ONE

Shopping for Status

Shun the cheap and shoddy as you would a contagious disease and … sink your all in a few perfect clothes. Well-made shoes, well-cut clothes of classic, lasting style, good hats, however few in number – these form the foundation of our lady’s wardrobe.1

Vogue, 1931

Where people shop has always been a good indicator not just of their taste but of their social aspirations. Vogue’s advice from 1931 encapsulates the aims of the female middle-class shopper. Achieving them was another matter. First, there was the question of how to pay for these quality goods. Salaries and housekeeping rarely matched expectations. Secondly, people’s loyalties to their traditional style of shop were being challenged as new types of shops and stores started appearing across the country.

During the interwar period large-scale manufacturers and retailers gradually changed the face of the British high street forever. Lawrence Neal, head of Daniel Neal’s, famous until the 1960s for their range of ‘sensible’ children’s shoes, wrote a review of British retailing in 1933.2 He divided it into six categories: department stores; multiple shops, such as Burton’s or Freeman, Hardy & Willis; speciality shops such as Austin Reed’s; the Co-operative Movement; ‘fixed-price’ chain stores such as Woolworth’s, Marks & Spencer or British Home Stores; and finally, small independent shops. In addition he looked at ‘clothing clubs’ and mail order, but makes no mention of the ‘hire’ and second-hand markets even though they clearly existed. Nevertheless, he accurately assessed that there was a wide and growing variety of retailing outlets across the country to suit all tastes and classes.

Most of England’s department stores had been established in the early twentieth century. By the 1920s major cities had at least one department store while mid-sized towns had large specialist clothing stores. Department stores sold 10 per cent of all clothing and footwear in 1920, increasing to just over 15 per cent by 1939.3 Sales were buoyed by the development of mass production. In 1920 there were also nearly 6,000 branches of smaller multiple clothing retailers, such as Burton’s and Freeman, Hardy & Willis, which grew to nearly 10,000 by 1939.4 Their market share rose from 8.5 per cent in 1920 to just over 20 per cent in 1939. These figures, when combined with figures from the Co-operative Societies, which went from 5 per cent in 1920 to 7.5 per cent in 1939, show how shopping habits changed within twenty years.5 In 1920 75 per cent of clothing and footwear was bought from small independent retailers but by 1939 this figure had dropped to 50 per cent as larger chain stores increasingly dominated the market.6

From the turn of the twentieth century department stores had aimed at the middle-class market.7 During the 1920s and 1930s, for example, within the Debenhams network stores were graded ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’, being ‘high class’, ‘popular to medium class’ and ‘just popular’ respectively.8 This was reflected in the standard of goods they sold. Management advised ‘C’ class stores to be ‘second in fashion, whilst the first burnt their fingers’.9

Stores increasingly used inducements to entice customers through their doors. Publicity stunts included celebrity visits and roof-garden fashion shows such as those held at Selfridges throughout this period.10 Simpson’s had three aeroplanes on the top floor of its store in Piccadilly in 1936,11 while Kennards of Croydon, a ‘C’ group store aiming at the ‘just popular’ market, borrowed two elephants from a visiting circus in the 1930s to promote a ‘jumbo’ sales event.12

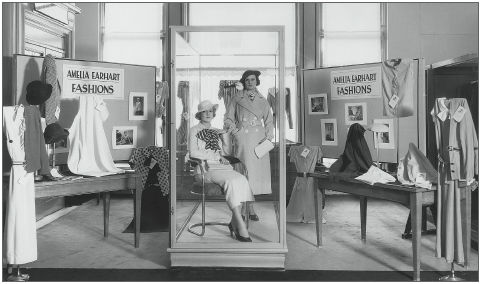

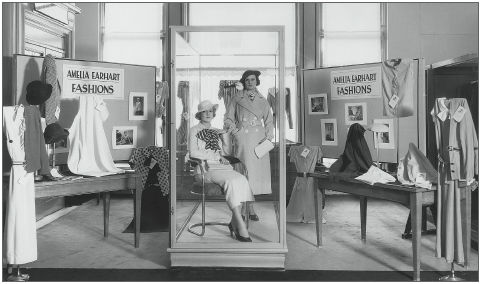

Large retailers also encouraged consumers to linger by installing hairdressing and beauty salons and coffee shops. City businessman’s daughter Eileen Whiteing remembers taking tea with her mother at Kennards of Croydon ‘all to the strains of light music from the inevitable trio or quartette [sic], often of ladies only, hidden behind a bank of palms and plants’.13 Selfridges was also among the first stores to use not only celebrity appearances but also marketing of particular lines of clothing to capture sales. In the 1930s they devoted a section of the women’s wear department to promoting a range of clothes inspired by the popular female flying ‘ace’, Amelia Earhart.14 Earhart was one of many sports stars in the interwar years who endorsed clothing lines.

