10

BOB HUGGINS ERA (1989-2005)

THERE’S A NEW SHERIFF IN TOWN

The new coach called a 3 p.m. meeting with his players. It was held in Laurence Hall because the new basketball office in Shoemaker Center wasn’t ready.

Bob Huggins waited while some guys sauntered in around 3:15. Others strolled in at 3:30.

“Then he just went off,” Keith Starks said.

The Bearcats were not just introduced to their new leader, they were treated to a display of, uh, colorful language and verbal assaults the likes of which they were unaccustomed to.

“If this is how you think it’s going to be, pack up your stuff and go back to where you came from,” Huggins shouted. “I will win with walk-ons.”

It was April 1989.

“You can’t run a business that way,” Huggins recalled, almost 15 years later. “You can’t have people sitting around waiting for other people to show up. We start meetings on time. We start practices on time. We leave on time. It could’ve been the first day, it could’ve been the 10th day, the message wasn’t going to change: Be where you’re supposed to be.”

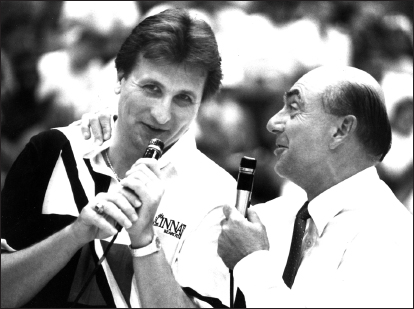

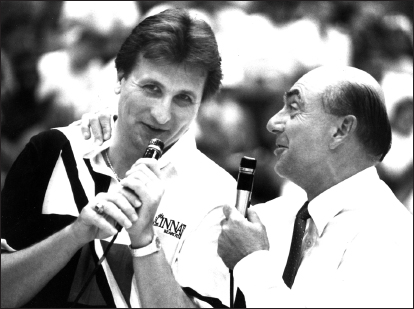

A 37-year-old Bob Huggins (left) and Dick Vitale take part in the show during UC’s Midnight Madness festivities in October 1990. (Photo by David Baxter/University of Cincinnati)

He wasn’t just talking about basketball; he was talking about life.

Some guys took him seriously, some guys didn’t.

Lou Banks and Elnardo Givens didn’t. Banks eventually came around; Givens, UC’s only point guard and the team MVP the previous season, didn’t. He was kicked off the team in September 1989 for missing classes.

“That got everyone’s attention,” Starks said. He told teammates: “This guy’s for real. He’s not going to take any crap from anybody.”

The players didn’t exactly go out of their way to see Huggins that summer. Quite simply, some were a little afraid.

Huggins asked players what were the problems with the program. Of all things, they mentioned the old uniforms and mismatched warmups. “That was easy to fix,” Huggins said. He asked them to design new uniforms. He ordered new practice gear. He wanted a fresh start. UC had not been to the NCAA Tournament since 1977—12 long years.

Starks, Banks, Levertis Robinson and Andre Tate were the only returning scholarship players. Michael Joiner and Tarrice Gibson, Huggins’s first high school recruits, were freshmen.

“Our first day of practice was hell,” Starks said. “We had never practiced that hard, ever. Guys were throwing up, falling down.

“This is what you have to do to win,” Huggins told them.

“We had heard certain stories about Coach Huggins,” Robinson said. “We had heard he was tough, which is true, but the toughness was not as it was categorized. He was a very level-headed coach and he was passionate about the game. He pretty much let us be young men. The enthusiasm that he had is what really set the tone for me.”

“He honestly believed we could win a national championship his first year there,” Starks said. “And he made us believe it.”

HE SAID IT AND HE MEANT IT

Huggins did believe UC could win a national championship. “If I didn’t, I don’t know who would,” he said.

And he wasn’t afraid to let the world know what he expected. In the press conference when he was introduced as UC’s new coach, Huggins made it clear that his goals were annual Final Four appearances and an NCAA title.

“We want to win right now,” he said the day his hiring was announced. “I don’t want to cheat people. If you say you’re on a five-year plan, you’re basically asking for an excuse to lose.”

He never regretted setting the bar so high.

“That’s what you play for,” Huggins said. “I thought coming in here the Metro (Conference) was a great league. At that time it was. Louisville had won a national championship (in 1986). If you could get to the top of the league and compete with Louisville, you should be able to compete on a national level.

“Some coaching friends said, ‘You shouldn’t say things like that, people will expect it. Guys get fired for saying things like that.’

“I think the biggest thing we had to change was the work ethic. They didn’t really have a strength program, so to speak. They just didn’t put the time in for whatever reason. The guys who were here, I thought, were really good. I loved coaching them. There just weren’t many of them.”

Didn’t matter.

UC upset 20th-ranked Minnesota 66-64 in Huggins’s first game and went on to a 20-14 season, including a 1990 National Invitation Tournament bid. In Huggins’s third season, Cincinnati was back in the Final Four, just as he had predicted.

LAST-SECOND LOU

He had a broken bone in his left hand. He missed practice the day before the game because he went to see a doctor.

Junior Lou Banks’s response was to go out and have a career night against Dayton on December 17, 1989. He scored 31 points, added seven rebounds and made the game-winning shot with two seconds remaining in a 90-88 victory.

“I wasn’t so much in pain that night,” Banks said. “They had it taped up pretty good. I hit it a couple times, but it wasn’t throbbing pain.

“That was one of the first times I had a great game in Shoemaker. All my other good games came on other courts.”

Banks came to UC’s rescue several times during the 1989-90 season. In addition to the Flyers, he had last-second shots to beat Florida State and Creighton, and he made two free throws against DePaul to send that game into overtime.

“I was the captain,” he said. “It was my team, so I wanted the ball at the critical times and they wanted to give it to me.”

His best game probably came his senior year, when the Bearcats upset No. 11 Southern Mississippi 86-72 at Shoemaker Center. Banks finished with 23 points, nine rebounds and a career-high nine assists. He had averaged just 11.7 points in the previous nine games.

IN FOR THE LONG HAUL

Tarrice Gibson was not the first player to sign with UC after Huggins became coach; that was Michael Joiner (May 1989). But Gibson, who signed a month after Joiner, was Huggins’s first four-year player.

Gibson is from Dothan, Alabama, in the southeast corner of the state (population 60,000). Dothan is known as the “Peanut Capital of the World.” Gibson really wanted to go to Georgetown—a basketball power in the 1980s under coach John Thompson—but the Hoyas instead signed another guard. Gibson felt that other schools backed off him because they thought he was headed to Georgetown.

Florida State offered him a chance to walk on. But Gibson verbally committed to Howard Community College in Big Spring, Texas.

Cincinnati entered the picture late in Gibson’s senior year, 1989. His recruiting trip to Cincinnati was his first airplane ride, and assistant coach John Loyer and Keith Starks met Gibson at the airport.

“As soon as I met Keith, Lou (Banks), and Andre (Tate), I was sold,” Gibson said. “The first time I saw Lou, he said, ‘We’ve got to put some muscles on you, little fella.’ They called me ’Bama. I went back home, and a week later I signed.”

The Howard coaches told him: If you have the chance to play at UC, go for it.

“What Lou, Andre, Keith and Levertis (Robinson) did in 1989 was the best thing that ever could’ve happened to me,” Gibson said. “You’ve got Lou the hardass, Andre the consummate professional, Levertis the minister of defense, and Keith the workhorse. They taught me everything they knew. Andre’s leadership, Lou’s tenacity, Keith’s will not to give up. Levertis was mild tempered; nothing ever rattled Levertis.

“They laid the foundation for the family.”

FAMILY MATTERS

Gibson arrived in Cincinnati with some clothes in a brown paper bag on September 16, 1989. He remembers the date. He owned next to nothing.

Loyer picked him up at the airport and dropped him off on campus. Tate was going to his mailbox in the dorm. “’Dre, I’ve got your new teammate right here,” Loyer said. “Take care of him.”

Tate and a female friend took Gibson to K-Mart and bought him sheets, a pillow and blanket. Banks took him to a bank and gave him $10 to open an account. “I didn’t have a dime to my name,” Gibson said.

All of this is why, 25 years after he came to town, Gibson lives in Cincinnati, keeps in touch with numerous former players from the Huggins era and offers advice to new players who need it.

“That’s what we do as a family, we try to go above and beyond the call of duty for each other,” Gibson said. “I talk to every teammate that I had at the University of Cincinnati more than I talk to my biological brother and sisters. My four years at UC were the best years of my entire life.”

