfy his or her own desires. These three meanings for power may be positively correlated (e.g., high relationship power equals high personal power), but this is not necessarily so. The CEO mentioned at the beginning of the chapter may have had more relationship power than his employees in that situation (in terms of his power over their jobs) and so could resist their attempts to influence the layoff decision, but by doing so and firing 20 percent of the workers, he may well have sacrificed environmental power (his company’s efficiency or market share) given the effects of his actions on the morale and commitment of the remaining employees. This loss of environmental power could result in diminution of the CEO’s personal power, if it adversely affects his sense of self-efficacy, self-esteem, or even personal income. The important point is that these are three distinct but interrelated realms of power: a shift in one type of power (relationship) may result in a gain or loss of another type (personal or environmental) depending on the people and circumstances.

Potential and Kinetic Power

Lewicki, Litterer, Minton, and Saunders (1994) distinguish three aspects of power: power bases, power use, and influence strategies. Power bases are the resources for power or the tools available to influence one’s environment, the other party, or one’s own desires. This is potential power. There exist in the literature many typologies of the bases of power: wealth, social capital, physical strength, weapons, intelligence, knowledge, legitimacy, respect, affection, organizational skills, allies, and so on. These typologies can be useful for discerning different resources for power, but they should not be confused with the enactment of power. Kinetic power involves the active employment of strategies and tactics of influence, which are the manner in which the resources are put to use to accomplish particular objectives. Lewicki et al. (1994) identified such diverse strategies as persuasion, exchange, legitimacy, friendliness, ingratiation, praise, assertiveness, inspirational appeal, consultation, pressure, and coalitions.

Primary and Secondary Power

Power can be seen as operating at two distinct levels—one determining the nature of the interactions among players on the field and one determining the nature of the field itself (Voronov and Coleman, 2003). Secondary power refers to the exercise of power in the conventional sense—the ability to get one’s goals met in a relational context. This can take a coercive or positive form; however, it entails operating in a domain that has already been defined normatively. Primary power refers to the ability to shape the normative domain or affect the sociohistorical process of reality construction (Coleman and Voronov, 2003). This is the process by which our sense of reality, as we know it—our sense of truth, fairness, and justice—is constructed. Deutsch (2004) writes, “The official ideology and myths of any society help define and justify the values that are distributed to the different positions within the society; they codify for the individual what a person in his position can legitimately expect. Examples are legion of how official ideology and myth limit or enhance one’s views of what one is entitled to” (p. 25).

Thus, primary power refers to the ability to affect those activities (e.g., the law, the media, policies) that define the domain. This includes defining what is considered “good” in a society: prosocial versus antisocial forms of violence (e.g., “freedom fighting” versus “terrorism”), morality, religion, ideology, politics, education, and so on. This can be achieved through the blatant tactics used by totalitarian rulers such as Hitler and Stalin or more subtly through political spin, by emphasizing biased accounts of history in schools and textbooks, indirectly controlling or censuring the media, or keeping the judiciary and the legislature in the hands of the dominant group. It is important to recognize that the various sources of power (French and Raven, 1959) are not concrete but are socially constructed. “Legitimacy,” for example, is not objective but is created through management of meaning. Only when the domain has been defined does it become possible for power as conceived in a conventional sense to be exercised. Thus, the two forms of power are interconnected. Primary power opens and constrains the possibilities for exercising secondary power. Secondary power can be seen as expressing and reproducing the status quo of primary power relations. However, secondary power can also contribute to transforming primary power. Revolutions or hostile coups are dramatic examples of secondary power being used in an attempt to transform primary power.

Top-Down, Middle-Out, and Bottom-Up Power

Power in any social system can be the result of resources and influence strategies employed by way of three distinct channels within systems: top down, middle out, and bottom up (Coleman, 2006). Top-down channels are typically used by formal or elite leaders and decision makers (although third parties often employ this channel) and, although they can take many forms, often involve command-and-control strategies of influence that have a rapid and dramatic effect on systems. Middle-out channels reside with the midlevel leaders, managers, and organizations of social systems (such as community-based and nongovernmental organizations) that can influence systems through their social capital and social networks. The influence employed at this level can have a strong effect on systems but typically takes time to unfold. Bottom-up power is the result of changes at the local level (such as changes in individual attitudes or behaviors) that can have a substantial emergent effect on systems but tends to take the longest amount of time to emerge.

Effective Power and Sustainable Outcomes

Having resources and knowledge of influence strategies does not necessarily translate to power; they may be employed more or less effectively in terms of bringing about desired outcomes. Deutsch (1973) outlined the conditions for “effective power” as having control of the resources to generate power, motivation to influence others, skill in converting resources to power, and good judgment in employing power so that it is appropriate in type and magnitude to the situation. However, outcomes can be short or long term. Achieving sustainable outcomes requires both long-term strategic thinking and the ability of power users to read changes in situations, identify negative feedback, and respond adaptively when required (Coleman, 2006).

Perceived Power

Saul Alinsky (1971) said, “Power is not only what you have, but what the enemy thinks you have.” Thus, for power to be effective, it does not necessarily have to be the result of actual resources owned and strategies employed by people but, in some circumstances, by what they are merely perceived to have. In fact, many of those who are less than powerful go out of their way to create an image of power as the critical element of effective influence (Sun Tzu, 1983).

General versus Relevant Power

Often initial assessments of another’s power are erroneous because they are based on aggregates of relative power (the sum total of another’s power in comparison to my own), not on the other’s relevant power resources or the other’s efficacy in implementing the strategies relevant to the interaction at hand (Salacuse, 2001). This typically leads to a sense of overconfidence on the part of general power holders and a sense of helplessness for those in low power.

* * *

In summary, power is dynamic and complex. It can be usefully conceptualized as the ability (or the perception of the ability) to leverage relevant resources in a specific situation in order to achieve personal, relational, or environmental goals, often through using various strategies and channels of influence of both a primary and secondary nature. Now I turn to a discussion of some of the central factors that influence power dynamics in social relations.

COMPONENTS OF POWER

The extensive literature on social power has offered a wide array of conceptual frameworks for studying and analyzing power (see, e.g., Foucault, 1980; Clegg, 1989; Pfeffer, 1981; Blalock, 1989). Here, I employ a rather simple schema to organize a presentation of some of the many factors that research has shown affect people’s orientations and actions with regard to power. The schema, borrowed from social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1999), suggests that human behavior, and in particular human agency, can be understood as the result of dynamic interactions among three sources of influence: personal factors, behavioral patterns, and environmental events. Bandura (1999) writes:

Human behavior has often been explained in terms of unilateral causation, in which behavior is depicted as either being shaped and controlled by environmental influences or driven by internal dispositions. Social cognitive theory explains psychosocial functioning in terms of triadic reciprocal causation. In this model of reciprocal causality, internal personal factors in the form of cognitive, affective, and biological events; behavioral patterns; and environmental events all operate as interactive determinants that influence one another bidirectionally. (p. 23)

This triadic model is consistent with a dynamic view of power and conflict but allows the categorization of factors into the three separate but interrelated categories. I next summarize some of the key personal and environmental factors that can interact to determine people’s behavioral patterns regarding power in social relations.

