CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

LEARNING THROUGH REFLECTION ON EXPERIENCE

An Adult Learning Framework for How to Handle Conflict

Victoria J. Marsick

Dorothy E. Weaver

Lyle Yorks

Conflict is endemic to modern life. As Thompson (2005) and numerous chapter authors in this Handbook recognize, when individuals seek to balance competing interests and build long-term and fair relationships, conflict resolution skills are enormously valuable—not just for negotiating practical issues, such as one’s salary, but also for the complicated and difficult conversations that pervade our lives (Stone and Patton, 2000). How do adults successfully learn to handle conflict? How do individuals learn to improve their negotiation skills?

In this chapter, we introduce a framework for learning to handle conflict that we call learning through reflection on experience , based on Marsick and Watkins’s model of informal and incidental learning (Cseh, Watkins, and Marsick, 1999; Marsick and Watkins, 1990; Watkins and Marsick, 1993) which in turn is informed by Dewey (1938), Mezirow (1991), and Argyris and Schön (1974, 1978).

We begin by discussing the roots of the framework in adult learning theory and draw out implications for its use in the teaching—and learning—of conflict resolution using examples, some drawn from one author’s research (Weaver, 2011). We illustrate ways in which those involved in conflict can use reflection to handle challenging situations—whether before a conflict is negotiated, during a heated or difficult event, or after a conflict—and enhance learning. Finally, we address the implications of our framework; suggest how facilitators, negotiation education teachers, coaches, and other professional trainers can help students learn to become reflective about conflict in order to improve their negotiation skills; and draw some conclusions about the value and limitations of the framework.

THE ROOTS OF THE FRAMEWORK IN ADULT LEARNING THEORY

Our framework was strongly shaped by adult learning theory, so we begin our chapter reviewing some key ideas from the field.

John Dewey: Learning from Experience

Many models of learning from experience have their roots in the thinking of John Dewey (1938) who examined the way in which past actions guide future actions (Boud, Cohen, and Walker, 1993; Jarvis, 1992; Kolb, 1984; Schön, 1987). Dewey observed that when people do not achieve desired results, they attend to the resulting “error” or mismatch between intended and actual outcomes. He described learning as a somewhat informal use of what is known as the scientific method: people collect and interpret data about their experiences, then develop and test their hunches even though they may not do so in a highly systematic fashion.

Dewey summed up learning from experience as involving (Dewey, 1938):

- Observation of surrounding conditions

- Knowledge of what has happened in similar situations in the past, a knowledge obtained partly by recollection and partly from the information, advice, and warning of those who have had a wider experience

- Judgment that puts together what is observed and what is recalled to see what they signify

People make meaning of situations they encounter by filtering them through information and impressions they have acquired over time. They determine whether they can rely on past interpretations and behaviors or need a new response set. They may need to search for new ideas and information or reevaluate old ideas and information. Under Dewey’s theory, learning takes place as people reinterpret their experience in light of a growing, cumulative set of insights and then revise their actions to meet their goals. In terms of learning how to handle conflict, Dewey’s theory reminds us that people can—and do—alter how they handle conflict over time, adjusting their behaviors to yield better results. However, Dewey’s approach does not help us understand why changing those behaviors is sometimes so difficult for so many people. Jack Mezirow’s theory of learning sheds light on this issue.

Jack Mezirow: Critical Reflection to Discover “Habits of Mind”

In Jack Mezirow’s theory (1991, 1995, 1997), adults shape their understanding of new situations by using “critical reflection,” a deliberate effort to examine the tacit, often unconscious belief systems held by all people. He calls these meaning perspectives (or more recently, habits of mind ) and meaning schemas (or more recently, points of view ). Mezirow defines meaning perspectives as follows:

A general frame of reference, set of schemas, worldview, or personal paradigm. A meaning perspective involves a set of psychocultural assumptions, for the most part culturally assimilated but including intentionally learned theories, that serve as one of three sets of codes significantly shaping sensation and delimiting perception and cognition: sociolinguistic (e.g., social norms, cultural and language codes, ideologies, theories), psychological (e.g., repressed parental prohibitions which continue to block ways of feeling and acting, personality traits) and epistemic (e.g., learning, cognitive and intelligence styles, sensory learning preferences, focus on wholes or parts). (Mezirow 1995, p. 42; italics added)

Another way of understanding meaning perspectives is as broad, guiding frames of mind that influence the development of an individual’s internalized meaning schemas. Meaning schemas are “the specific set of beliefs, knowledge, judgment, attitude, and feeling which shape a particular interpretation, as when we think of an Irishman, a cathedral, a grandmother, or a conservative or when we express a point of view, an ideal or a way of acting” (Mezirow, 1995, p. 43).

