CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

SOCIAL NETWORKS, SOCIAL MEDIA, AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION

a

James D. Westaby

Nicholas Redding

Research on social networks has seen exponential growth in the social sciences since the turn of the twenty-first century (Knoke and Yang, 2007; Watts, 2004). The network approach also has considerable value for conflict scholars and practitioners because it provides a unique set of metaphors and tools that can help describe social conflicts. In this chapter, we first provide an overview of traditional social network analysis and then review a number of studies using social network concepts to understand conflict and the role of social media in conflict settings. We next demonstrate how new concepts in dynamic network theory may provide a deeper psychologically based explanation of social conflicts (Westaby, 2012), which can also inform conflict resolution strategies. By infusing goals into social networks, dynamic network theorizing provides social scientists and practitioners with new ways to conceptualize conflict.

TRADITIONAL SOCIAL NETWORK ANALYSIS

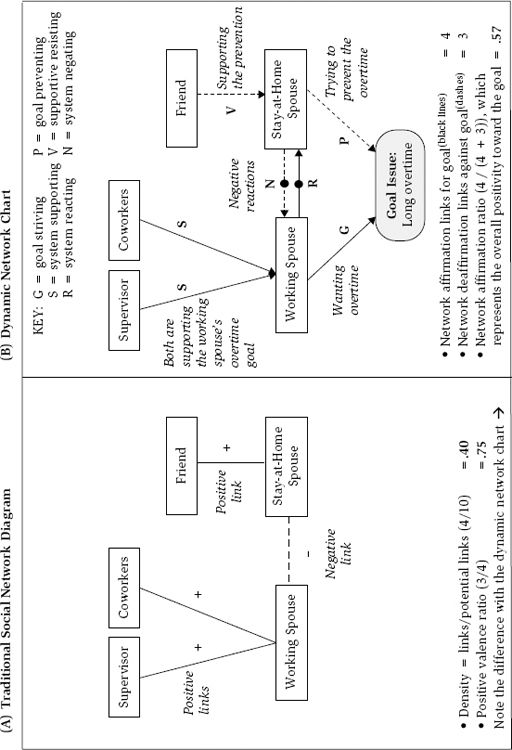

Social network concepts allow us to methodologically describe the structural linkages among entities (Newman, 2003; Wasserman and Faust, 1994). Figure 41.1a illustrates a traditional social network analysis of a small social network interacting around a working and a stay-at-home spouse. In this illustration, five individuals have various links with one another. These charts have considerable appeal for describing basic connections among people, and social scientists have generated an array of statistics to describe the interactions in these case studies (Balkundi and Kilduff, 2006). For instance, the concept of density indicates the number of observed links divided by the number of total possible links in the network. In figure 41.1a , there are four links divided by ten possible linkages, which results in a network density of .40. When this number approaches 1, it represents a network where everyone is densely connected to one another and implies a strong form of interdependence. When the metric is near 0, it illustrates a social network where no one is connected and implies independence among actors.

Figure 41.1 Network Chart Comparisons

Sociologists have developed other metrics to describe social networks as well (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). For example, centrality typically represents how information flows through central individuals in social networks. In figure 41.1a , you can see that the working and stay-at-home spouses are more centrally located in the network than others. When the centrality indicators approach 1, it often suggests that information is flowing through key individuals in the system, such as the spouses in this case. Another important conceptualization in the social network literature is that of structural holes (Burt, 1992), which represent “gaps in the social world across which there are no current connections, but that can be connected by savvy entrepreneurs who thereby gain control over the flow of information across the gaps” (Kilduff and Tsai, 2003, p. 28). The concept that weak links can be powerful (Granovetter, 1973) also illustrates situations where people can leverage their weak contacts with others to facilitate social capital in their lives. For example, by engaging in even a brief conversation with your new neighbor, you could create a weak link, which may facilitate your social capital in the future. However, this line of theorizing does not sufficiently differentiate how various types of links may have different effects (e.g., a weak hostile link could have an adverse impact on such capital), which can be important according to dynamic network theory (Westaby, 2012).

The principle of homophily is relevant to some conflict settings as well. Homophily often refers to the tendency for people to interact and connect with similar others. Kupersmidt et al. (1995) showed how similarity between individuals increased their likelihood of being friends. In contrast, the ties between people that are not similar to one another are more vulnerable to decay, which can set the stage for social niches to form (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook, 2001). However, such dissimilarity need not always lead to conflict. Dynamic network theory (Westaby, 2012) illustrates that there are many situations in which people are willing to work with and support others that are not similar to themselves in pursuit of common goals.

Finally, in line with assumptions that people are motivated to maintain structural balance in their interpersonal relations and cognitions (Cartwright and Harary, 1956), researchers often look at the generic positive and negative valences people have with one another and then make assumptions about the entire system. In other words, if we know how many positive and negative links exist in a social network, we may presume that we can understand how much overall conflict and cooperation there is in the system. For example, in 41.1a, you can easily see that the working and stay-at-home spouses have a negative relation with each other (the dashed path), which implies an interpersonal conflict. All other linkages have positive valences in the system (the solid paths). From this orientation, the ratio of positive to negative valences is .75 in this example, implying a generally positive system of interpersonal relations. Although mapping valences in this way is a common approach for studying interpersonal relations and is presumed to model the true motivational forces of full systems, it has the potential to oversimplify the underlying motivational and conflicting forces in the network. Dynamic network theorizing that incorporates goals provides an alternative perspective as illustrated below. Overall, traditional social network perspectives benefit both researchers and practitioners of conflict resolution by encouraging the assessment of conflict in broader social systems instead of focusing on the primary parties involved in the conflict.

SOCIAL NETWORK RESEARCH ON CONFLICT

We now review research findings regarding traditional networks and conflict. Although not an exhaustive review, this includes a sampling of research at different levels of analysis. First, in a study of 2,348 married or cohabitating adults, Walen and Lachman (2000) found that networks with higher levels of support reduced harmful effects during strained interactions. They also found that women benefited more from friends and family than men did. From another vantage, Vanbrabant et al. (2012) found a positive association between personal social network size and reported verbal aggression, controlling for extraversion, neuroticism, and gender. Neal (2009) examined the peer social networks of third through eighth graders, looking specifically at the location of aggressive children in terms of network centrality and density and how these variables were associated with relational aggression. Results indicated that network density was positively related to relational aggression. In contrast, in a study of sixth graders, Mouttapa, Valente, Gallaher, Rohrbach, and Unger (2004) found that children who were friends with a bully (self-reported) were more likely to self-report bullying behavior themselves and less likely to report being a victim of bullying.

