CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

MANAGING CONFLICT THROUGH LARGE GROUP METHODS

Barbara Benedict Bunker

Susan W. Coleman

This chapter begins in practice and works backward toward the theoretical question: Are there situations where managing conflict is enough, that is, in which our socialized desire for conflict resolution may be more than is really needed for joint action?

We live in a world in which our environment is continuously changing. Organizations and communities are constantly dealing with new developments and pressures. A predictable and stable world surrounding organizations and communities is a luxury we used to take for granted and no longer exists. In the United States, we are also living in communities and in organizations at work in which our diversity and our awareness of our differences in values, ethnicity, and religion are increasing. Learning to manage these differences is becoming ever more important. This new situation requires organizations that are far more flexible and responsive than those in our past. It requires communities to develop ways of gathering people for input and planning immediately, not six months hence. It requires methods that can acknowledge and deal with differences, not suppress them in the service of homogeneity.

Practitioners of organization development (OD) who consult with organizations and communities have developed large group methods of working with the whole system in large groups. These remarkable methods allow groups ranging in size from fifty to several thousand to gather and work together. Barbara Bunker and Billie Alban have been studying these methods since the early 1990s. Their book, Large Group Interventions: Engaging the Whole System for Rapid Change (1997), is a conceptual overview of twelve major methods, what underlies their effectiveness, and how they work. They edited a special issue of the Journal of Applied Behavioral Science in 2005 that presented new trends and developments in the use of these methods. Their Handbook of Large Group Methods (2006) updates their first text and presents detailed cases that demonstrate the contemporary reach and use of these methods.

In this chapter, the first three sections are an overview of the three types of methods now in use: methods for creating the future, methods of work design, and methods for discussion and decision making. In each section, we describe the methods and then speculate about the processes that allow conflict to be managed and sometimes resolved in these events. Then we turn to the recent innovations of Coleman and others using these methods in peace-building and legislative processes. Finally, we review the underlying principles that make these methods effective in dealing with differences.

WHAT ARE LARGE GROUP INTERVENTION METHODS?

These methods are used to create systemic change such as a new strategic direction for a business, the redesign of work in order to be more productive, or the resolution of some community- or systemwide problem. In contrast to older methods where decisions were made by an executive group at the top of the business or in the mayor’s office, these methods gather those who are affected by the decision or actions to participate in the discussion and decision making. In business organizations, this might include employees, customers, suppliers, even competitors. In school districts, teachers, administrators, and board members might be joined by students, parents, and community representatives. In communities, agencies, schools, churches, police, housing areas, and local and state government might all be present. Depending on the nature of the issue, the question is asked: “Who is affected by this decision or action? Who has a stake in the outcome?” The idea is to get the whole system into the room with all of the stakeholders so that a new kind of dialogue about the situation they face can take place. The size of the group assembled is determined by the critical mass of people needed to bring about real change and is constrained by limitations of budget and available meeting space.

Why bring together so many people? Why not let the decision makers do their jobs and make the decisions? This question leads us to the second major defining assumption of large group methods. The assumption is that when people have an opportunity to participate in shaping their future, they are more likely to sustain the change; in other words, people support what they help to create. These are very participative events: people express their views, listen to others, have voice, and are heard. They do not necessarily make every decision, but they have the opportunity to influence others and the decisions.

Stakeholders in communities and organizations bring knowledge, values, and experience to these events. Many of the decisions that face us today are enormously complex and need the best thinking and experience of all those involved, not just a few. Executives who participate in large group events for the first time are often moved by the amazing variety of talent and capacity in their organizations. They often make remarks like, “I had no idea how great and how talented the people in this organization are! It has been a revelation to me!”

Underlying these methods is an assumption that democratic processes are more effective for moving forward in a united direction than hierarchical or bureaucratic processes. This assumption closely matches Deutsch’s ideas about the values underlying collaboration and cooperation. (See chapter 1.)

THREE TYPES OF LARGE GROUP METHODS

A useful way to organize these methods is by the outcomes that they produce. A brief description of each type with an anecdote that illustrates one of the methods follows.