Meaning perspectives and schemas are the containers that shape our experiences. These containers are taken for granted and are therefore hard to see, let alone to question. Some meaning perspectives concern how we expect people to behave, in terms of categories such as race or gender, which has an impact on—and even complicate—situations in ways that can lead to conflict. This is why it may be difficult for a white person to understand how some of her views or behaviors may be perceived as racist or insensitive, for example, or for a man to understand how women could experience his actions as sexist. Through critically reflective self-exploration and questioning, a person can see the basic assumptions of his or her group and culture in a new light. In Mezirow’s theory, the process of critical reflection helps individuals understand the impact of those assumptions, which then leads them to change those assumptions and perhaps to challenge them across the broader society.

For individuals seeking to learn how to handle conflict, Mezirow’s work points to the need for critical reflection, but it does not give us much practical advice about how to probe deeply into assumptions. His theory also does not give much understanding or guidance about the deeply seated emotions.

We now turn to the work of other theorists who, like Mezirow, emphasize reflection but in doing so, bring in other dimensions of learning, for example, advice about how to probe assumptions or understand deeply seated emotions.

Action Science, Experiential Learning, and the Role of Reflection about Emotions and Affect

Chris Argyris and Donald Schön (1974, 1978) developed action science to explore the gap between what people say they want to do and what they are actually able to achieve. They argued against the behaviorists’ belief that people act somewhat blindly in response to their external environment: “Human learning . . . need not be understood in terms of the ‘reinforcement’ or ‘extinction’ of patterns of behavior but as the construction, testing, and restructuring of a certain kind of knowledge” (1978, p. 10). People often believe that they act according to one set of beliefs (espoused theory), but because of tacitly held assumptions, values, and norms, they actually act in ways that often contradict their espoused theories (theory-in-use). It is seldom possible to probe deeply into our beliefs without confronting many facets of our psychological makeup that we may find difficult to name, face, and change.

Engaging in critical reflection can evoke powerful feelings that seem at odds with instrumental, rational ways of learning from experience. Some adult educators critique this rational focus and seek to develop a broader lens with which to see the impact that critical reflection has for individual learning. Boud et al. (1993), for example, describe learning as a holistic process that involves thinking, feeling, and the will to action. They note that in English-speaking cultures, “there is a cultural bias towards the cognitive and conative aspects of learning. The development of the affect is inhibited and instrumental thinking is highly valued” (p. 12).

Boud et al. (1993) factor the affective side of learning from experience into their views. By the “affective side,” they mean all the attendant sensations and feelings that people can encounter when they have experiences. From their point of view, the affective dimension of learning includes naming and recognizing emotions and also probing the deeper, nonrational aspects of the situation in order to come to a fuller level of understanding. These authors legitimize feelings as grist for the mill of reflection. They do not shrink from feelings and even highlight that an emphasis on rationality can leave people ashamed or embarrassed about emotions.

Other experiential learning theorists, such as Heron (1992), go a step further. For these theorists, feeling precedes rational explanation and therefore can point the way to fresh insights when people revisit and reinterpret their feeling. For Heron, the affective is the psychological basis for experiential knowledge.

Sometimes experiential educators help learners get in touch with insights that they normally filter out of their awareness (Yorks and Kasl, 2006; Davis-Manigaulte, Yorks, and Kasl, 2006). In essence, feelings and the experiential knowledge that they hold are brought into awareness through the use of various forms of expression that engage the learner’s imaginative and intuitive processes, which in turn connects these processes to new conceptual possibilities. Paying attention to feelings is important for establishing an “empathic zone” (Yorks and Kasl, 2002). Creating such a zone can provide insights into the different lived experiences of others that often block pathways to understanding through rational discussion as parties talk past one another.

For individuals seeking to learn how to handle conflict, these theorists offer processes that yield productive results. For example, deliberately establishing an empathic zone after an interpersonal conflict can help set the stage for exploration of what occurred with respect (versus blame) and for building a mutually, beneficial solution through an integrative conflict resolution process.

OUR FRAMEWORK OF LEARNING THROUGH REFLECTION ON EXPERIENCE

Our framework of learning through reflection on experience highlights the role of individual reflection more than in Dewey’s model or other adult learning theory models. Our goal in the balance of this chapter is to focus readers on the challenges—and potential—of learning through reflection on experience, especially when the framework is applied to learning how to handle conflict.

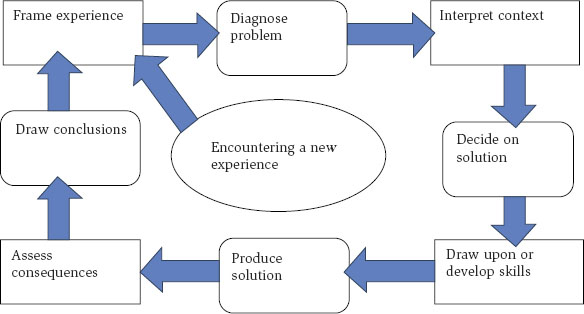

Figure 24.1 depicts a framework for learning through experience based on the model that Marsick and Watkins developed in 1990. Building on the work of John Dewey as applied to problem solving, the circle in the center represents the encountering of a new experience or problem, such as a conflict or difficult interpersonal situation. New experiences are often hard to navigate, even though people may simplify them by emphasizing what is familiar. Problem-solving steps are located at vertical and horizontal axes, and are labeled (clockwise) as North, East, South, and West. Learning steps are located in-between problem-solving steps, and are labeled (beginning clockwise just before North) as Northwest, Northeast, Southeast, and Southwest.