Social network analysis has been applied to understanding a variety of negative group dynamics as well. One study examined conflict within groups in terms of adversarial networks (Xia, Yuan, and Gay, 2009). Not surprisingly, these researchers found that group members who have more negative evaluations of other group members are less satisfied with the group. As for psychological dynamics in groups, research has shown that task conflicts can have a positive effect on groups performing complex tasks as compared to routine tasks, but relationship conflicts have a negative effect (Jehn, 1995). Curşeu, Janssen, and Raab (2011) extended these findings by identifying network structures that minimize destructive conflict in groups. They suggest that work groups can maximize the benefits of conflict in teams by dividing groups into subgroup task units while minimizing the destructive elements of relationship conflict through training in communication and interpersonal skills.

de Dreu and Gelfand (2008) have pointed out that organizations today operate in an interorganizational network that has a strong influence on personnel selection, managerial techniques, and technologies, all of which play a role in conflicts and tensions in an organization. These conflicts often manifest internally as environmental pressures exert uneven influences on different aspects of the organization. As for leadership in organizations, Balkundi, Barsness, and Michael (2009) found that leaders who were frequently sought out for advice reported lower incidents of team conflict.

Labianca, Brass, and Gray (1998) found that individual perceptions of high intergroup conflict in an organization were related to negative relationships across groups, indirect negative relationships through friends in the organization, and low intragroup cohesiveness. Using simulations, Krackhardt and Stern (1988) found that organizations with a higher density of friendship links that extended across subgroups outperformed those where friendship networks were most dense within subgroups.

SOCIAL MEDIA

The past two decades have seen unprecedented innovation in social media technology and services that facilitate digital communication between individuals, groups, organizations, and nations. According to Hughes, Rowe, Batey, and Lee (2012), “social networking sites (SNS) are quickly becoming one of the most popular tools for social interaction and information exchange” (p. 561). For instance, at the time of this writing, among all US adults, 66 percent use at least one social networking site (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn, or Google+), and 48 percent visit these sites as part of their typical day. Facebook, launched in 2004, is currently the most popular digital social networking service. As of September 2012, the number of monthly active users of Facebook worldwide reached 1 billion, with Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, and the United States being the top five countries in terms of membership numbers (Facebook, 2012). That means that roughly one in seven global citizens is using the service in some capacity. Twitter is also a popular social media website, and it is likely that a variety of new services will emerge in the future as competition increases in this expanding market. Although there are reasons to suspect that these online tools would reduce conflict through increased social interaction and the ability to express views regardless of geographic location or social stratus, it is also likely that the increased availability of these communication tools, combined with the ability to remain anonymous, may serve the opposite effect (Bargh and McKenna, 2004).

Early experimental research on computer-mediated communication showed that users participated more equally, were able to more quickly shift positions on topics or decisions, and were less inhibited than when communicating face-to-face (Kiesler, Siegel, and McGuire, 1984). Today there are countless spaces online where individuals can form virtual groups for discussion and sharing ideas, including places to help resolve conflicts. While many of these groups may function well, there are frequent examples of online interactions that escalate into destructive, counterproductive dialogues (Lee, 2005; Moor, Heuvelman, and Verleur, 2010). Lee (2005) has illustrated various ways that social media users deal with hostile situations online, such as competitive strategies (e.g., flaming and denouncing), avoidance approaches (e.g., withdrawal), and cooperative tactics (e.g., showing solidarity, apologizing, and mediating).

Some research has shown how online social networks can complicate relationships. For example, Papp, Danielewicz, and Cayemberg (2012) found that disagreements among couples as to whether the relationship status should be shared on Facebook was associated with decreased relationship satisfaction for women but not men. Some researchers suggest that sites such as Facebook also make it easier for an individual to obsessively observe someone without his or her consent, especially the case for former romantic partners (Chaulk and Jones, 2011; Lyndon, Bonds-Raacke, and Cratty, 2011), as well as promote jealousy in current relationships due to online monitoring of the partner’s activities (Muise, Christofides, and Desmarais, 2009).

Cyberbullying is also becoming a serious concern. Mesch (2009) reported that adolescents who have active profiles on social networking sites or who participate in online chat rooms are more likely to be bullied. In a survey of 756 Turkish middle school students, males indicated engaging in more cyberbullying than females, and students were often not aware of effective strategies for bringing cyberbullying issues to adults (Yilmaz, 2011).

Defamation on the Internet and on social media is another serious source of conflict and interpersonal hardship, and there are few standardized ways to deal with its presence. For example, some individuals may take advantage of freedom of speech values (e.g., implicitly or explicitly endorsed by a website’s policy) by making false accusations about others in efforts to tarnish or destroy their reputations. Some may even do so to promote their competing products or ideology. This is often made possible when website platforms do not sufficiently vet posted information or do not remove abusive information, have insufficient guidelines to avoid defamatory situations, and do not verify (or post) true identities. Complicating matters further is when such defamatory accusations are made anonymously without verifiable evidence. In such cases, it is difficult to hold the accusers accountable for their commentary, which may remain online indefinitely. Some of the ways that people could manage these escalated situations is to pursue legal action against the websites or the individuals posting such material online (if they can be identified through court action or digital tracking). This can be a costly and emotionally laborious process. Various people have described the current state of affairs on the Internet as the “wild west” (Hundley and Anderson, 1995), which implies that some people may become victimized by others who exploit systems or take advantage of poor accountability. A related issue of conflict concerns privacy of information. Given that communications and images are held in digital form online, conflicts arise in terms of how that information is used by third parties. Large-scale conflicts can arise when important digital information is lost, stolen, or sold without permission.

Relevant to new advances in online gaming technology, Ferguson (2010) highlights the implications of massive multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG). These games often include violence toward fictional characters, but at the same time promote complex social interactions between individuals, even individuals who would otherwise be challenged in social situations, which allows whole online social communities to develop. However, because research has shown that violence on TV can affect aggressive behavior (Bushman and Huesmann, 2006), much more research is needed to evaluate MMORPGs.

