CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

TEACHING CONFLICT RESOLUTION SKILLS IN A WORKSHOP

a

Susan W. Coleman

Yaron Prywes

This chapter describes the Coleman Raider model, used to teach negotiation and mediation skills to adult learners. By making explicit our teaching philosophy, course objectives, and methods, we hope to stimulate discussion and research about how conflict resolution is taught. Although organizations around the world have invested significant financial resources on this topic, there has been little systematic research over the past decade on the pedagogy of conflict resolution or on the models and methods used to teach these skills (Movius, 2008; Raider, 1995). We first share six pedagogical insights derived from our practice that have come to underpin our training design. Then we discuss the objectives of the course as a whole and the learning activities in each of our seven training modules. We follow with some recommendations for social science researchers and theorists. We conclude with a postscript to the earlier editions that shares three recent examples in which modules from this conflict resolution training have been used in other interventions: intact team building, a collaborative inquiry, and an organizational mediation with leadership coaching.

INSIGHTS FROM PRACTICE

The first pedagogical insight is that each learner has a unique and implicit “theory of practice” for resolving conflicts. Each individual’s theory of practice has been developed over a lifetime, influenced by many factors, such as various individual differences, skills, and competencies (see part 3, Personal Differences, in this Handbook), as well as salient cultural and identity groups’ norms and values, and situational roles and hierarchies (see part 5, Culture and Conflict, in this Handbook).

Second, learners need both support and challenge to examine their own theory of practice. Intellectual and experiential comparison of competitive and collaborative processes can create challenging internal conflict for most learners. From our experience, learners experience two types of internal conflicts. The first is felt by those who embrace collaboration as an ideal and yet experience dissonance as they discover through course exercises how much of their own behavior is viewed by others and themselves as competitive, accommodating, or compromising. The second is felt by those who resist or reject collaboration and then struggle when collaborative approaches appear to have some merit. Although the first group is typically larger, because most participants in our training are volunteers, the trainers must create a learning community where all feel safe enough to try on new skills and attitudes.

The third insight is that experiential exercises shift the responsibility for learning from the trainer to the participant. For many adult learners, role playing and subsequent public debriefing are powerful learning tools as well as unfreezing devices for behavioral and attitudinal change. The excitement, fun, and support of mutual self-discovery counteract the potential embarrassment of being less than perfect in front of the others.

Fourth, self-reflection based on video or audio feedback gives many learners motivation to modify problematic behavior. Videotaping or audiotaping the role-play exercise for later review enables each learner to observe and reflect on his or her own behavior in terms of general knowledge about the collaborative conflict resolution process presented by the trainers.

Fifth, user-friendly models and a common vocabulary enable a group of learners to talk about their shared in-program experience. Conceptual frames, like the ones taught in modules 2 through 7 (discussed in the next section), are broad enough to illuminate the underlying structure of a collaborative process across many contexts and cultures because they leave room for variation. The trainer needs to be contextually sensitive to explain and illustrate the heuristic frames in ways that are culturally and situationally relevant.

The final insight is that learners need follow-up and support after workshop training to internalize new concepts and skills. As in other areas of skills training, most participants need additional coaching in a supportive environment for behavioral change to occur (Raider, 1995). A three- to six-day workshop in conflict resolution can make the learner aware of what she does not know, thereby beginning the learning process, but more work is needed if a collaborative process is to become the preferred response to mixed-motive conflicts. This humbling but valid observation needs serious consideration by the conflict resolution field—by trainers as well as organizations that sponsor trainings.

OVERVIEW OF THE COLEMAN RAIDER WORKSHOP DESIGN

Developed by Ellen Raider and Susan Coleman, Conflict Resolution: Strategies for Collaborative Problem Solving is a highly interactive workshop typically conducted in a three- or six-day format. (It is based on Raider’s 1987 training manual, A Guide to International Negotiation .) The three-day format is for groups requesting training in collaborative negotiation. The longer format includes an extensive three-day module on mediation. All participants receive a training manual, which is divided into sections corresponding to the seven course modules:

- Module 1 presents an overview of conflict resolution, with an emphasis on distinguishing between competitive and collaborative resolution strategies.

- Module 2 introduces a structural model, the elements of negotiation. In this module, we focus on the difference between positions and needs or interests, as well as the skill of reframing and the use of a prenegotiation planning tool.

- Module 3 describes five communications behaviors or tactics that are typically used during negotiations, and it emphasizes the difference between the intent and the impact of any communication.

- Module 4, combining the learning from the previous modules, gives the learner a sense of the flow of a collaborative negotiation by introducing a stage model.

- Module 5 describes how cultural differences affect the conflict resolution process.

- Module 6 helps participants understand and deal with emotions, which typically arise during interpersonal and intercultural conflict.

- Module 7 in its short form introduces mediation as an alternative if negotiation breaks down. The longer form teaches participants the general skill and practice of mediation.

Although the information contained in these seven modules is the foundation for every workshop, the material presented is customized to meet the needs of each client. This is accomplished through selecting or creating case simulations, including previously recorded video examples of negotiations or mediations from our library, and prior assessments of the trainee group.

This precourse assessment and customization is an important part of our work. During the assessment, the training team builds rapport with the client and discovers many of the conflicting issues currently in the client’s system. This information enables the team to anticipate, recognize, and then incorporate relevant teachable moments during the training, that is, to link the training material to real concerns of the learners as they emerge. In this way, we have been able to teach this course to such diverse groups as schoolteachers in New York, Dallas, and Skopje; corporate executives in Buenos Aires, Paris, and Tokyo; grassroots community groups dealing with tenant organizing and environmental justice; diplomats from the Association of South-East Asian Nations and the European Union; and United Nations staff throughout the world. The course has been taught over the past twelve years to over ten thousand people. The materials have been translated into French, Spanish, Arabic, and Macedonian, and a book based on our manual has been published in Japanese.

WORKSHOP OBJECTIVES AND PEDAGOGY

Like other educators, we find it useful to identify for ourselves specific knowledge, skills, and attitude objectives for the training.

Knowledge Objectives

A glance at the Contents of this Handbook indicates the many areas of academic inquiry that affect the study of conflict and its resolution. How much of this body of knowledge can be included in an introductory experiential workshop?

We have decided to emphasize the distinction between competitive and collaborative approaches to conflict resolution (see chapter 1). Thus, we want participants to understand conceptually and experientially why and under what conditions cooperative conflict resolution processes such as collaborative negotiation and mediation are a better choice for individuals and society than are the commonly used strategies of competition and avoidance. Although we make it clear that we value cooperation, we also believe that we must not impose it on others. Our pedagogy encourages participants to try on this new paradigm to see if it is useful. Ultimately each participant must be self-motivated to make meaningful changes in his or her conflict-resolving behavior. We hope to provide information and experiences during our training that foster this exploration.

