ON OR NEAR THE OLD TOWN’S MAIN SQUARE

The Slovak capital, Bratislava (brah-tee-SLAH-vah), long a drab lesson in the failings of the communist system, has become downright charming. Its old town bursts with colorfully restored facades, lively outdoor cafés, swanky boutiques, in-love-with-life locals, and (on sunny days) an almost Mediterranean ambience.

The rejuvenation doesn’t end in the old town. The ramshackle quarter to the east is gradually being flattened and redeveloped into a new forest of skyscrapers. The hilltop castle is getting a facelift. And even the glum commie suburb of Petržalka is undergoing a Technicolor makeover. Bratislava and Vienna have forged a new twin-city alliance for trade and commerce, bridging Eastern and Western Europe.

You sometimes get the feeling that workaday Bratislavans—who strike some visitors as gruff—are being pulled to the cutting edge of the 21st century kicking and screaming. But many Slovaks embrace the changes and fancy themselves as the yang to Vienna’s yin: If Vienna is a staid, elderly aristocrat sipping coffee, then Bratislava is a vivacious young professional jet-setting around Europe. Bratislava at night is a lively place; its very youthful center thrives. While it has tens of thousands of university students, there are no campuses as such—so the old town is the place where students go to play.

Bratislava’s priceless location—on the Danube (and the tourist circuit) smack-dab between Budapest and Vienna—makes it a very worthwhile “on the way” destination. Frankly, Bratislava used to leave me cold. But all the changes are positively inspiring.

A few hours are plenty to get the gist of Bratislava. Head straight to the old town and follow my self-guided walk, finishing with a stroll along the Danube riverbank to the thriving, modern Eurovea development. With more time, take advantage of one or more of the city’s fine viewpoints: Ascend to the “UFO” observation deck atop the funky bridge, ride the elevator up to the Sky Bar for a peek (and maybe a drink), or hike up to the castle for the views (but skip the ho-hum museum inside). If you spend the evening in Bratislava, you’ll find it lively with students, busy cafés, and nightlife.

Note that all museums and galleries are closed on Monday.

Day-Tripping Tip: Bratislava can be done as a long side-trip from Budapest (or a short one from Vienna), but it’s most convenient as a stopover to break up the journey between Budapest and Vienna. But pay careful attention to train schedules, as the Vienna connection alternates between Bratislava’s two train stations (Hlavná Stanica and Petržalka). If checking your bag at the station, be sure that your return or onward connection will depart from there.

Bratislava, with 430,000 residents, is Slovakia’s capital and biggest city. It has a small, colorful old town (staré mesto), with the castle on the hill above. This small area is surrounded by a vast construction zone of new buildings, rotting residential districts desperately in need of beautification, and some colorized communist suburbs (including Petržalka, across the river). The northern and western parts of the city are hilly and cool (these “Little Carpathians” are draped with vineyards), while the southern and eastern areas are flat and warmer.

The helpful TI is at Klobučnícka 2, on Primate’s Square behind the Old Town Hall (daily May-Sept 9:00-19:00, Oct-April 9:00-18:00, tel. 02/16186, www.visitbratislava.eu). Pick up the free Bratislava Guide (with map) and browse their brochures; they can help you find a room in town for a small fee. They also have a branch at the airport.

Discount Card: The TI sells the €10 Bratislava City Card, which includes free transit and sightseeing discounts for a full day—but it’s worthwhile only if you’re doing the old town walking tour (€14 without the card—see “Tours in Bratislava,” later; also available for €12/2 days, €15/3 days).

If you’re choosing which of Bratislava’s two train stations to use, consider this: Hlavná Stanica is far from welcoming, but it’s walkable to some accommodations and the old town; Petržalka (in a suburban shopping area) is small, clean, and modern, but you’ll have to take a bus into town. Frequent bus #93 connects the two stations (5-12/hour, 10 minutes; take bus #N93 after about 23:00). For public transit info and maps, see http://imhd.zoznam.sk.

Hlavná Stanica (Main Train Station): This decrepit and demoralizing station is about a half-mile north of the old town. It was still standing on my last visit...but barely. The city hopes to tear it down and start again from scratch. If those plans go forward, these arrival instructions could also become obsolete.

As you emerge from the tracks, the left-luggage desk is to your right (€2-2.50, depending on weight; look for úschovňa batožín; reconfirm open hours at the desk so you’ll be able to get your bags when you need them). There are also a few €2 lockers along track 1.

Getting from the Station to Downtown: It’s a 15-minute walk to the town center. Walk out the station’s front door and follow the covered walkway next to the looped bus drive; it will bend right and lead to a double pedestrian overpass. Cross the near arch and head downhill on the busy main drag, Štefánikova (named for politician Milan Štefánik, who worked for the post-WWI creation of Czechoslovakia). This once-elegant old boulevard is lined with Habsburg-era facades—some renovated, some rotting. In a few minutes, you’ll pass the nicely manicured presidential gardens on your left. Next comes the Grassalkovich Palace, Slovakia’s “White House” (with soldiers at guard out front), which faces the busy intersection called Hodžovo Námestie. The old town is just a long block ahead of you now. You can cross the intersection at street level or find the stairs and escalators down to the underground passageway (podchod). Head for the green steeple with an onion-shaped midsection. This is St. Michael’s Gate, at the start of the old town (and the beginning of my self-guided walk, described later).

To shave a few minutes off the trip, go part of the way by bus #93 or #X13 (after 23:00, use bus #N93). Walk out the station’s front door to the line of bus stops to the right. Buy a 15-minute ticket from the machines for €0.70 (select základný lístok—platí 15 minút, then insert coins—change given). Ride two stops to Hodžovo Námestie, across from Grassalkovich Palace, then walk straight ahead toward the green steeple, passing a pink-and-white church.

Tram #13 is another option from the station, if it’s running again (the tracks have been closed for construction). Trams (električky) use the same tickets as buses; ride to the Poštová stop, then walk straight down Obchodná street toward St. Michael’s Gate.

Petržalka Train Station (ŽST Petržalka): Half of the trains from Vienna arrive at this small, quiet train station, across the river in the modern suburb of Petržalka (PET-ur-ZHAL-kuh). From this station, ride bus #93 (direction: Hlavná Stanica) or #94 (direction: STU) four stops to Zochova (the first stop after the bridge, near St. Michael’s Gate); after 23:00, use bus #N93. Buy a €0.70/15-minute základný lístok ticket (described earlier).

For information on Bratislava’s buses, riverboats, and airport, see “Bratislava Connections,” at the end of this chapter.

Money: Slovakia uses the euro (€1=about $1.40). You’ll find ATMs at the train stations and airport.

