1922

407A

Grünewald1

18 January 1922

Dear Professor,

You will have heard from Rank that I am prepared to leave on Sunday the 22nd, thus to reach Vienna on Monday afternoon. I hope to find you and your family in the best of health. But I must make it very clear that my journey is again threatened. Today's morning papers report that a railway strike is imminent in Saxony. Since the lines via both Passau and Prague go through Saxony, you must be prepared for my calling it off at the last minute. If necessary, I can leave a little earlier and try to go a roundabout way to catch the connection in Passau.

Meanwhile I hope everything will go well.

With the most cordial greetings from house to house.

Yours,

Abraham

1. Postcard.

408A

Berlin-Grünewald

13 March 1922

Dear Professor,

It is a long time since I was in Vienna, and you have not had any direct news since then. I only wrote to your wife after my return home to thank you all for the pleasant days in Vienna. Everything that has happened since has found room in the circular letter, and, since in Vienna I again had the opportunity of seeing how your correspondence keeps you busy far into the night, I feel even more reluctant than before to add to your burden. At other times, however, my wish to report to you gains the upper hand, and today I am giving in to this for a change.

My load of work is frequently so overwhelming that it prevents me from ploughing my way, as I would like to, through certain problems in my spare time. Particularly the problems of manic-depressive states. Nevertheless, my two analyses in this field give me a great deal of information in their daily sessions, and some of the questions we discussed in the autumn are beginning to take more definite shape. I think the parallels to kleptomania, which also stems from the oral phase and represents the biting-off of penis or breast, are quite interesting. The regression of the melancholic has the same aim, only in a different form.1

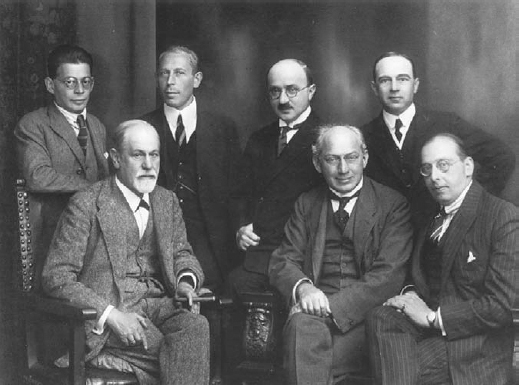

The “Secret Committee” in Vienna—front row, left to right: Sigmund Freud, Sándor Ferenczi, Hanns Sachs; back row, left to right: Otto Rank, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Ernest Jones (1922).

The taking in of the love-object is very striking in my cases. I can produce very nice material for this concept of yours, revealing the process in all its detail. In this connection I have a small request—for an offprint of “Mourning and Melancholia”, which would be extremely helpful to me in my work. Many thanks in anticipation.

One brief comment on this piece of work! You, dear Professor, state that you miss in the course of normal mourning a process that would correspond to the swing-over from melancholia to mania. I think, however, that I could identify such a process, without knowing whether this reaction is regularly found. My impression is that a fair number of people show an increase in libido some time after a bereavement. It shows itself in heightened sexual need and appears quite often to lead, e.g., to conception shortly after a bereavement.2 Sometime at your convenience I should like to know what you think about this and whether you can confirm this observation. The increase in libido some time after “object-loss” would seem to be a good addition to the parallel between mourning and melancholia.—

What you told me about pseudologia phantastica has been fully confirmed for me. My female patient's quite fantastic lies do in fact correspond to a psychological truth.3

I should like to mention briefly that I shall in the near future speak in our Society on a special form of parapraxis. I shall soon be dictating this short paper4 and shall send it off to Rank. It is about those slips that, like obsessional actions, do not permit the repressed tendency to break through but overcompensate for it.

About our doings here I can tell you that my wife and I went to see Oliver once, when he was still in bed, and recently we had him with us for an evening. The knee injury appears to be healing.

In analytic circles here there is nothing new apart from what was reported in the circular letter.

I hope you are all well. I can say the same of us. At present we are already making plans for the summer (St Anton on the Arlberg?). Before that, however, my wife will have to go to a thermal bath for her sciatica.

Another small comment. At a recent meeting, one of our members drew our attention to an interesting misprint. In your Kleine Schriften IV, “History of the Ψα Movement”, in the footnote on p. 74—“discredition” instead of “discretion”. This misprint does not occur in the original (Jahrbuch der Ψα). How the type-setter made the error is less interesting than the fact that it was overlooked in proof-reading. The intention of discrediting Jung comes to the fore in a most amusing way.5

With many cordial greetings to your whole house, also in my wife's name!

