CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CREATING CONSTRUCTIVE COMMUNICATION THROUGH DIALOGUE

Beth Fisher-Yoshida

Communication is the most important means of interaction between people. It is a critical component of our relationships with others. The quality of our communication is important to our relationships, and this is what creates our social worlds. In destructive conflict situations, the quality of our communication is poor; it destroys our relationships and escalates and spreads conflict, perpetuating this destructive cycle. In order to improve our relationships and change our social worlds from destructive conflict to constructive interactions, we need to transform the nature of the communication we have with others.

This chapter discusses transforming communication to create and sustain peaceful social worlds through better-quality relationships. We will look at the communication we use, specifically the content and process of the communication itself, rather than through communication as a means to an end. The focus is on a dialogic approach to communication, which shifts the direction from unilateral to bilateral and will be addressed at a variety of levels: interpersonal, intergroup, societal, and global. We will look at factors affecting communication, our roles and the dynamics we create, the types of messages being communicated, and the influence of context and culture on our communication. Conflict has an impact on those factors, and these problems will be identified with suggestions for shifting the tone of the communication from destructive conflict to constructive interactions. The chapter concludes with ideas for sustaining the transformed communication necessary in an environment of constructive communication.

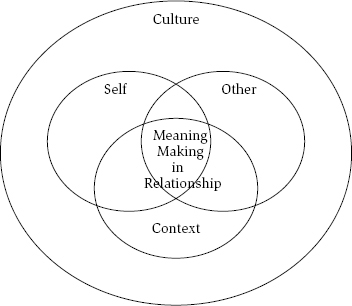

Communication is the process by which we exchange information with others for the purpose of making meaning in our interactions. Making meaning leads to understanding, and as humans we seek to understand because it is a primal instinct that lets us know if we are safe. This understanding derived from making meaning also shapes our subsequent course of action and determines the behaviors we select in response to the other in a particular context. Several elements affect the quality of our communication and influence our meaning making (figure 36.1 ):

Figure 36.1 Elements of Communication Process

- Self and the level of awareness we have about the influences in our lives that shape and frame how we understand the messages of others and how we communicate and interact with others, including the wording, tone, and timing of our messages. It includes how well we know the values we hold and what is important to us. This also reflects on how well we recognize and manage our emotions. Emotions provide information, and the more self-aware we are, the better we are able to channel the energy from our emotions toward constructive outcomes. This is referred to as emotional intelligence.

- Other and how aware we are of what is important to them, how our messages may affect them, and whether this aligns with the intention of our communication. Included here is how we interpret and understand their communication to us to frame it in a way that best aligns with assuming good intentions. There is also connection on an emotional level and more awareness of other means that we are able to use to respond to their expression of emotions in a way that channels their emotional energy toward constructive outcomes. This is referred to as showing empathy.

- Context and the role the environment has in affecting our communication with others. This includes what took place before in the relationship and about the topic, the current climate, and other factors that may be affecting the nature and quality of the communication. Levels of safety, trust, comfort, neutrality, and power shape the space of the context and influence the self in interaction with the other. This has an impact on the quality of the relationship in communication and the ability to coconstruct meaning making.

- Culture , in which all of this is embedded, influences how we create frames that shape how we interpret the world around us. This includes the lessons we have learned about right and wrong, good and bad, appropriate and inappropriate behavior, and how we should lead socially acceptable lives. There are customs and rituals we have embodied, which lead us to have expectations and make assumptions about the other and the way we think things should be.

- Meaning making takes place in relationships and the quality of the relationship that is affected by the interaction of self, other, context, and cultural influences. The more self and other aware we are, the more conducive the context is for constructive interaction, the deeper our understanding of the role of culture, the more receptive we will be to cooperative means of coconstructing meaning in relationship with the other, and the better able we will be to develop the mind-set and skills to do so.

In the next section, we explore the dialogic approach to communication that affects the elements of the communication process and enables us to transform destructive patterns of communication that lead to conflict to constructive patterns of communication that lead to better relationships.

DIALOGIC APPROACH TO COMMUNICATION

Conflict transformation as a process involves changing the nature of the communication between parties in conflict as they engage in dialogue. This in turn alters the nature of their relationships as they find ways to identify common ground through mutual meaning making. Communication is made and transformed in relationship, and relationship is made and transformed in communication. The term dialogue has been used in a number of ways by a number of people, and this naming does not imply shared understanding or process (Pearce and Pearce, 2000). Some of the common themes of the many scholars and practitioners who comment on dialogue and use a form of it in their practice are that it is about deeply listening to each other, joint inquiry in a shared exploration to cocreate understanding, temporary suspension of assumptions, deepening of connection and relationship about our humanity, and a space or container in which all of these can take place (Cissna and Anderson, 1994; Ellinor and Gerard, 1998; Isaacs, 1999; Pearce and Pearce, 2000).