Language: The official language is Slovak, which is closely related to Czech and Polish—although many Bratislavans also speak English. The local word used informally for both “hi” and “bye” is easy to remember: ahoj (pronounced “AH-hoy,” like a pirate). “Please” is prosím (PROH-seem), “thank you” is đakujem (DYAH-koo-yehm), “good” is dobrý (DOH-bree), and “Cheers!” is Na zdravie! (nah ZDRAH-vyeh).

Phone Tips: To call locally within Bratislava, dial the number without the area code. To make a long-distance call within Slovakia, start with the area code (which begins with 0). To call from Hungary to Slovakia, dial 00-421, then the area code minus the initial zero, then the number (from the US, dial 011-421-area code minus zero, then the number). To call from Slovakia to Hungary, you’d dial 00-36, then the area code (minus the initial zero) and number.

Internet Access: Free Wi-Fi hotspots are at the three major old town squares (Main Square, Primate’s Square, and Hviezdoslav Square). You’ll see signs advertising computer terminals around the old town.

Local Guidebook: For in-depth suggestions on Bratislava sightseeing, dining, and more, look for the excellent and eye-pleasing Bratislava Active guidebook by Martin Sloboda (see “Tours in Bratislava,” next; around €10, sold at every postcard rack).

The TI offers a one-hour old town walking tour in English every day in the summer at 14:00 (€14, free with €10 Bratislava City Card; book and pay at least two hours in advance). Those arriving by boat will be accosted by guides selling their own 1.5-hour tours (half on foot and half in a little tourist train, €10, in German and English).

MS Agency, run by Martin Sloboda (a can-do entrepreneur and tireless Bratislava booster, and author of the great local guidebook described earlier), can set you up with a good guide (€130/3 hours, €150/4 hours); he can also help you track down your Slovak roots. Martin, who helped me put this chapter together, is part of the generation that came of age as communism fell and whose energy and leadership are reshaping the city (mobile 0905-627-265, www.msagency.sk, sloboda@msagency.sk).

