CHAPTER NINE

THE PSDM MODEL

Integrating Problem Solving and Decision Making in Conflict Resolution

Eben A. Weitzman

Patricia Flynn Weitzman

One way to think about what people do when they resolve conflict is that they solve a problem together. Another way to think about it is that they make a decision—again, together. Sometimes problem solving and decision making are treated as synonymous. For convenience, we distinguish between the two in order to make clearer the ways in which they complement each other, even though the processes are intermingled in the course of conflict resolution. In the “Problem Solving” section of this chapter, we discuss diagnosis of the conflict and also the development of alternative possibilities for resolving a conflict. In “Decision Making,” we consider a range of the kinds of decisions people involved in resolving conflict have to make, both individually and together, including choice among the alternative possibilities and commitment to the choice that is made. When faced with the necessity for commitment and choice, the parties may decide that the alternatives are inadequate and reiterate the process of diagnosis and development of alternatives (problem solving); there may be repeated cycles of such reiteration before a conflict is resolved. This implies a cooperative conflict resolution process consisting of four general phases: (1) diagnosing the conflict, (2) identifying alternative solutions, (3) evaluating and choosing a mutually acceptable solution, and (4) committing to the decision and implementing it. As we discuss in this chapter, this process is not strictly linear, and it will often be necessary to loop back through parts of it repeatedly.

It is thus possible to think about problem solving and decision making as components of a broader conflict resolution process. Research and practice over the past few decades have shown these ways of thinking about conflict to be profitable for both understanding conflict and developing constructive approaches to resolving it. We begin by suggesting a simple model of the interaction between problem-solving and decision-making processes in conflict resolution. This model introduces a framework and guide for the remainder of the chapter.

A SIMPLE MODEL

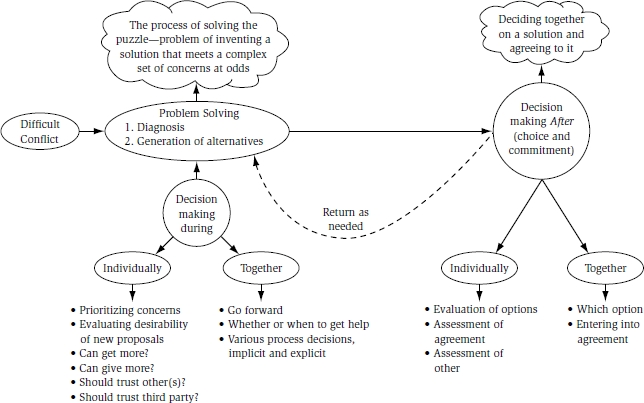

In figure 9.1 , we suggest an integrated model of problem solving and decision making in conflict resolution. (For simplicity, we refer to it as the PSDM model .) When people are unable to resolve conflict constructively, they are in some way unable or unwilling to reach a resolution that is to all parties—at the least—acceptable. There are many potential sources of such stuckness. Their interests might appear to be (or actually be) incompatible; they might be too angry with one another to talk constructively; they might have fundamental differences in values about the subject of their conflict or about processes for resolving it; they may hold different versions of “the truth” about what has already happened, what will happen, or about any of the “facts” involved; they may have different views of, or desires for, the nature of their relationship, or they may have deep misunderstandings that are hard to sort out. (Because the word interests is often understood as a reference to the tangible outcomes people may be seeking, we use the term concerns to encompass not only interests but also values, emotional investments, views of reality, and so on.)

Figure 9.1 An Integrated Model of Problem Solving and Decision Making in Conflict Resolution

We could say, then, that there is a complex puzzle, or problem, to be solved: putting together the various interests, values, preferences, realities, emotional investments, and so on, of the parties involved and finding a solution that accounts for these at least well enough. In that sense, problem solving needs to take place. Along the way, there are many decisions to be made, both individually and together (see figure 9.1 ). The private decisions include prioritizing concerns, evaluating proposals, figuring out whether to offer or seek more, and deciding whether to trust, to name a few. Decisions to be made together may concern processes to be used, whether and when to get help from a third party, choices from among the options generated during problem solving, and whether to enter into an agreement. Some of these decisions are made during the course of problem solving and some after the problem-solving process has yielded a set of alternatives to consider. One possible decision to be made afterward is whether the options generated are adequate or inadequate. If inadequate, the parties must return to another round of problem solving. So, the process may be iterative, necessitating repeated return to the problem-solving stage until the parties decide to agree.

The rest of this chapter aims to move us through this outlined process. To do so, we must understand the parts of the process, and how they work.

Note that in what follows, the lists of decisions to be made are intended to be illustrative, not exhaustive.

PROBLEM SOLVING

Broadly speaking, problem-solving approaches to understanding and resolving conflict deal with conflict as a puzzle, or interpersonal dilemma, to be worked out. There are two fundamental parts to the problem-solving process:

- Diagnosing the conflict (figuring out what the cause of the stuckness is, or identifying the problem)

- Developing alternative solutions to the problem

In this section, we give an overview of some problem-solving approaches to conflict resolution. We discuss some of the research that supports the use of problem-solving approaches, as well as research that helps us understand the conditions under which problem solving is more or less likely to be undertaken. We also consider some of the major critiques of problem-solving approaches, both in the literature and out in the field.

Problem Solving as the Search for Good, Constructive, Mutually Satisfying Solutions

An important part of the motivation to engage in problem solving is a desire to take some of the heat out of the process—to move people away from being stuck in their anger, their desire for revenge, and so on, and focus them on finding a way out.

One view of how problem-solving approaches attempt to do this has to do with a particular understanding of what the word problem means. One sense of the word is as dilemma, obstacle, difficulty, or predicament—generally, a bad thing. Another is as puzzle, enigma, riddle, or question—often seen as a challenge and even an opportunity for growth. Conflicts are often felt to be problems in the first sense of the word: as difficulties or predicaments. Problem-solving approaches to conflict resolution attempt to recast the conflict as a problem in the second sense—as puzzles or riddles—and attempt to engage the parties in solving those puzzles. In a training or intervention, we might hear the notion put something like this: “We’re in conflict. We can fight it out, or work it out. If we’re going to work it out, let’s figure out what that would take.” (See chapters 1 and 30 in this Handbook for further discussion of reframing a conflict as a mutual problem to be solved cooperatively.)

Along these lines, Rubin, Pruitt, and Kim suggest that “problem solving can be defined as any effort to develop a mutually acceptable solution to a conflict” (1994, p. 168; emphasis added). Developing mutually acceptable solutions is the hallmark of problem-solving approaches.

A Discussion of Problem-Solving Approaches.

In the third edition of their book Social Conflict , Pruitt and Kim (2004) (earlier editions were coauthored with the late Jeffrey Rubin) offer one of the best, most useful discussions available of problem-solving approaches. So it seems worthwhile to devote a few paragraphs to their work at the outset of this chapter.