We can think of dialogue as the means to an end or the end in itself (Pearce and Pearce, 2000). Dialogue can focus on the relationship , it can be framed as an event , or it can be thought of as a context . If we think of dialogue as being about relationship, then it is the process through which better-quality communication is made using certain defined criteria, such as moving from hostility, blame, and antagonism to one of listening, respect, and understanding, being fully present, and entering into I-Thou relationships on a mutual level (Buber, 1996).

Buberian dialogue refers to having dialogic communication. In an I-It relationship, the other person is treated as an object, and there is no regard to that person’s humanity, which is more typical in conflict situations. An I-Thou relationship implies a mutual respect for each other’s humanity, and with this comes the attributes of respectful and effective communication. To explore this further, Buber believes it is a shift from the I-It communication to an I-Thou relation, and that dialogue is a primary form of relationship. While much of Buber’s work centers on the interpersonal dynamics of communication between people, he also comments on the broader context and implications of these interpersonal relationships: “True community does not come into being because people have feelings for each other (though that is required, too), but rather on two accounts: all of them have to stand in a living, reciprocal relationship to a single living center, and they have to stand in a living, reciprocal relationship to one another” (Buber, 1996, p. 94).

This is profound in the sense that it reinforces the interdependent relationships we have with each other as social beings. This interdependence can evolve in many ways: where our goals are mutually satisfied, none are met, or a mixed bag with some being met and others not (Deutsch, 1982). Each step along the way influences what will next transpire as we build our relationships through this interdependence. We therefore need to foster a certain quality relationship among us and toward a common, overarching goal that is central to our existence. In the case of shifting from a relationship riddled with destructive conflict, the overarching goal is to create a peaceful existence through better-quality interpersonal relationships that is done through better-quality communication. This happens as we increase our awareness of self, other, and context in the process of making meaning that leads to more constructive communication.

A second form of dialogue, such as that noted by Ellinor and Gerard (1998), refers to having a dialogue: it is a transformational conversation in which a shift in thinking and action takes place. Here it is viewed as an event. People come together with a specific start and end time to hold this dialogue, and this can be a sequence of dialogues to achieve particular goals. These events can be considered rites of passage in which the old form of communication and relationship comes to an end and a new way of communication and relationship begins. There is an implication here that the quality of the communication has the characteristics of what is implied in Buber’s I-Thou relationship, yet the focus is on the event of the interaction as being a dialogue rather than on the relationship. Here is where it is important to recognize the critical role that holding dialogue as an event can have on interrupting patterns of destructive, negative, or otherwise unbeneficial patterns of communication. The dialogue can be a pivotal turning point in breaking these old patterns to experience a different type of communication. There are turning points in the flow of the conversation and the way the parties interact with one another that make a notable difference and create a new pattern toward more mutually beneficial and respectful communication.

Isaacs (1999) refers to a third type of dialogue as techniques used to create the field or space for the co-inquiry to occur. Here we focus on the conditions creating the atmosphere that allows the event of dialogue to take place with the qualities of an I-Thou relationship. In this view of dialogue, participants, facilitators, and organizers identify the qualities needed to change the dynamics to those of openness, trust, and safety with no fear of retribution, so that those involved can feel more inclined to want to change their communication style and tone. This is a significant shift for those in conflict in which the qualities of trust and safety that lead to openness in communication have been eroded. It requires a deliberate, conscious, and skilled effort to rebuild these relationships through improved lines of communication.

In considering the context as a critical factor in dialogue through the involvement of the community and surrounding environment, we are distributing the responsibility across a broader field. If we focus only on the actual communication, the relationship between self and other, there is potentially a great deal of pressure on the involved parties to make a change. These parties grew up in and were developed in their communities, and it was these very social systems or cultures in which they are embedded that influenced and shaped their points of view, how they communicated with others, and the nature of the relationships they had with those within and outside their communities. In addition, there is fluidity between people—the context they are in and the broader cultural system in which they live—so that one influences the other. In order to have more respectful and peaceful communication and better-quality relationships, the environment has to be conducive to fostering these qualities and receptive to this change. Sharing the burden of transforming communication through creating a context receptive to this change must also consider the cultural norms that have guided behaviors thus far and will continue to do so.

These three ways of considering dialogue—as a relationship, an event, or a context—overlap with each other in practice. The importance of noting the differences is that this awareness influences how we think about and prepare for dialogues to take place. Do we want to improve the quality of our communication through increased awareness of self and other for our ongoing relationship as the focus with no specific beginning or end in sight? Do we want to target a specific time frame in which to hold a dialogue as a rite of passage to create a new form of relationship with healthy patterns of communication? Or do we want to focus on the context, social conditions, and cultural norms and values that allow this new form of communication and relationship building to occur?