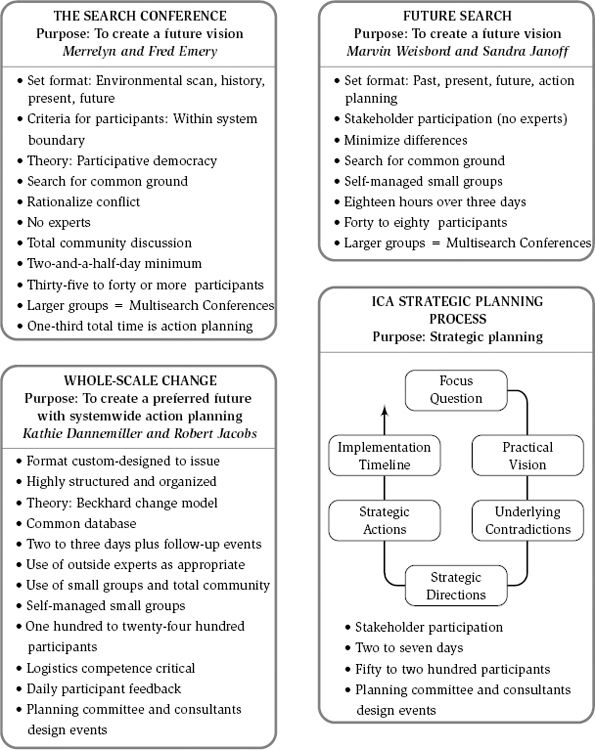

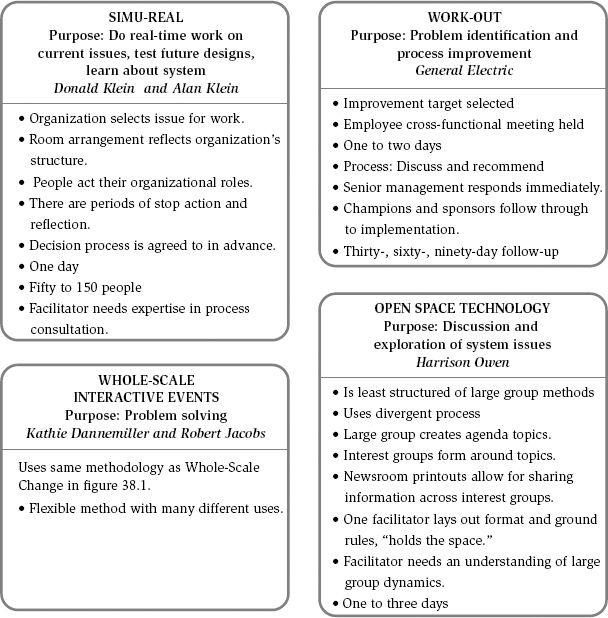

Methods That Create the Future

Future Search (Weisbord and Janoff, 1995), the Appreciative Inquiry Summit (Ludema, Whitney, Mohr, and Griffin, 2003), the Search Conference (Emery and Purser, 1996), the Institute of Cultural Affairs Strategic Planning Process (Spencer, 1989), Real Time Strategic Change (also called Whole-Scale Change) (Jacobs, 1994; Dannemiller Tyson Associates, 2000), and AmericaSpeaks (Lukensmeyer and Brigham, 2005) are six methods that gather systems to define and set goals for the future. (See figure 38.1 for summaries.)

Figure 38.1 Large-Group Methods for Creating the Future

Source: Adapted from B. B. Bunker and B. T. Alban, The Handbook of Large Group Methods: Creating Systematic Change in Organizations and Communities . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006. Reprinted by permission.

“What kind of school system do we want to be by 2015?” “What new market niche can we create in the next three years?” “How can we be a community with housing for all by 2020?” “How can agencies and funders collaborate to provide better mental health service delivery?” All of these are appropriate theme questions for these future-oriented conferences.

Each future-oriented event is carefully planned by a group representing the sponsoring system working with a consultant who is expert in the method. For example, the planning committee for a Future Search for a small Jesuit college business school about what it needed to do with its curriculum to create a successful future for the MBA program included representatives from the dean’s office, faculty, staff, students, alumni, and the business community. A planning committee of all the stakeholders creates a better understanding of the whole system and helps anticipate conflicts that may emerge in the large group meeting. Sometimes these conflicts can even be resolved in the committee so that they do not emerge on the floor of the large group. It also builds trust in the process as all sides are represented.

To show what the meetings are like, here is a description of a Future Search that occurred in Danbury, Connecticut. The initiating concern that brought the community together was the rapid increase in violence in schools as well as in the community as a whole. Realizing that “reducing violence” was too limited an emphasis for the future they wanted, they finally agreed on “creating a community free from fear” as the theme.

Imagine 180 people arriving at a big hall and picking up name badges that assign them to one of twenty-three five-foot round tables that seat eight. They are purposely assigned as heterogeneously as possible. This means that they will meet and work with representatives of all the other stakeholder groups at their assigned tables. Each table is designed to be a microcosm of the system in the room.

Future Search begins with a statement of purpose from the sponsors, and then everyone is asked to participate at their tables in an activity that reviews the history of the community, the world, and each person over the past thirty years. Using a worksheet, people think about the important events in these histories first. Then everyone gets up and writes their important events on long sheets of butcher paper that have been posted on the walls and labeled by decade. After everyone has put up their thoughts, the facilitators assign each table to do an analysis of the patterns they see and report their analysis to the whole assembly. This activity gets people involved and working together at the tables. In the course of the analysis, the history of the system is shared with everyone, the impact of the environment on the system is better understood, and people get to know each other personally.

Creators of Future Search have developed a “design,” or series of activities: discussion, self-disclosure, imagining, analyzing, and planning. These activities have both an educational and an emotional impact on participants. They represent the major steps in any open systems planning process (Kleiner, 1986). Thus, there are activities that scan the external environment and notice the forces affecting the organization or community. Next, there are activities that look at the capacity of the organization to rise to the challenges it faces. Then there are activities that ask people to dream about their preferred future in the face of the reality that they confront. Finally, there is work to agree on the best ideas for future directions and action planning to begin to make it happen. Although the overall plan is rational, the activities themselves are also emotionally engaging, fun, and challenging. The interactions that occur among people create energy and motivation for change.

In two days, the conference in Danbury discovered in their history that the sense of community had been disrupted by the loss of industry that moved out, the building of a superhighway that bisected the town, and the loss of the well-known community fairgrounds that brought the community together. In addition, new groups were moving into the area. They learned that forty-two languages were now spoken in the high school, creating new educational issues. When they assessed the resources of the community, they found that many groups did not know what other groups were doing and that there were untapped opportunities for synergy, coordination, and cooperation. The skits that groups created developed themes about housing, racism, hospital services in underserved areas of the city, and summer recreation transportation for children. Action planning groups were formed and began work. In two days, 180 people created over a dozen major initiatives to improve life in that community. Two years later, a number of these task forces were still at work and a number of major initiatives had been completed. Three other future methods—Search Conference, ICA Strategic Planning Process, and Whole-Scale Change—all have elements in common with Future Search. They vary in design activities, the structure of decision making, and how many people they can accommodate.

The work of AmericaSpeaks focuses on citizen participation in democracy. In the aftermath of 9/11, there was furious debate about what was going to happen to the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan. Many stakeholders—the people who lived in the area, the site owners, the tenants, the survivors of the disaster, the families of the victims, people from nearby states who worked in Lower Manhattan, the transportation authority, police, firefighters, and more—had divisive and competing ideas about what they wanted to see there. AmericaSpeaks created a one-day meeting in the Javits Convention Center in New York City to which forty-five hundred representative stakeholders came to express their views on how the site should be developed. Using voting keypads and computers to enter their views at the round tables, these were presented to the decision makers at the end of the meeting and changed the architect’s plans for the site. To be sure that the views are a valid representation of all stakeholders, AmericaSpeaks goes to great lengths to ensure that people attend in numbers that represent the prevalence of their stakeholder category. AmericaSpeaks is committed to creating processes that help citizens find their voice and be heard in projects at the national, regional, and city level (Lukensmeyer and Brigham, 2005).

A radically different approach is taken in the Appreciative Inquiry Summit. This method takes only a positive approach to change. In examining history, for example, it looks for the very best experiences from the past in order to carry that best into the future and amplify it. No attention is given to negative experiences that, if they emerge, are required to be translated into future desires. Appreciative Inquiry has been extraordinarily effective in organizational mergers because it provides a process for affirming the best of both organizational cultures rather than the usual takeover by one culture of the other. However, whether it can be effective in deeply divided systems where conflict is rampant remains a question.