Although the phrase “any effort” in the preceding quote might leave the definition a bit broad, those authors go on to clarify the highest aspirations of problem-solving approaches:

At its best, problem solving involves a joint effort to find a mutually acceptable solution. The parties or their representatives talk freely to one another. They exchange information about their interests and priorities, work together to identify the true issues dividing them, brainstorm in search of alternatives that bridge their opposing interests, and collectively evaluate those alternatives from the viewpoint of their mutual welfare. (Pruitt and Kim, 2004, p. 190)

In describing problem-solving approaches, the same authors describe two broad classes of outcomes that can be sought: compromise (meeting in the middle through a process of sacrifice on both sides) and integrative solutions (those in which all parties’ needs are considered and met).

The second type of solution, the integrative, is the hoped-for goal in problem-solving approaches, though it may not always be realistically possible (more on this later). Pruitt and Kim (2004) review a variety of forms for finding such solutions:

- Expanding the pie (finding ways to work together to create more of a resource to be divided)

- Nonspecific compensation (finding new ways to compensate a party for yielding on an issue)

- Cost cutting (finding ways to reduce the cost for a party in yielding on an issue)

- Logrolling (each side concedes on issues it believes are less important, building momentum toward agreement and goodwill)

- Bridging (new options are created that satisfy critical underlying interests, if not the initial demands that were put on the table)

To illustrate, imagine the case of a hypothetical labor negotiation in which management and a union are divided over a range of issues, including wages, medical insurance, disability, workplace safety conditions, and productivity goals. The first approach, expanding the pie, might entail raising prices to bring in more revenue to support the compensation desired by the union, while also providing more profit for the company. The second, nonspecific compensation, might oblige management to offer, say, additional vacation time or a flex-time arrangement to compensate for a concession on wage demands. Cost cutting might involve finding a new insurance company that is able to provide better benefits without costing the company as much as the old plan would have charged. The parties might also engage in the fourth approach, logrolling: the union concedes on a minor change in productivity goals (which union representatives view as less important in this case), and management concedes on an issue of work safety conditions that is relatively inexpensive to fix.

The combination of agreements builds momentum toward reaching agreement on some of the more difficult issues. Finally, the parties might find a bridging solution, in which moderate redesign of the facility and work flow (1) eliminates the safety issue (union interest) and (2) increases productivity (management interest) without imposing an unacceptable burden on the workers, (3) thereby generating the revenue to pay for increased wages and benefits (union interest) as well as profits (management interest). What makes this bridging solution different from the price-raising, expanding-the-pie example is that it makes use of a new option (redesign) that addresses the various underlying interests on both sides of the table in an integrative way.

A key component, not only to the approach Pruitt and Kim described, but to most of the problem-solving approaches, is analyzing underlying interests—those often unspoken real needs that produce the publicly stated demands in the first place. In addition, Pruitt and Kim suggest pushing further to look for interests under those interests, and so on, in an effort to find interests that are bridgeable—that is, satisfiable in newly created, mutually acceptable ways.

Pruitt and Kim (2004) offer a good description of a problem-solving process for conflicts of interest. They suggest (1) determining whether there is a real conflict of interest; (2) determining one’s own interests, setting high aspirations, and sticking to them; and (3) seeking a way to reconcile both parties’ aspirations. Note that steps 1 and 2 are part of the diagnosis phase of problem solving, and step 3 represents the phase of generating alternatives. If step 3 is particularly difficult, it may be necessary to lower aspirations and search some more. Steps 2 and 3 represent the core of many problem-solving approaches: developing clarity as to the real issues and interests and developing mutually satisfactory solutions.

Evidence of Better Outcomes with Problem-Solving Approaches.

There is evidence for the effectiveness of problem-solving approaches in both the short term (reaching agreements, short-term satisfaction) and the long term (long-term satisfaction with, adherence to, and quality of agreements).

In a key study, Kressel and his colleagues (1994) compared the effectiveness of mediators using a problem-solving style (PSS), focused on good problem solving rather than settlement itself, with those using a settlement-oriented style (SOS), focused on the goal of getting an agreement, “more or less independent of the quality of the agreements” (p. 73), in child custody cases. They found overwhelmingly that disputants working with mediators using PSS more frequently reached settlement and were more satisfied with their agreements. They also found that the PSS settlements tended to be more durable, produce long-term outcomes of higher quality, leave disputants with more favorable attitudes toward the mediation, and be more likely to have a lasting positive impact on the relationship between parties. It is also important to note that there were some consistent exceptions: for example, when one party bargained in bad faith or was psychologically disturbed, PSS did not produce workable agreements.

Although Kressel and colleagues focused on long-term outcomes, Zubek and her colleagues (1992) looked at short-term benefits of problem-solving behavior in mediation in community mediation centers. They demonstrated a greater likelihood of short-term success in mediation (STSM) with joint problem solving and less STSM with hostile and contending behavior by the conflicting parties. They then looked at the mediator behaviors that led to STSM and found them to include those that stimulate thinking and structure discussion. In addition, the more that mediators applied pressure on disputants to reach agreement, the lower the rates were of reaching agreement and goal achievement, satisfaction with the agreement, and satisfaction with the conduct of the hearing, which lends further support for the PSS versus SOS findings of Kressel and colleagues.

In yet another context, van de Vliert, Euwema, and Huismans (1995) found that problem solving tended to enhance effectiveness in conflict for police sergeants, with both superiors and subordinates. This is the type of traditional, hierarchical context many critics point to as one in which a problem-solving approach is unlikely to gain acceptance or be effective. Furthermore, it is worth noting that problem solving tended to enhance the sergeants’ effectiveness in conflicts with both their subordinates and their superiors (though the latter effect represented a nonsignificant trend).

Finally, Carnevale and Pruitt (1992) reviewed a wide range of both experimental and field research on problem solving in negotiation and mediation. They concluded that problem solving is much more likely than other approaches to lead to win-win solutions to conflicts. In addition, they found that problem solving is more likely both to be engaged in and to be effective, when disputants are concerned about the other party’s welfare than when they are focused solely on their own.

Research That Predicts Use of Problem Solving.

Given the potential benefits of problem-solving approaches, it is helpful to know about the conditions under which disputants are more or less likely to engage in problem-solving behavior.

Some information is available. Strutton, Pelton, and Lumpkin (1993) found that if the psychological climate of an organization was characterized by higher levels of (1) cohesion, (2) fairness, (3) recognition of success, and (4) openness to innovation, members were more likely to choose problem-solving and persuasion strategies and less likely to engage in bargaining and politicking. In a study pointing to factors that might inhibit problem solving, Dant and Schul (1992) found that a group making frequent use of integrative problem-solving conflict resolution strategies among its members still preferred directive third-party intervention when stakes were high, issues were complex, there were significant policy implications, and dependence on the organization was high.

