CHAPTER THIRTY

INTRACTABLE CONFLICT

Peter T. Coleman

When destructive conflicts persist for long periods of time and resist every attempt to resolve them constructively, they can appear to take on a life of their own. We label these intractable conflicts . They can occur between individuals (as in prolonged marital disputes) and within or between groups (as evidenced in the antiabortion/pro-choice conflict) or nations. Over time, they tend to attract the involvement of many parties, become increasingly complicated, and give rise to a threat to basic human needs or values. Typically they result in negative outcomes for the parties involved, ranging from mutual alienation and contempt to atrocities such as murder, rape, and genocide.

Today, of the roughly seventy geopolitical conflicts that the International Crisis Group is monitoring, fifteen have lasted between one and ten years, twelve have persisted between eleven and twenty years, and forty-three have dragged on for more than twenty years. This last category of long-enduring conflicts is what I refer to as the 5 percent of intractable conflicts (Coleman, 2011).

In a series of studies analyzing the Correlates of War database, a source of information on all interstate interactions around the world from 1816 to 2001, Paul Diehl and Gary Goertz (Diehl and Goertz, 2000; Klein, Goertz, and Diehl, 2006) have been exploring the dynamics of ongoing competitive relationships between states that employ either the threat or the use of military force. Of the 875 rivalries they have identified over the time span of the database, they estimate that between 5 and 8 percent become enduring, persisting more than twenty-five years with an average duration of thirty-seven years. From 1816 to 2001, approximately 115 enduring rivalries have inflicted havoc in the geopolitical sphere.

Although the percentage of enduring rivalries in terms of all rivalries is small (5 percent), these ongoing disputes are disproportionately harmful, destructive, and expensive. Together they have accounted for 49 percent of all international wars since 1816, including World Wars I and II, and have been associated with 76 percent of all civil wars waged from 1946 to 2004 (DeRouen and Bercovitz, 2008). These protracted conflicts include those today in Israel-Palestine, Kashmir, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Colombia, and Cyprus. They cause extraordinary levels of misery, destabilize countries and entire regions, inflict terrible human suffering, and deplete the international community of critical resources such as humanitarian aid and disaster funding.

This chapter provides a practical overview of our current understanding of intractable conflict. It has six sections. It begins with a basic definition of intractable conflicts that distinguishes them from more manageable forms of conflict. It then outlines five common paradigms for addressing these types of conflicts. The third section outlines a variety of component parts of intractable conflict that scholars have identified as sources of their intransigence. Next, a dynamical-systems model of intractable conflict is presented, which helps to integrate our understanding of how the many subcomponents combine to foster intractability. The next section offers general guidelines for intervention, and the chapter concludes with a discussion of implications for training intervenors and disputants.

DEFINING INTRACTABLE CONFLICT

Intractable conflicts are essentially conflicts that persist because they appear impossible to resolve. Scholars have used labels such as deeply rooted conflict (Burton 1987), protracted social conflict (Azar, 1986), moral conflict (Pearce and Littlejohn 1997), and enduring rivalries (Goertz and Diehl, 1993) to depict similar phenomena. Kriesberg (2005) stresses three dimensions that differentiate intractable from tractable conflicts: their persistence, destructiveness, and resistance to resolution.

Most intractable conflicts do not begin as such but become so as escalation, hostile interactions, sentiment, and time change the quality of the conflict. They can be triggered and emerge from a wide variety of factors and events but often involve important issues such as moral and identity differences, high-stakes resources, or struggles for power and self-determination (Burgess and Burgess, 1996). Intractable conflicts are typically associated with cycles of high and low intensity and destructiveness, are often costly in human and economic terms, and can become pervasive, affecting even mundane aspects of disputants’ lives (Kriesberg, 1999; Coleman, 2003).

APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING INTRACTABLE CONFLICT: FIVE PARADIGMS

Over the past several decades, the literature on social conflict has put forth a large array of approaches for prevention, intervention, and reconstruction work with protracted social conflicts. This section outlines five major paradigms employed currently in framing research and practice in this area: realism, human relations, pathology, postmodernism, and systems (see Coleman, 2004). These paradigms are, in effect, clusters of approaches that vary internally across a myriad of important dimensions and overlap to some degree with approaches from other paradigms. The five paradigms are presented in order from most to least influential in the field today.

The Realist Paradigm

Historically this perspective has been the dominant paradigm for the study of war and peace in history, politics, and international affairs. Essentially a political metaphor, it views protracted conflicts as dangerous, high-stakes games that are won through strategies of domination, control, and countercontrol (see Schelling, 1960). Although they vary, approaches of this nature tend to assume that resources and power are always scarce, that human beings are basically flawed (always capable of producing evil) and have a will to dominate, and that one’s opponents in conflict at any point may become aggressive. Consequently, they present an inherently conflictual world with uncertainties regarding the present and future intentions of one’s adversary, leading to risk-aversive decision making. Thus, intractable conflicts are thought to result from rational, strategic choices made under the conditions of the “real politics” of hatred, manipulation, dominance, and violence in the world. These conflicts are seen as “real conflicts” of interest and power that exist objectively due to scarcities in the world and are exacerbated by such psychological phenomena as fear, mistrust, and misperception. In this context, power is seen as both paramount and corrupting, and real change is believed to be brought about primarily through power-coercive command-and-control strategies.

The realist approach highlights the need for strong actions to provide the protections necessary and requires that we find effective methods for minimizing acts of aggression and bolstering a sense of social and institutional stability, while at the same time confronting the underlying patterns of intergroup dominance and oppression that are the bedrock of many conflicts. Examples of this approach include the use of direct force, Machiavellian approaches to statesmanship, game-theoretical strategies of collective security and deterrence, and “jujitsu” (redirecting the force of an opponent against itself) tactics of community organizing (Alinsky, 1971). They also include acts of stabilization to offset uncertainties, such as establishing clear and fair rules of law, a trustworthy government and judiciary, fair and safe voting practices, and a free press. In some settings, they involve activism to offset power imbalances, including raising awareness of specific types of injustice within both high-power and low-power communities; helping to organize, support, and empower marginalized groups; and bringing outside pressure to bear on the dominant groups for progressive reforms (Deutsch, 1985).

The emphasis given by the realist paradigm to the dangerous power politics and anarchy operating within the context of protracted conflicts is crucial. It highlights basic human concerns over threats to security, stability, and justice that lie at the heart of most experiences of protracted conflict. In turn, its myriad theories and approaches offer many insights and techniques for working politically in such systems. However, this orientation is not without its drawbacks. Its assumptions of rational choice are “economic” in nature (reasoning through efficient cost-benefit analyses), which, although valid under certain conditions, fails to account for other types of human reasoning and action (such as social, legal, moral, and political forms of reasoning) that function differently and have a large impact on decisions and outcomes in conflict settings (see Diesing, 1962, for an extensive discussion). In addition, its “preventative orientation” to managing conflict (see Higgins, 1997) leads to a focus on short-term security needs, worst-case scenarios, and an overreliance on strategies of threat and coercion (see Levy, 1996). Furthermore, its core competitive assumptions regarding the nature of power and security, the availability of resources, and the inevitability of the other’s aggression can limit a party’s response options and typically results in competitive and escalatory dynamics and self-fulfilling prophesies that foster further entrenchment in the conflict (see Deutsch, 1973, 2000).