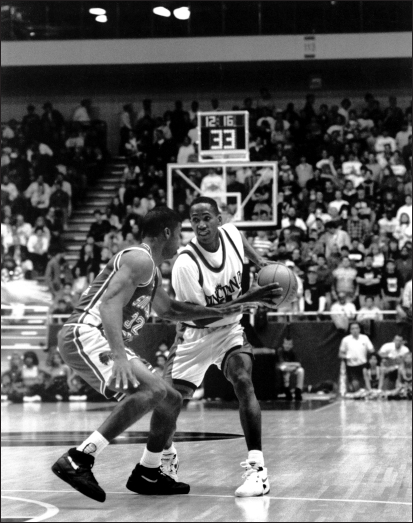

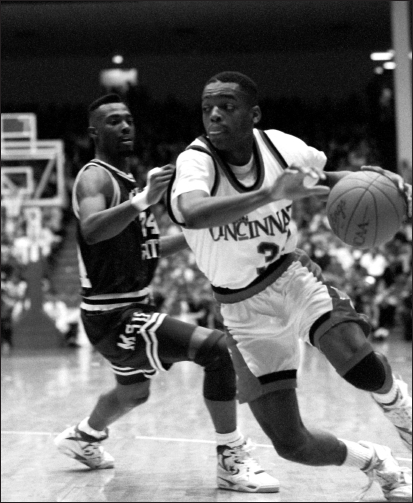

Tarrice Gibson brought tremendous energy and aggressive play off the bench as the Bearcats’ top reserve during the team’s run to the 1992 NCAA Final Four. Gibson currently ranks eighth at UC with 150 career steals. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

UC fans probably know Gibson by the name “Tarrance”—which he insists is not his name. He should know, right?

Gibson said a guidance counselor from Northview High School misspelled his name on a form that went to UC. Then UC referred to him as Tarrance in all publications for the next four years.

“It never bothered me,” he said. “I thought it was cool that they were renaming me. But it bothered my grandma. I went to (sports information director) Tom Hathaway once and told him, ‘That’s not the spelling and my grandma doesn’t like it.’ Tom told me that I needed to bring my birth certificate to show him the spelling of my name. I thought, you think I’m going to lie about my name? I said, ‘Forget it.’”

To be fair, Gibson signed his name as “Tarrance,” was referred to that way by almost everyone and never complained to UC officials until just before his senior season—too late to make changes in various publications. He finds the confusion somewhat amusing.

Now, he said, he signs all business papers “Tarrice.” He is known in Cincinnati by Tarrance, Tarrice and T-Rat, his nickname. “I answer to every one of them,” he said.

BREAKTHROUGH RECRUIT

Perhaps the most important recruit in the Huggins’s era was Herb Jones, a two-time junior college All-American at Butler County (Kansas) Community College.

“He was a great player,” Huggins said. “I thought what we had to do was win, and I thought Herbert was probably the best guy out there that we could get to win.”

UC was the first school trying hard to sign him, and that was important to Jones. When Oklahoma coach Billy Tubbs made a late run for Jones, showing him Final Four and conference championship rings, Jones remained loyal to Cincinnati.

“Huggs came out (to Kansas) and was showing me the system,” Jones said. “I thought I’d fit in. I don’t really know how I was sold. All my friends were saying, ‘Why do you want to go to Cincinnati? You can go anywhere.’”

The six-foot-four Jones was relatively quiet. He stayed to himself at first more than he hung out with teammates. He mostly went to class, practice and the cafeteria. But on the court, it didn’t take long for him to make an impression.

“Herb was the real deal,” Starks said. “No one could stop him. Nobody was as strong as him on the block. He was quick off the floor. We always thought Levertis could jump high. They had classic battles. If Herb was 6-10, he would’ve been (national) player of the year (in 1992).”

“I had never seen anybody that small be able to play down low the way he did and score in all kinds of ways,” Anthony Buford said. “There’s no question he didn’t get his due nationally. I think he got his due on our team.”

And within the program.

UC coaches would use the fact that they signed the National Junior College Player of the Year to help land more top junior college players in the next recruiting class.

“If you would ask Huggs: ‘Who’s the guy who turned the program around?’ He’d tell you Herb,” former assistant coach Steve Moeller said. “He was the first high-profile guy.”

“I didn’t really think of it like that at that time,” Jones said, “but that’s what people said later, that I broke the recruiting barrier.”

Jones was an Associated Press honorable mention All-American in 1992. UC’s previous AP honorable mention All-American was Robert Miller in 1978.

CHANGE OF ADDRESS

Following Anthony Buford’s second season at the University of Akron, his coach, Bob Huggins, accepted the head coaching position at the University of Cincinnati. After Huggins took the job, he returned to Akron to meet with each player. Right away, Buford wanted to know whether there was a spot for him at UC.

“He was who I trusted,” Buford said. “The only reason I went to play basketball at Akron was because of Bob Huggins.”

Privately, Huggins told people he wanted Buford with him in Cincinnati. But he didn’t want it to appear as if he was raiding the Akron program. He encouraged Buford to stay put, saying he didn’t know what the situation at UC would be like. Buford was on pace to become Akron’s No. 2 all-time scorer; he would have 1,400 points after three seasons.

The players lobbied for assistant coach Steve Moeller, who ended up joining Huggins at UC, to get the Akron job. But instead the school chose Coleman Crawford, who had worked under Huggins, then spent a year as an assistant at Tennessee.

Suffice it to say, Buford did not get along with Crawford for a variety of reasons. Buford would tell Huggins how unhappy he was, but Huggins couldn’t say anything in response. When his junior season ended, Buford told Huggins: “I’m not playing my senior year at Akron. I am transferring down there (to UC) whether you like it or not.”

Every award Buford earned from his last season at Akron he threw in the trash.

Akron’s spring classes ended in May. Buford headed right for Cincinnati. He would have to sit out one year, then would have only one season of eligibility to play for the Bearcats.

That was fine with him.

THE EXAMPLE

Buford had surgery on his right knee in late March 1990, after Akron’s season ended. When he arrived in Cincinnati two months later, he could only walk around. No running. No basketball.

His first day on campus, he met some of the players for the first time. Tate, who had just completed his college career, immediately said, “Let’s play one on one.”

“I can’t,” Buford said.

But as soon as he did start working out and playing pick-up games, the holdover Bearcats began testing the new guy.

“I finally realized what was going on,” Buford said. “When he first came to UC, all Huggs talked about was how tough his former players were. He used me a whole lot as an example. So these guys had heard a lot about me, and now here I am in the flesh and they all wanted to find out firsthand. They were going at me like you can’t imagine.

“I’m kind of in the mindset that I’ve played three years of college basketball and I don’t have to prove anything to anybody. And I know physically I’m not ready. But they did not like me. You could hear them on the side, saying, ‘He ain’t all that. Huggs is full of it.’”

Tate, Robinson and Starks—all recruited to UC by Tony Yates—were the main culprits.

“When Buford got there, everybody did want a piece of him,” Tate said. “Huggs had built him up to be a tough guy. We had heard so much about him. And we didn’t back down from anybody.”

“We were a very tight group,” Robinson said. “Buford was kind of like an outsider.”

Finally, one day, Buford served notice: “Do what you need to do right now because this doesn’t mean anything. When the season starts and I’m healthy, I’m going to kill all of you.”

The response: Yeah, whatever.

Buford knew Huggins’s offense better than anyone on the team. Tate, a graduate assistant that season, also knew the offense well and practiced sometimes with the Bearcats. Together, they posed problems for the starters.

It wasn’t until later that Buford would become friendly with some of the players.

He even got into fights with Robinson during practice. One day, while going for a loose ball, Buford caught Robinson with an elbow. Robinson, a second-degree black belt in Tae Kwon Do, responded with a quick punch to Buford’s jaw.

“I started to retaliate, then I realized who it was,” Buford said. “Being a little bit smart, I decided not to take it any further.”

“That’s what happens in the heat of battle,” Robinson said. “The way our practices went, you couldn’t expect anything but that.”

THE CALIFORNIA KIDS

Southern California, 1990.

“I didn’t know anything about Cincinnati,” Corie Blount said. “I didn’t even know they had a basketball program.”

“All I knew was WKRP,” Terry Nelson said. “I didn’t even know Oscar Robertson went here.”

“I knew about the Big O, but that was a long time ago,” Erik Martin said. “I knew Cincinnati didn’t do anything in the last decade that would jog my memory.”

Such was the mindset of three junior-college recruits being pursued by the University of Cincinnati.

The main targets were Nelson from Long Beach College and Blount from Rancho Santiago. Moeller had recruited the state of California as an assistant at Rice and Texas earlier in his career. In July 1990, he went to the West Coast to see Nelson and Blount.

It was during that trip, at a summer-league game at Cerritos College, that Nelson had what is probably the best game of his life. “I was like 16 of 17 from the field,” Nelson said. “I scored 34 points, had a couple dunks. Moe went back and told Huggs: ‘This guy’s a player. He can score, he’s tough, he can rebound and he can defend.’”

It was also during that trip, at an open gym at Rancho Santiago, that coach Dana Pagett told Moeller: “I’ve got a guy who’s better than Corie.” The player was Erik Martin, who had left TCU after the 1989-90 season and was to play for Rancho Santiago.

Moeller recruited all three. Junior college players typically didn’t sign letters of intent until the spring, but the Cincinnati coaches—in just their second year in Clifton—wanted to secure these three in November.

Nelson and Blount, who knew each other from summertime games, took their recruiting visits together in October. Nelson, who had signed with Cal State-Fullerton out of high school, wanted to leave California. He was the easiest to sell.