Carnevale and Pruitt (1992), as well as Pruitt and Rubin (1986), argue that disputants’ relative levels of concern for their own and each other’s interests predict the conflict resolution strategy that is adopted. Thus, when disputants do not care about their own or the other’s outcomes, they are likely to adopt a strategy of inaction; when they are concerned with the other’s outcome but not their own, they are likely to yield; and when they are primarily concerned about their own interests, they tend to adopt contending strategies. But when disputants are concerned about both their own interests and the other’s as well (holding a dual concern ), they are more likely to engage in problem solving. This suggests that strategies and techniques that help to cultivate a concern for the other’s interests and outcomes help to promote problem solving in conflict situations. (See also chapter 1, the “Initiating Cooperation and Competition” section.)

Individual and Social Interaction Perspectives on Problem Solving

Consistent with the viewpoint put forth by Carnevale and Pruitt (1992), another angle on problem solving in conflict has come from the social cognitive literature, particularly from developmental researchers interested in the development of social understanding and its relationship to thought processes during conflict and other social interactions. Within cognitive psychology, problem solving is viewed as a cognitive process, very much in the sense of working through puzzles (solving a math problem, stacking crates to get the banana, and so on). Social cognition theorists have tended to look at conflict resolution as a particular kind of cognitive problem solving, that of solving interpersonal problems.

Two complementary ways of looking at interpersonal conflict have arisen from this perspective. One takes an information-processing approach, in which each phase of the interpersonal problem-solving process is analyzed against an ideal standard (for example, Dodge, 1980; Spivack and Shure, 1976). The individual goes through an internal problem-solving process in determining how to engage with the other. More effective strategies are equated with success at achieving some predetermined outcome. The phases are (1) identifying the problem, (2) generating alternative strategies, (3) evaluating consequences, and (4) using new or different strategies for resolution. It is important to note that these phases may be executed well or poorly and may lead to a decision to engage in contentious, collaborative, or any other type of tactics. Although these phases have been drawn from cognitive psychology, research has shown them to be applicable to the realm of social problems (see review by Rubin and Krasnor, 1986). If collaborative tactics are chosen by both parties, a joint problem-solving process may then occur that can be described with the same four phases.

The other approach emphasizes general social competencies such as communication skills, skills in finding common ground, and other social skills that are discussed in various chapters in this book. From this perspective, one of the primary social cognitive tasks that conflict presents to the individual is social perspective coordination . In other words, how do I understand the other’s perspective and develop an understanding of the situation that accounts for both that perspective and my own? Within this framework, a model of interpersonal negotiation strategies (INS) has been described that depicts a developmental progression in the ability to coordinate social perspectives in conflict, ranging from an egocentric inability to differentiate subjective perspectives (i.e., mine from yours) to the ability to coordinate the self’s and the other’s perspectives in terms of the relationship between them, or from a third-person viewpoint (Selman, 1980; Yeates, Schultz, and Selman, 1991). The functional steps of the INS model are similar to the steps articulated in information-processing approaches—that is, defining the problem, generating alternative strategies, selecting and implementing a specific strategy, and evaluating outcomes—but the INS model integrates additional developmental levels of perspective taking (egocentric, unilateral, reciprocal, and mutual) that underlie each of the functional steps (Selman, 1980). Here are descriptions adapted from Selman (1980) and Weitzman and Weitzman (2000):

- At the egocentric level, which is characterized by impulsive, fight-or-flight thinking, the other is viewed as an object and the self is seen as being in conflict with the external world. The types of behaviors that might be seen at this level are whining, fleeing, ignoring, hitting, cursing, or fighting.

- At the unilateral level, which is characterized by obeying or commanding the other person, although the other is now understood to have interests, the self is seen as the principal subject of the negotiation, with interests separate from the other. The types of behaviors typically seen at this level are threatening the other person, going behind the other’s back, avoiding the problem, or waiting for someone else to help.

- At the reciprocal level, which is characterized by exchange-oriented negotiations and attempts at influence, the needs of the other are appreciated but considered after the needs of the self. Typical behaviors are accommodation, barter, asking for reasons, persuasion, giving reasons, and appealing to a mediator.

- At the mutual level, which is characterized by collaborative negotiations, the needs of both the self and the other are coordinated, and a mutual, third-person perspective is adopted in which both sets of interests are taken into account. The types of behaviors that might be seen at this level are various forms of collaboration to develop satisfaction of mutual goals simultaneously.

In our work, we have used the INS model to explain the nature of everyday conflict in the lives of adults (Weitzman, 2001; Weitzman, Chee, and Levkoff, 1999; Weitzman and Weitzman, 2000). Our research has revealed some discontinuity between strategy choice and its social cognitive foundation. For example, in a study with elderly women, we found that although many women articulated reciprocal or mutual social perspective-taking skills, many of these same women opted for strategies associated with the unilateral level (Weitzman and Weitzman, 2000). Similarly, Yeates, Schultz, and Selman (1991) have shown that although the essential sequence of problem-solving steps is stable across conflict contexts, perspective taking often is not. Cultural norms (e.g., where older women are socialized to yield, particularly to men, rather than press to get their needs met), perceived power differentials between the parties in conflict, and other contextual factors may lead to the use of less sophisticated strategies, regardless of perspective-taking ability.

So even though the basic steps of individual problem solving remain fairly constant across situations, good, collaborative outcomes do not. The key issue this research brings to light is that an individual’s decision whether to coordinate his or her perspective with that of the other person is a central aspect of the conflict resolution process, one that may be highly relevant for training.

Critiques

There are also some serious critiques of problem-solving approaches to conflict resolution, and they deserve some attention here as well. For simplicity, we summarize them here as the Bush and Folger critique and the skeptic’s critique.

The Bush and Folger Critique.

Bush and Folger (1994) argue that problem solving, an orientation they see as underlying a “satisfaction story” of mediation (focusing only on satisfying the disputants and not taking advantage of the broader opportunities inherent in mediation), is narrow and mechanistic in that it assumes that conflict is a problem. This is seen as at odds with widely held values in the dispute resolution field to the effect that because of its capacity for stimulating growth and leading to change, conflict is a good thing.

We happen to share those values, but we believe there is a fundamental error in this critique. That is, Bush and Folger (1994) cast what the problem-solving mediator does as looking to solve problems in the first of the two senses we offered at the beginning of this chapter: problems as obstacles, difficulties, or predicaments, that is, “bad things.” The result is that their argument frames problem-solving approaches to mediation as more or less equivalent to the settlement-oriented style described by Kressel and colleagues (1994). This misses the fact that the work of Kressel and colleagues, Zubek and colleagues (1992), and others has found substantial differences between such approaches. Cooperative problem-solving approaches in mediation are working on a problem-as-puzzle model, which is very much consistent with the values of conflict as opportunity. If conflict is to be taken as an opportunity for change and growth, it is imperative that disputants move beyond fighting and take full advantage of the power of collaboration to develop new and better alternatives. That is the essence of problem-solving approaches. They can lead to transformation and empowerment of others as this approach becomes a general, personal orientation to resolving conflict.

The Skeptic’s Critique.