The Human Relations Paradigm

An alternative to the realist paradigm emerged primarily through the social-psychological study of conflict and stresses the vital role that human social interactions play in triggering, perpetuating, and resolving conflict. Based on a social metaphor, its most basic image of intractable conflict is of destructive relationships in which parties are locked in an increasingly hostile and vicious escalatory spiral and from which there appears to be no escape. With some variation, these approaches view human nature as mixed, with people having essentially equal capacities for good and evil, and they stress the importance of different external conditions for eliciting either altruism and cooperation or aggression and violence. This orientation also identifies fear, distrust, misunderstanding, and hostile interactions between disputants and between their respective communities as primary obstacles to constructive engagement. Thus, subjective psychological processes are seen as central as well, significantly influencing disputants’ perceptions, expectations, and behavioral responses and therefore largely determining the course of conflict (see Deutsch, 1973). From this perspective, change is thought to be brought about most effectively through the planful targeting of people, communities, and social conditions and is best mobilized through normative—reeducative processes of influence (Fisher, 1994).

The human relations approach promotes a sense of hope and possibility under difficult circumstances. It stresses that we recognize the central importance of human contact and interaction between members of the various communities for both maintaining and transforming protracted conflicts. Human relations procedures include various methods of integrative negotiation, mediation, constructive controversy, and models of alternative dispute resolution systems design. In addition, scholars have found that establishing integrated social structures, including ethnically integrated business associations, trade unions, professional groups, political parties, and sports clubs, is one of the most effective ways of making intergroup conflict manageable (Varshney, 2002). Other variations include interactive problem-solving workshops (Kelman, 1999), town meeting methodologies, focused social imaging (Boulding, 1986), and antibias education.

The focus of the human relations paradigm on the promotion of positive moments of human contact between deadly enemies brings, if nothing else, hope to situations deemed by many to be hopeless. Even its less optimistic forms offer visions of the future of the conflict that are less violent, less traumatic, and well worth working for. Such seeds of hope can be priceless to a community locked in despair. In addition, the many procedures developed through the years for inducing cooperation, analyzing human needs, and fostering tolerance or reconciliation are creative and impressive and offer genuinely practical tools for the repair of even severely damaged relations.

Nevertheless, relationally focused strategies of intervention, when not complemented by other methods, often fall well short of their objectives in hazardous situations of protracted conflict. Although overstated, they have been criticized by some realists as “at best well-intentioned, at worst soft and driven by sentimentalism, and for the most part irrelevant” (Lederach, 1997). They typically work best in situations where there is an a priori acceptance of the values of reciprocity, human equality, shared community, fallibility, and nonviolence (Deutsch, 2000). Contexts that are void of these norms, and the laws and institutions that regulate them present substantial challenges to the constructive use of relational strategies. For example, in societies where male superiority goes unquestioned, the use of cooperative strategies to address protracted gender conflicts may in fact perpetuate the oppressive quality of gender relations in that context. Finally, most human relations approaches are based on the values and assumptions of scientific humanism and planned social change (Fisher, 1994). These values and assumptions define the boundaries of these approaches and limit their applicability in situations where such values are not shared.

The Pathology Paradigm

This view pictures intractable social conflicts as pathological diseases—as infections or cancers of the body politic that can spread and afflict the system and therefore need to be correctly diagnosed, treated, and contained. A medical metaphor, it views its patient, the conflict system, as a complicated system made up of various interrelated parts that exist as an objective reality and can be analyzed and understood directly and treated accordingly. These patients are thought to be treated most effectively by outside experts who have the knowledge, training, and distance from the patient necessary to accurately diagnose and address the problem. This perspective views humans and social systems as basically health-oriented entities that, due to certain predispositions, neglect, or exposure to toxins in the environment, can develop pathological illnesses or destructive tendencies. Treatment of these pathologies, particularly when they are severe, is seen as both an art and a science, with many courses of treatment that can bring their own negative consequences to the system. Although not as common as the realist and human relations paradigms, the medical model is particularly popular with agencies, community-based organizations, and nongovernmental organizations working in settings of protracted conflict.

A classic example of the medical approach is Volkan’s tree model (Volkan, 1998), which recommends working collectively with communities in conflict to unearth the “hidden transcripts” (hidden resistances), the “hot” locations (symbolic sites), and the chosen traumas and glories that maintain oppositional group identities. This diagnostic phase is followed by a series of psychopolitical dialogues between influential representatives of relevant groups, who then work toward a “vaccination” campaign to reduce poisonous emotions at the local community, governmental, and societal levels. Other activities aimed at containing the spread of pathologies of violence in communities include strategies of nonviolence and many types of preventative diplomacy (such as early warning systems), crisis diplomacy, peace enforcement (conflict mitigation), and peacekeeping. In addition, this approach is associated with a wide variety of activities for postconflict reconstruction, including rebuilding damaged infrastructure, currency stabilization, demining, creating legitimate and integrated governments, demilitarizing and demobilizing soldiers, resettling displaced peoples, and establishing awareness of and support for basic human rights (Wessells and Monteiro, 2001).

Understanding and treating the pathological aspects of protracted conflicts has unquestionable value. The needs to contain high levels of tension and violence, unearth and assuage destructive, unconscious motives and hidden tensions and agendas, and address toxic emotions, trauma, and societal-level damage are straightforward indeed. However, once again, this worldview is limited in its capacity to manage protracted conflict unaided. For example, the amelioration of tension and violence in protracted conflicts is often only temporary and superficial. As Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “Peace is not merely the absence of tension, but the presence of justice.” Although hostilities between people may be temporarily controlled by the acceptance of a cease-fire or peacekeeping troops, the conflict may move no closer to resolution and may in fact become more intractable as a result of the disengagement of the parties (Fisher, 1997). In addition, the approach of identifying and exposing covert motives and interests rests on the straightforward assumption that doing so is good—that it is both possible and constructive to unearth such motives, that people have the capacity and support to tolerate such information when it is forthcoming (about themselves, their government, their businesses, and so on), and that people, corporations, and governments will then have the motivation and the capacity to reform. These assumptions, although hopeful, are often inaccurate. Finally, this orientation is based on a deficit model, with a focus on that which is wrong or pathological in a conflict system. While important, this orientation often neglects focusing on positive responses such as resiliency or altruistic and ethical behavior under difficult circumstances, and it can foster a negativity bias in our understanding of and responses to the phenomena.

The Postmodern Paradigm

This perspective portrays intractable conflicts as rooted in the ways we make sense of the world. A communications metaphor, its most basic image is of conflict as a story—a narrative or myth that provides a context for interpretation of actions and events, both past and present, that largely shapes our experience of ongoing conflicts. Thus, conflict comes from the way parties subjectively define a situation and interact with one another to construct a sense of meaning, responsibility, and value in that setting. Intractable conflicts, then, are less the result of scarce resources, incendiary actions of parties, or struggles for limited positions of power than they are a sense of reality, created and maintained through a long-term process of meaning making through social interaction (Lederach, 1997; Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997). This worldview highlights a form of power as meaning control: an insidious primary form of power that is often quietly embedded in the assumptions and beliefs that disputing parties take for granted. It suggests that it is primarily through assumptions about what is unquestionably “right” in a given context that different groups develop and maintain incommensurate worldviews and conflicts persist. Thus, change is believed to be brought about by dragging these assumptions into the light of day through critical reflection, dialogue, and direct confrontation, thus increasing disputant awareness of the complexity of reality, our almost arbitrary understanding of it, and the need for change.