Dealing with Differences about the Future.

One would think that when you bring together people from many different interests and perspectives, you are bound to have conflict or at least major differences about perceptions and future directions. What keeps these methods from blowing up? So many aspects of organizational and community life disintegrate into bedlam. Why don’t these events?

First, of course, there are differences—real differences and many of them. But all of these events operate under a different assumption from, say, a traditional town meeting or a hearing in front of the city council. The key here is the search for common ground. People are asked to focus their minds and energy on what is shared. Early activities in all of these events create a shared data base of information as well as personal connection with those present. People are encouraged to notice and take differences seriously, but not to focus on them or give a lot of energy to conflict resolution. Rather, they try to discover what they agree on, and this becomes the base for moving forward. Usually they are surprised by how much agreement there actually is when they look for it. This is because the usual process of focusing on differences has been disrupted. When people are focused on making their points stick, on winning, they tend to lose sight of what they have in common with others and see only the difficult differences.

Some years ago, National Public Radio had a story that illustrates this different approach. It was reported from St. Louis where the pro-life and pro-choice forces were poised for escalating violence. Some leaders in both groups wanted to avoid violence. They asked, “Is there anything that we agree on that could become a source of common ground?” And although there is much that they will never agree about, they discovered common ground in their mutual concern for pregnant teenagers. As a result of this discovery, they created a successful jointly sponsored project to help pregnant adolescents that did a great deal to manage the incipient violence in that city.

Merrelyn Emery’s thinking about the relationship between conflict and common ground in her writing about the Search Conference makes these issues very clear (Emery and Purser, 1996). She sees the conference setting as a “protected site” where people can come together and search for commonalities despite their fear and natural anxiety about conflict. She believes that “groups tend to overestimate the area of conflict and underestimate the amount of common ground that exists” (p. 142). “Rationalizing conflict” is the important process that takes conflict seriously when it arises so that the substantive differences are clarified and everyone understands and respects what they are. A short time is allowed to see if it can be resolved. If not, it is posted on a “disagree list,” meaning that the differences are acknowledged and that the issue will not receive further attention.

At the Seventh American Forestry Conference held in 1996 using the Whole-Scale method, the importance for conflict management of the principles and processes just discussed is further illustrated.

Before the congress was convened, over fifty local roundtables and collaborative meetings were held all over the United States to develop draft visions of forest policy for the next ten years and principles to support them. These meetings included environmental groups, lumbering, public agencies, small business owners, research, and academia. In this prework, it became clear to the conference planning committee that they could not use the traditional talking heads conference format. They chose Kristine Quade and Roland Sullivan, organization consultants from Minneapolis, Minnesota, to design and facilitate the conference.

When the fifteen hundred people invited to the three-and-a-half-day conference convened in Washington, DC, in 1996, the draft visions and principles already created by these local meetings formed the basis of discussions at the tables. The table task was to incorporate the various visions and principles into one set that most people could endorse as the desirable policy for the next decade.

In order to avoid the win-lose confrontations so typical of public issues with diverse stakeholders, they adopted several ground rules:

- The leadership did not take positions on controversial issues even though there were interest groups present that wanted them to do so.

- They used color cards to vote or show where they stood. Green signaled agreement; yellow indicated uncertainty or ambivalence; red meant disagreement. Agreement was declared when more than 50 percent of the congress was green. This method created space to explore people’s views, especially the meaning of a yellow vote.

- Some potentially explosive issues such as divisive pending legislation were avoided as part of the agenda for the congress. In other words, the level of conflict was managed.

On the first day, people worked together at diverse table groups of ten. Then many information sessions by knowledgeable experts were offered. Tables decided where they wanted members to go and these members came back and reported what they had learned to their table team after each of these sessions. During the second and third days, table deliberations were integrated, creating visions and principles that more than 50 percent of those assembled agreed on. Finally, time was devoted to planning next-step initiatives to carry forward the vision and principles.

In the course of discussions, acquiring new information, and trying to move toward agreement, people begin to understand, if not agree, with others in their group. Boundaries become less rigid, and they become more flexible in looking for solutions that might provide gains for both themselves and others on their table team. As they engage in this cooperative process, the atmosphere at the group level becomes supportive and affirming, and the group begins to feel successful. One symptom of this shift in perspective is that rather than saying “I,” there is a noticeable increase in the use of “we.”

Interestingly, at this congress, there was a group of about two hundred delegates who did not like the participative way the congress was organized and met in rump sessions to plan demonstrations and disruptions. As the table groups worked together, however, fewer and fewer of the original dissident delegates were willing to go to rump meetings or participate in disruptive demonstrations. They realized that they could get some of what they cared about through this more collaborative process. Toward the end, only a single person, the leader of this movement, was still walking around the floor picketing and trying to arouse others. The process had clearly captured and engaged all the others.

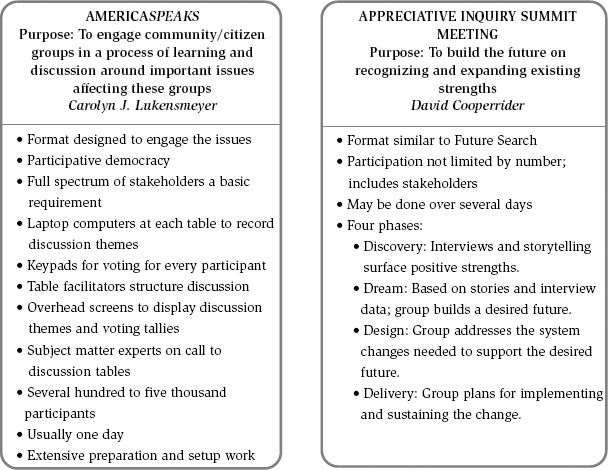

Methods for Work Design

The second group of methods involves stakeholders in the redesign of work. (See figure 38.2 for a summary.) Large group work design focuses on optimizing the fit between efficient technology and a responsive and motivating human environment for workers.

