CHAPTER NINETEEN

CREATIVITY AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION

a

The Role of Point of View

Howard E. Gruber

First conundrum: educators often view conflict as the problem child, the practitioner’s task as elimination of conflict. Students of creativity often view conflict as its necessary companion: (1) novelty engenders conflict and/or (2) creativity requires conflict.

Second conundrum: conflict resolution requires collaboration, if not as the goal then at least as the means. Creative work has been treated, by and large, as an individual effort, sometimes painfully isolated.

As an undergraduate at Brooklyn College, I learned from Solomon Asch, my teacher, about two interesting lines of research: his work on group pressures and his work with Witkin on frames of reference. Both of these bear on the issue of point of view, the major focus of this chapter. It has become clear to me, as to others, that an essential and almost omnipresent aspect of creative work is posing good questions. In studying Darwin’s notebooks and correspondence (Gruber, 1981), one sees that he gloried in discovering questions. He wrote many letters to scientists and naturalists around the world, posing challenging questions. His contemporaries were often mystified: Where did his questions come from? As a student, I adopted the position that having a novel point of view is the main thing. After all, among the contemporaries in question, then as now, were many good problem solvers—but where do their problems come from? Novel problems stem from a novel point of view. Then the central question becomes: How is a novel point of view constructed?

In his 1996 book, Human Judgment and Social Policy , Kenneth Hammond distinguishes between theories of truth, which center on the correspondence of ideas with facts, and theories that look inward for coherence of ideas with other ideas. The latter, coherence theories, do not offer definite procedures for making judgments and consequently must rely on wisdom and intuition. Correspondence theories do so provide, but in a world teeming with uncertainties, there is a triple price to be paid—which Hammond (1996) sums up beautifully in the subtitle of his book: Irreducible Uncertainty, Inevitable Error, Unavoidable Injustice . In both existing and historically experienced circumstances, this view casts a pretty dark shadow. My chosen topic, however, is not judgment but its necessary prelude, discovering or inventing the alternatives to be judged and among which to choose. Here, what is needed is not so much accuracy or logic but creative imagination and construction.

In this chapter, I give a brief account of the evolving systems approach to creative work, with special emphasis on point of view and social aspects of creativity. In addition, I explore some possible relations between creativity and conflict resolution, presenting experimental work with a “shadow box” designed to illuminate collaborative synthesis of disparate points of view.

EVOLVING SYSTEMS APPROACH

This approach is predicated on the uniqueness of each creative person as he or she moves through a series of commitments, problems, solutions, and transformations. These aspects of the creative process are not fixed, and they are not universal. Rather, they constantly evolve, and they differ from one creator to another. The system as a whole is composed of subsystems that are loosely coupled with each other. This looseness provokes the emergence of disequilibrium and the finding of new questions; consequently, it opens the way to unpredictable innovation.

Our task is to describe how a given creator actually works. It is not our task to measure the amount of creativity or to find factors that apply in the same way to all creators. What is necessary for one creative person confronting a problem may be unnecessary or even ill-advised for another.

The creative individual described here, interested in creativity in the moral domain, is only a first approximation. People who take responsibility want to make something happen. For this, they need allies, who must be persuaded, recruited, trained, and supported. Moreover, a full expression of morality would bring together moral thought, moral feeling, and moral action. Beyond these components, there must be creative integration. Although this last is rarely discussed, Donna Chirico has made an interesting effort in her integrative article, “Where Is the Wisdom? The Challenge of Moral Creativity at the Millennium” (1999). And of course, Erich Fromm’s whole oeuvre is a reflection on such a synthesis. (See Fromm, 1962, for example.)

In her case study of Niebuhr, Chirico shows how the quest for integration of thought, feeling, and action can lead to surprising results, can even go astray. She shows how Niebuhr achieved such an integration, but at a price. As he grew in influence, he gained new opportunities to move to the plane of moral action. But this brought him into collaborative interaction with a largely conservative establishment. In a series of such contacts, he became more conservative. Chirico (1999) writes, “As Niebuhr became involved increasingly in the political power structure as an insider, his radical views about the role of government shifted toward those of the authority figures he had previously denounced. Niebuhr moved from speaking as an independent thinker, whose ideology was informed by the Christian message, to acting as an advocate for the prevailing opinions of the United States government.”