Stores which wanted to attract a higher class of customer concentrated on offering good service. Harrods Man’s Shop, for example, aimed to give a standard of personal service similar to that of a smaller specialist quality shop such as Austin Reed.15 Most major department stores offered to send goods ‘on approval’. Ordering an item ‘on appro’ was a form of mail order and a way of offering customers extended credit since they did not need to pay for the goods until they had been received and accepted. Eileen Whiteing’s mother, wife of a City managing director, regularly ordered a selection of hats ‘on approval’ from Aldis & Hutchings in Croydon.16 Harrods chairman Sir Woodman Burbidge claimed in 1933 that the approval system worked because advertisements had improved so much that ‘a woman would know that the article she was ordering would suit her requirements’.17 Figures for items returned are not available to confirm or deny his claim but it was undoubtedly a popular marketing ploy aided by a cheap and reliable postal system.

Stores tried to attract new customers with celebrity promotions such as this display put on by Selfridges in Oxford Street of a range of clothes inspired by American female flying ace Amelia Earhart and featuring the top model of the time, ‘Gloria’. (From the Selfridges collection at the History of Advertising Trust Archive)

Department stores such as John Lewis and Harrods carefully fostered and maintained their middle-class status. In 1932 Harrods regularly sent out brochures to their account customers to encourage sales. The John Lewis Partnership followed suit with ‘Customers’ Gazettes’ and ‘Monthly Special Notices’. There was great concern that the newsletters should avoid ‘such vulgarities’ as the use of words such as ‘kiddies’.18 Similarly, the chairman of the John Lewis Partnership was horrified by the ‘nastily cheap’ reproductions of women’s clothing:

I am writing this in ignorance of the opinion of the Deputy Chairman. I am waiting with real interest to hear whether she considers that for our real public, that is to say the cultivated people, who are thrifty but not ‘impossibly’ hard up, the kind of cheap-and-nastiness, that we seem to me to be failing at present to avoid, is of serious importance … I am not suggesting for a moment that the opinion of any one lady, however typical a customer she should seem to us to be, should be accepted at all uncritically. I have a strong suspicion that Sir Algernon has been misled quite seriously by the extent to which he has relied upon the guidance of his own wife whom I should certainly consider to be typical of the public at which I have sought to aim the steering of his company.19

Unfortunately, the reply of the deputy chairman is not recorded but clearly ‘cheap-and-nastiness’ is something to be avoided.

Department stores catering for the lower middle classes were challenged by the newer concept of chain stores selling only own-label clothes.20 One such clothing chain, C&A, openly targeted the lower end of the market. Retailer Lawrence Neal, writing in 1933, felt its new style of selling was ‘particularly interesting … in that it illustrates the combination of mass-production methods with a multiple distributive organization’.21 When C&A opened its first major store in London in 1922, it was among the first to offer only its own-label clothing, ‘the Height of Fashion at the Lowest Cost’. They made a point of saying that they did not offer a mail-order service.22 This was presumably in an effort to keep down costs.

C&A’s second major British store was in Liverpool. Advertisements for the opening played on the London/Paris fashion connection promising ‘the wonderful shopping atmosphere associated with Paris and the West End of London’.23 In contrast, advertising for the London opening had stressed the economic value of their clothes without mentioning Paris. Subsequently, no distinction was made between advertisements for its various stores, which soon included Birmingham, Glasgow and Southampton.24 C&A, aiming at the lower middle classes, rarely suggested emulation as a motive for buying their clothes. Apart from the initial mention of Paris and ‘the height of fashion’, thriftiness became their leitmotif.25

The small shops could not compete with department and chain stores in terms of advertising expenditure. Even C&A, among the top ten retail advertisers of women’s clothes, was regularly surpassed by store giants like Barkers and Selfridges.26 Barkers dominated West London, offering in its namesake store ‘high-class lines’ while its junior partners, Pontings and Derry & Toms, carried their middle-class counterparts.27 Nevertheless, there is little doubt that Barkers had to move with the times and introduce facilities such as tearooms and toilets as inducements to female customers to lure them away from the West End.28

In contrast, a local store could provide the personal touch that many middle-class consumers liked.29 Residents would be aware of the status of both the large and the small shops in their area. Mrs B. noted as a teenager that in Croydon where she grew up there was a ‘very nice shop … called Grant’s, and a not at all nice [one] called Kennedy’s’. She envied her best friend Susan who ‘used to have very expensive clothes from Grant’s’.30 Similarly, Cape & Co., a department store in Oxford, with a working- and lower-middle-class clientele, found it hard to compete with Elliston & Cavell, the ‘grander and larger business’.31