Figure 38.2 Large-Group Methods for Work Design

Source: Adapted from B. B. Bunker and B. T. Alban, The Handbook of Large Group Methods: Creating Systematic Change in Organizations and Communities . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006. Reprinted by permission.

In the Conference Model (Axelrod and Axelrod, 2000), large conference meetings are interspersed with smaller task forces in a pattern that makes sense for each client. This always includes addressing future goals for the organization as both a business and a social system, an assessment of the impact of the environment on the organization, a technical analysis of the core work process, and a redesign of that process and the structure that supports it. This participative process is used in all types of organizations from hospitals to manufacturing plants and usually takes up to six months to complete.

In the Mercy Healthcare system in Sacramento, California, for example, five hospitals needed to redesign their patient care delivery processes, a core hospital process. They needed to save money and at the same time improve patient care. The first conference, the Vision and the Customer Conference, created a vision of the goal of patient care and involved customers (in this case, former patients and the community) in describing their needs. Then there was an analysis of the current patient care process and where it needed to be improved (the Technical Conference) and a Design Conference to make changes to create improved service delivery with the organizational structure to support it. Finally, the decisions were refined and acted on in the Implementation Conference.

The Technical Conference was held in five adjacent ballrooms, one for each hospital, so that there could be coordination among the hospitals. For example, at different moments in the process, selected members of each hospital went on a “treasure hunt” to the other four ballrooms to look for good ideas that they could incorporate from others. These conferences are usually held about a month apart, which gives time for designated teams to go back into the system, present what has happened to those not attending, and get their input for the next conference. When Mercy Healthcare surveyed three thousand people in the hospital system, 85 percent said that they felt involved and able to give input to the process. This is rather remarkable since only about 150 people from each hospital attended any conference.

The underlying principle here again is that there is a great deal of wisdom and experience in the people who do the work and deliver the service. They, better than even top management, often know where the problems are and what goes wrong at work. Therefore, they need to be involved in the analysis and redesign process. Even if jobs are at stake, as they were at Mercy Healthcare, people would ordinarily rather have a voice in what is changing than have it done to them. In situations of cutbacks and change, anxiety runs high. It helps manage anxiety if there is openness and regular communication about the process of change and how decisions will be made.

The other work design method is distinctively different. Participative Design, created by Fred and Merrelyn Emery (1993), is a method that redesigns work and the work organization from the bottom of the organization up (see figure 38.2 ). It is based on the idea that the people who do the work need to be responsible for, control, and coordinate it. This is in sharp contrast with the bureaucratic principle where each level controls the work of those below them. Work is redesigned to conform to the critical human requirements that create meaningful and productive work. Management decides in advance what constraints or minimum critical specifications the unit must work within—for example, that they cannot add jobs or exceed certain budgetary levels. Within these limits, the whole work unit analyzes what skills are needed to get the work of their unit done and who has them. Next, they redesign the unit to meet both the objective criteria for satisfying work and their own requirements. After the bottom of the organization is redesigned, the next-higher level asks, “Given this new work design, what is our work?” and proceeds to redesign it. Theoretically this continues to the very top of the organization. To be successful, Participative Design requires top management to understand and endorse this democratic approach to working with employees.

Interpersonal conflict occurs most often in the Participative Design workshop when people in the work unit are analyzing their work and creating a new organization that they will manage and be responsible for. According to Nancy Cebula, an experienced practitioner doing work with this method, about halfway through the redesign process, the group wakes up to the fact that in the new world that they are creating, they will have to deal with and manage their own conflicts. This is usually a new experience because in hierarchically controlled organizations, people can run to the boss and complain and expect her to do something. Self-managing units, however, must develop processes for dealing with conflicts in their own team and with other teams. For this reason, teams are encouraged to work out a script for the steps they will take when conflict appears. They may start by having the affected parties try to talk it out; then it may become team business. Some teams have rotating roles for mediators. The steps can include calling in human resources to mediate as a last resort. Defining the process in advance helps people openly deal with issues.

In one team on the verge of becoming self-managing, the process faltered when the group seemed unable to select people for the two new teams that were proposed. Someone finally blurted out to the inquiring facilitator, “Our problem is that we have two slackers in the group and no one wants them on their team.” The facilitator asked, “What’s the best way to deal with this?” The group decided to go off into a room and deal with it without their manager or the facilitator. The facilitator said they could take one hour. They retired to the room, from which angry sounds emerged from time to time. Thirty minutes later, however, they emerged with two teams, each including one of the slackers who had been told that they would have to shape up or depart. They had had their first experience at managing their own conflict. Interestingly, one of the slackers quit within a few days. The other turned herself around. She could no longer be mad at the system. Now there were peers in her world to whom she was accountable.

Managing Conflict in the Redesign Process.

Because the people who come to work design events belong to the same organization and have a stake in its future, it is not in anyone’s self-interest to let the organization die. Even if labor relations have been troubled and there are intraorganizational battlefields, there is always a certain level of energy for change and improvement.

Training in conflict management, particularly in systems where there is a strong history of conflict, is often part of the prework that gets a system ready to do participative design.

For some organizations with a long history of mistrust between labor and management, an invitation to participate will not be easily believed. This history is likely to be in evidence in the large group meeting. It appears in a number of forms. Often it is carried by outspoken individuals who make themselves known on the floor. Although the rules of large group events are that people and their views will be listened to and treated with respect, what do facilitators do when someone grabs a microphone and unleashes a tirade against management? On the one hand, these people deserve to be treated with respect. On the other, they are not authorized to speak, and their speech violates acceptable behavior. Often such a person will instigate others with similar axes to grind. In all likelihood, they represent only a small percentage of those present, but their aggressiveness is often intimidating to those whose views are more moderate and are more hesitant to express themselves in front of five hundred other people.

One theory that governs this kind of emotional display is catharsis theory. The idea is that you let dissidents speak their minds, even if it disrupts the time schedule, but you do not let them filibuster or totally disrupt proceedings. If they are not willing to stop after a reasonable time, you may call a short break (everyone else will depart for the coffee and restrooms) and then go on to the next activity.