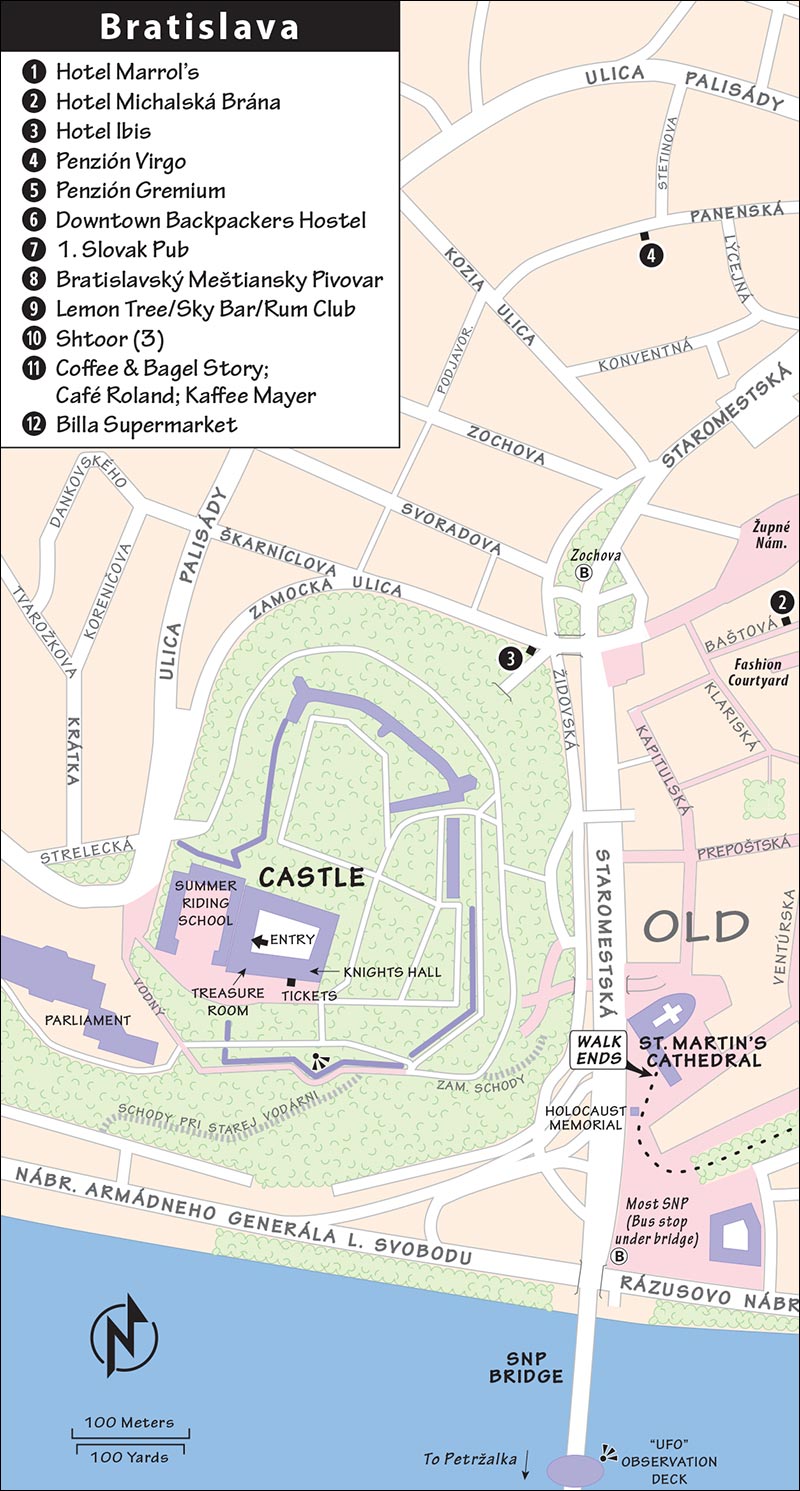

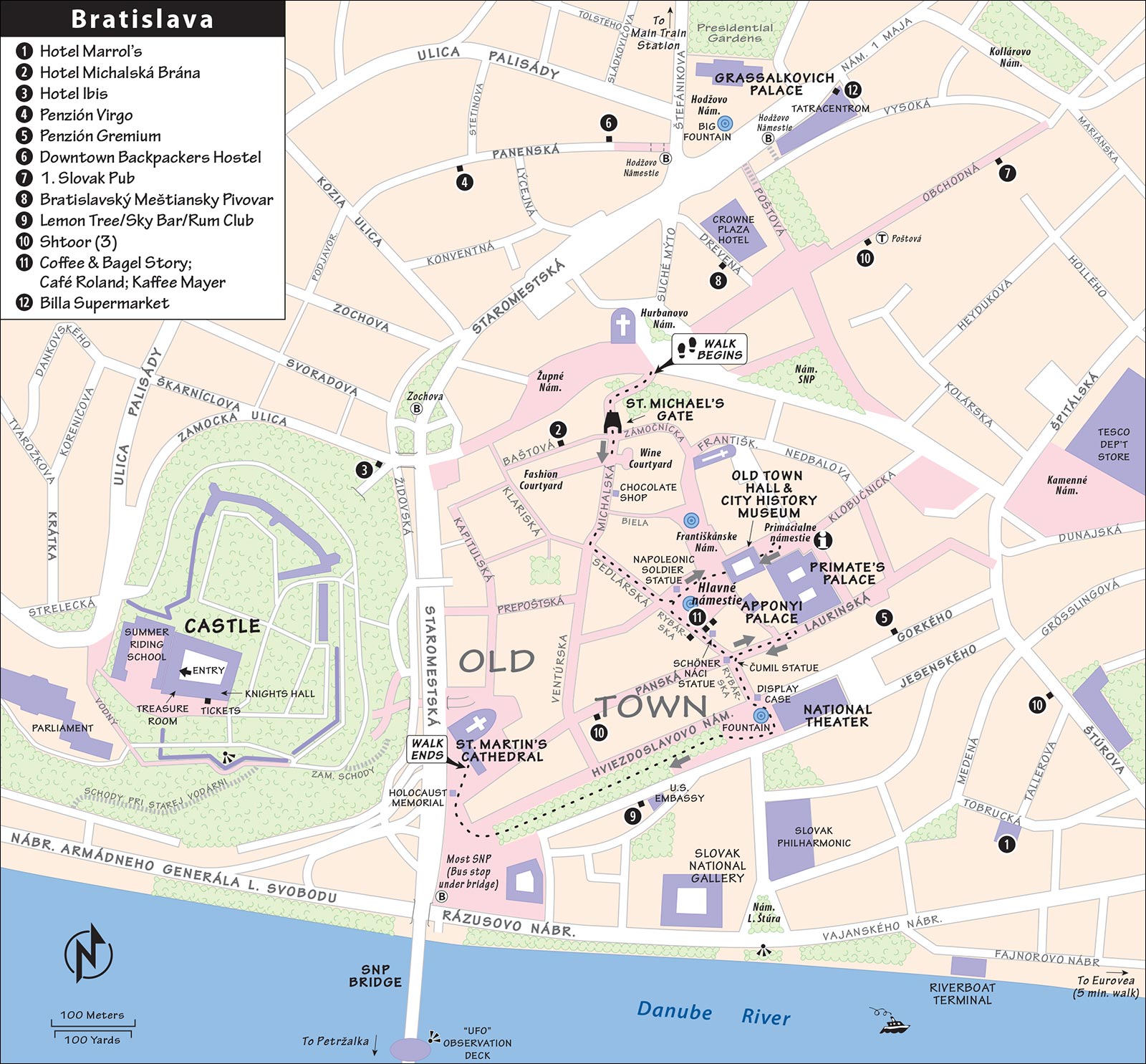

(See "Bratislava" map, here.)

This self-guided orientation walk passes through the heart of delightfully traffic-free old Bratislava and then down to its riverside commercial zone (figure 1.5 hours, not including stops, for this walk). If you’re coming from the station, make your way toward the green steeple of St. Michael’s Gate (explained in “Arrival in Bratislava,” earlier). Before going through the passage into the old town, peek over the railing on your left to the inviting garden below—once part of the city moat.

• Step through the first, smaller gate, walk along the passageway, and pause as you come through the green-steepled...

This is the last surviving tower of the city wall. Just below the gate, notice the “kilometer zero” plaque in the ground, marking the point from which distances in Slovakia are measured.

• You’re at the head of...

Pretty as it is now, the old center was a decrepit ghost town during the communist era, partly because WWII bombing left Bratislava a damaged husk. The communist regime believed that Bratislavans of the future would live in large, efficient apartment buildings. They saw the old town as a useless relic of the bad old days of poor plumbing, cramped living spaces, social injustice, and German domination—a view which left no room to respect the town’s heritage. In the 1950s, they actually sold Bratislava’s original medieval cobbles to cute German towns that were rebuilding themselves with elegant Old World character. Locals avoided this desolate corner of the city, preferring to spend time in the Petržalka suburb across the river.

With the fall of communism in 1989, the new government began a nearly decade-long process of restitution—sorting out who had the rights to the buildings, and returning them to their original owners. During this time, little repair or development took place (since there was no point investing in a property until ownership was clearly established). By 1998, most of these property issues had been sorted out, and the old town was made traffic-free. The city replaced all the street cobbles, spruced up the public buildings, and encouraged private owners to restore their property. (If you see any remaining decrepit buildings, it’s likely that their ownership is still in dispute.)

The cafés and restaurants that line this street are inviting, especially in summer. Poke around behind the facades and outdoor tables to experience Bratislava’s charm. Courtyards and passageways—most of them open to the public—burrow through the city’s buildings. For example, a half-block down Michalská street on the left, the courtyard at #12 was once home to vintners; their former cellars are now coffee shops, massage parlors, crafts boutiques, and cigar shops. Across the street, on the right, the dead-end passage at #5 has an antique shop and small café, while #7 is home to a fashion design shop.

On the left (at #6), the Cukráreň na Korze chocolate shop is highly regarded among locals for its delicious hot chocolate and creamy truffles (Mon-Thu 9:00-21:00, Fri-Sat 9:00-22:00, Sun 10:00-21:00, tel. 02/5443-3945).

Above the shop’s entrance, the cannonball embedded in the wall recalls Napoleon’s two sieges of Bratislava (the 1809 siege was 42 days long), which caused massive suffering—even worse than during World War II. Keep an eye out for these cannonballs all over town...somber reminders of one of Bratislava’s darkest times.

• Two blocks down from St. Michael’s Gate, where the street jogs slightly right (and its name changes to Ventúrska), detour left along Sedlárska street and head to the...

A modest Town Hall square that feels too petite for a national capital, this is the centerpiece of Old World Bratislava. Cute little kiosks, with old-time cityscape engravings on their roofs, sell local handicrafts and knickknacks (Easter through October). Similar stalls fill the square from mid-November until December 23, when the Christmas market here is a big draw (www.vianocnetrhy.sk).

Virtually every building around this square dates from a different architectural period, from Gothic (the yellow tower) to Art Nouveau (the fancy facade facing it from across the square).