DIALOGUE PROCESSES

To put this into the realm of practice, I provide some examples of cases in which dialogue as a form of communication was used and discuss the impact this had on the relationships of the involved parties and their communities. They will demonstrate how dialogue can act as an agent to transform the quality of the communication so that parties can transform out-of-conflict communication to that of dialogic communication. In this way, they shift the qualities of their relationships and engage in mutual meaning making, which transforms the meaning they made in their communication when they were in conflict. These examples of different dialogue practices are not meant to represent a comprehensive overview of the field, and they do not claim to be the only or best methods to use. Instead, they can be thought of as good examples of effective practice in the hope that reading about them will foster a better understanding of how they work and why they are effective, so we can apply these approaches to our own work in this area going forward.

Sustained Dialogue

The International Institute for Sustained Dialogue (IISD) was formed in collaboration with the Kettering Foundation. It defines sustained dialogue as “a systematic, open-ended political process to transform relationships over time” (www.sustaineddialogue.org ). The sustained dialogue (SD) approach focuses on transforming relationships through a five-stage process over a period of several meetings. The process has a specifically defined concept of relationship that includes notions about identity, interests, power, perceptions, and patterns of interaction that plays a critical role in organizing and facilitating how a dialogue process will begin and unfold. The five stages are

- Deciding to engage to change their relationships

- Mapping and naming their problems and relationships

- Probing problems and relationships to identify the underlying dynamics

- Scenario building to begin the process of envisioning different relationships

- Acting together to carry out these newly envisioned scenarios and integrate these notions about relationship in their design and process

SD is referred to as a political process, and the IISD is clear in noting that while governments may broker peace agreements, the citizenry holds the power to transform the political climate through human relationships and this is the arena within which they work. Between relationship, event, and context, the focus is on relationship.

Case Study.

In the early 1990s, Tajikistan gained independence from the Soviet Union. The infrastructure in place was weak, and civil war broke out, causing thousands of deaths and resulting in the installation of an authoritarian regime led by former Communist Party members. In early 1993, two Russian members of the Regional Conflicts Task Force (RCTF, which later evolved into SD) approached about one hundred members of the warring factions to see if they would like to participate in a dialogue created by the task force. Over the course of the following ten years, the group held more than thirty-five dialogue sessions, created two of its own nongovernmental organizations for dialogue and democratic collaboration—Inter-Tajik Dialogue (ITD) and Public Committee for Democratic Processes (PCDP), which grew out of the ITD—and participated in UN-run mediated sessions between 1994 and 1997.

In 2000, the PCDP established a multitrack initiative in Tajikistan to rebuild the broken relationships among the people who had previously been embroiled in civil war and to facilitate the post-UN-mediated peace. It did this by establishing regional dialogues so that the people within each community could live in harmony and stability by rebuilding relationships with one another. For the first two years of these dialogue sessions, they focused on creating a shared understanding of the relationship of religion, state, and society in Tajikistan. This was important because the voice of the people was heard, healing was allowed to take place, and they had an opportunity to take an active role in shaping how the government in their communities would be run. In addition, these dialogue sessions led to establishing an undergraduate curriculum in conflict resolution and peace building in collaboration with the Ministry of Education. This educational initiative would instill in young adults the mind-set and skills to resolve issues constructively and avoid another outbreak of destructive civil war. They also developed a procedure for holding public dialogues on issues of national importance to involve the citizenry at large.

The initiative of implementing and developing the use of dialogue as a means of communication to build peace through active involvement of the citizenry worked well here. There were leaders in place who had the energy and skills to recognize the importance of this initiative and a population looking for a way to heal and rebuild community. They knew they would continue to live and work together in interdependence and were determined to create relationships that would allow peaceful coexistence. The focus of SD in this case was on building relationship.

World Café

The World Café developed by chance when a group of business and academic leaders who were gathered for a large circle dialogue in a town in northern California were rained out and instead engaged in smaller group dialogues. They randomly and periodically rotated members of each small group to share and build on insights with the other groups. At the end of that morning, they realized they had developed a new method for gathering collective intelligence that fostered more creative and critical strategic thinking. They wanted to capture what it was that enabled this to take place and through action research in several countries developed the seven design principles of the World Café and the foundational concepts of what they refer to as “conversational leadership” (www.theworldcafe.com/principles.html ):

- Set the context so the purpose for bringing the participants together at this time is clear

- Create hospitable space so the participants feel comfortable and safe to openly share their ideas

- Explore questions that matter to the participants so they feel the relevance of this dialogue to their own lives

- Encourage everyone’s contribution and in doing so acknowledge that people may choose to participate in different ways at different points in the process

- Connect diverse perspectives by having people rotate to different tables and connect the distinct conversations

- Listen together for insights, patterns, and themes that emerge, as the success of the World Café is determined by the quality of the listening that participants do

- Share collective discoveries that is done at the end in the “harvest” portion of the process when the individual table conversations are connected to the whole by identifying common themes and patterns

The World Café design and process is most closely related to being a dialogue event rather than focusing on relationships or context.

Case Study.

