CHAPTER I

Negroes and Negroids

It is generally recognized today that no scientific definition of race is possible. Differences, and striking differences, there are between men and groups of men, but so far as these differences are physical and measurable they fade into each other so insensibly that we can only indicate the main divisions in broad outline. Of the psychological and mental differences which exist between individuals and groups, we have as yet only tentative measurements and limited studies; these are not sufficient to divide mankind into definite groups nor to indicate the connection between physical and mental traits. Especially is it difficult to say how far race is determined by a group of inherited characteristics and how far by environment and amalgamation.

Race would seem to be a dynamic and not a static conception, and the typical races are continually changing and developing, amalgamating and differentiating. In this book, then, we are studying the history of the darker part of the human family, which is separated from the rest of mankind by no absolute physical line and no definite mental characteristics, but which nevertheless forms, as a mass, a series of social groups more or less distinct in history, appearance, and in cultural gift and accomplishment.

Skin color in the past has been the conventional criterion by which we divided the main masses of mankind. To this is usually added hair form, although the two criteria do not entirely correspond. If we add to these two criteria any third measurement we are more at sea: long-headed people may be found among white, black and brown; and broad-headed people are of all colors and sorts of hair. Facial measurements are not only difficult to standardize but even more difficult to co-ordinate with other human characteristics.

Moreover, many of these physical distinctions depend obviously on climate, diet and environment, and are of no intrinsic significance unless they indicate lines of evolution and deeper physical, mental and social differences. Whatever men may believe concerning this—and there is a mass of passionate and dogmatic belief—there is no clear scientific proof. The most we can say today is that there appear to be three types or stocks of man, judging mainly by color and hair: the Caucasian with light skin and straight or wavy hair; the Negroid with dark skin and more or less close-curled hair; and the Mongoloid with sallow or yellow skin and straight hair.

It is not possible absolutely to delimit these three stocks of men. They fade gradually into each other and of course we might so subdivide men as to make five or more main stocks. Assuming three main stocks, we have Africa as the main home of the Negroids, although they are also represented in southern Asia and the Melanesian Islands. They are characterized by dark skins and more or less closely curled hair. Many of them are broad-headed but perhaps most of them are long-headed. They vary in height from the tallest of men in certain parts of the Sudan to the shortest among the Pygmies. They show prognathism to an undetermined extent.

There has been a tendency to try to pick out among the different stocks some ideal which characterizes the stock in its purest form. Two methods are prevalent: one, to characterize as the “pure” representative of the stock, that which varies most widely from the other ideal stocks; that is, the pure Caucasic would be represented by blond and blue-eyed Scandinavians; the pure Mongoloids by yellow, slant-eyed, straight-haired Chinese; and the pure Negro by those of darkest skin and crispest hair, together with certain extreme facial and cranial forms. There is no reason to believe that these extreme variations from the normal examples of the stocks of men represent anything racially pure or indeed anything more than local variation due primarily to climate, environment and social factors. Another method would seem much more rational and that is to regard the average representatives of the stocks as normal.

What relation is there between the black natives of Australia, India and the Melanesian Islands and those of Africa? We do not know. Perhaps there is no relation at all; simply the fact that they have been exposed to similar climatic and environmental influences. On the other hand, there may have been a continent like Lemuria between Africa and Australia from which the Negroids dispersed to both the continents and to Asia; or beginning in Asia black peoples may have wandered west; or beginning in Africa they may have migrated east. All this is pure guesswork.

A reasonable but of course unproven and perhaps unprovable thesis is that humankind in Africa started from the Great Lakes, developed down the Nile Valley and spread around the shores of the Mediterranean, forming thus the basis of both African and European peoples.

The Grimaldi Negroids, discovered in the Principality of Monaco on the French-Italian frontier in 1901, have been regarded as the earliest representatives of homo sapiens yet found in Europe. Creditable opinion is that they belong to a race of emigrants from Africa and that it was they who first established the great Aurignacian culture in Europe. It is possible to believe that the type which they represent may have been ancestral to the famous Cro-Magnon Race—a race marked in many instances by definite Negroid characters and which dominated Europe during the later phase of the Aurignacian Age.