The upper-middle-class man or women would try to buy clothes in the leisurely manner of someone who had time and money to spare. Families were loyal to stores that treated them with the appropriate deference.32 Ella Bland remembers women talking of ‘my milliner’, ‘my furrier’ and ‘our tailor’.33 Shopkeepers would open the door for regular customers and ‘shop-walkers’, senior store staff, would cater for the needs of favoured customers. The walker in Brighton drapers Chipperfield & Butler was ‘always flawlessly dressed in frock-coat and tails’, recollects Leonard Goldman who worked there as a junior salesman in the 1920s.34 In Croydon Eileen Whiteing recalls her and her mother being given chairs to sit on in local drapers Aldis & Hutchings ‘while we made a leisurely selection’.35

The ties of loyalty could be strong. When Mrs A. moved from Wantage in Berkshire to Croydon in south London she continued to buy clothes from her favourite local drapers, Arbery & Son.36 Mrs R., an MP’s daughter from Gloucestershire, remembers her mother getting her clothes from a shop in Cheltenham called ‘Madam Wright’: ‘Practically once a week I think she managed to go there. She was pretty extravagant about clothes. They weren’t terribly fashionable, but they weren’t frumpish either, not at all. They were just like the sort of clothes you would expect from a shop that called itself Madam Wright.’37

Most towns offered a selection of clothing retailers to suit different price ranges. Worthing had ‘a considerable number of shops specialising in clothing as well as private dressmakers catering for the wealthy clientele of west and north Worthing, and the affluent areas nearby’.38 Lewes in Sussex had five shops that sold menswear. Although they may have had to pay a little bit more than in larger towns, locals felt no need to leave the town to buy clothing.39

Most towns in southern England had a selection of small dress shops called ‘Madam’ shops in the trade.40 One such was Joan Laurie’s of Worthing and Brighton, owned by a Mrs Fletcher, confusingly known as Madam Barnett.41 Records of such shops are rare since they were usually owned by individuals and documentation was often destroyed when they closed. Although there were fewer shops of this type in the North, they did exist. Leonard Goldman’s aunt Esther ran such a shop in the Gorbals district of Glasgow. He describes his aunt as having been ‘somewhat flamboyant’, saying ‘she knew what suited her and within the limitations of her background, she had, if not exactly good taste, then at least a flair, which certainly drew attention to her even in a fashionable [southern] resort like Brighton’.42

Esther Goldman’s shop would have been similar to the one set up by Blackburn-born Dorothy Whipple’s heroine in High Wages.43 Having worked for little money for a draper’s in her unnamed northern town, the heroine Jane decided to open her own shop. Whipple’s description of the window display on its opening day captures its trim modesty and daintiness.

In the window … was an elegant white embroidered frock with a yellow necklace laid on it. Three equally elegant white embroidered blouses were disposed on the other side of the window; and just where it should be was a bowl of yellow globe flowers to point the colour of the necklace. Jane thought it discreet, fresh and delicious.44

‘Madam’ shops such as these tried to offer a personalised service, knowing each customer’s requirements intimately. Eric Newby’s experience as a wholesale representative for his family’s London-based firm shows that little had changed even in the 1950s.45 A Scottish shop owner with a business in the Borders told him, ‘it seems to us that you are not au fait with the requirements of our ladies. They do not want mass-produced garments … our ladies would not wear such a garment, Mr Newby!’46

In the late 1930s there were also around 30,000 retail drapers and gentlemen’s outfitters, selling socks, shirts, haberdashery and underwear to a clientele they would have known well.47 As a young sales assistant in a Brighton drapery store in the 1930s, Leonard Goldman learned quickly that there was more than taste in clothes to master.

Several of the staff were from a middle-class background and as, in those days, accent mattered, it wouldn’t do to be heard using an ‘inferior’ one. One had to keep up with the Jones’s. But perhaps this was even more true when it came to the customers. If they spoke that way you had to match them. If they didn’t, your assumed upper-class accent somehow gave you the edge.48

BALANCING BUYING AND BUDGETS

For women with a comfortable income shopping was often a treat. For those on a lower income it was sometimes a struggle but nevertheless pleasure could be taken in the planning of a purchase and the shopping trip itself.49 Mass-Observation surveyed their respondents on shopping habits in April 1939, asking them to describe the steps leading to the purchase of a main article of dress. By far the most popular activity was window-shopping. Two-thirds of the women looked in shop windows for ideas while just under half used magazines and advertisements for inspiration. Vogue was the fashion mentor of the time with women across the middle classes referring to it as a fashion guide and mentioning it more than any other magazine.50

Not surprisingly, young working women under thirty showed the greatest interest in shopping for clothes. Few respondents took sales assistants’ advice, preferring to discuss what they might buy with female friends instead.51 Mrs B., a housewife from Dorking in Surrey, bemoaned the problems of dealing with assistants working on commission, which was common practice in many smaller shops and stores until the 1970s, showing that ‘service’ can itself be a problem:

The biggest pitfall to be avoided is falling into the clutches of the Jewish type of saleswoman, who will over-persuade you with glib patter. Then you will find yourself with a garment which usually spends the rest of its life hanging in your wardrobe and which reproaches you each time you see it. I am very easily persuaded by people like this, so the only thing to do is to avoid all such shops (they are a very definite type) and only go to big shops or shops where you know the salesgirls are reliable.52

This unmistakably anti-Semitic tone was not uncommon in references to sales assistants.53 Shopping for ‘costumes’ to go up to Oxford for the first time, Jenifer Wayne recalls her mother, with ‘Anglo-Saxon determination’ delighting in visiting little ‘gown shops’ in Soho, each with ‘its full-blown Jewess beaming in the doorway between the small plate-glass windows’.54 Yet, as Leonard Goldman confirms, a young sales assistant like him could get into trouble if a customer ‘swapped’, meaning walking out without buying.55

Outside the big cities those on a lower income also used the media and shop windows for inspiration, as Mrs E., a housewife from Burnley, showed:

I always study fashion articles, advertisements, women’s magazines to keep my ideas up to date. I never discuss with friends, but I take note of what well-to-do people wear, and notice photographs of the Queen or Duchess of Kent as naturally the fashion houses who dress these people should know what is coming in. I take every chance of studying the displays in the best shops though I could not afford to patronize them. Fashion in this locality lags behind the fashion in a large city like Manchester so I like to see the shops there.56

Professional working women were not above window-shopping either. The memoirs of Marion Pike, both a student and later staff member of Royal Holloway College, reveal that staff members frequently browsed the London shops for an hour before late afternoon meetings, enabling them to ‘get one’s eye in for really earnest shopping, which was done in vacations’.57

The pitfall of mass production was that a wider class spectrum could now buy cheaper variations of smart clothes. Therefore women who wished to be fashionably turned out not only had to keep abreast of current trends but they also had to be aware of what, as one Mass-Observation respondent, Miss D., a female secretary in London, put it, was ‘going to be “run to death” and therefore … quickly disappear from the better shops’.58

Whether for work or for leisure, the selection of clothes for the middle-class woman’s wardrobe was governed by a longing for quality. As Mrs E.E. from Pwllheli notes, ‘We were all taught “one good thing was better than two cheap ones”.’59 A middle-class housewife from south London, who considered herself impoverished, admitted she felt superior to those who had the money to dress well but not, in her opinion, the taste. She did feel embarrassed when staying with her husband’s ‘people’ who were ‘very county’. There she would be attended by her aunt-in-law’s maid and felt that her wardrobe was ‘lacking’. ‘I spend less and have practically no clothes as compared with the other women around here,’ she noted, ‘but I do not think I look too badly dressed.’ Since she lists the places she shopped at as Debenhams, Harrods, and Reville & Bradley’s, all high-class stores and shops, she was obviously looking for quality rather than quantity, the mark of the aspiring middle-class woman.60

The necessity to buy quality was a burden for many middle-class women. From the early 1920s women’s magazines such as The Lady increasingly acknowledged that there was a financial pressure being felt by what were termed the ‘new poor’.61 At the same time Browns of Chester, ‘the Harrods of the North’, brought in a ‘new lower price level policy [knowing] the purchasing power of the great majority of people has been drastically curtailed’.62 Whether this was a perceived pressure or a real one is hard to judge since in real terms the pound in the pocket was steadily buying more for consumers during the 1920s and 1930s.63

Figures for middle-class expenditure in 1938–9 show that both men and particularly women in the lower income groups spent significantly more proportionately on clothing than those better off .64 It is not surprising either that the lower income groups’ repair bills were higher as well, a consequence of their efforts to economise and maintain standards. With new domestic consumer goods, particularly electrical items, becoming available, budgets had to be stretched that much further. In all middle-income households, from those earning more than £250 a year to those earning over £700 a year, 20 per cent more is spent on clothing than on household items including furniture and domestic equipment, confirming the importance of appearance to the middle-class family.65

A rare set of accounts left by a wealthy Yorkshire housewife in the early 1920s gives a tantalisingly limited glimpse of the spending patterns of a woman with a healthy personal allowance of about £300 a year. ‘Mrs Pennyman’ of Stokesley, North Yorkshire, spent between one-third and one-sixth of her income on clothes, travelling regularly to London to shop at Harrods, Selfridges and Fortnum & Mason as well as patronising local department stores such as Binns of Middlesbrough and Fenwick of Newcastle.66

For those less fortunate there were various ways in which a middle-income woman could make her salary or dress allowance go further. This often involved financial juggling since it was the norm for women to settle accounts with stores and shops on an irregular basis rather than when the items were bought. Hire purchase was looked down upon so it was important to be able to meet one’s obligations to tradesmen when they became due. This financial balancing act is a constant theme in E.M. Delafield’s fictional classic, The Diary of a Provincial Lady.