The postmodern approach can be operationalized through a variety of channels, including targeting how conflicts are depicted in children’s history texts, challenging the media’s role in shaping and perpetuating conflict, and working at the intragroup level on renegotiating oppositional identities (Kelman, 1999). Many nongovernmental organizations facilitate small dialogue groups of disputants who come together with the support of carefully structured facilitation to share their memories and experiences of conflicts in the presence of others who hold profoundly different views. These dialogues offer an experience that is distinct from problem solving, mediation, or negotiation in that they discourage persuasion and argumentation and encourage alternative forms of intergroup contact that emphasize learning, openness to sharing, and gathering new information about oneself, the issues, and the other. Other examples of this approach include the reframing of environmental conflicts (see Lewicki, Gray, and Elliott, 2003) and are evident in the work of groups such as the Public Conversations Project, the Public Dialogue Consortium, and the National Issues Forum (see Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997).

Although rich and intuitively appealing, postmodern constructivism has been criticized for its abstract intellectualism (Alvesson and Willmott, 1992a, 1992b) and its tendency to denigrate and alienate the elite (Voronov and Coleman, 2003). Critics find its central ideas and jargon vague and difficult to operationalize in any useful manner: it seems to find meaning-making processes and dominance everywhere but makes it difficult to pinpoint them anywhere. It has also been chided for its overemphasis on the subjective and denial of the importance of objective circumstances.

Although this approach is intriguing, the level of consciousness required with it can be quite demanding and difficult to sustain, even under nonthreatening conditions (Kegan, 1994). Therefore, the possibilities of applying such methods in situations of intense, protracted conflict are particularly challenging.

The Systems Paradigm

In essence, the system’s perspective is based on an image of a simple living cell developing and surviving within its natural environment. A biological metaphor, it views conflicts as living entities made up of a variety of interdependent and interactive elements that are nested within other, increasingly complex entities. Thus, a marital conflict is nested within a family, a community, a region, a culture, and so on. The elements of systems are not related to one another in a linear manner but interact according to a nonlinear, recursive process so that each element influences the others. In other words, a change in any one element in a system does not necessarily constitute a proportional change in others; such changes cannot be separated from the values of the various other elements that constitute the system. Thus, intractable conflicts are viewed as destructive patterns of social systems, which are the result of a multitude of different hostile elements interacting at different levels over time, culminating in an ongoing state of intractability (see Ricigliano, 2012; Burns, 2007; Körppen, Ropers, and Giessmann, 2011). Power and influence in these systems are multiply determined, and substantial change is thought to occur only through transformative shifts in the deep structure or pattern of organization of the system.

Ironically, the systems orientation is one of the most common and yet least well developed of the conflict paradigms. Its approach encourages us to see the whole. It presents the political, the relational, the pathological, and the epistemological as simply different elements of the living system of the conflict. Thus, it stresses the interdependent nature of the various objectives in intervention of mutual security, stability, equality, justice, cooperation, humanization of the other, reconciliation, tolerance of difference, containment of tension and violence, compatibility and complexity of meaning, healing, and reconstruction. It suggests that through the weaving and sequencing of such complementary approaches, it may be possible to trigger shifts in the deep structure of systems like Northern Ireland, Cyprus, Israel-Palestine, or Sudan in a manner that may produce a sustained pattern of transformational change.

However, a great deal of work must be done for this worldview to become useful at an operational level. General systems theory has been criticized for its lack of specificity, imprecise definition, and contributing relatively little to the generation of testable hypotheses in the social sciences (Kozlowski and Klein, 2000). In addition, its emphasis on homeostasis and equilibrium in systems, while important, neglects the critical temporal dimension: how conflict systems change and evolve over time (Nowak and Vallacher, 1998). Work from this perspective will need to move beyond its use as a general heuristic in order for it to realize its full potential to address complex social conflicts.

* * *

These five paradigms and various associated procedures provide us with an extensive menu of perspectives and options for addressing intractable social conflicts. Each approach is supported to some degree by empirical research, and each offers a unique problematique, or system of questioning, that governs the way we think about intervention in conflicts. However, each paradigm is also aspectual: orienting our focus toward certain aspects of conflict and away from others. Ideally we must develop a capacity to conceptualize and address intractable conflicts in a manner that is mindful of the complementarities and limits of these diverse approaches.

COMPONENTS OF INTRACTABLE CONFLICTS

What makes intractable conflicts persist? Scholars have identified a diverse and complex array of interrelated factors that help distinguish between tractable and intractable conflicts (Coleman, 2003). Of course, all conflicts are unique, and it may not always be useful to compare, say, moral conflicts with intractable conflicts over territory or water rights, or conflicts between a husband and wife in the United States with those between a powerful majority group and members of a low-power group in East Asia. However, despite the many differences that arise in such comparisons, we suggest that intractable conflicts, particularly if they have persisted for some time, share to some degree some or all of the following characteristics related to their context, core issues, relations, processes, and outcomes.

Context

Many peace scholars have emphasized the importance of structural variables embedded in the context of protracted conflicts as the primary source of their persistence.

Legacies of Dominance and Injustice.

Intractable conflicts regularly occur in situations where there exists a severe imbalance of power between the parties in which the more powerful exploit, control, or abuse the less powerful. Often the power holders in such settings use the existence of salient intergroup distinctions (such as ethnicity or class) as a means of maintaining or strengthening their power base (Staub, 2001). Many of these conflicts are rooted in a history of colonialism, ethnocentrism, racism, sexism, or human rights abuses in the relations between the disputants (Azar, 1990). These legacies manifest in ideologies and practices at the cultural, structural, and relational levels of these conflicts, which act to maintain hierarchical relations and injustices and thereby perpetuate conflict.

Instability.

When circumstances bring about substantial changes, they can rupture a basic sense of stability and cause great disturbances within a system. This is true whether it is the divorce of two parents, the failure of a state, or the collapse of a superpower. Under these conditions, conflict may surface because of shifts in the balance (or imbalance) of power between disputants or because of increased ambiguity about relative power (Pruitt and Kim, 2004). It can also emerge when a sense of relative deprivation arises out of changes in aspirations, expectations, or achievable outcomes of the parties (Gurr, 1970, 2000). Such changes can bring into question the old rules, patterns, and institutions that have failed to meet basic needs and can decrease the level of trust in fairness-creating and conflict-resolving procedures, laws, and institutions, adversely affecting their capacity to address problems and further destabilizing the situation. Anarchical situations, where there is a lack of an overarching political authority or of the necessary checks and balances that help manage systems, are an extreme example of power vacuums that can foster protracted conflict.

Core Issues

Other peace scholars highlight the unique nature of the issues as the main driver of intractability.

Human and Social Polarities.

Tractable conflicts by definition involve resolvable problems that can be integrated, divided, or otherwise negotiated to the relative satisfaction of a majority of the parties. As such, they have a finite beginning, middle, and end. Intractable conflicts often revolve around some of the more central dilemmas of human and social existence that are not resolvable in the traditional sense. These are polarities (structured contradictions) based on opposing human needs, tendencies, principles, or processes, which have a paradoxical reaction to most attempts to “solve” them. These can include dilemmas over change and stability, interdependence and security, inclusive and efficient decision making, and individual and group rights (Coleman, 2003).

Symbolism and Ideology.

Intractable conflicts tend to involve issues with a depth of meaning, centrality, and interconnectedness with other issues that give them a pervasive quality (Rouhana and Bar-Tal, 1998). The tangible issues (e.g., land, money, water rights) that trigger hostilities in these settings are largely important because of the symbolic meaning that they carry or that is constructed and assigned to them. For instance, Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem in 2000 was seen as a frivolous gesture to some and as a flagrant attack on Islam to others. In Kashmi, much of the mountainous territory in dispute is frozen, uninhabitable wasteland, yet soldiers and civilians die each day to secure it. Such specific issues (resources, actions, and events) become symbols of great emotional importance through social interaction between people and through their connection to existing conflict narratives: stories that define the criteria for what is good, moral, and right in any given conflict setting (Bar-Tal, 2000).