Perhaps, too, if we think of Africa as the center of all human development, another branch went into Asia, developing into the Mongoloid peoples and the Negroid peoples of southern Asia and Oceanica. The basic Indian culture, once attributed to conquering and invading “Aryans,” is now considered by most students as the product of the dark substratum of the Indian stock.

There is evidence of ancient Negro blood on the shores of the Mediterranean, along the Tigris-Euphrates and the Ganges. These earliest of cultures were crude and primitive, but they represented the highest attainment of mankind after tens of thousands of years in unawakened savagery.

It is reasonable, according to fact and historic usage, to include under the word “Negro” the darker peoples of Africa characterized by a brown skin, curled hair, some tendency to a development of the maxillary parts of the face, and a dolichocephalic head. This type is not fixed nor definite. The color varies widely; it is never black, as some say, and it becomes often light brown or yellow. The hair varies from curly to a crisp mass, and the facial angle and cranial form show wide variation.

The color of this variety of man, as the color of other varieties, is due to climate. Conditions of heat, cold, and moisture, working for thousands of years through the skin and other organs, have given men their differences of color. This color pigment is a protection against sunlight and consequently varies with the intensity of the sunlight. Thus in Africa we find the blackest of men in the fierce sunlight of the desert, red Pygmies in the forest, and yellow Bushmen on the cooler southern plateau.

Next to the color, the hair is the most distinguishing characteristic of the Negro, but the two characteristics do not vary with each other. Some of the blackest of the Negroes have curly rather than woolly hair, while the crispest, most closely curled hair is found among the yellow Hottentots and the Bushmen. The difference between the hair of the lighter and darker races is mainly one of degree, not of kind, and can easily be measured. The elliptical cross-section of the Negro’s hair causes it to curl more or less tightly.

It is impossible in Africa as elsewhere to fix with any certainty the limits of racial variation due to heredity, to climate and to intermingling. In the past, when scientists assumed one distinct Negro type, every variation from that type was interpreted as meaning mixture of blood. Today we recognize a broader normal African type which, as Palgrave says, may best be studied “among the statues of the Egyptian rooms of the British Museum; the large gentle eye, the full but not over-protruding lips, the rounded contour, and the good-natured, easy, sensuous expression. This is the genuine African model.” To this race Africa in the main and parts of Asia have belonged since prehistoric times.

Assuming prehistoric man, whether of African or Asiatic genesis, as having developed in historic times into three main stocks, we find all these stocks represented in Africa and for the most part inextricably intermingled. The intercourse of Africa with Arabia and other parts of Asia has been so close and long-continued that it is impossible today entirely to disentangle the blood relationships. Semites in early and later times came to Africa across the Red Sea. The Phoenicians came along the northern coasts a thousand years before Christ and began settlements which culminated in Carthage and extended down the Atlantic shores of North Africa nearly to the Gulf of Guinea. Negro blood certainly appears in strong strain among the Semites; and the obvious mulatto groups in Africa, arising from ancient and modern mingling of Semite and Negro, have given rise to the term “Hamite,” under cover of which millions of Negroids, some of them the blackest of men, have been characteristically transferred to the “white” race by some eager scientists. A “Hamite” is simply a mulatto of ancient Negro and Semitic blood.