Yours,

Karl Abraham

1. Cf. Abraham, 1917c: pp. 483, 485, 498.

2. Cf. Abraham, 1917c: 472–473.

3. Cf. Abraham, 1917c: 483–484.

4. Abraham, 1922[78].

5. Freud had used the report of a patient of Jung's to criticize the latter's technique, by adding “that I cannot allow that a psycho-analytic technique has any right to claim the protection of medical discre[di]tion” (1914d: p. 64).

409F

Vienna IX, Berggasse 19

30 March 1922

Dear Friend,

After more than a fortnight I decide to reread your kind private letter and discover your request for a reprint, which for some reason made no impact on me when I received it.

I plunge with pleasure into the abundance of your scientific insights and intentions, only I wonder why you do not take into account at all my last suggestion about the nature of mania after melancholia (in the Mass Psychology).1 Might that be the motivation for my forgetting about the “Mourning and Melancholia”? For analysis, no absurdity is impossible. I would still have felt like discussing all these things—particularly with you—but no possibility of writing about them. In the evening I am lazy, and above all there is the urgent “business” correspondence, cancelling lectures, journeys, collaborations, and the like, which stands in the way of a decent exchange of ideas with one's friends. I am now doubly glad that we instituted the circular letters. With eight and soon nine hours' work, I do not manage to achieve the composure required for scientific work. At Gastein, between 1 July and 1 August, I hope to be able to commit to paper some little things that I told you about in the Harz.2

The rest of the summer, from 1 August until the middle of September, is still as blank as the map of Central Africa was in my schooldays.3 The Austrian summer is going to be a difficult problem. Meanwhile the spring is also appalling.

You will see my daughter before I do,4 and you are no doubt in contact with my two sons as well. Our house is quite lonely, enlivened at present only by the semi-young American niece.5 Of your American audience only one is still here, Dr Polon.6 But Dr Frink7 is to come back on 26 April. Mrs Strachey was dangerously ill, so that both she and her husband have broken off the analysis.8 Substitutes always move in on time; at present I have three Swiss people: Sarasin,9 the Kempner woman10 and a young Dr Blum from Zurich,11 three English, Rickman,12 that proud woman Riviere,13 whom you will surely remember from The Hague, and a Prof. Tansley from Cambridge,14 who is starting tomorrow, and two Americans, including the only full patient. At Easter a Dutch dottoressa15 who has just received her doctorate is to take over from Dr Polon. I find character analyses with pupils more difficult in many respects than with professional neurotics, but admittedly I have not yet worked out the new technique.

My cordial greetings to your dear wife and the two rapidly growing children. I did not know your wife had acquired such an obstinate sciatica.

Do let yourself be carried away into writing a private letter again to your faithful

Freud

1. Freud, 1921c: pp. 132–133.

2. “Psycho-analysis and Telepathy” (Freud, 1941d [1921]). “The MS. bears at its beginning the date ‘2 Aug. 21’ and at its end ‘Gastein, 6 Aug. 21’” (editor's note in S.E. 18: p. 175).

3. On 30 June, Freud and Minna Bernays went to Gastein; on 1 August they went on to Berchtesgaden, where they were joined by Martha, Anna, Oliver, the Hollitschers, and Ernst and Lucie. In Berchtesgaden Freud wrote The Ego and the Id (1923b), was visited by Eitingon, and analysed Frink. On 14 September Freud and Anna went to Hamburg, from where they arrived in Berlin on the 21st, where the VIIth International Psychoanalytic Congress was held from 25 to 27 September 1922.

4. Anna had left Vienna on 2 March for Hamburg via Berlin for a stay with her nephews and brother-in-law. On 19 April she went to Berlin and on 25 April to Lou Andreas-Salomé in Göttingen, returning home on 5 May (Freud/Anna Freud correspondence, LOC).

5. Judith (“Ditha”) Bernays [1885–1977], daughter of Freud's brother-in-law Eli Bernays [1860–1923] and his sister Anna [1858–1955].

6. Albert Polon [1881–1926], neurologist, m.d. 1910 Cornell University Medical College.

7. Horace Westlake Frink [1883–1935], professor of neurology at Cornell University Medical College [1914], founding member of the New York Psychoanalytic Society, its first secretary [1911], and president in 1913 and 1923. During a previous analysis, in 1921, “Freud advised Frink…to divorce his wife and marry a former patient…The prospect set off a series of manic depressive episodes, and Frink returned twice to Freud for more analysis…. As Frink's state deteriorated, he sought treatment with Adolf Meyer, was divorced by his second wife” (Hale, 1995: p. 29), but “never fully recovered” (Hale, 1971a: p. 387; cf. Edmunds, 1988).