Even basic e-mail conversations can contribute to the escalation of network conflicts. Friedman and Currall (2003) suggest that the nature of e-mails is asynchronous, which means that e-mail correspondence is not a conversation but instead a back-and-forth exchange of statements. It is also text based, which means it lacks the facial expressions of face-to-face or videoconferencing interactions and verbal intonation and nuance that would be present in a telephone conversation. This can contribute to misunderstanding. However, e-mail allows people to delay responses and take more time to review and revise their messages for accuracy. Turnage (2007) suggests several ways to deal with these pitfalls such as “netiquette” training programs.

In communities around the globe, many youth represent the wired generation of individuals who have connected and engaged in ways never before possible, which allows entirely new ways of organizing and exercising participatory citizenship roles (Herrara, 2012). Social media may also play an important role in how citizens take action when they become dissatisfied with their governments. For example, in Egypt, early social media use among youths was primarily in the form of blogging. The extreme popularity of blogging was soon supplanted by the introduction of Facebook, which saw membership grow from a little over 800,000 in 2008, to 5.6 million three years later, with 2 million users joining Facebook during the first few months of the Arab revolutions (Herrera, 2012). Facebook may have allowed many youth to organize much more effectively than blogging because of the ability of individuals to create groups, Facebook pages for various issues, and mass invites for Facebook members to attend events (such as sit-ins, protests, marches, and strikes). In addition, Twitter may have provided protestors with an effective way of quickly engaging foreign media, and the media were able to provide more comprehensive and moment-to-moment reporting of events in real time (Lysenko and Desouza, 2012).

Online communication tools such as Twitter also offer a promising new platform for researchers to explore large-scale conflict dynamics. Not only are various forms of data publicly available, but the data often represent an aspect of the actual network of communications characterizing the situation. Scholars can use these data to analyze international conflicts dynamically because people on the ground are disseminating information about events that are occurring in their communities in real time. For example, Zeitzoff (2011), using content from Twitter and other social media sources, was able to measure the military responses of Israel and Hamas during the 2008–2009 Gaza conflict to identify important turning points in the conflict: the movement of Israeli troops into Gaza and the UN Security Council vote calling for an immediate cease-fire. As social media tools proliferate, researchers will have more opportunities to conduct studies like this, mapping complex large-scale conflict dynamics as they unfold.

DYNAMIC NETWORK THEORY

Although traditional social network concepts have been incredibly helpful in showing how people are linked to one another in various ways, they have lacked a deeper integration of psychologically based goal pursuit and intention concepts, which are often presumed to be critical drivers of human action (Ajzen, 1991; Westaby, 2005; Westaby, Probst, and Lee, 2010). This psychological void may be a concern because many human conflicts result from tensions originating with people’s opposing goals, desires, and aspirations (Deutsch, 1977). Hence, accounting for goals in social networks is critical to advancing our understanding of how conflicts can be addressed and resolved. Fortunately, new advances in the dynamic network theory of goal pursuit (Westaby, 2012) explicitly address how social networks are involved in fundamental goal pursuits, which has implications for the study of conflict and its resolution.

What’s New and Different?

A unique feature of dynamic network theory (Westaby, 2012) is that it articulates how only eight social network role behaviors are critical to explain how social networks are involved in goal pursuits and human aspiration. We illustrate these roles in the context of a network having a work-family conflict generated by a working spouse with a strong desire or goal to work a lot of overtime. In this case, the working spouse is considered a goal striver toward working overtime (G) in the theory. The spouse is also receiving a lot of support for working overtime from a supervisor and other coworkers at the firm (who are perhaps swamped at work). These entities are referred to as system supporters (S) in the theory. These linkages and their labels can be seen in the dynamic network chart in 41.1b. The theory predicts that systems that have considerable goal striving and system supporting (more generally referred to as network motivation) will have higher levels of success in reaching their target goal, especially when they are competent in their actions.

In contrast, social conflict can arise in social systems through network resistance , such as emanating from the stay-at-home spouse who is trying to stop the overtime. This is referred to as goal prevention role behavior in the theory (P) and is shown with dashed paths to goals. If this spouse has others in the network supporting the resistance, referred to as supportive resistance (V), it shows how other entities in the network are helping fuel forces against the goal and thus how a wider conflict can exist in the social network. This is also depicted in 41.1b with dashed paths between relevant parties. Greater goal preventing and supportive resisting in a social network is predicted to have a larger effect on thwarting the target goal pursuit. Ironically, the individuals in some of these conflict settings may not show any hostility or aggression toward one another, such as two professional athletes engaged in a tough match who share no animosity toward each other (or may even be friends). Hence, dynamic network theorizing allows for such nuanced relations, instead of relying on assumptions that goal prevention and supportive resistance behaviors always have hostile or aggressive intent.

In other cases, interpersonal negativity, such as hostility, prejudice, and aggression, can coexist with goal prevention (e.g., a hostile competition). Dynamic network theory refers to such interpersonal linkages that contain such affect-based hostility, negativity, or prejudice as, first, system negation (N), to represent a person’s negativity toward another’s goal pursuit. Second, system reactance (R) represents a person’s negativity toward another’s resistance toward the goal pursuit. To illustrate these concepts in our example in figure 41.1b , the stay-at-home spouse shows system negation toward the working spouse’s desire for overtime (i.e., is upset about it), while the working spouse is reacting to this by showing hostile negativity back to the spouse because of the resistance. 1 This example illustrates how a mutual conflict in the social network has formed in relation to the underlying goal issues about overtime work. That is, system negation has formed in conjunction with goal prevention. More broadly, research has shown that negative social network ties in general are related to increased psychological distress (Finch, Okun, Barrera, Zautra, and Reich, 1989) and lower life satisfaction (Brenner, Norvell, and Limacher, 1989), although much of this research has not unpacked how these negative links are related to underlying goal prevention and/or system negation, which we presume are often independent dimensions that may be correlated in some contexts.

Finally, there may be other ironic effects of goal prevention and supportive resistance on conflict resolution processes. For example, these behaviors could represent constructive forms of conflict resolution when they successfully prevent others from pursuing actions that ironically inhibit them from securing other more valuable goals and outcomes, such as a negotiator getting another person to see that the counteroffer will actually result in more positive outcomes for the person than the initial offer.

