CHAPTER III

The Niger and the Desert

The Arabian expression “Bilad es Sudan” (Land of the Blacks) was applied to the whole region south of the Sahara, from the Atlantic to the Nile. It is a territory some thirty-five hundred miles by six hundred miles, containing two million square miles, and has today a population of perhaps eighty million. It is thus two-thirds the size of the United States and about as thickly settled. In the western Sudan the Niger plays the same role as the Nile in the east. In this chapter we follow the history of the Niger.

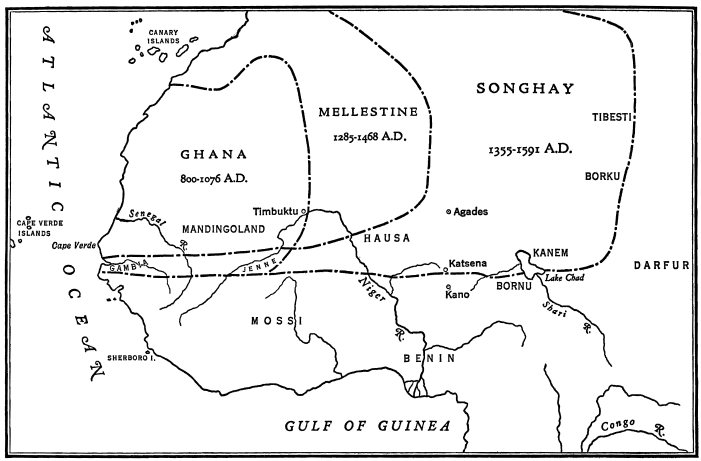

The history of this part of Africa was probably something as follows: primitive man from the Great Lakes spread in the Nile Valley, and wandered westward to the Niger. Herodotus tells of certain youths who penetrated the desert to the Niger and found there a city of black dwarfs. Succeeding migrations of Negroes pushed the dwarfs gradually into the inhospitable forests and occupied the Sudan, pushing on to the Atlantic. Here the newcomers, curling northward, came in contact with Europeans or Berbers, or actually crossed into Europe; while to the southward the Negro came to the Gulf of Guinea and the thick forests of the Congo Valley. Indigenous civilizations arose on the west coast in Yoruba and Benin, and contacts of these with the Berbers in the desert, and Semites from Arabia and from the east gave rise to centers of Negro culture in the Sudan, at Ghana and Melle and in Songhay; in Nupe, the Hausa states, and Bornu.

We know that Egyptian Pharaohs in several cases ventured into the western Sudan and Egyptian influences are distinctly traceable. Greek and Byzantine culture and Phoenician and Carthaginian trade also penetrated, while Islam had wide influence. Behind all these influences, however, stood from the first an indigenous Negro culture. The stone figures of Sherbro, the megaliths of Gambia, the art and industry of the West Coast are all too deep and original evidences of civilization to be merely importations from abroad.

Nor was the Sudan the inert recipient of foreign influence when it came. According to credible legend, the “Great King” at Byzantium imported glass, tin, silver, bronze, cut stones, and other treasure from the Sudan. Embassies were sent and states like Nupe recognized the suzerainty of the Byzantine emperor. The people of Nupe especially were filled with pride when the Byzantine people learned certain kinds of work in bronze and glass from them, and this intercourse was only interrupted by the Mohammedan invasion.

To this ancient culture, modified somewhat by Byzantine and Christian influences, came Islam and the Arabs. They swept in as a conquering army in the seventh century but were comparatively few in actual numbers until the eleventh century, when there was a large Arab immigration. In the seventh century the Arabs conquered North Africa from the Red Sea to the Atlantic. The Berber Mohammedans, led by the Arabs, entered Spain in the eighth century and overthrew the Visigoths. In 718 A.D. they crossed the Pyrenees and met Charles Martel at Poitiers. The invaders, repulsed, turned back and settled in Spain, occupying it without much attempt to proselyte. But in time the conflict for the control of the Mohammedan world left Spain in anarchy.