Through short essays in the training manual and minilectures, the trainers highlight and summarize in nontechnical language key insights from the field. In graduate courses at Columbia University and other institutions, we have supplemented these essays and lectures with additional assigned readings. Although specific knowledge objectives are associated with each module, there are some global knowledge objectives for the course:

- To develop an understanding that conflict is a natural and necessary part of life and that how one responds to conflict determines if the outcomes are constructive or destructive

- To develop awareness that competition and collaboration are the two main strategies for resolving conflict and for negotiation

- To develop awareness of one’s own tendencies in thinking about and responding to conflict

- To become a better conflict manager—in other words, to know which conflict resolution method is best suited for a particular conflict problem (e.g., avoidance, negotiation, mediation, arbitration, litigation, or force)

- To become aware of how critical it is to the process of constructive conflict resolution to share information about one’s own perspective without attacking the other and to listen and work to understand the perspective of the other side

Skills Objectives

The most fundamental skills objectives of our training are the following:

- To effectively distinguish positions from needs or interests

- To reframe a conflict so that it can be seen as a mutual problem to be resolved collaboratively

- To distinguish threats, justifications, positions, needs, and feelings and to be able to communicate one’s perspective using these distinctions

- To ask open-ended questions in a manner that elicits the needs, rather than the defenses, of the other and, by so doing, communicate a desire to engage in a process of mutual need satisfaction

- When under attack, to be able to listen to the other and reflect back the other’s needs or interests behind the attack

- To create a collaborative climate through the use of informing, opening, and uniting behaviors

Attitude Objectives

The shifts in attitude and awareness that we intend to support are a little harder to enumerate succinctly. We hope that each participant leaves the program believing that collaborative conflict resolution skills are useful in their own lives. We hope that they commit to the larger goal of increasing the use of cooperative conflict resolution skills at all levels to create a more caring and just society. We want people to leave with a greater sense of humility or “conscious incompetence”—an awareness that there is always room to improve their conflict negotiation skills and that improvement will not only make their lives better but will enhance the lives of those around them. We want participants to be aware of the pervasiveness of identity-based conflict and to increase their own sense of humility to counter the self-righteousness and dangerous fundamentalism that has grown so exponentially in our time. In short, we want them to leave owning their part.

In a similar vein, we want participants to leave with an appreciation of difference as a source of richness rather than a liability. We want them to be intrigued by the multiple perspectives that human beings from around the globe can have about the same event and the multiple possibilities there are for misunderstanding. While we want to excite and motivate, we also want to avoid the Pollyanna effect with participants underestimating just how difficult it can be to use these skills. In most of our programs, participants are returning to systems that are not predominantly collaborative. They will likely encounter managers and colleagues who may very well not support them in their use of collaborative conflict management skills. We want them to leave ready and wanting to do the hard work and be realistic about how difficult it might be.

Our process permits exploring this continuum through whole-group and small-group discussions and reflection through personal journaling. This investigation varies in depth and breadth depending on the specific audience and the time available for the training.

SEVEN WORKSHOP MODULES

With this overall learning perspective in mind, we present a description of the seven modules of the Coleman Raider workshop training with pedagogical commentary. Focus on each of the seven modules in the training sequence is adjusted according to the learning objectives of the audience.

Module 1: Overview of Conflict

The first module presents an overview of conflict. The focus is on exploring the participants’ attitudes. The exercises chosen are intended to create internal conflict within each participant, so that each examines his or her own attitudes toward conflict, competition, and collaboration. The main activities are a diagnostic case, a physical game, and an interactive video-based minilecture illustrating various methods of conflict resolution.

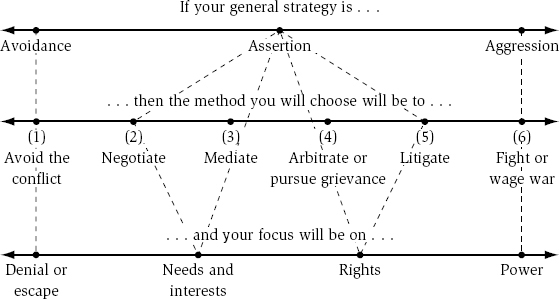

Collaborative negotiation and mediation are introduced by locating them along the spectrum of conflict resolution approaches that range from avoidance to war. Both negotiation and mediation are explained as consensual alternatives that focus on the parties’ underlying needs and interests and require their buy-in to try to reach an agreement. This is contrasted with quasi-judicial and power-based methods such as arbitration, litigation, or war. (See figure 35.1 .) In the minilecture we connect these strategies to important theories, such as Deutsch’s Crude Law of Social Relations (see chapter 1) and the dual-concern model.

Figure 35.1 Coleman Raider Resolution Continuum

Source: Copyright © 1992, 1995 E. Raider and S. Coleman. Permission has been given for use in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution . Other use is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holder.

A diagnostic case is the first experiential learning exercise. Small groups of four to six people are divided in half to represent each side of the dispute. The groups negotiate for twenty-five minutes—competitively for ten minutes, then collaboratively for fifteen. A frequently used diagnostic situation, the Ossipila case, is a conflict between international developers who, with local government backing, want to strip-mine on the ancient farmland used by villagers (who have support from environmental groups).

The exercise is recorded on audio (or video) and played back to the small groups; it is also used in module 3 for an in-depth analysis of negotiation behavior. There is a short debriefing immediately after the exercise.

The diagnostic case serves six functions:

- It immediately draws in both skeptics and believers to our process.

- It generates a baseline assessment for participants to discern those specific skill areas they need to work on during the rest of the training.

- 3. It brings out the inherent discrepancy between what we propose and what participants are actually doing.

- It demonstrates that the learning exercises in the workshop are highly participatory.

- It allows learners to experience the difficulty of switching from one negotiation strategy to the other, as well as the possible consequences of each approach.

- It initiates a positive atmosphere of shared learning.

The power of this experience comes from the direct challenge to the participants’ views of competition and collaboration. As they listen to themselves and hear the group’s feedback, the participants contrast their behavior with their own implicit theories and self-perceptions. This creates a discomfort that is the pivotal stimulus for change during the training. We have found that even if people cognitively grasp the principles of collaboration and want to use them, many will still act out a competitive or avoidant orientation without further practice and motivation to change.