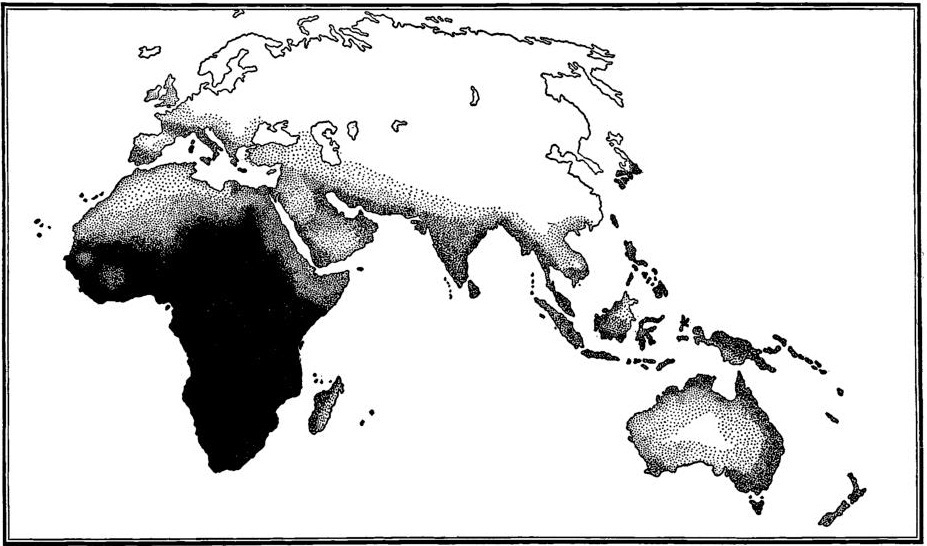

ANCIENT DISTRIBUTION OF NEGRO AND NEGROID RACES. IN THE OLD WORLD

Today we have Negroid populations in Africa which we may study under certain types. It would be impossible in limited space to name all of the at least five hundred main tribal units, which could be expanded almost indefinitely. Grouping of these tribes by physical, social or psychological measurement is impossible for lack of scientific data on any adequate or dependable scale. Cultural division is more important and possible.

One grouping follows Herskovits and is geographical and cultural: One, the Hottentot area in Southwest Africa. The Hottentots are perhaps the result of a mixture between the Bushmen and taller northern Negro tribes. There are comparatively few of them left; most of them have been absorbed into the Dutch and East Indian population. They are herdsmen originally clothed in skins and originally polygamous.

Two, the Bushmen in South Central Africa; here is a poor material culture with flowering of art and folklore, representing a very early stratum of African cultural life, with hunting as the chief occupation. The Bushman is short but not a Pygmy; his skin is yellow or yellowish-brown; his hair, sparse and closely curled; he is a hunter and lives in small bands of fifty to a hundred people; he is characterized by his rock paintings; he wears little clothing and is usually monogamous. There are also in Central Africa, the Pygmies, an interesting remains of a human group of which we know little. They are hunters and trappers and live in the thick forest. They perhaps represent the earliest African population and were known to the ancient world. They are reddish or brown in color with crisp hair.

Three, the East African cattle area, extending from the Nile Valley along the Great Lakes into South Africa; cattle occupy the most important place in the life of the people, but with this is an agricultural culture; the area of the tsetse fly breaks this culture in the center near the Great Lakes; ironworking and wood-working are pursued; the Bantu tongues are spoken in the south and the Nilotic tongues north of the lakes. A branch of this culture is found on the southwest coast.

Four, the Congo area, noted by the absence of cattle on account of the tsetse fly. It is predominantly agricultural; the secret society is important; political organization and markets occur, together with craft guilds. A branch of this Congo area can be found on the coast north of the Gulf of Guinea, in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Here is more complex political and social organization, distinctive art and larger domestic animals. These West African and Congo Negroes furnished the main mass of American Negroes.

Five, the East Horn includes such tribes as the Galla and Somali and modern Abyssinians. They are Negroids with more or less Semitic blood.

Six, the Eastern Sudan from Lake Chad to the Nile Valley and between the Sahara and the Congo. The people are mainly Negro nomads converted to Islam and organized about their live stock.

Seven, the Western Sudan, the battle ground of Mohammedanism and aboriginal religions. This is the area of great kingdoms and the flowering of political organization not unlike that of the Middle Ages in Europe. The economic life consists of herding, agriculture, manufacture and trade; the art is famous.

Eight, this section includes the desert with Mohammedan, Berber and Negroid nomads engaged in trade, camel and horse breeding.

Nine, Egypt with Arabian and some Negro blood and the Negroid Sudan.

Coming now to specific African tribes, we may attempt some general description of the various inhabitants of Africa, although the available knowledge for some regions is vague. A line drawn from the mouth of the Senegal River to Khartoum and through Abyssinia divides the Negroids of Africa into two closely related but fairly discernible parts; north of the line are peoples of mixed Negroid, Caucasic and Asiatic elements. In the extreme north Caucasians predominate among the Berbers, but fade decidedly into the Negroids after leaving the coast. Negroids are found east of Tripoli between the Sahara and the Mediterranean and evidently have lived there for a long time. Some of them resemble the ancient Egyptian stock: short, dark, long-headed people; and the same type can be found along the northern shores of the Mediterranean. The veiled Tuareg are of mixed blood but very largely Negroid. The Tibu merge into the Negroids of the central Sudan. The Fulani, spread over the western Sudan and Upper Senegal, are red-brown Negroids in part and in part Berber mulattoes. Their language is Negro.