“I told Corie the first night in Cincinnati I was coming,” Nelson said. “I said I know what I want. If you come, we’ve got a chance to go to the Final Four. I just liked the chemistry of the guys. We had a good time. I fell in love. I knew this was a place I could settle down and do some fishing. I told Huggs the next day. I don’t think he took me seriously.”

Blount still wanted to take a trip to Tennessee. He was also considering UNLV and Utah.

After Nelson and Blount returned from UC with good reports, Martin decided he wanted to take a visit to Cincinnati, too. However, he did not want to sign until the spring. His father Edward even told the UC coaches that.

Well, Huggins responded, then Erik has eliminated himself because we need commitments now. Moeller repeated that message to the family.

Eventually, Martin’s father called to say his son had changed his mind. Sorry, Huggins said. “The only way I’ll bring him in on an official visit is if he comes in here and likes it, he signs without going anywhere else.”

Which, of course, is what happened. Then Martin went to work on Blount. “Just imagine, the three of us can go there and turn it around,” he’d say.

Blount took a recruiting trip to Utah. Finally, he, too, committed to the Bearcats.

“I told all my friends I was going to Cincinnati with Erik and Terry,” Blount said. “My friends didn’t even know where Cincinnati was. They were saying, ‘That ain’t no basketball school.’”

The three California Kids signed in November 1990.

They came to Cincinnati together the following summer, driving in a rented Plymouth Sundance. It took them four days to cross the country.

“We were the California Connection,” Blount said. “We felt the hype when we started playing in the summer league (at Purcell Marian High School). Then Nick (Van Exel) came later. . . . It took off from there.”

SETTING A TONE

Early in the summer of ’91, some Bearcats played pick-up games at Shoemaker Center—and some did not. Herb Jones played over at Xavier. Some guys rarely played at all.

Huggins returned from a trip out of town and heard all this. He summoned the team to a racquetball court on Shoemaker Center’s lower level, then turned out the lights.

He proceeded to blast each and every player, including Buford.

Said Blount: “I’m looking at Erik and he’s looking at me, like, man, it’s true what they say, this dude is crazy. That did it. We were playing together in the gym all the time after that.”

It was during that meeting, Nelson said, that he told everyone he thought his junior college team was successful because the players did everything together.

“If we went to the store, we went together,” Nelson said. “Our motto was togetherness. They looked at me like I was crazy and started laughing and making jokes out of it. They thought it was funny, but it soon became our theme. Everything we did from that point, we did together.”

“COACH” BUFORD

Herb Jones, Tarrice Gibson, Allen Jackson and Anthony Buford were already in town. Nick Van Exel arrived from Trinity Valley Junior College in Texas. The California Kids—Corie Blount, Terry Nelson and Erik Martin—came from the West Coast.

This collection of players from all over the country started bonding months before the magical 1991-92 season was to start.

Buford watched the talent and felt, if the chemistry was right, if everyone was “on the same page,” if the guys could handle Huggins, there was potential for something special.

So he started coaching. He’d warn his teammates old and new about what they would experience with Huggins, how at times he’d be uptight, how there were times the players would not be able to do anything right. “He’s going to cuss you out and say crazy things,” Buford said. “Don’t pay attention to how it’s being delivered, just listen to the message.”

Buford would gather guys in his apartment and ball up pieces of paper and try to explain the offenses, the defensive presses. Whatever he could show them about Huggins’s system, he did.

“Our group trusted each other,” Nelson said. “When Anthony said something to me, I didn’t get defensive thinking that he was trying to coach me. I just thought he was helping me. I figured whatever he could teach me would get me to play sooner. Everybody wanted to win.”

There was tremendous basketball IQ among the group. They really understood the game. By the time preseason practices started, the coaches were able to move through plays quicker and work on more advanced offenses and defenses.

“They were ahead,” Huggins said. “I don’t know how much ahead. The important thing is we had guys that were leading and guys that were helping. I think their understanding of what was supposed to happen was a lot better.”

SHORT RESISTENCE

Blount did not want to lift weights when he got to UC, and he did anything he could to get out of it. “You recruited me to play basketball, you didn’t recruit me to be a body builder,” he would tell Huggins.

After he missed a few weightlifting sessions, there was a knock on his apartment door at 4:30 a.m. It was Huggins.

“Get your ass up,” he said.

He took Blount to the Armory Fieldhouse and had him running. Several miles.

“I did that about three times,” Blount recalled, “and then I said, ‘All right, I’m going to start lifting.’”

STARTING OFF WITH A THUD

Not many Division I teams lose preseason exhibition games. But that’s what happened to kick off the 1991-92 season.

Athletes in Action 82, UC 79.

’Nuf said.

The Bearcats blew a 20-point first-half lead, which prompted Huggins to tell the media afterward: “If I were playing miniature golf with my mother, I’d want to bury her. You can’t stop. You’ve got to keep playing. . . . We’re not very good right now. But we will be good. This is a great lesson for us.”

After listening to a Huggins tirade in the locker room for a half hour after the game, many of the players stayed put for another two or three hours. It was that night the Bearcats put their team goals in writing:

• Work hard every day in practice

• Leave the attitude at the door

• Finish 23-4

• Win the Great Midwest Conference regular-season title

• Win the GMC tournament title

• Go to the Elite Eight of the NCAA Tournament

This was a program that had not gone to the NCAA Tournament in 15 years.

HIT ME WITH YOUR BEST SHOT

Before Martin begins, he cautions: “Huggs is going to try to change the way this story goes.”

Now you know it’s going to be good.

It was early in the 1991-92 season, and—this is important to know—Martin felt he was in Huggins’s doghouse. So naturally, he was mad at Huggins, too.

The first official practice, Martin knew he wasn’t in the best shape. Still, he felt everyone was struggling. But when Huggins called the players in for a huddle, he got all over Martin. “He pretty much cursed me out for about five minutes. I had a real bad practice that day. Everything was new as far as drills and all that. I kept thinking, why is he picking on me? Corie and Nick didn’t have a great practice, either. It wasn’t so much that he was singling me out, but he felt like I had more in me than I was giving that day.”

During practice another day, a Bearcat drove for a layup and the defender didn’t bother to take a charge. That, of course, enraged Huggins.

“That’s it,” the coach shouted. “We’re going to do the charge drill. I’m going to take the charge. Now who wants to go first?”

Martin was prepared to flatten any teammate who did not let him get to the front of the line. “I was going first,” Martin said. “I was going to run over Huggs.”

He took one dribble. Two dribbles. Then Martin picked up the ball, put his head down and started running at Huggins “like a football player.”

“And Huggs turns,” Martin said with a grin. “He takes the charge, but he’ll swear to this day he stood in there. He turned his body, man. He knew I was going to plow through him. I knocked him down, ripped his pants a little. Then he got up and said, ‘That’s the way you take a charge. Now go shoot free throws.’ He stopped the drill right there. At first, he was going to take a charge on everyone on the team. After he got up, he went and talked to the trainer.”

“He thinks that’s really funny,” Huggins said. Then turning serious, he added, “But I think that’s good. Then they understand that I’ve never asked them to do anything I would not do.”

HIGHS AND LOWS

If Michigan State had recruited Buford out of Flint (Michigan) Central High School, he would’ve seriously considered joining the Spartans. But Buford heard that then-coach Jud Heathcote told people he was too small.

So when it was time for the Bearcats to play at Michigan State on December 21, 1991, Buford was “all jacked up.” Close to 20 friends and family members were in the stands. The Spartans were ranked No. 12 in the nation. Both teams were unbeaten. “Don’t hurt us too bad,” Heathcote said to Buford before the game.

“He really had no idea what was coming,” Buford said. “I was hot when I stepped off the plane, and it never stopped.”

It was the eighth game of Buford’s UC career, and it was one of his best. He scored 29 points on eight-of-14 shooting. The Bearcats were ahead by 18 with 12:30 remaining.

Everything was going so well. Until the end.

UC led by just two points in the final seconds. Buford ran to double-team one of the Spartans and left his man wide open. The pass went to MSU reserve guard Kris Weshinskey in the corner, and he nailed a three-pointer with 4.6 seconds left. “That mistake probably cost us the game,” Buford said.

The Bearcats had one final possession. Buford had the ball, got inside the foul line, a mere 12 feet from the basket, launched the kind of jump shot he had practiced all the time in high school and . . . the ball hit the rim and bounced away.

Michigan State 90, UC 89.

“We got exactly the shot we wanted,” Huggins said afterward.

“I went through a range of emotions,” Buford said. “I felt so good at the beginning of the game and so bad at the end.”

It was after that game that Huggins took off his Rolex watch and hurled it at a blackboard in the locker room, breaking the blackboard and watch. Little diamonds fell onto the floor. Nobody moved, then he said: “I hope you all have a miserable Christmas.”

WHO’S GOT MY BACK?

After two days off, the team returned for a Christmas Day practice that lasted five hours.

A few days later, during another intense practice, Huggins got upset with Gibson and told him to get off the court.

“No,” Gibson said. “This is my team.”