Should like new pair of evening stockings, but depressing communication from Bank, still maintaining that I am overdrawn, prevents this, also rather unpleasantly worded letter from Messrs. Frippy and Coleman requesting payment of overdue account by return of post … write civilly to Messrs. F. and C. to the effect that cheque follows in a few days.67

Some middle-class women on limited incomes managed this juggling act of maintaining a higher-class front by buying good-quality second-hand clothes. Middle-class families would never have bought second-hand clothes from market stalls because of anxieties about cleanliness but even more of a concern would have been the stigma attached if one was seen.68 Yet, although none of the interviewees or Mass-Observation respondents admitted to it, there plainly was a thriving second-hand clothes trade among upper- and middle-class women.

There were two ways of going about shopping for second-hand clothes. First, one could buy and sell anonymously through classified advertisements in upper-middle-class magazines, in particular The Lady. Secondly, one could use the services of a dress agency. The reasons why women used the columns of The Lady were all too obvious. Middle-class women advertised wanting, typically, a parcel of clothes for a large family ‘trying to keep up appearances’.69 One explained that ‘having expensive taste, but greatly reduced income’, she would ‘be grateful if another would sell her exclusive wardrobe regularly and cheaply; only really good things; privately’.70 A 30-year-old widow, ‘income reduced’, writes plaintively ‘accustomed buy from best houses, would take entire wardrobe, day and evening, undies, from lady same age … must be moderate in price’.71

Phrases that crop up regularly, such as ‘originally expensive’ and ‘high class’ for example, show the keenness to keep up standards.72 Both sellers and buyers often proclaimed their status – ‘barrister’s wife’, ‘London lady’, ‘Titled lady’ – but more generally these advertisements were phrased using anonymous language. One can assume that the majority were from individuals although it is clear that professional clothes buyers also used the columns to find stock since occasionally the phrase ‘no dealers’ appears.

The Lady had started its classified columns from its first issues in 1885, offering free advertising for selling or buying ‘personal items’. It quickly became a money-making section of the magazine, often carrying nearly a thousand individual advertisements. While the majority were from sellers, there were those appealing to a middle-class clientele anxious to purchase from, as one advertisement put it, ‘a society lady only or maid to same, fashionable wardrobe’.73

By 1920, in addition to the lengthy columns of classified personal advertisements, small display advertisements were appearing in The Lady from the likes of Mr and Mrs Blandford of Gray’s Inn Road, offering to buy cast-off clothes. Since they claimed to have been in business since 1857, it was evidently an established trade.74 While middle-class women rarely used mail-order catalogues, the personal touch of a dress agency appears to have made it more acceptable.

It is difficult to estimate the extent of the dress agency business since discretion was an important aspect of this trade. Patricia Carr advertised her ‘Exclusive Dress Salon’ in Buckingham Palace Road, SW1, ‘now showing new and little worn Models bought from Society ladies [a] speciality’. It was discreetly pointed out that the ‘salon’ was on the first floor, thus eliminating any possible embarrassment for clients being seen through a ground–floor shop window.75

During the 1930s there were additional advertisements in The Lady for agencies such as ‘Titled Ladies Gowns’ at the ‘Regents Dress Agency’, which was ‘stocked with Right Clothes’.76 Cora Bee’s ‘Different Dress Agency’ offered ‘everything inexpensive but good’.77 One particular advertisement from the Regent proclaimed it had just purchased stock ‘from a well-known Marchioness … wonderful recent Model evening and day gowns, 2 and 3–piece suits, etc. Created by Vionnet, Chanel, Worn only once. Our price 2 to 8 gns. Orig. cost approx 40gns each.’78 Discretion was paramount – ‘Mrs Selway’ of Portobello Road claimed ‘courtesy, privacy and exclusiveness’ were her ‘dominating features’.79

Robina Wallis ran a postal dress agency, taking over her mother’s business in Tiverton, Devon, in 1929. The few records that survive throw a little light on this shadowy service. Extant correspondence shows that ‘Mrs’ Wallis, as she was known, advertised anonymously throughout the 1930s in The Lady magazine. She purchased clothes which she then sold through the post to customers. The address book listing the clients whom Mrs Wallis bought from reads like a copy of Debretts, an alphabet of aristocracy including the Countess of Arran, the Marchioness of Dufferin & Ava, Mrs Dudley Ward and Lady Victoria Wemyss.80 One customer claimed she had been given Mrs Wallis’s name by Buckingham Palace ‘with whom you have previously done business with’!81 The customer’s poor standard of writing suggests that the recommendation probably came from below stairs rather than above.