In 758 there arrived in Spain a Prince of Omayyads, Abdurrahman, who after thirty years of fighting founded an independent government which in the tenth century became the Caliphate of Kordova. The power was based on his army of Negro and Slavonian Christian slaves. Abdurrahman III, 912–961, established a magnificent court and restored order. His son gave protection to writers and thinkers. His power passed into the hands of a mulatto known as Almansur, who kept order with his army of Berbers and Negroes, making fifty invasions into Christian territory. He died in 1002 and in a few years through the revolt of the army the Caliphate declined and the Christians began to reconquer the country. The Mohammedans began to look to Africe for rescue.

“When the conquest of the West [by the Arabs] was completed, and merchants began to penetrate into the interior, they saw no nation of the Blacks so mighty as Ghanah, the dominions of which extended westward as far as the ocean.” In the eleventh century there was a large Arab immigration. The Berbers by that time had adopted the Arab tongue and the Mohammedan religion, and Mohammedanism had spread slowly southward across the Sahara; while in east Africa, Arabs, Persians and Indians had planted commercial colonies on the coast.

About 1000–1200 A.D. the situation was this: Ghana was on the edge of the desert in the north; Mandingoland was between the Niger and the Senegal in the south and the western Sahara, the Wolofs were in the west on the Senegal; and the Songhay on the Niger in the center. The Mohammedans came chiefly as traders and found a trade already established. Here and there in the great cities were districts set aside for these new merchants, and the Mohammedans gave freauent evidence of their resnect for these black nations.

Islam did not found new states, but modified and united Negro states already ancient; it did not initiate new commerce, but developed a widespread trade already established. It is, as Frobenius says, “easily proved from chronicles written in Arabic that Islam was effective in fact only as a fertilizer and stimulant. The essential point is the resuscitative and invigorative concentration of Negro power in the service of a new era and a Moslem propaganda, as well as the reaction thereby produced.”1 Later in the eleventh century Arabs penetrated the Sudan and Central Africa from the east, filtering through the Negro tribes of Darfur, Kanem, and neighboring regions.

In the twelfth century a learned Negro poet resided at Seville, and Sidjilmessa, the last town in Lower Morocco toward the desert, was founded in 757 by a Negro who ruled over the Berber inhabitants. Indeed, many towns in the Sudan and the desert were thus ruled, and felt no incongruity in this arrangement. They say, to be sure, that the Moors destroyed Audoghast because it paid tribute to the black town of Ghana, but this was because the town was heathen and not because it was black. On the other hand, there is a story that a Berber king overthrew one of the cities of the Sudan and all the black women committed suicide, being too proud to allow themselves to fall into the hands of white men.

In the west the Moslems first came into touch with the Negro kingdom of Ghana. Here large quantities of gold were gathered in early days. The history of Ghana goes back at least to the fourth century. It was probably founded by Berbers but eventually passed into the control of the black Sarakolle peoples. In the ninth and tenth centuries it was flourishing but fell before the proselyting Almoravides and eventually passed under the control of Melle. Its chief city was Kumbi‒Kumbi, the ruins of which have been identified. It had prosperous agriculture and its later decline was due in part to the encroachment of the desert. The surrounding country was inhabited by the Bafur Negroes, who formed the Songhay toward the east, and Serers and the Wangara in the center. To the Wangara belong the Mandingoes who founded Melle. West of Ghana a mixture of Serers and Berbers formed the mulatto Fulani peoples. The black kings of Ghana eventually extended their rule over the Berber city of Audhoghast and the veiled tribes of the desert.

At Ghana we are told that there were forty‒four white rulers, half coming before the Hegira and half after it. Then the power passed to black Sarakolles who were Negroes with some Semitic blood. By the middle of the eleventh century Ghana was the principal kingdom in the western Sudan. Already the town had a native and a Mussulman quarter, and was built of wood and stone with surrounding gardens. The king had an army of two hundred thousand and the wealth of the country was great. A century later the king had become Mohammedan in faith and had a palace with sculptures and glass windows. The great reason for this development was the desert trade. Gold, skins, ivory, kola nuts, gums, honey, wheat, and cotton were exported, and the whole Mediterranean coast traded with the Sudan.