Module 2: The Elements of Negotiation

In module 2, the goal is to introduce a framework called the elements of negotiation, that serves as the underlying grammatical structure of a negotiation. Just as parsing a sentence for verbs, nouns, and adjectives fosters understanding in any language, so too understanding the elements of negotiation fosters analysis of a conflict prior to and during a negotiation. We identify six structural elements: worldview, climate, positions, needs and interests, reframing, and bargaining “chips” and “chops”:

- One’s deeply held beliefs, attitudes, and values comprise a worldview. They are derived from one’s culture, family, and other important groups with which one identifies. Worldview is a central component of identity. It is almost always nonnegotiable, although it can change over time.

- Climate is the mood of the negotiation. It reflects the competitive or collaborative orientation of the parties in the negotiation.

- Positions are the specific demands or requests made by each party as negotiation commences—the party’s preferred solution to the conflict. If someone is competitive in her orientation, she may inflate her position or state it as nonnegotiable. A collaborative approach requires positions that are specific, clear, and honest with respect to negotiability.

- Needs and interests are what each negotiating party is looking to satisfy. If the position is “what you want,” the need is “why you want it.” Collaboration sometimes requires sorting through layers of positions and needs to arrive at a place where both sides’ salient needs can be adequately addressed and met.

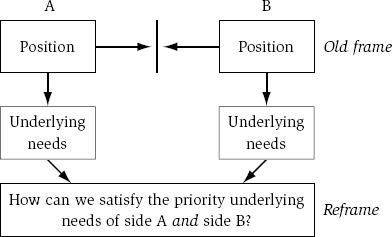

- Reframing is a way to refocus the conflict issue on needs, not positions. It is essentially the question, “How can we satisfy the priority needs of the parties to the conflict?”

- “Chips” and “chops” are, respectively, bargaining offers or threats that each side can use to influence the negotiation. Chips are positive need satisfiers that one side proposes so as to meet the needs of the other. They are effective only if perceived as valuable by the other party while also not undermining one’s own interests. Chops are negative need thwarters, such as threats or insults. They may be useful to counter threats or level a power imbalance between the disputants. However, they can encourage competition and undermine the trust needed for collaboration, so we discourage their use.

This shared frame of reference, with its common language, becomes a tool to make clear what the students often know intuitively. They learn to analyze the elements of each conflict presented and use this analysis to prepare for negotiation. A key learning goal is to be able to distinguish needs from positions and reframe conflict from a competitive clash of positions to collaboration based on understanding and acknowledgment of underlying needs and worldviews. The theoretical discussion underlying reframing in chapter 1 of this Handbook constitutes the intellectual context of our emphasis here. The main learning activities are analysis of simple or complex cases to practice recognition of needs, positions, and reframing (see figure 35.2 ) and use of the elements as a prenegotiation planning tool. We describe an example shortly.

Figure 35.2 Coleman Raider Reframing Formula

Source: Copyright © 1992, 1995 E. Raider and S. Coleman. Permission has been given for use in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution . Other use is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holder.

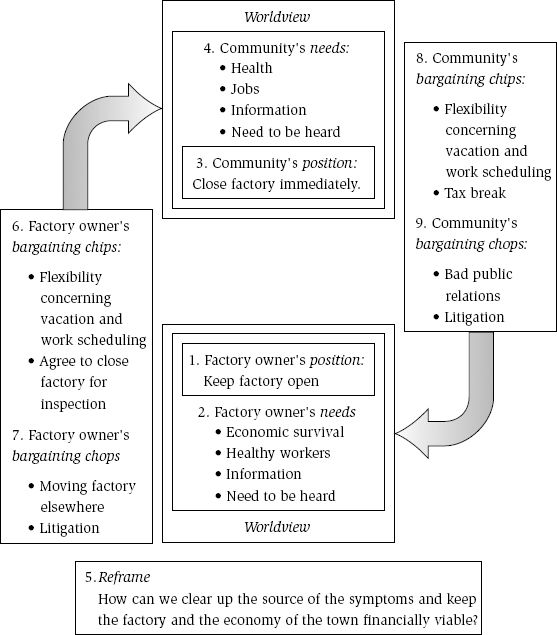

After a minilecture explaining the elements, the trainers lead the group through analysis (using a form similar to figure 35.3 , the negotiation planning form) of a conflict presented in two parts on video. Part 1 shows a heated conflict, and part 2 shows one possible resolution. Using a video to display the conflict grounds the discussion in a specific real-world context. The choice of which case to use is an important design decision and is made with understanding of its suitability for a particular client group. One case, A Community Dispute, has proved useful in many contexts, so we briefly describe it here to illustrate the definitions given earlier.

Figure 35.3 Coleman Raider Negotiation Planning Form: A Community Dialogue

Source: Copyright © 1992, 1995 E. Raider and S. Coleman. Permission has been given for use in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution . Other use is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holder.

The mayor of Centerville has called a meeting to address citizen complaints that a factory in the town is emitting powerful toxins that are causing respiratory illness. The owner of the chemical plant, the town’s main employer, is present, as are three members of Concerned Citizens of Centerville, made up of plant workers and community members. The mayor cautions that the cause of the illness is as yet undetermined but announces that the results of a preliminary environmental report require the factory to close for one week to see if it is the source of the problem.

As the video begins, it is not immediately clear whether this conflict is a clash of worldviews or an apparent conflict of interests. Assumptions abound, however, during class discussion. Is the factory owner a “greedy capitalist” unconcerned with the well-being of the town? Are the concerned citizens merely “environmental crazies” out to destroy the factory, as the owner implies? The workshop discussion generated by the ambiguity helps participants distinguish among position-, interest-, and identity-based conflict and to better understand the concept of worldview.

In part 1 of the video, the climate is hostile and competitive. The disputants interrupt, yell, contradict, and accuse one another, as well as make it clear that each side sees the other as unreasonable. The position of the community group is to close the factory immediately. The owner’s counterposition is to keep the factory open, and he asserts that his plant is not causing the infections.

Through analysis, the class members come to understand that the community needs health and jobs and that the owner needs to protect the economic viability of his factory and have healthy workers to run it. In addition, all have the need for accurate information about the source of the infections, as well as having their perspective acknowledged and understood. Much common ground is uncovered in what initially appears to some as a worldview clash. The rhetoric of the competitive climate simply makes it difficult to see what calm analysis reveals.

After part 1, the trainers lead the class in forming a reframing question. When they view part 2 of the video, they are able to compare their own reframe with the one used by the mayor: “How can we clear up the source of the symptoms and keep the factory and the economy of this town in good shape?”