Figure 24.1 Marsick and Watkins’ Informal and Incidental Learning Model

Source: Adapted from Marsick and Watkins (1990).

Note: The arrows denote reflection.

In our framework of learning through reflection on experience, people use reflection to become aware of the problematic aspects of an experience, probe these features, and learn new ways to understand and address the challenges they encounter. In other words, reflection takes place at key points between these axes as the glue between the problem-solving steps and the learning. The role of reflection in this revised framework is outlined in the example below.

Problem solving begins when people encounter a new experience and frame it based on what they have learned from past experience (Northwest). Often people make these judgments quickly, without much conscious reflection. Reflection should slow the diagnosis and help a person become aware of the complexity of the situation and the assumptions used to judge the new challenge. After diagnosing a new experience, people learn more about the context of the problem (Northeast). They find out what other people are thinking and doing.

At this juncture, reflection can play a key role by opening up lines of thinking that would otherwise have remained unexplored. Using time for reflection allows for interpretation of the context as well as the emotions and leads to choices around alternative actions that are guided by recollections of past solutions and the deliberate search for other potential models for action. Before committing to any decision, the person can brainstorm options, perhaps discussing alternatives with peers and trusted others, such as coaches, educators, or facilitators.

Once a decision has been made about a course of action (East), a person develops or gathers what is needed to implement the decision (Southeast). Reflection might be anticipatory at this point and lead to a decision to gather new capabilities in order to implement the solution. Sometimes reflection occurs while the action is being implemented over time. When people are taken by some surprise in the course of action, as can happen during conflict, they may make quick judgments based on partial information. Handling a conflict without reflection is often counterproductive to reaching a sustainable solution.

Once an action is taken (South), people assess consequences and decide whether the outcomes match their goals (Southwest). Reflection after the fact allows for a full learning review: an explicit process to assess whether the outcome fulfills expectations or if there were unintended consequences, including interpersonal or emotional ones. When data are available to make sound judgments and goals are reasonably explicit, learning reviews are fairly straightforward. It is harder, however, to recognize unintended consequences, and particularly difficult after many complex conflicts. Reflection is often required at this juncture to understand the full scope of the situation. In order to fully understand the context, many sources of information should be explored and many questions asked of a wide range of people. Ignoring the full picture may yield inappropriate blame, which can be particularly damaging when there are ongoing relationships between the participants.

A full learning review leads to conclusions about results (West) and lessons learned that can be of help in planning future actions. Reflection at this point brings a person full circle to new understandings (Northwest) that are drawn in a new iteration of the cycle. Later in this chapter, we offer a further definition, as well as several examples of learning reviews in action.

Reflection stimulates learning in every phase of our framework. Although consciously using reflection to its fullest potential is difficult, individuals can learn to incorporate reflection as part of their handling of new experiences. Regular reflection sensitizes people to surprises and mismatches that signal the inadequacy of their prior stock of knowledge. Schön (1987), labeled this process of adjusting one’s behavior in the midst of a situation as reflection-in-action, highlighting how people can learn and change their behaviors while they are seeking an immediate solution. According to Schön and other action science theorists, reflection after the fact helps to draw out lessons learned that are useful for the next problem-solving cycle.

In situations of conflict, people are forced into making sense of many complex factors in a short period of time, which can influence how they interpret the context and whether they are open to identifying unintended consequences. Studies of informal learning have highlighted the fact that when contexts are highly variable and surprise rich, as is certainly the case under conditions of conflict, people’s interpretation of what is happening assumes larger significance (Cseh, 1998; Cseh et al., 1999; Volpe, Marsick, and Watkins, 1999).

Our framework calls attention to the central importance of reflection during a conflict. Specifically, we recommend that individuals use a deliberate “pause button” and focus their reflexive attention on a wide range of contextual factors that could be influencing their interpretation of what is happening, looking for unintended consequences, and thinking about alternative actions to address the situation.

The quality of reflection is central to the way in which a person makes meaning of what is occurring. Since people are often guided by internalized social rules, norms, values, and beliefs that have been acquired implicitly and explicitly through socialization, they should reflect on these and consider how these internalized constructs may be influencing their choices. In this way, our framework links to the work of Jack Mezirow (1991, 1995, 1997) and Argyris and Schön (1974, 1978). To learn deeply from experience, we agree that people must critically reflect on a full range of assumptions, values, and beliefs that shape their understandings. Our framework also links to the work of Boud et al. (1993) and Yorks and Kasl (2002) by focusing on the role of emotions and feelings. At the heart of the framework of learning through reflection on experience is a dynamic and ongoing interaction of action—having an experience—and reflection that helps a person to interpret and reinterpret experience.