Personal Factors

Power Orientations.

In his seminal work on power and motivation, McClelland (1975) presented a developmental framework for categorizing people’s experiences and expressions of power. He argued that people everywhere seek power in these ways:

- Support: Obtaining assistance and support from others, often through a dependence relationship. Such relationships can serve to meet the needs of the low-power person, but they can take many forms, from benign and supportive (as in many mentor-mentee relationships) to oppressive and abusive (as with a dictatorial parent). The negative physical and psychological impact of prolonged experiences of dependence and powerlessness by adults has been shown to be dire (Sashkin, 1984) and can lead to a tendency to become more rigid, critical, controlling of others in lower power, and, ultimately, more irrational and violent (Kanter, 1977).

- Autonomy: Establishing one’s autonomy and independence from others. Scholars have referred to this approach as having “power to” or “power from,” in the sense that one has enough power to achieve one’s objectives without being unduly constrained by someone or something else. Individuals who feel empowered in a particular situation have a reduced need for dependence on others, which opens up the possibility of acting independently, thereby bolstering their sense of self-esteem, self-efficacy, and confidence.

- Assertion: Assertively acting on, influencing, and dominating others. This approach to power has been termed power over and is consistent with the popular definition of power as “an ability to get another person to do something that he or she would not otherwise have done” (Dahl, 1968, p. 158). This orientation to power is commonplace and was evident in the earlier example of the CEO and his response to the employees’ initiative.

- Togetherness: Becoming part of an organization or a group. Mary Parker Follett suggested that although power is usually conceived of as power over others, it would also be possible to develop the conception of “power with” others. She envisioned this type as jointly developed, coactive, and noncoercive (Follett, 1973). Bandura (1999) labeled this approach as one of collective agency. This is the form of power illustrated in the vignette about a partnership between ranchers and environmentalists.

McClelland proposed that as people mature, they progress sequentially through each of these stages of development and orientations to power, ideally moving toward the stage of togetherness. This is commensurate with the developmental progression of humans from more egocentric to more sociocentric beings (Piaget, 1937). McClelland also stressed, however, that each of the four power orientations may be useful in any given situation and that problems typically arise for people when they become fixated on any one orientation (such as assertion) or when an individual’s chronic orientation fits poorly with the particular realities or demands of a situation. From this perspective, an individual’s flexibility and responsiveness to changes in his or her environment can be seen as critical to the ability to respond effectively to situations involving power.

For example, returning to the CEO in our earlier example, it is possible that he may have been operating from a chronically assertive orientation to power (power over) and therefore interpreted the employees’ offer as a competitive tactic (“They’re trying to humiliate me or ingratiate themselves”), was motivated to win at all costs, and saw this as morally legitimate because of a belief that low-level employees must make sacrifices for the greater good of the organization. Ultimately, one’s power orientation affects one’s behavior through an assessment of the feasibility of a given action (“Do I have the capacity to act in such a manner, and what will the consequences be?”) unless the orientation is excessively chronic.

Authoritarianism.

A classic area of research that has been found to influence people’s orientations to power is authoritarianism (Adorno, Frenkl-Brunswik, Levinson, and Sanford, 1950), which involves an exaggerated need to submit to and identify with strong authority. Originating from psychodynamic theory, this syndrome is thought to stem from early rearing by parents who use harsh and rigid forms of discipline, demand unquestioning obedience, are overly conscious of distinctions of status, and are contemptuous or exploitative toward those of lower status. The child internalizes the values of the parents and therefore is inclined toward a dominant, punitive approach to power relations. Individuals high in authoritarianism tend to favor absolute obedience to authority and resist personal freedom. These tendencies would most likely orient one toward either authoritarian or submissive orientation to power, depending on the relative status of the other party.

Need for Power.

Need for power (“nPower”; McClelland, 1975; McClelland and Burnham, 1976) has been described as an individual difference where people high on nPower experience great satisfaction in influencing people and arousing strong emotions in them. Individuals high on nPower tend to seek out positions of authority and display a more dominating style in conflict (Bhowon, 2003). This orientation, however, is thought to interact with another personality difference known as “activity inhibition” (see also chapter 17). This is essentially the individual’s level of self-control and general orientation to others. These two traits combine to produce two separate types of power orientation: the personalized power orientation and the socialized power orientation. Individuals high on nPower and low on activity inhibition exhibit a more personalized power orientation, exemplified by a tendency to dominate others in an attempt to satisfy one’s hedonistic desires. Individuals with high nPower and high activity inhibition tend to exhibit socialized power orientation, using power for the good of a cause, an organization, or an institution.

McClelland (1975) postulated that individual power orientations develop through various stages, with the personalized orientation emerging at an earlier stage of development and the socialized orientation at a later stage. This is consistent with Kohlberg’s work on moral development (1963, 1969), which found that individuals in the latter stages of moral development place much higher value on justice, dignity, and equality. The personal-social separation is a useful distinction between the destructive and constructive sides of power; it contradicts the notion of Lord Acton that all power necessarily corrupts.

Ideological Frames.

Burrell and Morgan (1979) identified differences in people’s ideological frames of reference as determining of their approach to power. These frames are comprehensive belief systems about the nature of relations between individuals and society. They classified three types of ideological frames: the unitary, the radical, and the pluralist. From the unitary view , society is seen as an integrated whole where the interests of the individual and society are one and power can be largely ignored and assumed to be used benevolently by those in authority to further the mutual goals of all parties. This perspective is common in collectivist families and cultures and in some benevolent business organizations. In contrast, the radical frame pictures society as comprising antagonistic class interests that are “characterized by deep-rooted social and political cleavages, and held together as much by coercion as by consent” (Morgan, 1986, p. 186). This perspective, epitomized by Marxist doctrine, focuses on unequal distribution of power in society and the significant role that this plays in virtually every aspect of our lives. Finally, the pluralist frame views society as a space where different groups “bargain and compete for a share in the balance of power . . . to realize a negotiated order that creates unity out of diversity” (Morgan, 1986, p. 185). Power is seen as distributed more or less equally among the groups and as the primary medium through which conflicts are resolved. This pluralist view of power is prevalent in the many forms of liberal democracies.

