CHAPTER X

The Black United States

There were half a million slaves in the confines of the United States when the Declaration of Independence declared “that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The land that thus magnil-oquently heralded its advent into the family of nations had supported the institution of human slavery for one hundred and fifty-seven years and was destined to cling to it desperately eighty-seven years longer. The greatest experiment in Negro slavery as the base of a modern industrial system was made on the mainland of North America and in the confines of the present United States.

There were in the United States and its dependencies, in 1930, 11,891, 143 persons of acknowledged Negro descent, not including the considerable infiltration of Negro blood which is not acknowledged and often not known. Today the number of persons called Negroes is probably about thirteen millions. These persons are almost entirely descendants of African slaves, brought to America from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

The importation of Negroes to the mainland of North America was small until the British obtained the coveted privilege of the Asiento in 1713. After the Asiento treaty the Negro population in the confines of the United States increased in the eighteenth century from about 50,000 in 1710 to 220,000 in 1750 and 462,000 in 1770. When the colonies became independent, the foreign slave trade was soon made illegal; but illicit trade, annexation of territory and natural increase enlarged the Negro population from a little over a million at the beginning of the nine-teenth century to four and a half millions at the outbreak of the Civil War and to about ten and a quarter millions in 1914.

The present so-called Negro population of the United States is:

The census figures as to mulattoes1 have been from time to time officially acknowledged to be understatements. This blending of the races has led to interesting human types, but there has been little scientific study of the matter. In general the Negro population in the United States is brown in color, darkening to almost black and shading off in the other direction to yellow and white, and in some cases indistinguishable from the white population.

It has been estimated on admittedly partial data that less than twenty-five per cent of American Negroes are of unmixed African descent, the balance having in varying degrees Indian and white blood.2

The slaves, landing from 1619 onward, were usually transported from the West Indian marts, after acclimatization and training in systematic plantation work. They were received by the colonies at first as laborers, on the same plane as other laborers. For a long time there was in law no distinction between the indented white servant from England and the black servant from Africa, except in the term of their service. Even here the distinction was not always observed, some of the whites being kept beyond term of their service and Negroes now and then securing their freedom.

The opposition to slavery had from the first been largely stilled when it was stated that this was a method of converting the heathen to Christianity. The corollary was that when a slave was converted he became free. Up to 1660 or thereabouts it seemed accepted in most colonies and in the English West Indies, that baptism into a Christian Church would legally free a Negro slave. Masters, therefore, were reluctant in the seventeenth century to have their slaves receive Christian instruction. Maryland declared in 1663 that Negro slaves should serve durante vita, but it was not until 1667 that Virginia finally plucked up courage to attack the issue squarely and declared by law: “Baptism doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom, in order that diverse masters freed from this doubt may more carefully endeavor the propagation of Christianity.”

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was a considerable forced slave trade of whites from Europe under the guise of indentured servants. It met, however, not only the monopoly of feudal labor, but the new demand for labor purchase in the expanding industries of Europe. And, on the other hand, these very industries were encouraged and enlarged by the raw material raised in America by slave labor. The profits of the slave trade and of the plantations, together with the ease of obtaining black slaves through the systematic organization of the trade, increased the importation of black slave labor, while white free labor gradually replaced indentured workers.

The African family and clan life were disrupted in this transplantation; the communal life and free use of land were impossible; the power of the chief was transferred to the master, bereft of the usual blood ties and ancient reverence. The African language survived only in occasional words and phrases. African religion, both fetish and Islam, was transformed. Fetish survived in certain rites and even here and there in blood sacrifice, carried out secretly and at night; but more often in open celebration which gradually became transmuted into Catholic and Protestant Christian rites. The slave preacher replaced to some extent the African medicine man and gradually, after a century or more, the Negro Church arose as the center and almost the only social expression of Negro life in America. Nevertheless, there can still be traced not only in words and phrases but in customs, literature and art, and especially in music and dance, something of the African heritage of the black folk in America. Further study will undoubtedly make this survival and connection clearer.