Two case illustrations of learning through reflection on experience follow.

Case Example: Reflection after Conflict

In her early career as a lawyer, Janice described her style of negotiating with people as “obnoxious” and “overbearing” (Weaver, 2011). Over time, she ran into problems due to her outspokenness and take-no-prisoners behaviors. Janice lived through a mounting number of conflicts during which her tone and behaviors were criticized. After a judge sanctioned her for her behavior in the courtroom and her law firm faced a fine, she stepped back and thought about whether her approach was getting her where she wanted to go.

She engaged in some honest self-appraisal and realized that her approach was causing problems. After a period of personal reflection, she decided to gather information through negotiation classes exploring alternative styles. As her awareness of competitive versus collaborative styles increased, she decided to experiment with different approaches to resolving conflicts outside the classroom setting. Her ongoing experiences with new styles and reflection on the positive outcomes allowed her to begin to internalize a different modality, a different way of being (Weaver, 2011). After her internal learning review, Janice concluded that she should use her toughest style of negotiating only under certain, very limited, circumstances.

In her description of her personal learning process, Janice described how her ongoing desire to get better at negotiation allowed her to understand that every conflict is unique and that her style of negotiating needed to be nuanced, tailored to the specifics of the individuals and circumstances involved, and actively chosen rather than one-style-fits-all. Her ongoing reflection and learning show that she has moved from West to Northwest, where she is ready to face new experiences. Janice found that over time, her new and more flexible approach to negotiation brought solid outcomes and also stronger relationships with her counterparts, colleagues, and peers.

Seen through our framework of learning through reflection on experience, Janice’s process of learning how to handle conflict clearly required reflection at several points: when she acknowledged that her outspoken approach was no longer working, when she decided how to gather information about other options, and when she reflected on the successful outcome of using a more nuanced approach to conflict resolution.

Case Example: Reflection with the Help of a Trusted Other

Kelly is an educator who describes herself as someone who was raised with explicit expectations about remaining “quiet” and always behaving as “a good girl” (Weaver, 2011). In her early career, she struggled with the idea that it was acceptable, or even safe, to speak up and negotiate, especially with authority figures.

Kelly had difficulty handling conflict with her bosses for the first decade of her career and eventually worked with a psychotherapist on this issue. Kelly’s meaning perspective about authority and how to interact with authority was initially an unconscious constraint. By using critical reflection in conjunction with a trusted other person, she eventually recognized her meaning perspective’s power over her emotions and behavior. The empathic zone that was created in that relationship helped her to talk about and understand the emotional aspects of her fears. As her understanding grew, she became increasingly willing to speak up for herself, eventually becoming confident handling conflicts with her boss and other authority figures.

Kelly learned that it was within her control to improve how she handles problematic situations by using reflection before, during, and after conflicts. She said, “As I get older and reflect upon things . . . I say: ‘Well, I could’ve said this. I could’ve done this differently’ you know? It’s like having a reflective mind, so you’re always looking at the situation again, and thinking: ‘How could I have done that differently and change the outcome?’”

In addition, Kelly now sets aside time to assess difficult situations and make deliberate choices about her actions. By planning what she will say to her boss and role-playing negotiations with trusted friends and family members, Kelly has learned to speak up on her own behalf, overcoming longstanding behavioral habits. Even in the midst of a conflict with her boss, she described an ability to pause and reflect, carefully choosing her words and actions in order to move the discussion to resolution.

Looking at Kelly’s situation solely through the work of Mezirow would yield a somewhat one-dimensional and decontextualized analysis. While such an analysis would refer to her changed meaning perspective, it could not reveal how Kelly was regularly overwhelmed by conflict situations, the strong pain and emotions that were involved, or how hard it was for her to learn to handle conflict in new ways, including the many setbacks that she had over more than a decade. It also would not reveal the important role that a facilitator—in her case, the psychotherapist—played in her learning.

Our framework of learning through reflection on experience integrates the impact of reflection and critical reflection in situations like Kelly’s and the key role that a trusted other person can play in learning. Although Kelly had reflected on her issues with authority in her early career, it was not until she engaged in a deeper process of critical reflection that she was able to break through some of her longstanding habits. Powerful emotions often arise as people try to learn from their experiences. These feelings need to be acknowledged and sometimes probed with professionals—whether coaches, trainers, or (for some individuals) psychologists or psychotherapists. Learning through reflection on experience can be strengthened by working with trusted other people, who can serve as catalysts to the learning process.

We now turn to a more in-depth discussion of different kinds of reflection and the kinds of questions that can be employed to encourage reflection, especially before, during, and after conflict situations.