8. Alix, née Sargant-Florence [1892–1973], and James Strachey [1887–1967], best known today for their work on what became known as the Standard Edition. Prominent members of the “Bloomsbury” group, including James's brother Lytton, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, analysts Karin and Adrian Stephen (Virginia's brother), John Maynard Keynes, Clive Bell, Saxon Sydney-Turner, and Roger Fry, among others. Both had started analysis with Freud in October 1920. Although Alix's analysis soon had to be interrupted because of illness, she and James were declared fit to practice analysis by Freud. Associate Members [1922] and Members [1923] of the British Society. In 1924/ 25, Alix continued analysis with Abraham. (Cf. Meisel & Kendrick, 1986; Roazen, 1995; and the vast “Bloomsbury” literature.)

9. Philipp Sarasin [1888–1968], M.D., from Basel. He had worked at the Burghölzli [1915]—where he had had analysis with Franz Riklin—and at the psychiatric clinic in Rheinau, Switzerland [1916–1921]. After his analysis with Freud, he settled in Basel in private practice. Long-term president of the Swiss Society [1928–1960]. (See Walser, 1976/77: p. 473.)

10. Salomea Kempner [1880–194?], from Plock, Poland, formerly assistant doctor at the clinic in Rheinau. In 1921 she had moved to Vienna and in 1923 to Berlin, where she worked at the polyclinic. Member of the Swiss, Vienna, and Berlin Societies, consecutively. She disappeared in the Warsaw ghetto. (Cf. Mühlleitner, 1992: pp. 181–182.)

11. Ernst Blum [1892–1981]. After his analysis with Freud, in 1924 he settled as a neurologist, psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst in Bern (Weber, 1991). “He had a wide range of interests and assumed an independent point of view within Swiss psychoanalysis” (Moser, 1992: p. 295).

12. John Rickman [1891–1951], M.D., associate member [1920], member [1922], and president [1948] of the British Society. Also analysand of Ferenczi's [1928–31] and Melanie Klein's (prior to the Second World War). Rickman “played a key role in the early administration of the Society and Institute, in its publications activities and its link with allied professions” (King & Steiner, 1991: p. xviii). Having belonged first to Melanie Klein's group, he was later considered part of the “Middle Group” and took an active part in the compromise with Anna Freud.

13. Joan Riviere [1883–1962], in analysis with Freud since February 27 (Freud to Riviere, 5 February 1922, LOC). She had already been in analysis with Ernest Jones [1915]. Riviere was a founding member of the British Society [1919], an important translator of Freud's, translation editor of the International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, and member of the Glossary Committee. Riviere later supported Melanie Klein. There are numerous references to her sharp intellect and tongue.

14. Sir Arthur George Tansley [1871–1955], British botanist and plant ecologist, a friend of James Strachey's. Founder of the science of ecology (Payne, 1956). Member of the British Society.

15. Adriana (Jeanne) de Groot [1895–1987], M.D., in analysis with Freud from 1922 to 1925, and again in 1931. In 1925 she moved to Berlin and married analyst Hans Lampl. Between 1933 and 1938 again in Vienna, then in the Netherlands. Member of the Dutch [1925], German [1926], and Vienna [1933] Societies. (Cf. Mühlleitner, 1992: pp. 202–204.)

410A

Berlin-Grünewald

2 May 1922

Dear Professor,

Your forthcoming birthday gives me a welcome excuse to write to you once again outside the framework of the circular letters. Thus this letter is filled with best wishes. As far as I am aware, I have no need to overcompensate for bad wishes, and a few words will therefore suffice to assure you once again of the cordiality of my affection.

As on several former occasions, I am once again enclosing a small contribution1 for the Zeitschrift as a birthday present, in the hope that it will interest you and meet with your approval.