More generally, besides providing a new approach to understand social connections, dynamic network charts also allow scholars and practitioners to describe overall dynamics in social systems. For example, the network affirmation ratio shows the overall ratio of positive to negative forces involved in goal pursuits. This value was .57 in the work-family conflict in figure 41.1b , illustrating that considerable conflict exists in this system in relation to the overtime issue. It is here where we can see potentially sharp differences between traditional social network diagrams and dynamic network charts. For example, the traditional network approach (without goals) indicates that the overall ratio of positive to negative valences in figure 41.1a was .75. This represents a rather positive system and a substantively higher value than .57 in the dynamic network chart, which represents a system with considerably more conflicting forces that in some intractable contexts may accumulate over time (Coleman, 2011; Gottman and Levenson, 1992).

How do we explain this difference? On closer inspection, we see that although the friend and stay-at-home spouse’s linkage is positive in the traditional network approach, this linkage is actually a set of behaviors that is supporting the stay-at-home spouse’s resistance to others wanting to pursue overtime. Although the friend and stay-at-home spouse have a generally positive link with each other, this link is a force working against others in the social network wanting the overtime. Hence, the traditional network approach is potentially oversimplifying the system and overestimating the positivity ratio when we look at a key issue in the system. The dynamic network chart, in contrast, can unpack how people are working with (or against) one another toward their different goals and desires, which may provide a deeper understanding of human conflict forces operating in a systemic context (Lewin, 1951).

Finally, although not shown in figure 41.1b for simplicity, dynamic network theory also illustrates that people in peripheral roles can have an impact on goal pursuit and human conflict processes. In particular, interactants (I) are people who are interacting around others in goal pursuit but not helping, hurting, or even observing what is going on in the system. For example, a child may be interacting around the spouses but is not paying attention to their discussions about overtime at work. Such interactants can also change conflict dynamics inadvertently, such as the two spouses toning down their disagreement about overtime when the children are nearby. This interaction may also introduce additional goals into the system. For example, a child may remind the couple of their positive interdependence and love, which in turn would decrease the relative importance of the work-conflict issue. Observers (O), the last role in the theory, represent people watching, listening to, or generally observing a given goal issue or conflict between people but not helping, hurting, or interfering with the situation. For example, a cousin may have heard about the conflict between the spouses but did not take a position either way. People in peripheral roles can also be targets for change in conflict resolution strategies. For instance, the working spouse may ask the cousin to support the overtime and try to change the stay-at-home spouse’s mind about it. 2

The Network Rippling of Emotions

Dynamic network theory also proposes how emotions and hostilities spread in networks through the network rippling of emotions process (Westaby, 2012), which is important in explaining how relational conflicts can start. This process illustrates how goal achievement or goal progress (or a lack thereof) affects the spreading of emotions to specific people in social networks. To illustrate, when goal strivers achieve their goals or desires, they are expected, not surprisingly, to feel positive emotions about the success. But if these goal strivers also had system supporters (even among those in out-groups), these supporters would be expected to have positive emotional reactions in regard to the goal striver’s success, such as a parent feeling good about his or her child’s winning an award in a heated competition. Here, one can see that emotions in the network are contingent on the goal and are directed in systematic ways.

In contrast, if goal preventers, supportive resistors, or system negators exist in the same system defined around a given goal issue, they would be expected to experience negative emotions such as frustration, envy, or jealousy when others are achieving the goals they wanted to resist. For example, both the child who lost the heated competition and his or her parents would likely feel negative emotions and target some of this negativity and frustration toward those on the winning side. It is here where interpersonal negative links now exist. This hostility may be direct, such as confronting the other family, or indirect, such as gossiping malevolently about them. Such triggers can also set the stage for potentially longer-enduring or even intractable conflicts between people (with negative attractor states) unless these negative orientations can be destabilized or reconciled (Vallacher, Coleman, Nowak, and Bui-Wrzosinska, 2010).

The theory also delineates that generalized conflicts can exist among entities in social networks even when there is no previous interaction or direct goal prevention. For example, some people may have preconceived stereotypes and prejudices about others, based on their group classification or identity, even though they have never interacted before. Or people may believe negative things they hear about others through third-party gossiping—even things that may be groundless in fact. In these cases, individuals and groups can learn and develop system negation, distrust, and prejudice without having been involved in one another’s lives.

CONFLICT RESOLUTION STRATEGIES IN SOCIAL NETWORKS

In this section, we illustrate how practitioners could use dynamic network concepts to portray conflicts and use such information for facilitating change. In the traditional social network approach, a practitioner would often enter network data into a computer program (such as through an adjacency matrix) to understand how people are positively or negatively linked to one another, as illustrated in figure 41.1a . Computer programs then provide visuals that allow practitioners to see all the linkages between entities. Although visually interesting, the data can be overwhelming to understand when the network becomes large, with many boxes and numerous lines. Fortunately, as an alternative, researchers or practitioners could also focus on calculating statistics about each of the entities (i.e., an egocentric analysis) to gauge their presumed importance in the system, especially their level of centrality (Balkundi and Kilduff, 2006). A traditional network approach often assumes that the entities that are most central are critical to target in an intervention.

While this makes intuitive sense at first glance, there may be some difficulties in implementation when compared to other approaches. To illustrate, in figure 41.1a , the working spouse is most central in this simple network because he or she has the most connected linkages. Thus, a traditional network approach could suggest that this is the primary entity to target with the intervention. However, such an approach, void of other motivational orientations in the conflict, may not steer an intervention effectively. For example, according to dynamic network theory, an intervention must include both the working spouse and stay-at-home spouse because they are not only negatively reacting to one another (N and R), they are both equally and directly involved in their goal-related conflict about working overtime (G and P). The theory therefore provides additional guidance to understand key motivational orientations in networks, which can be used to inform interventions.