It is clear that the clothes Mrs Wallis bought from her aristocratic customers were generally months rather than years old since, on occasion, outfits coming from the Duchess of Roxburghe at Flores Castle were asked to be returned if unsold so that they could be worn again.82 These women evidently did not suffer as E.M. Delafield’s Provincial Lady had done when using a dress agency.

March 12th. – Collect major portion of my wardrobe and dispatch to address mentioned in advertisement pages of Time and Tide as prepared to pay Highest Prices for Outworn Garments, cheque by return … March 14th. – Rather inadequate Postal Order arrives, together with white tennis coat trimmed with rabbit, which – says accompanying letter – is returned as being unsaleable. Should like to know why.83

Letters to Mrs Wallis from women who bought her clothes confirm that the business covered a vast area of Britain, from Scotland in the north to London and the Home Counties in the south. It is evident from the financial details in the letters to Mrs Wallis that her purchasers were of a lower social status than her aristocratic sellers but they were invariably from the middle classes. Pleas for extended credit owing to dress allowances being needed to tide over bereaved relatives or extravagant sons are legion.84 ‘I don’t wonder you are angry and truly I would have sent you the money at once if I’d had it,’ wrote a customer from Cricklade who was regularly in arrears between 1932 and 1936.85

Businesses such as Mrs Wallis’s and the classified column inches in The Lady plainly thrived during the interwar period. The anonymous nature of the contact between buyer and seller was a perfect way of dealing with what otherwise could have been a socially awkward situation. The fact that evidence relating to dress agencies is so scant confirms that secrecy was paramount. These shops were never to be found on a high street displaying their wares in the window but were always discreetly up a flight of shadowy stairs. There was a sector of middle-class women who would rather ‘keep up appearances’ by buying second-hand quality clothes than consider the growing quantity of mass-produced styles that were coming on to the market.

The growth of mass production did mean that many women no longer expected to make most of their wardrobes themselves or, depending on their income, to have them made. In spite of the enduring popularity of fabrics from specialist stores such as Liberty’s, the sale of ‘piece goods’ – that is, fabric bought to be made up at home or by a dressmaker – had plummeted since before the First World War and departments selling ready-made items replaced those selling rolls of material.86 For example, after the First World War, Lewis’s department stores ‘placed far less emphasis on “yardage” and far more on “taste”’.87

Children’s wear was still mostly handmade. When Mrs E.E. was a young girl ‘a little woman’ came in twice a week for ‘half a crown a day and all her food’ to make her clothes.88 Mrs S.R.’s mother made all her and her sisters’ frocks but she remembers the thrill of buying her first ready-made outfit: ‘I thought I was really dressed because I had a bought dress on.’89 When she needed a tailored suit, she saved up from her wages of 15 shillings a week as a trainee hairdresser, and paid 12 guineas to have it tailor-made.90

Nevertheless, home dressmaking was extremely popular and was another way middle-class women improved the quality and stylishness of their wardrobe. Paper patterns were widely available and often given away with women’s magazines. Records from Arbery & Sons Ltd of Wantage, Berkshire, ‘drapers, outfitters and dressmakers’, contain lists of haberdashery items such as Sylko thread and petersham ordered regularly by in-house dressmakers and customers.91 Vogue ran articles suggesting ways in which ‘a girl with nothing a year’ could improve her wardrobe. These articles were visibly aimed at a readership from the middle classes struggling to maintain social standards. ‘At this time of year, when the rich woman is buying new items to refresh her winter wardrobe, the girl with nothing a year is dyeing, turning, or altering hers, and having just as good a time at it, especially when she appears in a camouflaged creation that fools everybody.’92 The success of homemade creations in fooling people that they were shop-bought is obviously hard to ascertain. It is significant that Mrs E.E. did not feel properly dressed until she was wearing a bought frock and would not have attempted any tailoring at home.

TAILORING TRENDS: CHANGING CHOICES FOR MEN

For middle-class men shopping for clothes was a quite different experience to that of women. Yet for them also, this was a period of change ushered in by mass production and the rise of a new breed of shops. There was still less flexibility in the buying of men’s clothes than women’s. Men did not have the option of going to ‘a little woman round the corner’ to have things made up. The male equivalent of the dress agency appears to be almost non-existent. Bespoke tailoring dominated at the top of the market.