Reflection and Critical Reflection

Simple reflection involves a review of attendant thoughts, feelings, and actions without questioning one’s interpretation or meaning of an experience such as a conflict. But people can be misled by their interpretation of experience. They might frame the experience or solutions inaccurately, especially if they miss information or signals about the nature of the new challenge. Prior assumptions and beliefs can lead to a partial, limited, or incorrect assessment of a situation. Simple reflection in our framework is stimulated by questions such as the following:

- What did I intend?

- What actions, feeling, emotion, or results surprised me?

- How is this experience alike or different from my prior experiences?

- What metaphors and stories capture my experience and differentiate it from those of others?

- What does this experience tell me about worldviews other than my own?

Critical reflection and critically reflective questions do more than simple reflection. Critical reflections probe the context, the assumptions of the people involved, and the way these influence their judgments, expectations, and behaviors. Such questions look more like the following:

- What else is going on in the environment that I might not have considered but that may have an impact on the way I understand the situation?

- What is the other person’s point of view, assumptions, and expectations, and how can I find out more about them to be sure?

- In what ways could I be wrong about my hunches?

- How are my own intentions, strategies, and actions contributing to outcomes I want to avoid?

- In what way might I be using inapplicable lessons from my past to frame problems or solutions, and is this framing accurate?

- Are there other ways to interpret the feelings I have in this situation? How can I better gain a pathway into experience of other people that might challenge or change my assumptions?

It is not easy to engage in critical reflection during a conflict or in the midst of a longstanding interpersonal problem, although it can be done with practice. Critical reflection demands an open mind and heart, including the willingness to slow things down (to push the reflexive “pause button”), to question one’s interpretations of the situation and the other person (or people) involved, to listen carefully with a suspension of blame, as well as to probe for alternative viewpoints. Critical reflection is more easily carried out before or after the fact, when emotions and feeling can be examined and understood, and with time to learn new skills in order to change one’s customary response patterns.

WHY COACHES AND FACILITATORS CAN BE CATALYSTS FOR LEARNING THROUGH REFLECTION

Just as coaches can help individuals, facilitators can help groups of people reflect on both the cognitive and noncognitive dimensions of conflict. Individuals can be in a rut (Dewey, 1938) about how they think about conflicts and how they approach negotiations, where they do not know how to interrupt old habits. As we saw in the example of Kelly, trusted other individuals can help, especially those trained to encourage reflection, such as psychiatrists, coaches, adult learning specialists, negotiation educators, and facilitators.

Facilitators focus on helping individuals to critically reflect on their patterns—for example, their patterns of handling conflict, including those who often avoid speaking up and negotiating. They can help individuals reflect on what has gone well during a specific conflict and what was not satisfactory. Over time, facilitators can help clients build skills to better address conflict by encouraging them to always use reflection to learn from experience, breaking down assumptions, learning to probe the other person’s point of view, and debriefing what was intended compared to what happened. The challenge may be greatest when conflict emerges unexpectedly.

Facilitators can also help people attend to the noncognitive dimensions of conflict. Perhaps the most powerful first step for doing so is to make space for naming and working with feelings and emotions. There is often a shame and stigma associated with discussing feelings and showing emotion, especially in groups. Facilitators can help to create a respectful, safe environment for feelings to be expressed, such as the empathic zone referred to above. Such an environment can be constructed through encouraging what Torbert (2001) describes as first-person inquiry and practice. First-person inquiry involves paying attention to one’s own intentions and reactions and developing a capacity for attention and self-awareness. Bringing this first-person mindfulness to second-person inquiry through mindful use of how we interweave our framing, advocating, illustrating, and inquiring in our dialogues and awareness of how a situation is playing out is foundational for creating empathic zones. Facilitators in groups may well have to stand tough when others wish to avoid feelings and emotions or, even worse, “punish” a person for showing and discussing them. To do so, facilitators need to be willing to take the time to identify and address underlying values and beliefs that are influencing cultural norms and specific behaviors in the room.

One step that facilitators use to encourage learning in groups is the process known as learning review. Learning reviews help people to become more aware of goals, outcomes, and contextual factors that influence the way they understand a situation, assumptions that influence actions, and feelings that they cannot articulate but recognize are operative. They facilitate reflection on experience, which sometimes surfaces conflicts in points of view but also creates a process for learning from experiences about differences and reconciling conflicts based on deep probing of assumptions and beliefs. A learning review is typically guided by four questions:

- What did we intend to happen?

- What happened?

- Why did it happen that way?

- How can we improve what happened?

Facilitators can identify different ways for groups to do such learning reviews, helping the individual members gain skills in carrying them out, and encouraging them to articulate their viewpoints and discuss them openly with others. They can create a culture where conflict is expected and recognized for the value it will bring to results and where learning reviews become routine.

Two case examples of facilitated learning through reflection follow.