In part 1, community members’ chops include the threat to take the environmental report to the local newspapers, thereby undermining the factory owner’s reputation and bottom line. Among the owner’s chops is the implied threat to move the factory to another town, taking jobs with him.

In part 2, after hearing the mayor’s reframing question, the group exchanges chips. At the psychological level, both sides listen to one another as they meet their mutual needs for respect and understanding. On the tangible level, the chips from the worker-and-community side are the workers’ willingness for them all to take paid vacation time during the same week in July and an agreement by the community to consider a tax break if the inspection finds that the factory is not the source of the problem. The factory owner’s chips include his willingness to close the factory for the inspection and to be flexible concerning the workers’ vacation and work scheduling.

After analyzing the video, the participants divide into pairs to continue practicing the skills of identifying positions and needs and forming reframes using a series of small cases. Through repetition, these drills pose the opportunity to try, err, and retry applying cognitive learning until learners thoroughly understand the skill. Mastery may or may not occur during the workshop. We hope that sufficient value and understanding are experienced so that the learning can continue to be practiced and applied in the participants’ lives.

The participants then use a similar format (see figure 35.3 ) as a planning tool for further conflict simulation. The planning process helps each party not only clarify its own side of the conflict but also begin to understand the other side better. We caution participants that identifying the other’s positions, needs, and so on can only reveal party A’s assumptions about party B and vice versa and that these assumptions must be tested during the upcoming negotiation. We also ask parties to think of all their chops, and those of the other, in this planning process so they can prepare not to use or react to them negatively, which would nullify the attempt to be collaborative.

Module 3: Communication Behaviors

In an ideal collaborative negotiation, each side thoroughly communicates its perspective and arrives at an understanding of the other side. In reality, the unique and particular worldviews of individuals and groups often make our interactions very complicated. Although two people speak the same language and know each other well, they may feel that they do not really understand one another. Furthermore, conflict can exacerbate misunderstanding. When our buttons are pushed, our ability to communicate can become quite imprecise and problematic.

To develop collaborative skills and enhance understanding of the communication process, we introduce a second frame, which is grounded in a research tool known as behavioral analysis (Rackham, 1993; Situation Management Systems, 1991). We identify five communication behaviors that occur during negotiation:

- 1. Attacking

- Evading

- Informing

- Opening

- Uniting

The mnemonic for these behaviors is the familiar English language vowel series AEIOU. These categories encompass nonverbal as well as verbal communications. We employ only these five types of communication behavior because they amount to an easily learned framework for understanding core communication behavior in conflict.

At the beginning of the module, the trainers present and role-play a two-line interchange. An example of a context-relevant miniskit frequently used with groups of managers is an employee reminding his boss about his upcoming vacation. Each time the interchange is repeated, the boss responds by demonstrating another behavior. The trainers elicit from the group a description of the kind of behavior they are observing. Then the trainers label the behavior:

- Attacking (A) is any type of behavior that the other side perceives as hostile or unfriendly: threatening, insulting, blaming, criticizing without being helpful, patronizing, stereotyping, interrupting, and discounting others’ ideas. It also includes nonverbal actions such as using a hostile tone of voice, facial expression, or gesture.

- Evading (E) occurs when one or both parties avoid facing any aspect of the problem. Hostile evasions include ignoring a question, changing the subject, not responding, leaving the scene, or failing to meet. Friendly or positive evasions include postponing difficult topics to deal with simple ones first, conferring with colleagues, and taking time out to think or obtain relevant information.

- Informing (I) is behavior that, directly or indirectly, explains one side’s perspective to the other in a nonattacking way. Information sharing can occur on many relevant levels: needs, feelings, values, positions, or justifications.

- Opening (O) invites the other party to share information. It includes asking questions about the other’s position, needs, feelings, and values (nonjudgmentally); listening carefully to what the other is saying; and testing one’s understanding by summarizing neutrally what is being said.

- Uniting (U) emphasizes the relationship between the disputants. This behavior sets and maintains the tone necessary for cooperation during the negotiation process. The four types of uniting behavior are (1) building rapport, (2) highlighting common ground, (3) reframing the conflict issues, and (4) linking bargaining chips to expressed needs.

After a presentation of AEIOU, the class returns to the small groups that were formed for the diagnostic case in module 1. The participants listen to the audio (or video) of the case. Together they fill in an AEIOU coding form (see table 35.1 for a summary of what is assessed) by identifying each comment as an attacking, evading, informing, opening, or uniting behavior. Within their groups, each member receives specific feedback on how his or her statements are perceived. Importantly, the type of behavior is identified by its impact on the receiver rather than by the intent of the speaker.

Table 35.1 Coleman Raider AEIOU Coding Sheet (Abridged)

Source: Copyright © 1992, 1997 E. Raider and S. Coleman. Permission has been given for use in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution . Other use is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holder.

| Negotiating Styles |

| Attack: threats, hostile tones or gestures, insults, criticizing, patronizing, stereotyping, blaming, challenging, discounting, interrupting, defending |

| Evade: ignore, change subject, withdraw, postpone, table issue, caucus |

| Inform: reasons, justifications, positions, requests, needs, underlying positions, feelings |

| Open: listen quietly, probe, ask questions nonjudgmentally, listen actively, paraphrase, summarize understanding |

| Unite: ritual sharing, rapport building, establish common ground, reframe, propose solutions, dialogue or brainstorming |

Each group has its own insights and, as a result, is often motivated to try new skills after people hear how they themselves sound. They also learn to give safe feedback by focusing on the impact the behavior has on them rather than assuming the intent of the sender. Self-awareness is heightened when a speaker finds that her actions have an unintended effect. This disparity gives her the opportunity to clarify or rectify her message. It also gives her a chance to think about how she generally comes across to others. It is clear from the debriefing of this exercise that the participants learn about the complexity of the communication process and its importance in maintaining a collaborative process.

We believe that for most trainees, this experiential learning is necessary, beyond cognitive understanding, for behavioral changes to take place. Multiple skills exercises combined with personal feedback motivate learners to produce the effort needed to change conflict behavior habits (Raider, 1995). Learners often describe this part of the course as a life-changing event. But because we know how difficult it is to integrate these skills and change one’s behavior, we believe that continued learning requires a supportive postworkshop environment, heightened self-motivation, and follow-up programs wherever possible. Empirical research into the long-term effect these workshops have on participants, in the context of supportive or resistive environments, would be very helpful.