Cafés line the square. You can’t go wrong here. Choose the ambience you like best (indoors or out) and sip a drink with Slovakia’s best urban view. The Art Nouveau Café Roland, once a bank, is known for its 1904 Klimt-style mosaics and historic photos of the days when the city was known as Pressburg (Austrian times) or Pozsony (Hungarian times). The barista stands where a different kind of bean counter once did, guarding a vault that now holds coffee (Hlavné Námestie 5; the café may have a new name by the time you visit). The classic choice is the kitty-corner Kaffee Mayer. This venerable café, an institution here, has been selling coffee and cakes to a genteel clientele since 1873. You can enjoy your pick-me-up in the swanky old interior or out on the square (€3-3.50 cakes, small selection of expensive-for-Bratislava hot meals, daily 9:30-22:00, Fri-Sat until 23:00, Hlavné Námestie 4, tel. 02/5441-1741).

Peering over one of the benches on the square is a cartoonish statue of a Napoleonic officer (notice the French flag marking the embassy right behind him). With bare feet and a hat pulled over his eyes, it’s hardly a flattering portrait—you could call it the locals’ revenge for Napoleon’s sieges. Across the square, another soldier from that period stands at attention.

At the top of the Main Square is the impressive Old Town Hall (Stará Radnica), with its bold yellow tower. Near the bottom of the tower (to the left of the window), notice another cannonball embedded in the facade—yet another reminder of Napoleon’s impact on Bratislava. Over time, the Old Town Hall grew, annexing the buildings next to it and creating a mishmash of architectural styles along this side of the square. (A few steps down the street to the right are the historic apartments and wine museum at the Apponyi House—described later, under “Sights in Bratislava.”)

Step through the passageway into the Old Town Hall’s gorgeously restored courtyard, with its Renaissance arcades. (The City History Museum’s entrance is here—described later.)

Then, to see another fine old square, continue through the other end of the courtyard into Primate’s Square (Primaciálne Námestie). The pink mansion on the right is the Primate’s Palace, with a fine interior decorated with six English tapestries (described later). At the far end of this square is the TI.

• Backtrack to the Main Square. With your back to the Old Town Hall, go to the end of the square and follow the street to the left (Rybárska Brána). On your way you’ll pass a pair of...

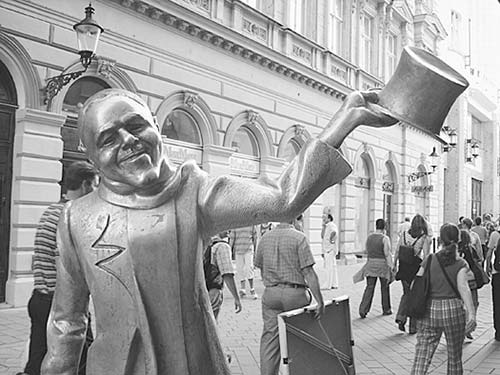

Playful statues (such as the Napoleonic officer we met earlier) dot Bratislava’s old town. Most date from the late 1990s, when city leaders wanted to entice locals back into the newly prettied-up center.

Just at the beginning of the street, as you exit the main square, you’ll come to a jovial chap doffing his top hat. This is a statue of Schöner Náci, who lived in Bratislava until the 1960s. This eccentric old man, a poor carpet cleaner, would dress up in his one black suit and top hat, and go strolling through the city, offering gifts to the women he fancied. (He’d often whisper “schön”—German for “pretty,” which is how he got his nickname.) Schöner Náci now gets to spend eternity greeting visitors outside his favorite café, Kaffee Mayer. Once he lost an arm: A bunch of drunks broke it off. (It was replaced.) As Prague gets more expensive, Bratislava has become one of the cheaper alternatives for weekend “stag parties,” popular with Brits lured here by cheap flights and cheap beer.

• Continue down Rybárska.

At the end of this block, at the intersection with Panská, watch out on the right for Čumil (“the Peeper”), grinning at passersby from a manhole. This was the first—and is still the favorite—of Bratislava’s statues. There’s no story behind this one—the artist simply wanted to create a fun icon and let the townspeople make up their own tales. Čumil has survived being driven over by a truck—twice—and he’s still grinning.

• Keep along Rybárska to reach the long, skinny square called...

The landscaping in the center of this square makes it particularly inviting. At the near end is the impressive, silver-topped Slovak National Theater (Slovenské Národné Divadlo). Beyond that, the opulent yellow Neo-Baroque building is the Slovak Philharmonic (Slovenská Filharmónia). When the theater opened in the 1880s, half the shows were in German and half in Hungarian. Today, it’s a proud Slovak institution—typical of the ethnic changes that have marked this city’s life.

Right in front of the theater (by the McDonald’s), look down into the glass display case to see the foundation of the one-time Fishermen’s Gate into the city. Surrounding the base of the gate is water. This entire square was once a tributary of the Danube, and the Carlton Hotel across the way was a series of inns on different islands. The buildings along the old town side of the square mark where the city wall once stood. Now the square is a lively zone on balmy evenings, with several fine restaurants (including some splurgy steakhouses) offering al fresco tables jammed with visiting European businessmen looking for good-quality, expense-account meals.

Stroll down the long art-and-people-filled square. Each summer, as part of an arts festival, it’s ornamented with entertaining modern art. After passing a statue of the square’s namesake (Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav, a beloved Slovak poet), you’ll come upon an ugly fence and barriers on the left, which mark the fortified US Embassy. Just past the embassy is the low-profile entrance to the Sky Bar, an affordable rooftop restaurant with excellent views (ride elevator to seventh floor; see “Eating in Bratislava,” later). Farther along, after the giant chessboard, the glass pavilion is a popular venue for summer concerts. On the right near the end of the park, a statue of Hans Christian Andersen is a reminder that the Danish storyteller enjoyed his visit to Bratislava, too.

• Reaching the end of the square, you run into the barrier for a busy highway. Turn right and walk one block to find the big, black marble slab facing a modern monument—and, likely, a colorful wooden reconstruction of a synagogue.

This was the site of Bratislava’s original synagogue. You can see an etching of the building in the big slab.

Turn your attention to the memorial. The word “Remember” carved into the base in Hebrew and Slovak commemorates the 90,000 Slovak Jews who were deported to Nazi death camps. Nearly all were killed. The fact that the town’s main synagogue and main church (to the right) were located side by side illustrates the tolerance that characterized Bratislava before Hitler. Ponder the modern statue: The two pages of an open book, faces, hands in the sky, and bullets—all under the Star of David—evoke the fate of 90 percent of the Slovak Jews.

• Now head toward the adjacent church, up the stairs.