There are many examples of the ways in which World Café has made a difference in communities, organizations, and the everyday lives of the participants. Even a few examples demonstrate the breadth of applications for this dialogic event:

- Many people believe that climate change is a growing concern, and they believe people who can do something about it are not paying enough attention to the topic. A World Café was held in Boston, Massachusetts, with its main purpose to strategically develop ways to foreground the conversation on climate change to engage politicians and the public at large to the conversation.

- In the United Kingdom, a World Café entitled “Transforming Conflict” focused on creating innovative ways in which to introduce and develop life skills for children through education.

- In Thailand, over three thousand citizens gathered in conversation about the country’s future. Their recommendations were sent to the future political leaders, an especially poignant outcome considering the escalating conflict of political factions in Bangkok.

- In Mexico, the National Fund for Social Enterprise gathered a diverse group of stakeholders to discuss the focus of the social economy in Mexico and the rest of the world. Decisions were made for the next year’s agenda, and a follow-up World Café was scheduled to build on the year’s initiatives.

By joining diverse voices together to collectively address issues that pertain to them all through a World Café event, more voices are heard and acknowledged and the chances for these recommendations to be implemented and followed are increased. When stakeholders are invited to give voice to their concerns, they have a vested interest in making their recommendations successful. This can be directly linked to more cohesive and peaceful communities.

Public Conversations Project

The Public Conversations Project (PCP) is an organization whose mission is to support individuals, organizations, and communities to be able to have difficult conversations in a respectful and civilized manner. They do this through the use of dialogue, which they define as “a structured conversation or series of conversations, intended to create, deepen and build human relationships and understanding” (www.publicconversations.org/dialogue ). In their work with individuals and communities, they train and facilitate members to use qualities of dialogic communication in their conversations. This includes such characteristics of dialogue as listening so that all are mutually heard, speaking respectfully so that all are understood the way they want to be understood, and broadening perspectives to include those of others in addition to one’s own views. PCP focuses mostly on context aspects of dialogue, knowing that the quality of the communication in relationships needs to be paid attention to as well.

Case Study.

PCP works globally. One example of the work it has done to repair war-torn communities and transform the communication and relationships was in Burundi, where it worked with Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa villagers after their violent civil war. PCP worked with a local organization, Community Leadership Center (CLC), to train a cadre of master trainers to design and facilitate dialogues across Burundi. The master trainers, with the guidance of PCP, learned these skills, carried out pilot dialogues with PCP support, and then took the PCP dialogue principles and practices and localized them to their own culture. In its brochure describing the dialogue process it followed, there were a couple of points worth noting (described in the following), especially in the way PCP and CLC prepared the context for the dialogues to occur (www.publicconversations.org/dialogue/international/burundi ).

Relationships and trust were so destroyed during the years of violence that bringing people together in the same space to engage in respectful communication was an immense challenge. The first step of the process was for the participants and facilitators to create communication agreements, in effect ground rules for the dialogue. This important step makes explicit what will and will not be accepted as a practice in their dialogues as a beginning for establishing a safe environment that will support the participants in rebuilding their trust. The next step was that the facilitators began the dialogue by asking opening questions. Here the facilitators play a key role by getting the conversation started and setting the tone by modeling the types of questions and the manner in which they could be asked. Once the conversation began, participants were encouraged to ask their own questions that focused on curiosity and interest. This focused them on the potential sharing and learning that can take place and not having the conversation turn into a blaming exercise. In closing, the facilitators asked questions to bring the session to an end with the agreement on next steps, which could include more dialogue sessions. The way this process unfolded and the role of the facilitator in action weighed this more heavily on creating the conditions for dialogue to take place, locating it more centrally in the context of dialogue.

The communities in Burundi knew that in order to continue living and building a good quality of life, they needed to shift the dynamics that existed among them. Their once thriving communities had deteriorated into bloodshed, and they needed to do something to regain the safety in their environment and rebuild their community. They elected to learn and practice dialogue as a means to this goal and to localize it so that it was culturally relevant to them.

Other Uses of Dialogue

The three examples present some level of detail of how sustainable dialogue, World Café, and Public Conversations Project used dialogue as relationship, event, and context. Dialogue can have a broader use depending on the purpose and how it is framed. It thus may deepen understanding of the concept and practice of dialogue and appeal to some readers for their own specific purposes. In addition, knowing about them may trigger other ideas as well.

Stewart, Zediker, and Black (2004), in their review of dialogue, identified five core philosophies of dialogue. In these five approaches to dialogue, one particular characteristic stood out as being common to all five, and that was the concept of holism: “For Bohm the ‘implicate order’, for Buber the wholeness of human being, for Bakhtin the whole of speech communicating, for Freire the whole of critical consciousness, and for Gadamer the whole of the relation between the human and his or her world” (p. 26). We can think of this sense of holism as the whole person being engaged, the whole relationship as the focus, the whole interaction and the whole community. In the elements of a communication model, this holism is represented by the integration of self, other, context, and relationship in meaning making, all of which are embedded in the cultural norms and practices that went before and continue. These elements influence the quality of the communication, and altering one element has an effect on all of the other components, as it operates as a dynamic and interactive system.

