CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

PERSONALITY AND CONFLICT

Sandra V. Sandy

Susan K. Boardman

Morton Deutsch

Throughout literary history, many novelists and playwrights have defined personality as “destiny,” poignantly illustrating the “inevitability” of their protagonist’s fate as a consequence of character traits that relentlessly determine his or her choices in life. Even as naive observers, if we look deeply enough within ourselves, we are often surprised by the extent to which we are ruled by needs and strivings that defy commonsense logic. Although many social scientists agree with the fiction writers on the power of personality to shape the course of our lives, scientists focus on predictability rather than inevitability. The task of science is to observe and document any reliable association between specific character traits and the likelihood of varying life choices, patterns of behavior, and consequences of the behavior for oneself and others.

Parties involved in a conflict they are attempting to resolve constructively must strive to understand each other despite any difference in ethnic and gender identities, family and life experiences, and cultural perspectives. Although conflict resolution practitioners and theorists recognize the potentially important effects that individual differences have on the negotiation process and its outcome, research in this area has been piecemeal, and few guidelines exist for practical application. At this stage, a synthesis of cross-discipline information concerning personality can offer additional tools to benefit practitioners and prove useful to theorists wishing to conduct future investigation in this area. Awareness of how personal characteristics predispose an individual to respond within the negotiation setting equips all parties more effectively to (1) uncover and understand the psychological as well as substantive interests underlying conflict—particularly those interests that would normally remain unrecognized or unarticulated if personality is not considered; (2) respond so as to facilitate a constructive resolution process avoiding escalation and deadlock; and (3) generate a satisfying solution to meet the priority needs of both parties.

We have added new material to each section of this chapter to reflect some of the more relevant research—and thoughts about personality and conflict—conducted since the previous edition of this Handbook was published. This includes an introduction in the first section on the psychodynamic approach to some irrational deterrents to negotiation and their role in perpetuating conflict. In the section on need theories, we discuss some recent thoughts on the existence of a negative pole to Murray’s need for self-actualization. Finally, we discuss several relevant research studies that have appeared in print since the publication of the previous edition. These more recent studies relate to the influence of individual personality traits on choice of conflict resolution strategy and replicate some of the findings we presented in the second edition of this Handbook (Sandy, Boardman, and Deutsch, 2006).

As in previous editions, the first section of this chapter reviews some of the ideas relevant to conflict from several major theoretical approaches to personality: psychodynamic theory, need theory, social learning theory, and situation-person interaction theory. Our review of these theories is not intended to be comprehensive. It is limited to selecting several ideas from each theory that are useful to understanding personal reaction and behavior in a conflict situation. In the second section, we discuss the trait approach to personality and assessment. First, we briefly indicate some of the individual traits thought to be related to conflict behavior and then discuss some of the limitations of this approach. Next, we discuss more fully a multiple-trait approach, as well as a method for assessing personal conflict orientations that seem to have considerable promise for the evaluation of personality style, reaction, and behavior as they relate to conflict. In the final section, we discuss how one can use personality theory and assessment to enhance conflict resolution in practice.

REPRESENTATIVE MODELS OF PERSONALITY

There are two major approaches to the study of personality: idiographic, the belief that human behavior cannot be broken down into its constituent parts; and nomothetic, the view that some general dimension of behavior can be used to describe most people of a general age group (Martin, 1988). To illustrate, we begin by noting that one of the most influential models of personality, the psychodynamic, relies on idiographic use of case history studies to reach conclusions about human nature.

Psychodynamic Theories

Sigmund Freud’s work from the late 1880s to the late 1930s marks the beginning of the psychodynamic study of human personality. His intellectual descendants are numerous: Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, Karen Horney, Anna Freud, Erik Erikson, Erich Fromm, Harry S. Sullivan, Melanie Klein, W.R.D. Fairbairn, Donald Winnicott, Heinz Hartman, Jacques Lacan, and Heinz Kohut.

Much of early psychodynamic theory can be described as a drive theory, which is mainly concerned with the “vicissitudes of, and conflicts associated with libidinal and aggressive drives” (Gratch, 2012, p. 205). More recent versions of psychodynamic theory (which have the odd label of object relations theory ) consider social attachments and the internalization of one’s early social relations with significant others as the primary psychic determinants.

Inevitably, Freud’s descendants have modified, revised, extended, and in other ways changed his original ideas. The changes have mainly been to place greater emphasis on the social (cultural, class, gender, familial, and experiential) determinants of psychodynamic processes, develop detailed characterization of the structural components involved in the dynamic intrapsychic processes, and seek adequate conceptualization of the cognitive and self-processes that are central to the individual’s relation to reality. Despite these changes, which seek to integrate the biological and social determinants of personality development, some key elements characterize most of the psychodynamic approaches.

An Active Unconscious.

People actively seek to remain unaware (unconscious) of their impulses, thoughts, and actions that make them feel disturbing emotions (e.g., anxiety, guilt, or shame).

Internal Conflict.

People may have internal conflict between desires and conscience, desires and fears, and what the “good” self wants and what the “bad” self wants. This conflict may occur outside consciousness.

Control and Defense Mechanisms.

People develop tactics and strategies to control their impulses, thoughts, actions, and realities so that they will not feel anxious, guilty, or ashamed. If their controls are ineffective, they develop defense mechanisms to keep from feeling these disturbing emotions.

Stages of Development.

From birth to old age, people go through stages of development. Most current psychodynamic theorists accept the view that the developmental stages reflect both biological and social determinants, even though they may differ in their weighting of the two, their labeling of the stages, and how they specifically characterize them. Freudian theory focuses mainly on the three earliest stages of development—the oral, anal, and phallic—because it was believed that the main features of personality development were set early in childhood. Freud employed these anatomical terms to characterize the early stages because he thought these bodily zones were successively infused with libidinal energy.

Later psychoanalysts were likely to characterize them psychosocially in terms of the social situation confronting the developing child. In the oral stage, infants are primarily concerned with receiving feeding and care from a parenting figure; in the anal stage, they are faced with the need to develop control over their excretions as well as other forms of self-control; and in the phallic stage, they face the need to establish a sexual identity as a boy or girl and to repress their sexual striving toward the parent of the opposite sex. Associated with these stages are normal frustrations, a development crisis, and typical defense mechanisms. However, certain forms of psychopathology are likely to develop if severe frustration and crisis face the child during a particular stage, with the result that the child becomes “fixated” at that stage; in addition, some adult character traits are thought to originate in each given stage.

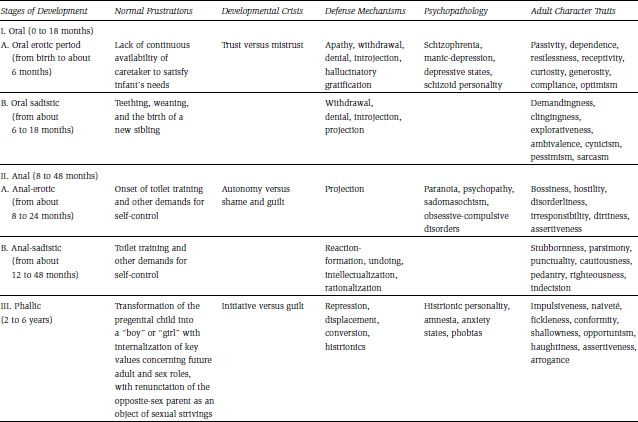

Table 17.1 presents, in summary form, some of the features that Freud and the earlier psychoanalysts associated with the three early stages.

Table 17.1 Normal Frustrations, Typical Defense Mechanisms, Developmental Crises, Psychopathology, and Adult Character Traits with Several Early Stages of Psychosexual Development

The Layered Personality.