There is a skeptic’s critique often heard out in the field—during training or in conversation among practitioners—that says, “This is fine on paper, but it isn’t realistic.” In detail, it goes something like this. People are angry and do not want to solve problems, work with each other, or talk to each other. What may help to persuade those holding this view of problem solving is that research and practical experience are firm in their conclusions. People do respond better to problem-solving approaches than settlement-oriented ones, they reach agreement more often and faster, they report being more satisfied, and both agreements and satisfaction hold up better in the long run.

Another critique argues that people often do not know what actually constitutes “the problem,” and even when they think they do know, each side often has a very different problem in mind. Recall, however, that an essential part of what problem-solving approaches do is attempt to get the parties to focus on identifying the issues at the heart of their quarrel (in other words, to diagnose the nature of their conflict), and do not assume that those central, underlying issues are already known. They then ask the parties to treat the collection of issues (or needs or interests or other types of concern) on the table as a mutual problem to be solved collectively. Note that there is no assumption here that the parties have the same basic issues in mind as they approach the negotiating table, and they do not define their conflict in terms similar enough even to give it the same name. The core of problem-solving approaches is helping parties see their own interest in finding solutions that meet not only their needs but those of the other as well. That is often hard to do, and so there is this challenge: What kind of solution can we come up with such that my needs, which are A, B, and C, and your needs, which are X, Y, and Z, can all be met at least acceptably well? It is this puzzle that is the problem to be solved.

DECISION MAKING

Consider again, briefly, our simple PSDM model (figure 9.1 ). We suggested that decision making is going on both during and after the problem-solving process. At both of those points, there are decisions that each party makes individually and decisions made by the parties together. In the following discussion, we look first at the individual as decision maker and then at group decision making.

First, we offer a broad summary. Many of the theorists whose work is mentioned here define the negotiation process itself in decision-making terms (e.g., Bazerman and Neale, 1986; Kahneman, 1992; Zey, 1992). Some taking this view conceptualize each party as a decision maker (e.g., Kahneman, 1992; Mann, 1992), while others focus on the conflict resolution process as one of joint decision making (e.g., Bennett, Tait, and Macdonagh, 1994; Brett, 1991). It is possible, on the one hand, to think of the negotiator as someone with a series of decisions to make in the course of a negotiation, ultimately leading to the decision of whether to agree to a particular solution. On the other hand, one can also think about the process of negotiation as one of joint decision making, in which two or more parties with differing interests must jointly reach a decision—the resolution they ultimately agree to. In fact, many clients, when engaging a third-party mediator, describe their conflicts precisely as decision-making problems in which people are having a hard time making a decision together.

The Individual as Decision Maker

The emphasis here is on the problem of choice among alternatives, be they alternative agreements or alternative actions to take along the way. Many theories of decision making emphasize the notion of rational choice and are built on the notion of expected utility. The expected-utility principle has been traced as far back as the eighteenth-century to theorist Bernoulli (Abelson and Levi, 1985). The idea is that risky decisions involve choices in which we cannot be certain of what will happen as a result of our choice (as when a negotiator decides to hold out for a larger concession). For each option, we have to consider (1) the likelihood (expectation) that making this choice will get us what we hope it will and (2) the value, or utility, we attach to that outcome. Assuming that both the probability and the utility can be expressed as numbers, the expected utility for each option, then, is the product of probability and the associated utility. Thus “the expected-utility principle says that preferences between options accord with their relative expected utilities” (Abelson and Levi, 1985, p. 244). In conflict resolution, this principle would imply that people’s preferences among outcomes, possible settlements, or offers will be determined rationally according to the expected-utility principle.

Various limits to this approach have been discovered, however, and they have led to a number of useful ideas. Here we briefly summarize a few of the key findings and theories.

Anchors, Frames, and Reference Points.

It turns out that anchors, frames, and reference points can influence decision-making processes in such ways that people do not make the kinds of choices that the “rational” decision-making model predicts. The description here follows Kahneman (1992), whose excellent review is recommended to those interested in pursuing these ideas in detail.

The reference point in a negotiation is the point above which the party considers an outcome to be a gain and below which any outcome is considered a loss. In a given negotiation, several reference points might be available to a party: the status quo, the party’s opening offer, the other side’s initial offer, a settlement reached in a comparable case, and so on. Depending on which reference point a party has in mind, a given outcome might be seen (or framed ) as a gain or a loss. The central finding here is that people tend to be loss averse: avoiding loss is more important than achieving gain, and “concessions that increase one’s losses are much more painful than concessions that forgo gains” (Kahneman, 1992, p. 298). As a result, when faced with a possible loss, people become more willing to take risks rather than accept a large loss. For example, one may be inclined to risk impasse, rather than make an offer accepting a large loss. By contrast, if there is a possibility of gain, people tend to be less willing to take a risk (perhaps of impasse) in the hope of yet larger gains. If a decision is framed negatively (as one between losses), then people tend to be more risk prone than if it is framed positively (as one between gains). There is an important exception to this effect: if the goods being lost or gained are desirable only, or mainly, to be used in exchange (money kept for spending, goods kept for trading), then giving them up may not be viewed as a loss, and concessions may not be as painful (Kahneman, 1992).

Anchors are salient values that influence our thinking about possible outcomes, much like reference points. The difference is that whereas reference points define the neutral point between gains and losses, anchors may be anywhere along the scale and are often at the extremes. One of the most striking of anchoring effects is that negotiators are often unduly influenced by an anchor that they clearly know to be irrelevant—such as an outrageously low offer. Kahneman defines anchoring effects as “cases in which a stimulus or message that is clearly designated as irrelevant and uninformative nevertheless increases the [perceived] normality of a possible outcome” (1992, p. 308). There are a great many subtleties to the effects of anchors. The critical point for conflict resolution is recognizing their existence and developing methods for coping with their influence.

Impact of Stress.

Conflict often produces psychological states, such as stress, and affective (emotional) reactions that include anxiety, anger, and elation (Mann, 1992), thus introducing another set of barriers to “rational” decision making. From the perspective of Janis and Mann’s conflict theory of decision making (1977), there are important linkages among stress, conflict, and coping patterns (Janis, 1993; Mann, 1992). According to Mann, “the model is founded on the assumption that decisional conflict is a source of psychological stress. The task of making a vital decision is worrisome and can cause anxiety reactions such as agitation, quick temper, sleeplessness or oversleeping, loss of appetite or compulsive overeating, and other psychosomatic symptoms” (p. 209).

From this perspective come a number of interesting findings. Cognitive functioning in decision making declines under stress; time pressure increases stress and thus negatively affects decision making, as well as reduces the willingness to take risks; and mood has predictable effects on risk taking: when in a good mood (compared to a neutral mood), people are more risk seeking when the risk is low but less risk seeking when risk is high. This pattern appears to reflect the fact that in a good mood, people think more about loss under high-risk situations, but they think less about loss when risk is low (Mann, 1992).

Another View of Risk.