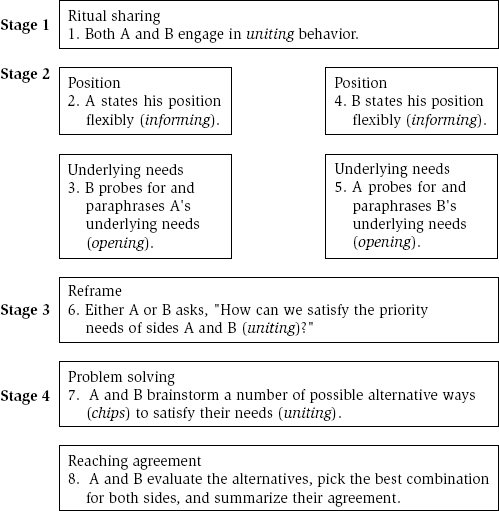

Module 4: Stages of the Negotiation

For life and for training purposes, we think it is useful to have a sense of the general order of an ideal collaborative negotiation. Although there is usually a back-and-forth flow to the negotiation process, it is useful to break it down into stages for training purposes. In module 4 we posit four stages:

- Ritual sharing

- Identifying the issues (positions and needs)

- Prioritizing issues and reframing

- Problem solving and reaching agreement

Although we present the stages linearly, we acknowledge that unless both parties want to be collaborative and are equally competent in collaborative skills, most real-life negotiations do not follow this simple pattern. However, this is not to say that they cannot.

The minilecture by the trainers starts this segment, using a video of a rehearsed bare-bones negotiation (see Figure 35.4 ): one in skeletal form that places each element and behavior in its ideal spot within the framework of the four stages.

Figure 35.4 Colman Raider “Bare-Bones” Model

Source: Copyright © 1992, 1995 E. Raider and S. Coleman. Permission has been given for use in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution . Other use is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holder.

Ritual sharing involves preliminary and often casual conversation to build rapport, establish common ground, and pick up critical background information (such as the other’s values), which may affect the negotiation. Uniting behavior predominates during this stage.

Identifying the issues has two phases: identifying the positions that frame the conflict and clarifying the needs that drive them. Informing and opening behaviors predominate during this phase, the first being used to tell where you are coming from and the second to understand the other.

Prioritizing issues and reframing has two parts. Prioritization is needed if there is more than one key issue and an order must be established (through a mininegotiation) for manageable problem solving. Reframing invites the parties to engage in creative problem solving around needs. It is characterized by a neutral and inclusive question, such as, “How can we satisfy the needs of A while also satisfying the needs of B?”

Problem solving and reaching agreement, the final stage, are characterized by brainstorming (using the informing, opening, and uniting behaviors) that facilitates fresh, novel solutions to the now shared problem. Humorous and even apparently absurd ideas are encouraged because they increase open-mindedness and often inspire clever solutions. Uniting and opening behaviors are used to diffuse any perceived attacks, highlight common ground, and reiterate the objective: to find mutually satisfying solutions. The negotiators then choose from the brainstormed list those solutions that are feasible and timely and that optimize the satisfaction of each party’s needs and concerns. Success depends in part on maintaining a continued collaborative, positive climate that encourages creativity.

As stated earlier, the trainers present the stages as a linear progression, but real-life negotiations rarely flow so predictably. A good negotiator develops the ability to identify the essence of each stage to diagnose whether the essential tasks embedded within it have been accomplished and to feel comfortable with the surface disorder. As certain needs are addressed, others may surface. Recognition and processing of all of these needs is necessary for a good and sustainable agreement.

After the stages have been covered, participants practice their own bare-bones negotiation. Trainers explain metaphorically that this is more like a map of the territory than the territory itself. As with maps, we must make a mental leap from a symbolic portrayal to what is seen when navigating the real landscape. The more clearly the underlying structure and process of bare bones are embedded in our thinking, the more effectively we as negotiators can deal with the variations that occur in actuality.

The bare-bones framework is the most prescriptive in our training. Therefore, great caution has to be used by the training team to make sure that examples used to illustrate this module are context relevant in form and substance, so that the model is seen as doable in various cultural contexts. The participants analyze conflict cases taken from their own lives and then present a skeletal and ritualized performance in front of the whole group. Each step is abbreviated, thus revealing whether the role players really understand the essence, or bare bones, of the conflict. The trainer coaches the role players and gives feedback at each point of the process. It is in this way that the role players and other participants begin to internalize all the previously learned material.

Module 5: Culture and Conflict

From its inception, our training model has woven the topic of culture throughout the process of teaching and learning negotiation skills. Our original audiences were made up of managers from multinational organizations eager to learn how to negotiate across borders. Building on the work of Weiss and Stripp (1985), Hofstede (1980, 1991, 2001), Ting-Toomey (1993, 1999, 2004), and others, we facilitated the trainees’ learning through readings, video clips (e.g., Griggs Productions, 1983; Wurzel, 1990, 2002;), and role plays to understand and internalize cultural variables such as high- or low-power distance, high- or low-communication context, individualism or collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and polychronic or monochronic time.

One role-play exercise has been particularly instructive and enjoyable for the participants. The group is divided into groups of four. One pair from the foursome is instructed to create a fictitious cultural ritual based on the Hofstede dimensions. The other pair comes to the role play unaware that they are entering a “new culture” and, as a result, experience a simulated form of culture shock as they interact with the classmates who have taken on different persona. The experience is videotaped and then reviewed by each foursome, with much laughter. The educational point is made that it is ideal to know the rules and norms of another culture and, at a minimum, to avoid negative judgments in order to have a successful negotiation.

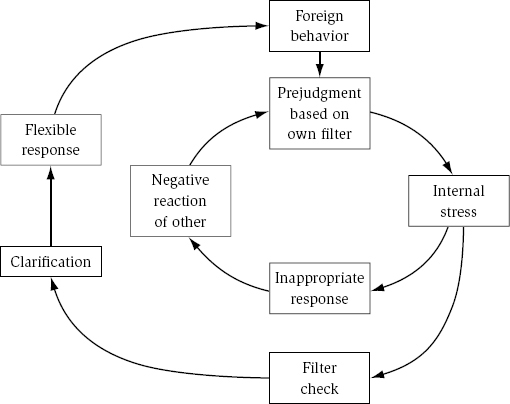

Video clips and exercises like this are debriefed by using our filter check model (see figure 35.5 ). For example, one of the video clips from Going International, Part Two shows a businessman from the United States (Mr. Thompson) waiting for his Mexican counterpart (Sr. Herrera) in an outdoor café in Mexico City. Mr. Thompson reacts negatively to the late arrival of Sr. Herrera (to whom he is trying to make a sale), apparently assuming the lateness is some form of disrespect or power play.