Each distinct ideological frame engenders its own set of expectations about what one can anticipate, what one should attend to, and therefore how one should respond to situations of power and conflict. For example, Stephens (1994) has described how such differences in ideological frames lead various conflict practitioners to use conflict resolution processes to achieve vastly disparate objectives in their work (unitarians favoring maintenance of the status quo of power relations, radicals favoring fundamental systems change and redistribution of power, and pluralists favoring a combination of both, depending on the situation). These translate into significant differences in procedures, such as alternative dispute resolution practices to achieve organizational unity versus peace education and activism to produce community change.

Implicit Power Theories.

Research on implicit power theories (Coleman, 2004) has shed light on a central problem within the power-and-conflict dynamic: the unwillingness of the powerful to share their power (e.g., wealth, information, access, authority) with those in need. Implicit theories are cognitive structures—naive, unarticulated theories about the social world that influence the way people construe events. Research has identified two theories of power that people can hold: a limited-power theory that portrays power as a scarce resource that triggers a competitive orientation to power sharing and an expandable-power theory that views power as an expandable resource and fosters a more cooperative power-sharing orientation. The two competing views of power have been shown to affect people’s decisions and actions on whether to share or withhold resources, as well as the degree to which they involve others in decision-making processes (Coleman, 2004).

Subsequent research on implicit power theories has demonstrated that the social environment can play a critical role in influencing their use by making different theories more or less cognitively salient. For example, in a study conducted in China, participants portraying managers in an organizational simulation were found to share more power (information and assistance) with subordinates when they were led to believe that their organization had a history of approaching organizational power as an expandable resource than when it was portrayed as traditionally viewing and approaching power as a scarce resource (Tjosvold, Coleman, and Sun, 2003). This research emphasizes the critical role the context plays in triggering and fostering differences in implicit theories. Thus, social and organizational structures, norms and climate around empowerment, as well as more informal influences such as myths and legends regarding preferred ways of interacting may be formative and go a long way in providing a context of meaning through which to interpret the value of power sharing.

Social Dominance Orientation.

A more recent model relevant to power and conflict comes from social dominance theory (Sidanius and Pratto, 1999; Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, and Malle, 1994), which contends that societies worldwide organize according to group-based hierarchies, with dominant social groups possessing a disproportionate share of positive social value (wealth, health, status). These hierarchies are maintained by several key factors, including the social dominance orientation (SDO) of members of the groups. SDO is defined as a very general orientation expressing antiegalitarianism; a view of human existence as zero-sum with relentless competition between groups; the desire for generalized, hierarchical relationships between groups; and a desire for in-group dominance over out-groups. The research on SDO has identified consistent gender differences in women’s and men’s levels of SDO (Sidanius, Pratto, and Bobo, 1994), with men having significantly higher levels of SDO than women do. We could expect this type of general orientation to group relations to contribute to a chronically competitive orientation (assertion) to power differences.

* * *

Other individual differences—as wide ranging as interpersonal orientation (high or low sensitivity to others), Machiavellianism, interpersonal trust, and gender—are relevant to discussing people’s orientation to power, but space does not allow for further elaboration (see Lewicki et al., 1994, for a discussion of these variables). Each of the distinct personal factors described here can work in concert to contribute to a chronic orientation and fixation on any one of the power orientations (such as powerlessness). These orientations affect how people perceive conflict, how they evaluate authority relations, and ultimately the decisions and responses they make to power differences in conflict situations. However, except for extreme cases, the influences of these individual difference factors need to be understood as operating in interaction with the individual’s environment.

Environmental Factors

Again, the environmental factors affecting personal differences and behavioral patterns regarding power are innumerable (see Deutsch, 2004, and Blalock, 1989, for summaries). The following sections examine a few major factors.

Deep Structure.

A few scholars propose that the deep structure of most conflicts is dictated by preexisting power relations (Chomsky, 2002). This structure, established through past relations between the parties, their differential access to resources, and existing norms and roles, has been historically constructed. This history is composed of the decisions and actions, victories and defeats, justices and injustices experienced by those who came before us: members of our families, our gender, our communities, our race, our nation, and so on. These cumulative experiences in many ways have defined the rules of the power game. This perspective emphasizes the influences exerted on power by such factors as class and race relations, intergroup conflicts of interest and social competition, inequity between social groups on highly valued dimensions, opportunity structures and the educational systems that perpetuate them, the relative stability of status and power differences, and the perceived legitimacy of all of these factors. Understanding the historical context encourages us to look beyond the current surface manifestations of secondary power and into the processes of primary power. From this perspective, people are seen as agents or carriers of power relations embedded in the wider structure of history and society. They can learn to understand the rules but are rarely able to change them significantly.

Culture.

The culture in which we are immersed is another important influence on our experience of power. Hofstede (1980) identified power distance as a dimension of social relations that is determined by and varies across cultures. He defined it as the extent to which the less powerful persons in a society accept inequality in power and consider it normal. Hofstede argued that inequality exists within every culture, but the degree to which society tolerates it varies from one culture to another. So, for example, in some high-power-distance cultures, such as in parts of India, the notion of empowering employees through participation in decisions and delegation of authority is considered inappropriate and insubordinate by the employees themselves. This cultural difference regarding power not only is the source of much cross-cultural misunderstanding and conflict but also significantly affects how individuals from different cultures respond to conflicts with others in high and low power.

Legitimizing Myths.

The extent to which power disparities between people and between groups are accepted in any society are embedded and constructed within a contradictory set of “legitimizing myths” about hierarchy and group superiority present in every society (Sidanius and Pratto, 1999). These myths, or systems of beliefs, tend to either support and enhance hierarchical relationships and dominant group superiority (examples are sexism, racism, classism, meritocracy, and conservatism) or challenge and attenuate these social arrangements (e.g., feminism, multiculturalism, pluralism, egalitarianism, and liberalism). These divergent sets of myths exist in a state of oppositional tension in many social systems (e.g., conservatism versus liberalism), which can provide important checks and balances against the fanaticism of either side. In some settings, these myths become infused into the “fairness-making” and “conflict-resolving” structures, thereby institutionalizing group dominance, bias, and conflict (Rapoport, 1974).

Roles.

Another powerful aspect of the structure of many social situations is the roles people assume. Role theory views power relations as if they were scripted theater. The theory holds that the roles we have in society or in our organizations (manager, laborer) often dictate the social rules or norms for our behavior. These roles establish shared expectations among members of a system, which in most cases came into existence long before the individuals who now inhabit them. It argues that we largely act out these preexisting scripts in our institutions and organizations and that these roles, these shared norms and scripts, dictate our experiences, expectations, and responses to power. So, for example, role theory argues that the CEO from our initial example was acting more or less consistently with what would be expected from someone in his position. Furthermore, if any one of his employees had been in the same position, that person would have made essentially the same decision, for it is within the underlying structure of the organization and its place in society that power relations between groups are largely predetermined and thereby constrained and perpetuated.