He gave the ball to A.D. Jackson and told him to start running a play. “A.D., pick up the ball,” Huggins said. “Tarrance, get off the floor.”

Gibson wouldn’t leave. Huggins was getting angrier. Jackson didn’t know what to do. Martin whispered to Blount: “If he gets into it with Tarrance, we’re going to jump him.”

“We weren’t really going to do it, but we were getting our nerve up to say something to him,” Blount said.

“C’mon A.D., let’s go,” Gibson yelled.

“OK, I’m going to say it one more time,” Huggins shouted, “If Tarrance doesn’t get off the floor, we’re going to put the balls away and we’re going to run for the next three hours.”

Herb Jones looked at Huggins, then at Gibson. “Tarrance, you’ve got to get off the floor, man! You’ve got to go.”

“We weren’t about to run for anybody,” Blount said.

Gibson left the court, and the players started laughing.

QUICK EXIT

Nelson felt like he had some good practices leading up to UC’s January 8 game at Tennessee, whose star player was Allan Houston. Early in the game, Nelson told some teammates: “I can feel it; I’m going to have a great game today.” He was thinking four or five charges, seven or eight rebounds.

Huggins called his name, and Nelson jumped off the bench and pulled off his warmups. He always wore elbow pads, which were pulled down when he was on the bench. Nelson was going to inbound the ball and figured he’d do that, then pull up his elbow pads.

Well, his teammate took the pass and threw the ball right back to him. The Tennessee defender was hand-checking Nelson, pushing at his hip, and Nelson’s foot moved. He was called for traveling.

Huggins immediately yanked Nelson after a three-second appearance.

“I didn’t even have time to pull my elbow pad up,” Nelson said. “Corie was coming to get me and he’s cracking up laughing. That’s all I played the whole game.”

His name didn’t even show up in the official box score in the newspaper the next day.

THE GUARANTEE

UC had just beaten Alabama-Birmingham 76-52 on January 25, 1992, at Shoemaker Center, and Nelson was in the hallway outside the media room with former Cincinnati Post reporter Bill Koch, who was asking about the Bearcats’ next game—against Xavier.

“How do you think you guys are going to do in the Crosstown Shootout?” Koch asked.

“Xavier doesn’t have a chance,” Nelson said. “We should blow them out.”

The next day, Nelson’s phone started ringing around 7:30 a.m. A few radio stations wanted him to do live interviews. He was half asleep, answering questions about Xavier and making jokes. He loved the attention.

Of course, he had not seen a newspaper yet.

The phone rang again. Nelson was thinking it was another interview request.

“Get your ass in my office in five minutes.” It was Huggins calling from his cell phone.

When Nelson arrived, Huggins was sitting behind his desk with his glasses on. “Any time he has his glasses on, that means he’s been up all night watching tape,” Nelson said.

“How does a guy, who averages three points and two rebounds, have the nerve to make predictions that we’re going to blow somebody out?” Huggins asked.

He held up the newspaper. Nelson’s mouth dropped open. He started making excuses, claiming the interview was off the record. It wasn’t, of course.

“Why would you even say something so stupid?” Huggins said. “Now you’re going to give them bulletin board material. You’re going to fire them up. I don’t even think we’re good enough to beat these guys.”

Reporters in town were waiting for the Bearcats before practice. Van Exel started talking about how UC was going to win because Xavier’s Aaron Williams and the other post players were soft.

About 30 minutes into practice, Blount twisted his ankle and was carried off the floor.

“There goes our 6-10 post guy getting carted off like a slab of meat and you’re saying their post guys are soft!” Huggins yelled.

“You’re paranoid,” Van Exel shouted back.

Huggins kicked Van Exel out of practice.

Van Exel didn’t start the game the next night. Xavier full-court pressed, which worked to UC’s advantage. The Bearcats won 93-75.

Afterward, Huggins put him arm around Nelson and said, “Now, why don’t you retire undefeated with your predictions?”

IS THE FIX IN?

Huggins rarely got on Herb Jones. Jones was a quiet player who let his game do the talking. He worked on his game constantly and is perhaps one of the most underrated players in school history even though he was an honorable mention All-American in 1992.

UC took a 19-3 record into a February 20, 1992, game against DePaul at The Shoe. The Bearcats had won eight in a row. This night, however, they struggled—and nobody more than Jones, who finished four of 13 from the field with just nine points.

Huggins was ranting and raving in the locker room afterward. Jones sat with his head down.

“I don’t know what to think about you,” Huggins shouted at Jones. “Are you point shaving, Herb?”

Jones slowly raised his head and looked stunned. “What?” he said.

“It takes a lot to really make me mad,” Jones said. “I was fuming mad. I was mad when he said it to me, and I was mad at myself, too. That was probably the worst game of my life. To this day, I don’t know why I played so bad. From time to time, I think about that game. That was a real low moment for me.”

Several of the players remained in the locker room until 2 a.m. talking. Whatever they said struck a cord. The Bearcats won their next 10 games and didn’t lose again until the NCAA Tournament semifinals.

TAKE THAT

Two nights after the DePaul loss, Jones put on a display at South Alabama that even had his teammates shaking their heads.

He scored 17 consecutive points during a four-minute stretch of a 104-78 victory. He finished with 27 points on nine-of-13 shooting to go with eight rebounds.

“I was telling myself I had to play better,” Jones said. “I had to do more things to help the team win. I guess I was in a zone. I didn’t even know it.”

“That was something I couldn’t believe,” Buford said. “Herb loved playing on the road. He loved those hostile situations. He loved raising up and hitting that three and watching everybody go silent.”

YOU’VE GOT TO BE KIDDING?

UC was warming up before its March 7, 1992 game at Memphis when Jones followed a ball that had rolled off the court beyond the baseline. The crowd was close to the court, and when Jones picked up the ball, he came face to face with a rowdy Tigers fan.

“He looked at me, and I said, ‘How you doing?’” Jones said.

The man responded by screaming: “F—you. We hate you. You guys are always beating us.”

Jones couldn’t help it. He started laughing.

As it turns out, the man was right. UC beat Memphis that day 69-59 and would later defeat the Tigers—led by Anfernee Hardaway—in the Great Midwest Tournament and the NCAA Tournament.

A TEXAS (EL PASO) STANDOFF

UC was two victories from the Final Four and meeting Texas-El Paso in the Midwest Regional semifinals in Kansas City. UTEP was unranked; the Bearcats were No. 12 in the country. But the game turned out to be a nail-biter.

Nick Van Exel averaged 12.3 points and 18.3 points during his two seasons at UC. He was third-team Associated Press All-America as a senior in 1993, and was a second-round draft pick of the Los Angeles Lakers. Van Exel played 13 years in the NBA for six teams. He was an All-Star in 1998 and had a career-high 23 assists against Vancouver in January 1997. He finished his NBA career with 12,658 points and 5,777 assists. (Photo by Lisa Ventre/University of Cincinnati)

This didn’t help.

Van Exel had picked up a loose ball and fired a pass to a wide-open Jeff Scott, who missed the ball right by the UC basket. It went out of bounds. Huggins started yelling at Van Exel: “Don’t pass him the ball anymore. He doesn’t want the ball.” Van Exel was shouting back: “He was wide open. Shut up.” Huggins yanked Van Exel from the game and sat him on the bench.

With two free throws on its next possession, UTEP pulled within 60-57 with 7:44 left.

Blount was getting nervous. “It’s getting close again. Let Nick back in the game,” he told Huggins.

“(Forget) that!” Van Exel said. “I’m transferring! I’m going to New Mexico State next year.”

“That’s right,” Huggins yelled. “He doesn’t want to play. He wants to transfer. He can get out of here right now.”

Assistant coach John Loyer kept saying, “I think you need to put Nick back in the game.”

“No,” Huggins said. “He’s not ready.”

“I don’t care if I go back in the game anyway,” Van Exel said.

It was 62-59 with 4:12 remaining. Herb Jones was fouled and went to the line.

Blount, the mediator, was pleading with both parties. “Nick, come on, you’ve got to get back out there. Will you shut up? . . . Huggs, man, talk to him.”

“Do you want to play?” Huggins asked Van Exel.

Van Exel didn’t say a word. “Let’s just go win the game and we’ll discuss this afterwards,” Huggins said.

Jones missed his first free throw. Van Exel checked back into the game for A.D. Jackson. Jones made his second foul shot to make it 63-59.

UTEP would pull within two points twice in the final minute but couldn’t catch the Bearcats.

“We wouldn’t have won that game without Nick,” Nelson said.

CELEBRITIES UNCENSORED

Gibson wanted a way to remember the experience of going to the NCAA Tournament, so he asked a friend and former roommate from Cleveland whether he could borrow his video camera to record a sendoff at Shoemaker Center.

The friend didn’t see the video camera again until that summer.

“It never left my hand,” Gibson said. “I had that camera the entire tournament.”

In the final minutes of UC’s Midwest Regional final victory over Memphis in Kansas City, Gibson asked a student manager to go to the locker room to get the camera.

“I wanted to film the moment,” Gibson said. “He brought it back with about 50 seconds left. I went up to Huggs after the game was over and said, ‘How do you feel about going to the Final Four?’”