How someone has gone through the stages of development determines his or her current personality. One can presumably discover the residue of earlier stages of development in current personality and behavior. Thus, a paranoid or schizoid adult personality supposedly reflects a basic fault in the earliest stage of development in which the infant did not experience the minimal love, care, and nurturance that would enable him to feel basic trust in the world. The concept of layered personality does not imply that earlier faults cannot be repaired. However, it does imply that an adult personality with a repaired fault is not the same as one that did not need repair. Under severe frustration or anxiety, such a personality is likely to regress to an earlier stage. Also, the concept of layered personality does not imply that an unimpaired adult personality is able to completely resist becoming temporarily or permanently suspicious and paranoid if the current social environment is sufficiently dire and hostile for a prolonged period. It is natural and adaptive to become hypervigilant and suspicious if one is immersed in a dangerous hostile environment.

In this section, we discuss several important ideas deriving from the work of psychodynamic theorists that are particularly relevant to conflict practitioners. Undoubtedly, many more ideas could be expressed in a detailed and comprehensive exposition of psychodynamic viewpoints than we attempt to present in this chapter.

Conflict with Another Can Lead to Intrapsychic Conflict and Anxiety.

People may feel anxious because they sense they are unable to control their destructive or evil impulses toward the other in a heated conflict. Or the conflict may lead to a sense of helplessness and vulnerability if they feel overwhelmed by the power and strength of the other. Freud called the first type of internal conflict id-superego conflict (between a primitive impulse and conscience) and the second type an ego-reality conflict (between an immature self and a threatening reality). Later psychoanalysts used somewhat different language, speaking of a conflict among “internal objects” or between internalized images of self and of significant adults (as between an evil self and a harsh or punitive parent or a weak self and an overwhelming, controlling parent).

If the anxiety aroused by the conflict with another is intense, the individual may rely on unconscious defense mechanisms to screen it out in an attempt to reduce the anxiety. Anxiety is most likely to be aroused if one’s basic security, self-conception, self-worth, or social identity is threatened. Defense mechanisms are pathological or ineffective if they create the conditions that produce anxiety, thus requiring continued use of the defense. For example, a student who may be anxious about his intellectual abilities avoids studying and as a consequence does poorly in his course work. He rationalizes that his poor grades are due to lack of motivation and effort. His grades further his anxiety about his ability, which in turn fuels his defenses of avoidance and rationalization. The defenses would not be pathological if in fact external circumstances had prevented him from studying and, given the opportunity, he would have put much effort into his studies.

The defense mechanisms that people use are determined in part by their layered personality, which may have given rise to a characterological tendency to employ certain defense mechanisms rather than others, and also in part by the situation they confront. Psychoanalysts have identified many defense mechanisms; they are usually discussed in relation to intrapsychic conflict. We believe that they are also applicable in interpersonal and other external conflict. We have space to discuss only a number of the important ones for understanding conflict with others (see Fenichel, 1945, and Freud, 1937, for fuller discussions):

- Denial occurs when it is too disturbing to recognize the existence of a conflict (as between husband and wife about their affection toward one another, so they deny it—repressing it so that it remains unconscious, or suppressing it so they do not think about it).

- Avoidance involves not facing the conflict, even when you are fully aware of it. To support avoidance, you develop ever-changing rationalizations for not facing the conflict (“I’m too tired,” “This is not the right timing,” “She’s not ready,” “It won’t do any good”).

- Projection allows denial of faults in yourself. It involves projecting or attributing your own faults to the other (“You’re too hostile,” “You don’t trust me,” “You’re to blame, not me,” “I’m attacking to prevent you from attacking me”). Suspicion, hostility, vulnerability, hypervigilance, and helplessness, as well as attacking or withdrawing from the potential attack of the other, are often associated with this defense.

- Projection allows denial of faults in yourself. It involves projecting or attributing your own faults to the other (“You’re too hostile,” “You don’t trust me,” “You’re to blame, not me,” “I’m attacking to prevent you from attacking me”). Suspicion, hostility, vulnerability, hypervigilance, and helplessness, as well as attacking or withdrawing from the potential attack of the other, are often associated with this defense.

- Reaction formation involves taking on the attributes and characteristics of the other with whom you are in conflict. The conflict is masked by agreement with or submission to the other by flattering and ingratiating yourself with the other. A child who likes to be messy but is anxious about her mother’s angry reactions may become excessively neat and finicky in a way that is annoying to her mother.

- Displacement involves changing the topic of the conflict or changing the party with whom you engage in conflict. Thus, if it is too painful to express openly your hurt and anger toward your spouse because he is not sufficiently affectionate, you may constantly attack him as being too stingy with money. If it is too dangerous to express your anger toward your exploitative boss, you may direct it at a subordinate who annoys you.

- Counterphobic defenses entail denial of anxiety about conflict by aggressively seeking it out—by being confrontational, challenging, or having a chip on your shoulder.

- Escalation of the importance of the conflict is a complex mechanism that entails narcissistic self-focus on your own needs with inattention to the other’s needs, histrionic intensity of emotional expressiveness and calling attention to yourself, and demanding needfulness. The needs involved in the conflict become life-or-death issues, the emotions expressed are intense, and the other person must give in. The function of this defense is to get the other to feel that your urgent needs must have highest priority.

- In intellectualization and minimization of the importance of the conflict, you do not feel the intensity of your needs intellectually but instead experience the conflict with little emotion. You focus on details and side issues, making the central issue from your perspective in the conflict seem unimportant to yourself and the other.

The psychoanalytical emphasis on intrapsychic conflict, anxiety, and defense mechanisms highlights the importance of understanding the interplay between internal conflict and the external conflict with another. Thus, if an external conflict elicits anxiety and defensiveness, the anxious party is likely to project onto, transfer, or attribute to the other characteristics similar to those of internalized significant others who in the past elicited similar anxiety in unresolved earlier conflict. Similarly, the anxious party may unconsciously attribute to himself the characteristics he had in the earlier conflict. Thus, if you are made very anxious by a conflict with a supervisor (you feel your basic security is threatened), you may distort your perception of the supervisor and what she is saying so that you unconsciously experience the conflict as similar to unresolved conflict between your mother and yourself as a child.

If you or the other is acting defensively, it is important to understand what is making you or her anxious, what threat is being experienced. The sense of threat, anxiety, and defensiveness hampers developing a productive and cooperative problem-solving orientation toward the conflict. Similarly, transference reactions—for example, reacting to the other as though she were similar to your parent—produces a distorted perception of the other and interferes with realistic, effective problem solving. You can sometimes tell when the other is projecting a false image onto you by your own countertransference reaction: you feel that she is attempting to induce you to enact a role that feels inappropriate in your interactions with her. You can sometimes become aware of projecting a false image onto the other by recognizing that other people do not see her this way or that you are defensive and anxious in your response to her with no apparent justification.

Irrational Deterrents to Negotiation.

There are many reasons that otherwise intelligent and sane individuals may persist in behaviors that perpetuate a destructive conflict harmful to their rational interests. Following are some of the common reasons

- Perpetuating the conflict enables one to blame one’s own inadequacies, difficulties, and problems on the other so that one can avoid confronting the necessity of changing oneself. Thus, in the couple I (M.D.) treated (see the Introduction to this Handbook), the wife perceived herself to be a victim and felt that her failure to achieve her professional goals was due to her husband’s unfair treatment of her as exemplified by his unwillingness to share responsibilities for the household and child care. Blaming her husband provided her with a means of avoiding her own apprehensions about whether she personally had the abilities and courage to fulfill her aspirations. Similarly, the husband who provoked continuous criticism from his wife for his domineering, imperious behavior employed criticisms to justify his emotional withdrawal, thus enabling him to avoid dealing with his anxieties about personal intimacy and emotional closeness. Even though the wife’s accusations concerning her husband’s behavior were largely correct, as were the husband’s toward her, each had an investment in maintaining the other’s noxious behavior because of the defensive self-justifications such behavior provided.