Advice for men on what to wear still came from a tailor. There was no male equivalent of Vogue to be consulted and it was rare for newspapers to carry features on menswear. The ‘man on the street’ had little access to printed advice in the form of men’s fashion magazines. The short-lived Men Only, first published in 1935, was a lone exception in including a small section on men’s clothing called ‘The Well-Dressed Man’. The trade itself was well supplied with journals full of suggestions ostensibly on correct dress codes but obviously designed to boost business. Titles such as Man and his Clothes, Men’s Wear and Sartorial Gazette regularly carried articles with titles such as ‘The Influence of Clothes’, ‘Clothes and the Job’ and ‘For Better Business’.93

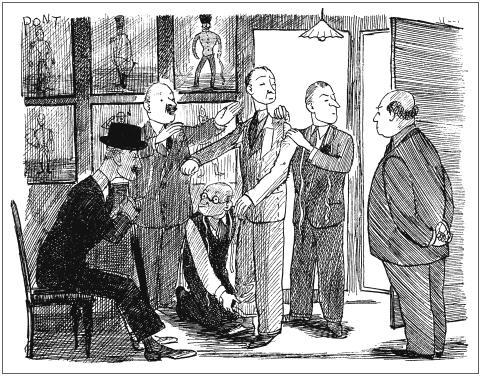

Pont’s cartoon was a particularly accurate parody of the ‘club-like’ atmosphere of the tailor’s fitting room where women were rarely welcomed. (Punch, 15 December 1937 © Punch Ltd)

For men of the lower-middle classes information increasingly came from tailoring assistants employed by chains such as Montague Burton’s and Hepworth’s. Burton’s published a highly confidential ‘Managers Guide’ (sic) full of advice on sales tactics. ‘Make your customer feel he is welcome and that you are anxious to please him,’ Burton’s encouraged their sales staff. ‘Avoid the severe style of the income tax collector, and the smooth tongue of the fortune teller. Cultivate the dignified style of the “Quaker tea blender” which is the happy medium.’94

Traditionally the world of the bespoke tailor was indisputably exclusively male. Little had changed since the pre-war Edwardian period when small tailoring establishments and gentlemen’s outfitters predominated. In the old-established businesses tailors encouraged their customers to rely solely on their advice. Not that the tailor’s advice was always sycophantic. One young man was warned that a double-breasted suit made him look as though he ‘was on board a yacht, i.e. dressing above his station’ while turned-up trousers would have made him look as though he ‘was ploughing a field’.95 Just as the customer desired the correct clothes, the assistant thought it part of his role as salesman to help maintain the status quo.

By the mid-1930s the traditional tailoring industries felt threatened by outside influences, specifically the burgeoning ready-made industry. In an article in 1935 subtitled ‘The frightful results of the intervention of Outsiders’, the anonymous writer damns ‘speculators … selling inferior goods’ and spurious advertising campaigns by multi-national retailers. Even the aristocrat’s valet is warned to leave the advice-giving to the bespoke tailor. The rallying cry from the industry was that there should be ‘definitely agreed codes and fixed standards, so that tailors could adhere to them and thus avoid conflicts of opinions offered and clashes of advices tendered’.96 This is obviously not an unexpected reply when trade might be threatened. Most upper-middle-class men were resigned to this system of control. One Mass-Observation respondent, ex-colonial Mr A., is typical of many who took their tailor’s advice. ‘He knows more about it than I do … manage to look reasonably presentable, so suppose it’s all right.’97

Tailors themselves had long been provided with style charts by trade magazines. In 1929 Austin Reed’s started publishing a publicity pamphlet for its customers called Modern Man, ‘a masculine magazine’.98 It was aimed at reassuring their customers on how shopping at their stores would confirm their superior class status with articles such as choosing the upper-middle-class necessities of ‘flying-clothes’ and ‘tropical kit’. By 1937 Simpson’s had published a chart for their customers in one of their publicity booklets detailing how an annual budget of £50 or £115 should be spent, down to the last set of studs. The two luxuries the higher-income man is allowed are a ‘bath gown’ and ‘6 silk handkerchiefs at 7/6’. Otherwise the difference is in quantity, and, to judge by the difference in price, in the quality of the goods listed.99

While advertising campaigns and shop displays became increasingly influential, the trade press suggested that ‘any customer who desires to see clothes as they look when worn has only to be observant of the well-dressed man that he meets in the course of a short walk down the street’.100 A few men did look to shop windows. Window displays had vastly improved, grouping items from various menswear departments to demonstrate a look rather than a single unit.101 One Mass-Observation respondent enjoyed ‘the more amusing advertisements, e.g. Austin Reed, Hector Powel’.102 A few made considered choices. Mr M., an engineer from London, wrote that he studied ‘tailors’ windows and other men’s styles and eventually decide on the kind of suit I want. I then go to the shop where I think I should get the best bargain and buy or am sold a suit similar to one I have chosen.’103

Some men left the choice of their clothes to their wives. A middle-aged man from Swindon admitted that his ‘choice of a suit [was] guided very largely by [his] wife’s strong prejudices in favour of respectability’.104 Nevertheless, the female influence was tacitly ignored by the tailoring industry that controlled menswear trends. Women were discouraged from entering the inner sanctum of the tailor’s fitting room and were only reluctantly welcomed into the male department store.