In the previous sections, we discussed some of the impact of framing, stress, emotion, and mood on risk taking. Taking a slightly different view, Hollenbeck and his colleagues have argued that much of the research on risky decision making is limited in that it uses decisions that are static: they involve a one-shot decision with no future implications, no effect of past performance, and a high degree of specificity about outcomes and probabilities (Hollenbeck, Ilgen, Phillips, and Hedlund, 1994). By contrast, most decisions in conflict situations do not meet these conditions. Hollenbeck and colleagues conducted an experiment in which they varied these conditions and found that giving a general do-your-best goal instead of a specific goal actually reversed the framing effect that Kahneman and Tversky (1984) described. Hollenbeck and colleagues conclude that to better understand the conditions that lead to risk taking, we need to know more about dynamic contexts, and we cannot freely generalize findings from static settings.

An Applied Approach.

Approaches such as that of Janis and Mann (1977) are close in flavor to problem-solving approaches in being analytical and depersonalizing the conflict. In this approach, a decision maker fills out a “decisional balance sheet,” listing all outcomes, weighting and summing costs and benefits, and thus analyzing the relative costs and benefits of each choice in order to make a decision. If the parties are willing to undertake the process together, they may be able to arrive at a decision they can agree to accept. But this approach makes some serious errors (as do others like it). In particular, it assumes that preferences on all issues can be translated into a common currency. This may be workable in some circumstances, as in a divorce mediation, for weighing relative preferences for the pots and pans on the one hand and a painting on the other. But it may be much less workable for weighing relative preferences for the house, on the one hand, and custody of the children, on the other, since the house and the children do not readily convert into a common currency.

Group Decision Making and Commitment

Viewing negotiation as joint decision making opens up the possibility of exploring such decisional biases as overconfidence and lack of perspective taking—processes about which there is knowledge in the decision-making domain—that may alter performance and dispute resolution behavior (Bazerman and Neale, 1986).

Behavioral Decision Making.

One prominent, and particularly helpful, approach to understanding group decision making is known as behavioral decision making (BDM). BDM emphasizes rational negotiation, with the goal of making decisions that maximize one’s interests (Bazerman and Neale, 1992). Bazerman, Neale, and their colleagues have conducted an extensive program of research based on this approach (Bazerman and Neale, 1986; Loewenstein, Thompson, and Bazerman, 1989; Mannix and Neale, 1993; Neale and Bazerman, 1992; Thompson and Loewenstein, 1992; Valley, White, Neale, and Bazerman, 1992). Their findings are informative in terms of understanding conflict and working to resolve it. From a behavioral decision theory perspective, negotiation is seen as “a multiparty decision making activity where the individual cognitions of each party and the interactive dynamics of multiple parties are critical elements” (Neale and Bazerman, 1992, p. 157). The approach aims at being both descriptive and prescriptive, and it works with such concepts as the perceptions of the negotiators, their biases, and their aspirations.

Bazerman and Neale (1992) offer a list of seven pervasive decision-making biases that interfere with the goal of negotiating rationally to maximize one’s interests. The first is “irrationally escalating your commitment to an initial course of action, even when it is no longer the most beneficial choice” (p. 2). Possible causes of this bias include the competitive irrationality that can ensue when winning becomes more important than the original goal and also the biases in perception and judgment resulting from our tendency to seek information that confirms what we are doing and avoid information that challenges us.

The second bias is “assuming your gain must come at the expense of the other party, and missing opportunities for tradeoffs that benefit both sides” (Bazerman and Neale, 1992, p. 2). Earlier, we discussed some of the benefits of approaching mixed-motive conflict as potentially integrative rather than purely distributive. Bazerman and Neale argue that “parties in a negotiation often don’t find these beneficial trade-offs because each assumes its interests directly conflict with those of the other party” (p. 16). They call this mind-set the mythical fixed pie .

The third bias is “anchoring your judgments upon irrelevant information, such as an initial offer” (Bazerman and Neale, 1992, p. 2). (For more on anchoring, see our earlier discussion in the “Anchors, Frames, and Reference Points” section.)

The fourth is “being overly affected by the way information is presented to you” (Bazerman and Neale, 1992, p. 2). This refers to the effect of framing, discussed earlier. Bazerman and Neale suggest that a mediator who wants to encourage parties to compromise should work to help the parties see the conflict in a positive frame, one emphasizing gains rather than losses.

The fifth bias, “relying too much on readily available information, while ignoring more relevant data” (Bazerman and Neale, 1992, p. 2), has obvious implications for the quality of decisions. Bazerman and Neale urge negotiators to work to counteract this bias. Similarly, we urge mediators to be on the lookout for this tendency, both in disputants and in themselves.

The sixth bias, “failing to consider what you can learn by focusing on the other side’s perspective” (Bazerman and Neale, 1992, p. 2), takes a somewhat different slant on perspective taking from those presented earlier. In their version, emphasis is on gaining information about the other side’s motives by paying attention to their actions and taking their perspective into account.

The final bias, “being overconfident about attaining outcomes that favor you” (Bazerman and Neale, 1992, p. 2), is a particularly important one. Through anchoring on one’s own initial proposal, failing to learn from considering the other side’s perspective, distorting one’s perceptions of the conflict situation in order to feel better about oneself, and focusing too strongly on information that supports one’s position and ignoring information that challenges it, parties to a dispute often become overconfident in their ability to win; as a result, they miss out on opportunities to create integrative solutions. Thus, mediators in court-connected mediation programs may be faced with two parties, each absolutely certain that if they fail to settle the dispute, the judge or jury will find in their favor.

Let us now briefly discuss a number of other findings from the work of Bazerman, Neale, and their colleagues.

Power Imbalance.

In an experimental study of the effects of power imbalance and level of aspiration, Mannix and Neale (1993) found that in a negotiation with integrative potential, (1) higher joint gains were achieved when power was equal than when unequal; (2) higher joint gains were achieved when aspirations were high rather than low; and (3) when power was unequal, higher joint-gain solutions tended to be driven by the offers of the low-power party. That is, in unequal power situations, the high-power party was less likely to initiate a joint-gain solution. As a result, the onus of generating and selling a joint-gain solution appeared to fall on the low-power party.

Interpretations of Fairness.

Thompson and Loewenstein (1992) found a tendency among negotiators, in a simulation of a collective bargaining process, to make “egocentric interpretations of fairness.” That is, participants tended to assess fairness with a bias toward their own interests. This led to discrepancies between what each party saw as fair, each side tending to an interpretation benefiting themselves. Furthermore, “the more people disagreed in terms of their perception of a fair settlement wage, the longer it took them to reach a settlement” (p. 184). Perhaps more surprising, providing the subjects with more background information, which might be expected to reduce bias, served only to exacerbate the self-serving nature of fairness assessments. (For more on biases, see chapter 11.)

Preferences in Different Types of Relationships.