In one plant in the Midwest with a troubled labor history that Bunker observed, a vocal group of disbelievers in management’s good intentions was holding forth in negative and strong voices. After about fifteen minutes, Bunker wandered out into the hall, where, to her surprise, she found a lot of people grousing. They said things like: “It’s always the same people, and they always say the same things. Why don’t they shut up, and let’s see what happens. I am tired of listening to them.” After the break, when people went back to work on the next activity, the energy level in the room was high and positive. People were deeply engaged and making suggestions for changes that would improve work at the plant.

A second strategy that is sometimes useful is to respectfully engage the whole group in reacting to what is being said by the vocal minority. For example, a facilitator might ask for an indication of those who agree with what is being said and then ask for those with different views to make themselves known. Facilitators often ask questions that bring out other points of view. Moderates need encouragement to express their views, but when they do, a clearer picture of the views of the whole system begins to emerge. As others join the discussion, the community begins to manage it. People will say things to the people hogging the floor like, “Joe, you know you are taking advantage of this and that we don’t support you. Why don’t you sit down and shut up?” Working in this context, the facilitator senses when the group has had enough and is ready to move on to the next steps.

There are times, however, when the frustration and aggravation with the organizational situation and with management is very strong, and for good reason. If people have not been treated well, they need to be able to say this publicly to management and hear the response. This level of conflict has the potential of escalation and of taking a destructive turn. If voices from the floor become personally accusative and cross the invisible line of acceptable public behavior toward superiors, a bad situation could occur. This is everyone’s worst fantasy about large groups—that there might be an irreparable explosion that would do permanent damage.

Although this possibility always exists, it is important to consider and harness the other forces working in this setting to keep conflict within responsible limits. An organization is not an association of persons with no particular bonds. There is a history, a present, and, it is hoped, a future. It is in everyone’s self-interest that things come out better rather than worse. These forces encourage collaboration and help to keep the conflict in bounds. In a large-scale event, conflict is a public process that occurs with the whole system present. The public nature of the conflict is also a force for responsible management of the conflict. The facilitator’s skill to martial the positive forces while at the same time allowing the expression of the conflict is key to its successful management.

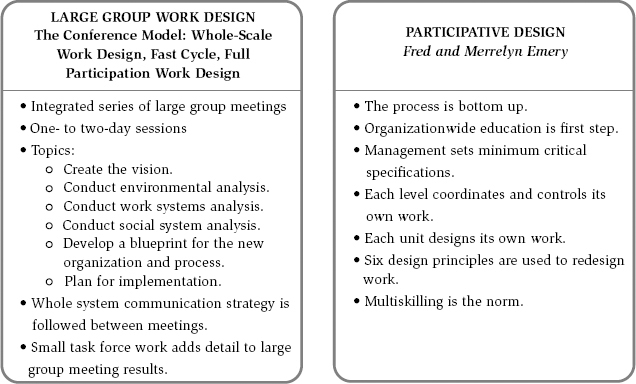

Methods for Discussion and Decision Making

This is the third category of methods developed as ways to diagnose and find solutions to problems, or explore and understand issues.

The large group methods used for these purposes are substantially different from each other (see figure 38.3 ). Work-Out is a method developed at General Electric that is being used in numerous companies to solve serious organizational problems by bringing together all of the stakeholders in a time limited problem-solving format. Simu-Real (Klein, 1992) creates a simulated organization with the real role holders acting their own jobs in order to understand problems or even to test out a new design for a new organizational structure. Large-scale interactive events uses the Whole-Scale Change framework to solve many types of problems from diversity issues to intergroup coordination problems—for example, to get police, emergency rooms, agencies, and homeless shelters to better deal with the rise of tuberculosis among homeless people in New York City.

Figure 38.3 Large-Group Methods for Discussion and Decision Making

Source: B. B. Bunker and B. T. Alban, The Handbook of Large Group Methods: For Community and Organization Change . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006. Reprinted with permission.

In terms of conflict resolution, the three methods just described use many of the principles of creating common ground, acknowledging but not dwelling on conflicts, rationalizing conflict, and creating new conditions for resolution.

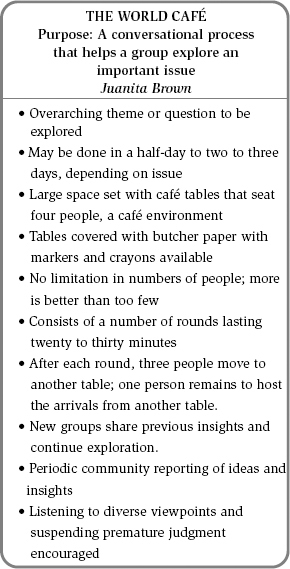

World Café (Brown and Issacs, 2005) creates several rounds of discussion on a theme among diverse stakeholder groups. This method is useful in settings with potential conflict because it does not allow people to cluster in their interest groups, but continually exposes them to different viewpoints in a very personal and relational setting.

Open Space Technology (Owen, 1992, 1995) is unique among these methods. Instead of using designed activities in preplanned groupings, it places the responsibility for creating and managing the agenda on the participants. Its founder, Harrison Owen, describes it as effective in highly conflicted situations.

Open Space creates a simple structure in which people create and manage their own discussions for one, two, or three days—for example:

- The Presbyterian Church USA invited five hundred people to an Open Space to discuss some difficult and contentious issues before the church just prior to its annual national meeting.

- A series of Open Space meetings held in Canada considered the Québecois sovereignty movement issue.

- A hospital system in California faced with the need to cut costs held an Open Space in each hospital community to hear from the community about their concerns and priorities.

This method has been used in hundreds of different venues to create good conversations about a wide range of issues.

The simplest way to describe Open Space is that it is a self-managed meeting in which those attending create their own agenda in the first hour of the event. Everyone sits in a large circle with open space in the middle. The facilitator introduces the theme of the meeting and describes the norms for participation. Then people are invited to come forward and declare a topic that they have strong feelings about so that they can convene a group to talk about it. They write their topic and name on a piece of newsprint, announce their topic to the total group, and post it on a wall called the “Community Bulletin Board.” As they post their topic, they select a time and place from the choices written on sticky notes. They place these stickies on their topic sheet and hang it on the wall. The posted topics create the visual agenda for a meeting of several days. People can add new topics whenever they want by tacking a notice on the bulletin board. Each person who proposes a topic agrees to show up and start the discussion; after it is over, they type a summary of what was said using a simple computer template. These meeting reports are printed out and immediately posted on another long wall so that everyone can keep up with what is being said in other groups.