Throughout Africa are many Arabs, but usually they are dark-skinned, if not black and Negroid, with close-curled hair. The term is applied to any person professing Islam with little reference to his blood. The conquest of Egypt by the Arabs in the seventh century brought few actual Arabian invaders to the Nile Valley. On the other hand, the invasion of the eleventh century brought a considerable number to the Sudan. There are numbers of Arabian tribes now: those to the north and east have predominant Caucasic blood and those to the west and south predominant Negro blood. In modern Egypt there is considerable Negro as well as Arab blood.

South of the Senegal-Khartoum line, we find to the west, the Sudanic and Guinea Negroes whom we can divide today only by language. They are tall and black with close-curled hair, often with broad noses and sometimes with prognathism. They build gable-roofed huts, use drums and the West African harp and are clothed in bark clothing and palm fiber. They organize secret societies and use masks, carve wood and make baskets. They are agriculturists but do not use cattle except north of the forest. They are especially the artists of Africa, working in ivory, wood and bronze. Their secret societies are primarily mutual benefit groups sometimes based on occupational guilds.

Among these people may be differentiated the Wolofs and the Serer between the Senegal and Gambia Rivers; then the Tukolors and the Mandingoes. The Wolofs are tall and black and divided into castes; the Mandingoes are tall and slender and lighter in color. All are agriculturists and many of them Mohammedans. The Songhai are tall, long-headed and brown. Perhaps there are two million of them today. The Mossi are widespread in West Africa and untouched by Mohammedanism. Their government is intricate and they are agriculturists.

In the central Sudan, east of the Niger, nearly all the tribes are Mohammedans and their political systems have been disintegrated by state building and conquest. They are the people of Kanem and of Bornu and the Bagirmi around Lake Chad. They are tall, broad-nosed and long-headed black people.

Farther south and along the coast, are found the Kru, numbering about 40,000 and noted as seamen. On the Guinea coast are the Ashanti and allied peoples; the Ewe-speaking peoples and those of Dahomey, and especially the notable Yoruba. They have an advanced political organization and highly organized states such as Ashanti, Benin, Dahomey and Oyo. The Ashanti are of moderate stature and long-headed, numbering perhaps a quarter of a million people. Dahomey long had human sacrifice and a corps of women soldiers. They are tall and long-headed people, some of them the tallest in the world. Many are noted for their high social organization.

Across the Sudan from the Niger to the Nile stretch millions of black hillmen, some pagan and some Mohammedan, with a history of a succession of great states. The Hausa form a mixture of various tribes, united by language, and number more than five million. They are united in the Mohammedan emirates of Sokoto, Katsina, Kano, Zaria and others. They are farmers, traders and artisans and in the Middle Ages were divided into seven powerful states. They are tall, black and long-headed but usually not prognathic nor broad-nosed.

In this part of Africa are large numbers of pagan groups like the Nupe and the Jukur whose king is regarded as semi-divine. Farther to the east are the tall Nuba in the hills of southern Kordofan and the peoples of Darfur whose sultanate ended only with the World War. East of Kordofan are the Fung and other tribes, some of whom have mixtures of Asiatic blood.

In this Nile Valley are the Beja, the Nubians, the Galla, the Somali and the Abyssinians. The early Egyptians up the Nile Valley are probably represented today by the Beja. The shorter and more delicate pre-dynastic Egyptians were eventually mixed with stronger, taller and darker people from the upper Nile Valley and it was this sort of Egyptian that developed the highest civilization; from these, modern Egyptians have descended with dark color and a considerable proportion of broad noses and crisp hair.

Nubians are the descendants of those whom the Egyptians regarded as pure Negroes and whom they endeavored to keep above the first cataract. The Nubians are of medium height and long-headed. They have a long history going back two or three thousand years before Christ and closely intertwined with that of Egypt. Between the Sudan and Kenya are Eritrea, Abyssinia and Somaliland. The Negroids here have been mixed more or less with Semitic blood, especially toward the east and in Abyssinia, where Asiatic and Negroid languages are spoken. In Abyssinia the main mass are Semitic mulattoes; beside these are the black Jews known as Falashas; the Galla, tall brown people; the Somali, tall black people; and the Danakil, thin black curly-haired folk. All through this part of Africa are many small, unclassified tribes representing various kinds of artisans with some relationships to the Pygmies and Bushmen.