Chirico stresses the difficulty, the need for the hard and steady work required, if we want to contribute to social transformation. She writes, “In a postmodern world where all is relative anyway, it is easier to accept inequity in the guise of personal or cultural differences than to take a moral stand . . . without moral creativity there can be no attempt. This involves self-sacrifice so that a community of concerned selves can come together and provoke change. It starts with taking a moral stand.”

Each creative case presents different aspects for study. These evolving opportunities may be grouped under three major headings: knowledge, purpose, and affect. All of them apply in the first instance to the creative individual at work. In addition, there are aspects that apply to the creator as a social being: social origins and development; relations with colleagues, mentorships, and so on.

Since each creative person is unique, if collaboration is needed, it must be collaboration among people who differ (in style, background, ability profile, and the like). Collaboration and similar relationships may take many forms: working together on a shared project where both members of a pair do work that is essentially the same (as Picasso and Braque did in inventing cubism); working together in a teamlike setting where participants complement each other (as in the production of a film, an opera, or a ballet); and sharing ideas either face-to-face or in written correspondence (as Vincent van Gogh and his brother, Theo, did through the medium of thousands of letters mostly about Vincent’s actual work, his plans for future work, and his sensuous experiences).

Networks of Enterprise

It is well established that creative work evolves over long periods of time. Some writers even speak of the ten-year rule. Whether this duration is two years or twenty or simply highly variable, it is certainly a far cry from the millisecond flashes vaunted by the devotees of sudden insight and mysterious intuition as the essence of creative effort.

If creative work takes so long, we must have an approach to motivation that recognizes the time it takes. I have found that one important aspect of creative work is the way each creator organizes a life so that diverse projects do not become obstacles to each other. I use the term enterprise to make room for the typical situation in which a person who completes one project does not abandon the line of work it entailed but picks up another that is part of the same set of concerns. I use the term network to accommodate the finding that creators are often simultaneously involved in several projects and enterprises linked to each other in complex ways.

Time and Irreality.

One of the most persistent myths about creative work is the allegation that novelty comes about through lightning-like flashes of insight. On the contrary, serious studies reveal accounts in which the time taken is on the order of years and decades. Even when a moment of sudden transformation occurs, it is the hard-won result of a long developmental process.

Engagement and commitment for such long periods of steady work require appropriate organization of the task space. On the one hand, the creator must fashion a network of enterprise that can withstand the challenges of distraction, fatigue, and failure. On the other hand, one of the chief instruments of creative persistence is a well-developed fantasy life: what cannot be done (yet) on the plane of reality is attainable in the world of dreams, fantasy, half-baked notebooks (Darwin), and private discussions (Einstein). Play becomes the midwife of creative change.

Play Ethic.

We teach and preach the work ethic, but from time to time the play ethic rears its head, especially among creators. But there is no inescapable conflict between work and play. There is fusion of work and play as well, as transformation of activity from playlike to worklike and vice versa, in an endless cycle.

Once we take account of this constructive, collective, perdurably patient character of creative work, it follows that some of the miasmal mystery surrounding thought about creativity can evaporate. To work together, people must communicate. For this, they must share a common language, which sometimes means that one must teach others the language to be shared. A striking example of this process is how the physicist Freeman Dyson deliberately set about working with Richard Feynman, bent on learning to understand “Feynman diagrams” so that he could teach the wider community of physicists to do likewise. (See Schweber, 1994.)

Extraordinary Moral Responsibility and Creativity in the Moral Domain

These are closely linked ideas. For the most part, research on moral development has been limited to the plane of judgment. When all that is required of the subject is to make a moral judgment, he or she is free to choose any position, from the mundane to the fanciful, from the craven to the courageous. But if morally guided conduct must follow from judgment, many, if not most, subjects disappear into the cracks. Indeed, these judgmental interstices are seen as normal and necessary for maintaining an orderly society. “Who will bell the cat?” is experienced as a threatening question.