Relationships

In addition, a subset of the field has focused on the central nature of the relations between disputants as basic to their enduring quality.

Exclusive and Inescapable.

In many intractable conflicts, the relations between the parties develop in settings where exclusive social structures limit intergroup contact and isolate the in-group across family, work, and community domains. This lack of contact facilitates the development of abstract, stereotypical images of the other, autistic hostilities, and intergroup violence (Deutsch, 1973; Varshney, 2002). However, the relationships are also typically experienced as inescapable by the parties, where they see no way of extricating themselves without becoming vulnerable to an unacceptable loss. This may be due to a variety of constraints, including geographical, financial, moral, or psychological factors. When destructive conflicts persist under these conditions, they tend to damage or destroy the trust, faith, and cooperative potential necessary for constructive or tolerant relations. In such relationships, the negative aspects remain salient, and any positive encounters are forgotten or viewed with suspicion and misconstrued as aberrations or attempts at deception.

Oppositional Group Identities.

As group conflicts escalate, opposing groups become increasingly polarized through in-group discourse and out-group hostilities, resulting in the development of oppositional identities constructed around a negation and disparagement of the out-group (Kelman, 1999). This is particularly likely with collective identities of ascribed statuses (such as family, sex, racial, and national group membership) where there is a long-term emotional attachment to the group that is unalterable and significant. When such group identities are subject to discrimination or oppression (and such treatment is viewed as unjust), protracted conflicts are likely to manifest and persist. These group memberships can provide members with an important sense of mutual respect, a meaningful understanding of the social world, and a sense of collective efficacy and agency. However, deep investments in these polarized identities can become a primary obstacle to constructive forms of conflict engagement and sustainable peace.

Intense Internal Dynamics.

Conflict is more likely to be resolvable when it (1) concerns conscious needs and motives, (2) is between unified groups or between individuals with little ambivalence regarding resolution, and (3) is over overt issues that can be explicitly detailed and addressed. As such, the conflictual intrapsychic and intragroup dynamics and hidden agendas associated with intractable conflicts contribute to their difficult nature. They typically consist of both implicit and explicit issues, formal and informal agendas, and deliberate and unconscious processes. In addition, the high degree of threat, harm, and anxiety associated with them leads to a felt need for defensiveness and secrecy, which drives many motives, issues, and actions underground.

Processes

The negative, highly emotional, and pervasive nature of the interactive processes of protracted conflicts have also been studied.

Strong Emotionality.

Economically rational models of costs and benefits or positions and interests cannot begin to model the fabric of protracted social conflicts. These processes have a boiling emotional core, replete with humiliation, frustration, rage, threat, and resentment between groups and deep feelings of pride, esteem, dignity, and identification within groups. In fact, some scholars contend that extreme reactions seen in conflicts are primarily based in emotional responses (Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997). In effect, the overall distinction between emotionality and rationality may be rather dubious when it comes to intractable conflicts, where they are often inseparable. Here, indignation, rage, and righteousness are reasons enough for retributive action. However, it is not merely the type and depth of emotions that distinguish tractable from intractable conflict, but rather differences in the normative structures and processes that imbue them with meaning. Our feelings of raw emotion (hate, rage, pride) are often labeled, understood, and acted on in ways shaped by rules and norms that define what certain emotions mean, whether they are good or bad, and how people should respond to them. Thus, similar emotions may be constructed and acted on differently in dissimilar families, communities, and cultures. Communities entrenched in an intractable conflict may unwittingly encourage emotional experiences and expressions of the most extreme nature, thereby escalating and sustaining the conflict.

Malignant Social Processes.

Over time, a variety of cognitive, moral, and behavioral processes combine to bring protracted conflicts to a level of high intensity and perceived intractability. They include such cognitive processes as stereotyping, ethnocentrism, selective perception (like the discovery of confirming evidence), self-fulfilling prophecies (when negative attitudes and perceptions impact the other’s behavior), and cognitive rigidity. These can fuel processes of deindividuation and dehumanization of the enemy, leading to moral disengagement and moral exclusion (Opotow, 1990), that is, the development of rigid moral boundaries between groups that exclude out-group members from typical standards of moral treatment. This can result in a variety of antagonistic behaviors such as escalatory spirals (where each aggressive behavior is met with a more aggressive response), autistic hostilities (a cessation of direct communication), and violence. What is unique to intractable conflicts is the pervasiveness and persistence of psychological and physical violence, how it typically leads to counterviolence and some degree of normalization of violent acts, and the extreme level of destruction it typically inflicts. These escalatory processes culminate in the development of malignant social relations, which Deutsch (1985) described as a stage (of escalation) “which is increasingly dangerous and costly and from which the participants see no way of extricating themselves without becoming vulnerable to an unacceptable loss in a value central to their self-identities or self-esteem” (p. 263).

Pervasiveness, Complexity, and Flux.

Tractable conflicts have relatively clear boundaries that delineate what they are and are not about, whom they concern and whom they do not, and when and where it is appropriate to engage in the conflict. In intractable situations, the experience of threat associated with the conflict is so basic that the effects of the conflict spread and become pervasive, affecting many aspects of a person’s or a community’s social and political life (Rouhana and Bar-Tal, 1998). The existential nature of these conflicts can affect everything from policymaking, leadership, education, the arts, and scholarly inquiry down to the most mundane decisions such as whether to shop and eat in public places. The totality of such experiences feels impenetrable. Yet they are systems in a constant state of flux. Thus, the hot issues in the conflict, the levels where they manifest, the critical parties involved, the nature of the relationships in the network, the degree of intensity of the conflict, and the level of attention it attracts from bystander communities are all subject to change. This chaotic, mercurial character contributes to their resistance to resolution.

Outcomes

Finally, the outcomes of many intractable disputes in turn establish the conditions that contribute to their persistence.

Protracted Trauma.

The experience of prolonged trauma associated with these conflicts produces what is perhaps their most troubling consequences. Long-term exposure to atrocities and human suffering, the loss of loved-ones, rape, bodily disfigurement, and chronic health problems can destroy people’s spirit and impair their capacity to lead a healthy life. At its core, trauma is a loss of trust in a safe and predictable world. In response, individuals suffer from a variety of symptoms, including recurrent nightmares, suicidal thoughts, demoralization, helplessness, hopelessness, anxiety, depression, somatic illnesses, sleeplessness, and feelings of isolation and meaninglessness. Trauma adversely affects parenting, marriages, essential life choices, and the manner with which authority figures take up leadership roles. It also impairs communities and can hamper everything from the most mundane merchant-client interactions to voting and governmental functioning (Parakrama, 2001). Thus, the links between trauma and intractability seem to lie in the degree of impairment of individuals and communities and, in particular, to the manner in which trauma is or is not addressed postconflict.

Normalization of Hostility and Violence.

In these settings, destructive processes gradually come to be experienced as normative by the parties involved. The biased construction of history, ongoing violent discourse, and intergenerational perpetuation of the conflict contribute to a sense of reality where the hostilities are as natural as the landscape. For example, Israeli and Palestinian youth in the Middle East were found to accept and justify the use of violence and war in conflict significantly more than youth from European settings of nonintractable conflict (Orr, Sagi, and Bar-On, 2000). In addition, they found Israeli and Palestinian youth more reluctant than Europeans to be willing to pay a price for peace. Again, what appeared to matter in this study was how the meaning of violence differed for the youth from these different settings. The violence-war discourse in the Middle East, passed down through the distinct parental and community ideologies of the Israeli and Palestinian communities, depicted violence as an act of self-defense and war as a noble cause. This type of ideology has been found to shield youth from the psychological harm typically associated with exposure to violence. Thus, increased levels of violence had become normalized for the Middle Eastern youth and were seen as necessary and useful particularly because of the perception that negotiations were impossibly costly (in terms of the nonnegotiable concessions that would need to be made).