If the highway thundering a few feet in front of this historic church’s door were any closer, the off-ramp would go through the nave. Sad as it is now, the cathedral has been party to some pretty important history. While Buda and Pest were occupied by Ottomans from 1543 to 1689, Bratislava was the capital of Hungary. Nineteen Hungarian kings and queens were crowned in this church—more than have been crowned anywhere in Hungary. In fact, the last Hungarian coronation (not counting the Austrian Franz Josef) was not in Budapest, but in Bratislava. A replica of the Hungarian crown still tops the steeple.

It’s worth walking up to the cathedral’s entrance to observe some fragments of times past (circle around the building, along the busy road, to the opposite, uphill side). Directly across from the church door is a broken bit of the 15th-century town wall. The church was actually built into the wall, which explains its unusual north-side entry. In fact, notice the fortified watchtower (with a WC drop on its left) built into the corner of the church just above you.

There’s relatively little to see inside the cathedral—I’d skip it (€2, Mon-Sat 9:00-11:30 & 13:00-18:00, Sun 13:30-16:00). If you do duck in, you’ll find a fairly gloomy interior, some fine carved-wood altarpieces (a Slovak specialty), a dank crypt, a replica of the Hungarian crown, and a treasury in the back with a whimsical wood carving of Jesus blessing Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef.

Head back around the church for a good view (looking toward the river) of the huge bridge called Most SNP, the communists’ pride and joy (the “SNP” stands for the Slovak National Uprising of 1944 against the Nazis, a typical focus of communist remembrance). As with most Soviet-era landmarks in former communist countries, locals aren’t crazy about this structure—not only for the questionable Starship Enterprise design, but also because of the oppressive regime it represented. However, the restaurant and observation deck up top have been renovated into a posh eatery called (appropriately enough) “UFO.” You can visit it for the views, a drink, or a full meal.

• You could end the walk here. Two sights (both described later, under “Sights in Bratislava”) are nearby. To hike up to the castle, take the underpass beneath the highway, go up the stairs on the right marked by the Hrad/Castle sign, then turn left up the stepped lane marked Zámocké Schody. Or hike over the SNP Bridge (pedestrian walkway on lower level) to ride the elevator up the UFO viewing platform.

But to really round out your Bratislava visit, head for the river and stroll downstream (left) to a place where you get a dose of modern development in Bratislava—Eurovea. Walk about 10 minutes downstream, past the old town and boat terminals until you come to a big, slick complex with a grassy park leading down to the riverbank.

Just downstream from the old town is the futuristic Eurovea, with four vibrant layers, each a quarter-mile long: a riverside park, luxury condos, a thriving modern shopping mall, and an office park. Walking out onto the view piers jutting into the Danube and surveying the scene, it looks like a computer-generated urban dreamscape come true. Exploring the old town gave you a taste of where this country has been. But wandering this riverside park, enjoying a drink in one of its chic outdoor lounges, and then browsing through the thriving mall, you’ll enjoy a glimpse of where Slovakia is heading.

• Our walk is finished. If you haven’t already visited them, consider circling back to some of the sights described next.

If Europe had a prize for “capital city with the most underwhelming museums,” I’d cast my vote for Bratislava. You can easily have a great day here without setting foot in a museum. Focus instead on Bratislava’s street life and the grand views from the castle and UFO restaurant. If it’s rainy or you’re in a museum-going mood, the Primate’s Palace (with its cheap admission and fine tapestries) ranks slightly above the rest.

These museums are all within a few minutes’ walk of one another, on or very near the Main Square.

Bratislava’s most interesting museum, this tastefully restored French-Neoclassical mansion (formerly the residence of the archbishop, or “primate”) dates from 1781. The religious counterpart of the castle, it filled in for Esztergom—the Hungarian religious capital—after that city was taken by the Ottomans in 1543. Even after the Ottoman defeat in the 1680s, this remained the winter residence of Hungary’s archbishops.

Cost and Hours: €3, Tue-Fri 10:00-17:00, Sat-Sun 11:00-18:00, closed Mon, Primaciálne Námestie 1, tel. 02/5935-6394, www.bratislava.sk.

Visiting the Museum: The palace, which now serves as a government building, features one fine floor of exhibits. Follow signs for Expozícia up the grand staircase to the ticket counter. There are three main attractions: the Mirror Hall, the tapestries, and the archbishop’s chapel.

The Mirror Hall, used for concerts, city council meetings, and other important events, is to the left as you enter and worth a glance (if it’s not closed for an event).

A series of large public rooms, originally designed to impress, are now an art gallery. Distributed through several of these rooms is the museum’s pride, and for many its highlight: a series of six English tapestries, illustrating the ancient Greek myth of the tragic love between Hero and Leander. The tapestries were woven in England by Flemish weavers for the court of King Charles I (in the 1630s). They were kept in London’s Hampton Court Palace until Charles was deposed and beheaded in 1649. Cromwell sold them to France to help fund his civil war, but after 1650, they disappeared. Centuries later, in 1903, restorers broke through a false wall in this mansion and discovered the six tapestries, neatly folded and perfectly preserved. Nobody knows how they got there (perhaps they were squirreled away during the Napoleonic invasion, and whoever hid them didn’t survive). The archbishop—who had just sold the palace to the city, but emptied it of furniture before he left—cried foul and tried to get the tapestries back...but the city said, “A deal’s a deal.”

After traipsing through the grand rooms, find the hallway that leads through the smaller rooms of the archbishop’s private quarters, now decorated with minor Dutch, Flemish, German, and Italian paintings. At the end of this hall, a bay window looks down into the archbishop’s own private marble chapel. When the archbishop became too ill to walk down to Mass, this window was built for him to take part in the service.

On your way back to the entry, pause at the head of the larger corridor to study a 1900 view of the then much smaller town by Gustáv Keleti. The museum’s entry hall also has grand portraits of Maria Theresa and Josef II.

Delving into the bric-a-brac of Bratislava’s past, this museum includes ecclesiastical art on the ground floor and a sprawling, chronological look at local history upstairs. The displays occupy rooms once used by the town council—courthouse, council hall, chapel, and so on. Everything is described in English, and the included audioguide tries hard, but nothing quite succeeds in bringing meaning to the place. On your way upstairs, you’ll have a chance to climb up into the Old Town Hall’s tower, offering so-so views over the square, cathedral, and castle.

Cost and Hours: €5, includes audioguide, €6 combo-ticket with Apponyi House, Tue-Fri 10:00-17:00, Sat-Sun 11:00-18:00, closed Mon, last entry 30 minutes before closing, in the Old Town Hall—enter through courtyard, tel. 02/5920-5130, www.muzeum.bratislava.sk.