Meantime, led by Yassine, three Berber tribes, inflamed with religious zeal, began to spread, starting from the lower Senegal and converting the black natives over a considerable territory. Audhoghast was recaptured from Ghana in the eleventh century, and reinforced by black converts, the movement spread until eventually it went into Morocco and then into Spain. Composed now of Berbers and Negroes, these fanatics shaped their course northward, and, united under the name of Al Morabitun, or Champions of the Faith, they subjugated the fertile countries on both sides of the southern Atlas, and founded, in 1073, the empire and city of Morocco.

The Al Morabitun, or Morabites, subsequently extended their plan into Spain, in the history of which country they figure under the name of Almoravides. “But long before they carried their arms into Europe, they corresponded intimately with the polished courts of Mohammedan Spain; and while they had not yet quite relinquished the desert, nor forgotten their acquaintance with the frontiers of Negro-land, they communicated their information to the inquisitive, and, for that age, well-instructed Spanish Arabs.”2 This movement invaded Spain and inflicted a decisive defeat on Alphonso VI and Zilaca in 1086 under the leadership of Yusuf. The Almoravides held the conquest until 1120 when they suffered defeat at Kutanda at the hands of the Almohades, a more bigoted religious sect, who were victorious in 1195 and held Mohammedan Spain until 1212. By 1238, however, Mohammedan Spain was reduced to the ports between Granada and Cadiz.

ANCIENT KINGDOMS OF THE SUDAN, 800-1591 A.D.

The spread of Islam in Africa was slow. Timbuktu founded, in the eleventh century, did not become Mohammedan until 1591. The Congo forest kept back the Arabs from expanding westward from the east coast, just as the Sahara kept them from expanding southward in North Africa. At the end of the eleventh century the Almoravides carried their proselyting down toward the Gulf of Guinea, attracted by the abundance of kola nuts, and founded a city on the Volta River. This city, Bego, became an important metropolis and center of commerce and propaganda. Later its inhabitants spread along the Ivory Coast, enriching themselves with commerce and intellectual development, which has continued up to the present.

In the early part of the thirteenth century the prestige of Ghana began to fall before the rising Mandingan kingdom to the west. Melle, as it was called, was founded in 1235 and formed an open door for Moslem and Moorish traders. The new kingdom, helped by its expanding trade, began to grow, and Islam slowly surrounded the older Negro culture west, north, and east. However, a compact mass of that older heathen culture, pushing itself upward from the Guinea coast, stood firmly against Islam down to the nineteenth century.

Steadily Mohammedanism triumphed in the growing states which almost encircled the protagonists of ancient Atlantic culture. Mandingan Melle eventually supplanted Ghana in prestige and power, after Ghana had been overthrown by the Soso in 1203. The territory of Melle lay southeast of Ghana and some five hundred miles north of the Gulf of Guinea. Its kings were known by the title of Mansa, and from the middle of the thirteenth century to the middle of the fourteenth, the Mellestine, as its dominion was called, was the leading power in the land of the blacks.

Melle began on the left bank of the Upper Niger, under Negro kings who reigned without interruption, save for fifteen years, from 600 to the present, and are probably the oldest reigning dynasty in the world. The Mansa, or kings of Melle, were obscure rulers until about 1050, when they were converted to Mohammedanism.

“As to the people of Mali [Melle], they surpassed the other Blacks in these countries in wealth and numbers. They extended their dominions, and conquered the Susu, as well as the kingdom of Ghanah in the vicinity of the Ocean towards the west. The Mohammedans say that the first King of Mali was Baramindanah. He performed the pilgrimage to Mekkah, and enjoined his successors to do the same.”3

Melle secured control of the trade in gold dust which Ghana had formerly monopolized. It was annexed by the Soso in 1224, but Sundiata Keita made the country independent and allied himself with neighboring Mandingo chiefs. He took Ghana and destroyed it in 1240 and developed agriculture, also the raising and wearing of cotton. Under his successor, various southern territories, including the valley of the Gambia River, were added to Melle; and from 1307 to 1332, Gongo-Mussa brought the kingdom of Melle to its highest prosperity. He made a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 which aroused great interest, and brought back with him an Arab who began a new style of architecture in the black Sudan.