Case Example: After-Action Reviews

The U.S. Army developed the after-action review (AAR) for the purpose of incorporating reflection into their learning (Sullivan and Harper, 1996). AARs are structured in the learning reviews in the learning-through-experience framework we have described. They are typically held in the middle of a battle, but they are also being used in noncombat situations. It is a deliberate process to encourage individuals to be reflective and examine the unexpected and unintended without blame and with a forward-looking orientation to handle similar situations better when they arise again.

AARs focus attention on goals, which in itself can increase conscious learning. Data are collected to track actions and results so that the discussion can be based on what is called “ground truth,” that is, accurate data-based reports of what took place on the battle ground. Ground truth in the Army is collected by using computer-based technology that can provide detailed information on moves that were made. Although data are collected and reviewed, about 75 percent of the time spent in an AAR is focused reflection on why things occurred and how people can improve moving forward. Ground rules are set for dialogue and reflection that include freedom to speak up, regardless of one’s rank, a norm of honesty rather than sugarcoating or holding back for fear of reprisal, and strict avoidance of blame.

AARs are being adapted by corporations for use in noncombat situations where the enemy may not be as easily identified, the motivation for working together not as clear, and the consequences of a mistake not as obvious. Conflicts in civilian life may also not be resolved by a clear-cut win-loss outcome. As the examples throughout this chapter illustrate, conflicts are handled best with attention to the complexities of the situation, and with reflection by all of the participants.

Case Example: Using an Action Science Facilitator to Learn to Handle Conflict

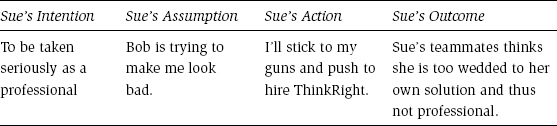

Let us imagine that a businesswoman named Sue had the conversation with her team members that we present in exhibit 24.1 . In this conversation, Bob (one of Sue’s peers at work) challenged Sue over a recommendation she made. Because she was upset at the brewing conflict with Bob, Sue decided to meet with an action science coach who uses our learning through reflection on experience framework.

The action science coach helps Sue to identify her explicit and implicit intentions for this interaction. At first, Sue identifies her goal as trying to get the best solution to the problem, but eventually she acknowledges her conflicting goals and emotions, such as her strong desire to win in her confrontation with Bob. She might also realize that she values looking good in front of her teammates, especially in light of her perceptions of the subtle, and not-so-subtle, gender discrimination at the company. Most of all, she wants to be respected as a professional and therefore has to decide what that means in this situation. The coach then helps Sue recognize the mismatch between her intentions (her espoused theory) and outcomes (her theory-in-use), a mismatch that stimulates Sue’s desire to learn a new way of negotiating this kind of difficult situation going forward.

Exhibit 24.1 Sue’s Dialogue with Her Teammates

| What Sue Felt or Thought But Did Not Say | What Sue and Teammates Said |

| These guys! We’ve been chewing on this question ever since we began meeting. Someone must know something about this situation that I don’t know. | Sue: So, that summarizes what we have agreed to. I think we disagree about whether we think that the people we want to reach actually shop in the kind of convenience store we have targeted. I suggest that we hire ThinkRight consultants to do focus groups to check out our assumptions on this one. |

| What’s Bob up to now! This is coming from left field. | Bob: You have been pushing those people from the moment we met. What’s in it for you to use these guys? |

| Here we go again. These guys are trying to make me look like I don’t know what I am doing. | Sue: Huh? I am just trying to move us forward. We have been circling around this question ever since we began meeting. I want us to move forward. |

| What do I do with this one . . . he’s made it look like, if I confront him, he’s right. The jerk! He’s not really joking. | Bob: Yeah, yeah. I know how you women work. Give you an inch and you take a mile [as if in humor; laughter all around from others]. You are just trying to railroad your decision through. [Others nod in agreement; no one else speaks up.] |

As they review the conflict, the coach probes Sue’s assumptions about her teammates and her interactions with them, and asks about Bob’s likely reasoning as well. This process will make it clear to Sue that she and Bob have very different framings and interpretations of the situation. Since they are both influenced by deeply held beliefs and values, these strong feelings are affecting their behavior toward each other. These feelings may lead them to actions that actually create the consequences that they say they do not wish to experience.

When the coach helps Sue to map the links between her assumptions, her emotions, and the ways both shape her actions, Sue can see how the chain of consequences is directly connected to her initial assumptions and emotions. Exhibit 24.2 illustrates this kind of mapping. It takes some time to map this kind of causal linkage with any degree of accuracy, as the coach has to test various interpretations. People’s responses often reflect views in the dominant culture, but the goal must be to map Sue’s own sense of the causal linkages. Ultimately the coach helps Sue to see that her interpretations are likely to lead her to the very gap she says she wants to avoid between her various stated intentions and the likely outcomes from the interaction: she wants to be seen as a professional, but her actions are not appropriate for the situation at hand, and may well be seen by her colleagues as unprofessional.