One of the most blatant examples of the power of roles to determine behavior is the classic experiment conducted at Stanford University on the effects of deindividuated roles on behavior in institutional settings (Haney, Banks, and Zimbardo, 1973). Student subjects were recruited for this study and randomly assigned to play the role of either a guard or a prisoner in a simulated prison environment for two weeks. From the very beginning, the “guards” abused and denigrated the “prisoners,” showing increasingly brutal, sadistic, and dehumanizing behavior over time. The research observations were so disturbing that the study was called off after only six days.

Hierarchy.

A related component of structure is hierarchy. Barnard (1946) argued that distinctions of status and authority are ultimately necessary for effective functioning and survival of any group above a certain size. As a result, most groups form some type of formal or informal hierarchical structure to function efficiently. Often the greater advantages associated with higher positions lead to competition for these scarce positions and an attempt by those in authority to maintain their status. This is consistent with the findings of social dominance theory (Sidanius and Pratto, 1999).

However, a hierarchical structure does not necessarily lead to competitive or destructive power relations within a group. In a series of studies on power and goal interdependence, Tjosvold (1997) found that variation in goal interdependence (task, reward, and outcome goals) affected the likelihood of constructive use of power between high-power and low-power persons. Cooperative goals, when compared to competitive and independent goals, were found to induce “higher expectations of assistance, more assistance, greater support, more persuasion and less coercion and more trusting and friendly attitudes” between superiors and subordinates (Tjosvold, 1997, p. 297). The abundant research on cooperative and competitive goal interdependence (see chapters 1 and 4 in this Handbook) has consistently demonstrated the contrasting effects of these goal structures on people’s attitudes and behaviors in social relations. Among other things, competition fosters “attempts to enhance the power differences between oneself and the other,” in contrast with cooperation, which fosters “an orientation toward enhancing mutual power rather than power differences” (Deutsch, 1973). In cooperative situations, people want others to perform effectively and use their joint resources to promote common objectives.

Inequitable Opportunity Structures.

At the structural level, we also see the establishment of opportunity structures that often grant the powerful unequal or exclusive access to positions of leadership, jobs, decent housing, education, health care, nutrition, and the like. Galtung (1969) labeled the effects of this “structural violence” because of its insidious and deleterious effects on marginalized communities. These inequities contribute to a setting where difficult material circumstances and political conflict lead to social disorganization, which makes it harder for some people to get their basic physical and psychological needs met. The result is a pervasive sense of powerlessness for many members of low-power groups. The privileged circumstances of the powerful, on the contrary, insulates them and contributes to their lack of attention and response to the concerns of those in low power until a crisis, such as an organized or violent act of protest, demands their attention (Deutsch, 1985). Typically, the powerful respond to such acts of protest with “prosocial” violence to quell the disturbance and maintain the status quo.

* * *

The many personal and environmental factors outlined here interact to both encourage and constrain responses to power inequality and conflict. However, because these different areas of research have often gone off in different directions, we today find ourselves with a rather fractured understanding of power and conflict dynamics. We currently have a series of midlevel or microlevel models of antecedents, processes, and outcomes that have yet to become convergent with a more general theory of social relations.

Principles of Power-Conflict Dynamics

The following set of principles is gleaned from the literature and grounded in the assumption that power differences affect conflict processes that can affect power differences:

- Significant changes in the status quo of the balance of power between parties can affect experiences of relative deprivation and increase conflict aspirations . Relative deprivation theory is a central model of the origins of conflict, which specifies the conditions under which need deprivation produces conflict (Merton and Kitt, 1950; see chapter 45 in this Handbook). Relative deprivation is said to occur when need achievement falls short of a reasonable standard determined by what one has achieved in the past, what relevant comparison others are achieving, what law or custom entitles one to, or what one expects to achieve. Research has shown that people compare themselves with others who are salient or similar to themselves in group membership, attitudes, values, or social status (Major, 1994). However, when changes in the status quo lead to a reordering of relative group status (such as through changes brought on by elections or military coups), new comparisons will be made to the previously dominant (and incomparable) groups, leading to an increase in awareness of deprivation relative to those groups (Gurr, 1970). Such changes are likely to increase demands for change by those experiencing deprivation, and thus to the open expression of conflict. This dynamic has been central to many social movements in the United States, such as the civil rights and women’s movements.

- Obvious power asymmetries contain conflict escalation, while power ambiguities foster escalation . Research suggests that situations where there exist significant imbalances of power between groups are more likely to discourage open expressions of conflict and conflict escalation than situations of relatively balanced power (Deutsch, 1973). For instance, in a historical analysis of wars between 1816 and 1989, Moul (2003) found that approximate parity in power capabilities (abilities to oppose individual states) encouraged wars between great power disputants. Sidanius and Pratto (1999) have argued that this can account for the utility and ubiquity of asymmetrical group status hierarchies worldwide. However, research in the interpersonal realm has shown that the relationship between power symmetry and destructive conflict is moderated by trust; when parties of equal power are trusting of each other, they will choose more cooperative strategies to resolve their differences (Davidson, McElwee, and Hannan, 2004).

- Sustainable resolutions to conflict require progression from unbalanced power relations between the parties to relatively balanced relations . Adam Curle (1971), a mediator working in Africa, proposed a particularly useful model for understanding the longitudinal relationships between conflict, power, and sustainable outcomes (see Lederach, 1997, for more detail). He suggested that as conflicts moved from unpeaceful to peaceful relationships, their course could be charted on a matrix that compares two elements: the level of power between the disputants and the level of awareness of the conflict. Curle described this progression toward peace as having four stages. In the first stage, conflict is hidden to some of the parties because they are unaware of the imbalances of power and injustices that affect their lives. Here, any activities or events resulting in conscientization (erasing ignorance and raising awareness of inequalities and inequities) move the conflict forward. This is where the experience of relative deprivation fits it. An increase in awareness of injustice leads to the second stage, confrontation , when demands for change from the weaker party bring the conflict to the surface. Confrontations, of course, can take many forms from cooperative to nonviolent to violent. Under some conditions, these confrontations result in the stage of negotiations , which are aimed at achieving a rebalancing of power in the relationship in order for those in low power to increase their capacities to address their basic needs. Successful negotiations can move the conflict to the final stage of sustainable peace if they lead to a restructuring of the relationship that effectively addresses the substantive and procedural concerns of those involved. Support for this model is anecdotal and could be considerably strengthened through case studies and longitudinal survey research.