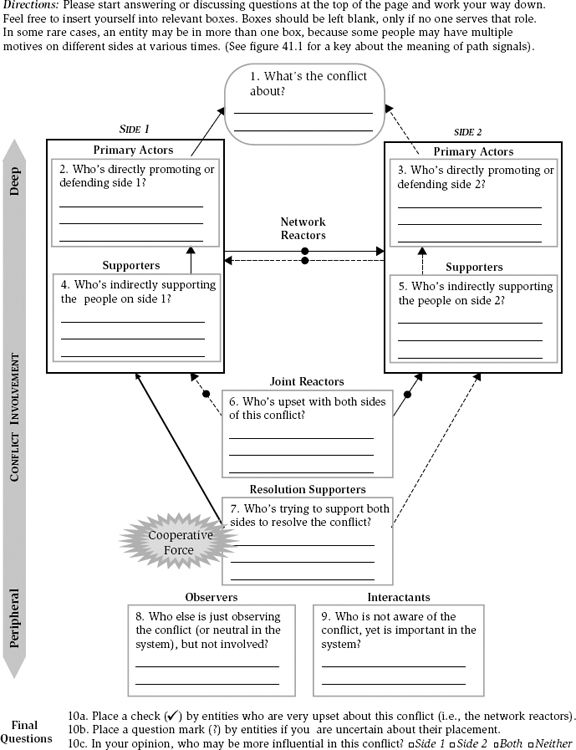

NETWORK CONFLICT WORKSHEET

Another concern that practitioners face when using social network diagrams and even fully detailed dynamic network charts is the laborious nature of using these methods in practice. Fortunately, because dynamic network theory can capture critical motivational parameters involved in network conflicts, it can provide another parsimonious approach, which we introduce in this chapter. Specifically, figure 41.2 presents a network conflict worksheet that may be helpful for gaining a system perspective about how multiple social network entities are motivationally involved in a network conflict. This initial formulation, which needs further refinement, could provide practitioners with a basic method of conflict analysis from a network perspective. This tool could also be used in conjunction with other tools of assessment, such as those assessing the parties’ values, interests, and objectives. To process the worksheet, researchers or practitioners could use the worksheet to collect information confidentially from individuals in the network. Or the worksheet could be used to facilitate group discussions by initially breaking the groups into different sides of the conflict to minimize overt conflict between parties and then later bringing the sides together to develop a deeper understanding of the complexities of the conflict once a professional facilitator processing the information deems it safe and ethically appropriate. That is, researchers or practitioners should be very careful about the way in which identities, general descriptors, or pseudonyms are used in discussions, reports, or data presentations based on ethically appropriate choices for information sharing. In sensitive settings, it may be prudent for mediators, for example, to use the information collected confidentially (or anonymously) from individuals using the worksheet to help understand the social context and brainstorm solutions, but not to share how individuals responded to the worksheet in public.

Figure 41.2 Network Conflict Worksheet

Before describing the worksheet, there are important considerations to keep in mind. At first glance, it would appear that the worksheet forces the practitioner to limit the conflict analysis to a dichotomy of side 1 versus side 2. 3 Although such a dichotomy may help map how people see some parties in the system, the worksheet goes beyond this. That is, the analysis allows researchers or practitioners to identify the various parties involved in conflicts beyond those taking sides. Furthermore, to maintain simplicity, the worksheet does not directly detail larger systemic-level forces acting on the conflict situation, which could be addressed in discussion, such as the effects of new policies, laws, or environmental pressures imposed on a system. Hence, the worksheet should be used with complementary assessments and processes whenever possible to assess a given conflict.

To complete this basic version of the worksheet, a researcher or practitioner would ask participants (individually or in group discussions) to start at the top of the page and work their way down for each category of questions. 4 For example, participants would first respond to, “What’s the conflict about?” (box 1). Answers may also reveal the types of issues, interests, needs, procedural concerns, substantive disagreements, worldviews, psychological needs, and so forth that are involved in the conflict. Then participants would be asked to indicate which parties they perceive to be directly versus indirectly involved in side 1 of the conflict (boxes 2 and 4). Then perceptions about entities involved on the other side of the conflict would be assessed (boxes 3 and 5). Conceptually the upper part of the worksheet illustrates entities who are deeply involved in the network conflict. The lower part of the worksheet illustrates entities exclusively involved in more peripheral roles in the system, such as those who are observing or are neutral in the conflict but are not involved. 5 Once the information is collected individually or discussed in groups, researchers or practitioners can use the worksheet in various ways to learn about the system and then potentially to intervene.

Describing the System

Worksheet information can be beneficial in describing a variety of system characteristics. First, it can gauge the group’s overall level of confidence about the roles they perceive in the system. To calculate this, one would simply count the number of question marks in the worksheet or calculate the certainty ratio (i.e., [number of question marks/total number of entities in the system]−1). Second, researchers or practitioners could use information from the worksheet to measure the level of agreement, common ground, or disagreement between the parties about the nature of the conflict itself (box 1). If there are inconsistencies, practitioners could attempt to generate a clearer and more agreed-on understanding of the conflict among the parties or encourage the parties to appreciate how other views of the conflict could have legitimately formed in an effort to build more compassion and understanding in the system, akin to classic methods of conflict resolution (Deutsch, 1977; Pruitt and Kim, 2004).

Third, the worksheet approach could be used to explore interesting clues about dynamic network intelligence (DNI) in the network (Westaby, 2012). DNI represents how accurate people are in their perceptions about who plays what roles in the system. For example, if Jane on side 1 sees Joe as a direct actor on side 2 of the conflict (e.g., a goal preventer), but Joe sincerely does not place himself in that role at all, and instead views himself as an observer in box 8, such feedback to Jane may help alleviate her anger and system reactance toward Joe. In this case, Jane’s initial DNI was low, and this could be a significant psychological contributor to the conflict that is generating her negativity toward Joe. Moreover, if some people are placed in multiple boxes at the same time, they may be playing various sides of the conflict or are acting in ways perceived to be ambiguous by people monitoring the actions in the system. In a conflict situation where low DNI has been identified, the facilitators would ideally try to help members of the network navigate how perceptions are mapping onto reality (or not) in the social context, akin to how counselors apply principles in cognitive behavioral therapy.