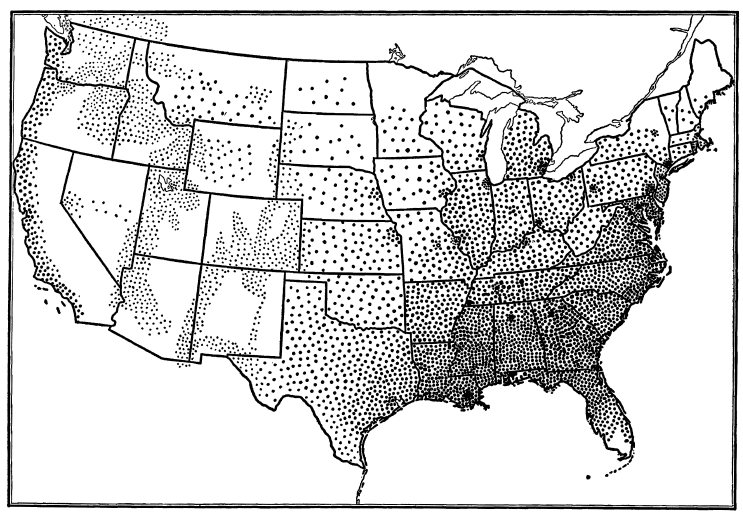

DISTRIBUTION OF THE NEGRO POPULATION IN THE UNITED STATES, 1930

The war of the American colonies against England in 1776 was an effort to escape the colonial status, in which the profits of agriculture and industry went to the mother country. In this struggle for industrial freedom and independence of England, the Negroes took part in considerable numbers, while others helped the Tories, tempted by offers of freedom. It was natural that at the conclusion of the war and at a time when the profits of the slave system were low, the small number of slaves in the northern colonies should be emancipated, partly in gratitude for their help during the war, and partly because the extinction of slavery in the new nation seemed inevitable.

The series of laws emancipating slaves in the North began in Vermont in 1779, followed by judicial decision in Massachusetts in 1780, and gradual emancipation in Pennsylvania beginning the same year; emancipation was accomplished in New Hampshire in 1783, and in Connecticut and Rhode Island in 1784. The momentous exclusion of slavery in the Northwest Territory took place in 1787, and, helped by Haiti, gradual emancipation began in New York and New Jersey in 1799 and 1804.

There early began to be some internal development and growth of self-consciousness among the Negroes: for instance, in New England towns during colonial times, Negro “governors” were elected. This was partly the African chieftainship transplanted, in an endeavor to put the regulation of the slaves partly into their own hands. Free Negroes voted in those days: for instance, in North Carolina until 1835, the constitution extended the franchise to every freeman, and when Negroes were disfranchised in 1835, several hundred colored men were entitled to vote. In fact, as Albert Bushnell Hart says, “In the colonies, freed Negroes, like freed indentured white servants, acquired property, founded families, and came into the political community, if they had the energy, thrift, and fortune to get the necessary property.”

In order to forward this movement, the Constitution permitted and subsequent legislation spurred by the Haitian revolt confirmed the abolition of the foreign slave trade. This meant not simply putting a stop to the further importation of slaves but also, and closely bound up with this, the firm conviction of all Americans that without an active slave trade the slave system would disappear. The Act of 1808, therefore, was conceived as a first and decisive step toward the overthrow of the old slave system and represented a triumph of abolitionism both North and South. Even then, however, there was some opposition to this legislation and open violation of it for many years because of the loss of slaves during the war and the consequent curtailment of the labor force on Southern plantations.

Two things ensued: Slavery changed in the United States from a slave-consuming to a slave-conserving system, and the Negroes, being more carefully treated, increased rapidly in number from a million to a million and three-quarters between 1800 and 1820. It was evident that the American Negro unassisted by the slave trade would not die out, and for that reason there arose the movement begun by the American Colonization Society in 1816 which resulted in the establishment of Liberia.

The forces back of colonization were fatally divided. Some wished to repatriate American Negroes in Africa and others wished to get rid of free Negroes so as to buttress the slave system. Simultaneously with this, came an increase of the cotton crop from 8,000 bales in 1790 to 650,000 bales in 1820. This phenomenal increase of a comparatively new crop was accompanied by the westward movement of the slave-cultivated area and by the birth of the Cotton Kingdom in the vivid minds of men, and the death of the colonization idea.

A new slavery began to appear, whose aim was production rather than consumption as represented by house service. It led to slave conspiracy and revolt dangerous in portent if not in actual fact. Several small insurrections are alluded to in South Carolina early in the eighteenth century, and one by Cato at Stono in 1739 caused widespread alarm. The Negro plot in New York in 1712 put the city into hysterics. There was no further plotting on any scale until the Haitian revolt, which shook the whole slave edifice to its foundation and terrified the New World. There were laws and migrations and a new series of plots. Gabriel in Virginia, in 1800, made an abortive attempt. In 1822 a free Negro, Denmark Vesey, in South Carolina, failed in a well-laid plot, and ten years after that, in 1831, Nat Turner led his insurrection in Virginia and killed fifty-one persons. The result of this insurrection was to crystallize tendencies toward harshness, which the economic revolution was making advisable.

A wave of legislation passed over the South, strengthening and enforcing the laws prohibiting the slaves from learning to read and write, forbidding Negroes to preach, and interfering with their religious meetings. Thus between 1830 and 1850 the philosophy of the South changed: it strongly repressed the slaves by a more careful patrol system; and it began to rationalize slavery with theories of race inferiority. In reaction from this there came the “Underground Railway” which systematized the regular and increasing running away of slaves toward the North, thus adding fuel and giving practical examples to the rising abolition movement.