-

A chronic competitive (assertive) orientation to power is often costly

. From a practical perspective, a chronic competitive approach to power has harmful consequences. Deutsch (1973) suggested that reliance on competitive and coercive strategies of influence by power holders produces alienation and resistance in those subjected to the power. This in turn limits the power holder’s

ability to use other types of power based on trust (such as normative, expert, referent, and reward power) and increases the demand for scrutiny and control of subordinates. A parent who demands obedience from his adolescent son in a climate of mutual distrust fosters more distrust and must be prepared to keep the youngster under surveillance. If the goal of the power holder is to achieve commitment from subordinates rather than merely short-term compliance, excessive reliance on a power-over strategy eventually proves to be costly as well as largely ineffective. Research by Kipnis (1976) supported this contention by demonstrating that a leader’s dependence on coercive strategies of influence has considerable costs in undermining relationships with followers and in compromising goal achievement.

Furthermore, it is evident that when power holders have a chronic competitive perspective on power, it reduces their chance to see sharing power with members of low-power groups as an opportunity to enhance their own personal or environmental power (Coleman, 2004). From this chronic competitive perspective, power sharing is typically experienced as a threat to achieving one’s goals, and the opportunities afforded by power sharing are invisible. If the father views the conflict over curfew as a win-lose power struggle, he is unlikely to reflect on the advantages of involving his daughter in reaching a solution and thereby engendering in her an improved sense of responsibility, collaboration, and trust.

- Cooperative interdependence in conflict leads to power with . When conflicts occur in situations that have cooperative task, reward, or outcome interdependence structures, or between disputants sharing a cooperative psychological orientation, there is more cooperative power. In other words, in these situations, conflict is often framed as a mutual problem to be solved by both parties, which leads to an increased tendency to minimize power differences between the disputants and to mutually enhance each other’s power in order to work together effectively to achieve their shared goals. Thus, if the parents can recognize that their daughter’s social needs and their own needs to have a close family life are positively linked, then they may be more likely to involve her in the problem-solving and decision-making processes, thereby enhancing her power and their ability to find mutually satisfying solutions to the conflict.

-

The overwhelming evidence seems to indicate that the powerful tend to like power, use it, justify having it, and attempt to keep it

. The powerful tend to be more satisfied and less personally discontent than those not enjoying high power; they have a longer time perspective and more freedom to act and therefore can plan further into the future. These higher levels of satisfaction lead to vested interests in the status quo and development of rationales for maintaining power, such as the power holders’ belief in their own superior

competence and superior moral value (Deutsch, 1973). Kipnis (1976) argued that much of this may be the result of the corrupting nature of power itself. He proposed that having power and exercising it successfully over time lead to an acquired “taste for power,” inflated sense of self, devaluing of those of lesser power, and temptation to use power illegally to enhance one’s position.

Fiske (1993) has demonstrated that powerful people tend to pay less attention to those in low power since they view them as not affecting their outcomes, they are often too busy to pay attention, and they are often motivated by their own high need to dominate others. Inattention to the powerless makes powerful people more vulnerable to use of stereotypes and implicit theories when interacting with the powerless. Mindell (1995) explained the state of unawareness that having privilege often fosters in this way: “Rank is a drug. The more you have, the less aware you are of how it affects others negatively” (p. 56).

Thus, in conflict situations high-power holders and members of high-power groups (HPGs) often neglect to analyze—as well as underestimate—the power of low-power holders and members of low-power groups (LPGs; Salacuse, 2001). In addition, they usually attempt to dominate the relationship, use pressure tactics, offer few concessions, have high aspirations, and use contentious tactics. HPGs therefore make it difficult to arrive at negotiated agreements that are satisfactory to all parties.

When members of HPGs face a substantial challenge to their power from LPGs, their common responses fall into the categories of repression or ambivalent tolerance (Duckitt, 1992). If the validity of the concerns of the LPG is not recognized, HPGs are likely to use force to quell the challenge of the LPG. But if the challenges are acknowledged as legitimate, HPGs may respond with tolerant attitudes and expressions of concern—though ultimately with resistance to implementing any real change in their power relations (Duckitt, 1992). This has been termed the attitude-implementation gap .

In light of their unreflective tendency to dominate, it becomes critical for members of HPGs to be aware of the likelihood that they will elicit resistance and alienation (from members of LPGs with whom they are in conflict) through using illegitimate techniques, inappropriate sanctions, or influence that is considered excessive for the situation (Deutsch, 1973). The cost to the HPG is not only ill will but also the need to be continuously vigilant and mobilized to prevent retaliation by the LPG.

-

The tendencies for members of LPGs are opposite to those of members of HPGs, with one important exception: LPG members tend to be dependent on others, have short time perspectives, are unable to plan far ahead, and are generally discontent

. Often the LPG members attempt to rid themselves of the negative feelings associated with their experiences of powerlessness and dependence (such as rage and fear) by projecting blame onto even less powerful groups or onto relatively

safe in-group targets. The latter can result in a breakdown of LPG in-group solidarity (Kanter, 1977), and impair their capacities for group mobilization in conflict. Intense negative feelings may also limit the LPG members’ capacity to respond constructively in conflict with HPGs and impel such destructive impulses as violent destruction of property (Deutsch, 1973).

Several tactics can enhance the power of LPGs. The first is for the group to amass more power for assertion—either by increasing their own resources, organization, cohesion, and motivation for change or by decreasing the resources of (or increasing the costs for) the HPGs (see chapter 2 in this Handbook). The latter can be accomplished through acts of civil disobedience, militancy, or what Alinsky (1971) described as “jujitsu tactics”: using the imbalance of power in the relationship against the more powerful. Another approach available to LPG members is to attempt to appeal to the better side of the members of the HPG by trying to induce them (through such tactics as ingratiation, guilt, and helplessness) to use their power more benevolently or by trying to raise HPG awareness of any injustice that they may be party to. LPGs would also do well to develop a broad menu of tactics and skills in implementing the strategies of autonomy, dependence, and community.

* * *

Despite many decades of fine research, our field still lacks a basic unifying framework that integrates our understanding of the many theories and principles of power and conflict dynamics. Thus, the findings from this research are often piecemeal, decontextualized, contradictory, or focused solely on negative outcomes. I next describe a new model of power and conflict that aims to bring a sense of coherence and parsimony to the study of power and conflict.

A SITUATED MODEL OF POWER AND CONFLICT

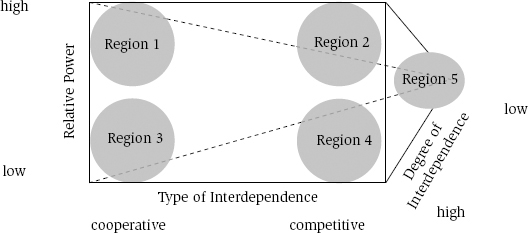

Our model builds on Deutsch’s theory of social relations and psychological orientations (Deutsch 1982, 1985, 2007, 2011) to offer a situated model of power and conflict (Coleman, Kugler, Mitchinson, Chung, and Musallam, 2010; Coleman, Vallacher, and Nowak, 2012; Coleman, Mitchinson, and Kugler, 2009; see figure 6.1 ). It suggests that when people are faced with a conflict, they have three primary considerations:

Figure 6.1 The Situated Model of Power and Conflict

- Is the other party with me or against me or some combination of both?