Finally, in a study that bears directly on our earlier discussion of problem solving, Loewenstein, Thompson, and Bazerman (1989) found that people’s preferences for doing better than the other in disputes depended strongly on the nature of the relationship between the parties. The researchers manipulated two aspects of the dispute relationship: whether it was a business or personal dispute and whether the relationship between the parties was positive, negative, or neutral. They found that although parties (across combinations of dispute type and relationship) did not like outcomes in which they did more poorly than the other, there were substantial differences in how much parties preferred an outcome in which they did better than the other. First, in a negative relationship, disputants tended to like doing better than the other, while in a positive or neutral relationship, disputants tended to dislike doing better than the other (up to a certain high amount of gain, after which their preferences begin to rise again). Similarly, in business disputes, participants liked doing better than the other, but in personal disputes, they disliked doing better than the other (again, up to a point). Significantly, these two tendencies reinforced each other; in business disputes, the preference for doing better was substantially enhanced in a negative relationship.

This study may have profound implications for the problem-solving approaches we have discussed. In particular, it tells us that in certain situations (such as a business dispute or negative relationship) people may be highly motivated to create a large difference between what they and their negotiating partners receive. Such motivation runs directly counter to the goal of the cooperative problem-solving approaches: to engage parties in maximizing mutual gain.

UNDERSTANDING PROBLEM SOLVING AND DECISION MAKING IN CONFLICT SITUATIONS

Our simple model of the interaction of problem solving and decision making in conflict resolution (figure 9.1 ) offers a framework for integrating what we know about these processes. In this section, we take a brief walk through the PSDM model, illustrating some of the ways these findings and perspectives can be used to enhance our understanding of conflict.

The PSDM Model Revisited

We have proposed that problem solving and decision making be viewed as integral parts of the cooperative conflict resolution process. We have also suggested that decision making takes place both during and after problem solving and that at each point, some decisions are made by the parties as individuals and some by the parties together.

Both problem-solving and decision-making approaches to conflict resolution, be they conscious designs of the professional mediator or spontaneous behaviors by the most naive of disputants, fundamentally work with the basic dynamics of cooperation and competition, as discussed at greater length in other parts of this book (see chapter 1). Briefly, if conflict is approached as a cooperative endeavor in which the parties see their outcomes as positively correlated, people tend to work hard to create a resolution that maximizes both parties’ outcomes. The goal becomes to do as well as possible for both self and other , rather than to engage in the kind of destructive win-lose struggle that exemplifies competitive, contentious conflict.

In the kind of integrated view we are taking, cooperative conflict resolution consists of four general phases: (1) diagnosing the conflict, (2) identifying alternative solutions, (3) evaluating and choosing a mutually acceptable solution, and (4) committing to the decision and implementing it. The left-hand part of the PSDM model (figure 9.1 ) is concerned primarily with phases 1 and 2, with both problem solving and decision making taking place. The right-hand part of the model, labeled “Decision making after ,” is concerned primarily with phases 3 and 4, where the solutions generated must be selected and committed to. As indicated in the model, if it becomes clear during phases 3 or 4 that an adequate solution has not been generated, it is necessary to return to the problem-solving process, looking for further solutions and, if necessary, reconsidering the original diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is the first part of the problem-solving process. Perhaps the first step in diagnosis involves an important decision: determining what kind of conflict you are in. A fundamental problem in conflict resolution in applied work is determining those few conflicts that really are not amenable to a constructive, integrative approach.

Determining What Kind of Conflict You Are In.

Often we are working to convince our students and those we train that most of the conflicts initially appearing to be unalterably competitive, zero-sum situations by their nature are in fact at worst mixed motive. Many of us even take an initial, dogmatic stance with students that there are virtually no cases in which collaborative approaches are impossible, in an effort to break them of the common tendency to respond competitively (Bazerman and Neale, 1992). (At least the first author of this chapter knows he is guilty of this.) Yet we know from practical experience, as well as some of the research findings discussed earlier, that this is not the case. It would seem naive to deny that there are situations in which power-wielding, contentious tactics are warranted. Books such as Bazerman and Neale’s that alert readers to common biased misperceptions and urge them to look more closely are an important start. A set of empirically and theoretically justified principles, guidelines, or frameworks are badly needed to help identify those cases that really are immutably contentious.

This would serve at least two aims. It would be an indispensable tool for conflict resolution efforts both in the first person and by a third-party intervenor. It would also give us the ability to say to our students, “Here’s how you know a case that really can’t be transformed into a ‘mutual problem to be solved collaboratively.’ If it doesn’t meet these criteria, the potential is in there somewhere. Now let’s work on how to find it.”

Identifying the Problem or Problems.

The next step in diagnosis is to develop an understanding of what the conflict is about—whether in substantive interests, values, or other types of concerns—that lends itself to problem solving. This involves identifying each side’s real concerns (getting past initial positions or bargaining gambits) and developing a common understanding of the joint set of concerns of each party. Some questions that might be asked or investigated at this stage include

- What do I want?

- Why do I want it?

- What do I think are the various ways I can satisfy what I want?

- What does the other want?

- Why?

- What are the various ways the other believes he or she can satisfy his or her wants?

- Do we each fully understand one another’s needs, reasons, beliefs, and feelings?

- Is the conflict based on a misunderstanding, or is it a real conflict of interests, beliefs, preferences, or values?

- What is it about?

Finally, during the diagnosis phase, social perspective coordination is important. To arrive at a joint diagnosis, parties have to be willing and able to appreciate the other as a person, with concerns of his or her own, and coordinate these concerns with the party’s perspective so as to create the joint diagnosis.

Identifying Alternative Solutions

Once the parties have reached a joint diagnosis, the next step is to begin generating alternative solutions that may meet each party’s goals at least acceptably well. One of the most commonly mentioned approaches to doing this is brainstorming. Here, the emphasis is on generating as many creative ideas as possible, hoping to encourage parties to think of the kinds of mutually acceptable solutions that have eluded them. Most brainstorming sessions employ a “no evaluation” rule: during the brainstorming session, no comments on proposed ideas are allowed, in the hope of encouraging parties to think of as many ideas as they can, no matter how silly or impractical. Once a list of alternatives is on a blackboard or newsprint, parties are often able to begin sorting through them and find options that are workable.

A list of other techniques is suggested by Treffinger, Isaksen, and Dorval (1994). For example, they recommend “idea checklists,” lists of idea-stimulating questions such as, “What might you do instead?” or “What might be changed or used in a different way?” (p. 43). They also recommend using metaphors or analogies to stimulate creativity and blending active strategies (like brainstorming) with reflective strategies (such as built-in down time, for thinking things over).

In our earlier discussion of decision making, we emphasized research concerned with decision making under conditions of risk. Risk taking is important in this context in at least two ways. The research we have reported focused on the willingness to hold to a position and risk impasse—a risky decision that works against cooperative conflict resolution. But there are other kinds of risks where such a course of action is desirable. For example, offering a concession (or an apology!) can feel like a risk if you are not sure it will be reciprocated. In building trust where it is lacking between parties in conflict, it is often necessary to get one of the parties to take a risk and demonstrate trust in order to persuade the other party to begin trusting.