- Perpetuating the conflict enables one to maintain and enjoy skills, attitudes, roles, resources, and investments that one has developed and built up during the course of one’s history. The wife’s role as “victim” and the husband’s role as “unappreciated emperor” had long histories. They had well-honed skills and attitudes in relation to their respective roles that made their roles very familiar and natural to enact in times of stress. Less familiar roles, in which one’s skills and attitudes are not well developed, are often avoided because of the fear of facing the unknown. Analogous to similar social institutions, these personality institutions also seek out opportunities for exercise and self-justification, and in so doing they help to maintain and perpetuate themselves.

- Perpetuating the conflict enables one to have a sense of excitement, purpose, coherence, and unity that is otherwise lacking in one’s life. Some people feel aimless, dissatisfied, at odds with themselves, bored, unfocused, and unenergetic. Conflict, especially if it has dangerous undertones, can serve to counteract these feelings: it can give a heightened sense of purpose as well as unity and can also be energizing as one mobilizes oneself for struggle against the other. For depressed people who lack self-esteem, conflict can be an addictive stimulant to mask an underlying depression.

- Perpetuating the conflict enables one to obtain support and approval from interested third parties. Friends and relatives on each side may buttress the opposing positions of the conflicting parties with moral, material, and ideological support. For the conflicting parties, changing their positions and behaviors may entail the dangers of loss of esteem, rejection, and even attack from others who are vitally significant to them.

How does a therapist or other third party help the conflicting parties overcome such deterrents to recognizing that their bitter, stalemated conflict no longer serves their real interests? The general answer, which is quite often difficult to implement in practice, is to help each of the conflicting parties change in such a way that the conflict is no longer maintained by conditions in the parties that are extrinsic to the conflict. In essence, this entails helping each of the conflicting parties to achieve the self-esteem and self-image that would make them no longer need the destructive conflict process as a defense against their sense of personal inadequacy, their fear of taking on new and unfamiliar roles, their feeling of purposelessness and boredom, and their fears of rejection and attack if they act independently of others. Fortunately the strength of the irrational factors binding the conflicting parties to a destructive conflict process is often considerably weaker than the motivation arising from the real havoc and distress resulting from the conflict. Emphasis on this reality, if combined with a sense of hope that the situation can be changed for the better, provides a good basis for negotiation.

Summary and Critique of the Psychodynamic Approach.

We have not attempted to present an exposition of the specific theories of the many contributors to the development of psychoanalytical theory, from Freud to today. Rather, we seek to draw from these theories some of the major ideas that are useful to conflict practitioners and that can be briefly presented.

Psychoanalysis has been criticized, particularly the earlier Freudian version, which no longer seems appropriate in light of the changes made by later theorists: it is too biologically deterministic, too sexist, too pessimistic, and too focused on sex and aggression as the motives of behavior, as well as not oriented at all to positive motivations, to the learning and development of cognitive functions or to the broader societal and cultural determinants of personality development. Nevertheless, it is a useful framework for understanding issues that we all confront during development (security, control and power, sexual identity, transformation from childhood to adulthood) and the problems and personality residues that may result from inadequate care and harsh circumstances during our early years.

The discussion of psychodynamics in this section has focused on the psychodynamics of individuals in conflict situations. However, psychodynamic theory has also been used to throw light on issues of war and peace (Gratch, 2012), the Arab-Israeli conflict (Falk, 2004), international relations (Volkan, 1988, 2009), the rise of fascism (Reich, 1946), Hitler’s ideology (Koenigsberg, 1975), as well as on many other topics related to conflict.

Psychoanalysis is not a scientific theory that was developed and tested in a scientific laboratory, as is the case for most of the theories presented elsewhere in this Handbook. Rather, it is a mosaic of subtheories mainly developed in clinically treating psychopathology. Many of its concepts are not defined so as to indicate how they can be observed and measured. It is instead an encompassing intellectual framework for thinking about personality and its development, one that has given rise to a variety of useful subtheories and ideas, many of which are testable and indeed have been tested in research.

Need Theories

Under this heading, we consider some of the ideas of Henry A. Murray and Abraham Maslow, the most influential of the need theorists.

Murray’s Need Theory of Personality.

Murray’s approach to personality was influenced by the work of Jung, Freud, and their successors, and he was one of the first psychologists to translate psychodynamic concepts and ideas into testable hypotheses. Unlike their concern with the abnormal, Murray’s focus was on the normal personality. The most distinctive feature of his theory is its complex system of motivational concepts. In his theory, needs arise not only from internal processes but also from environmental forces.

Murray’s most influential contribution to personality theory is the concept of the individual as a striving, seeking being: his orientation reflects primarily a motivational psychology. As he wrote, “The most important thing to discover about an individual . . . is the superordinate directionality (or directionalities) of his activities, whether mental, verbal, or physical” (1951, p. 276). This concern with directionality led him to develop the most complete taxonomy of needs ever created.

Need is a force in the brain region that organizes perception, thought, and action so as to change an existing unsatisfactory condition. Needs can be evoked by environmental as well as internal processes. They vary in strength from person to person and from situation to situation. Murray hypothesized the existence of about two dozen needs and characterized them in some detail. He insisted that adequate understanding of human motivation must incorporate a sufficiently large number of variables to reflect, at least in part, the tremendous complexity of human motives.

Working from Murray’s theory, McClelland and his colleagues (McClelland, Atkinson, Clark, and Lowell, 1953; McClelland, 1971) did extensive research on four basic needs: achievement, affiliation, power, and autonomy. Those high in need of achievement are concerned with improving their performance, do best on a moderately challenging task, prefer personal responsibility, and seek performance feedback. Persons rated high in the need for affiliation are concerned with maintaining or repairing relationships, are rewarded by being with friends, and seek approval from friends and strangers. Those in need of power are concerned with their reputation and find themselves motivated in a situation presenting hierarchical conditions. In their desire to attain prestige, they are likely to engage in competition more than the other types do. Finally, those with high autonomy needs want to be independent, unattached, and free of restraint.

Murray’s theory is a rich and complex view of personality. It can help practitioners become aware of the diversity of human needs and their expression, as well as the external circumstances that tend to evoke them and the childhood experiences that lead individuals to varied life striving. Its major deficiency is the lack of a well-defined learning and developmental theory of what determines the acquisition and strength of an individual’s needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Although Abraham Maslow, early in his professional career, coauthored an excellent textbook on abnormal psychology with a psychoanalyst, he came to feel that a psychology based on the study of the abnormal was bound to give a pessimistic, limited view of the human personality and not take into account altruism, love, joy, truth, justice, beauty, and other positive features of human life. Maslow was one of the founders of the humanistic school of psychology, which emphasizes the positive aspects of human nature.

Maslow is best known for his postulation of a hierarchy of human needs (Maslow, 1954); our discussion in this chapter is limited to this area of his work. In order of priority, he identified five types of needs:

- Physiological needs —for air, water, and food and the need to maintain equilibrium in the blood and body tissues in relation to various substances and types of cell. Frustration of these needs leads to apathy, illness, and death.

- Safety needs —for security, freedom from fear and anxiety, shelter, protection from danger, order, and predictable satisfaction of one’s basic needs. Here, frustration leads to fear, anxiety, rage, and psychosis.

- Belongingness and love needs —to be part of a group (a family, a circle of friends), to feel cared for, to care for others, to be intimate with another, and so forth. Frustration of these needs produces alienation, loneliness, and various forms of neurosis.