Persistence.

What is particularly daunting about this 5 percent of protracted conflicts is their substantial resistance to good-faith attempts to solve them. In these settings, the traditional methods of diplomacy, negotiation, and mediation—even military victory—seem to have little impact on the persistence of the conflict. In fact, there is some evidence that these strategies may make matters worse (Diehl and Goertz, 2000).

* * *

To summarize, intractable conflicts are multiply determined, complex, mercurial, exhausting, and rife with misery. Their persistence can be the result of a wide variety of causes and processes. Ultimately, however, it is the complex interaction of these many factors across different levels of the conflict (from personal to international) over long periods of time that brings them to an extreme state of hopelessness and intransigence. Therefore, we must employ models that conceptualize and address them in a manner that is mindful of the many components and complex relationships inherent to the phenomenon. The dynamical-systems approach provides such a model.

A DYNAMICAL SYSTEMS MODEL OF INTRACTABLE CONFLICT

Conflict engagement is essentially about change. It revolves around a need or desire to address incompatibilities by changing a situation; a relationship; a balance of power; another’s actions, values, beliefs, or bargaining position; or a third party’s wish to change a conflict from high intensity to low or from destructive to constructive. Therefore, how we think about and approach change or, in the case of intractable conflicts, how we understand conflict systems that doggedly resist change is paramount. There are many theories of change, and disputants as well as conflict resolution practitioners all operate with respect to these theories, whether implicit or explicit, complex or simple, accurate or inaccurate (Coleman, 2004). Dynamical systems theory, a school of thought coming out of applied mathematics, offers new, highly original, and practical insights about how complex systems of all types, from cellular to social to planetary, change and resist change (for more detail, see Coleman, 2011; Coleman, Vallacher, Nowak, and Bui-Wrzosinska, 2007; Vallacher, Coleman, Nowak, and Bui-Wrzosinska, 2010; Vallacher et al., 2013).

A dynamical system is defined as a set of interconnected elements (such as beliefs, feelings, and behaviors) that change and evolve over time in accordance with simple rules. A change in each element depends on influences from other elements. Due to these mutual influences, the system as a whole evolves in time. Thus, the effects resulting from changes in any element of a conflict (such as level of hostilities) depend on rules-based influences of various other elements (e.g., each person’s motives, attitudes, actions) that evolve to affect the disputants’ general pattern of interactions (positive or negative). The task of dynamical systems research is to specify the nature of these rules and the system-level properties and behaviors that emerge from the repeated iteration of these rules. In recent years, the dynamical systems perspective has been adapted to investigate personal, interpersonal, and societal processes under the guise of “dynamical social psychology” (Nowak and Vallacher, 1998; Vallacher and Nowak, 1994, 2007). The most recent extension of this approach focuses on the defining features of intractable conflict (Coleman, 2011; Coleman, Vallacher, Nowak, and Bui-Wrzosinska, 2007; Nowak et al., 2006; Vallacher et al., 2010, 2013).

Intractable conflicts seem to operate and change differently from most other conflicts, according to their own unique set of rules. Think of epidemics, which do not spread like other outbreaks of illness that grow incrementally. Epidemics grow slowly at first until they hit a certain threshold, after which they grow catastrophically and spread exponentially. This is called nonlinear change. We suggest that the 5 percent of enduring conflicts operate in a similar manner. In these settings, many interrelated problems begin to collapse together and feed each other through reinforcing feedback loops, which eventually cross a threshold and become self-organizing (self-perpetuating) and therefore unresponsive to outside intervention. In the language of applied mathematics and dynamical systems theory, these conflict systems become attractors: strong, coherent patterns that draw people in and resist change. This, we suggest, is the essence of intractable conflict.

As a conflict evolves toward intractability, each party’s thoughts, feelings and actions—even those that seem irrelevant to the conflict—take on meaning that maintains or intensifies the conflict. Metaphorically, the attractor serves as a valley in the social-psychological landscape into which the psychological elements—thoughts, feelings and actions—begin to slide. Once trapped in such a valley, escape requires tremendous will and energy and may appear impossible to achieve.

Despite the self-destructive potential of entrenched conflict, attractors satisfy two basic social-psychological motives. First, they provide a coherent view of the conflict, including the character of the in-group, the nature of the relationship with the antagonistic party, the history of the conflict, and the legitimacy of claims of each party. This function of attractors is especially critical when the parties encounter information or actions that are open to interpretation. An attractor serves to disambiguate actions and interpret the relevance and true meaning of information. Second, attractors provide a stable platform for action, enabling parties to a conflict to respond unequivocally and without hesitation to a change in circumstances or an action initiated by other parties. In the absence of an attractor, the conflicting parties may experience hesitation in deciding what to do, or engage in internal dissent that could prevent each party from engaging in a clear and decisive course of action. Such hesitancy or indecision can have calamitous consequences in the context of violent conflicts.

This perspective provides a new way to conceptualize and address intractable conflict. Conflicts are commonly described in terms of their intensity, but this feature does not capture the issue of intractability. Even conflicts with a low level of intensity can become protracted and resistant to resolution. We propose instead that intractable conflicts are governed by strong attractors for negative dynamics and weak attractors for positive or even neutral dynamics. Hence, knowledge of the attractor landscape of a system—the ensemble of sustainable states for positive, neutral, and negative interactions—is critical for understanding the progression, stabilization, and transformation of intractable conflicts.

A relationship between conflicting parties may be characterized by incompatibilities with respect to many issues, but this state of affairs does not necessarily promote intractability. To the contrary, the complexity or multidimensionality of such relationships may prevent the progression toward intractability or even enhance the likelihood of conflict resolution. Because each party may lose on one issue but prevail on others, conflict resolution is tantamount to bartering or problem solving, with both parties attempting to find a solution that best satisfies their respective needs (Fisher, Ury, and Patton, 1992).

However, it is the collapse of complexity in relationships that promotes conflict intractability. When distinct issues become interlinked and mutually dependent, the activation of a single issue effectively activates all the other ones. The likelihood of finding a solution that satisfies all the issues thus correspondingly diminishes. For example, if a border incident occurs between neighboring nations with a history of conflict, there is likely to be a reactivation of all the provocations, perceived injustices, and conflicts of interest from the past. The parties to the conflict thus are likely to respond disproportionately to the magnitude of the instigating issue. Even if the instigating issue is somehow resolved, the activation of other issues will serve to maintain and even deepen the conflict.

The loss of issue complexity is directly linked to the development of attractors. Interpersonal and intergroup relations are typically multidimensional, with various mechanisms operating at different points in time, in different contexts, with respect to different issues, and often in a compensatory manner. The alignment of separate issues into a single dimension, however, establishes reinforcing feedback loops, such that the issues have a mutually reinforcing rather than a compensatory relationship. All events that are open to interpretation become construed in a similar fashion and promote a consistent pattern of behavior in relation to other people and groups. Even a peaceful overture by the out-group, for instance, may be seen as insincere or as a trick if there is strong reservoir of antagonism toward the out-group.