Social perspective coordination is important here as well. To create viable solutions that meet each party’s concerns, it is helpful—if not essential—for parties to be able to grasp and appreciate the importance of the other’s perspective and choose to engage in the search for solutions that satisfy the other’s concerns.

Evaluating and Choosing

Once a set of possible alternative solutions has been identified, the next task is to evaluate the various options and choose among them. This involves a variety of individual decisions: about preferences among the advantages the options offer, about which seem fairer, which are likely to last, and so on. As the parties make these decisions, such factors as stress, anchors, frames, and reference points may all play a role in interfering with reasonable, rational decision making. Procedures such as Janis and Mann’s decisional balance sheet exercise (1977) may be helpful here, as may the recommendations offered by Bazerman and Neale (1992) for overcoming biases.

There are also, at this stage, group decisions to be made, primarily as to which option is chosen. Several of the behavioral decision-making findings are important here, largely as things that negotiators as well as mediators and other third parties should look out for. Integrative solutions, for example, are more likely if power is relatively equal, and they tend to be driven by the low-power party if it is not (Mannix and Neale, 1993). There is a tendency to egocentric interpretations of fairness (Thompson and Loewenstein, 1992), which can add a sense of moral justification, and thus intractability, to a party’s sense of need. Also, people are less interested in doing better than the other (a competitive goal) when the relationship is personal and when it is positive (Loewenstein, Thompson, and Bazerman, 1989). Again, procedures such as that of Janis and Mann (1977) may be helpful.

Committing to a Choice

Finally, once a mutually agreeable solution has been found, the decision must be made to enter into agreement. Trust and the attendant risks are important factors. It is critical that parties be willing to put mutual satisfaction before the goal of “doing better than the other.” Social perspective coordination is important again, and here the issue of choosing to act on the social understanding gained is crucial; it is not enough just to understand; understanding must be translated into willingness to act. Among the key factors suggested by our work with elderly women (Weitzman and Weitzman, 2000) for encouraging this translation are beliefs that the agreement will really work and be abided by and that the costs, emotional and otherwise, will not be too high.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TRAINING AND PRACTICE

We suggest that rather than being taught separately, in different training programs, problem-solving and decision-making approaches to cooperative conflict resolution should be taught together in integrated fashion. In the previous section, we made an argument for considering the conflict resolution process in roughly four phases, incorporating problem solving and decision making throughout. We also recommend the development of training programs and intervention designs that approach the process in the same way. In this section, we briefly highlight a few factors that should be part of such efforts.

Conditions That Encourage Problem Solving

Training in problem-solving approaches should include information about the conditions that are likely to lead to parties’ willingness to engage in problem solving. We know, for example, that a psychological climate characterized by cohesion, fairness, recognition of success, and openness to innovation encourages people to choose problem-solving and persuasion strategies, and less likely to engage in bargaining and politicking (Strutton, Pelton, and Lumpkin, 1993). Training for mediators, designs for organizational alternative dispute resolution programs, and conflict resolution programs for high schools, to name a few, could all make use of this information.

In addition, encouraging problem solving through cultivating concern for the other can be important (e.g., Carnevale and Pruitt, 1992; Pruitt and Kim, 2004). One common approach is to engage parties in perspective taking to help them see the other’s concerns as legitimate. Our work on social perspective coordination (Weitzman and Weitzman, 2000) suggests not only that people must learn to take the perspective of the other but also that attention must be paid to translating perspective-taking ability into the choice of conflict resolution strategy. (See chapters 1 and 3 for more on the conditions that encourage conflict resolution.)

Although working to improve conditions that encourage problem solving is important, it is also essential to provide people with the tools to do it well. Trainings and intervention plans should include the sorts of specific problem-solving techniques referred to earlier, such as expanding the pie, logrolling, nonspecific compensation, and bridging. Furthermore, a consideration of some of the issues raised here can lead to novel approaches to intervention. To take an example from our practice, we were asked to mediate a community dispute in which there were known to be many “sides” with different perspectives. A consideration of the concern discussed as a critique, that people may not agree on a definition of the problem in the first place and that this alone can undermine conflict resolution efforts, led to an approach based on the very issue of problem definition. A group of about thirty community members were asked to begin the “mediation” session by engaging in brainstorming definitions of “the problem” they were facing. As the session proceeded, the group gradually worked toward a mutually agreed definition of the problem. By the time the group reached agreement on a definition of the problem, the solution was close to obvious and was easily agreed to.

Teaching the Lessons from the Decision-Making Literature

The information from the decision-making literature that would be particularly helpful if built into conflict resolution training includes the concepts of anchors, frames, and reference points. Kahneman (1992) suggests what he calls the Lewinian prescription, based on the concept of loss aversion: concessions that eliminate losses are more effective than concessions that improve on existing gains. Mediators as well as negotiators could learn to look for these opportunities.

Earlier, we presented selected information about the decision-making phenomena that help explain and predict disputant behavior. Such information is often incorporated into negotiation training aimed at “winning” in competitive negotiations, but it seems, at least anecdotally, much less often to be a part of mediation training. Yet understanding issues such as the impact of stress, power imbalance, disclosure of information, egocentric interpretations of fairness, and preferences for relative outcomes, as well as the role of issues of risk taking and the factors that influence risk-taking propensity, would seem to be of enormous value for mediators.

One more approach from the decision-making literature needs introduction here. Building on the sort of literature described earlier, Brett argues for “transforming conflict in organizational groups into high quality group decisions” (1991, p. 291) and prescribes techniques for doing so. Her approach is based in the assumption that by harnessing negotiation and decision theory, one can bring conflict to a constructive outcome through a decision-making approach. Her prescriptions include

- Criteria for determining if a high-quality decision has been reached

- Guidelines for improving the decision-making process

- Methods for integrating differing points of view

- Tactics for creating mutual gain, coalition gain, and individual gain

- Choosing decision rules that maximize integration of information

- Guidelines about when to use mutual gain, individual gain, and coalition gain approaches

This approach offers concrete, structured advice, based solidly in the research literature, for applying decision-making techniques to resolving group conflict. These techniques can be helpful at many of the decision-making moments identified in the PSDM model.

In a similar vein, Janis and Mann’s approach (1977) suggests that parties sit down together and analyze their conflict as a difficult decision. Their book offers devices such as the decisional balance sheet, a form for listing choice criteria (the things that matter to each party), assigning numerical values and valences (1 or 2) to each, and manipulating the results. In this approach, disputants sit down together with a decisional balance sheet, carefully consider their own and the other’s concerns, and look for a solution that maximizes each side’s benefit and minimizes cost. With reference to the PSDM model presented here, such techniques might be helpful at the stage of either generating alternatives or choosing among alternatives; in fact, it bridges the two.