The most effective revolt of the Negro against slavery was not fighting, but running away, usually to the North, which had been recently freed of slavery. From the beginning of the nineteenth century slaves began to escape in considerable numbers. Four geographical paths were chiefly followed: one, leading southward, was the line of swamps along the coast from Norfolk, Virginia, to the northern borders of Florida. This gave rise to the Negro element among the Indians in Florida and led to the two Seminole wars of 1817 and 1835. These wars were really slave raids to make the Indians give up the Negro and half-breed slaves domiciled among them. The wars cost the United States ten million dollars and two thousand lives. The great Appalachian range, with its abutting mountains, was the safest path northward, and this John Brown plotted to develop. Through Tennessee and Kentucky and the heart of the Cumberland Mountains, using the limestone caverns, was the third route, and the valley of the Mississippi was the western tunnel.

These runaways and the freedmen of the North soon began to form a group of people who sought to consider the problem of slavery and the destiny of the Negro in America. Negroes passed through many psychological changes of attitude in the years from 1700 to 1850. At first, in the early part of the eighteenth century, there was but one thought: revolt and revenge, with possible return to Africa. The developments of the latter half of the century brought an attitude of hope and adjustment and emphasized the differences between the slave and the free Negro. The African background was forgotten and resented. The first part of the nineteenth century brought two movements: among the free Negroes, an effort at self-development and protection through organization; and among slaves and recent fugitives, a distinct reversion to the older idea of revolt and migration.

On the other hand, the cotton crop leaped from 650,000 bales in 1820 to 2,500,000 bales in 1850 and was destined to reach the phenomenal height of four million bales in 1860. This new and tremendous economic foundation for a new Negro slavery increased the economic rivalry between the cotton-raising South and the increasingly industrialized North.

There seemed to the South two ways of escape from the domination which northern industry exercised over them by its larger capital, close organization and concentrated aims: one was to encourage industry in the South. Already there was a considerable number of slave artisans and some faint beginnings of a factory system. But if this was to be increased, slaves must be trained and educated or white artisans imported. Either alternative was dangerous for the slave system. The South feared free Negroes, and free Negroes were showing increasing group consciousness. They began to develop writers who expressed their reaction against slavery. They organized beneficial and insurance societies. They set up independent churches and fought in the War of 1812. In cities like Cincinnati and Philadelphia they came into sharp physical conflict with the white workers and as a result began to consider the possibilities of emigration from the United States. After a series of conventions, large numbers went to Canada where they were offered asylum, and later agents were sent to Central America, Haiti and Africa. Leaders arose like Frederick Douglass, who made his first speech in 1841, and a number of educated Negroes and others of ability went to Liberia and West Africa.

The second path which the white South considered for the development of an economy based on slavery was to build up an agricultural monopoly in the South and in slave territory which might eventually be annexed, and then make terms with industry both in the northern United States and in the world. This latter plan, however, called for accumulating capital in a spending and luxury-loving group, and for discipline and practical self-control to which the South had never been used. Nevertheless, the increasing cotton crop, and an almost unlimited world demand for it, seemed to insure the prosperity of the South, unless the slave system was interfered with; and the interference which the South would not and, in defense of its system, could not brook, was limitation of its political power by which it had hitherto maintained ascendancy in the nation. This political power was increased by counting three-fifths of the slave population. Slavery was forced north of Mason and Dixon s line in 1820; a new slave empire with thousands of slaves was annexed in 1850, and a fugitive slave law was passed which decreased fugitives even if it endangered the liberty of every free Negro and nullified the Common Law; finally determined attempts were made to force slavery into the Northwest in competition with free white labor, and less concerted but powerful movements arose to annex Cuba and other slave territory to the south and to reopen the African slave trade.

It looked like a triumphant march for the slave barons, but each step cost more than the last. Missouri gave rise to the early abolitionist movement. Mexico and the fugitive slave law affronted the democratic ideal in the North, and Kansas developed a counter-attack from the free labor system, not simply of the North, but of the civilized world. The result was war; a war not to abolish but to limit slavery. It was fought to protect free white laborers against the competition of slaves, and it was thought possible to do this by segregating slavery.

At this critical point the South proposed to establish a separate and independent state where the slave system would be absolutely protected politically and from which economically fortified retreat it could make terms with the industrial world. The North, on the other hand, was determined not to surrender a part of its territory which was not only a market for its manufactures and agricultural products but the source of raw materials—tobacco, sugar, and cotton.

In the revolution which ensued, the possible reaction of the slaves was ignored by all except the small party of abolitionists, with its contingent of free Negroes. In the end, however, this great mass of four million slaves settled the physical conflict, even though the mass of them remained on the plantations. They were from the first a source of great anxiety, and a considerable percentage of them at every opportunity ran away to the area occupied by Northern armies and became servants and laborers; eventually, to the number of 200,000, they became actual soldiers bearing arms.