However, any psychological or social system is likely to have multiple attractors (e.g., love and indifference and hate in a close relationship), each providing a unique form of mental or behavioral coherence with different levels of stability and resistance to change. When the dynamics of a system is captured by one of its attractors, the others may not be visible to observers, perhaps not even to the participants. These latent attractors, though, may be highly important in the long run because they determine which states are possible for the system if and when conditions change. Critical changes in a system, then, might not be reflected in the system’s observable state but rather in the creation or destruction of a latent attractor representing a potential state that is currently invisible to all concerned.

Despite their considerable resistance to change, it is important to recognize that attractors for intractable conflict can and do change. There are three basic scenarios by which this seems to occur (Vallacher et al., 2010). In one, an understanding of how attractors are created can be used to reverse-engineer an intractable attractor. Attractors developed as separate elements (e.g., issues, events, pieces of information) become linked by reinforcing feedback to promote a global perspective and action orientation. Reverse engineering thus entails changing some of the feedback loops from reinforcing to inhibitory, thereby lowering the level of coherence in the system. A second scenario involves moving the system out of its manifest destructive attractor into a latent attractor that is defined in terms of benign or even positive thoughts, actions, and relationships. The third scenario goes beyond moving the system between its existing attractors to systematically changing the number and types of attractors. These three strategies are described in more detail in the guidelines in the next section.

Dynamical systems theory offers a new perspective and language through which to comprehend and address intractability. Its use requires a working understanding of the main constructs and relationships of complex dynamical systems, nonlinearity, feedback loops, attractors, latent attractors, repellers, emergence, self-organization, networks, and unintended consequences. (For more information, see Coleman, 2011; Vallacher et al., 2010, 2013.)

TEN GUIDELINES FOR ALTERING THE ATTRACTOR LANDSCAPES OF INTRACTABLE CONFLICTS

The dynamical systems model of intractable conflict has direct implications for practice (see Coleman, 2011, for a fuller account). Following are ten general guidelines for working with long-term conflicts that have emerged from this approach:

- Leverage instability

- Complicate to simplify

- Read the emotional reservoirs of the conflict

- Begin with what is working

- Beginnings matter most

- Circumvent the conflict

- Seek meek power

- Work with both manifest and latent attractors

- Alter conflict and peace attractors for the long term

- Restablize through dynamic adaptivity

Guideline 1: Leverage Instability

Intractable conflicts involve ultracoherent, closed systems that steadfastly resist many good-faith attempts at change. When such coherence and absolute certainty about us versus them provides the foundation for understanding and the platform for action in conflict, it is useful to leverage whatever is necessary to change the patterns. Here the challenge becomes what the organizational theorist Gareth Morgan (1997) refers to as “opening the door to instability.” This entails either capitalizing on existing conditions or creating new conditions that in fact destabilize the system.

For instance, in research by Diehl and Goetz (2000; see also Klein, Goertz, and Diehl, 2006) of the approximately 850 enduring international conflicts that occurred throughout the world between 1816 to 1992, over three-quarters of them were found to have ended within ten years of a major political shock (world wars, civil wars, significant changes in territory and power relations, regime change, independence movements, or transitions to democracy). From the perspective of Dynamical Systems Theory (DST), these shocks created fissures in the stability of the previous systems, eventually leading to the establishment of the necessary conditions for the major restructuring and realignment of conflict landscapes.

This suggests that events such as those erupting in the Middle East today (e.g., the Arab Spring) promote optimal conditions for a dramatic realignment of sociopolitical systems. Similarly, a family system plunged into crisis by the sudden announcement of divorce by the parents, a child’s diagnosis of terminal illness, a criminal conviction of a family member, or the need to quickly uproot and move out of state for work could all place a family system in a tenuous, high-anxiety state. Such shocks can destabilize protracted conflict systems and allow the deconstruction and reconstruction of the attractor landscape. However, the results of destabilization may take years to become evident, as the initial shock most likely affects factors that affect other factors and so on until overt changes occur. It is also important to note that such ruptures to the coherence and stability of sociopolitical systems do not ensure radical or constructive change or peace. It must therefore be considered a necessary but insufficient condition when working with intractability.

Guideline 2: Complicate to Simplify: Mapping the Dynamic Ecology of Peace and Conflict

A central task for intervenors working with intractable conflict is to avoid premature oversimplification of the problems they face and to identify and work through key elements of the system that are driving or constraining change in a manner informed by the complexities of the situation. Consequently, one of the first challenges for intervenors working in a system with a collapse of complexity (strong us-versus-them polarization dynamics) is to maintain or enhance their own and the disputants’ tolerance for ambiguity, contradiction, and sense of integrative complexity with regard to the case (Coleman, Redding, and Ng, forthcoming; Conway, Suedfeld, and Tetlock, 2001). This includes the capacities to tolerate ambiguous and contradictory information and to view the system holistically; to begin to see different aspects of the problem and how they relate to one another and then to put this information together in a manner that informs action. This is no small task under the pressures and constraints of intense, long-term conflict. Coleman, Redding, and Ng (forthcoming) have developed a two-level framework to help assess and enhance these competencies in decision makers and disputants and to assess and foster the institutional conditions known to be conducive to them.

One increasingly useful and popular method of enhancing complexity is through conflict and peace mapping. Because destructive conflicts demand attention to the here and now—to the violence, hostilities, suffering, and grievances evident in the immediate context—they often draw attention away from the history, trajectory, and broader context in which the conflict is evolving. Today many peace practitioners employ the use of complexity and feedback-loop mapping to recontextualize their own and the stakeholders’ understanding of the conflict (see Burns, 2007; Coleman, 2011; Körppen et al., 2011; Ricigliano, 2012).

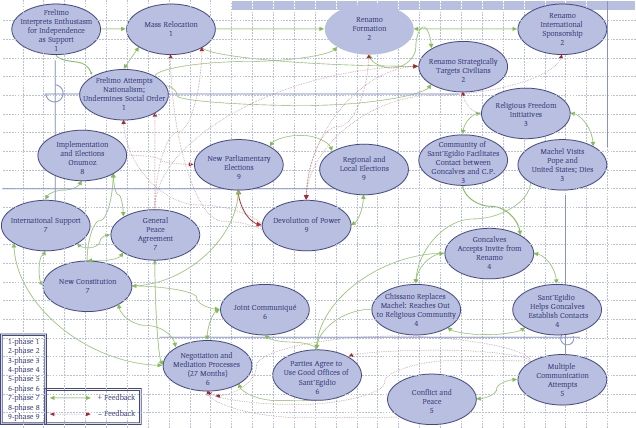

The dynamical system of the conflict, in the form of a dynamic network, can be represented through a series of feedback loop analyses (see figure 30.1 for a representation of the conflict and peace process in Mozambique in the 1980s and 1990s). Loop analysis, developed by Maruyama (1963, 1982), is useful for mapping reinforcing and inhibiting feedback processes that escalate, de-escalate, and stabilize destructive conflicts. Reinforcing feedback occurs when one element (such as a hostile act) stimulates another element (such as negative out-group beliefs) along its current trajectory. Inhibiting feedback occurs when one element inhibits or reverses the direction of another element (such as when guilty or compassionate feelings damper hostilities). Strong attractors are created when reinforcing feedback loops are formed between previously unrelated elements while inhibiting feedback dissipates in the system.

Figure 30.1 Feedback Loop Analysis of Mozambique Conflict and Peace

Source: Coleman, P. T., Vallacher, R., Nowak, A., Bui-Wrzosinska, L., and Bartoli, A. (2011). Navigating the landscape of conflict: Applications of dynamical systems theory to protracted social conflict. In N. Ropers (Ed.), Systemic thinking and conflict transformation . Berlin: Berghof Foundation for Peace Support.