Approaches such as those of Brett (1991) and Janis and Mann (1977) represent formalized, detailed technologies that can and should be taught more widely than they currently are. Though we have criticized some underlying assumptions of some of these approaches (questioning, for example, the common currency assumptions in the Janis and Mann approach), they remain tools that can be of great value if applied appropriately and as tools integrated into a problem-solving and decision-making approach. Our training programs would benefit from offering students more in the way of such concrete, specified techniques for incorporation into their tool kits.

CONCLUSION

We have suggested that problem solving and decision making are processes interwoven in many cooperative conflict resolution procedures and have proposed an integrated PSDM model reflecting four general phases: (1) diagnosing the conflict, (2) identifying alternative solutions, (3) evaluating and choosing a mutually acceptable solution, and (4) committing to the decision and implementing it. This integrated model offers a way of thinking about the opportunities for applying both problem-solving and decision-making knowledge and techniques. An understanding of how problem-solving approaches work, are helpful, and can be encouraged in various contexts can be a critical component of training, intervention, and dispute-resolution program design. Similarly, an understanding of decision-making biases and strategies for overcoming them can be a vital component of both conflict resolution education and practice. Furthermore, a consideration of the issues raised here, and even of some of the critiques of these approaches, can lead to new approaches to intervention, training, and program design.

References

Abelson, R. P., and Levi, A. “Decision Making and Decision Theory.” In G. Lindzey and E. Aronson (eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology , Vol. 1. (3rd ed.) New York: Random House, 1985.

Bazerman, M. H., and Neale, M. A. “Heuristics in Negotiation: Limitations to Effective Dispute Resolution.” In H. R. Arkes and K. R. Hammond (eds.), Judgment and Decision Making: An Interdisciplinary Reader . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Bazerman, M. H., and Neale, M. A. Negotiating Rationally . New York: Free Press, 1992.

Bennett, P., Tait, A., and Macdonagh, K. “Interact: Developing Software for Interactive Decisions.” Group Decision and Negotiation , 1994, 3 , 351–372.

Brett, J. M. “Negotiating Group Decisions.” Negotiation Journal , 1991, 7 , 291–310.

Bush, R.A.B., and Folger, J. P. The Promise of Mediation: Responding to Conflict Through Empowerment and Recognition . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994.

Carnevale, P. J., and Pruitt, D. G. “Negotiation and Mediation.” Annual Review of Psychology , 1992, 43 , 531–582.

Dant, R. P., and Schul, P. L. “Conflict Resolution Processes in Contractual Channels of Distribution.” Journal of Marketing , 1992, 56 , 38–54.

Dodge, K. A. “Social Cognition and Children’s Aggressive Behavior.” Child Development , 1980, 51 , 162–170.

Hollenbeck, J. R., Ilgen, D. R., Phillips, J. M., and Hedlund, J. “Decision Risk in Dynamic Two-Stage Contexts: Beyond the Status Quo.” Journal of Applied Psychology , 1994, 79 , 592–598.

Janis, I. L. “Decision Making Under Stress.” In S.B.L. Goldberger (ed.), Handbook of Stress: Theoretical and Clinical Aspects . (2nd ed.) New York: Free Press, 1993.

Janis, I. L., and Mann, L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment . New York: Free Press, 1977.

Kahneman, D. “Reference Points, Anchors, Norms, and Mixed Feelings.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 1992, 51 , 296–312.

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. “Choices, Values, and Frames.” American Psychologist , 1984, 39 , 341–350.

Kressel, K., and others. “The Settlement-Orientation vs. the Problem-Solving Style in Custody Mediation.” Journal of Social Issues , 1994, 50 , 67–84.

Loewenstein, G. F., Thompson, L., and Bazerman, M. H. “Social Utility and Decision Making in Interpersonal Contexts.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 1989, 57 , 426–441.

Mann, L. “Stress, Affect, and Risk Taking.” In J. F. Yates (ed.), Risk-Taking Behavior . New York: Wiley, 1992.

Mannix, E. A., and Neale, M. A. “Power Imbalance and the Pattern of Exchange in Dyadic Negotiation.” Group Decision and Negotiation , 1993, 2 , 119–133.

Neale, M. A., and Bazerman, M. H. “Negotiator Cognition and Rationality: A Behavioral Decision Theory Perspective.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 1992, 51 , 157–175.

Pruitt, D. G., and Kim, S. H. Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate, and Settlement . (3rd ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Pruitt, D. G., and Rubin, J. Z. Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate, and Settlement . New York: Random House, 1986.

Rubin, J. Z., Pruitt, D. G., and Kim, S. H. Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate, and Settlement . (2nd ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

Rubin, K. H., and Krasnor, L. R. “Social-Cognitive and Social Behavioral Perspectives on Problem Solving.” In M. Perlmutter (ed.), Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology . Vol. 18. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1986.

Selman, R. L. The Growth of Interpersonal Understanding . Orlando, FL: Academic Press, 1980.

Spivack, G., and Shure, M. The Social Adjustment of Young Children . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1976.

Strutton, D., Pelton, L. E., and Lumpkin, J. R. “The Influence of Psychological Climate on Conflict Resolution Strategies in Franchise Relationships.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 1993, 21 , 207–215.

Thompson, L., and Loewenstein, G. “Egocentric Interpretations of Fairness and Interpersonal Conflict.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 1992, 51 , 176–197.

Treffinger, D. J., Isaksen, S. G., and Dorval, K. B. Creative Problem Solving: An Introduction . (Rev. ed.) Sarasota, Fla.: Center for Creative Learning, 1994.

Valley, K. L., White, S. B., Neale, M. A., and Bazerman, M. H. “Agents as Information Brokers: The Effects of Information Disclosure on Negotiated Outcomes.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 1992, 51 , 220–236.

van de Vliert, E., Euwema, M. C., and Huismans, S. E. “Managing Conflict with a Subordinate or a Superior: Effectiveness of Conglomerated Behavior.” Journal of Applied Psychology , 1995, 80 , 271–281.

Weitzman, P. F. “Young Adult Women Resolving Interpersonal Conflicts.” Journal of Adult Development , 2001, 8 , 61–67.

Weitzman, P. F., Chee, Y. K., and Levkoff, S. E. “A Social Cognitive Examination of Responses to Conflicts by African-American and Chinese-American Family Caregivers.” American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease , 1999, 14 , 343–350.

Weitzman, P. F., and Weitzman, E. A. “Interpersonal Negotiation Strategies in a Sample of Older Women.” Journal of Clinical Geropsychology , 2000, 6 , 41–51.

Yeates, K. O., Schultz, L. H., and Selman, R. L. “The Development of Interpersonal Negotiation Strategies in Thought and Action: A Social-Cognitive Link to Behavioral Adjustment and Social Status.” Merrill-Palmer Quarterly , 1991, 37 , 369–403.

Zey, M. (ed.). Decision Making: Alternatives to Rational Choice Models . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1992.

Zubek, J. M., and others. “Disputant and Mediator Behaviors Affecting Short-Term Success in Mediation.” Journal of Conflict Resolution , 1992, 36 , 546–572.