- What is my power relative to the other party’s (high, equal or low)?

- To what extent are my goals linked to the other party’s goals, and how important is this conflict and relationship to me?

The model specifies the three basic dimensions of conflict situations:

- The mixture of goal interdependence : The type and mix of goal interdependence in the relationship, with pure positive forms of goal interdependence (all goals between parties in conflict are positively linked) at the extreme left of the x -axis, pure negative interdependence (all goals are negatively linked) at the extreme right of the x -axis, and mixed-motive types (combinations of both positively and negatively linked goals) along the middle of the x -axis.

- The relative distribution of power : The relative degree to which each party can affect the other party’s goals and outcomes (Depret and Fiske, 1993; Thibaut and Kelley, 1959). It constitutes the y -axis of the model, with pure types of unequal distribution of power (A over B) at the top of the y -axis, the opposite types of unequal distribution of power (B over A) at the bottom of the axis, and various types of relatively equal distribution of power along the middle of the y -axis.

- The degree of total goal interdependence–relational importance : The degree of importance of the relationship and linkage of goals (total goal interdependence) in conflict. This constitutes the z -axis of the model, with high degrees of goal interdependence between the parties in conflict located at the front of the z -axis (strong goal linkages and/or high proportions of linked goals), low degrees of interdependence located at the rear of the z -axis (no, few, or weak goal linkages), and moderate degrees of goal interdependence located along the middle of the z -axis.

These three dimensions constitute the core of the situated model. They provide a sense of the basic social context in which people experience conflict. Thus, conflicts that appear to be similar by virtue of representing the same perception of incompatible activities (you and I are competing for the same job) may be experienced in fundamentally different ways depending on the settings of the three parameters in the model (our mix of cooperative or competitive goals; my high, equal, or low relative power; and the high or low importance of our relationship).

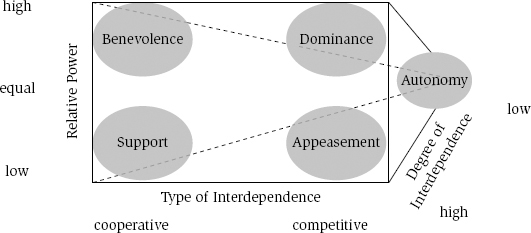

The situated model suggests that when conflicts are perceived, the three basic features of social conflict—mix of interdependence, relative distribution of power, and degree of total interdependence—interact to situate parties psychologically in different regions of a conflict stimulus field (Kelley 1997): a perceiver’s representation of his or her external world or environment. These different regions tend to afford distinct conflict orientations, which are syndromes of disputants’ perceptions, emotions, values, and behaviors in the conflict (see figure 6.2 ). In other words, the different regions of the stimulus field tend to influence how conflicts are perceived (as mutual problems or win-lose challenges), how it feels to be in the situation (relatively comfortable versus anxiety provoking), what is likely to be valued in the situation (solving problems and sharing benefits with other parties versus conquering them), and how to best go about responding to the conflict and obtaining these values and goals (through respectful dialogue and problem solving versus forceful domination or submission to power). The different regions do not rigidly determine specific thoughts, feelings, and actions in conflict but rather tend to orient disputants like improvisational scripts; they provide the general frame and contours for responses to conflict, and mostly determine which behaviors are not appropriate to a particular situation.

Figure 6.2 Psychological Orientations in the Basic Conflict Stimulus Field

The findings from research conducted through focus groups, critical incidents, and correlational and experimental studies have found that when participants were presented with the same conflict in terms of incompatible goals and issues, they described markedly different experiences—perceptions, emotions, values, and behavioral intentions—across the five regional conditions (Coleman et al. 2010; Coleman, Kugler, Mitchinson, and Foster, 2013). When faced with a region 1 scenario (relative high-power, cooperative, high-interdependence relations), participants described a more benevolent orientation to conflict than most other regions. Participants said they valued taking responsibility for the problem and listening to the other, and they expressed genuine concern for their low-power counterpart. In contrast, region 2 scenarios (relative high power, competitive, high interdependence) were found to induce an angrier, more threatening, and confrontational approach to the other party, with heightened concerns for their own authority and goals (dominance). Region 3 scenarios (low power, cooperative, high interdependence) afforded more of an orientation of appreciative support than the other regions, where people respectfully sought clarification of roles and responsibilities, worked harder, and felt anxious and confused about the conflict situations. This was in contrast to the reactions observed to region 4 scenarios (low power, competitive, high interdependence), which induced higher levels of stress and anger, a strong need to tolerate the situation, and a desire to look for possibilities to sabotage the supervisor if the opportunity presented itself (appeasement). Region 5 scenarios (low interdependence), in contrast to the others, afforded a less intense experience of the conflict, where people preferred to simply move on or exit the conflict (autonomy).

When parties perceive themselves to be located in a particular region of the stimulus field for extended periods of time (e.g., stuck in low power in a competitive conflict with their boss), they will tend to foster the development of a stronger orientation for that region, which can become chronic. Once an individual has developed a strong propensity for a particular conflict orientation (e.g., dominance), it can become very difficult to change one’s orientation, even when it fails to satisfy one’s goals, the intensity of the conflict dissipates, or social conditions change (see Coleman et al., 2010). More chronic orientations will often operate with automaticity and may begin to be employed even when they are inconsistent (ill fitting) with particular situations (Barge, 1996). For example, case study research on state-level international negotiations also provides strong support for the view that high-power parties often become very comfortable with dominance orientations and find it difficult to employ other strategies when power shifts and conditions change, and that low-power parties too can become very skilled and accustomed to their role (Zartman and Rubin, 2002).

Generally, more adaptive orientations to conflict—those that allow the use of different orientations and behaviors in order to satisfy goals in a manner not incongruent with the demands of the situations encountered—will lead to greater general satisfaction with conflict processes and outcomes over time. It is important to stress that each of the different orientations outlined in our model has its particular utilities, benefits, costs, and consequences depending on the psychological makeup of people, the orientation of other parties, and the nature of the situations. Ultimately what is particularly useful in evolving situations of conflict is the capacity to adapt: to move freely between various orientations and employ their related strategies and tactics in a manner that helps to achieve one’s short- and long-term goals.