The expression

is shorthand for a somewhat complex idea, to wit, that one “ought” to do some particular thing, or that there “ought to be a law” only makes sense if the predicated “ought” is possible. So “ought” implies “can.” But situations occur in which it is urgent to make the passage from “cannot” to “can” and where this can only be done by discovering and taking some new, unexplored path. This is when creative work becomes the moral imperative.

THE SHADOW BOX EXPERIMENTS

In Plato’s parable of the cave, the prisoners are chained to a single station and see nothing but shadows on the wall. They have no way of distancing or decentering themselves from this one limited view of the world. Limited and distorted as it may be, it is their reality. Plato’s point is that this is the normal situation of ordinary mortals, leaving them vulnerable to the distortions of group pressure. Sherif’s (1936) work on the formation of social norms and Asch’s (1952) work on group pressures have important points in common with the prisoners in Plato’s cave. The subjects in the experiments of both researchers are all looking at the scene to be judged in essentially the same way and from the same point of view. Thus, a difference in reports of what is seen must mean a disagreement. There is no opportunity for dialogue among the observers. The subjects are limited to looking and listening; they have no chance for an active exploratory or manipulative approach. Finally, the situation invites only judgment on a single variable, not the construction of a complex idea or object.

Under such conditions, intersubjective differences become disagreements that can be solved only by yielding, domination, and compromise—all of which occur.

In contrast, it is possible to imagine conditions in which observers have different information about the same reality but no need to disagree with each other. They may even be able to transcend their individual limitations and together arrive at a deeper grasp of the reality in question than would be possible for each alone. Our research grew out of the conviction that people can be vigorously truthful.

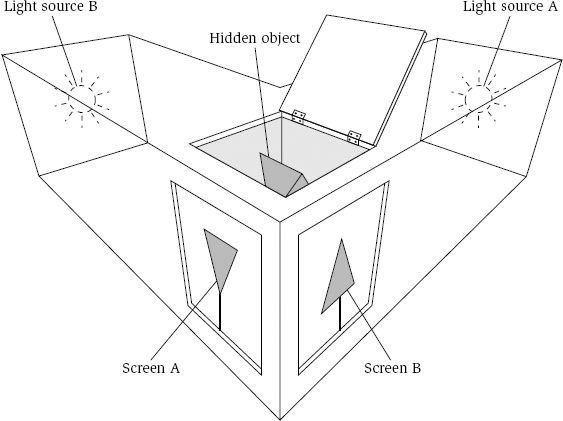

We have embodied this possibility in the microcosm of a shadow box. (See figure 19.1 .) In this arrangement, an object concealed in a box casts two differing shadows on two screens at right angles to each other. The subjects’ task is to discover the shape of the hidden object by discussing and synthesizing the two shadows of which each sees only one. Although our main interest was the process of collaboration of subjects with different viewpoints, to study that we also looked at the performance of single subjects shuttling back and forth between two screens.

Figure 19.1 The Shadow Box

Source: Gruber, H. E. “The Cooperative Synthesis of Disparate Points of View.” In I. Rock (ed.), The Legacy of Solomon Asch: Essays in Cognition and Social Psychology . Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1990. Reprinted with permission.

Note: The task is to use the two shadows to work out the shape of the hidden object.

Cooperative synthesis of such disparate points of view in the shadow box situation is not a simple matter. Each subject is asked to make an a priori assumption that the other participant’s observations represent the same entity. Each participant must convey what he or she sees clearly and correctly to the other. This may require inventing a suitable scheme for representing the information in question. When difficulties of communication arise, the problem of trusting the other must be dealt with. Often, too, the subjects must overcome a common tendency to ignore or underemphasize the other person’s contribution and to center attention on one’s own point of view.

When we compare one person shuttling between two station points with a pair of people, each of whom sees only one screen, sometimes the single person is superior and sometimes the pair. Over a wide range of situations, the individual perceptual apparatus is admirably organized for synthesizing disparate inputs: binocular vision, the kinetic depth effect, and all sorts of intermodal phenomena testify to the capability. However, there are at least some situations in which two heads are better than one.