The first thing that vexed the Northern armies on Southern soil during the war was the question of the disposition of these fugitive slaves, who began to arrive in increasing numbers. Butler confiscated them, Frémont freed them, and Halleck caught and returned them; but their numbers swelled to such large proportions that the mere economic problem of their presence overshadowed everything else, especially after the Emancipation Proclamation. Their flight from the plantation was not merely bewildered swarming; it was the growth of an increasingly purposeful general strike against slavery, after the well-known pattern of the Underground Railway. Lincoln welcomed and encouraged it, once he realized that even the idle presence of the Negroes was so much strength withdrawn from the Confederacy.

It gradually became clear to the North that here they had tapped a positive source of strength to their cause, which would balance the indisposition of large numbers of white Northerners, especially laborers and foreign immigrants, to enter the army; and also the South saw just as quickly that here was a point of fatal weakness which they had unconsciously feared. The moment that any qconsiderable number, not to mention the majority, of their four million slaves stopped work, much less took up arms, the cause of the South was lost.

The Emancipation Proclamation was forced not simply by the necessity of paralyzing agriculture in the South, but also by the necessity of employing Negro soldiers. During the first two years of the war no one wanted Negro soldiers. It was declared to be a “white man’s war.” General Hunter tried to raise a regiment in South Carolina, but the War Department disavowed the act. In Louisiana the Negroes were anxious to enlist, but were held off. But the war did not go as swiftly as the North had hoped, and on the twenty-sixth of January, 1863, the Secretary of War authorized the Governor of Massachusetts to raise two regiments of Negro troops. Frederick Douglass and others began the work of enlistment with enthusiasm, and in the end one hundred and eighty-seven thousand Negroes enlisted in the Northern armies, of whom seventy thousand were killed and wounded.

The conduct of these troops was exemplary. They were indispensable in camp duties and brave on the field, where they fought in two hundred and thirteen engagements. General Banks wrote, “Their conduct was heroic. No troops could be more determined or more daring.” Abraham Lincoln said, “The slightest knowledge of arithmetic will prove to any man that the rebel armies cannot be destroyed with Democratic strategy. It would sacrifice all the white men of the North to do it. There are now in the service of the United States near two hundred thousand ablebodied colored men, most of them under arms, defending and acquiring Union territory.… Abandon all the posts now garrisoned by black men; take two hundred thousand men from our side and put them in the battlefield or cornfield against us, and we would be compelled to abandon the war in three weeks.”

Emancipation thus came as a war measure to break the power of the Confederacy, preserve the Union, and gain the sympathy of the civilized world. It was this fact even more than the exhaustion of Southern resources and the success of Northern armies, which induced the South to surrender long before they had reached the theoretical limits of their resources. The emancipation of the slaves, promised during the war both as a moral sop to abolition sentiment and a needed addition to Northern resources, became a fact after Lee’s surrender. And then for the first time the nation had to sit down and consider a situation which it had never before envisaged realistically.

The initial settlement of the problem, proposed by the South, and at first not strongly opposed in the North, was to substitute serfdom for slavery; and a series of Negro codes to this end were passed by the Southern states. These were so unnecessarily drastic that they increased the sympathy with Negroes in the North, already well-disposed because of the military service of black soldiers.

To protect Negroes therefore, a Freedmen’s Bureau was proposed

Such an institution was bitterly opposed in the South as interfering with labor control, and given but half-hearted support in the North because it was too costly and a bad precedent in labor relations. The temporary makeshift which was actually enacted had neither time, sufficient funds nor proper organization for wide success.

Even under such conditions, the Freedmen’s Bureau in its short hectic life accomplished a great task. Carl Schurz, in 1865, felt warranted in saying that “not half of the labor that has been done in the South this year, or will be done there next year, would have been or would be done but for the exertions of the Freedmen’s Bureau.… No other agency except one placed there by the national government could have wielded that moral power whose interposition was so necessary to prevent Southern society from falling at once into the chaos of a general collision between its different elements.” Notwithstanding this, the Bureau was made temporary, was regarded as a makeshift, and soon abandoned.

Philanthropy poured out of the North to help the freedmen and establish schools; but the mass of Northerners were chiefly interested in the restoration of production and commerce and willing to leave the Negro to the control of the South, if this could be accomplished peacefully and profitably. The South was not satisfied with this and demanded increased political power, larger in proportion to its population than it had had before secession. This arose from the fact that each American Negro now counted for representation in Congress as one citizen instead of as three-fifths of a person, in accordance with the celebrated three-fifths compromise of the Constitution. Even with their normal political power, the returning South was a threat to Northern bond-holders, to the new national bank system, to the high tariff of manufacturers and to various other privileges and concessions which Northern industry had reaped during the war.

Northern industry gradually gained the support of an increasing feeling among the former abolitionists and ordinary American citizens, that the nation was rather shamelessly deserting its Negro allies; but the South, led blindly and stubbornly by Andrew Johnson, repudiated the Fourteenth Amendment and the establishment of a real Freedmen’s Bureau. As a result the North placed its reliance upon what was at once a settled American political doctrine and a new political expedient: the political doctrine of democratic control exercised by newly emancipated black slaves, which was in reality now a political expedient, by which the South with this threat of black labor dictatorship over it, would consent to the industrial policies which the dominant North wanted.