- Esteem needs —for self-esteem (self-confidence, mastery, worth, strength, and the like) and social esteem (respect, dignity, appreciation, and so on). Feelings of inadequacy, inferiority, helplessness, incompetence, shame, guilt, and the like are associated with frustration in this category.

- Self-actualization needs— to achieve one’s full potential in relation to others, in developing one’s own talents, and in taking part in one’s community (includes metaneeds such as truth, justice, beauty, curiosity, and playfulness). Frustration of the self-actualization need leads to restlessness, depression, and loss of zest in life.

Maslow considered the first four on this list to be deficiency needs, arising from a lack of what a person needs. Once these basic needs are all reasonably satisfied, we get in touch with our needs for self-actualization and pursue their satisfaction. Although Maslow initially postulated needs as hierarchically ordered, he later accepted the view that in reality, some people violate the hierarchy—say, putting themselves in danger and going hungry to protect someone they love or a group with which they identify.

One interesting, albeit controversial, perspective on Maslow’s theory queries the function of hierarchical order, particularly in relation to applying the definition of self-transcendence to negative consequences, or “negative” self-transcendence (Fields, 2004; Koltko-Rivera, 2006). If self-transcendence is defined as surrendering one’s personal needs to a cause beyond the self or a greater good, then these theorists ask whether we should include not only Gandhi but also suicide terrorists as self-transcendent individuals. This speculation brings up the question of order in Maslow’s theory: suicide terrorists are often young and would appear unlikely to have successfully completed the lower motivational levels in the hierarchy. Koltko highlights the need for further exploration concerning individuals who step out of sequence in fulfilling Maslow’s needs and questions whether this leads to a negative pole of self-transcendence.

Maslow’s theory, or a variation of it, is the foundation of the “human needs” theory of John Burton (1990) and his colleagues and students. The fundamental thesis of this approach is that a conflict is not resolved constructively unless the parties’ basic human needs are brought out and dealt with to the satisfaction of each party. The application of this idea to conflict is called the “problem-solving workshop.” Burton initially developed it while he was serving as a consultant to the conflict in Cyprus between the Greeks and the Turks; subsequently, it was systematically developed by Kelman (1986) and his colleagues. It entails creating conditions that enable the participants to express their real needs openly and honestly, and then try to work out a resolution that meets the basic needs of both sides. (See also mention of this in chapter 10.)

Social Learning Theory

In Bandura’s interactionist perspective on personality (Bandura, 1986), the individual is a thinking person who can impose some direction on the forces from within and the pressures from the external environment. Bandura asserts that behavior is a function of a person in her environment: cognition, other personal traits, and the environment mutually influence one another. People learn by observing the behavior of others and the different consequences attending these behaviors. Learning requires that the person be aware of appropriate responses and value the consequences of the behavior in question.

Unlike a number of other theorists, Bandura does not believe that aggression is innate. Through imitation of social models, people learn aggression, altruism, and other forms of social behavior as well as constructive and destructive ways of dealing with conflict. The ability to imitate another’s behavior depends on the characteristics of the model (whether or not the model makes her behavior unambiguous and clearly observable), the attention of the observer (whether or not the observer is sharply focused on the model’s behavior), memory processes (whether or not the observer is intelligent and able to recall what has been observed), and behavior capabilities (whether or not the observer has the physical and intellectual capability to reproduce the behavior observed).

Assuming that one has the capability, readiness to reproduce the behavior of the model is determined by factors such as whether the model has been perceived to obtain positive or negative consequences as a result of behavior, the attractiveness and power of the model, the vividness of behavior, and the intrinsic attractiveness of behavior that has been modeled. Thus, a boy may be predisposed to engage in aggressive behavior (using a handgun to threaten a rival) if he has seen a prestigious older figure (his father, older brother, a group leader, a movie star) engage in such behavior and feel good about doing so. Access to a handgun ensures that the boy has the capability of acting on his aggressive predisposition.

Developing a sense of self-efficacy or confidence in these competencies requires one to (1) use these skills to master tasks and overcome the obstacles posed by the environment, (2) cultivate belief in the capacity to use one’s competencies effectively, and (3) identify realistic goals and opportunities to use one’s skills effectively. Realistic encouragement to achieve an ambitious but attainable goal promotes successful experience, which aids in developing the sense of self-efficacy; social prodding to achieve unattainable goals often produces a sense of failure and undermines self-efficacy.

We selectively emphasize Bandura’s concepts of observational learning and self-efficacy because of their relevance to conflict. Given that most people acquire their knowledge, attitudes, and skills in managing conflict through observational learning, some people have inadequate knowledge, inappropriate attitudes, and poor skills for resolving their conflicts constructively while others are better prepared to do so. It is very much a function of the models they have been exposed to in their families, school, communities, and the media. It is our impression that many people have been exposed to poor models. When this is the case, making changes in the ways they handle conflict requires relearning, a process involving commitment and effort.

Relearning involves helping people become fully aware of how they currently behave in conflict situations, exposing them to models of constructive behavior, and extending repeated opportunities in various situations to enact and be rewarded for constructive behavior. In the course of relearning, people should become uncomfortable and dissatisfied with their old, ineffective ways of managing conflict so that they may develop a sense of self-efficacy in new, constructive methods of conflict resolution.

Social Situations and Psychological Orientations

Although Deutsch is not classified as a personality theorist, his concept of situationally linked psychological orientations is a useful and somewhat different perspective. He employs the term psychological orientation to refer to a more or less consistent complex of cognitive, motivational, and moral orientations to a given situation that serve to guide one’s behavior and response to a particular situation. He assumes that the causal arrow between psychological orientation and social situation is bidirectional; a given psychological orientation can lead to a given type of social relation or be induced by that type of social relation (Deutsch, 1982, 1985, 2012). With Wish and Kaplan (Wish, Deutsch, and Kaplan, 1976), he identified five basic dimensions of interpersonal relations:

- Cooperation-competition . Social relations such as “close friends,” “teammates,” and “coworkers” are usually on the cooperative side of this dimension, while “enemies,” “political opponents,” and “rivals” are usually on the competitive side. See chapter 1 for further discussion.

- Power distribution (equal versus unequal) . “Business partners,” “business rivals,” and “close friends” are typically on the equal side, while “parent and child,” “teacher and student,” and “boss and employee” are on the unequal side. See chapter 6 for further discussion.

- Task oriented versus social-emotional . Interpersonal relations such as “lovers” and “close friends” are social-emotional, while “task force,” “negotiators,” and “business rivals” are task oriented.

- Formal versus informal . Relations with a bureaucracy tend to be formal and regulated by externally determined social rules and conventions, while the relationship norms between intimates are informally determined by the participants.

- Intensity and importance . This dimension has to do with the intensity or superficiality of the relationship. Important relationships, as between parent and child or between lovers, are on the important side, while unimportant relationships, as between casual acquaintances or between salesperson and customer, are on the superficial side.

The character of a given social relationship can be identified by locating it on all the dimensions. Thus, an intimate relationship between lovers is typically characterized in the United States as relatively cooperative, equal, social-emotional, informal, and intense. Similarly, a sadomasochistic relationship between a bully and his victim is usually identified as competitive, unequal, social-emotional, informal, and intense. Deutsch indicates that a distinctive psychological orientation is associated with the particular location of a social relationship along the five dimensions. Positing that there are three components of a psychological orientation that are mutually consistent, he describes them as follows:

- Cognitive orientation consists of structured expectations about oneself, the social environment, and the people involved. This makes it possible for one to interpret and respond quickly to what is going on in a specific situation. If your expectation leads to inappropriate interpretation and response, then you will likely revise that expectation. Or if the circumstances confronting you are sufficiently malleable, your interpretation and response to them may help to shape their form. Thus, what you expect to happen in a situation involving negotiations about your salary with your boss is likely to be quite different from what you expect in a situation in which you and your spouse are making love.