From a practical point of view, the question of one head or two may not always be germane. There are real-world situations in which shuttling back and forth between station points is not feasible, so there must be an observer at each point. In negotiating situations, the number of heads is determined by sociopolitical realities. Going beyond the shadow box, the processes involved in cooperative synthesis of points of view are interesting in their own right.

Experiment One: Interaction of Social and Cognitive Factors

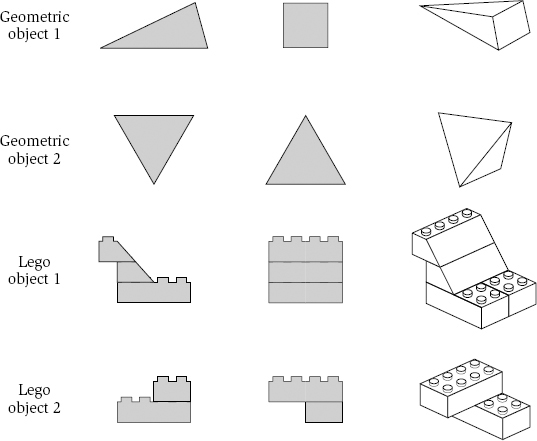

The subjects were first shown how the setup worked: two lamps, two screens, and a stalk on which to mount the object. (See Figure 19.1 .) They were shown how two shadows could be generated, one on each screen, and it was suggested to them that they could figure out what the object was by talking to each other or drawing pictures (material supplied). We compared subjects working in pairs with subjects working alone. In the pair situation, they were asked not to look at the other person’s screen. The subjects were children (ages seven to nine), adolescents (fourteen to sixteen), and adults (twenty to fifty-three). The pairs were asked to communicate with each other about what they saw and to work together to come to an agreement as to the shape of the concealed object that would account for the two shadows. Each single subject or each pair of subjects worked on two Lego objects and two geometrical objects, as shown in figure 19.2 .

Figure 19.2 Objects and Shadows in Experiment One: Geometrical Objects and Lego Objects

Source: Gruber, H. E. “The Cooperative Synthesis of Disparate Points of View.” In I. Rock (ed.), The Legacy of Solomon Asch: Essays in Cognition and Social Psychology . Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1990. Reprinted with permission.

The subjects almost invariably found the task challenging and interesting and worked on it for as long as an hour. Among children, the majority failed to solve (correctly synthesize) any of the objects; and among the adolescents and adults, there were a few who failed completely.

The main difference between adolescents and adults was that the latter often hit spontaneously on the idea that there might be more than one solution to a problem, sometimes even recognizing the possibility of an unlimited number of solutions. To our surprise, in a number of experiments, there was little difference in problem-solving success between singles and pairs. In only one respect was the pair condition clearly superior to the single: frequency of multiple solutions. This superiority was more pronounced in adult pairs than in adolescents.

Experiment Two: Comparison of Cooperative and Individualistic Orientations

Our goal was to examine the effect of social orientations within pairs on the synthesis of points of view. We used three kinds of instruction to the pairs. The cooperative instruction encouraged the pair to work together throughout the experiment, indicating that their performance would be evaluated as a pair compared with other pairs. The individualistic instruction asked the subjects to exchange information as to their respective shadows and then to work alone in solving the problem, indicating that their performance would be evaluated as individuals. The neutral instruction did not specify any mode of working together and did not mention evaluation. The subjects were twenty-four pairs of adolescents (ages fourteen to sixteen) and twenty-four pairs of adults (twenty-three to fifty-eight). There were no consistent or striking differences between the sexes, so that variable is ignored in this discussion.

Each pair was given a single problem, a tetrahedron fixed on an edge in such a position that each subject saw a triangular shadow, one with apex up, the other with apex down (see figure 19.1 ). We chose this rather difficult task to avoid the possibility that most subjects would solve the problem easily and to keep the subjects working long enough for us to make the observations we were interested in.