An experiment in democracy followed which instead of being a complete failure as most Americans no doubt thought it would be, was so successful that a new revolutionary bargain was needed to overthrow it. In 1867, a Dictatorship of the Proletariat was established in a large part of the South, with black and white workers in the majority. It was not a dictatorship conscious of any plan for continuing labor control of government. On the contrary, it was vitiated by the old American doctrine which assumed that any thrifty worker could become a capitalist. And yet this temporary dictatorship envisaged a chance for the poor freedman and the poor white to control enough wealth and capital to overturn the power of the former planters and slave barons. As steps toward this, they introduced democratic control in states where it had not been the rule; they began a new social legislation which gave government aid to the poor; they essayed protection from crime and furnished state capital to enterprises like railways. And above all, led especially by the blacks, they established a public elementary school system.

The chief charges against these labor and Negro governments are extravagance, theft, and incompetency of officials. There is no serious charge that these governments threatened civilization or the foundations of social order. The charge is that they threatened property and that they were inefficient. These charges are undoubtedly in part true; but they are often exaggerated. The South had been impoverished and saddled with new social burdens. In other words, states with smaller economic resources were asked not only to do a work of restoration, but a larger permanent social work. The property-holders were aghast. They not only demurred, but, predicting ruin and revolution, they appealed to “race” pride, secret societies, intimidation, force and murder. They refused to believe that these novices in government and their friends were aught but scamps and fools. Under the resulting circumstances directly after the war, the wisest statesman would have been compelled to resort to increased taxation and would have, in turn, been execrated by property-holders as extravagant, dishonest, and incompetent.

Much of the legislation which resulted in fraud was basically sound. Take, for instance, the land frauds of South Carolina. The Federal Government refused to furnish land. A wise Negro leader said, “One of the greatest slavery bulwarks was the infernal plantation system, one man owning his thousand, another his twenty, another fifty thousand acres of land. This is the only way by which we will break up that system, and I maintain that our freedom will be of no effect if we allow it to continue. What is the main cause of the prosperity of the North? It is because every man has his own farm and is free and independent. Let the lands of the South be similarly divided.” From such arguments the Negroes were induced to aid a scheme to buy land and distribute it. Yet a large part of eight hundred thousand dollars appropriated found its way to the white land-holders’ pockets through artificially inflated prices.

The most inexcusable cheating of the Negroes took place through the failure of the Freedmen s Bank. This bank was incorporated by Congress in 1865 and had in its list of incorporators some of the greatest names in America, including Peter Cooper, William Cullen Bryant, and John Jay. The bank did excellent work in thrift and saving for a decade and then through neglect and dishonesty was allowed to fail in 1874, owing the freedmen their first savings of over three millions of dollars. They have never been reimbursed.

Many Negroes and whites were venal, but more were ignorant and deceived. The question is: Did they show any signs of a disposition to lean to better things? The theory of democratic government is not that the will of the people is always right, but rather that normal human beings of average intelligence will, if given a chance, learn the right and best course by bitter experience. This is precisely what the Negro voters showed indubitable signs of doing. First, they strove for schools to abolish ignorance, and, second, a large and growing number of them revolted against the extravagance and stealing that marred the beginning of Reconstruction, and joined with the best elements to institute reform. The greatest stigma on the white South is not that it resented theft and incompetence, but that, when it saw the reform movements growing and even in some cases triumphing, and a larger and larger number of black voters learning to vote for honesty and ability, it still preferred a Reign of Terror to a campaign of education, and disfranchised men for being black and not for being dishonest.

In the midst of all these difficulties, the Negro governments in the South accomplished much of positive good. We may recognize three things which Negro rule gave to the South: (1) democratic government, (2) free public schools, (3) new social legislation.

There is no doubt that the thirst of the black man for knowledge, a thirst which has been too persistent and durable to be mere curiosity or whim, gave birth to the public school system of the South. It was the question upon which black voters and legislators insisted more than anything else, and while it is possible to find some vestiges of free schools in some of the Southern States before the war, yet a universal, well-established system dates from the day that the black man got political power.

Finally, in legislation covering property, the wider functions of the state, the punishment of crime and the like, it is sufficient to say that the laws on these matters established by Reconstruction legislatures were not only different from and even revolutionary to the laws in the older South, but they were so wise and so well-suited to the needs of the new South that, in spite of a retrogressive movement following the overthrow of the Negro governments, the mass of this legislation, with elaboration and development, still stands on the statute books of the South.

In the process of accomplishing this revolutionary change in Southern economy there was waste and theft due in part to ignorance and in part to the deliberate connivance of the best elements in the community, who were determined that Negro suffrage and labor control should cease. The old planter class was decimated by the war and hard experiences after the war, and their place taken by new capitalists, some trained after the Northern industrial pattern and all eager to follow it. This new leadership of the South was eager to strike a bargain with the industrial North and they did so in 1876.