“The number of people employed to carry his baggage and provisions amounted to 12,000, all dressed in tunics of figured cotton, or the silk called El-Yemeni. The Haji Tunis, interpreter of this nation in Kahirah [Cairo], said that Mansa [Gongo] Mussa brought with him to Egypt no less than 80 loads of Tibar [gold dust], each weighing 300 pounds.”4

On his return from Mecca, Gongo-Mussa found that Timbuktu had been sacked by the Mossi, but he rebuilt the town and filled the new mosque with learned blacks from the University of Fez. Gongo-Mussa reigned twenty-five years and “was distinguished by his ability and by the holiness of his life. The justice of his administration was such that the memory of it still lives.”

“Ibn Said, a writer of the thirteenth century, has enumerated thirteen nations of Blacks, extending across Africa, from Ghanah in the west, to the Boja [Beja] on the shores of the Red Sea in the east.”

The Mandingan empire at this time occupied nearly the whole of what is now French West Africa, including part of British West Africa. The rulers had close relations with the rulers of Morocco and interchanged visits. Ibn Batuta visited Melle in 1352 and testified to the excellent administration of the city, and its courtesy, prosperity and discipline. Its finances were in good condition and there was luxury and ceremony. In fine the culture of Melle at this time compared favorably with the culture of Europe. The Mellestine preserved its pre-eminence until the beginning of the fifteenth century, when the rod of Sudanese empire passed to Songhay, the largest and most famous of the black empires.

This Negro kingdom centered at Gao, where a dynasty called the Dia, or Za, remained in power on the western Niger from 690 to 1335. The known history of Songhay covers a thousand years and three dynasties, and centers in the great bend of the Niger. There were thirty kings of the First Dynasty. During the reign of one of these, the Songhay kingdom became the vassal kingdom of Melle, then at the height of its glory. In addition to this, the Mossi crossed the valley, plundered Timbuktu in 1339, and separated Jenne, the original seat of the Songhay, from the main empire. The sixteenth Songhay king was converted to Mohammedanism in 1009, and after that all the Songhay princes were Mohammedans.

Gongo-Mussa, on his capture of Timbuktu, had taken two young Songhay princes to the court of Melle to be educated in 1326. These boys when grown ran away and founded a new dynasty in Songhay, that of the Sonnis, in 1355. Seventeen of these kings reigned, the last and greatest being Sonni Ali, who ascended the throne in 1464. Melle was at this time declining, and other cities like Jenne, with its seven thousand villages, were rising, and the Tuaregs (Berbers with Negro blood) had captured Timbuktu.

Sonni Ali was a soldier and began his career with the conquest of Timbuktu in 1469. He also succeeded in capturing Jenne and attacked the Mossi and other enemies on all sides. Finally he concentrated his forces for the destruction of Melle and subdued nearly the whole empire on the west bend of the Niger. In summing up Sonni Ali’s military career the chronicle says of him, “He surpassed all his predecessors in the number and valor of his soldiery. His conquests were many and his renown extended from the rising to the setting of the sun. If it is the will of God, he will be long spoken of.”

After the death of Sonni Ali, the dynasty of the Askias ruled in Songhay from 1493 to 1591. The first one, Askia Mohammed, ruled from 1493 to 1529. Sonni Ali was a Songhay, whose mother was black and whose father, a Berber. He was succeeded by a full-blooded black, Mohammed Abou Bekr, who had been his prime minister. Mohammed was hailed as “Askia” (usurper) and is best known as Mohammed Askia. He was strictly orthodox where Ali was rather a scoffer, and an organizer where Ali was a warrior. On his pilgrimage to Mecca in 1497 there was nothing of the barbaric splendor of Gongo-Mussa, but a brilliant group of scholars and officials with a small escort of fifteen hundred soldiers and nine hundred thousand dollars in gold. He stopped and consulted with scholars and politicians, and studied matters of taxation, weights and measures, trade, religious tolerance and manners. Eventually he was made by the authorities of Mecca, Caliph of the Sudan. He returned to the Sudan in 1497.