Your letter of 30 March is still waiting for a reply, while I have already thanked you for the reprint of “Mourning and Melancholia”. I fully understand your forgetting it. Your failure in sending the paper I asked for was meant to indicate that I should first of all study the other source (Mass Psychology). Now, I am quite familiar with its contents concerning the subject of mania and melancholia, but, in spite of going through it once again, I cannot see where I went wrong. I can find no mention anywhere of a parallel in normal cases, i.e. the onset of a reaction state after mourning that can be compared to mania (after melancholia). I only know from your remark in “Mourning and M”. that you miss something of that kind. And I referred to this in my comment. The increase in libido after mourning would be fully analogous to the “feast” of the manic. But I have not found this parallel from normal life in that section of “Mass Ψ” where the feast is discussed. Or have I been so struck by blindness that I am unable to see the actual reference?

So you are setting off on your travels already on 1 July. I shall start my holidays on about 10 July. First of all I am going to Bremen for a few days for my mother's 75th birthday, then we want to go to St Anton on the Arlberg. I am trying to compensate for the quite high prices by the fact that I have a patient there.

Many thanks for your news from there. At present I am analysing Mrs Powers,2 Blumgart's3 friend.

My family joins me in sending cordial greetings to you and your whole house,

Yours,

Karl Abraham

1. Abraham, 1922[79] or 1922[80].

2. Margaret Powers, American psychoanalyst, in analysis with Abraham since early April (circular letter, 15 April 1922, BL).

3. Leonard Blumgart [1880–?], M.D. 1903 Columbia, psychiatrist, in analysis with Freud until the middle of February 1922 (5 February 1922, Freud & Jones, 1993: p. 458).

411F

Vienna

28 May 19221

Dear Friend,

Still with Eitingon's assistance, I have realized to my amusement that I completely misunderstood you through no fault of yours. You were looking for a normal example of the transition mel.[ancholia]/ mania, and I was thinking of the explanation of the mechanism! Many apologies!

Cordially yours,

Freud

1. Postcard.

412A

St Anton am Arlberg, Hotel Post1

3 August 1922

Dear Professor, we have been here for a fortnight and are thoroughly enjoying our stay in the mountains, in spite of very uncertain weather. Mountaineering, a passion that I had long ago been weaned from, has taken hold of me again, and my son is proving a good companion on these excursions. I have not heard from you for a long time but hope you and yours are well. I am in lively contact with Jones and Eitingon, and yesterday revised the programme for the Congress. Could you not let me know what the “undisclosed” subject of your paper is going to be? I am starting to prepare my own paper2 today. With cordial greetings and good wishes for your holiday to all of you from all of us,

Yours,

Karl Abraham

1. Picture postcard, addressed to Bad Gastein, forwarded to Berchtesgaden.

2. In Berlin, at the last Psychoanalytic Congress Freud ever attended, he gave a short paper on Some Remarks on the Unconscious (1922f), foreshadowing the contents of The Ego and the Id. Abraham spoke about manic-depressive states (1922[81]). Ernest Jones was re-elected president of the IPA.

413A

Berlin-Grünewald

22 October 1922

Dear Professor,

Since the Congress I have given no sign of life, and as I now have various reasons for writing, I am breaking my silence today. I hope you and yours are all well. Last Sunday Oliver accompanied us on an excursion. I am glad to be able to say that I find him definitely changed for the better.1 All is well with us, only my daughter is struggling a little with the transference at the beginning of her analysis with van Ophuijsen. But I have the impression that Ophuijsen is handling the matter in a very nice and sensitive way. The circular letter reports on everything else that is going on here, so I can restrict myself to personal news, i.e. I can report to you about a few patients.

Almost a year ago your relative Gustav Brecher consulted me on your advice. The Ψα had to be postponed for various reasons. I wrote to him recently that I now had time for him. I received the reply that he has to deny himself the Ψα for financial reasons. Well, there is nothing to be done.

The American Dr Bibby has arrived. Intellectually, and in other ways too, he is better than most of his fellow countrymen, but dubious with regard to staying power and prognosis.

A former patient of yours, Cyrill Strauss from Frankfurt, whom you recommended to come to me or, if I could not take him, to Alexander, was here eight days ago. I had to put him off for a little. He wrote to me yesterday that he was not well; he wanted to start treatment at once, and was ready to go to Alexander if necessary. That is how we shall have to do it.

Today I had a letter from a Dr Tauss from Wittenberg, to whom you had also given my address. He is coming here soon for a consultation. Another similar enquiry came recently, which I cannot remember at the moment. So, many thanks for kindly thinking of me!

Róheim's lectures,2 which finish this week, were very stimulating for me. It is sad that nothing can be done for him to make his existence stable.