The bargain consisted in allowing the Southern whites to disfranchise the Negroes by any means which they wished to employ, including force and fraud, but which somehow was to be reduced to semblance of legality in time. And then that the South hereafter would stand with the North in its main industrial policies and all the more certainly so, because Northern capital would develop an industrial oligarchy in the old South.

Forcible overthrow of democratic government in the South followed from 1872 to 1876. Negroes were kept from voting by force and intimidation, while whites were induced to vote as employers wished by emphasized race hate and fear. The disfranchisement of 1876 and later was followed by the widespread rise of “crime” peonage. Stringent laws on vagrancy, guardianship, and labor contracts were enacted and large discretion given judge and jury in cases of petty crime. As a result Negroes were systematically arrested on the slightest pretext and the labor of convicts leased to private parties.

In more normal economic lines, the employers began with the labor contract system. Before the war they owned labor, land and subsistence. After the war they still held the land and subsistence. The laborer was hired and the subsistence “advanced” to him while the crop was growing. The fall of the Freedmen’s Bureau hindered the transmutation of this system into a modern wage system, and allowed the laborers to be cheated by high interest charges on the subsistence advanced and in book accounts.

The black laborers became deeply dissatisfied under this system and began to migrate from the country to the cities, where there was a competitive demand for labor and money wages. The employing farmers complained bitterly of the scarcity of labor and of Negro “laziness,” and secured the enactment of harsher vagrancy and labor contract laws, and statutes against the “enticement” of laborers. So severe were these laws that it was often impossible for a laborer to stop work without committing a felony.

Nevertheless competition compelled the landholders to offer more inducements to the farm hand. The result was the rise of the black share tenant; the laborer, securing better wages, saved a little capital and began to hire land in parcels of forty to eighty acres, furnishing his own tools and seed and practically raising his own subsistence. In this way the whole face of the labor contract in the South was, in the decade 1880–90, in process of change from a nominal wage contract to a system of tenantry. The great plantations were apparently broken up into forty and eighty acre farms with black farmers. To many it seemed that emancipation was accomplished, and the black folk were especially filled with joy and hope.

It soon was evident, however, that the change was only partial. The landlord still held the land in large parcels. He rented this in small farms to tenants, but retained indirect control. In theory the laborer was furnishing capital, but in the majority of cases he was borrowing at least a part of this capital from some merchant at usurious interest.

Nevertheless, Negroes had begun the accumulation of land and property and had eagerly accepted the democratic ideals of popular suffrage and the eventual accomplishment of social and economic salvation by means of the vote. In the two decades from 1880 to 1900 they tried desperately to put this program into accomplishment by efforts to regain their lost political power; but these were the years of tremendous expansion of industry and wealth in the United States and the world over; government was dominated by business and the possibility of any real political influence on the part of a poor and socially excluded minority was extremely small.

The illegal disfranchisement of the Negro, against which he was protesting in season and out, now began to be buttressed by law. In 1890 Mississippi disfranchised Negroes by a literacy test, securing the acquiescence of the ignorant whites by requiring on the part of the prospective voter either the ability to read or “understand” a part of the Constitution read to him by sympathetic officials. South Carolina followed in 1895 by an illiteracy or property test and the Mississippi “understanding” clauses. In 1898 Louisiana enacted an illiteracy and property test and added to that the celebrated “Grandfather Clause” which allowed persons to vote whose father or grandfather had had the right to vote before Negroes were enfranchised. Variations and elaborations of this kind of disfranchisement followed in Alabama in 1901, Virginia in 1902, in Georgia in 1909. Not only were these laws clearly unfair if not unconstitutional, but their administration was openly and designedly discriminatory. Yet in the cases rushed before the courts, they were invariably upheld; indeed it was not until 1915 that even the “Grandfather Clause” was declared unconstitutional.

To all this was added a series of labor laws making the exploitation of Negro labor more secure. All this legislation had to be accomplished in the face of the labor movement throughout the world, and particularly in the South, where it was beginning to enter among the white workers. This was accomplished easily, however, by an appeal to race prejudice. No method of inflaming the darkest passions of men was unused. Racial sex jealousy was especially emphasized. The lynching mob was given its glut of blood and egged on by purposely exaggerated and often wholly invented tales of crime on the part of perhaps the most peaceful and sweet-tempered people the world has known. Labor laws were so arranged that imprisonment for debt was possible and leaving an employer could be made a penitentiary offense. Negro schools were cut off with small appropriations or wholly neglected, and a determined effort was made with wide success to see that no Negro had any voice either in the making or the administration of local, state, or national law.

The acquiescence of the white labor vote of the South was further insured by throwing white and black laborers, so far as possible, into competing economic groups and making each feel that the one was the cause of the other’s troubles. The neutrality of the white people of the North was secured through their fear for the safety of large investments in the South, and through the fatalistic attitude common both in America and Europe toward the possibility of real advance on the part of the darker peoples.