After the initial agenda-setting meeting, the only meetings of the total group are brief circle gatherings in the morning and evening for comments and new topic announcements. The group discussion periods are usually about ninety minutes long, so there can be four or five sessions (with multiple groups convening at each session) during a day and more if the evening is also used.

A unique feature of Open Space is its rules and norms. Rather than being an event where everyone is supposed to attend everything and people feel mildly guilty if they do not, it encourages self-management and freedom to do what is needed to maintain individual focus and energy. The “law of two feet” suggests that if you are not engaged in the group you are attending, you get your two feet under you and go somewhere that is more productive. There is a lot of floating around and in and out, which is quite freeing and energizing. Other norms suggest that things begin to happen when people have energy to make them happen, so, “Whenever it starts is the right time,” and, “Whoever comes is the right people.” “Whatever happens is the only thing that could have,” and, “When it’s over, it’s over.”

Open Space removes the oughts, shoulds, and musts from meeting participation. What happens is usually quite interesting, even remarkable. An example may be helpful in getting a better sense of this unusual methodology and how conflict is dealt with. In this example of a business school in a public college, an intact organization uses Open Space three times a year to deal with long-term conflicts in the system.

The dean, then in her third year, believed that the school had fallen behind in its ability to produce “job-ready” BA graduates because faculty were using old methods, texts, and technology. Shrinking government funding had intensified the competition for resources and exacerbated interdepartmental rivalries. The faculty was unionized, as was the staff. This was a faculty that was angry at each other, at the dean, and at the administration.

Harrison Owen has said that Open Space should be used (1) for issues that affect the whole organization or system, (2) in situations of high conflict, and (3) when there seems nothing else to do. It is possible that all three reasons were part of the dean’s decision to try Open Space. The theme to be explored was “Issues and Opportunities for the Future of the Faculty of Business.” The event was held during working hours at the college over two and a half days. Fifty of eighty faculty attended, plus staff and administration. The first two days were Open Space as described above. The final half-day was a convergence process often added to the Open Space experience in order to plan for action.

In the opening agenda-setting circle, the facilitator was struck by the fact that no one looked at anyone else, often a symptom of deep conflict in a system. Although the topics posted were about the expected number, they were superficial given the theme (e.g., “the cleanliness of the college” and “academic excellence”). There was a general air of anger toward the administration. The evening news at the end of the first day was bland.

The overnight soak time clearly had an effect. The next morning, new issues were posted that were quite different from the first day, such as “conflict and conflict resolution” and “the strategic direction to get out of this mess.” The dean posted a topic, “The human face of management,” which everyone present attended. In that discussion, she talked personally about her role and views and became known to those who were present. As the day progressed, a number of individuals approached the facilitator saying things like, “You wouldn’t believe what is happening in our group!” There was excitement and energy on the second day as compared with flat affect and withdrawal on the first day.

The Open Space exploration was closed at the end of day 2 with a talking stick circle, a version of a Native American custom. The stick is passed around the circle. The person who holds it may speak if he or she chooses to, and others are expected to listen respectfully. These are not group reports but just what people are thinking and feeling at the end of the day. From the comments, it was clear that the faculty had begun to move from being frozen in conflict to another posture. Examples were, “I haven’t spoken to [another faculty member] for fifteen years because of a disagreement we had, but that is going to change.” A number reported the first meaningful conversations in years. Others talked about the need to sort out relationships and move on.

Open Space is a divergent process for allowing ideas to emerge and develop and creates really good conversations. Many people, particularly Westerners with our need for visible results and actions, add a half-day convergent structure to it in order to plan and take action. In this case, everyone voted on the issues as they emerged in the group reports, and then it was possible to name the top vote getters and form voluntary task forces around them. The group decided to hold another Open Space in four months to hear reports from the task forces and continue the conversation.

Four months later, forty-five members reassembled for another two-and-a-half-day Open Space event. This time, it opened with a ninety-minute session of reports from the task forces. Then the facilitator opened the space for new agenda items, and the meeting continued in the form described above. This time there was much more willingness to address the complex and difficult issues that they faced as a faculty trying to create a better future. Many more academic issues were addressed, as were the difficulties of dealing with departments where everyone is both tenured and out of date. Again, the last half-day was used to prioritize and organize new task forces with a four-month reporting date.

The final Open Space was run completely by the faculty, who had learned to use the methodology and made it a way of working together. Many changes have since occurred, and the faculty is continuing to work with the dean to create a secure future. One marker event that happened between the second and third Open Space is diagnostic. A dismissed faculty member tried to rally support for ousting the dean. When he went to his former anti-administration supporters, he was rebuffed and told, “This dean is the best one we have ever had.”

What principles might explain this shift in energy from being dug into conflict, blaming and attacking, to being able to problem-solve and work together? One major dynamic is the removal of the hierarchical authority structure in Open Space. There is no “they.” It is all “we.” Facilitators wait for people to create their own agenda. They believe that what is on the wall is what that group needs to talk about. Nothing is imposed. Although there is a theme, participants decide what issues they will address. The dean was there, but as an equal member of the group.

When hierarchy is absent, the well-worn patterns of manipulation and control are disrupted. There is no decision structure or way of getting power. The normal way of doing business is suspended, and people are asked to follow their own energy and commitments so that they both get and give. In Open Space, the law of two feet and the four principles replace hierarchy with guidance that creates huge freedom to act in ways that are both delightful and anxiety provoking. But everyone is in the same situation, and people enjoy exploring their freedom and work it out. It leaves the participants with one critical question: What is it that we have energy for and the will to do?

Embedding New Patterns of Collaboration

What is the impact of participatory meetings of the whole system after the event is over? What happens back at work? There is anecdotal evidence that one meeting of this type can create new plans and get action going that has a strong impact on the system. Another big effect of all of these methods is to create useful new networks and relationships. In the case of the business school, faculty began to use Open Space as a way of working together. When this happens, hierarchy and the bureaucratic processes in the organization are modified.

We want to strongly point out that senior management’s understanding of the collaborative nature of these meetings is crucial. They need to understand and agree to this method of working and provide strong sustained leadership of the process from the beginning.