“It’s a long way from Dothan, ain’t it, Tarrance?” Huggins responded with a smile.

Gibson interviewed media members and teammates and kept that up all the way through the Final Four in Minneapolis.

TRASH TALK 101

As national media members descended upon Cincinnati to learn about the upstart Bearcats, six-foot-five Terry Nelson kept getting questions about how he was going to guard 6-9 Chris Webber, Michigan’s star player who was also 20-some pounds heavier.

“My goal is not to let him dunk on me,” Nelson said. “I don’t know how long it’ll last. On the break, that’s a different story. But, in the halfcourt, if he gets a rebound, he’ll be laying on the floor before he dunks on me.”

Nelson and Webber had never met—until right before the NCAA semifinals.

The UC players were shooting free throws and Webber came right up next to Nelson on the foul line. “Aren’t you the one who said you’re going to take me out? That I’m not dunking on you?”

“That’s right,” Nelson said.

“Man, don’t you know this is your last game?” Webber said.

“No, this is your last game,” Nelson replied.

The banter continued and included other players.

Webber kind of smirked and went back to the other side of the court.

Once the game started, Webber struck first with a half-hook shot over Nelson for the first points. Buford missed a three-pointer on UC’s next possession. Webber rebounded it, then tried to dribble. Nelson stole the ball just above the top of the three-point arc and went in for an uncontested dunk. The game was tied 2-2.

As he ran back down the court, Nelson bumped Webber and said, “Now it’s your turn.”

“He said, ‘Oh, you got me that time,’” Nelson said. “We talked the entire game. Normally, any team that talked trash to us, we got them out of their game. They were the only team that talked trash and won.”

Afterward, Webber—who finished with 16 points and 11 rebounds—gave Nelson a hug and said, “You all are fun. Nobody ever talks trash to us. You’re a good team. I like you all; let’s go hang out.”

Michigan won 76-72 before 50,379 at the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome in Minneapolis.

Nelson never saw Webber again.

GONE WITH THE WIND

Some of the Bearcats who played on the Final Four team will always feel they were treated as second-class citizens in Minneapolis. By fans. By some national media. By tournament organizers.

“We were treated just like garbage there,” Buford said. “We just felt really, really disrespected.”

“It’s just not right,” Huggins said.

The other teams all brought great story lines. There was Indiana and Bob Knight. Duke and Mike Krzyzewski, a former Knight assistant who had perhaps the top program in the country. Michigan and its Fab Five freshmen (Chris Webber, Jalen Rose, Jimmy King, Ray Jackson, Juwan Howard).

UC sports information director Tom Hathaway told Buford about a production meeting with TV representatives who talked about how they were going to present the teams during the telecast. They had met with officials from Duke, Indiana and Michigan—the other teams in the Final Four—to get their OK, but when it came to Cincinnati, Hathaway was told how it was going to be.

“They basically said, ‘We’re going to show some stuff about Oscar Robertson and we’re not going to have much on your team,’” Buford remembers being told. “Hathaway said he was kind of in shock.”

All of which is why Buford ending up throwing away the ring he received from the NCAA for being in the Final Four. He said it was silver with a black face that said “NCAA” on it. UC was on the team bus headed back to the airport in Minneapolis. Buford doesn’t remember when, but he recalls slipping the ring off his finger and pitching it out of the bus.

“It was a bad vibe,” Buford said. “And I felt like my memory of playing in the Final Four is all I need. The ring I got from UC I keep.”

STAND BY YOUR MAN

In September 1992, roughly six months after UC’s Final Four run, the Bearcats were gearing up for another shot at a national title. Six of the top eight players were returning.

Things were looking good—until the day Huggins called Corie Blount into his office to explain that he was being declared ineligible to play his final year at Cincinnati by the NCAA.

Blount had started his career at Rancho Santiago Junior College in 1988-89. He played four games his first season, then broke a bone in his foot that wouldn’t heal. He sat out the rest of that season, then played in 1989-90 and 1990-91. The NCAA considered 1988-89 a full season because it did not recognize medical redshirt years at the junior-college level until January 1992. So when Blount finished one year at UC, he was out of eligibility. UC officials appealed to the NCAA, the governing body of college athletics.

“Huggs said he was behind me 100 percent,” Blount said. “Based on the season I already had, of course, I wanted to play, but I wasn’t really disappointed. Huggs said I could stay at UC and get my degree. I didn’t really have the NBA in my mind back then. I never really could see that I would be a draft pick. I figured I’d have to try out to play somewhere.”

In October, the NCAA rejected Blount’s appeal and a UC compromise that Blount sit out four games of his senior season. “. . . We will not stop trying to right this wrong,” UC Athletic Director Rick Taylor told The Cincinnati Enquirer.

The NCAA did allow Blount to have the opportunity to appeal to an administrative review panel at the NCAA convention in January 1993. While Blount’s lawyer hinted at suing the NCAA, he ultimately decided to wait for the review panel to hear the case.

“I really didn’t know whether I was going to play again, but I knew I had a good chance,” Blount said. “It would’ve been a shock if they would’ve said, ‘No, you can’t play at all this year.’

“Rick (Taylor) was a hard little guy, but he would call me in his office, and I can honestly say he was telling me, ‘We’re going to do everything we possibly can to help you resolve this problem.’ I had a lot of people always telling me, ‘Don’t worry about it.’ That’s what made it easier for me.”

Meanwhile, the six-foot-10 Blount stayed in school and continued to work out on his own. When the Bearcats were on the road, Chuck Machock would work with Blount on post moves. Blount tried to stay in shape in case a new ruling occurred.

That’s what happened.

On January 15, 1993, the day the team was leaving for a game against DePaul in Chicago, Huggins told Blount to come along just in case his eligibility was restored.

In Chicago, the Bearcats had a team meeting to talk about what they wanted their record to be the rest of the way after Blount returned. He was in a hotel room with Van Exel and Martin when Huggins called Blount to his room. “Well, big fella, you’re back,” Huggins said with a smile, then he gave Blount a hug.

Blount played 28 minutes the next night, coming off the bench for eight points, seven rebounds and five assists. UC won 70-64.

EVERYONE WAS WATCHING

The summer after he left UC, Erik Martin was playing in an NBA summer league game when another player approached him. “Hey man, who’s the crazy guy who took his jersey off?” the guy wanted to know.

“That was me, but I ain’t crazy,” Martin told him. “You just have to know Huggs.”

The years may pass, but Martin can’t escape the moment on national television when he left the Bearcats’ bench in the middle of a game and stripped off his jersey on the way to the locker room. “I try to forget that, but you’d be surprised how many people still say, ‘Aren’t you the guy who took your jersey off?’”

Be assured, Martin has a sense of humor about it.

So, what did happen?

Cincinnati was playing host to DePaul at Shoemaker Center on January 30, 1993, for a noon game. Martin hated early games. So he was already groggy and in a bad mood when the game started.

But here is what he remembers:

Nick Van Exel threw a pass and a DePaul player tipped it out of bounds. Martin saw the tip and pulled back his hands, letting the ball go. The officials didn’t see the deflection and gave DePaul the ball.

“So Huggs took me out,” Martin said. “He’s screaming, and we’re going at each other. Let’s just say I said something to him, and he said, ‘Go to the locker room!’

“Usually when Huggs said that, you just leave it at that and sit there. That day I got up. I took off my jersey and threw it down. I can remember a fan asking, ‘Hey Erik, where ya going?’ I just kept walking.”

Martin said he went straight into the locker room, got undressed and took a shower. A student manager came in to tell Martin that assistant Steve Moeller said: “Don’t go anywhere.”

Moeller walked in at the next timeout.

“Where are you going?” he said.

“Back to the dorm,” Martin told him.

“No you’re not. You’re crazy. If you do that, you’re off the team,” Moeller said.

Soon, another assistant coach, Larry Harrison, came in and echoed that message.

Martin got dressed, sat and waited for halftime. He went into the coaches’ locker room and apologized to Huggins. There was a misunderstanding about what Martin had said. Huggins acknowledged that, hugged him and followed him into the locker room. UC was ahead 40-25.

“If coach Mo hadn’t come in, in five minutes I probably would’ve already been at the dorm,” Martin said. “When Huggs came in, he said something to me, but to be honest he didn’t dwell on that situation at all. He just said, ‘You’re going to start the second half.’

“My mom and (family) wanted to know what happened. I told people, reporters, fans, that stuff happens in practice all the time. They just happened to have the camera on me as I was walking out of the gym.

“I try not to regret anything I’ve done in life, but if I had a chance to do that over again, I wouldn’t have done it like that. But I’m an emotional person, so if that’s what came out that day, that’s what was supposed to come out.”

YOU OWE ME

UC was in the 1993 East Regional semifinals of the NCAA Tournament against Virginia at the Meadowlands in East Rutherford, N.J. Blount is a California guy who had never been to New York City.

The players were allowed to check out New York during the day, but Blount wanted to see more. Problem was, that night the team had an 11 p.m. curfew because there was a game the next day.