It was natural that a leader should arise at this time who should point out the necessity of economic adjustment before political defense was possible. Booker T. Washington in his celebrated speech in Atlanta in 1896 enunciated this principle and united under his leadership Southern whites who wanted nothing so much as an end to political pretentions on the part of Negroes; Northern whites who wanted to encourage the development of a dependable labor force in the South not dominated by the labor class consciousness of the North; and by Negroes who were willing to give up their right to vote and hold office if they but had a chance to earn a living.

What Mr. Washington did not see or understand was the connection of his movement with the labor movement of the world. His idea was to develop skilled labor under the benevolent leadership of white capital; and out of wages to save capital so as to develop a Negro bourgeoisie who would hire black labor and co-operate with white capital. He did not know the difficulty, indeed the practical impossibility, of this program, when capital was willing to exploit race prejudice and the rivalry of race groups in industry, and at a time when the possibility of accumulating capital on the part of laborers and in competition with the great monopolies of capital in the industrial world was rapidly coming to an end. Even more than that, he did not foresee, perhaps could not have foreseen, the disappearance of special technical skills before mass production and the impossibility of establishing a permanent system of education based on the handing on of skills which might easily become obsolete in a generation or even in a day.

The political revolt of white labor against prevalent conditions began about 1880 and American farmers joined the movement by 1890. Populism arose both in the West and in the South, but Negroes paid little attention to it. They were bound up in the Washington idea that their salvation lay in close alliance with capital. The result was that there was some alliance between black and white labor in the South, as for instance when Negro Republicans and white Populists elected a congressman in North Carolina in 1896; in Georgia on the contrary, Tom Watson, exasperated because the Populists did not get a larger Negro following, tried the experiment of joining the forces for Negro disfranchisement and anti-Semitism, and thus cut the labor foundation from under his own feet.

This failure on the one hand of Negroes to make common cause with white labor and the failure of white labor on the other hand to invite or desire their co-operation, together with the bitter agitation for disfranchisement, increased mob violence and lynching. The lynchings in one year, 1892, numbered two hundred thirty-five. In the period between 1882 and 1927 nearly five thousand persons were lynched in the United States, and three thousand five hundred of these were Negroes. Race hatred reached an apogee, and with it came the series of laws in the South and some Northern states which established persons of Negro descent as a caste with curtailed civil rights in matters of marriage, travel, residence, and social intercourse.

The twentieth century saw a determined effort on the part of Negroes to stem this tide. They had made efforts at general organization within racial lines since the first convention in 1830; and just before and during the Civil War they had held a number of very effective general congresses. In the nineties they started the Afro-American Council as a national organization, which held annual meetings and served to consolidate public opinion. But the real effective effort came in 1905 with the Niagara Movement which clarified and laid down a new clear bill of rights. In 1910 the leaders of the Niagara Movement were joined by a large number of white liberals and the resulting organization was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The Association proved, between 1910 and the World War, one of the most effective organizations of the liberal spirit and the fight for social progress which the Negro race in America has known. It won case after case before the Supreme Court, establishing the validity of the Fifteenth Amendment, the unconstitutionality of the “Grandfather Clause” and the illegality of residential segregation. Above all, it began a determined nation-wide and interracial fight against lynching which eventually reduced this relic of barbarism from two hundred thirty-five victims a year to eighteen.

The World War radically altered this whole situation. First of all came the economic results. Immigration since the Civil War had poured into the North such a mass of laborers that industry had a reservoir of labor at low prices which they could discharge and rehire at will. This abundance of labor had kept the Negro largely out of industry in the North, because of exacerbated race prejudice and fear of wage under-bidding, which on the other hand largely repelled foreign immigration to the South; and in the whole land excluded Negroes, by competition and lack of opportunity, from learning skilled operations.

The War stopped this flow of immigrants as early as 1914 and with equal suddenness the Negro began to pour into the North, until by 1920 black workers and their families to a total of two million had left the South. This caused difficulties of competition for jobs with whites, which resulted in riots in East St. Louis, Chicago, Pennsylvania, Washington and elsewhere. Despite this the Negro found work and the best paid work that he had been able to do since emancipation.

The result was a great increase in his economic power, and also his political influence as a voter, especially in Northern cities and as part of a new labor movement with which he began to make tentative alliance. When the United States was drawn into the war, his power was revealed. The government had to pay him special attention. German propaganda was feared. A conference of Negro editors was held in Washington; a Negro was made adviser to the Secretary of War; and when the War Department determined not to appoint Negro officers, a nation-wide Negro agitation compelled the opening of a special camp for their training. Eventually seven hundred Negro officers were commissioned. Of all the white nations that took part in the World War, the United States was the only nation that recognized its colored constituents to any such extent. England did not have a single officer of acknowledged Negro blood; France had many, but no such number as America.