He had a genius for selecting collaborators, and instead of forcing the peasants into the army, he recruited a professional army and encouraged farmers, artisans and merchants. He undertook a holy war against the indomitable Mossi, and finally marched against the Hausa. He subdued these cities and even imposed the rule of black men on the Berber town of Agades, a rich city of merchants and artificers with stately mansions. In fine, Askia, during his reign, conquered and consolidated an empire two thousand miles long by one thousand wide at its greatest extent—a territory as large as all Europe. The territory was divided into four vice-royalties, and the system of Melle, with its semiindependent native dynasties, was carried out. His empire extended from the Atlantic to Lake Chad and from the salt mines of Tegazza and the town of Augila in the north to the tenth degree of north latitude toward the south.

It was a six months’ journey across the empire and, it is said, “he was obeyed with as much docility on the farthest limits of the empire as he was in his own palace, and there reigned everywhere great plenty and absolute peace.” Leo Africanus described his state about 1507. He made intellectual centers at cities like Gao, Timbuktu and Jenne, where there were writers and where students from North Africa came to study. A literature developed in Timbuktu in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The University of Sankore became a center of learning in correspondence with Egypt and North Africa and had a swarm of black Sudanese students. Law, literature, grammar, geography, and surgery were studied. Askia the Great reigned thirty-six years, and his dynasty continued on the throne until after the Moorish invasion of 1591.

It was a six months’ journey across the empire and, it is said, “he was obeyed with as much docility on the farthest limits of the empire as he was in his own palace, and there reigned everywhere great plenty and absolute peace.” Leo Africanus described his state about 1507. He made intellectual centers at cities like Gao, Timbuktu and Jenne, where there were writers and where students from North Africa came to study. A literature developed in Timbuktu in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The University of Sankore became a center of learning in correspondence with Egypt and North Africa and had a swarm of black Sudanese students. Law, literature, grammar, geography, and surgery were studied. Askia the Great reigned thirty-six years, and his dynasty continued on the throne until after the Moorish invasion of 1591.

Before continuing the history of the Songhay, we may note some smaller, contemporary states. There were the Bambara south of Timbuktu, who flourished from 1660 to 1862; there were the various Fulani kingdoms from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, and the Tukolor conquest of 1776. West of Ghana, the long dwelling of Berbers with the black Serers formed eventually the Fulani people who sent forth groups to the southwest, east and southeast. In the early sixteenth century the Fulani attacked Songhay but were repulsed and took refuge northwest of the Futa-Jalon. Eventually they founded a kingdom under the so-called Deninake who maintained power from 1559 to 1776. In the Futa-Jalon, inland from French Guinea, the Soso and Fulani, together with other Negro tribes, formed a nation called the Fula, speaking the Fulani language and for the most nart Mohammedans, who built up a theocratic state.

Many smaller states were involved in this history; there was the kingdom of Diara southwest of Ghana, which lasted from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century with more or less independence, and was finally incorporated into the Songhay empire. The kingdom of the Soso southwest of Timbuktu was at first dependent upon Ghana. Then Sumangura in 1203 overwhelmed Ghana and held it for a few years, but the Soso were finally overcome by Sundiata of Melle and the state annexed. Far to the west came a revolt of Tukolor Negroes late in the eighteenth century. They triumphed over the Fulani, and under Omar extended their conquest considerably. Omar made a pilgrimage to Mecca. He was finally put to flight by the French in 1859 with the help of the mulatto French commander Paul Holle. His entire territory was annexed by the French in 1890.

The Mossi had two kingdoms founded in the eleventh and twelfth centuries among the Negroes inland from the Gulf of Guinea. They are of interest because of the type of state which they invented, and which was widely copied over Negro Africa and still persists. The main Mossi empire had four vassal kingdoms besides the kingdom of the ruler. In the ruler’s kingdom there were five provinces whose governors made up the imperial council and were the chief officers of state. Associated with the council were eleven ministers ruling the army, religion, musicians and collecting taxes. The Mossi empires were peculiar in having little or no Berber or white influence. They did not make extensive conquests, but at one time attacked Timbuktu and later resisted Sonni Ali.

Askia Mohammed of the Songhay was succeeded by descendants who nearly ruined his great country by civil wars, massacres and unfortunate military expeditions. One successor, Daoud, who reigned from 1549 to 1583, renewed agriculture and science and was closely associated with the Sultan of Morocco, but already the empire was on the decline.