Yankelovich (1999) indicates that dialogue can be used on a larger scale to bring about social change. Cissna and Anderson (1994) believe that the ideals of dialogue are difficult to sustain as the standard of communication, but that within any communication, there can be dialogic moments. Dialogue requires a high level of awareness of our assumptions, our style of communication and how we express ourselves, deeper listening skills, and that this increased intensity and focus is challenging to maintain over any extended period of time. Pearce and Pearce (2000) build on Cissna and Anderson’s notion of dialogic moments to find a longer stretch of time than a dialogic moment although shorter than a constant norm of communication. They name this an “episode,” which is a series of turns in communication in a given interaction with an agreed-to beginning and end (Pearce and Pearce, 2000). In framing communication in episodes, they view the qualities of dialogic communication as sustained within an episode, which can vary depending on the agreed-to number of turns in the conversation.

Bohm (1997) talks about dialogue as being about collectively changing thought processes and creating the space for that to occur. The collective change of thought processes can be linked to Yankelovich’s support of dialogue as a means toward social change. Bohm’s suggestion about creating the space for dialogue to occur connects the use of dialogue as providing the context for within which it can occur, similar to how the Public Conversations Project case used dialogue.

PROBLEMS IN COMMUNICATION DURING CONFLICT

If we look at the factors affecting communication and assume the worst-case scenarios when these dynamics are in play, we have communication while in conflict. It starts with our not having a developed sense of self-awareness so that we do not fully understand why the actions of others affect us the way they do. This is in large part because we may not be clear about our underlying needs and interests and may be looking for satisfying our surface demands instead. In addition, this undeveloped self-awareness may lead us to not fully understand the impact our actions have on others. It then continues on to our not having a developed sense of awareness of the other party and not holding a shared understanding of what it means to be in relationship with others in the way they envision it. If the context within which these interactions take place is hostile, it can exacerbate the impact of our communication so that the negative attributes of sides are magnified. This creates, fosters, and supports a culture of destructive conflict. Add to this the eroded trust from these destructive dynamics, and we have a strong case for assuming bad intentions as a filter for interpreting and understanding others’ behavior. We will explore the impact of emotions, patterns, framing, and blaming that occur and hamper our communication when we are in conflict.

Emotions

Conflict brings up many emotions, usually negative, and this emotional overlay clouds our thinking, adding to the lack of clarity in our communication and exacerbating the effect of assuming bad intentions. The context may play a role in fueling the conflict if the parties are embedded in a hostile environment that puts them more on the defensive and makes them less willing to engage in open and constructive communication. This makes it easier for the hostilities and conflict to escalate and increasingly more difficult to de-escalate and resolve. The less aware we are of self and other, the easier it is for these dynamics to exist and escalate to control our communication.

Patterns

Our communication style generally becomes habitual and is characterized by specific patterns we use that we may not be aware of. Patterns we default to that do not improve our communication, and in fact may lead to destructive outcomes, may be referred to as unwanted repetitive patterns (URPs). Typically we have reactions that are out of habit and we are not aware of these patterns, resorting to them by default. We may end up in a repetitive rut and wonder why we are not achieving the results we want. If we were aware of these repetitive patterns, the next step would be to want to change them and do something different that is not part of our habit. We may not have alternative methods to use and so may fall back to our default pattern of reacting, knowing full well that even as we are speaking, the communication will not lead to the results we want because it never did in the past. This can lead to frustration and feelings of being stuck in a vicious cycle.

Framing

Our worldview created by our experiences, values, culture, and other influencing factors shapes how we see the world. This way of framing our experiences affects what we pay attention to, how we interpret it, how we understand and make meaning out of it, and how we connect it to what we know and what we believe is important. If we assume bad intentions, as in a relationship in conflict, we will more likely than not frame other people’s comments and actions in a negative light. In addition, we may be prone to interpret their communication and action as having ulterior motives, especially because we probably have a very low level of trust, if any.

Blaming

In destructive conflict situations, we tend to attribute all actions from others as intentionally harmful. If they insist it was not intentional, we will still probably attribute blame to them and fault them for not being more careful, not taking our wants into consideration, and wanting to take revenge against us. Even if we do the same actions to others, we will not attribute the same level of blame to our own behavior because we justify our own actions, even though the other party most likely will attribute blame to us.

* * *

These attitudes and behaviors lead to styles of communication that destroy relationships and are typical of what happens in destructive conflict. In this next section, I offer recommendations on how to improve relationships by shifting our attitudes and behaviors to practice more dialogic communication.