- Motivational orientation alerts one to the possibility that in the situation, certain types of need may be gratified or frustrated. It orients you to questions such as, “What do I want here, and how do I get it?” “What is to be valued or feared in this relationship?” In a business negotiation, you are oriented to the satisfaction of financial needs, not affection; in a love relationship, the opposite is true.

- Moral orientation focuses on the mutual obligations, rights, and entitlements of the people involved in the relationship. It implies that in a relationship you and the other mutually perceive the obligations you have to one another and mutually respect the framework of social norms that define what is fair or unfair in the interactions and outcomes of everyone involved.

To illustrate Deutsch’s ideas, we contrast the psychological orientations in two relations: friend-friend and police officer–thief. For practical purposes, we limit our discussion of the cooperative-competitive, power, and task-oriented versus social emotional dimensions.

Friends have a cooperative cognitive orientation: “we are for one another.” The motivational orientation is of affection, affiliation, and trust, and the moral orientation is one of mutual benevolence, respect, and equality. In contrast, the police officer and thief have a competitive cognitive orientation (what’s good for the other is bad for me); the motivational orientation is of hostility, suspicion, and aggressiveness or defensiveness; the moral orientation involved is that of a win-lose struggle to be conducted under either fair rules or a no-holds-barred one in which any means to defeat the other can be employed.

Friends are of equal power and employ their power cooperatively. Their cognitive orientation to power and influence relies on its positive forms (persuasion, benefit, legitimate power); their motivational orientation supports mutual esteem, respect, and status for both parties; their moral orientation is that of egalitarianism. In contrast, the police officer and thief are of unequal power. The officer is cognitively oriented toward using negative forms of power (coercion and harm), with a motivational orientation to dominate, command, and control. Morally, the officer feels superior and ready to exclude the thief from the former’s moral community (those who are entitled to care and justice). In cognitive response to the low-power position, the thief either tries to improve power relative to the police officer or submits to the role as one who is under the officer’s control. Thus, the thief’s motivational orientation may be rebellious and resistant (expressing the need for autonomy and inferiority avoidance) or passive and submissive (expressing the need for abasement). This moral orientation is either to exclude the officer from the thief’s own moral community or to “identify with the aggressor” (Freud, 1937), adopting the moral authority of the more powerful for oneself.

Friends have a social-emotional orientation, while the police officer and thief have a task-oriented relationship to one another. In the latter, one is cognitively oriented to making decisions about which means are most efficient in achieving one’s ends; the task-oriented relationship requires an analytical attitude to compare the effectiveness of various means. One is oriented to the other impersonally as an instrument to achieve one’s ends. The motivational orientation evoked by a task-oriented relationship is that of achievement, and the moral orientation toward the other is utilitarian. In contrast, friends have a cognitive orientation in which the unique personal qualities and identity of the other are of paramount importance. Motivations characteristic of such relations include affiliation, affection, esteem, play, and nurturance-succorance. The moral obligation to a friend is to esteem the other as a person and help when the other is in need.

Deutsch’s view of the relation between social situation and psychological orientation is not only that a particular situation induces a particular psychological orientation, but also that individuals vary in their psychological orientation and personality. Based on their life experiences, some people tend to be cooperative, egalitarian, and social-emotional in their orientation, while others tend to be competitive, power seeking, and task oriented. For example, in many cultures, women, compared to men, tend to have relatively strong orientations of the former type (cooperative and so on), while men have relatively stronger orientations of the latter (competitive) type.

Personality disposition influences the choice of social situations and the social relations that one seeks out or avoids. Given the opportunity, people select social relations and situations that are most compatible with their dominant psychological orientations. They also seek to alter or leave a social relation or situation if it is incompatible with their disposition. If this is impossible, they employ the alternative, latent psychological orientations within themselves that are compatible with the social situation.

Knowledge of the dimensions of social relations can be helpful to a conflict practitioner in analyzing both the characteristics of a situation and the psychological orientations the parties are likely to display in the circumstances. It is also useful in characterizing individuals in terms of their dominant psychological orientations to social situations. It should be noted, however, that Deutsch’s ideas are not well specified about what happens if the individual’s disposition and the situational requirements are incompatible.

TRAIT APPROACHES

The second major approach to the study of personality is the nomothetic, exemplified by trait research and its application to behavior. Traits can be defined as words summarizing a set of behaviors or describing a consistent response to relationships and situations as measured through an assessment instrument (Martin, 1988). It is assumed that in well-designed and tested assessment instruments, many individuals can validly report social-emotional responses and behaviors that are broadly consistent across situations (some characteristics are less stable across situations than others). Measurement of individual characteristics is widespread and has proven to be quite useful in a number of situations, as when a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist diagnoses a patient and prescribes treatment based on the results of a battery of trait-assessment instruments in addition to a diagnostic interview. Research studies frequently use personality measures to predict behavior under designated situational constraints. Personality assessment may also be extremely useful in placing children or adults in the most effective educational settings or identifying a cognitive mediator that affects behavior, such as an individual’s attribution of intentionality as a reaction to imagined hostility from another.

Because our interests center on multitrait measurement, we briefly mention single-trait approaches and refer readers to other sources for in-depth discussion. The single-trait approach to studying conflict process and outcome seeks to understand social behavior in terms of relatively stable traits or dispositions residing within the individual; it is now considered to have limited usefulness. The trait approach typically focuses on one or more enduring predispositions of specific types: motivational tendencies (aggression, power, pride, fear), character traits (authoritarianism, Machiavellianism, locus of control, dogmatism), cognitive tendencies (cognitive simplicity versus complexity, open versus closed mind), values and ideologies, self-conceptions and bases of self-esteem, and learned habits and skills of coping. (See Bell and Blakeney, 1977; Neale and Bazerman, 1983; Rotter, 1980; and Stevens, Bavetta, and Gist, 1993, for discussions of some single-trait measures.)

The now-dominant approach to explaining social behavior is one that seeks to understand its regularity in terms of the interacting and reciprocally influencing contribution of both situational and dispositional determinants. There are several well-supported propositions in this approach:

- Individuals vary considerably in terms of whether they manifest consistency of personality in their social behavior across situations—for example, those who monitor and regulate their behavioral choices on the basis of situational information show relatively little consistency (Snyder and Ickes, 1985).

- Some situations have strong characteristics, in which little individual variation in behavior occurs despite differences in individual traits (Mischel, 1977).

- A situation can evoke dispositions because of their apparent relevance to it; subsequently, the situation becomes salient as a guide to behavior and permits modes of behaving that are differentially responsive to individual differences (Bem and Lenney, 1976).

- A situation can evoke self-focusing tendencies that make predispositions salient to the self, and as a consequence, these predispositions can become influential determinants of behavior in situations where such a self-focus is not evoked.

- There is a tendency for congruence between personal disposition and situational characteristics (Deutsch, 1982, 1985) such that someone with a given disposition tends to seek out the type of social situation that fits the disposition; people tend to mold their dispositions to fit a situation that they find difficult to leave or alter. That is, the causal arrow goes both ways between situational characteristics and personality disposition.

Multitrait Measures of Personality and Conflict

Given the importance of creating clearer definitions and comprehensive measures of personality, a number of researchers have worked to develop reliable multidimensional personality assessment instruments. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to present an overview of these instruments; however, we describe what has become a fundamental model of adult personality (Antonioni, 1998; Digman, 1990).

The Five-Factor Model.