Underlying beliefs and values and habits of behavior—Sue’s, Bob’s, the other teammates’, and the company’s—are not easily changed even when they might be recognized as unproductive. Using the learning-through-reflection-on-experience framework, the coach supports Sue’s personal reflection as well as her critical reflection on the situation at work, including Sue’s perceptions of discrimination. Over a series of sessions, the coach can work with Sue to develop her ability to reflect on her day-to-day experiences, strengthening her understanding and skill at handling conflict.

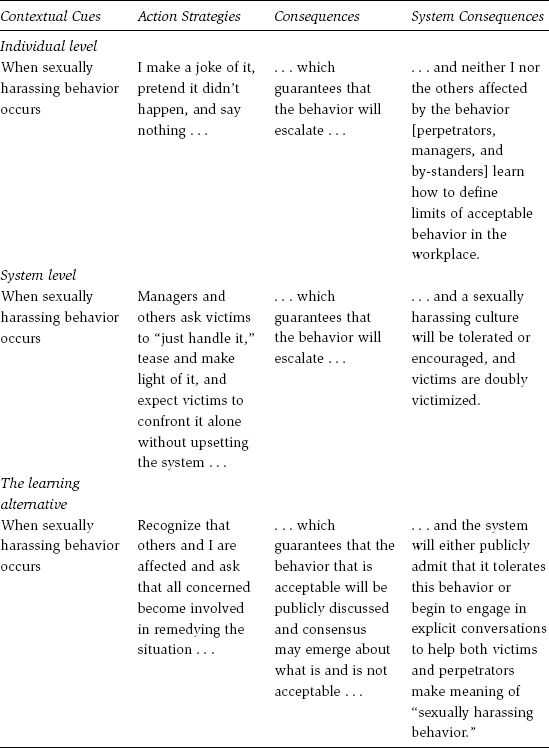

By mapping out responses in a variety of situations, reflecting and discussing those reflections with others, people can identify deeper patterns that cause conflict. When this kind of process happens across many organizations, it may begin to produce a change in the cultural patterns themselves. For example, when Karen Watkins at the University of Georgia taught a graduate course in action science (Marsick and Watkins, 1999), two individuals from different organizations had brought in cases in which sexual harassment was an underlying theme. In the group discussion that ensued, many individuals agreed that this was a significant societal concern. The class mapped these themes using common responses, and the way in which these responses would have to change in order to allow greater learning to occur. These maps are shown in table 24.1 . Action science can help to make public issues that otherwise could not easily be addressed because of potential repercussions.

Exhibit 24.2 Mapping One Possible Set of Causal Links in Sue’s Case

Table 24.1 Action Science Map around Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

Source: Marsick and Watkins (1999).

ENCOURAGING DIALOGUE AND NEW IDEAS IN OUR LEARNING THROUGH REFLECTION ON EXPERIENCE FRAMEWORK

As the examples show, people are often blind to their own views. Mezirow (1991, 1997) recommends dialogue and what he calls “rational discourse” as a way of identifying and considering preferred ways of acting. The conditions for discourse seem impossibly idealistic at first glance:

Those participating have full information; are free from coercion; have equal opportunity to assume the various roles of discourse (to advance beliefs, challenge, defend, explain, assess evidence, and judge arguments); become critically reflective of assumptions; are empathic and open to other perspectives; are willing to listen and to search for common ground or a synthesis of different points of view; and can make a tentative best judgment to guide action. (Mezirow 1997, p. 10)

Despite these seemingly impossible standards, we have created action science dialogue groups based on our framework, and results show that they in fact stimulate a broader exploration of relevant issues and ideas.

In our work, we have found that it is easier to help a person to identify, name, and deal with powerful feelings after a real or perceived conflict or threat occurs. All facilitators should seek to create empathic zones in which participants can probe, acknowledge, and address fears; separate real from imagined consequences; and facilitate brainstorming about working with the specific conflict.

Facilitators of groups can also engage people in anticipatory reflection of alternative worldviews in order to step outside current mental models that may be restricting new insights and skill development. Some theorists find that expressive ways of tapping into tacit experiential knowing can aid individuals in breaking through their habits and be open to new insights (Yorks and Kasl, 2006; Davis-Manigaulte et al., 2006). For example, Richard Leachman (1999) uses abstract paintings along with word descriptions to help people create, populate, visit, and experience new worlds. He then invites people to revisit a problem through the lens of experience created by their foray into this alternative space. Other experiential educators engage people in dance, poetry, metaphor, guided imagery, or painting. Bruce Copley (1999) designs learning experiences that use all of the senses. Activities such as these help set the stage for creating an empathic zone where new insights can be found.

CONCLUSION

We have introduced, described, and illustrated a framework for learning through reflection on experience that we believe holds potential for those who help others to address and learn from conflict. The value of reflection is that it is available to everyone. At the same time, as Ellen Langer (1989) has observed regarding a similar capacity for mindfulness, the very availability of mindfulness may make people discount its usefulness or take it for granted.