PREVENTING AND OVERCOMING PROBLEMS IN COMMUNICATION

At the beginning of the chapter, I mentioned that we would be looking at communication rather than through it, so that we could focus on the method and process of the communication itself. We explored the basic elements of the communication process and what is needed in self, other, context, culture, and meaning making in relationships to shift from destructive patterns of communication to constructive patterns of better relationships. We reviewed dialogue as an approach to communication that leads to more effective outcomes and improved relationships. In exploring dialogue, we saw that there are three broad categories of how dialogue is framed and approached, including focusing on the relationship, event, or context, yet in practice, the reality is that it tends to be a blended method. We also noted the broader applications of dialogic communication and some of the effects it may inspire. We explored factors affecting communication and how these factors may erode our communication when in conflict situations.

In order to communicate more effectively and subsequently improve our relationships through coconstructing meaning making with our conversation partner, it is necessary for us to pay more attention to the quality and process of our communication. We need to be more deliberate about what we say and how we say it instead of relying on our default mode, which may lead us into URPs. At the risk of becoming hypersensitive, we need to be more thoughtful in how we phrase what we say, in our word choices, in our timing, in the tone we use, and in anticipating the impact on the other party in conversation with us, the surrounding environment and context, and what we hope to achieve as a follow-up to that exchange.

The characteristics of dialogic communication common across many approaches to dialogue are that it involves listening deeply to each other, cocreating shared understanding through joint inquiry, becoming aware of and suspending assumptions, deepening the connection and strengthening the relationship, and taking place in a space or container that allows this to happen so that we get in touch with the essence of our humanity. The following framing addresses these factors in three stages—preparation, in the moment, and reflection—incorporating the themes listed in factors affecting communication (self, other, relationships, emotions, context, and episode) and problems in communication during conflict (emotions, patterns, framing and blaming) so that we can practice and integrate specific practices into our everyday communication. All of the basic elements of the communication process model are addressed in these three stages. If we practice this type of dialogic communication, there are increased chances we will prevent some conflicts from occurring, lessen the possibility that conflicts that do occur will escalate, and that we will be able to resolve our conflicts sooner with solutions that are mutually beneficial.

Stage 1: Preparation

There is some preparatory work that we can do to help ourselves become more self-aware and knowledgeable about those with whom we interact. We have experienced so much in life that there are many layers of influencing factors that have shaped who we have become and are becoming. There are endless opportunities for us to know ourselves and other people more deeply through every experience we have.

Self.

Developing stronger self-awareness is a foundational necessity to improving the quality of communication so that conflict is either prevented or managed constructively. Knowing our worldview, values, and what is important to us helps us identify our core needs and interests and how far we are willing to go to stand up for what we believe in and not feel compromised. At the same time, it helps us prioritize our interests so that we have more clarity when we enter into negotiations with others. There are two suggestions for tools that facilitate this exploration into deeper self-awareness. One is the daisy model from coordinated management of meaning (CMM), which provides a format for us to map our social worlds and the influencing factors that have shaped our worldviews (Pearce, Sostrin, and Pearce, 2011). In the center of the daisy model we put our name and then on each petal surrounding the center, we write in key people, events, and circumstances that have had a profound influence on us. The petals on the surface have a stronger influence at this time, and the petals underneath have a secondary influence. The influencing factors on these petals may change places to be more or less influential depending on the context and relationships with those with whom we are interacting.

A second model is the social identity map that is a Venn diagram, including life context, life choices, and personality attributes (Fisher-Yoshida and Geller, 2009). In the life context circle, we include items such as our cultural background, family status and birth order, socioeconomic status, age, and physical attributes. In the life choices circle, we include educational attainment, career choices, religious practices, and leisure pursuits. In the third circle, personality attributes, are items such as aptitudes, strengths, limitations, and motivations. This information may seem obvious, but we have found that the process of thinking about it, writing it down, and mapping it out brings new insights to people about their core values and the reasons they place importance on certain aspects of their lives. This influences our behavior and the choices we make. The more we understand this, the better able we are to make choices that satisfy our core interests.

Other.

The second part of preparation for dialogue and transforming communication, in addition to knowing ourselves, is to know others with whom we are in relationships. We can use the daisy model and social identity mapping as tools to identify influences on the other party and his or her values, beliefs, and assumptions. We can do this before meeting with this person and then spend time with him or her verifying that what we assumed to be true is accurate or not. This can be done directly by sharing the daisy models and social identity mappings or creating them together if the relationship and context are conducive to this level of disclosure. If not, then we can use active listening skills so that we are attuned to listening for information that can help clarify and verify whether the assumptions we made about the other party are accurate or need to be modified. Either way, knowing more about the other party’s values and beliefs will support us in understanding the other person better and identifying resolutions that will appeal to his or her needs and interests. Using inquiry to gather information and reflecting back what we heard can assure the other party that we hear him or her and acknowledge this person’s interests. In order to do this well, we may first need to create the context that allows safety and trust to be built in order to expand the level of disclosure possible.

Cultural Framing.