Figure 35.5 Coleman Raider Filter Check Model

Source: Copyright © 1992, 1995 E. Raider and S. Coleman. Permission has been given for use in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution . Other use is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holder.

The video captures elegantly and with humor how monochronic and polychronic individuals can misunderstand each other. 1 Sr. Herrera, the polychronic of the two, is late because he is greeting important people along the way. He also does not want to get down to business until he has gotten to know something about the man with whom he is doing business. Mr. Thompson, though, is driven by the task, always looking at his watch and pushing to get the contract signed—so then he can go out and have a good time!

By working through the filter check chart, participants come to see that the misunderstanding displayed is based on cultural assumptions (filters) of the meaning of time, task, and relationships. Neither way is the right way; they are just different. Of course, it is noted that “when in Rome, do as the Romans do,” and certainly so if you are in a lower power position, as a seller typically is relative to a buyer.

For audiences of educators, we use role-play simulations such as melting pot or salad bowl to surface issues of class, race, and gender. The disputants in this case are two groups: the Black Teachers Caucus (BTC) and the predominantly white school governance committee at an urban high school in New York City. (This case is based on a real conflict that Raider mediated; it is also discussed in the Introduction and chapter 1 of this Handbook.) The BTC demands a black seat on the governance committee, claiming that the student population is predominantly of color. The governance committee rejects this demand for a “race-based” seat, countering that representation should be by academic department, not by racial or ethnic identity group.

One way to use this case is to divide a group of four into sides A and B. In round 1 of the negotiation, each side presents its point of view, while the other side tries hard to listen and paraphrase the underlying needs it is hearing. In round 2, sides A and B switch and repeat the negotiation, following the model of constructive controversy (see chapter 4 in this Handbook). This technique helps not only to move the conflict toward resolution but to get participants to realize how difficult it is to step into the shoes of the other side. This technique might be unworkable if the gap in worldviews is too vast, perhaps due to the participants’ emotional attachment to the issues or their inability to take another’s perspective.

Module 6: Dealing with Anger and Other Emotions

To effectively work with emotions that arise during conflict, a negotiator must have good listening, communication, and problem-solving skills. This section outlines how these skills can be employed to direct emotions into a positive and productive component of the negotiation process. Anger is our main focus because it presents one of the biggest challenges to resolving conflict.

A Philosophy for Dealing with Anger.

The philosophy we present to participants is that if someone blames you, states his position inflexibly, confronts you, or attacks you:

- Avoid the defend-attack spiral and ethnocentric and egocentric responses. Assume that the other has a perspective different from yours and that you need to find out where he is coming from.

- 2. Listen actively. Your needs are more likely to be heard by the other if he knows through your active-listening behavior that you have understood his needs.

- Continue to change the climate from competition to cooperation by acknowledging that there are differing perspectives at play, each with part of the truth.

- Work with the other as a partner to solve the problem.

To build awareness on this topic, participants read an essay in the training manual covering such topics as the relationship of anger to unmet needs, anger as a secondary response that masks more vulnerable emotions, the attack-defend spiral, and additional destructive and constructive responses. Sometimes in the workshop, participants form groups of four to discuss the essay. Members offer examples from their own lives, sharing situations in which they themselves were angry or were dealing with another person’s anger.

Skills Practice.

A key exercise we use in building skills in this area is a round-robin, with one side of each negotiation team working competitively and the other collaboratively, and with one side moving from group to group and the other staying put. In the first round, the traveling partners are competitive. This means they can use attacking and evading behaviors to act angry, patronizing, and unfair. They are encouraged to make their attacks personal if possible. The stationary partners take on the role of skilled collaborative negotiators. They work to change the climate by using predominantly opening, and some uniting, behaviors to draw out the needs, feelings, and concerns of the others. This round lasts for ten minutes. The goal of the exercise is not to reach an agreement but simply to build readiness for negotiation by changing the climate. In the second round, all the traveling pairs rotate to the next table. The group reverses roles so that the stationary pair is now competitive and the traveling partners are collaborative. In the final round, the traveling pairs move to a third table, where a new foursome attempts to solve the conflict by having both sides use collaboration.

The whole group debriefs after each section so that the participants learn as they proceed. The rounds are often tape-recorded for review. The trainers guide the discussion with questions: “How did the emotions affect the process?” “Were the negotiators able to draw out emotions, unexpressed perspectives, and underlying needs?” “Were they able to create distance between the other’s position and needs in their paraphrases?” and, “What could they have done better?”

In this exercise, participants experience how difficult it can be to manage another’s attacks, emotions, and blaming behavior. Many acquire the insight that people have little control over someone else’s responses apart from developing their own collaborative skills. This is when they become “consciously incompetent”—beginning to know what they do not know. We consider this an important learning milestone because handling another’s anger is a common motivating concern for participants coming to the workshop. This exercise further motivates them to develop their own skills of listening and “going to the balcony,” or rising above the conflict to see it objectively from all perspectives (Ury, 1993).

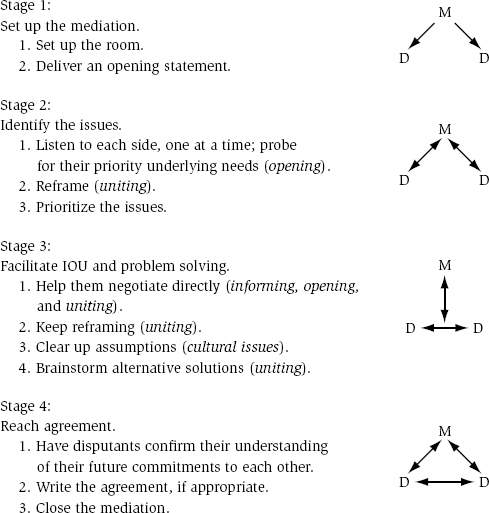

Module 7: Introduction to Mediation

In the Coleman Raider model, we often introduce a one-hour overview of mediation in our three-day workshop. The longer version teaches mediation skills. Here we briefly discuss the longer program (see figure 35.6 ).

Figure 35.6 Coleman Raider Meditation Model

Source: Copyright © 1992, 1995 E. Raider and S. Coleman. Permission has been given for use in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution . Other use is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holder.

The negotiation model already learned forms the framework for understanding mediation. We might move into the mediation segment of the program by asking participants to create a model for mediation based on what they already know about collaborative negotiation. This task is surprisingly simple as students realize how closely mediation is related to negotiation.