Meantime great things were happening in the world beyond the desert, the ocean, and the Nile; Arabian Mohammedanism succumbed to the wild fanaticism of the Seljukian Turks. These new conquerors were not only firmly planted at the gates of Vienna, but had swept the shores of the Mediterranean and sent all Europe scouring the seas for their lost trade connections with the riches of Asia. Religious zeal, fear of conquest, and commercial greed inflamed Europe against the Mohammedans and led to the discovery of a new world, the riches of which poured first on Spain and then on England.

Oppression of the Berbers and Moors in Spain followed and in 1502 they were driven back into Africa, despoiled and humbled. Here the Spaniards followed and harassed them; and here the Turks, fighting them and the Christians, captured the Mediterranean ports and cut the Moors off permanently from Europe.

The Moors in Morocco had come to look upon the Sudan as a gold mine, and knew that the Sudan was especially dependent upon salt. In 1545 Morocco claimed the principal salt mines at Tegazza, but the reigning Askia refused to recognize the claim. When the Sultan Almansur came to the throne of Morocco, he increased the efficiency of his army by supplying it with firearms and cannon. Almansur determined to attack the Sudan. A company of 3,000 Spanish renegades with muskets, led by Judar, finally attacked the Songhay in 1590. They overthrew the Askias at the battle of Tondibi in 1591 and thereafter ruled at Timbuktu.

Askia lshak, the king, offered terms, and Judar Pasha referred them to Morocco. The Sultan, angry with his general’s delay, deposed him and sent another who crushed and treacherously murdered the king and set up a puppet. Thereafter there were two Askias, one at Timbuktu and one who maintained himself in the Hausa states to the east, which the invaders could not subdue. Anarchy reigned in Songhay. The soldiers tried to put down disorder with a high hand, drove out and murdered distinguished men of Timbuktu, and as a result let loose a riot of robbery and decadence throughout the Sudan. Pasha now succeeded pasha with revolt and misrule, until in 1612 the soldiers elected their own pasha and deliberately shut themselves up in the Sudan by cutting off approach from Morocco and the north.

Hausaland and Bornu were still open to Turkish and Mohammedan influence from the east, and the Gulf of Guinea to the slave trade from the west; but the face of the finest Negro civilization the modern world had produced, was veiled from Europe and given to the defilement of a wild horde, which Delafosse calls the “Scum of Europe.” In 1623 it is written “excesses of every kind are now committed unchecked by the soldiery,” and “the country is profoundly convulsed and oppressed.”

The Tuaregs marched down from the desert and deprived the invaders of many of the principal towns. The rest of the empire of the Songhay was by the end of the eighteenth century divided among separate chiefs, who bought supplies from the Negro peasantry and were “at once the vainest, proudest, and perhaps the most bigoted, ferocious, and intolerant of all the nations of the south.” They lived a nomadic life, plundering the Negroes. To such depths did the mighty Songhay fall.

After 1660 these Pashas, now of mixed Spanish and Negro blood, ruled at Timbuktu for 120 years. They preserved a pretense of authority by paying tribute to the black Bambara kings of Segu and also by bribing the Tuaregs. After 1780 the title of Pasha disappeared and “mayors” of Timbuktu were chosen sometimes by the Bambara, sometimes by the Tuareg, and sometimes by the Fulani. In 1894 the city was taken by Joffre, later Marshal of France.

Meanwhile, to the eastward, two powerful states had appeared. They never disputed the military supremacy of Songhay, but their industrial development was marvelous. The Hausa states were formed by seven original cities, of which Kano was the oldest and Katsina the most famous. Gober was celebrated after the sixteenth century for its cotton and leather manufacture. Kano was populous in the sixteenth century. Katsina was the center of agriculture and had military power, and Zaria was a center of commerce. In the fifteenth century these states were united under the kings of Kebbi. In 1513 the Hausa states made alliance with Askia Mohammed of Songhay, but afterward regained their independence.

Their greatest leaders, Mohammed Rimpa and Ahmadu Kesoke, arose in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. The land was subject to the Songhay, but the cities became industrious centers of smelting, weaving, and dyeing. Katsina especially, in the middle of the sixteenth century, is described as a place thirteen or fourteen miles in circumference, divided into quarters for strangers, for visitors from various states, and for the different trades and industries, as saddlers, shoemakers, dyers, etc.