The resulting patterns of social behavior could be classified as individualistic, cooperative, or competitive. Subjects by no means followed the instructions we gave them. Surprisingly, among the adults the predominant behavior was cooperative, even when the instructions were neutral. Furthermore, even in the group given individualistic instructions, almost half the subjects were cooperative. It seemed as though the structure of the shadow box situation, presenting two perspectives bearing on a single object, naturally evoked cooperation as the appropriate response mode.

Most of the successful adult pairs were ones in which both members were cooperative. Moreover, in six of eight such pairs, the partners had different problem-solving strategies, one working mainly by adding planes and the other by constructing volumes. In exchanging information, the adults were more precise and detailed than the adolescents, giving information not only about shape but also about orientation, size, and position on the screen. The adults gave equal weight to both shadows, while the adolescents tended to focus on their own viewpoint. Adults were attentive to their partner’s suggestion, and they duly profited from their differences by improving the quality of their solutions and their comprehension of the tasks. The adolescents were less interested in the other’s ideas. They were also more concerned about whose solution was correct, as if only one were possible.

THE IMPORTANCE OF POINT OF VIEW

The importance of point of view emerges explicitly in many settings: Plato’s cave, the anthropologist’s relativism (which need not be despairingly total), postmodern nihilism, and so forth. Under conditions in which subjects are not able to explore and communicate freely, intersubjective differences become disagreements that are difficult to resolve. Techniques of conflict resolution that are successful under some conditions may lead only to fiasco in other circumstances, such as change in scale or change of mood. For example, sharing the commons requires civility and negotiation, and such conditions may sometimes be unattainable.

From our work with the shadow box, it becomes clear experimentally that under certain conditions taking the point of view of the other (POVO) is essential for collaborative work and that some problems absolutely require the synthesis of disparate points of view (POVOSYN). But such synthesis, like all creative work, is a delicate plant and may fail if conditions change.

The classic studies of conformity by Sherif (1936) and by Asch (1952) stemmed from rather different perspectives about the truth value of beliefs. Sherif thought that the development of social norms could be readily studied in a highly ambiguous stimulus situation, notably the autokinetic effect, and that this ambiguity corresponds well to real-world conditions. Asch objected to this image of human nature as passively yielding to group pressures; he believed that if confronted with clearly discriminable and unambiguous stimuli, observers would resist conformity.

Does the epistemology of the shadow box, especially recognizing multiple solutions, mean that anything goes, that we are no further than when we started in our quest for paths to truth? I think not. Even though there are multiple solutions, at least some are always excluded. The existence of multiple solutions does not open the way to unregulated relativism. To take only one example, a stationary cube can cast a variety of shadows, depending on its orientation, but it can never cast a circular shadow. By the same token, a stationary sphere can never cast a square shadow.

The importance of point of view is concisely expressed in a remark often attributed to Isaac Newton: “If I have seen farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants” (reported by Catherine Drinker Bowen in Merton, 1985). Merton’s book-length exploration of this aphorism is a pleasure to read. When all is said and done, a stationary sphere can never cast a square shadow.

References

Asch, S. E. Social Psychology . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1952.

Chirico, D. M. “Where Is the Wisdom? The Challenge of Moral Creativity at the Millennium.” Psychohistory , 1999, 27 , 47–58.

Fromm, E. Beyond the Chains of Illusion . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962.

Gruber, H. E. Darwin on Man: A Psychological Study of Scientific Creativity . (2nd ed.) Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Gruber, H. E. “The Cooperative Synthesis of Disparate Points of View.” In I. Rock (ed.), The Legacy of Solomon Asch: Essays in Cognition and Social Psychology . Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1990.

Hammond, K. R. Human Judgment and Social Policy: Irreducible Uncertainty, Inevitable Error, and Unavoidable Injustice . New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Merton, R. K. On the Shoulders of Giants: A Shandean Postscript . Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace, 1985.

Schweber, S. S. QED and the Men Who Made It . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Sherif, M. The Psychology of Social Norms . New York: HarperCollins, 1936.