Case-based research on interstate negotiations found that parties tended to be more effective in negotiations to the extent that they were able to adjust their orientations and behavior to the relative (and relevant) power of the other side (Zartman and Rubin, 2002). In a correlational study (Coleman et al., 2009), investigators found that more adaptive individuals (those who saw utility in employing all five orientations when necessary) had greater levels of satisfaction with conflicts in general than did less adaptive individuals. This study also found that more adaptive individuals learned more from conflicts and had more global perspectives on conflict, focusing more on both long-term and short-term goals than less-adaptive individuals did. Another study found that people who were able to employ orientations and behaviors that were not incongruent with the situation (ill fitting) expressed significantly more satisfaction with the processes, outcomes, relationships, and their own behavior in those conflicts (Coleman and Kugler, 2011).

The situated model of power and conflict builds on the essential features of social conflict that have been identified by prior research and theorizes how different configurations of these factors together influence constructive and destructive dynamics in conflict. By integrating the three dimensions, the model helps to synthesize many disparate and even contradictory findings from decades of prior research and therefore contribute to our understanding of how power, interdependence, and relational importance affect conflict dynamics. Instead of emphasizing how a set of predispositions or conditions invokes positive conflict processes, the model stresses the necessity of adapting flexibly to new situations in a manner that helps to achieve important goals. Conflicts can be constructively managed when the disputants are able to move between different orientations, strategies, and tactics as the evolving situation requires.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TRAINING IN CONFLICT RESOLUTION

The situated model of power and conflict presented here highlights the importance of adaptivity in constructive conflict resolution. This is what Harvard professor Joseph Nye (1990) has called smart power—a capacity to combine the use of hard power (military, economic) and soft power (moral, cultural) as circumstances dictate. Research has found that although many negotiators and leaders tend to get stuck in one approach to negotiating conflict (often domination), more effective leaders and negotiators are more nimble (Hooijberg and Quinn, 1992; Lawrence, Lenk, and Quinn, 2009; Zartman and Rubin, 2002). They read situations more carefully, consider their short- and longer-term objectives, and then employ a variety of strategies in order to increase the probabilities that their agenda will succeed (Dörner, 1996).

Thus, according to our model, conflict resolvers of all stripes should develop their capacities and skills for these traits:

- Domination through command and control—employing power, information, and authority to demand, incentivize, threaten, coerce, expose and, publicly shame opponents when absolutely necessary

- Taking the high road through benevolence—modeling exemplary, collaborative, win-win leadership by listening carefully to the needs and concerns of opponents, finding common ground on the priority objectives, and uniting parties around a common vision and purpose

- Building bottom-up support—reaching out to the other side, allies, and other stakeholders in order to persuade, seduce, barter, beg, and ingratiate in order to mobilize them and secure their support

- Appeasing opponents—learning to tolerate attacks, inflammatory rhetoric, and hyperbole of opponents in the short-term; give in to them on their key demands; suck up to them as much as possible, and quietly lay in wait for conditions to change and opportunities to present themselves to blithely sabotage them and derail their agenda

- Developing autonomy through strong BATNAs (best alternative to a negotiated agreement)—spending time and energy developing a good plan B, where they can still achieve their principle goals unilaterally

Our upcoming book, Conflict Intelligence: Harnessing the Power of Conflict and Influence (Coleman and Ferguson, in press), provides step-by-step instructions for developing skill in applying these strategies and tactics and enhancing competencies for adaptivity in conflict.

In conclusion, I offer a few summary propositions from this chapter for use in designing training approaches for power and conflict. The general goals of such training are to develop people’s understanding of power, facilitate reflection of their own tendencies when in low or high power, and increase their ability to use it effectively when in conflict:

- Training should help students understand and reflect critically on their commonly held assumptions about power, as well as the sources of these assumptions. It should also educate students on the dynamic complexity of processes of power and influence; the importance of localized, situation-specific understanding; and the importance of distinctions such as primary and secondary power.

- Students should be supported in a process that helps them become aware of their own chronic tendencies to react in situations in which they have superior or inferior power over others and develop the capacity to employ dominance, benevolence, appeasement, support, and autonomy when necessary and appropriate.

- Students should be encouraged to become more emotionally and cognitively aware of the privileges or injustices they and others experience as a result of their skin color, gender, economics, class, age, religion, sexual orientation, physical status, and the like.

- In a conflict situation, students should be able to analyze for the other as well as themselves the resources of power, their orientation to power, and the strategies and tactics for effectively implementing their available power. Students should also be able to identify and develop the necessary skills for implementing their available power in the conflict.

- Students should be able to distinguish between conflicts in which power with, power from, and power under, rather than power over, are appropriate orientations to and strategies for resolving the conflict.

Susan Fountain has developed an exercise showing the type of training that gives students simple yet rich experience useful for exploring and examining many of the principles I have just described.

Participants in the exercise are asked to leave the training room momentarily. The room is then organized into two work areas, with several tables grouped to accommodate four or five people per group in each area. In one work area, the tables are supplied with markers, colored pencils, paste, poster board, magazines, scissors, and other colorful and decorative items. In the other work area, each table receives one piece of white typing paper and two black lead pencils. The participants are then randomly assigned to two groups and allowed into the room and seated.

The groups are told that their objective is to use the materials they have been given to generate a definition of power. They are informed that once each group has completed its task, they will display their definition and everyone will vote on the best definition generated from the class. The groups begin their work on the task. The trainers actively support and participate in the work of the high-resource group while attempting to avoid contact with members of the low-resource group. When the work is complete, the class votes on the best definition of power. The participants are then brought into a circle to debrief.

In our experience with this exercise, many useful learning opportunities present themselves. For example, the types of definition generated can differ greatly between the high-resource and low-resource groups. The former tend to produce definitions that are mostly positive, superficial, and largely shaped by the mainstream images from the magazines (beauty, status, wealth, computers, and so on). The low-resource group definitions tend to be more radical and rageful, often challenging the status quo—and even the authority of the instructors. One image listed a series of negative emotions and obscenities circled by pencils that were then jabbed into the paper like daggers. These starkly contrasting definitions often lead to discussion that identifies the source of these differences.

It is also fairly common in this exercise for many members of the high-resource group to remain completely unaware of the disparity in resources until it is explicitly pointed out to them at the conclusion of the exercise. Members of the low-resource groups, in contrast, are all very aware of the discrepancies. This can be a very powerful moment. Again, the actual difference in resources is minor, but it is symbolic of more meaningful ones, and the participants begin to make the connection to other areas in their lives where they are often blind to their own privilege.

Finally, during the exercise, members of the low-resource group often attempt to alter the imbalance of power. They try various strategies, including demanding or stealing resources, ingratiation, playing on the guilt of high-resource group members, appealing to higher authorities (the instructors), or challenging the legitimacy of the exercise. Of course, there are also members of the low-resource group who simply accept their lot and follow the rules. These choices are all opportunities to explore what sort of strategies and tactics can be useful when in low power, have participants reflect on their own inclinations and reactions in the situation (whether in low or high power), and examine the beliefs and assumptions on which many of the strategies were based.