Fourth, one can gauge a network hostility ratio in the system (the negators and reactors) by calculating the number of people who have checked names in side 1 and side 2 boxes divided by the total number of people named in those boxes. As this ratio approaches 1, it suggests an extremely contentious or escalated conflict, which would require a more urgent and directed intervention strategy. An implicit goal for those trying to resolve the conflict is to reduce this ratio so that anger does not transform into physical aggression. Finally, one can also gauge a conflict motivation ratio, which shows the overall balance of people motivated on side 1 versus side 2 of the conflict (the number of people in box 2 and 4 divided by total number of people in boxes 2, 3, 4, and 5). When this ratio approaches 1, it suggests that side 1 is dominating the network. When it approaches 0, it suggests that side 2 is dominating. When it is near .5, it suggests an even split of motivation on both sides. To gather this information, researchers or practitioners could create a network conflict scorecard to portray the variety of statistics in the broader system.

Transforming Roles

Another critical way that practitioners can use the network conflict worksheet is by examining how roles can be transformed. There are many ways this can happen. First, actors who are directly involved in the conflict are often interested in changing others themselves. For example, these parties may directly confront others in the system who are generating resistance. To illustrate, the primary actors for side 1 may directly confront the primary actors for side 2. These individuals will often use traditional techniques of negotiation, persuasion, incentives and disincentives, sanctions, and physical interventions to marshal their efforts (Pruitt and Kim, 2004).

However, there are many more dynamics that can occur in social networks when looking at the broader set of roles in the system. This network analysis approach assumes that an important underlying force for promoting conflict resolution in social networks comes from the power of resolution support. Resolution supporters (box 5) are individuals in a social network who are trying to help both sides of the conflict resolve their differences. A higher ratio of people in resolution supporter roles (the resolution supporter ratio) could serve as a force on the conflicting parties to stop or change their behavior. Mediators, leaders, or people simply interested in helping to stop the conflict would be found here. Instrumentally, resolution supporters may not only encourage the parties deep in the conflict to resolve their issues, they can also encourage people in peripheral roles to get involved as resolution supporters to help reduce the conflict. In all, this places a stronger cooperative force onto the conflicting parties and increases the likelihood that the parties may see the negative social consequences of their continued fighting.

Theoretically the lower middle portion of the worksheet represents a powerful location for motivating change in the broader system. This illustrates an important nonlinear orientation. That is, a practitioner may not want a network to simply move toward the peripheral part of the system as an approach to resolve all conflicts. This is because more social power in resolving conflicts is presumed to result from having more resolution supporters in a system than pure observers or interactants. Furthermore, moving entities to basic observer roles (box 8) may implicitly promote stonewalling behavior (“Just be quiet.”) or avoidant behavior, which can prevent issues from being sufficiently addressed, thereby increasing the potential for continued aggression when new triggering events occur. An important area for future research will be to examine the conditions under which a move to the observer box is more effective (e.g., When is taking time out more constructive or unconstructive in comparison to other options?).

Other interesting and unexpected processes can occur among those in peripheral roles. For example, on the one hand, resolution supporters (box 7) may be able to get some observers (box 8) to transform and join their efforts to help resolve the conflict, which would be constructive. On the other hand, resolution supporters may need to be more careful and mindful when trying to solicit support from important interactants in the system who were not aware of the conflict (box 9). Some of these interactants will understand the resolution supporters’ position and agree to join their efforts. In other cases, once interactants learn about the conflict, they may realize that they have their own vested interests and decide to join one of the sides, thereby escalating the conflict in the network. Alternatively, some interactants, after learning about the conflict, could become very upset with both sides of the conflict and enact the joint reactor role (box 6), which could do one of two things. When the conflicting parties learn that the previous interactant is angry at both sides, that could motivate them to cooperate, especially if that person is a powerful player in the system. Ironically, this would represent how the positivity of negativity can help resolve conflicts. However, this new joint reactor could cause the deeply entrenched parties to become angry toward the joint reactor, which may widen the level of hostility in the overall network. 6 Hence, resolution supporters need to be mindful of other people’s underlying motivations and reasons for their potential behavior when intervening in a network (Westaby, 2005). Finally, moving people from joint reactors to resolution supporters may also be a function of promoting empathy among the joint reactors so that they can understand how the parties may have ended up in the conflict. If empathy is generated, joint reactors may be more likely to transform into resolution supporters.

Other Applications and Caveats

The worksheet has the potential to introduce more complex ways to think about the social situation, which may start to reconfigure avenues for change in line with dynamical systems thinking (Vallacher et al., 2010). In problem-solving sessions, additional worksheets could also be generated around proposed solutions to the conflict to see whether everyone agrees on one side (i.e., a full agreement). Understanding the basic roles in network conflicts may help scholars and practitioners understand how large-scale interventions can be formed to reduce conflict, such as creating antibullying interventions in school systems. For example, this could be used to theoretically explain some of the work of Olweus, Limber, and Mihalic (1999), who developed a program for bullying prevention. Through dynamic network theory, their approach often targets the bully (e.g., side 1 actors who are goal striving to bully), the victim (e.g., side 2 goal preventers wanting the bullying to stop), as well as teachers, student peers, and school staff members in the network who are engaged in various other roles in the network, some of them dysfunctional. The network conflict worksheet would assist in clarifying the role behaviors that people are (or are not) implementing in the system to foster antibullying efforts.

As for caveats, one needs to be mindful of not too definitively labeling individuals in their roles. To counter this general human tendency, practitioners should highlight how it is common for people to change their roles over time or switch their roles quickly depending on the context. Also, although people may believe they are confident in their initial placement of individuals in the worksheet, there may still be unreliability in some systems. For example, a person may indicate that Juan is a primary actor for side 1 at time 1, but when asked again a day later, the person may fail to indicate Juan anywhere on the worksheet. Whenever possible, it is ideal to do multiple assessments over time to assess reliability. (See Westaby, 2012, for additional conflict resolution strategies and methodological issues.)

INTERNATIONAL LINKAGES

To widen our discussion, what about ways to promote sustainable world peace from a network perspective? The following was proposed as one example in dynamic network theory:

If entities across national borders can engage in joint network motivation linkages (i.e., G and S) toward collective goals that actually result in meaningful overall goal achievements, it will not only satisfy fundamental needs and desires across borders, but will also affect the network rippling of positive emotions that transcend national boundaries and promote goodwill between the nations from the ground up. Motivational and emotional bonds could then start stabilizing across borders. The delicate challenge in such initiatives is to build such linkages that at the same time do not overly interfere with each country’s desired state of sovereignty. (Westaby, 2012, p. 82)

Otherwise, some international linkages may be perceived as unwelcome advances that generate cultural conflicts and network resistance.