The peoples of East Africa and East Central Africa have often been given the name of Hamites. They represent the successive invasions from southern Arabia and the Horn of Africa spreading among various African peoples. Among them are the Masai and Nandi, the Suk and others. They are tall, slender and longheaded and brown or black in color. Many of them are nomadic herdsmen. Their cattle have exaggerated importance and are the center of their life and social organization. The medicine man plays a large part. There are also the Bari- and the Lotuko-speaking people, divided into totemic clans.

Between the Nile and the Congo are numbers of people often called Nilotic, like the Bongo, the Azande and the Mangbettu. The Azande are a confederation of tribes forming something like a nation. This confederation was pushing east and west at the time of the forming of the Belgian Congo. They are of varied physical characteristics and are organized in clans.

The so-called Nilotic peoples extend from some two hundred miles south of Khartoum to Lake Kiogo in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. Among them are the Shilluk, the Dinka and the Nuer. They are all tall, black, long-headed people. Cannibalism and human sacrifice are unknown and they are herdsmen and hunters with varied social organization. The Shilluk are united into a strong nation with a king and have a long cultural history.

The Bantu are a mingled mass of tribes in central and southern Africa, united by the type of language which they speak. They probably originated near the Great Lakes. East and south there is some infiltration of Asiatic blood. They may be divided into southern, western and eastern Bantu. The southern Bantu are south of the Zambesi River, covering Southern Rhodesia, the southern half of Portuguese East Africa, the Union of South Africa, Southwest Africa and Bechuanaland. The eastern Bantu stretch through Kenya, Tanganyika, Northern Rhodesia, Nyasaland and Portuguese East Africa north of the Zambesi. The western Bantu stretch from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic and up to French West Africa.

The southern Bantu form the largest group, divided into numbers of tribes. It includes the Shona people toward the north and toward the east the Zulu-Xosa which include the Xosa, the Tembu, the Pondo, etc., the Matabele and others. In the center are the Bechuana, the Bamangwato and the Basuto. Toward the west are the Herero-Ovambo. They are tall graceful people with Negro hair and dark chocolate tinge.

The Basutos consist of various tribes welded together by Moshesh into a nation. The Zulus consist of a hundred small separate tribes united by Chaka at the end of the eighteenth century. The history of Southeast Africa is one of wars, separations, migrations, etc., out of which various tribes emerged. The tribes vary in size from a few hundred to a couple of thousand and in some cases larger. The Bakwena number 11,000; the Bamangwato 60,000; the Ovambo 65,000; the Swazi 110,000 and the Basuto nearly a half million. They live in small households which unite into villages of some five to fifty households. The southern Bantus are patrilineal; the western largely matrilineal. They keep cattle and raise crops. Ancestor worship is strong.

The western Bantu include French Equatorial Africa and the Congo Free State together with Portuguese East Africa north of Zambesi. This is the tropical rain forest of Africa and has had many highly organized kingdoms like the Kingdom of the Kongo, Balunda and later the Bushongo Empire. There are some one hundred and fifty tribes in this territory. Among these are the Barotse, the Luba-Wenda tribes, the Basongo; the Bakongo and Bushongo groups who are noted for their wood carving; the Bateke; and farther north the Pangwe or Fang. The eastern Bantu include the peoples of Uganda who formed at one time the Kitwara empire. The Baganda have a semi-feudal organization. They form a part of Uganda, where there is evidence of invading warriors among agricultural people. The Baganda are tall stout men dark in color with Negroid hair. Other lake tribes include the Wanyamwezi.

The eastern Bantu fall into two main parts: the Akamba and Kikuyu toward the north and numbers of tribes with totemic clans and age groups. The Kikuyu have large plantations, cattle and goats. In the east, among the eastern Bantu, the Swahili are important because their language has become the chief medium of communication over all East Africa. It is a Bantu language with Arabic and Portuguese words. The tribe itself is mixed with many elements.