After the war and with the depression, the Negro’s position again became critical. Mass production gave him entrance into industry formerly largely monopolized by skilled white workers, but the general depression threw the Negro first into the ranks of the unemployed. He was saved from something like economic annihilation by his increased political power, based on the black population in cities like New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Pittsburgh and Chicago. After a lapse of thirty years, one Negro congressman appeared in Washington and Negroes became members of state legislatures in a dozen different states and were represented on city councils. While they lost a good many of the more spectacular political jobs that were formerly set aside for them, they gained representation for merit and training in a number of less conspicuous but important positions under the New Deal.

But above all they had to examine again the balance of importance between political and economic power. It was pointed out that the casting of a ballot must not be simply for the election of officials or to settle at infrequent times, broad contrasting matters of policy; but rather that real democracy can be attained only when the laborer can express his wishes in industry; when he has a voice in the production and distribution of wealth. And while the broad accomplishment of this great advance in human progress is not in the hands of the Negro voter today, he has the opportunity of starting toward it through the organization of his power as a consumer and by utilization of the cultural bands of his racial grouping to secure industrial emancipation.

Meantime the American Negro forms an important group. It has a population larger than Sweden, Norway and Denmark together and owned, before the depression, land equal to half the area of Ireland. He forms nine and seven-tenths per cent of the population of the land, with nine and one-third million of its population living in the South and two and one-half million in the North. Fifty-six per cent live in towns and cities of two thousand five hundred or more. The crude death rate in the registration area is 18.7 per 1,000 of population, but most Negroes live outside this area. The illiteracy of this population ten years of age and over is reported as 16.3 per cent, although probably in reality it is considerably larger than this. Two and one-half million Negro children are in school.

The Negroes are occupied as farmers, laborers and servants; 36 per cent being engaged in agriculture; 19 per cent in manufacture and mechanical industries, chiefly as laborers and porters; and 28 per cent in domestic and personal service. In addition to these there are 25,000 clergymen, 56,000 teachers, 4,000 physicians, 2,000 dentists, 1,200 lawyers, 6,000 trained nurses and 11,000 musicians. Beside these there are 34,000 barbers and hairdressers, 108,000 chauffeurs and truck drivers, 28,000 retail dealers, 6,000 mail-carriers, 11,000 masons, 21,000 mechanics, 15,000 painters.

At the Census of 1930, the number of Negro farm operators was 882,850, with 37,597,132 acres; the value of the land and buildings, $1,402,945,799. Their ownership was 20.5 per cent; the number of farms owned, 181,016, and the value of their owned land and buildings $334,451,396. Negro representation is weakest in the higher ranks of skilled labor, business and commerce. Nevertheless, Negroes are so integrated in American industry that they are for the present at least indispensable.

There are 42,500 Negro churches with five million members and property worth $200,000,000. In American poetry, prose literature, music and art, the Negro has gained notable recognition. In sports and physical prowess, representatives of this race have continually come to the fore.

It is astonishing how the African has integrated himself into American civilization. The first national holiday, the fifth of March, commemorated the death of Crispus Attucks. In the War of 1812, the Civil War, the Spanish War and the World War, Negro soldiers were prominent.

Paul Cuffee began agitation and a movement to Africa, and David Walker’s Appeal anticipated the abolition movement. That movement received indispensable aid from Douglass, Remond and Sojourner Truth. After the Civil War, Lynch of Mississippi, Cardozo and Eliott of South Carolina, and Dunn and Dubuclet of Louisiana were recognized as able political leaders.

In science, Banneker issued early American almanacs and assisted in surveying the city of Washington. Later Just made a record in biology; Turner in entomology and Fuller in psychiatry; Hinton is today a leading American authority on syphilis.

In religion, Richard Allen was a national leader; Payne and Turner prominent and forceful; and Pennington received his doctor of divinity from Heidelberg in 1843. Chavis and Booker Washington were leading educators; George Leile and Lott Carey led in American foreign missionary effort. As inventors Matseliger founded our pre-eminence in shoe manufacture, Rillieux in sugar and McCoy began the lubrication of running machinery.

But it is in art that the Negro stands pre-eminent: his folk song began its wide influence with the Fisk Jubilee Singers; and was followed by the compositions of the Lamberts, Rosamond Johnson, Dett, Burleigh and Handy. There are the great voices of the “Black Patti,” Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson. For years, before his recent death, Henry O. Tanner was the dean of the American painters. The stage has had no comedian to surpass Bert Williams and every year brings a new dramatic figure like Gilpin and Richard Harrison.

The Negro’s work in literature was begun by Phyllis Wheatley. She was not a great writer, but she led American literature in her day. In Louisiana in 1843–45, Negroes published an anthology of their poetry which represents a higher literary standard than anything contemporary in the United States. In the early twentieth century came Chesnutt and Dunbar, Braithwaite who revived appreciation for poetry in America; James Weldon Johnson and Benjamin Brawley. The record, by no means complete, is an astonishing proof of the capacity of the Negro race.