Several lines of research provide indirect support for these broad propositions. For example, using network methods on data compiled since World War II, Dorussen and Ward (2010) found support for the classic liberal argument that trade linkages between states reduce interstate conflict. In a study of what promotes international mediation linkages, Böhmelt (2009) found that states that had more indirect connections with other states as potential third parties increased the potential for mediation as compared to states that had only bilateral linkages during war. From a dynamic network theory perspective, this would increase the odds that observing states would change to resolution supporters of both sides, when needed, to help resolve conflicts. Dorussen and Ward (2008) also examined how intergovernmental organizations may promote peace. They found that state membership in these organizations increased network connections between states, which allowed organizational members to intervene in conflict resolution as individual members or as a collective. This illustrates the power of indirect resolution support as compared to direct diplomatic ties alone. However, Hafner-Burton and Montgomery (2006) caution that such international organizations and their disparate distribution of members can highlight power and prestige differences that may affect other conflict-related processes, such as in-group favoritism.

ONLINE DISPUTE RESOLUTION

The emerging field of online dispute resolution (ODR) is also relevant to conflict resolution. ODR represents a type of alternative dispute resolution that involves the use of e-mail, chat rooms, and other Internet-based media to facilitate communications between parties and their mediators or arbitrators (Hammond, 2003). Since the 1970s, negotiators have been using computers to organize negotiations, starting with platforms to organize data to today’s fully Web-based electronic negotiation systems (for a review, see Kersten and Lai, 2007). ODR has its advantages and disadvantages, and while some mediators believe that it provides an opportunity for reconciliation when face-to-face mediation is not possible or appropriate, others may believe that it should be avoided because written communication is more vulnerable to miscommunication (Raines, 2005). One study showed that negotiators in an e-mail condition, as compared to face-to-face negotiation, had more difficulty establishing rapport and trust, which contributed to poorer outcomes (Morris, Nadler, Kurtzberg, and Thompson, 2002). In a follow-up study, these researchers found that simply introducing a five-minute telephone call prior to commencing with e-negotiations had a significantly positive effect on outcomes by increasing rapport between negotiators. From a communication perspective, Brett et al. (2007) examined text from transcripts of online negotiations between buyers and sellers on the popular online auction site Ebay.com . They found that parties who phrased their arguments and complaints in such a way as to maintain the face of the other party had a positive effect on dispute resolution. Thus, online negotiators were served best by communicating concerns fairly and in a way that did not directly attack the other party.

CONCLUSION

Scholars and practitioners in the field of conflict resolution are acutely aware of the importance of capturing the complexity of social systems (Ricigliano, 2012). The approach taken in this chapter was to highlight how social network concepts can provide an additional approach to understanding the complexities of human conflict and its potential resolution. We illustrated how traditional social network concepts have been applied to a range of issues related to conflict, including some of the new dynamics observed in popular social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, which are changing the landscape of human interaction. This area will remain a hotbed of research as social media become even more common around the world. A major methodological limitation of this literature is that many of the empirical findings are based on cross-sectional designs with little experimental manipulation of variables.

We also illustrated how new concepts in dynamic network theorizing can provide a complementary approach to traditional network analyses by explicitly accounting for goals in networks. Including goals in networks not only provides a way to map how people are working with or against one another in a network; it may provide a more refined analysis about the level of positivity and negativity in relation to goal conflicts. Future research is needed to examine these contrasts because it is imperative for scholars and practitioners to have an accurate understanding of overall system dynamics in efforts to structure effective interventions. Although social network concepts are providing a useful way to portray social relations and human conflict, much more rigorous research is needed to fully appreciate this potential.

Notes

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50 (2), 179–211.

Bargh, J. A., & McKenna, K.Y.A. (2004). The Internet and social life. Annual Review of Psychology, 55 , 573–590.

Balkundi, P., Barsness, Z., & Michael, J. H. (2009). Unlocking the influence of leadership network structures on team conflict and viability. Small Group Research, 40 , 301–322.

Balkundi, P., & Kilduff, M. (2006). The ties that lead: A social network approach to leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 17 , 419–439.

Böhmelt, T. (2009). International mediation and social networks: The importance of indirect ties. International Interactions, 35 , 298–319.

Brenner, G. F., Norvell, N. K., & Limacher, M. (1989). Supportive and problematic social interactions: A social network analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 17 , 831–836.

Brett, J. M., Olekalns, M., Friedman, R., Goates, N., Anderson, C., & Lisco, C. C. (2007). Sticks and stones: Language, face, and online dispute resolution. Academy of Management Journal, 50 , 85–99.

Burt, R. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2006). Short-term and long-term effects of violent media on aggression in children and adults. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 160 , 348–352.

Cartwright, D., & Harary, F. (1956). Structural balance: A generalization of Heider’s theory. Psychological Review, 63 , 277–293.

Chaulk, K., & Jones, T. (2011). Online obsessive relational intrusion: Further concerns about Facebook. Journal of Family Violence, 26 , 245–254.

Coleman, P. T. (2011). The five percent: Finding solutions to (seemingly) impossible conflicts . New York: Public Affairs, Perseus Books.

Curşeu, P. L., Janssen, S.E.A., & Raab, J. (2011). Connecting the dots: Social network structure, conflict, and group cognitive complexity. Higher Education, 63 , 621–629.

de Dreu, C.K.W., & Gelfand, M. J. (2008). Conflict in the workplace: Sources, functions, and dynamics across multiple levels of analysis. In C.K.W. de Dreu & M. J. Gelfand (Eds.), The psychology of conflict and conflict management in organizations (pp. 3–54). New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Deutsch, M. (1977). Recurrent themes in the study of social conflict. Journal of Social Issues, 33 , 222–225.

Dorussen, H., & Ward, H. (2008). Intergovernmental organizations and the Kantian peace: A network perspective. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52 , 189–212.

Dorussen, H., & Ward, H. (2010). Trade networks and the Kantian peace. Journal of Peace Research, 47 , 29–42.