Teammate Mike Harris was from Brooklyn, N.Y., and he took Blount and Darrick Ford home to meet his family. Afterward, the three ran around New York for a while having fun. All of a sudden, they looked at a clock. It was 2 a.m.

The players hurried back to the hotel, walked into the lobby and saw the entire coaching staff sitting there waiting.

Huggins sent Ford and Harris to their rooms. He asked the other coaches to leave.

“Let me tell you something, Corie,” Huggins said. “You’ve got a chance to make more money than anybody on this team. But you’ll be happy going back to Monrovia (California), hanging out with your little gang-banging friends, talking about how I could’ve done this, I could’ve done that. You don’t understand the opportunity you have right now. We’ve got an opportunity to do some big things. And instead of you focusing on what we need to do, you’re out running around and breaking rules with two young guys.

Coach Huggins was prophetic when he told Corie Blount (44) that he had the potential to earn NBA riches if he was willing to dedicate himself to the game. Blount did, and was taken by the Chicago Bulls in the first round of the 1993 NBA draft. Blount played 11 NBA seasons for the Bulls, Los Angeles Lakers, Cleveland Cavaliers, Phoenix Suns, Golden State Warriors, Philadelphia 76ers, and Toronto Raptors. (Photo by University of Cincinnati/Sports Information)

“Look,” Huggins continued, “I’m going to play you tomorrow. But if you don’t play your ass off, I’m going to take your ass out as soon as I can.”

Blount ended up with 19 points and 11 rebounds in 33 minutes, and the Bearcats won 71-54.

NO PLACE LIKE HOME

Damon Flint remembers the day NCAA officials came to Woodward High School in April 1993 to interview him about his recruitment to Ohio State, the school with which he signed as a high school senior. Flint had hoped to team with Derek Anderson in the Buckeyes’ backcourt.

But the NCAA cited the Buckeyes for several violations in recruiting Flint. The most severe: Giving Woodward coach Jimmy Leon $60 for meals and transportation during an October 1991 visit to Columbus. The most petty: Ohio State coach Randy Ayers going to Woodward during a non-contact evaluation period to offer Flint condolences after his mother died in September 1991.

Flint still could have attended Ohio State—if he sat out his freshman year. However, the McDonald’s All-American felt he had worked too hard to achieve a high enough standardized test score to be academically eligible.

Flint decided to turn to the hometown school that had been recruiting him as long as he could remember: The University of Cincinnati. Flint knew Huggins and all the players. He was a frequent visitor to Shoemaker Center.

“I told Huggins I was coming,” he said. “I felt welcome.”

GETTING THE POINT

Flint was a great scorer in high school, averaging 29.4 points a game as a senior at Woodward. But when he got to UC, Huggins needed him to play point guard as a freshman because there really wasn’t a solid playmaker on the roster. Starting point guard Marko Wright broke his foot.

“He’s the boss,” Flint said. “We didn’t have anybody else to do it. But that’s the type of player I am. If we win, I’m happy. We won a lot. That was a big sacrifice.”

The Bearcats were 99-34 during his four years.

Flint finished his career with 1,316 points and was, at the time, third in career three-point field goals made and third in assists.

He never played point guard in high school but considered himself versatile enough to pull it off in college. “I didn’t want to be one dimensional,” he said.

Flint played shooting guard most of his last three seasons, but was also a backup point guard.

“I think in the end it was the best thing for Damon,” Huggins said. “Because Damon turned out to be a player, not just some guy who stood out there and shot.”

With all his offensive talent, Flint said his two most memorable games came on the defensive end.

During his freshman season, he went head to head against California guard Jason Kidd on February 20, 1994, in the 7-Up Shootout in Orlando, Florida The Bearcats lost 89-80, but Flint scored 26 points; Kidd had 22.

In the 1996 NCAA Tournament Southeast Regional semifinals, UC came up against Georgia Tech and its star guard Stephon Marbury. Flint held Marbury to 15 points on four-of-13 shooting and finished with 18 points, six rebounds and three assists. He was named Player of the Game, and UC won 87-70.

UC players Damon Flint (3), John Jacobs (55), Curtis Bostic (43), Marko Wright (5) and Mike Harris (32) celebrate after the Bearcats defeated Memphis 68-47 in the championship game of the 1994 Great Midwest Tournament. (Photo by Lisa Ventre/University of Cincinnati)

“I was definitely jacked up for that one,” Flint said. “That was Marbury’s last game. He told me right after the game that he was leaving early for the NBA.”

CROSSTOWN LETDOWN

No. 19 UC played rival Xavier, ranked No. 22, at a sold-out Cincinnati Gardens in January 1994.

This would be the only Crosstown Shootout for Cincinnati’s Dontonio Wingfield, and it would be a completely forgettable outing for the heralded freshman from Albany, Georgia.

Wingfield sat out the final 7:30 of the first half, and Xavier led 41-31 at intermission. Huggins was yelling at Wingfield in the locker room at halftime.

The Musketeers won 82-76 in overtime that night. Wingfield finished zero of seven from the field in 15 minutes; he barely played in the second half. Jackson Julson started the second half instead of Wingfield, who did not re-enter the game until 7:27 remained. His only two points of the night came on first-half free throws.

“He didn’t play well. He hurt us,” Huggins said afterward.

THE NON-HANDSHAKE

As it turned out, Wingfield was just a subplot for the evening. The main event was Huggins vs. Xavier coach Pete Gillen.

The context to this is, of course, that Huggins and Gillen were not—how shall we say this?—too fond of each other. The UC-Xavier rivalry may have peaked during this time because of the coaches’ dislike for one another.

At some point in the game, Huggins was yelling at one of the officials, when—according to the UC coaches—Gillen looked down the sideline and essentially shouted for Huggins to sit down and shut up.

“I pointed after a few things were said,” Huggins said afterward. “They need to coach their team and I’ll coach my team.”

Gillen said later that Huggins was trying to gain an advantage with the officials and that he was just trying to stick up for his team and “keep the officials from getting intimidated.” Huggins said some of the XU assistant coaches started shouting at him during the game.

When the game was over, the Xavier fans rushed the court. As Gillen approached Huggins, the UC coach refused to shake hands. That incensed Gillen.

“If I lost, I would’ve shaken hands,” Gillen said that night.

“I’m not a phony,” Huggins countered. “I’m not going to act like everything’s all right and shake hands after the game.”

The next morning, sitting in his office, Gillen suggested the schools should take a break from playing each other.

“It’s just sad, it’s a very bitter series,” he told The Cincinnati Enquirer. “We should definitely play next year, but then we might have to think about a cooling-off period . . .”

Never happened. Nor did Gillen ever have to coach in another Shootout. He left Xavier after the 1993-94 season to coach at Providence College.

HOW PROPHETIC

Just eight days removed from a devastating loss to Canisius College from Buffalo, N.Y., at Shoemaker Center in the Delta Airlines Classic (the Bearcats blew a 20-point lead), Cincinnati had a game at Wyoming on December 17, 1994.

The team was in a considerably better mood, having won at No. 11 Minnesota (91-88 in overtime) on December 14.

The Bearcats traveled right from Minneapolis to Laramie, Wyoming, to get adjusted to the thin air.

“It was going to be a fight against fatigue,” said LaZelle Durden, UC’s leading scorer and a team captain. “I pushed myself in practice to prepare for the situation.”

Cincinnati had two bad workouts leading up to the game. Huggins told his team: “LaZelle’s gonna have to score 50 for us to win because he’s the only one who’s practiced well.”

Well, Huggins was close. Durden ended up with 45 points in a dramatic 81-80 victory.

The Bearcats trailed all game and were behind 80-78 with 15 seconds remaining. Keith LeGree dribbled the ball upcourt for UC and passed to Durden. Durden went to the right side and, with time running out, took a one-handed, off-balance, three-point attempt from roughly 25 feet out. He missed it, but Wyoming’s LaDrell Whitehead fouled him in a call disputed afterward by Wyoming coach Joby Wright. “I wasn’t sure it would get called,” Durden said. “But I know for sure he fouled me.”

During a timeout, all the UC players were pumping up Durden. Jim Burbridge, an academic advisor who traveled with the team, pounded his chest and said: “Money. Nerves of steel.”

“That gave me confidence,” Durden said.

With no time remaining, Durden calmly made all three of his free throws to stun the crowd of 8,688.

“That was a dream come true for me,” Durden said. “I would say that was one of my highlights. . . . And that was the most tired I’ve ever been in my life.”

He finished 16 of 32 from the field, seven of 20 from three-point range and six of seven from the foul line, and totaled the most points for a Bearcat in 45 years.

In the locker room after the game, John Jacobs needled Huggins. “Coach, you lied to us,” Jacobs said. “You said LaZelle had to score 50 for us to win.”

CAL RIPKEN, WHO?

Around the middle of his senior year, in January 1996, Keith Gregor realized his one chance to land in the UC record books was with his consecutive games played streak.

Make no mistake: It was important to him.

“I’d be forever etched into the history books,” he said.

The school record for consecutive games played was held by Dwight “Jelly” Jones, who competed in 112 in a row from 1979-83.