This nicely restored mansion of a Hungarian aristocrat is meaningless without the included audioguide (dull but informative). The museum has two parts. The cellar and ground floor feature an interesting exhibit on the vineyards of the nearby “Little Carpathian” hills, with historic presses and barrels, and a replica of an old-time wine-pub table. Upstairs are two floors of urban apartments from old Bratislava, called the Period Rooms Museum. The first floor up shows off the 18th-century Rococo-style rooms of the nobility—fine but not ostentatious, with ceramic stoves. The second floor up (with lower ceilings and simpler wall decorations) illustrates 19th-century bourgeois/middle-class lifestyles, including period clothing and some Empire-style furniture.

Cost and Hours: €4, includes audioguide, €6 combo-ticket with City History Museum, Tue-Fri 10:00-17:00, Sat-Sun 11:00-18:00, closed Mon, last entry 30 minutes before closing, Radničná 1, tel. 02/5920-5135, www.muzeum.bratislava.sk.

This imposing fortress, nicknamed the “upside-down table,” is the city’s most prominent landmark. The oldest surviving chunk is the 13th-century Romanesque watchtower (the one slightly taller than the other three). When Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa took a liking to Bratislava in the 18th century, she transformed the castle from a military fortress to a royal residence suitable for holding court. She added a summer riding school (the U-shaped complex next to the castle), an enclosed winter riding school out back, and lots more. Maria Theresa’s favorite daughter, Maria Christina, lived here with her husband, Albert, when they were newlyweds. Locals nicknamed the place “little Schönbrunn,” in reference to the Habsburgs’ summer palace on the outskirts of Vienna.

Turned into a fortress-garrison during the Napoleonic Wars, the castle burned to the ground in an 1811 fire started by careless soldiers, and was left as a ruin for 150 years before being reconstructed in 1953. Unfortunately, the communist rebuild was drab and uninviting; the inner courtyard feels like a prison exercise yard.

A more recent renovation has done little to improve things, and the museum exhibits inside aren’t really worth the cost of admission (described next). The best visit is to simply hike up (it’s free to enter the grounds), enjoy the views over town, and take a close-up look at the stately old building (the big, blocky, modern building next door is the Slovak Parliament).

For details on the best walking route to the castle, see here.

The newly restored castle has a few sights inside, with more likely to open in the future. Two small exhibits are skippable: the misnamed Treasure Room (a sparse collection of items found at the castle site, including coins and fragments of Roman jugs) and the Knights Hall (offering a brief history lesson in the castle’s construction and reconstruction). You can also enter the palace itself. A blinding-white staircase with gold trim leads to the Music Hall, with a prized 18th-century Assumption altarpiece by Anton Schmidt (first floor); a collection of historical prints depicting Bratislava and its castle (second floor); and temporary exhibits (third/top floor). From the top floor, a series of very steep, modern staircases take you up to the Crown Tower (the castle’s oldest and tallest) for views over town—though the vista from the terrace in front of the castle is much easier to reach and nearly as good.

Cost and Hours: €6 all-inclusive “Road A” ticket, €2 for pointless “Road B” ticket (covers only the less interesting parts of palace—the Treasure Room and Knights Hall); Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon; ticket office is right of main riverfront entrance—enter exhibits from passage into central courtyard, tel. 02/2048-3110, www.snm.sk.

Bratislava’s bizarre, flying-saucer-capped bridge, completed in 1972 in heavy-handed communist style, has been reclaimed by capitalists. The flying saucer-shaped structure called the UFO (at the Petržalka end of the bridge) is now a spruced-up, overpriced café/restaurant and observation deck, allowing sweeping 360-degree views of Bratislava from about 300 feet above the Danube. Think of it as the Slovak Space Needle.

Cost and Hours: €6.50, daily 10:00-23:00, elevator free if you have a meal reservation or order food at the restaurant—main courses steeply priced at €23-28, restaurant opens at 12:00, tel. 02/6252-0300, www.redmonkeygroup.com.

Getting There: The elevator entrance is underneath the tower. Walk across the bridge from the old town (there are pedestrian walkways on the lower level). If you take the downstream (old-town side) walkway, you’ll pass historical photos of the bridge’s construction, including the demolition of the city’s synagogue and other old town buildings.

Self-Guided Tour: The “elevator” that takes you up is actually a funicular—you’ll notice you’re moving at an angle. At the top, walk up the stairs to the observation deck.

Self-Guided Tour: The “elevator” that takes you up is actually a funicular—you’ll notice you’re moving at an angle. At the top, walk up the stairs to the observation deck.

Begin by viewing the castle and old town. The area to the right of the old town, between and beyond the skyscrapers, is a massive construction zone. A time-lapse camera set up here over the next few years will catch skyscrapers popping up like dandelions. International investors are throwing lots of money at Bratislava. (Imagine having so much prime, undeveloped real estate available downtown in the capital of an emerging European economic power...and just an hour down the road from Vienna, no less.) Most of the development is taking place along the banks of the Danube. In a decade, this will be a commercial center.

The huge TV tower caps a forested hill beyond the old town. Below and to the left of it, the pointy monument is Slavín, where more than 6,800 Soviet soldiers who fought to liberate Bratislava from the Nazis are buried. Under communist rule, a nearby church was forced to take down its steeple so as not to draw attention away from the huge Soviet soldier on top of the monument.

Now turn 180 degrees and cross the platform to face Petržalka, a planned communist suburb that sprouted here in the 1970s. The site was once occupied by a village, and the various districts of modern Petržalka still carry their original names (which now seem ironic): “Meadows” (Háje), “Woods” (Lúky), and “Courtyards” (Dvory). The ambitious communist planners envisioned a city laced with Venetian-style canals to help drain the marshy land, but the plans were abandoned after the harsh crackdown on the 1968 Prague Spring uprising. Without the incentives of private ownership, all they succeeded in creating was a grim and decaying sea of miserable concrete apartment paneláky (“panel buildings,” so-called because they’re made of huge prefab panels).

Today, one in four Bratislavans lives in Petržalka, and things are looking better. Like Dorothy opening the door to Oz, the formerly drab buildings have been splashed with bright new colors. Far from being a slum, Petržalka is a popular neighborhood for Bratislavan yuppies who can’t yet afford to build their dream houses. Locals read the Czech-language home-improvement magazine Panel Plus for ideas on how to give their panelák apartments some style (browse it yourself at www.panelplus.cz).

Petržalka is also a big suburban-style shopping zone (note the supermall down below). But there’s still some history here. The park called Sad Janka Kráľa (originally, in German, Aupark)—just downriver from the bridge—was technically the first public park in Europe in the 1770s and is still a popular place for locals to relax and court.