Facebook. (2012). Key facts . Retrieved September 28, 2012 from http://newsroom.fb.com/content/default.aspx?NewsAreaId=22

Ferguson, C. J. (2010). Blazing angels or resident evil? Can violent video games be a force for good? Review of General Psychology, 14 , 68–81.

Finch, J. F., Okun, M., Barrera, M., Zautra, J., & Reich, J. W. (1989). Positive and negative social ties among older adults: Measurement models and the prediction of psychological distress and well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology, 17 , 585–605.

Friedman, R., & Currall, S. C. (2003). Conflict escalation: Dispute exacerbating elements of e-mail communication. Human Relations, 56 , 1325–1347.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63 , 221–233.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78 , 1360–1380.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., & Montgomery, A. H. (2006). Power positions: International organizations, social networks, and conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 50 , 3–27.

Hammond, A. G. (2003). How do you write “Yes”? A study on the effectiveness of online dispute resolution. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 20 , 261–286.

Herrera, L. (2012). Youth and citizenship in the digital age: A view from Egypt. Harvard Educational Review, 82 , 333–438.

Hughes, D. J., Rowe, M., Batey, M., & Lee, A. (2012). A tale of two sites: Twitter vs. Facebook and the personality predictors of social media usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 , 561–569.

Hundley, H. O., & Anderson, R. H. (1995). Emerging challenge: Security and safety in cyberspace. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 14 , 19–28.

Jehn, K. A. (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40 , 256–282.

Kersten, G. E., & Lai, H. (2007). Negotiation support and e-negotiation systems: An overview. Group Decision and Negotiation, 16 , 553–586.

Kiesler, S., Siegel, J., & McGuire, T. W. (1984). Social psychological aspects of computer-mediated communication. American Psychologist, 39 , 1123–1134.

Kilduff, M., & Tsai, W. (2003). Social networks and organizations . London, UK: Sage.

Knoke, D. & Yang, S. (2007). Social network analysis: Quantitative applications in the social sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Krackhardt, D., & Stern, R. N. (1988). Informal networks and organizational crises: An experimental simulation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51 , 123–140.

Kupersmidt, J. B., Griesler, P. C., DeRosier, M. E., Patterson, C. J., & Davis, P. W. (1995). Childhood aggression and peer relations in the context of family and neighborhood factors. Child Development, 66 , 360–375.

Labianca, G., Brass, D. J., & Gray, B. (1998). Social networks and perceptions of intergroup conflict: The role of negative relationships and third parties. Academy of Management Journal, 41 , 55–67.

Lee, H. (2005). Behavioral strategies for dealing with flaming in an online forum. Sociological Quarterly, 46 , 385–403.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science . New York: Harper & Brothers.

Lyndon, A., Bonds-Raacke, J., & Cratty, A. D. (2011). College students’ Facebook stalking of ex-partners. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14 , 711–716.

Lysenko, V. V., & Desouza, K. C. (2012). Moldova’s Internet revolution: Analyzing the role of technologies in various phases of the confrontation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79 , 341–361.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27 , 415–444.

Mesch, G. S. (2009). Parental mediation, online activities, and cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 12 , 387–393.

Moor, P. J., Heuvelman, A., & Verleur, R. (2010). Flaming on YouTube. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 , 1536–1546.

Morris, M., Nadler, J., Kurtzberg, T., & Thompson, L. (2002). Schmooze or lose: Social friction and lubrication in e-mail negotiations. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6 , 89–100.

Mouttapa, M., Valente, T., Gallaher, P., Rohrbach, L. A., & Unger, J. B. (2004). Social network predictors of bullying and victimization. Adolescence, 39 , 315–335.

Muise, A., Christofides, E., & Desmarais, S. (2009). More information than you ever wanted: Does Facebook bring out the green-eyed monster of jealousy? Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 12 , 441–444.

Neal, J. W. (2009). Network ties and mean lies: A relational approach to relational aggression. Journal of Community Psychology, 37 , 737–753.

Newman, M.E.J. (2003). The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM Review, 45 , 167–256.

Olweus, D., Limber, S., & Mihalic, S. F. (1999). Blueprints for violence prevention, book nine: Bullying prevention program . Boulder, CO: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence.

Papp, L. M., Danielewicz, J., & Cayemberg, C. (2012). “Are we Facebook official?” Implications of dating partners’ Facebook use and profiles for intimate relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15 , 85–90.

Pruitt, D. G., & Kim, S. H. (2004). Social conflict: Escalation, stalemate, and settlement (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Raines, S. S. (2005). Can online mediation be transformative? Tales from the front. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 22 , 437–451.

Ricigliano, R. (2012). Making peace last: A toolbox for sustainable peacebuilding . Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Turnage, A. K. (2007). Email flaming behaviors and organizational conflict. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13 , 43–59.

Vallacher, R. R., Coleman, P. T., Nowak, A., & Bui-Wrzosinska, L. (2010). Rethinking intractable conflict: The perspective of dynamical systems. American Psychologist, 65 , 262–278.

Vanbrabant, K., Kuppens, P., Braeken, J., Demaerschalk, E., Boeren, A., & Tuerlinckx, F. (2012). A relationship between verbal aggression and personal network size. Social Networks, 34 , 164–170.

Walen, H. R., & Lachman, M. E. (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17 , 5–30.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications (Vol. 8). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Watts, D. J. (2004). The “new” science of networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 30 , 243–270.

Westaby, J. D. (2005). Behavioral reasoning theory: Identifying new linkages underlying intentions and behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 98 , 97–120.

Westaby, J. D. (2012). Dynamic network theory: How social networks influence goal pursuit . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Westaby, J. D., Probst, T. M., & Lee, B. C. (2010). Leadership decision-making: A behavioral reasoning theory analysis. Leadership Quarterly, 21 , 481–495.

Xia, L., Yuan, Y. C., & Gay, G. (2009). Exploring negative group dynamics: Adversarial network, personality, and performance in project groups. Management Communication Quarterly, 23 , 32–62.

Yilmaz, H. (2011). Cyberbullying in Turkish middle schools: An exploratory study. School Psychology International, 32 , 645–654.

Zeitzoff, T. (2011). Using social media to measure conflict dynamics: An application to the 2008–2009 Gaza conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55 , 938–969.