In an attempt to describe personality more completely than is afforded by individual traits, Costa and McCrae (1985) developed the five-factor model (FFM) of personality, composed of five independent dimensions: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. Although there has recently been research conducted to show that the theory is applicable to young children (Grist and McCord, 2010; Grist, Socha, and McCord, 2012) as well, we concentrate on the adult personality in this chapter:

- Neuroticism . This is a tendency to experience unpleasant emotions. It encompasses six subscales: anxiety, hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsiveness, and vulnerability (e.g., panic in emergencies). People with strong neurotic tendencies are thought to be less able to control their emotions and cope effectively with stress (Costa and McCrae, 1985). With respect to interpersonal conflict, individuals high in levels of angry hostility, depression, vulnerability, and self-consciousness might find conflict threatening, prompting them to avoid conflict situations or to use contentious tactics as a reaction to the threat. People with low neurotic tendencies would be less likely to interpret the situation in terms of their own emotional distortion and perhaps use more constructive strategies.

- Extraversion . Differences in the desire for social activity are incorporated in this scale, which includes interpersonal traits such as warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement seeking, and interest in other people. Although extraverts are motivated by both affiliation and social dominance, it has been suggested that during conflict, the extravert’s motives for dominance may be stronger than the desire for communion (Bono, Boles, Judge, and Lauver, 2002). Accordingly, an individual’s scoring on specific extraversion facets (warmth, assertiveness, and so on) may be indicative of the conflict goals (social dominance or affiliation) most likely to be pursued during a conflict episode.

- Openness . Openness to experience denotes receptiveness to ideas and experiences, with subscales of openness to fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, actions, ideas, and values. This trait is thought to involve intellectual activity, originality, a need for variety and novel experiences, and cognitive complexity. With respect to conflict situations, one would expect open individuals to prefer strategies that involve flexibility, generation of alternatives, and consideration of the other’s view—strategies used in direct, constructive negotiation. Closed individuals tend to emphasize order and conformity and a need for closure. They are less flexible and have more difficulty understanding others’ points of view. Closed individuals find unresolved conflict upsetting and prefer an efficient, quick solution, perhaps being more likely to impose their own resolution.

- Conscientiousness . This dimension refers to achievement striving, competence, and self-discipline. Those low on this scale may be disorganized or lazy, negligent, and prone to quitting rather than persevering. Those on the high end of this dimension are well prepared and well organized, and they strive for excellence. Given these characteristics, those high in conscientiousness might be expected to prefer dealing with conflict directly, where low scorers might be expected to either use attacking strategies or avoid conflict situations altogether.

- Agreeableness . This refers to persons who are trusting, generous, cooperative, lenient, good natured, and sympathetic to others’ needs. High agreeableness leads individuals to have sympathy and concern for others, but it also may inhibit assertiveness or cause them to defer to others. In a conflict situation, this may result in decisions that fail to meet their own best interests. Overall, those who score high on such facets as trust, altruism, and compliance would be expected to use constructive strategies such as negotiation and to be concerned with interpersonal relationships. Low scorers are suspicious, antagonistic, critical, irritable, and self-centered. These individuals are prone to express anger in conflict situations, to be guarded in expressing their own feelings, and to compete rather than cooperate with other people. Research indicates that low scorers experience conflict more frequently (Suls, Martin, and David, 1998).

The FFM dimensions have been reliably demonstrated to occur in an impressive number of groups, including children, women and men, nonwhite and white respondents, and people from such varied linguistic and cultural backgrounds as Dutch, German, Japanese, Chinese, and Filipino. Furthermore, the personality trait constructs of the FFM reflect many of the personality categories used in psychotherapy, the difference being that the FFM dimensions are more testable in research and cover a broader range of human behavior than the attributes of personality emerging from the study of psychopathology.

We focus on the five-factor trait model to offer information for conflict resolution because it is

- More comprehensive than other trait models of personality in incorporating a wide range of human response and behavior. Most other inventories can be subsumed within its dimensions.

- Inclusive of normal behaviors as well as the extremes to be found in personality disorders.

- A robust measure of personality that has been validated in a variety of languages and cultures.

- A personality approach that is straightforward, fairly easily understood, and one of the dominant models of personality used in current research (Park and Antonioni, 2007; Grist and McCord, 2010; Jensen-Campbell, Gleason, Adams, and Malcolm, 2003; Moberg, 2001; Sibley and Duckitt, 2008; Wood and Bell, 2008).

Obviously, nonpersonality factors such as cognitive distortion, dysfunctional belief, personal evaluation, intelligence, and situational demands need to be examined along with the five personality factors to fully account for behavior. However, dismissing the multitrait approach would be to lose sight of its merit for use by laypersons without an advanced degree in personality psychology or psychotherapy. In methodologically appropriate use, the FFM appears to offer valuable information about the conflict resolution process for practitioners, as we discuss below.

Measures of Conflict Style.

A number of similar approaches to measuring individual styles of managing conflict have been developed (Blake and Mouton, 1964; Kilmann and Thomas, 1977; Rahim, 1986; Thomas, 1988). Although the early model of Kilmann and Thomas was named “the MODE,” these models are now commonly called “dual concern models” (Rubin, Pruitt, and Kim, 1994). They have their origins in Blake and Mouton’s two-dimensional managerial grid, in which a manager’s style was characterized in terms of the two separate dimensions of having a concern for people and a concern for production of results.

The dimensions in the dual-concern model of conflict style are concern about others’ outcomes and concern about own outcomes. High concern for the other as well as for oneself is linked to a collaborative problem-solving style. High concern for self and low concern for the other is connected with a contending, competitive approach. High concern for the other and low concern for the self is associated with yielding or submission. Low concern for both self and the other is associated with avoiding behavior.

Although additional work remains to be done on the measures of conflict style, it is likely that conflict behavior is determined by both situational and dispositional influences. Research by Rahim (1986) indicates that a manager in conflict with a supervisor resorts to yielding, while with peers, the manager employs compromising and with subordinates problem solving.

Personality and Conflict Resolution Strategies.

In research conducted by Sandy and Boardman (2006), 237 graduate students with no conflict resolution training experience were asked to fill out the NEO-PI-R FFM questionnaire (Costa and McCrae, 1985; Costa, McCrae, and Dye, 1991). Following this, subjects were asked to select three conflicts they had experienced during the previous three months. Each week for three successive weeks, they were given a comprehensive questionnaire and asked to describe one conflict (open-ended question) and report the strategies they used to handle it using both open-ended questions and the Kilmann and Thomas (1977) dual concerns model instrument. They also characterized their relationship with the other person in the conflict and, using five-point rating scales, indicated the size and importance of the conflict. In addition, they reported whether the conflict was resolved and whether the conflict strengthened or weakened their relationship.

The types of conflict reported included relationship issues (13 percent), another person’s failure to meet one’s own expectations (18 percent), discourteous or annoying behavior (16 percent), disagreements about what should be done (3 percent), one’s own failure to meet another’s expectations (6 percent), being offended by what another person said (14 percent), and displaced anger (15 percent). Conflicts were with relatives (17 percent), significant others (17 percent), friends (36 percent), acquaintances (12 percent), and people in the workplace, for example, bosses or subordinates (16 percent).

Factor and reliability analyses of the responses to the dual concerns instrument indicated that these subjects used four strategies for handling conflict, which we have labeled negotiation, contending, avoidance, and attack/blame. Negotiation consisted of strategies such as, “I sought a mutually beneficial solution,” and, “I tried to understand him or her.” Contending strategies included, “I used threats,” and, “I was sarcastic in my sense of humor.” Avoidance covered items such as, “I tried to change the subject,” and, “I denied there was any problem in the conflict.” Finally, attack/blame included, “I criticized an aspect of his or her personality,” and, “I blamed him or her for causing the conflict.”