The influences that develop who we are and how we see the world create frames from which we view, interpret, understand, and make meaning of our worlds. The more we develop our self-awareness and awareness of others, the more apparent these frames are to us and the more aware we can be about the perspectives we are taking and how these may be biasing our understanding of a situation. This in turn will also influence the decisions we make and the actions we take, and the same is true for our conversation partner. Transforming communication so that we transform conflict into constructive relationships requires us to broaden our perspectives so that we can see, interpret, understand, and make meaning from more than one perspective (Fisher-Yoshida, 2009). Using different frames offers us a broader spectrum of possibilities, which can allow us to be more creative in seeking mutually beneficial outcomes to a conflict situation.

Stage 2: In the Moment

Engaging in dialogue with others requires good listening skills to create shared understanding that is mutually beneficial. We are able to do this more effectively once we have a stronger sense of self-awareness and awareness of others because we will have been able to identify our core needs and interests through this exploration. The more developed this awareness is, the better equipped we will be to engage more deeply in empathic listening and clarify our own thoughts and feelings. It might be helpful to frame dialogic encounters as episodes (Pearce and Pearce, 2000) so we can clearly mark the beginning and end of a series of conversation turns within an interaction. This framing of a dialogue as an episode would lend itself to all three approaches to dialogue as building relationship, holding an event, and creating the context. This section addresses the dialogic episode by looking at relationship, context, and dialogic communication.

Relationship.

Dialogic communication builds relationship because within these dialogic episodes, we are engaging in quality communication that improves our mutual understanding. There is an increased chance of feeling heard and acknowledged, and this empathy can go a long way in improving relationship dynamics. In addition, through relationship building, we are able to address dynamics that may stem from power differences to level the playing field within these episodes. These dialogic episodes transform the very nature of our disjointed and destructive communication in conflict to one of mutual benefit and caring as we engage in meaning making in peace.

Context.

We need to create suitable conditions that make it easier for us to be open and receptive to listen to others more deeply and express ourselves in ways we want to be heard (Isaacs, 1999). This space needs to make us feel safe and to have trust in the process and others, which is a leap of faith when we have been in conflict. Having a facilitator (as mentioned in the Public Conversations Project work in Burundi) often provides the security for feeling safe and developing trust as the participants initially rely on the facilitator to be the protector and enforcer of the agreed-on ground rules. This responsibility will eventually be shared by all once their experiences in these dialogic episodes strengthen their relationships and trust.

Dialogic Communication.

The characteristics of dialogue communication include empathic listening in that our focus is on listening to understand. Gathering information through good listening skills helps us identify the core needs, interests, and feelings of the other party with whom we are in communication. Listening as a first step is a way to show caring and can then relax the other party and open him or her up to being more receptive to hearing what we have to say. There is a craft and an art to expressing ourselves constructively. The craft is to phrase our thoughts and feelings in ways that are easier for the other party to hear and accurately reflect what we want to say. The art involves developing sensitivity to timing, framing, pacing, and phrasing that is favorable to a constructive conversation and relationship building.

We all make assumptions, which can be traced back to tactics we use for survival. In dialogue, it is important to temporarily suspend the assumptions we make or look for confirmation to prove them accurate or not. This deepens the connection we make with the other party, which shifts the tone of our interaction and improves the quality of the relationship. Stringing a series of these dialogic episodes together can dramatically transform the nature of the relationship. New habits and patterns are being formed to replace the URPs that may have characterized the relationship and conflict in the past. There is mutual respect even in disagreement and a desire to honor and stay with the process because of the belief that it will lead to beneficial outcomes.

Stage 3: Reflection

There is much learning opportunity in the space we set aside for reflecting on our interactions and communication. Argyris and Schön (1974) identify reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action as two stages of reflective practice. When we engage in reflect-on-action, it is after a communication is completed, and we look back over what took place, assess the process and outcomes, and examine the status of the relationships as a result of that interaction. When we do this on a regular basis, we build up experience on reflecting and being able to identify best practices that we can then apply to future communication. Reflecting-in-action takes place when we can take a metaview of the situation and detach emotionally from what is happening so that we can look at it with an eye toward assessing the process and whether it is leading us toward desired outcomes. The advantage of reflecting-in-action is that we are better able to redirect our communication in the moment, as it is taking place, and ensure more constructive outcomes. Dialogic communication is what reflective learning can foster. It is a method that needs practice in order for it to become more deeply ingrained in how we operate on a regular basis. This section addresses reflective processes from the perspective of critical reflection and unwanted repetitive patterns.

Critical Reflection.

This can take place whether we are reflecting on action or in action as long as we are identifying our assumptions, beliefs, and perspectives. The act of critically reflecting stimulates us to become more conscious about what we think and feel and how that relates to the decisions we make and the actions we take. This process is a disciplined way to surface hidden assumptions we have about ourselves, other people, our situation, and the context and how this influences the perspective we take (Mezirow, 2000).