What we see in the business school case just described is the transfer of or embedding of new patterns of working together and relationship management from the large group event into the workplace. This truly is a culture change. The movement in the business school was from hostility and suspicion to collaboration and a more productive and satisfying workplace. With strong, persistent leadership over time, there is growing evidence that it is possible to shift the culture of organizations from polarized and conflicted to much more collaborative and productive.

NEW FRONTIERS: APPLICATIONS TO PEACE BUILDING AND LEGISLATIVE PROCESSES

We now focus on two emerging areas of large group application: peace building and legislation. Peace-building applications are quite numerous, while legislative applications are just emerging. The term peace building , increasingly in evidence in recent years, describes outside interventions that are designed to prevent the start or resumption of violent conflict within a nation by creating a sustainable peace. The practice is a close cousin to the more narrow concepts of rack II or multitrack diplomacy that have evolved since the 1980s and refer to informal negotiation processes between stakeholder groups of a conflict. Legislation, or rule making of rights and responsibilities, is one way we resolve differences, manage conflict, and keep the peace. Like peace building, it is proactive prevention because the rule of law reduces volatility and is a critical step forward for countries that have relied on power and force to resolve their differences.

Over time, the history of conflict management and resolution has moved from the use of hierarchy and force by those in power to the use of rights, rules, and due process in courts and tribunals, to focusing on interests and needs in more informal negotiation and mediation processes. We see this trend reflected in organizational dispute resolution and also in all realms of governance—executive, judicial, and legislative. With it has also come a reduced dependence on an authority to resolve or manage the conflict and a greater responsibility of the constituency to take charge of the situation that affects them. Large group methods, with their high participation and inherent democracy, seem to be a logical extension of this trend.

The traditional approach to diplomacy and the resolution of international deadly conflict is to address disputes hierarchically through military interventions, high-level negotiation or mediation, or UN resolution. The focus has been more on content than process, with many subject matter experts devising a solution. The conventional approach is to meet in small formal negotiating groups with a fixed agenda. The underlying tone is one of competition and power, not about building understanding and creating cooperation. Even if high-level negotiators are intent on bringing a collaborative strategy to the process, the fact that they are representatives will mean at best that they have to sell the agreement to their constituency or, at worst, look like traitors for talking to the other side. Similarly, the parties at the table can often be those who are most polarized and often entrenched in identity politics.

Large group methods are designed to create a collaborative rather than a competitive climate. All of the stakeholders are in the room, reducing the need to sell outcomes. All views can be represented—the extremes, the moderates, the more silent ones. When a large group comes together to create a Common Future agenda, many of the short-term subgroup disputes disappear when a longer-term vision that is more compelling comes into view. Good facilitation of these methods enables the presenting polarities to give way to deeper affinities, and the passion surrounding the immediate impasse may fade or take new form. Large group methods allow more than just a negotiated settlement between polarized groups; they promote the creation of a common ground agenda for the whole system. And by making the facilitator less prominent and the participants more empowered, they engage each participant’s innate capacity for cooperation and responsibility to resolve the conflict.

The benefits of large group methods for intergroup deadly conflict also apply to rule making. The American legal system is based on the benefits of the adversary process—the idea that out of polarization of the issues comes objective truth. Those who facilitate large group methods understand that looking for common ground rather than highlighting difference may be a far more efficient way of managing difference and moving forward. Legislative applications of these methods could provide a hopeful alternative to political processes that in many parts of the world are often highly adversarial and frequently lead to impasse.

We now turn to a few case descriptions to show how these methods are being used in peace-building and legislative settings and suggest possible ways that their application might be extended.

Applications to Peace Building

One of the early applications of a large group method to violent intergroup conflict was in early 2000, when Coleman was asked to provide collaborative negotiation training and then mediation to about thirty political representatives from the PUK and KDP parties in Iraqi Kurdistan. 1 These two groups had been in armed conflict with each other, resulting in losses on both sides. The US State Department was interested in building collaboration among them to unite against Saddam Hussein. For our part of the initiative, we were given five days. On the first three days, we delivered collaborative negotiation training, which did a lot in and of itself to create a collaborative climate in these two groups (for a detailed description see Holman, Devane, and Cady, 2006). The last two days, in lieu of mediation or mediation training, Open Space was used with a focusing theme: “Building Collaboration among Us: Issues and Opportunities.”

Open Space was a greater success than could have been imagined. Not only did the representatives of the two sides end up with their arms around each other singing Kurdish songs, the process resulted in the creation of a bilateral conflict resolution center that supported on-the-ground collaboration in many ways, including the use of Open Space as a process for high-conflict problem solving, much more collaboration between the two sides, and the rollout of many more Open Space and other large group processes around the world.

Zachary Metz, then a graduate student at the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) at Columbia University and part of the team in this initiative, took the Kurdish example and has replicated versions of it in Iraq, Thailand, Burma/Myanmar, Northern Ireland, Lebanon, and East Timor. Metz, now in private practice and adjunct faculty at SIPA, was one of the first to identify his work as peace building. Generally the work is sponsored by governmental organizations or foundations with the intention of addressing violent intergroup conflict. Methods used have included Open Space, Appreciative Inquiry, and versions of the Public Conversations Project dialogue process. Typically in these situations, the people in the room are highly stratified and polarized along political, social, and national identities. There are also security challenges of bringing a large group of people together in war-torn areas as they become an easier target and often need to change venues on a moment’s notice. Metz regularly reports great success with these methods, in that they often effectively create new communication dynamics and transformative interactions amongst polarized groups.

The examples are joined by many others:

- In working with Mediators beyond Borders in 2012, Loretta Raider and Debey Sayndee applied an adapted Future Search design to quell political violence resulting from elections in Sierra Leone.

- Harrison Owen, Avner Haramati, Carol Daniel, and Tova Averbruch have used applications of Open Space on multiple occasions to bring together Palestinians and Israelis.

- John Engle in Haiti successfully convened dire enemies in the same room in an Open Space process to preempt violence resulting from the assassination of an elder statesmen.

We suspect there are hundreds more of these stories of using large group methods to build peace and address violent conflict.