Big Five Dimensions.

Negotiation Strategy.

Personality facet scales from the FFM dimensions formed predictive clusters of individual characteristics that tended to be associated with the dominant strategy used in the conflict reported. For example, those who used negotiation strategies scored high on agreeableness (particularly facets such as trust, altruism, and compliance). Conversely, they tended to score low on neuroticism (involving such facets as angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, and vulnerability).

The positive association between a collaborative conflict resolution strategy and the personality characteristic of agreeableness has also been found in other investigations of personality and conflict resolution style (Park and Antonioni, 2007; Bono et al., 2002; Wood and Bell, 2008). Speculation is that agreeable persons may be more likely to make positive attributions for behavior others might consider provocative (Graziano, Jensen-Campbell, and Hair, 1996) and also may experience more positive affect when engaging in cooperative actions.

Contending Strategy.

Personality facets influencing choice of a contending conflict resolution strategy include low scores on the conscientiousness domain (competence, duty, self-discipline, and deliberation); low scores on agreeableness (straightforwardness, trust, altruism, compliance and modesty); low scores on openness (ideas and values); and low scores on extraversion (warmth).

Higher scores on all the facets of the neuroticism domain were related to the choice of contending as a conflict resolution strategy. Other work in this area has found that neurotic individuals are more likely to employ attacking strategies or avoid conflicts altogether (Moberg, 2001). Such characteristics as impulsivity and emotional instability make the neurotic person more likely to attack the other person or, conversely, to avoid the conflict.

Avoidance Strategy.

Low scores on facets of the conscientiousness domain (competence, self-discipline, and order) and the extraversion domain (warmth, gregariousness, and assertiveness) are associated with people who use avoidance as a strategy for handling conflict. Avoidance is also used when individuals have higher scores on facets of neuroticism (angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, and vulnerability).

Attack Strategy.

Low scores on facets (competence, self-discipline, and order) of the conscientiousness domain are associated with the use of an attacking or blame type of behavior in conflict situations. The same is true for low scores on agreeableness facets (straightforwardness, trust, compliance, and tenderness) and the actions facet of the openness domain. High scores on facets of neuroticism (anxiety, angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, and vulnerability) are also associated with the use of attacking or blame to deal with conflict.

Situation versus Personality

Using a repeated measures analysis, we examined the influence of personality on consistency of conflict resolution strategy across situations or different conflicts described. Conflict resolution strategies were significantly different across situations, indicating that situational constraints were more influential in these cases in determining a conflict management approach.

Influences on Whether the Conflict Is Resolved

Importance of the Issue.

The importance of the conflict to the disputants played a significant role in whether the conflict was resolved. The more important the conflict was to the disputants, the less likely it was to be resolved.

Personality.

Individuals scoring higher on deliberation facets (conscientiousness), self-conscious and angry hostility (neuroticism), and feelings (openness) were less likely to have resolved their conflicts than those scoring in the lower group. Those scoring higher on warmth and assertiveness (extraversion) and actions (openness) were more likely to report their conflicts were resolved. What we do not know is whether their partners felt the conflict was resolved or found satisfaction in its resolution. It is likely that the attributions individuals make about any particular conflict episode are a function of their own personality, the personality of their partner, and salient factors of the situation.

Preferred Conflict Resolution Strategy

Those scoring higher on strategies such as attack, avoidance, and contending were less likely to have resolved the conflicts they described in the study. A negotiation strategy was significantly associated with resolved conflicts.

We note that the findings reported here are all statistically significant even though the correlations between personality facets and conflict behavior are low (mostly in that the ability to predict an individual’s conflict behavior from his personality measures is quite low). However, in the section that follows, we suggest that there are “difficult” or “extreme” personalities (which are relatively rare in the graduate student population that participated in this research) who are more likely to be consistent in their conflict behaviors in different situations.

Negotiating with Difficult Personalities

All too often, individuals have to negotiate with difficult people. It is often surprisingly easy to describe such individuals: people who are hostile, overly aggressive, or who explode emotionally; people who avoid conflict, avoid discussions, or resist by using passive-aggressive techniques; individuals who complain incessantly or blame others but never try to do anything about the conflict or situation; people who appear very agreeable but do not produce or follow through on what they propose; enervating, negative people who sap energy from others, claiming nothing will work and that there are no solutions; “superior” people who believe they know everything and are only too eager to tell you they do; and people who cannot make decisions, who stall, and who are indecisive (Bramson, 1981).

Drawing from past work on personality and conflict (Bramson, 1981; Heitler, 1980; Ury, 1993) as well as our own research, we offer some suggestions for coping with difficult people. As we discussed previously, the use of contentious tactics and blame is more often associated with people low in conscientiousness (e.g., self-discipline, deliberation, and competence), low in agreeableness (e.g., straightforwardness, trust, and altruism), and high in neuroticism (e.g., anxiety, angry hostility, depression, and impulsivity). Such angry, hostile people require special handling. First, it is useful to not react immediately to an attack: give the attacking party time to run down and regain emotional control. This is a critical first step, as well as difficult, because our natural tendency is to defend ourselves. William Ury (1993) calls this “going to the balcony” or choosing not to react. He describes imagining negotiating on stage and then climbing to the balcony overlooking the stage. The balcony is a metaphor for achieving a state of mental detachment necessary to arrive at constructive problem solving and regaining equilibrium. It is not useful to argue with someone who is attacking because she cannot “hear” you anyway and it only adds fuel to the fire. If the attack does not subside, it is helpful to say (or shout) a neutral word like, “Stop!” to break into her tantrum or take a break from the negotiation. Once the other has calmed down a bit, it is useful to state your opinions and perceptions calmly, facilitating the discussion by not arguing with her—as Ury calls it, “stepping to her side.” This means listening to her, acknowledging her feelings, and agreeing with her whenever possible to defuse negative emotions. Some hostile people, which Bramson (1981) called “snipers,” are slightly more subtle in their attacking behavior: they take potshots at you, making cutting remarks, or give you not-so-subtle digs. A helpful strategy in dealing with these people is to surface the attack, that is, do a process intervention by commenting on an observed behavior.

With respect to avoiding conflict, we found this strategy to be most often associated with low conscientiousness, low agreeableness, low extraversion, and high neuroticism. When trying to engage another who is avoiding conflict, a good strategy is to use open-ended questions and wait as calmly as you can for an answer. Many people rush to fill silences with conversation. Try to resist the temptation. If the person continues to avoid or remain silent, comment on what you are observing and end your comment with another open-ended question. If necessary, remind the other party of your resolve to solve the conflict to mutual satisfaction and try to pursue additional opportunities to engage in conversation.

Ury (1993) talks about “building a golden bridge” to help draw the other party in the direction you want him or her to move. This process has several steps: involving the other party in drafting the agreement; looking beyond obvious interests such as money to take into account more intangible needs, such as recognition or autonomy; helping the other save face as she backs away from an initial position. The last step could involve showing how circumstances may have changed since the beginning of the negotiation or using an agreed-on standard of fairness. You may want to proceed slowly and remember that it is important to note that addressing more intangible psychological needs is critical to the process of building a bridge.

CONCLUSION

In this chapter, we have presented several different approaches to understanding how personality may affect conflict behavior—one’s own behavior as well as that of the other with whom one is in conflict.

In brief, psychodynamic theories stress the view that conflict might induce anxiety, which is likely to lead to various forms of defensive behavior, which can disrupt the constructive resolution of conflict. This approach suggests that in a conflict, it is important to know what makes you anxious (your hot spots), when you are experiencing anxiety (your symptoms of anxiety), and the defensive behaviors you tend to engage in when you are anxious. Such knowledge will help you to control your anxiety and inhibit destructive, defensive behavior during a conflict. Also, this approach suggests that you understand that the other has hot spots, which you want to avoid, and that if the other seems defensive, you might try to reduce his anxiety level by adjusting behavior on your part to make the other feel more secure.