Participants are introduced to four stages of the mediation process (which almost parallel negotiation): (1) setting up the mediation, (2) identifying the issues, (3) facilitating informing, opening, and uniting (IOU) behaviors, and (4) problem solving and reaching agreement. The vehicles used to practice these stages are skill practice and role playing, the latter constituting the bulk of the activity.

The role plays offer the participants the opportunity to practice everything learned in both the negotiation and mediation segments of the course. Each mediation stage is practiced in trios, rotating the role of mediator. In debriefing, the mediator receives feedback from the trainers and the disputants themselves—how they felt the mediator moved or blocked the process and how specifically the mediator could have helped their role-play character. (For further discussion of mediation, see chapter 34 in this Handbook.) Cases are either furnished by the trainers or elicited from the audience. In addition to small-group mediations, trainers may facilitate the role plays in the center of the room, fishbowl style, with the class watching. Audio- or videotape is often used in various ways and in any segment of the program.

Throughout the program, trainers present numerous videos of experienced mediators, each with a distinctive style. These show differences in pacing, amount of questioning or silence, and a variety of techniques. The message we intend to impart is that there is no one right way to mediate. We present our model like training wheels on a bicycle: as soon as the learner-mediator grasps the process, he can begin to discover how to make it his own.

Relevant topics (such as caucusing, shuttle diplomacy, getting the parties to the table, organizational context, and culture) are discussed at intervals throughout the program. Prepared videos are used wherever available and relevant to elaborate on these topics and enrich the participants’ learning.

CONCLUSION

In this chapter, we have sought to give readers a sense of the theoretical underpinnings and pedagogical techniques used in our delivery of a conflict resolution training program. We have enumerated a number of insights, drawn from our years of practice, that inform our training designs. We have summarized the knowledge, skill, and attitude objectives we strive for in conducting the program. Finally, we have described in some detail the typical learning activities used in each module of the program.

We hope that sharing both what we have taught, as well as how we have taught it, will stimulate discussion as well as further research. More collaboration is needed with researchers to scientifically link training methods and content with resultant behaviors, along the lines of Peter Coleman and Ying Ying Lim’s pioneering study in 2001. In that study, they used a 360-degree feedback instrument to systematically examine the impact of this negotiation training on participants. One month following completion of the training, supervisors and subordinates reported more constructive outcomes to conflicts, and observers (who knew the participants well) also reported that participants used more uniting and informing behavior. Recently we have developed a conflict resolution 360-degree feedback instrument based on the AEIOU framework (Coleman and Raider, 2010), which could also be a tool that measures training impact in the future (http://cglobal.com/products/aeiou ).

POSTSCRIPT

As we have grown as practitioners who have delivered this training over many years, we have come to the conclusion that while this training is very powerful, it is generally insufficient when it comes to systemic change. When conflict resolution was emerging as a popular topic in the 1980s, training was the intervention of choice for both clients and practitioners. When there was tension, difficulty, or conflict, both practitioners and clients chose conflict resolution training. It was always helpful but not the tool that could ultimately make a systemic impact given its focus on the individual. Human behavior is a function of the person and the environment (Lewin, 1936), and unfortunately training often focuses only on building capacity at the individual and interpersonal levels. As a result, when participants return to work, they may not feel that the climate or context adequately supports them to practice their new awareness and skills. The danger is that participants revert to their old behaviors.

As we and our clients have evolved, so have the types of interventions that we suggest and that our clients allow. We offer three examples to illustrate this evolution. Each example uses the training in different ways: for intact team building, as part of a collaborative inquiry project, and as a component of an organizational mediation with leadership coaching. Future research could compare and contrast the impact these other interventions have in relation to that of traditional training—for example, whether they result in more or less conflict, closer working relationships, or greater organizational performance. Finally, each of the case study examples below is based on interviews with the authors and their colleagues.

Intact Team Building, by Krister Lowe

A regional headquarters of an international organization, located in the Caribbean, was struggling with conflict resulting from a slow leadership succession process. The region consisted of approximately fifty staff members and had been without an official leader for approximately one year. During that time, numerous divisions emerged among personnel related to the absence of clear direction from the top. The organization engaged me, as a conflict resolution specialist, in the hopes that they could get their house in order before a new leader was selected, which was set to occur in the coming months. The client and I agreed to conduct conflict resolution training, followed by a whole-system meeting, in order to give personnel both the skills and a forum to have constructive dialogue about the state of affairs. Since all staff members located in the regional office participated in the intervention, ranging from senior management to administrative support personnel, we called it an intact team-building initiative.

I split the staff into two groups of approximately twenty-five people each, so that half of the office could continue conducting business, while the other half received training. I then delivered two, two-day conflict resolution trainings back-to-back and brought the entire office together on a fifth, final day. Despite the logistical challenges, working with an intact team enabled me to influence the conflict culture within which the participants operated.

During the first four days of training, I encouraged the entire staff to focus on the individual and interpersonal levels of conflict. By the end of the four days, a climate of collaboration, consultation, and creativity emerged, such that when the fifth day arrived, the participants were primed for a discussion of group norms and culture. The group engaged in an honest and constructive dialogue, something that had been perceived as impossible earlier in the week. The group also engaged in collective group problem solving and convened in subunits to address insights at the team level of analysis. Following the week-long intervention, I provided one-on-one coaching to help resolve remaining disputes. In addition, a number of individuals requested coaching support; they realized they faced some long-standing intrapersonal conflicts and wanted to initiate a process of individual change.

In conclusion, in contrast to just delivering training, I had the privilege in this intervention of focusing on multiple systemic levels—individual, interpersonal, team, and regional office—all resulting in a shift in the climate and context within which the participants functioned. I witnessed how conflict resolution training for intact groups can create a climate for deeper reflection and systematic learning. The emotional nature inherent in the topic, if managed well, can segue into deeper, more longitudinal interventions that other training topics often do not create.

Collaborative Inquiry Project, by Sandra Hayes

A school approached me, an adult learning and development specialist, to facilitate improvements in teacher pedagogy to enhance student achievement. The client recognized that there might be differences among faculty, including different teacher and administrator perspectives, about how to improve pedagogy and wanted to create some good discussion. The client also wanted to test assumptions about who can achieve and in what context given that most of the educators were members of privileged groups (race, class) in contrast to their students.