The Hausa were converted to Mohammedanism about the beginning of the nineteenth century. This was accomplished by the Sheik Ousman, who extended his rule over the Hausa kingdom and Kebbi, and even invaded Bornu early in the nineteenth century. He was succeeded by Mohammed Bello, who reigned from 1815 to 1837. Mohammed Bello was a noted man of letters who composed poems and prose works in Arabic. He was succeeded by his brother and then by his son, who were harassed by continual revolts. Finally the pieces of the empire fell apart in 1904, and the capital Sokoto was occupied by the British under Lugard.

To the east of the Hausa, on both sides of Lake Chad, is a domain called Bornu in the west and Kanem in the east. The population is dispersed across immense territories and divided into a great number of tribes, some frankly Negroes and others more or less mixed with white blood. The first ruler of Bornu-Kanem was Saefe and was certainly Negro, although we do not know exactly when he lived. Toward the eleventh century under one of his successors, Mohammedanism made its first appearance. The dynasty of Saefe was overthrown by Mohammedans, whose kings took the title of Mai. The first king, ruling from 1220 to 1259, had to contend with continual revolts from the subdued peoples, so that two centuries passed in anarchy. Mai Idris I, 1352 to 1376, came to the throne when the Arab traveler, Ibn Batuta, was visiting near. At that time copper mines were in full operation and many Negro customs were evident, like the concealment of the king behind a curtain, and the use of drums with different rhythms to send messages. Under ldris III, 1573 to 1603, the empire of Bornu was at its height. It ruled over Kano and the Air, over Kanem and land south of Lake Chad. The Tunjur Negroes were in the ascendancy. Rabah attacked and conquered the country in 1893, but after his death the English made Bornu a British protectorate.

Southwest of Lake Chad, arose in 1520 a sultanate of Bagirmi, which reached its highest power in the seventeenth century. This dynasty was overthrown by the Negroid Mabas, who established Wadai to the eastward about 1640. After struggling with Bornu it was attacked by Rabah in 1893 and annexed by the French in 1896. Wadai and a number of other tribes with Arabian and Negro blood ruled in the eastern Sudan in the seventeenth centurv

Darfur and Kordofan in the eastern Sudan arose to power in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. A ruler of Kordofan was in touch with Napoleon in his Egyptian campaign late in the eighteenth century. Kordofan was occupied by the Egyptians in the nineteenth century and extended to the Nile. The southern or mountainous part of Kordofan was called Nubia, although that name is also used for the region about Dongola. The central figure of the eastern Sudan in the nineteenth century is Rabah. Rabah was the son of a Negro woman and the principal lieutenant in the army of Zobir Pasha, who was governor of the Bahr-el-Ghazal in 1875. When Zobir’s son was overthrown, Rabah took the army and began conquest northwest of the Bahr-el-Ghazal in 1878. He brought a considerable part of north central Africa under control, overthrowing the Bagirmi, Bornu, Gober and many other states around Lake Chad. In 1900 he was conquered and killed by the French after an adventure of twenty-two years.

These complicated and not yet thoroughly known phases of history have almost been forgotten in modern times. Many long regarded it as Arabian and Mohammedan history because Arabic was the lingua franca of most of these peoples. Lately, however, a clearer knowledge of the meaning and development in this part of Africa has been attained. These peoples were not Arabs. They were Negroes with some infiltration of Arabian blood. They were not all Mohammedans, but their history is that of a more or less fierce clash of Moslem religion and ancient African beliefs.

The chief difficulty here was the impossibility of self-defense on the part of various centers of culture and rising nations, and the overwhelming force that entered from time to time both from Europe and Asia. The proximity of these rising and falling empires and centers of culture to the cheap labor of the south led increasingly to the slave trade, which became a cause of demoralization and weakness, especially when encouraged and carried on by alien merchants. On the other hand the pressure of Sudanese kingdoms upon the ancient peoples of the West Coast not only weakened this indigenous African culture, cut it off from Europe, but left it a prey to the Christian slave trade. Thus the black civilization of the Sudan in a sense fell before the onslaught of two of the world’s great religions.