Scanning the horizon beyond Petržalka, two things stick out: on the left, the old communist oil refinery (which has been fully updated and is now state-of-the-art); and on the right, a sea of modern windmills. These are just over the border, in Austria...and Bratislava is sure to grow in that direction quickly. Austria is about three miles that way, and Hungary is about six miles farther to the left.

Before you leave, consider a drink at the café (€3-4 coffee or beer, €7-20 cocktails). If nothing else, be sure to use the memorable WCs (guys can enjoy a classic urinal photo).

I’d rather sleep in Budapest (or in Vienna)—particularly since good-value options in central Bratislava are slim, and service tends to be surly. Business-oriented places charge more on weekdays than on weekends. Expect prices to drop slightly in winter and in the hottest summer months. Hotel Michalská Brána is right in the heart of the old town, while the others are just outside it—but still within a 5-10-minute walk.

$$$ Hotel Marrol’s, on a quiet street, is the town’s most enticing splurge. Although the immediate neighborhood isn’t interesting, it’s a five-minute walk from the old town, and its 54 rooms are luxurious and tastefully appointed, Old World country-style. While pricey, the rates drop on weekends (prices flex, but generally Mon-Thu: Db-€160, Fri-Sun: Db-€120, Sb-€10 less, non-smoking, elevator, air-con, Wi-Fi, loaner laptops, free minibar, gorgeous lounge, Tobrucká 4, tel. 02/5778-4600, www.hotelmarrols.sk, rec@hotelmarrols.sk).

$$ Hotel Michalská Brána is a charming boutique hotel just inside St. Michael’s Gate in the old town. The 14 rooms are sleek, mod, and classy, and the location is ideal—right in the heart of town, but on a relatively sleepy lane just away from the hubbub (Sb-€69-73, Db-€79-83, higher prices are for Mon-Thu nights, extra bed-€20, pricier suites available, non-smoking, air-con, elevator, Wi-Fi, Baštová 4, tel. 02/5930-7200, www.michalskabrana.sk, reception@michalskabrana.com).

$$ Hotel Ibis, part of the Europe-wide chain, offers 120 nicely appointed rooms just outside the old town, overlooking a busy tram junction—request a quieter room (Mon-Thu: Sb/Db-€85, Fri-Sun: Sb/Db-€69, rates flex with demand, you’ll likely save €20 or more with advance booking on their website, breakfast-€10, elevator, air-con, guest computer and Wi-Fi, Zámocká 38, tel. 02/5929-2000, www.ibishotel.com, h3566@accor.com).

$$ Penzión Virgo sits on a quiet residential street, an eight-minute walk from the old town. The 11 boutiqueish rooms are classy and well-appointed (Sb-€61, Db-€74—but often discounted to around Sb/Db-€55, extra bed-€13, breakfast-€6, Wi-Fi, inexpensive parking, Panenská 14, tel. 02/3300-6262, www.penzionvirgo.sk, reception@penzionvirgo.sk).

$$ Penzión Gremium has six nondescript rooms and three apartments in a very central location, just a block behind the National Theater and a few steps from the old town. It’s on a busy street with good windows but no air-conditioning, so it can be noisy on rowdy weekends (Sb-€60, Db-€70, Db apartment-€90, prices soft, breakfast-€7, elevator reaches some rooms, Wi-Fi, Gorkého 11, tel. 02/2070-4874, www.penziongremium.sk, recepcia@penziongremium.sk).

$ Downtown Backpackers Hostel is a funky but well-run place located in an old-fashioned townhouse. Rooms are named for famous artists and decorated with reinterpretations of their paintings (45 beds in 7 rooms, D-€54, bunk in 7-8-bed dorm-€18, bunk in 10-bed dorm-€17, breakfast-€3-5, Wi-Fi, free laundry facilities, kitchen, bike rental nearby, Panenská 31—across busy boulevard from Grassalkovich Palace, 10 minutes on foot from main station, tel. 02/5464-1191, mobile 0905/259-714, www.backpackers.sk, info@backpackers.sk).

(See "Bratislava" map, here.)

Today’s Slovak cooking shows some Hungarian and Austrian influences, but it’s closer to Czech cuisine—lots of starches and gravy, and plenty of pork, cabbage, potatoes, and dumplings. Keep an eye out for Slovakia’s national dish, bryndzové halušky (small potato dumplings with sheep’s cheese and bits of bacon). For a fun drink and snack that locals love, try a Vinea grape soda and a sweet Pressburger bagel in any bar or café.

Like the Czechs, the Slovaks produce excellent beer (pivo, PEE-voh). One of the top brands is Zlatý Bažant (“Golden Pheasant”). Bratislava’s beer halls are good places to sample Slovak and Czech beers, and to get a hearty, affordable meal of stick-to-your-ribs pub grub. Long a wine-producing area, the Bratislava region makes the same wines that Vienna is famous for. But, as nearly all is consumed locally, most people don’t think of Slovakia as wine country.

Bratislava is packed with inviting new eateries. In addition to the heavy Slovak staples, you’ll find trendy new bars and bistros, and a smattering of ethnic offerings. The best plan may be to stroll the old town and keep your eyes open for the setting and cuisine that appeals to you most. Or consider one of these options.

1. Slovak Pub (“1.” as in “the first”) attracts a student crowd. Enter from Obchodná, the bustling shopping street just above the old town, and climb the stairs into a vast warren of rustic, old countryside-style pub rooms with uneven floors. Enjoy the lively, loud, almost chaotic ambience while dining on affordable and truly authentic Slovak fare, made with products from the pub’s own farm. This is a good place to try the Slovak specialty, bryndzové halušky (several varieties for €4-5; €4-12 main courses, Mon 10:00-23:00, Tue-Sat 10:00-24:00, Sun 12:00-24:00, Obchodná 62, tel. 02/5292-6367, www.slovakpub.sk).

Bratislavský Meštiansky Pivovar (“Bratislava Town Brewpub”), just above the old town behind the big Crowne Plaza hotel, brews its own beer and also sells a variety of others. Seating stretches over several levels in the new-meets-old interior (€7-15 main courses, Mon-Sat 11:00-24:00, Sun 11:00-23:00, Drevená 8, mobile 0944-512-265, www.mestianskypivovar.sk).

Lemon Tree/Sky Bar/Rum Club, a three-in-one place just past the fenced-in US Embassy on the trendy Hviezdoslavovo Námestie, features the same Thai-meets-Mediterranean menu throughout (€8-12 pasta and noodle dishes, €16-19 main courses). But the real reason to come here is for the seventh-floor Sky Bar, with fantastic views of the old town and the SNP Bridge. It’s smart to reserve a view table in advance if you want to dine here—or just drop by for a pricey vodka cocktail on the small terrace. You’ve got the best seat in town, and though prices are expensive for Bratislava, they’re no more than what you’d pay for a meal in Vienna (daily 11:00-late, Sun from 12:00, Hviezdoslavovo Námestie 7, mobile 0948-109-400, www.spicy.sk).