Feedback mapping not only captures the multiple sources and complex temporal dynamics of conflict systems but can also help identify central nodes and patterns that are unrecognizable by other means. The process typically begins by identifying the key elements in the conflict that emerge during different phases of escalation and specifying the nature of the linkages among these elements. This analysis can be characterized as evolving through various developmental stages (such as phases 1 to 9 in figure 30.1 ). Maps can be generated at the individual level (identifying the emotional and cognitive links that parties hold in their attitudes, feelings and beliefs—associations related to the problem and to their sense of the other), the interpersonal level (allies, enemies, power structures and so on), and the systemic level (e.g., mapping the feedback loops that allowed a particular series of events to escalate, such as seen in figure 30.1 ). This can be useful for remaining mindful of the systemic context of the conflict and restoring a sense of complexity into the parties’ understanding of events.

Feedback mapping can be particularly useful for identifying and understanding the more constructive or functional aspects of social systems. Merely asking stakeholders, “Why doesn’t the conflict get worse?” “Why did disputants settle in the past?” or “What provides a sense of hope today?” can orient the analysis toward more constructive components or dynamics of the system, as can asking, “Where are the islands of agreement or the networks of effective action today?” or “What type of taboos exist for destruction and violence here [places of worship, children, hospitals]?” This information, which is typically ignored in conflict analysis, can help reveal the system’s own autoimmune system that operates to inhibit the conflict.

Conflict maps can be generated alone as a prenegotiation exercise (with minimal training), with the help of facilitators or mediators, or in small groups of stakeholders. With conflict mapping, the goal is not necessarily to get it right. The goal at this stage is to get it different, that is, to try to reintroduce a sense of nuance and complexity into the stakeholders’ understanding of the conflict. The goal is to try to open up the system: to provide opportunities to explore and develop multiple perspectives, emotions, ideas, narratives, and identities and foster an increased sense of emotional and behavioral flexibility.

However, feedback loop mapping can result in extremely complex visualizations of a conflict’s dynamics; therefore, it is critical to be able to offer strategies for subsequently focusing and simplifying. For instance, once a system is mapped, one can employ basic measures of network analysis and centrality to assess different qualities of the elements, such as their levels of in-degree (how many links or loops feed them), out-degree (whether they serve as a key source of stimulation or inhibition of the conflict for other nodes), and betweenness (the degree to which they are located between and therefore link other nodes; see Wasserman and Faust, 1994). This process can help to focus the analysis and manage the anxiety associated with the overwhelming sense of complexity of the system. However, it does so in a manner better informed by its complexity, history, and context.

Guideline 3: Read the Emotional Reservoirs of the Conflict

Emotions are not simply important considerations in intractable conflict; they are the issue as they set the stage for destructive or constructive perceptions, cognitions and interactions. In fact, research on emotions and decision making in patients with severe brain injuries found that when people lose the capacity to experience emotions, they also lose their ability to make important decisions (Bechara, 2004). Thus, emotions are not only relevant to our decisions; they are central to them.

Laboratory research on emotions and conflict dynamics tells a consistent tale; it is the ratio that matters (Gottman, Swanson, and Swanson, 2002; Kugler, Coleman, and Fuchs, 2011; Losada and Heaphy, 2004). It is not necessarily how negative or how positive people feel about each other that really matters in conflict; it is the ratio of their positivity to negativity over time. Studies show that healthy couples and functional, innovative work groups tend to have disagreements and experience some degree of negativity in their relationships. This is normal, and in fact people usually need to experience this in order to learn and develop in their relationships. However, these negative encounters must occur within the context of a sufficient reservoir of positivity for the relationships to be functional. And because negative encounters have such an inordinately strong impact on people and relationships, there have to be significantly more positive experiences to offset the negative ones. Scholars have found that disputants in ongoing relationships need somewhere between three and a half to five positive experiences for every negative one to keep the negative encounters from becoming harmful (Gottman et al., 2002; Kugler et al., 2011; Losada and Heaphy, 2004). They need to have enough emotional positivity in reserve. Without this, the negative encounters will accumulate (rapidly), helping to create and perpetuate wide and deep attractors for destructive relations—in other words, intractable conflicts.

Guideline 4: Begin with What Is Working

Conflict resolution practitioners tend to focus on identifying and solving problems. While important, this orientation tends to obstruct our view of what is already working or of existing opportunities for solutions. Nevertheless, virtually every conflict system, even the most dire, contains people and groups who, despite the dangers, are willing to reach out across the divide and work to foster dialogue and peace. These are what Laura Chasin calls networks of effective action (Pearce and Littlejohn, 1997) and Gabriella Blum (2007) labels islands of agreement . For example, Blum has found that during many protracted conflicts, the disputing parties often maintain areas in their relationship where they continue to communicate and cooperate despite the severity of the conflict. In international affairs, this can occur with some forms of trade, civilian exchanges, or medical care. In communities and organizations, these islands may emerge around personal or professional crises (e.g., a sick child), outside interests (mutual work on common causes), or by way of chains of communications through trusted third parties. Recognizing and bolstering such networks or islands can mitigate tensions and help to contain the conflict.

There are countless examples of this in the international arena: among Germans and Jews during the Nazi campaign in Europe during World War II, blacks and whites in South Africa in the 1980s, and today in places like Darfur, Somalia, Iran, and North Korea. These networks are often the centerpiece of latent constructive attractors for people and groups. During times of intense escalation, these people and groups may become temporarily inactive; they may even go underground. But they are often willing to reemerge when conditions allow, becoming fundamental players in the transformation of the system. Thus, early interventions should identify and engage with these individuals and networks carefully and work with them to help alleviate the constraints on their activities in a safe and feasible manner.

In addition, communities around the world usually have well-established taboos against committing particular forms of violence and aggression. In fact, archeological research suggests that communal taboos against violence have existed for the bulk of human existence and were a central feature of the prehistoric nomadic hunter-gatherer bands (Fry, 2006, 2007). Indeed, a key characteristic of peaceful groups and societies, both historically and today, is the presence of nonviolent values, norms, ideologies, and practices. To varying degrees, they all emphasize impulse control, tolerance, nonviolence, and concern for the welfare of others. These values, when extended to members of other groups, hold great potential for the prevention of violence and the peaceful resolution of conflict.

Guideline 5: Beginnings Matter Most

Research on nonlinear systems consistently shows that they are particularly sensitive to the initial conditions of the system. This means that beginnings matter. Studies in our Intractable Conflict Lab have found that how people feel during the first three minutes of their conversations over moral conflicts sets the emotional tone for the remainder of their discussions (Kugler et al., 2011). Gottman’s (2002) research on marriage has found similar effects: the first few minutes of a couple’s emotions in conflict are up to 90 percent predictive of their future encounters. Computer simulations of conflict dynamics suggest that even very slight differences in initial conditions can eventually make a big difference (Leibovitch et al., 2008). The effects of these small differences may not be visible at first, but they can trigger other changes that trigger other changes and so on over time, until they have a huge impact on the dynamics. These initial differences can be the result of various things: strong attitudes of the people coming in, their openness to dialogue or the level of complexity of their thinking, how the conversations are set up and facilitated, or the history of the disputants’ interactions together. But what is clear is that the initial encounters tend to matter more than whatever follows.