The need theories indicate that it is important to know what needs of yourself and the other are in conflict. Your needs as well as the needs of the other may not be well represented in the positions that are expressed. Learning how to understand the needs of the other as well as of oneself is an important conflict resolution skill that can be acquired. (See chapters 1 and 2 of this Handbook.) If the needs of the other, as well as one’s own, are not respected and addressed in a conflict agreement, the agreement is not likely to last.

Trait theories indicate that people who differ in personality traits also may systematically differ in their approach to conflict and their behavior during a conflict. Again, it is worth reiterating that for most people, situational factors (the social context, the power relation, and so on) are at least as important as personality traits in determining one’s conflict behavior. It is heartening to note that our own research and that of subsequent work by others have found consistent patterns in associations between personality and the choice of conflict resolution strategy. For example, there appears to be a reliable link between low conscientiousness, low agreeableness, and high neuroticism personality characteristics and the use of contentious tactics and avoidance strategies in conflict situations. Similarly, high agreeableness and low neuroticism is associated with negotiation and resolution of conflict. The value of being aware of one’s personality-driven behavior tendencies lies in the implication that through awareness, an individual can learn to control and modify inappropriate behavior for improved conflict outcomes. Continued research needs to focus on personality from the perspective of both parties in the conflict in relation to the dominant characteristics of the situation.

References

Antonioni, D. “Relationship between the Big-Five Personality Factors and Conflict Management.” International Journal of Conflict Management , 1998, 9 (4), 336–355.

Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Approach . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1986.

Bell, E. C., and Blakeney, R. N. “Personality Correlates of Conflict Resolution Modes.” Human Relations , 1977, 30 , 849–857.

Bem, S. L., and Lenney, E. “Sex Typing and the Avoidance of Cross-Sex Behavior.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 1976, 33 , 48–54.

Blake, R. R., and Mouton, J. S. The Managerial Grid . Houston, TX: Gulf, 1964.

Bono, J. E., Boles, T. L., Judge, T. A., and Lauver, K. J. “The Role of Personality in Task and Relationship Conflict.” Journal of Personality , 2002, 70 , 311–344.

Bramson, R. M. Coping with Difficult People . New York: Dell, 1981.

Burton, J. W. Conflict: Human Needs Theory . New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

Costa, P. T., Jr., and McCrae, R. R. The NEO Personality Inventory Manual . Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1985.

Costa, P. T., Jr., McCrae, R. R., and Dye, D. A. “Facet Scales for Agreeableness and Conscientiousness: A Revision of the NEO Personality Inventory.” Personality and Individual Differences , 1991, 12 , 887–898.

Deutsch, M. “Interdependence and Psychological Orientation.” In V. J. Derlaga and J. Grzelak (eds.), Cooperation and Helping Behavior: Theories and Research . Orlando, FL.: Academic Press, 1982.

Deutsch, M. Distributive Justice: A Social Psychological Perspective . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985.

Deutsch, M. A Theory of Cooperation-Competition and Beyond . In P.A.M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins (eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology (Vol. 2, 275–294). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012.

Digman, J. M. “Personality Structure: Emergence of the Five-Factor Model.” Annual Review of Psychology , 1990, 41 , 417–440.

Falk, A. Fratricide in the Holy Land: A Psychoanalytic View of the Arab-Israeli Conflict . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

Fenichel, O. The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis . New York: Norton, 1945.

Fields, R. M. “The Psychology and Sociology of Martyrdom.” In R. M. Fields (ed.), Martyrdom: The Psychology, Theology, and Politics of Self-Sacrifice . Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004.

Freud, A. The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence . London: Hogarth Press, 1937.

Gratch, A. “The Psychodynamics of Peace.” In P. T. Coleman and M. Deutsch (eds.), Psychological Components of Sustainable Peace (pp. 205–226). New York: Springer, 2012.

Graziano, W. G., Jensen-Campbell, L. A., and Hair, E. C. “Perceiving Interpersonal Conflict and Reacting to It: The Case for Agreeableness.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 1996, 70 , 820–835.

Grist, C. L., and McCord, D. M. “Individual Differences in Preschool Children: Temperament or Personality?” Infant and Child Development , 2010, 19 , 264–274.

Grist, C. L., Socha, A., and McCord, D. M. “The M5-PS-35: A Five-Factor Personality Questionnaire for Preschool Children.” Journal of Personality Assessment , 2012, 94 , 287–295.

Heitler, S. M. From Conflict to Resolution: Strategies for Diagnosis and Treatment of Distressed Individuals, Couples, and Families . New York: Norton, 1980.

Jensen-Campbell, L. A., Gleason, K. A., Adams, R., and Malcolm, K. T. “Interpersonal Conflict, Agreeableness, and Personality Development.” Journal of Personality , 2003, 71 , 1059–1085.

Kelman, H. C. “Interactive Problem Solving: A Social Psychological Approach to Conflict Resolution.” In W. Klassen (ed.), Dialogue toward Interfaith Understanding . Jerusalem: Ecumenical Institute for Theological Research, 1986.

Kilmann, R. H., and Thomas, K. W. “Developing a Forced-Choice Measure of Conflict Handling Behavior: The Mode Instrument.” Educational and Psychological Measurement , 1977, 37 , 309–325.

Koenigsberg, R. A. Hitler’s Ideology: A Study in Psychoanalytic Sociology . New York: Library of Science, 1975.

Koltko-Rivera, M. E. “Rediscovering the Later Version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Transcendence and Opportunities for Theory, Research, and Unification.” Review of General Psychology , 2006, 10 , 302–317.

Martin, R. P. Assessment of Personality and Behavior Problems: Infancy through Adolescence . New York: Guilford Press, 1988.

Maslow, A. H. Motivation and Personality . New York: Harper, 1954.

McClelland, D. C. Assessing Human Motiv ation. New York: General Learning Press, 1971.

McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., and Lowell, E. L. The Achievement Motive . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1953.

Mischel, W. “On the Future of Personality Measurement.” American Psychologist , 1977, 32 , 246–254.

Moberg, P. J. “Linking Conflict Strategy to the Five-Factor Model: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations.” International Journal of Conflict Management , 2001, 12 (1), 47–68.

Murray, H. A. Explorations in Personality . New York: Oxford University Press, 1951.

Neale, M. A., and Bazerman, M. H. “The Role of Perspective-Taking Ability in Negotiating under Different Forms of Arbitration.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review , 1983, 36 , 378–388.

Park, H., and Antonioni, D. “Personality, Reciprocity, and Strength of Conflict Resolution Strategy.” Journal of Research in Personality , 2007, 41 , 110–125.

Rahim, M. A. (ed.). Managing Conflict in Organizations . New York: Praeger, 1986.

Reich, W. (1946). The Mass Psychology of Fascism . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Rotter, J. B. “Interpersonal Trust, Trustworthiness, and Gullibility.” American Psychologist , 1980, 35 , 1–7.

Rubin, J. Z., Pruitt, D. G., and Kim, S. H. Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate, and Settlement . (2nd ed.) New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

Sandy, S. V., Boardman, S. K., and Deutsch, M. Personality and Conflict. In M. Deutsch, P. T. Coleman, and E. C. Marcus (eds.), The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice . (2nd ed.) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006.

Sibley, C. G., and Duckitt, J. “Personality and Prejudice: A Meta-Analysis and Theoretical Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review , 2008, 12 , 248–279.