At Eurovea (the recommended end to my walking tour, 10 minutes downstream from the old town), huge outdoor terraces rollicking with happy eaters line the swanky riverfront residential and shopping-mall complex. You’ll pay high prices for the great atmosphere and views at international eateries—French, Italian, Brazilian—and a branch of the Czech beer-hall chain Kolkovna. Or you can head to the food court in the shopping mall, where you’ll eat well for €4.

Shtoor is a hip, rustic-chic café (named for a revered 19th-century champion of Slovak culture, Ľudovít Štúr) with coffee drinks and €3-5 sandwiches and quiches (takeaway or table service, open long hours daily). They have three locations: in the heart of the old town at Panská 23; just east of the old town (near Eurovea) at Štúrova 8; and inside a Barnes & Noble-type bookstore, Martinus.sk, at Obchodná 26.

Coffee & Bagel Story (a chain) sells...coffee and €3 takeout bagel sandwiches. The handiest location is on the town’s main square at Hlavné Námestie 8, with picnic tables right out front.

Supermarket: Try Billa, in the Tatracentrum complex across the street from Grassalkovich Palace (Mon-Sat 7:00-22:00, Sun 8:00-20:00).

Bratislava has two major train stations: the main station closer to the old town (Hlavná Stanica, abbreviated “Bratislava hl. st.” on schedules) and Petržalka station (sometimes called ŽST Petržalka), in the suburb across the river (for full details, see “Arrival in Bratislava,” earlier). When checking schedules, pay attention to which station your train uses.

From Bratislava by Train to: Budapest (7/day direct, 2.75 hours to Keleti Station, more with transfers; also doable—and possibly cheaper—by Orange Ways bus, 1-4/day, 2.5 hours, www.orangeways.com), Vienna (2/hour, 1 hour; buy the €15 round-trip EU Regio day pass, which is cheaper than a one-way fare; departures alternate between the two stations—half from main station, half from Petržalka), Sopron (at least hourly, 2.5-3 hours, usually 2 transfers—often at stations in downtown and/or suburban Vienna), Prague (5/day direct, 4.25 hours). To reach other Hungarian destinations (including Eger and Pécs), it’s generally easiest to change in Budapest; for Austrian destinations (such as Salzburg or Innsbruck), you’ll connect through Vienna.

Two different companies run handy buses that connect Bratislava, Vienna, and the airports in each city: Blaguss/Eurolines (www.blaguss.sk or www.eurolines.at) and Slovak Lines/Postbus (tel. 0810-222-3336, www.postbus.at or www.slovaklines.sk). You can book ahead online, or (if arriving at the airport) just take whichever connection is leaving first. The bus schedules are handily posted at www.airportbratislava.sk (find the “Navigation—From the Airport” tab).

The buses run about hourly from Bratislava’s airport to Bratislava (15 minutes, stops either at the main bus station east of the old town or at the Most SNP stop underneath the SNP Bridge), continues on to Vienna’s airport (1 hour), and ends in Vienna (1.25 hours, Erdberg stop on the U-3 subway line). They then turn around and make the reverse journey (€7.50-10, depending on route).

Riverboats connect Bratislava to Vienna. Conveniently, these boats dock right along the Danube in front of Bratislava’s old town. While they are more expensive, less frequent, and slower than the train, some travelers enjoy getting out on the Danube. It’s prudent to bring your passport if crossing over for the day (though it’s unlikely anyone will ask for it).

The Twin City Liner offers three to five daily boat trips between a dock at the edge of Bratislava’s old town, along Fajnorovo nábrežie, and Vienna’s Schwedenplatz (where Vienna’s town center hits the canal; €30-35 each way, 1.25-hour trip; can fill up—reservations smart, Austrian tel. 01/58880, www.twincityliner.com).

The competing Slovak LOD line connects the cities a little more cheaply, but just twice a day. These boats are slower, as they use Vienna’s less-convenient Reichsbrücke dock on the main river, farther from the city center (€23 one-way, €38 round-trip, 1.5-hour trip, tel. 02/5293-2226, www.lod.sk).

You have two options for reaching Bratislava: You can fly into its own airport, or into the very nearby Vienna Airport.

This airport (airport code: BTS, www.letiskobratislava.sk) is six miles northeast of downtown Bratislava. Budget airline Ryanair (www.ryanair.com) has many flights here. Some airlines market it as “Vienna-Bratislava,” thanks to its proximity to both capitals. It’s compact and manageable, with all the usual amenities (including ATMs).

From the Airport to Downtown Bratislava: The airport has easy public bus connections to Bratislava’s main train station (Hlavná Stanica, €1.30, bus #61, 4-5/hour, 30 minutes). To reach the bus stop, exit straight out of the arrivals hall, cross the street, buy a ticket at the kiosk, and look for the bus stop on your right. For directions from the train station into the old town, see “Arrival in Bratislava,” earlier. A taxi from the airport into central Bratislava should cost less than €20.

To Budapest: Take the bus or taxi to Bratislava’s main train station (described above), then hop a train to Budapest.

To Vienna: Take either the Slovak Lines/Postbus bus, which runs to Vienna’s Hauptbahnhof (every 1-2 hours, 2-hour trip, €7.70, www.slovaklines.sk or www.postbus.at) or the Blaguss/Eurolines bus to the Erdberg stop on Vienna’s U-3 subway line, on which it’s a straight shot to Stephansplatz or Mariahilfer Strasse (every 1-2 hours, 1.5-hour trip, €7.20, www.blaguss.sk or www.eurolines.at). A taxi from Bratislava Airport directly to Vienna costs €60-90 (depending on whether you use a cheaper Slovak or more expensive Austrian cab).

This airport, 12 miles from downtown Vienna and 30 miles from downtown Bratislava, is well-connected both to both capitals (airport code: VIE, airport tel. 01/700-722-233, www.viennaairport.com).

To reach Bratislava from the airport, the easiest option is to take the Blaguss/Eurolines or Slovak Lines/Postbus bus described earlier (under “By Bus”). Ask the TI which bus is leaving first, then head straight out the door and hop on. After about 45 minutes, the bus drops off in downtown Bratislava, then heads to the airport. I’d skip the train connection, which takes longer and involves complicated changes (airport train to Wien-Mitte Bahnhof in downtown Vienna, S-Bahn/subway to Südbahnhof, train to Bratislava, figure 1.75 hours total).