Guideline 6: Circumvent the Conflict

Recognizing that stakeholders in protracted conflicts often view peacemakers themselves as also being players in the theater of conflict, some intervenors attempt to work constructively in these settings by circumventing the conflict. The idea here is that a main reinforcing feedback loop of intractability is the fact that the destructiveness of the conflict exacerbates the very negativity and strife that created the conflict conditions in the first place and thereby perpetuates it. However, attempts to address these circumstances directly, in the context of a peace process, typically elicit resistance; they are seen as affecting the balance of power in the conflict (usually by supporting lower-power groups most affected by the conditions). Intervenors recognizing this will work to address these conditions of hardship, without making any connection whatsoever to the conflict or peace processes. To some degree, this is what many community and international development projects try to achieve. The difference is that this tactic targets the conditions seen as most directly feeding the conflict and requires that every attempt be made to divorce these initiatives from being associated with the peace process (Praszkier, Nowak, and Coleman, 2010). This unconflict resolution strategy can help address some of the negativity and misery associated with conflicts, without becoming incorporated (attracted) into the polarized good-versus-evil dynamics of the conflict.

Guideline 7: Seek Meek Power

Sometimes more direct intervention in a conflict is necessary. Intractable, entrenched patterns of destructive conflicts typically reject out of hand strong-arm attempts pressing for peace and stability or even less coercive approaches to statist diplomacy or third-party mediation. History provides countless examples of the UN, the United States, and other powerful outside parties failing to forge peace in enmity systems such as Israel-Palestine, Cyprus, and Kashmir. Nevertheless, peace sometimes does emerge out of long-term conflicts, and one path is through the power of powerlessness, that is, through the unique influence of people and groups with little formal or hard power (military might, economic incentives, legal or human rights justifications, and so on) but with relevant soft power (trustworthiness, moral authority, wisdom, kindness). Hard-power approaches in high-intensity conflicts tend to elicit greater resistance and intransigence from their targets. Meek-power third parties are at times able to weaken resistance to change by carefully introducing a sense of alternative courses of action, hope for change, or even a sense of questioning and doubt in the ultracertain status quo of us-versus-them conflicts. They can also begin to model and encourage more constructive means of conflict engagement such as shuttle diplomacy and indirect communications through negotiation chains.

The events in the Mozambique peace process in the 1990s provide an excellent example of the utility of meek power in strong systems. During the conflict, the internal coherence of the two hostile systems was very high. Ideologically, militarily, and politically, there was no communication and exchange between the systems. Change emerged at the margins through nonthreatening communication processes facilitated by the Community of Sant’Egidio, a Catholic lay organization that allowed some key actors in the enmity system to consider alternatives to the current status quo. This initial consideration was made possible by the “weaknesses” of the propositions and of the proponents.

Guideline 8: Work with Both Manifest and Latent Attractors

Understanding change requires comprehending how things change over time. Complex systems evidence both linear and nonlinear change, which operate at different timescales. Linear change means that a change in any one element (e.g., increased cooperation) results in a proportional change in another (more constructive conflict) in a relatively direct and immediate manner. However, the elements of complex, tightly coupled conflict systems such as those characteristic of intractable conflicts tend to interact in a nonlinear fashion. This means that a change in any one element does not necessarily constitute a proportional change in others; such changes cannot be separated from the values of the other elements that constitute the system. This has major implications for conflict transformation and peace building.

First, it is critical to recognize that a system’s (current) states and attractors change according to different timescales. Manifest conflicts can evidence dramatic and rapid changes in their states, from relatively peaceful states to violent ones, or from intensely destructive states to peaceful ones. This is seen when social processes move from one attractor pattern to another across what has been termed a threshold or tipping point (Gladwell, 2000). However, such changes in the current state of the conflict should not be confused with changes in the underlying attractor landscape. Attractors tend to develop more slowly and incrementally over time as a result of a host of relevant conditions and activities, although their presence may not become known for some time.

Second, latent attractors may be highly significant in the long run because they determine which states are possible for the system if and when conditions change. Critical changes in a system, then, might be reflected not in the system’s observable state but rather in the creation or destruction of a latent attractor representing a potential state that is currently invisible to all concerned. This is what the world witnessed during the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. Hostile relations had been obvious for decades between the two countries, but after perestroika, their relations moved rapidly into a more tolerant and constructive attractor, which had been present but latent during the Cold War. During destructive conflicts, negative attractors are usually visible and positive attractors are latent. During more peaceful times, positive attractors are visible and negative attractors become latent.

The potential for latent attractors has important implications for addressing intractable conflict (Coleman, Bui-Wrzosinska, Vallacher, and Nowak, 2006; Coleman et al., 2007; Nowak, Vallacher, Bui-Wrzosinska, and Coleman, 2006). For example, although such factors as objectification, dehumanization, and stereotyping of the out-group can promote intractable intergroup conflict (Coleman, 2003; Kriesberg, 2005), their impact may not be immediately apparent. Instead, they may create a latent attractor to which the system can abruptly switch in response to a provocation that is relatively minor, even trivial. By the same token, although efforts at conflict resolution and peace building may seem fruitless in the short run, they may create a latent positive attractor for intergroup relations, thereby establishing a potential dynamic to which the groups can suddenly switch if conditions permit. A latent positive attractor, then, can promote a rapid deescalation of conflict, even between groups with a long history of seemingly intractable conflict.

Guideline 9: Alter Conflict and Peace Attractors for the Long Term

Although people tend to believe that peaceful relations are the opposite of contentious ones, research has found that the potential for both are often simultaneously present in our lives (Gottman et al., 2002). Although we can usually attend to only one or the other, the underlying potential for both exists in many relationships. In fact, they tend to operate in ways that are mostly independent of one another. In other words, conflict and peace are not opposites; they are two prospective and independent ways of being and relating—two alternative realities. This suggests that people can be at war and at peace at the same time. Even during periods of intense fighting between divorcing couples, work colleagues, ethnic gangs, or Palestinians and Israelis, there exist hidden potentials in the relationships—latent attractors—that are in fact alternative tendencies for relating to one another (Coleman, 2011; Vallacher et al., 2010, 2013). We see evidence of this when people or groups move very quickly from caring for each other to despising one another, or when the opposite occurs.

The implication of latent attractors for both conflict or peace is that our actions in a conflict can have very different effects on three distinct aspects of the peace and conflict landscape: the current situation (the levels of hostility and harmony in relations right now), the longer-term potential for positive relations (positive attractors), and the longer-term potential for negative relations (negative attractors). This suggests that we need to develop separate but complementary strategies for (1) addressing the current state of a conflict, (2) increasing the probabilities for constructive relations between the parties in the future, and (3) decreasing the probabilities for destructive future encounters. Most attempts at addressing destructive conflict target numbers 1 and 3 but often neglect to increase the probability for future positive relations. But without sufficient attention to the bolstering of attractors for positive relations between parties, progress in addressing the conflict and eliminating future conflict will be only temporary.

For example, if there is a long history of interaction between disputants, there may be other potential patterns of mental, affective, and behavioral engagement, some of which foster positive intergroup relations. Accordingly, identifying and reinforcing latent (positive) attractors, not simply disassembling the manifest (negative) attractors, should be the aim of both conflict prevention and intervention. A classic approach to this is the identification or development of joint goals and identities in an attempt to establish a foundation of cooperation and eventually trust between parties (Sherif et al., 1961; Deutsch, 1973; Worchel, 1987). Thus, even if dialogue, reconciliation processes, trust-building activities, and conflict resolution initiatives appear to be largely ineffective in situations of protracted struggles, they may very well be acting to establish a sufficiently strong attractor for moral, humane forms of interactions that may provide the foundation for a stable, peaceful future. The gradual and long-term construction of a positive attractor may be imperceptible, but it prepares the ground for a positive state that would be impossible without these actions.