In No. 109, Gregor turned his right ankle against Marquette at Shoemaker Center. He had scored 16 points in the first half and got injured in the first minute of the second half. UC would go on to win 91-70.

It wasn’t just his streak that was in jeopardy; the next game four nights later was against rival Xavier. That would be Gregor’s last Crosstown Shootout, and the Lakota High School graduate didn’t want to miss it.

He temporarily moved into his parents’ home in Cincinnati, and for three nights leading up to the Xavier game, Gregor didn’t sleep. He spent all night every night icing his ankle for 20 minutes, then taking ice off. Compression. More ice. No ice. Compression. More ice. No ice. Elevated foot. He watched west coast basketball games on ESPN and late-night movies on TBS.

“You can play if you’re tired,” Huggins reminded him. “But you can’t play if you can’t walk.”

Gregor tested his ankle the night before the XU game, making some cuts on the floor. He was about 90 percent. While loosening it up on game day, he actually weakened his ankle, and by tipoff he was hobbling.

He played a total of 22 minutes off the bench, running out of gas at the end. Gregor finished with four points, four rebounds and three assists. The Bearcats won 99-90. The streak was alive at 110.

The night he would tie “Jelly” Jones, UC was at home against DePaul. Gregor’s ankle was in bad shape, and Huggins told him he planned to rest him. Huggins said he’d let Gregor play at the end for a couple minutes to tie the record.

“I thought, that’s kind of a cheap way to keep it alive,” Gregor said. “But OK, Coach, whatever you say.”

UC struggled in the first half. Huggins kept going up to Gregor on the bench, saying, “Can we put you in now?” DePaul led 33-31 at halftime. Gregor felt OK.

“I think I can go, Coach,” he told Huggins.

“OK,” Huggins responded immediately. “You’re starting.”

Gregor played the whole second half. UC beat the Blue Demons 71-61.

He wouldn’t miss any games the rest of the way and finished with a school-record 131 consecutive games played.

“I always go down there to Shoemaker when Huggins has got a sophomore who’s played a lot and tell him ‘This kid needs to be benched for a game,’” Gregor said.

“(Steve) Logan broke most games played. That’s pretty good company to be in, I guess. I figure as long as Huggins is coaching, my streak is not going to be broken. If there’s anybody good enough as a freshman to come in and play there, they’ll probably be gone in three years.”

Gregor’s record was surpassed in 2014 by Sean Kilpatrick, who played in 140 consecutive games. Gregor currently ranks seventh in games played.

THE NICKNAME

During the summer before he entered ninth grade, Melvin Levett was playing in the Ohio Sports Festival. During one game, he went up and tomahawk dunked over an opposing player. “He seemed to hang in the air forever,” said Tom Erzen, the assistant coach. “I remembered a professional basketball player who was named the helicopter and I thought it was appropriate to say that about Melvin. I started calling Melvin the helicopter. Soon everyone was calling Melvin the helicopter!”

That didn’t stop in Cincinnati, especially after . . .

THE DUNK

UC vs. Alcorn State. December 3, 1997.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Levett said.

The Bearcats were 2-1 and had lost at home to Arizona State in the Preseason NIT Tournament at Shoemaker Center. Levett, a junior and one of the more talented players on the team, had averaged just 12 points in the first three games. He went three of 14 from the field in Game 3 against Morehead State.

“I was in a funk a little bit, because of my performances at the beginning of the season,” Levett said. “I was kind of down on myself. Huggs was letting me have it pretty good throughout that week. There was a certain point at halftime (against Alcorn) when we had a little shouting match. I guess it made me just say, ‘OK, now it’s time.’”

During the second half, Levett dunked twice in a row. But it was the third one that went down in UC folklore.

D’Juan Baker fired up a shot from the left side behind the three-point line.

“I saw it go up, and I just ran and jumped,” Levett said. “I never hesitated. I didn’t know where I was taking off from. I was going to get that basketball. I took off and I just kept going. I kept rising and rising.

“It hit the rim and bounced off the top of the backboard, and it came right into my hands as I was floating over Bobby Brannen and another guy from Alcorn State. I just slammed it home.”

Levett caught himself and ended up swinging on the rim. It would be called the Helicopter Dunk by many.

“There was a lot that went into that,” Levett said. “That was pretty much the one to say, ‘I’ve arrived for this season. I’m here. Now is the time to play ball.’ The season took off for me from there.”

In November 2001, Slam magazine included Levett among the 50 greatest dunkers of all time. He came in at No. 32, ahead of folks like Tracy McGrady, Chris Webber, Elgin Baylor, Scottie Pippen and Kevin Garnett. Topping the list (in order): Vince Carter, Michael Jordan, Dominique Wilkins, Julius Erving.

IN A ZONE

Less than three weeks later, Levett scored a career-high 42 points against Eastern Kentucky.

After practice a couple days before the game, Levett stayed in Shoemaker Center and had a shooting contest with guard John Carson. They put up several hundred shots. Some of the players stuck around to watch.

The touch stayed with him. When Levett was warming up before the EKU game, he couldn’t miss. Usually, as the adage goes, if a player doesn’t miss a shot during warmups, he’s in for a bad night.

But Levett’s first shot in the game fell, and he thought he had perfect extension on his follow through. Every time he let go, swish, the ball went right in. His shot hardly even touched the rim. Levett made 16 of 24 field goal attempts and was 10 of 14 from three-point range.

“It was one of those things that you watch on TV and you wish you were that guy in that moment, like when Mike (Jordan) had 63 in Boston or 69 against Cleveland,” Levett said. “You wish you could get in a zone like that. That day, I did. Whenever I am inconsistent with the form on my shot, I go back and watch that film.”

LOVE YOU, MOM

Ruben Patterson’s teammates learned a lot about him February 19, 1998.

Patterson and Alex Meacham were rooming together on a road trip to UAB. The night before the game, the two were talking when Patterson started opening up.

“He was talking about where he came from in Cleveland and how his goal was to get to the NBA and make lots of money,” Meacham said. “His dream was to buy his mother a car and a house and get her out of the ’hood. It was just a typical story of a guy wanting to do better for his family.

“We stayed up until 1:30, 2:00 in the morning. All he talked about was his mom.”

Finally, the two fell asleep with the television on. Around 6 a.m., there was a knock on the door. It was Huggins.

Huggins took Patterson back to his room and delivered some horrific news: Patterson’s mother, Charlene Patterson, had died of a heart attack in her sleep at age 38.

“Ruben was pretty shaken,” Levett said. “Basketball really didn’t matter at that point.”

At the team’s shootaround the day of the game, Huggins tried to convince Patterson to go home to be with his family.

“I’ll never forget this,” Meacham said. “Ruben said, ‘This is my family. I’m going to play this game.’”

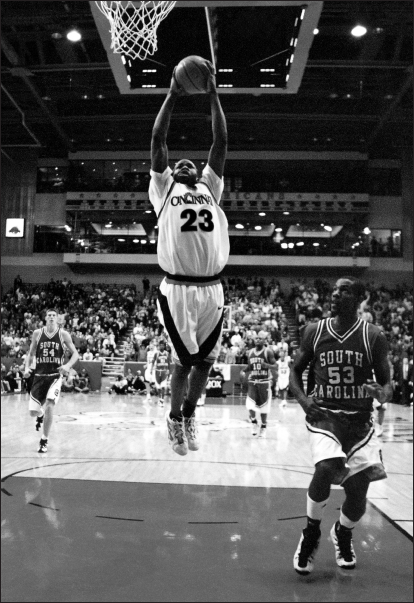

Ruben Patterson (23), an Associated Press honorable mention All-American in 1998, was selected by the Los Angeles Lakers in the second round of the NBA draft. Patterson played 10 years in the NBA and scored a total of 6,953 points for the Lakers, Seattle SuperSonics, Portland Trail Blazers, Denver Nuggets, Milwaukee Bucks, and Los Angeles Clippers. (Photo by Lisa Ventre/University of Cincinnati)

Back at the hotel, Patterson took his shoes and wrote on them with marker: “Charlene Patterson, #23” and “I am going to miss you.”

Then Patterson went out and had one of the best games of his career.

He scored a career-high 32 points and added seven rebounds, three assists and three steals in 37 minutes in a 93-76 victory. “We needed to win this game, and I wanted to play well for my mom,” Patterson said that night after the game. “Every time I scored, everybody saw me point up.”

“He was playing with an unbelievable amount of concentration defensively and offensively,” Meacham said. “And he had a glow to him while he played. After the game in the locker room, everybody was kind of crying. It was a real emotional thing. This is a weird thing to say but it was a good thing for our team in that it brought us a little closer together. And some guys saw a side of Huggins that they had never seen before. There was no doubt that Huggins, his staff and the players truly cared about Ruben and what happened.”

“That just shows you the kind of heart he had to overcome something so huge,” Levett said of Patterson. “I remember after the game every guy going down to the pay phones in the hotel and waiting to call home to tell their parents they loved them.”