We agreed to conduct two collaborative inquiry processes, one for teachers and one for administrators, to begin sharing perspectives on this complex topic. Collaborative inquiry is an innovative approach to action research that enables participants to address questions and challenges that matter to them most. Based on cycles of action and reflection, the process offers a rich opportunity to reflect on issues while providing a space to learn from each other and envision action that will enhance their practice and improve their organization. In this case, both teachers and administrators were united in their goal of increasing student achievement. However, different, and sometimes strong, perspectives emerged both within and between these two groups. Despite their shared value of teamwork and belief that their successful collaboration was key to increasing student achievement, they struggled to reconcile differences. As is common in many systems, power dynamics inhibited dialogue, and many participants did not feel comfortable exploring or challenging assumptions held by others.

It became clear to me that these participants would benefit from a deeper understanding of collaboration and the expanded vocabulary that conflict resolution training provides. I therefore integrated a half-day session on conflict resolution into the program design. The training helped the participants deepen their level of dialogue by shifting their focus from positions to underlying needs and determining whether those needs were being satisfied or frustrated. Clearly, the half-day training format did not give participants sufficient time to practice their skills as the longer conflict resolution training format does. However, the shorter module did offer participants new insight into the dynamics they were experiencing and increased their ability to reframe situations more positively. They also expressed commitment to fully engage with one another moving forward and not be conflict avoidant, as they had in the past. One final result worth noting was that the short module whet participants’ appetite for additional learning, a healthy outcome, particularly for a school.

Organizational Mediation with Leadership Coaching, by Susan Coleman

A regular part of my practice is building common ground with groups and departments that are experiencing conflict. I have done this work in different parts of the world with various clients, including large universities, health care organizations, the United Nations, and high-tech start-ups. Both my client and I frame the work in different ways depending on the situation. It can be called “mediation,” “retreat facilitation,” “leadership coaching,” or just “consulting.” The presenting problem is also defined differently depending on the situation: it can be “the leader,” “those two employees,” or “a nonperforming team.” Regardless of how the situation presents, my focus is systemic. One key theoretical foundation for my work is negotiation theory and concepts, including the Coleman Raider model.

A few years ago, I did one of these interventions in West Africa with a UN group of about ten people with a mutiny on its hands. The presenting issue was a conflict between the group leader, Fatou (I use fictitious names), an African woman from another country, and the local staff headed by the most senior man, Derick. The client who retained me was Fatou’s supervisor, Pierre. Tension was high when I became involved.

One of the first things I do in these situations is map the actors using the ingredients of the negotiation planning analysis. I send out a confidential questionnaire that asks each party in lay terms for information on their positions, needs and interests, chips/chops, worldview, emotions, and best alternative to a negotiated agreement. Based on their answers, I identify the issues that need to be addressed. The negotiation and conflict lens is a very turbocharged way to get clear about what is actually going on in a system and how I might best support the client.

My work in West Africa was conducted over a five-day period with different processes, all designed to support positive shifts in climate and build common ground:

- An opening interactive group session to help people learn more about each other and convey some key conflict resolution concepts (here, I wore my trainer hat)

- Confidential interviews with all staff to further understand their perspectives (mediator hat) and explore how they might more positively influence the group dynamic (coach hat)

- Daily updates and coaching of Pierre so that, as the most senior leader, he could positively influence the situation (coach and organizational consultant hat)

- A midpoint whole group conversation to help everyone track developments (facilitator and mediator hats)

- Coaching sessions of individual parties as needed, especially Fatou (coaching hat)

- “Mediation” sessions between parties as needed (mediator hat)

- A closing whole-group session in which all parties made public commitments about actions they will take to continue to improve the situation (mediator, facilitator hats)

The mix essentially included negotiation training, mediation of the whole group, mediation of especially conflicted pairs, group facilitation, and consulting to and coaching of the system leadership.

As the work on the ground came to a close, the group expressed deep gratitude for the experience. Awareness had been heightened, important apologies made, misunderstandings rectified, and the air cleared. After leaving West Africa, I continued to coach Fatou long distance for a time and stayed connected with Pierre. Four months later, I conducted a check-in with the whole group, with positive results.

The training described in this chapter is a powerful tool to build good grounding for all sorts of more complex, live interventions. It is probably not, in and of itself, enough to work effectively in the way I did in West Africa, but it is a great place to start.

Note

References

Coleman, P. T., and Lim, Y.Y.J. “A Systematic Approach to Evaluating the Effects of Collaborative Negotiation Training on Individuals and Groups.” Negotiation Journal 17 (2001): 363–392.

Coleman, S., and Raider, E. AEIOU: An Assessment of Negotiation and Conflict Communication Behaviors [Professional Development 360 Degree Feedback Tool], 2010. http://cglobal.com/products/aeiou .

Griggs Productions. “Going International, Part Two.” San Francisco: Griggs-Productions, 1983.

Hall, E.T. Beyond Culture . New York: Random House, 1976.

Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related-Values . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1980.

Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind . London: McGraw-Hill, 1991.

Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001.

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Movius, H. The Effectiveness of Negotiation Training. Negotiation Journal 24 (2008): 509–531.

Rackham, N. “The Behavior of Successful Negotiators: Huthwaite Research Group, 1980.” In R. J. Lewicki, J. A. Litterer, D. M. Saunders, and J. W. Minton (eds.), Negotiation Readings, Exercises, and Cases . Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin, 1993.

Raider, E. A Guide to International Negotiation . Brooklyn, NY: Ellen Raider International, 1987.

Raider, E. “Conflict Resolution Training in Schools: Translating Theory into Applied Skills.” In B. B. Bunker and J. Z. Rubin (eds.), Conflict, Cooperation, and Justice: Essays Inspired by the Work of Morton Deutsch . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995.

Situation Management Systems. Positive Negotiation Program (4th ed.). Hanover, MA: Situation Management Systems, 1991.

Ting-Toomey, S. “Managing Intercultural Conflict Effectively.” In L. A. Samovar and R. E. Porter (eds.), Intercultural Communication: A Reader (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1993.

Ting-Toomey, S. Communicating across Cultures . New York: Guilford Press, 1999.

Ting-Toomey, S. “Translating Conflict Face-Negotiation Theory into Practice.” In D. Landis, J. Bennett, and M. Bennett (eds.), Handbook of Intercultural Training (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004.

Ury, W. Getting Past No . New York: Bantam Books, 1993.

Weiss, S. E., and Stripp, W. “Negotiating with Foreign Businesspersons: An Introduction for Americans with Propositions on Six Cultures.” Unpublished manuscript, International Business Department, Graduate School of Business Management, New York University, 1985.

Wurzel, J. (Producer). The Multicultural Workplace . Saint Louis, MO: Phoenix Learning Resources/MTI Films, 1990.

Wurzel, J. (Producer). Cross-Cultural Conference Room . Newton, MA: Intercultural Resource Corporation, 2002.