Admittedly the examples are often events more than an important component of an integrated peace-building process, but this does not have to be so. Building peace has been and often is an elite process that has been conducted at high levels by famous people such as Jimmy Carter, Nelson Mandela, F. W. de Klerk, and Kofi Annan. Indeed, many prominent people have made it their post-office mission to provide trusted mediation expertise to stakeholders of violent intergroup conflict. We applaud these efforts and believe they could be greatly strengthened with simultaneous large group engagements at multilevels in the system in question. The mediation effort could engage not just other high-level leaders, but midlevel influentials as well as the grassroots, to create a more broad-based effort to build common ground.

Applications to Legislative Processes

The exploration of applications of large group methods to legislation and the political process is just beginning. Here are a few examples from the field that show the promise.

After two years of fighting over how to spend a $1.5 billion legislative entitlement to build highways on tribal and public lands and getting nowhere, federal, state, and citizen stakeholders came together in an Open Space facilitated by Harrison Owen. If the fight was not resolved, the money would go back to the US Treasury. Three stakeholder groups convened: one-third Native American, one-third from the federal government, and one-third from state and local governments. What they could not do in two years, they did in two days in Open Space and reached an agreement all could live with.

Coleman is currently working with a parliamentary body that is interested in using these methods to make rules. Codex, a global body not unlike the UN General Assembly, is charged with reaching consensus on global standards that protect consumer health and fairness in global food trade. 2 Traditionally, Codex has done this through informal negotiations prior to a parliamentary vote. In recent years, however, intense polarization around issues such as genetic modification and the use of growth hormones in meat is causing this body to seek alternative methods of dispute resolution, including large group facilitation processes to build common ground.

A final example was the use of Open Space in 2003 by the Scottish parliament as an alternative to adversarial hearings. Kerry Napuk facilitated a successful event in Glasgow for the Social Justice Committee. It involved three committee members and seventy-four stakeholders working in the area who felt the process gave them an immersion course on the issues and allowed them to vote on priorities. Subsequently, with Kerry’s help, Fay Young created Leith Open Space (Leith is a district of Edinburgh), which regularly convenes the community of Leith in Open Space with elected officials including members of Parliament (www.leithopenspace.co.uk ).

The values of large group processes—participatory democracy, transparency, direct involvement—lend themselves to legislative environments. But politicians and political institutions are often risk averse and slow to change. Trends toward deeper democracy will ultimately bring the usefulness of these methods into clearer view. So will the recognition that, as Harrison Owen reflects, much of the work of legislation takes place informally “in the hallways” anyway. The greater use of large group methods would acknowledge this reality by providing state-of-the-art processes to support the hard work of reaching agreement.

CONCLUSION

Practitioners of large group methods have created processes that work at the organizational, community, and intergroup levels to manage or resolve conflicts. Here are eight principles about large group processes that account for their effectiveness:

- Focus on common ground , areas of agreement, rather than differences or competitive interests.

- Rationalize conflict . This means acknowledge and then clarify conflict rather than ignoring or denying it. Agree to disagree, and move on to areas of agreement.

- Expand individuals’ egocentric views of the situation by exposing them to many points of view in heterogeneous groups that do real tasks together collaboratively and develop group spirit. This broadens views and educates.

- Promote the development of personal relationships through structures such as small table groups that exchange information and views with each other in structured activities. (A sense of having a personal relationship helps manage differences.)

- Allow time to acknowledge the group’s history of conflict and feelings before expecting people to work together cooperatively.

- Manage the public airing of differences and conflict . Treat all views with respect. Allow minority views to be heard but not to dominate. Preserve time for the expression of views of people “in the middle,” as well as those who are more extreme.

- Manage conflict by refocusing incendiary issues on issues that can be dealt with in the time available.

- Reduce hierarchy as much as possible. Push responsibility for working together and for managing conflict down in the system so that people are responsible for their own activities.

Large group methods tackle conflict in different ways at different points in its development—sometimes dealing with past history, sometimes putting differences aside and simply managing them, sometimes directly addressing and resolving issues that divide people and groups. These eight principles are primarily at the systems level. These processes, however, simultaneously affect the group and the individual level as reflected in principles 3 and 4. These methods also document many of the principles developed in the research on conflict and conflict resolution. We can hope that they may also stimulate new theoretical thinking about how conflict is managed and resolved.

Notes

References

Axelrod, E., and Axelrod, R. The Conference Model . San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2000.

Brown, J., and Isaacs, D. The World Café: Shaping Our Futures through Conversations That Matter . San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2005.

Bunker, B. B., and Alban, B. T. (eds.). “Large Group Interventions.” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 1992, 28 (4).

Bunker, B. B., and Alban, B. T. Large Group Interventions: Engaging the Whole System for Rapid Change . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997.

Bunker, B. B., and Alban, B. T. (eds.). “Large Group Interventions.” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 2005, 41 (1).

Bunker, B. B., and Alban, B. T. The Handbook of Large Group Methods: Creating Systematic Change in Organizations and Communities . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2006.

Dannemiller Tyson Associates. Whole-Scale Change: Unleashing the Magic in Organizations . San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2000.

Emery, F. Participative Design for Participative Democracy . (Rev. ed.) Canberra, Australia: Australian National University, Centre for Continuing Education, 1993.

Emery, M., and Purser, R. E. The Search Conference: A Powerful Method for Planning Organizational Change and Community Action . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1996.

Holman, P., Devane, T., and Cady, S. The Change Handbook . Berrett-Koehler, 2006.

Kleiner, B. H. “Open Systems Planning: Its Theory and Practice.” Behavioral Science , 1986, 31 , 189–204.

Jacobs, R. W. Real Time Strategic Change . San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1994.

Klein, D. “Simu-Real: A Simulation Approach to Organizational Change.” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 1992, 28 (4), 566–578.

Ludema, J. D., Whitney, D., Mohr, B. J., and Griffin, T. J. The Appreciative Inquiry Summit: A Practitioner’s Guide for Leading Large-Group Change . San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2003.

Lukensmeyer, C. J., and Brigham, S. “Taking Democracy to Scale: Large Scale Interventions—For Citizens.” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 2005, 41 (1), 47–60.

Owen, H. Open Space Technology: A User’s Guide . Potomac, MD: Abbott, 1992.

Owen, H. Tales from Open Space . Potomac, MD: Abbott, 1995.

Spencer, L. J. Winning through Participation . Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt, 1989.

Weisbord, M. R., and Janoff, S. Future Search . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995.