THE AGONY OF DEFEAT

There were some tough losses during the Huggins era. The following certainly ranked up there:

UC was the No. 2 seed in the 1998 NCAA Tournament, and the selection committee sure set up an intriguing second-round matchup. After the Bearcats knocked off Northern Arizona in the first round, they earned a meeting with West Virginia.

The subplots? For starters, this was Huggins’s alma mater, the school for which he starred as an Academic All-American in the 1970s. He also coached a year for the Mountaineers as a graduate assistant. Coincidentally, West Virginia was coached by Gale Catlett, who left as UC’s coach 20 years earlier, took over as the Mountaineers’ coach and opted not to retain a young assistant coach named Bob Huggins.

Nice storylines, eh?

Cincinnati uncharacteristically went out and committed 22 turnovers yet remarkably had a chance to win the game. UC led 74-72 with 7.1 seconds remaining.

West Virginia inbounded the ball to Jarrod West, who dribbled to halfcourt and fired up a prayer. UC’s Patterson tipped the ball with his middle finger, changing the trajectory. It sailed into the basket for a three-pointer to win the game.

“I think my face was in the floor,” Levett said. “I couldn’t believe it. I really thought we had a curse on us. If you watch the ball leave his hands, you’ll see the rotation on it. It’s fast, but as Ruben tips it, it slows down but gains a little bit more flight. If that shot’s harder, if Ruben doesn’t touch it, we go to the Sweet 16 and possibly the Final Four.”

CREATING CAMARADERIE

Teams are allowed to take off-season trips every four years. The advantages: The players get to play games, but more important, they get to bond.

When UC went to Europe after the 1996-97 season, all the players shaved their heads bald. Except, of course, Bobby Brannen, who wasn’t going to cut his locks for anyone.

One day after visiting Vatican City in Italy, Darnell Burton, Flint and Levett went to a nightclub. It was a hole-in-the-wall place. Very dark inside.

Once they got seated, servers started bringing drinks, including bottles of champagne. Women were sitting with them. Nobody was speaking English, and the UC players didn’t know quite what was going on. After a while, Levett told Burton to find out why drinks were being brought to the table.

An employee told the players they owed $500 in lira, Italy’s currency at the time.

“What? We didn’t ask for this stuff,” the players protested.

“They took us to the back of the club,” Levett said. “It reminded you of one of those situations in a movie where you’re in a mob joint in some underground place and they want to take you in the back and chop you up. It just happened so quickly. Damon was talking fast. It was so confusing.

“We pull all the money out of our pockets and put it on the table and said, ‘This is all we’ve got.’ We didn’t get to $500, man. We were well short. We bolted out and walked down the street and we were quiet. Nobody said a word.”

Now that’s bonding.

“That was funny,” Burton said. “We were wondering why they were treating us like stars. We didn’t know they were keeping a tab on us. . . . We were a little scared. It was like one of those scenes from the mafia.”

LOOKING INTO THE FUTURE

He was a sophomore who had not yet established himself as a standout player. In fact, Kenyon Martin averaged fewer than 10 points a game and was not the kind of force that caused opposing coaches to alter their game plans.

So there was no way to prepare for what Martin unleashed on DePaul on February 21, 1998. Try this on for size: 24 points, 23 rebounds, 10 blocked shots.

“I was just being more aggressive than everybody,” Martin said. “I was grabbing everything and blocking every shot. Guys were scared to come to the hole.”

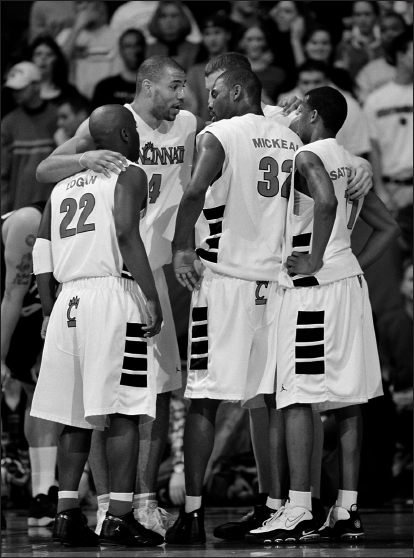

Kenyon Martin (4) gives instructions to teammates Steve Logan (22), Pete Mickeal (32) and Kenny Satterfield (right). (Photo by Lisa Ventre/University of Cincinnati)

It was only the 12th triple-double of any kind in UC history, and Martin was only the third player at the time to have one, joining Oscar Robertson and Rick Roberson. Robertson had 10 triple-doubles during his three seasons, and Roberson’s 16 points, 10 rebounds and 10 blocks came 30 years and one month earlier than Martin’s.

“Just watching from the sideline, it was unreal,” said UC teammate Jermaine Tate, who was sitting out that season after transferring from Ohio State. “I hadn’t seen a performance like that by an individual player in a game. It seemed like they were just throwing him the ball. It was unbelievable.”

Two years later, Martin would do it again. He finished with 28 points, 13 rebounds and 10 blocks against Memphis during his senior season.

GOOD MOVE

Martin did briefly consider leaving UC a year early for the NBA. Huggins was told by his NBA sources that Martin would be selected between Nos. 19 and 22 in the first round of the 1999 draft.

When he met with Huggins, the coach asked: “What do you want to do?”

Martin replied: “I want to win a national championship.”

“That was the only discussion we ever had about leaving early,” Huggins said.

CONFIDENCE BOOST

Martin averaged 2.8 points a game as a freshman, 9.9 points as a sophomore and 10.1 points as a junior. He was steadily improving and had a legendary work ethic. But mentally, he did not approach every game as if he were the dominant player on the court until he was a senior.

During the summer 1999, after his junior year, Martin was selected to the U.S. team for the World University Games in Palma del Morca, Spain. He was likely picked for his defense, to provide an intimidating presence near the basket.

Martin brought much more. He would lead the gold-medal-winning team in scoring (13.9 ppg) and rebounding (6.6 rpg). Dayton’s Oliver Purnell was the coach.

“A lot of people probably thought I was just going to be another guy on the team,” Martin said. “I came back with a different attitude about my game and my ability. That put me over the top. I worked the weight room hard. I worked on my game harder than I ever had. It always takes something for you to realize how good you can be. Those World University Games did it for me.”

Walk-on Alex Meacham remembers bumping into Martin when he returned from Spain. They were on their way to play pick-up games in Shoemaker Center. Meacham asked how the Games experience had been.

“I’ll never forget this,” Meacham said. “Kenyon said, ‘I don’t mean to brag, but I was probably the best guy on that team.’ When he left for those games, he was a little nervous. He knew he was going to be there with some of the best players in the country.”

In Shoemaker, team trainer Jayd Grossman told Meacham that he knew the trainer for the World University Games team, and the trainer had said Martin was the best player on the team—by far. That confirmed what Martin had said.

That day, Martin dominated the pick-up games.

“It came down to one thing: Kenyon knew he was a good player, but I don’t think Kenyon knew he was that good of a player,” Meacham said. “He worked out the same, shot the same amount. It was a mental thing.”

Huggins said a few other things happened in the summer of 1999: Martin learned to shoot free throws; he built up his leg strength; and he spent a lot of time with former Bearcat Corie Blount, who taught Martin “how to be a professional,” Huggins said.

The World University Games also helped Martin get past a game during his junior season that Huggins thinks affected him.

The Bearcats lost 62-60 at Charlotte on January 14, 1999. Trailing by two, UC threw the ball into Martin, who was fouled intentionally with three seconds left. “It was a gamble,” 49ers coach Bobby Lutz said afterward. Martin missed the front end of a one-and-one free throw situation, and Cincinnati lost.

“Kenyon’s such a good guy, he never wanted to hurt the team,” Huggins said. “So I think he didn’t want the ball at the end of games after that because he didn’t have a lot of confidence in making free throws. I think the World University Games helped him with that because he went to the line and made them.”

Martin made 13 of 19 free throws for the U.S. team, which included UC teammate Pete Mickeal.

HAPPY NEW YEAR

UC players may complain privately about Huggins when they’re on the team, but after their eligibility expires, most are extremely loyal to Huggins. All he has to do is ask for something, and it’s done.

On December 31, 1999, Huggins was at a junior college event in Florida. He called back to assistant coach Dan Peters and wanted the word put out that he needed some former Bearcats to show up for a New Year’s Day practice at Shoemaker Center. Huggins gave him phone numbers and said, “Tell those guys I need them at practice.”

“Huggs, those guys are not coming in on New Year’s Day,” Peters said.

“Pete, call them, they’ll be there,” Huggins said.

They all showed up.

“It really surprised me,” Peters said.

UC was 11-3, ranked third in the country and about to play host to UNLV on January 2. But Huggins thought his team needed a test, needed to learn how to compete.

And so they arrived for a little scrimmage: Terry Nelson. Tarrice Gibson. Anthony Buford. Curtis Bostic. A.D. Jackson. Keith Gregor. Donald Little, a freshman center, played with them.

“They just wore them out,” Huggins said.

“Could you at least let Satt cross half court so we can start our offense?” Huggins shouted to Gibson, referring to freshman Kenny Satterfield.