One of our challenges is that when we are in the middle of an interaction and if it is a conflict situation, our emotions may cloud our judgment, and we will not be able to engage in reflection-in-action. In reflection-on-action after the interaction has concluded, and our emotions are back to normal, we can have a less biased and emotional view of the situation and may be able to gain insight into the interaction. Another model that might be useful in these situations to use individually or with others is the quadrants-of-reflection chart with guiding questions (Fisher-Yoshida and Geller, 2009). One axis represents the individual and group and the other in-action and on-action. A series of questions within each quadrant can be used to stimulate dialogue and reflection on the process of interaction. This is especially useful as a tool to use in teams to reflect on group process.

Unwanted Repetitive Patterns.

In addition to reflecting on our assumptions, beliefs, and perspectives, we can reflect on the patterns of our communication and whether any URPs are inhibiting us from having more productive communication. These URPs can be interrupted through this focus of consciousness by looking at our communication rather than through it. First, we need to recognize that our communication has fallen into a pattern of responses that is not benefiting us and may be causing our relationships to deteriorate. We then want to identify ways in which we can interrupt these patterns to change the dynamics for better outcomes.

The more we have developed our self-awareness, the more we will know our core needs and interests. A model that may be useful to detecting URPs is the serpentine model in CMM (Pearce, 2007). This model helps to track the flow of the conversation, and within this flow, the parties take turns in the communication. Each one of these turns can be thought of as a bifurcation point or critical moment (Pearce, 2007). Bifurcation points are choice points we have within any communication episode. Someone says something to us as a first turn in a conversation, and we have a choice as to how to respond in the second turn. How we respond will influence the next choice or third turn our conversation partner makes, and so on. Each response stimulates a response from the other person. Being more deliberate about the choices we make will help direct the communication flow toward a more constructive and desirable outcome, creating new and healthier patterns of communication.

CREATING NEW SOCIAL WORLDS MADE FROM DIALOGIC COMMUNICATION

This chapter has focused on looking at ways to transform communication so that we shift from conflict communication to dialogic communication. This shift changes the quality of our communication, interactions, and relationships, resulting in better social worlds. Why is this important for sustaining a more constructive environment?

If we think about the communication patterns we create and sustain out of habit, we can use this to our advantage by creating and sustaining healthier patterns of communication, which build healthier relationships. Earlier in the chapter we identified dialogic episodes as being more sustainable than ongoing dialogic communication and more expansive and extensive than dialogic moments. Making these dialogic episodes more of a reality, even if only an intention as a beginning, will support the creation of a different type of interaction from what may have been experienced in the past. It is certainly different from what happens between people in conflict.

Conflict is habitual, and it engages us in URPs that lead us to destructive relationships and deteriorating social worlds. When we have experienced that over a period of time, it becomes tiresome and an energy drain. Turning these patterns upside down so that we create constructive habits and patterns is not only possible but desirable. They will be easier to sustain in small bites. The more we practice and support these dialogic episodes, the more they become a part of who we are, a part of our communities, and the new social worlds we are creating.

References

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bohm, D. (1997). On dialogue . New York: Routledge.

Buber, M. (1996). I and thou . (W. Kaufmann, Trans.). New York: Touchstone Book. (Originally published in 1970.)

Cissna, K. N., & Anderson, R. (1994). Communication and the ground of dialogue. In R. Anderson, K. N. Cissna, & R. C. Arnett (Eds.), The reach of dialogue: Confirmation, voice, and community . Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Deutsch, M. (1982). Interdependence and psychological orientation. In V. Derlega & J. L. Grzelak (Eds.), Cooperation and helping behavior: Theories and research . Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Ellinor, L., & Gerard, G. (1998). Dialogue: Rediscover the transforming power of conversation . New York: Wiley.

Fisher-Yoshida, B. (2009). Coaching to transform perspective. In J. Mezirow & E. W. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fisher-Yoshida, B., & Geller, K. D. (2009). Transnational leadership development: Preparing the next generation for the borderless business world . New York: Amacom.

Isaacs, W. (1999). Dialogue and the art of thinking together . New York: Currency.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformation theory. In J. Mezirow & Associates (Eds.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pearce, W. B. (2007). Making social worlds: A communication perspective . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Pearce, K. A., & Pearce, W. B. (2000). Extending the theory of the coordinated management of meaning (CMM) through a community dialogue process. Communication Theory, 10 , 405–423.

Pearce, W. B., Sostrin, J., & Pearce, K. (2011). CMM solutions: Field guide for consultants . Tucson, AZ: You Get What You Make Publishing.

Stewart, J., Zediker, K. E., & Black, L. (2004). Relationships among philosophies of dialogue. In K. Anderson, L. A. Baxter, & K. Cissna (Eds.), Dialogue: Theorizing difference in communication studies . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Yankelovich, D. (1999). The magic of dialogue: Transforming conflict into cooperation . New York: Simon & Shuster.