CONCLUSION

Rosabeth Kanter once said that power is the last dirty word. I have attempted to challenge that notion in this chapter and emphasize the potential for an expansive approach to power in conflict. The realists of the day may remain skeptical, for the world is filled with evidence to the contrary: evidence of coercive power holders, power hoarding, of the defensiveness and resistance of the powerful under conditions that cry out for change. Perhaps the time is ripe for a new approach to power.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkl-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality . New York: HarperCollins.

Alinsky, S. D. (1971). Rules for radicals: A practical primer for realistic radicals . New York: Random House.

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2 , 21–41.

Barge, J. A. (1996). Automaticity in social psychology. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles . New York: Guilford Press.

Barnard, C. I. (1946). Functions and pathology of status systems in formal organizations. In W. F. Whyte (ed.), Industry and society . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bhowon, U. (2003). Personal attributes, bases of power, and interpersonal conflict handling styles. Psychological Studies, 48 , 13–21.

Blalock, H. M. (1989). Power and conflict: Toward a general theory . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Boulding, K. E. (1990). Three faces of power . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cartwright, D. (1959). A theoretical conception of power. In D. Cartwright (ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 183–220). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute of Social Research.

Cartwright, D. (1965). Influence, leadership and control. In J. G. March (ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 1–47). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Chomsky, N. (2002). Understanding power: The indispensable Chomsky . New York: New York Press.

Clegg, S. (1989). Frameworks of power . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Coleman, P. T. (2004). Implicit theories of organizational power and priming effects on managerial power sharing decisions: An experimental study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34 , 297–321.

Coleman, P. T. (2006). Conflict, complexity, and change: A metaframework for engaging with protracted, intractable conflict—III. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 12 , 325–348.

Coleman, P. T., & Ferguson, R. (in press). Conflict intelligence: Harnessing the power of conflict and influence . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K., Mitchinson, A., Chung, C., & Musallam, N. (2010). The view from above and below: The effects of power and interdependence asymmetries on conflict dynamics and outcomes in organizations. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 3 , 283–311.

Coleman, P. T., & Kugler, K. G. (2011). Tracking adaptivity: Developing a measure to assess adaptive conflict orientations in organizations . Poster presented at the 24th Conference of the International Association for Conflict Management, Istanbul, Turkey.

Coleman, P. T., Kugler, K., Mitchinson, A., & Foster, C. (2013). Navigating conflict and power at work: The effects of power and interdependence asymmetries on conflict in organizations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43 (10), 1963–1983.

Coleman, P. T., Mitchinson, A., & Kugler, K. G. (2009). Adaptation, integration, and learning: The three legs of the steady stool of conflict resolution in asymmetrical power relations . Poster presented at the 22nd Conference of the International Association for Conflict Management, Kyoto, Japan.

Coleman, P. T., Vallacher, R., & Nowak, A. (2012). Tackling the great debate: Nature-nurture, consistency, and the basic dimensions of social relations. In P. T. Coleman (ed.), Conflict, cooperation and justice: The intellectual legacy of Morton Deutsch . New York: Springer.

Coleman, P. T., & Voronov, M. (2003). Power in groups and organizations. In M. West, D. Tjosvold, & K. G. Smith (eds.) The international handbook of organizational teamwork and cooperative working (pp. 229–254). New York: Wiley.

Curle, A. (1971). Making peace . London: Tavistock.

Dahl, R. A. (1957). The concept of power. Behavioral Science, 2 , 201–215.

Dahl, R. A. (1968). Power. In D. L. Sills (ed.), International encyclopedia of the social sciences (vol. 12). Old Tappan, NJ: Macmillan.

Davidson, J. A., McElwee, G., & Hannan, G. (2004). Trust and power as determinants of conflict resolution strategy and outcome satisfaction. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 10 , 275–292.

Depret, E. F., & Fiske, S. T. (1993). Perceiving the powerful: Intriguing individuals versus threatening groups . Unpublished manuscript, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict: Constructive and destructive processes . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Deutsch, M. (1982). Interdependence and psychological orientation. In V. Derlega & J. L. Grzelak (eds.), Cooperation and helping behavior: Theories and research . Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Deutsch, M. (1985). Distributive justice: A social psychological perspective . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Deutsch, M. (2004, February). Oppression and conflict . Paper presented at the ICCCR Working Conference on Interrupting Oppression and Sustaining Justice. Retrieved from http://www.tc.columbia.edu/icccr/IOSJ%20Papers/Deutsch_IOSJPaper.pdf

Deutsch, M. (2007). Two important but neglected ideas for social psychology as they relate to social justice . Paper presented at the Conference on Social Justice, New York.

Deutsch, M. (2011). A theory of cooperation and competition and beyond. In A. E. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (eds.), Theory in social psychology . London: Sage.

Dörner, D. (1996). The logic of failure: Why things go wrong and what we can do to make them right . New York: Holt.

Duckitt, J. H. (1992). The social psychology of prejudice . New York: Praeger.

Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review. 27 , 31–41.

Fisher, R. J., Ury, W., & Patton, B. (1991). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in (2nd ed.). New York: Penguin.

Fiske, S. T. (1993). Controlling other people: The impact of power on stereotyping. American Psychologist, 48 , 621–628.

Fiske, S. T., & Berdahl, J. L. (2007). Social power. In A. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (eds.), Social psychology: A handbook of basic principles (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Follett, M. P. (1973). Power. In E. M. Fox & L. Urwick (eds.), Dynamic administration: The collected papers of Mary Parker Follett . London: Pitman. (Original work published 1924.)

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge . New York: Pantheon.

Foucault, M. (1984). Nietzsche, history, genealogy. In P. Rabinow (ed.), The Foucault reader . New York: Pantheon Books.

French, J.R.P., Jr., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Galinsky, A. D., Magee, J. C., Gruenfeld, D. H., Whitson, J. A., & Liljenquist, K. A. (2008). Power reduces the press of the situation: Implications for creativity, conformity, and dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95 , 1450–1466.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 3 , 176–191.

Gurr, T. R. (1970). Why men rebel . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Haney, C., Banks, C., & Zimbardo, P. (1973). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International Journal of Criminology and Penology, 1 , 69–97.

Harvey, J. B. (1989). Some thoughts about organizational backstabbing. Academy of Management Executive, 3 , 271–277.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hooijberg, R., & Quinn, R. E. (1992). Behavioral complexity and the development of effective managers. In R. L. Phillips & J. G. Hunt (eds.), Strategic management: A multiorganizational-level perspective . Westport, CT: Quorum.

Kanter, R. M. (1977). Men and women of the corporation . New York: Basic Books.