The general physical contour of Africa has been likened to an inverted plate with one or more rows of mountains at the edge and a low coastal belt. In the south the central plateau is three thousand or more feet above the sea, while in the north it is a little over one thousand feet. Thus two main divisions of the continent are easily distinguished: the broad northern rectangle, reaching down as far as the Gulf of Guinea and Cape Guardafui, with seven million square miles; and the peninsula which tapers toward the south, with five million square miles. More than any other land, Africa lies in the tropics, with a warm, dry climate, save in the central Congo region, where rain at all seasons brings tropical luxuriance.

If the history of Africa is unusual, its strangeness is due in no small degree to the physical peculiarities of the continent. With three times the area of Europe it has a coast line a fifth shorter. Like Europe it is a peninsula of Asia, curving southwestward around the Indian Sea. It has few gulfs, bays, capes, or islands. Even the rivers, though large and long, are not means of communication with the outer world, because from the central high plateau they plunge in rapids and cataracts to the narrow coastlands and the sea.

Two physical facts underlie all African history: the peculiar in accessibility of the continent to peoples from without, which made it so easily possible for the great human drama played here to hide itself from the ears and eyes of other worlds; and, on the other hand, the absence of interior barriers—the great stretch of that central plateau which placed practically every budding center of culture at the mercy of barbarism, sweeping a thousand miles, with no Alps or Himalayas or Appalachians to hinder, although the Congo forest was a partial barrier.

With this peculiarly uninviting coast line and the difficulties of interior segregation must be considered the climate of Africa. While there is much diversity and many salubrious tracts along with vast barren wastes, yet, as Sir Harry Johnston well remarks, “Africa is the chief stronghold of the real Devil—the reactionary forces of Nature hostile to the uprise of Humanity. Here Beelzebub, King of the Flies, marshals his vermiform and arthropod hosts—insects, ticks, and nematode worms—which more than in other continents (excepting Negroid Asia) convey to the skin, veins, intestines, and spinal marrow of men and other vertebrates, the micro-organisms which cause deadly, disfiguring, or debilitating diseases, or themselves create the morbid condition of the persecuted human being, beast, bird, reptile, frog, or fish.”1 The inhabitants of this land have had a sheer fight for physical survival comparable with that in no other great continent, and this must not be forgotten when we consider their history.

Four great rivers and many lesser streams water the continent. The greatest is the Congo in the center, with its vast curving and endless branches; then the Nile, draining the cluster of the Great Lakes and flowing northward “like some grave, mighty thought, threading a dream”; the Niger in the northwest, watering the Sudan below the Sahara; and, finally, the Zambesi, with its greater Niagara in the southeast. Even these waters leave room for deserts both south and north, but the greater ones are the three million square miles of sand wastes in the north.

It may well be that Africa rather than Asia was the birthplace of the human family and ancient Negro blood the basis of the blood of all men. Negro races were among the first who made and used tools, developed systematic religion, pursued art, domesticated animals and smelted metal, especially iron. The subsequent development of the Negro race was affected by physical changes in Africa: the Sahara and Lybian deserts, once fertile plains, were desiccated, forcing Negroes to migrate. Many of the peoples and much of the culture of ancient Egypt originated in Equatorial Africa. In the mythology of ancient Greece many Negroes play parts—Memnon, Eurybates, Cephus, Cassiopeia and Andromeda. During the Middle Ages in the western Sudan, Negro kingdoms and empires were organized with as high culture as many of the contemporary states in Europe. The increasing desiccation of north and south Africa, the introduction of Christianity and Mohammedanism and the establishment of the Arab and European slave trade overthrew these Negro states and largely ruined their culture.

Africa is at once the most romantic and the most tragic of continents. Its very names reveal its mystery and wide-reaching influence. It is the “Ethiopia” of the Greek, the “Kush” and “Punt” of the Egyptian, and the Arabian “Land of the Blacks.” To modern Europe it is the “Dark Continent” and “Land of Contrasts”; in literature it is the seat of the Sphinx and the lotus eaters, the home of the dwarfs, gnomes, and pixies, and the refuge of the gods; in commerce it is the slave mart and the source of ivory, ebony, rubber, gold, and diamonds. What other continent can rival in interest this Ancient of Days?