In order to use reflection to learn from experience, people have to slow down their thinking process so that they can critically assess it. They need to get in touch with deeper feelings, thoughts, and factors that lie outside their current mental and sensory models for taking in and interpreting the world that they encounter. Although some individuals may find this process disconcerting and at times difficult, we believe that individuals need to step outside the frameworks and cultural norms by which they understand experience. At these moments, reflection can lead to new insight, but it is often a process that needs support from facilitators and trusted other people who can encourage the reflective process. As people develop new capabilities and habits, ongoing reflection on their experiences will help them learn additional skills and more nuanced approaches to complex situations.

When applied to conflict and learning to handle conflict, our framework of learning through reflection on experience can support individuals as they seek to change their patterns and styles of negotiating, building alternative patterns over time that will help them to resolve the conflicts in their lives more successfully.

References

Argyris, Chris, and Donald A. Schön. Theory in Practice: Increasing Organizational Effectiveness . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1974.

Argyris, Chris, and Donald A. Schön. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1978.

Boud, David, Ruth Cohen, and David Walker, eds. Using Experience for Learning . Buckingham, UK, and Briston, PA: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press, 1993.

Copley, Bruce. “Cogmotics: Breathing Life into Education and Learning through the Fine Art of Holistic Animation.” Presentation at the Annual Conference of the Management Institute, Lund, Sweden, May 1999.

Cseh, Maria. “Managerial Learning in the Transition to a Free Market Economy in Romanian Private Companies.” PhD dissertation, University of Georgia, 1998.

Cseh, Maria, Karen E. Watkins, and Victoria Marsick. “Reconceptualizing Marsick and Watkins’ Model of Informal and Incidental Learning in the Workplace.” In K. Peter Kuchinke, ed., Proceedings of the Academy of Human Resource Development Conference . Baton Rouge, LA: Academy of Human Resource Development, 1999.

Davis-Manigaulte, Jacqueline, Lyle Yorks, and Elizabeth Kasl. “Expressive Ways of Knowing and Transformative Learning.” In Edward W. Taylor, ed., Teaching for Change: Transformative Learning in the Classroom . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006.

Dewey, John. Experience and Education . New York: Collier Books, 1938.

Heron, John. Feeling and Personhood: Psychology in Another Key . London: Sage, 1992.

Jarvis, Peter. Paradoxes of Learning: On Becoming an Individual in Society . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992.

Kolb, David. Experiential Learning . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1984.

Langer, Ellen J. Mindfulness . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1989.

Leachman, Robert. “Experiential Simulations of World Views and Basic Assumptions.” Presentation at the Annual Conference of the Management Institute, Lund, Sweden, May 1999.

Marsick, Victoria J., and Karen Watkins. Informal and Incidental Learning in the Workplace . London: Routledge, 1990.

Marsick, Victoria J., and Karen Watkins. Facilitating the Learning Organization: Making Learning Count . London: Gower, 1999.

Mezirow, Jack. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1991.

Mezirow, Jack. “Transformation Theory of Adult Learning.” In Michael R. Welton, ed., In Defense of the Lifeworld: Critical Perspectives on Adult Learning . Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

Mezirow, Jack. “Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice.” In Patricia Cranton, ed., Transformative Learning in Action: Insights from Practice . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997.

Schön, Donald. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987.

Stone, Douglas, and Bruce Patton. Difficult Conversations . New York: Penguin Books, 2000.

Sullivan, Gordon R., and Harper, Michael V. Hope Is Not a Method: What Business Leaders Can Learn from America’s Army . New York: Broadway Books, 1996.

Thompson, Leigh. The Mind and Heart of the Negotiator . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice-Hall, 2005.

Torbert, William R. “The Practice of Action Inquiry.” In Peter Reason and Hilary Bradbury, eds., Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001.

Volpe, Marie, Victoria J. Marsick, and Karen E. Watkins. “Theory and Practice of Informal Learning in the Knowledge Era.” In Victoria Marsick and Marie Volpe, eds., Informal Learning in the Workplace . San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler, 1999.

Watkins, Karen, and Marsick, Victoria J. Sculpting the Learning Organization . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993.

Weaver, Dorothy E. “How Professional Women Learn to Speak Up and Negotiate for Themselves in the Workplace.” EdD dissertation, Teachers College, Columbia University, 2011. http://gradworks.umi.com/34/84/3484283.html

Yorks, Lyle, and Elizabeth Kasl. “Toward a Theory and Practice for Whole-Person Learning: Reconceptualizing Experience and the Role of Affect.” Adult Education Quarterly 52 (2002):176–192.

Yorks, L., and Kasl, E. “I Know More Than I Can Say: A Taxonomy for Using Expressive Ways of Knowing to Foster Transformative Learning.” Journal of Transformative Education , 2006, 4 (1):1-22.

Zuckerman, A., and Chaiken, S. “Mood Influences Persuasion in an Interpersonal Setting.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Society, Washington, DC, May 1997.