In a few days I am sending Rank the promised manuscript (anal character)3; I hope it contains a few useful new things. Then the paper for the Congress in an extended form will follow as soon as possible. In addition I have made a few more new discoveries on the subject of man.[ia]-depr.[ession].

Our circle here has been pleasantly enriched this winter with Ophuijsen and Radó.4 The latter has stayed here after the Congress and in the meantime is doing a few teaching analyses and waiting until I have an hour free for him. This afternoon we had a very pleasant circle in our house, including Delgado. He will also come to Vienna in a short time, and would like to join the group there, so as to be able, as a member of the International Association, to set up the South American group. He is well-instructed, very modest and likeable.

With the most cordial greetings to you, dear Professor, and yours.

Yours,

Karl Abraham

So as not to add to your correspondence, I should like to emphasize that this letter needs no answer.

1 Oliver was in analysis with Franz Alexander.

Franz Alexander [1891–1964], M.D., of Budapest. After studying medicine in Göttingen, he went to Berlin [1920–1930], where he was the first to complete a standardized psychoanalytic training. In 1930, he was invited to Chicago (professor at the University of Chicago Department of Medicine, founder of the Chicago Institute of Psychoanalysis); 1938 professor at the University of Illinois, 1956 director of the psychiatric research department at the Mount Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles. Alexander was a key figure of American psychoanalysis—particularly noted for his interest in a rapprochement between psychoanalysis, academia, and the sciences, and for his works on criminology, cultural phenomena, psychosomatics, and psychotherapeutic technique.

2 “In the month of October, Dr G. Róheim of Budapest gave six talks on ‘Psychoanalysis and Ethnology’ at the polyclinic” (Zeitschrift, 1922, 8: 528).

Géza Róheim [1891–1953], founder of psychoanalytic anthropology, creator of the ontogenetic culture theory. After analyses with Ferenczi and Vilma Kovács he became a training analyst in the Hungarian Society. In 1921 he received the Freud Prize (see Freud 1919c) for applied psychoanalysis. In 1928, with financial support from Marie Bonaparte, he undertook a research trip to central Australia and Melanesia in order to gather data there which would counter Malinowski's objections to the universality of the Oedipus complex. In 1938 Róheim fled to the United States and became active as an analyst in New York.

3. Abraham, 1921[70].

4. Sándor Radó [1890–1972], lawyer and physician; first secretary of the Hungarian Society [1913]. In Berlin he underwent analysis with Abraham and became a member of the Education Committee of the Institute. In 1924 he became chief editor of the Zeitschrift, and in 1927 of Imago. In 1931 he was invited by Brill to set up an institute in New York modelled on the one in Berlin. He went more and more his own way, left the New York Society, and organized his own analytic institute at Columbia University, which was finally recognized by the American Psychoanalytic Association. Radó represented a behaviourist view within psychoanalysis; he is especially well known for his works on toxicomania. (See Roazen & Swerdloff, 1995.)

414F

Vienna1

11 December 1922

Dear Friend,

Thank you very much for the newspaper cutting.2 Naturally I am following this piece of news with eager interest. But it will be months before we hear any more about it. A pity we can have nothing of it, not even see it. Such important things and so tangible, no ass may dare to contest such discoveries.

Cordially yours,

Freud

1. Postcard.

2. Missing; about the discovery, by the British archaeologist Howard Carter [1873–1939], of the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamen (see letter 417A, 21 February 1923).

415F

Vienna IX, Berggasse 19

26 December 1922

Dear Friend,

I have received the drawing1 that is supposed to show your head. It is hideous.

I know what an excellent person you are. It shocks me all the more that such an insignificant shadow on your character as your tolerance or sympathy for modern “art” should have to be punished so cruelly. I hear from Lampl2 that the artist has said that that is how he sees you! People like him should have the smallest possible access to analytic circles, for they are illustrations, only too undesirable, of Adler's thesis that it is precisely people with severe innate defects of vision who become painters and draughtsmen.

Let me forget this portrait, when I wish you and your dear family the finest and best for 1923.

Cordially yours,

Freud

1. A lithograph by the Hungarian deaf-mute artist Lajos Tihanyi.

2. Hans Lampl [1889–1958], M.D., a schoolmate and friend of Martin Freud's. From 1921 on in Berlin, where he underwent analytic training with Hanns Sachs and later with Helene Deutsch. Associate Member [1926] and Member [1930] of the German Society. In 1933 he and his wife returned to Vienna, and in 1938 they emigrated to Holland. (Cf. Mühlleitner, 1992: pp. 188–201.)