In contrast, general department stores were less successful at luring in men than women.105 Their percentage of total sales nearly doubled during the interwar period but was still only 6.6 per cent of the total market by 1939. Men, it was believed, did not enjoy such a frivolous occupation as shopping and even today one invariably finds the menswear departments of larger stores on the ground floor safely surrounded by exits for a quick getaway. In contrast, menswear sales by multiple shop retailers leapt from 9 per cent to over 30 per cent in less than twenty years.106 This included sales of other menswear garments such as shirts and ties.

Nevertheless, with the growth in numbers of department stores and multiples such as Burton’s, accessories such as ties and socks and items such as underwear were increasingly being bought by women. It was also a challenge to the men’s outfitters in much the same way that the stores stole business from the ‘Madam’ shops. This was particularly true in the north where Burton’s in Bolton found that ‘at least half the customers in the men’s department are women. This is in contrast to the practice in the South “and adds to our difficulties”’.107

Old-established tailoring businesses continued to service the upper-middle classes. However, the division of quality that had previously marked out the lower-middle-class man’s suit was lessening. There was far more choice on the high streets across the country. From 1920 to 1939 the number of multiple tailoring shops with fewer than twenty-five branches remained relatively stable, while these old companies had doubled the number of branches they had countrywide by 1939. Similarly, the number of larger firms competing for business increased slightly and tripled the number of outlets they had.108 During the 1920s new menswear multiples opened at a rate of two to three a week across Britain.

As with women’s clothing, new cutting techniques enabled the development of chains such as Henry Price’s ‘Fifty Shilling Tailor’ and Burton’s, which catered predominantly for a mass market, patronised by the lower-middle and working classes. Burton, who used as his slogan ‘a Man of Taste’, aimed just a little above his long-time competitor Price, with suits starting at 55 shillings. Since 50 shillings was estimated to be an average weekly wage, this was a relative bargain: residents of Lewes in Sussex, who did not have a nearby Burton’s, reportedly had to spend three weeks’ wages on a suit.109 In 1919 Burton’s had forty shops, of which half were in London and the non-industrial regions. By 1939 they had 565 shops, over 90 per cent of them outside the south-east.110

While the term ‘bespoke’ indicated a hand-stitched suit made by a ‘Savile Row’-style tailor, the term ‘tailor-made’ was most often used to indicate a machine-made semi-tailored suit bought from a chain such as Burton’s. The newest innovations were ‘ready-mades’, a term only just a little more acceptable than the earlier ‘reach-me-downs’.111 There was a stigma attached to buying these until well after the Second World War. A retailer recalled ‘one of our regular customers for years [was] the managing director of So-and-so’s across the street … a year ago he came in here to buy a suit and found himself standing beside one of his junior clerks … we haven’t seen him since.’112

Further up the social scale there was a relatively new marketing phenomenon – the specialist store aimed at middle- and upper-middle-class men, which sold a full range of menswear from suits to socks, combining the roles of tailor and outfitter. Stores such as Austin Reed, with what they termed ‘New Tailoring’, and later Simpson’s, bridged the gap between the two extremes of the expensive and exclusive Savile Row tailor and mass-production chains such as Burton’s.113 Whereas Burton’s modelled their stores on a style reminiscent of a gentlemen’s club, encouraging the illusion that their customers were entering a true tailor’s,114 Austin Reed and particularly Simpson’s were more forward-looking and introduced male customers to a style of shopping more familiar to their wives. This was not just a London phenomenon. Countrywide sales of the Simpson’s and Daks brands were ‘making Lancashire people more dress-conscious, more ready to follow the leaders,’ claimed a Bolton tailor.115

Research carried out by The Statistical Review of Press Advertising during the 1930s shows that Austin Reed regularly spent four times as much as their competitors such as Horne Bros in promoting their essentially upper-middle-class brand. Over 50 per cent of this advertising went into the national newspapers with another 25 per cent going into magazines. Aiming at men in the upper middle classes, Simpson’s of Piccadilly played on the success that would await those who dressed correctly. In 1938 they ran a series of advertisements, one of which read, ‘A rising architect yes, but what a pity he doesn’t get his clothes at Simpson’s’, the implication being that this man would be more successful if smartly dressed by the menswear store. Similarly they targeted the ‘member of the board’, the doctor with ‘a good bedside manner’ and the ‘Captain of the club’.116 All these jobs were high-status positions within the middle classes and so the clothing worn by men who held these jobs was a form of ‘uniform’ proclaiming their standing and disassociating them from the lower ranks within the same career structure. By contrast, Burton’s preferred direct marketing, sending out booklets to every man in a town’s local directory four times a year.117 The place of Austin Reed and Burton’s as brand leaders in their fields suggests that both these campaigns were successful.

There were noticeable regional differences in menswear sales patterns. Easter and August were the busiest times for the tailoring industry across Britain. In the north-west business peaked around June, a traditional holiday period.118 Menswear retailers from the Midlands northwards emphasised lower prices as opposed to variety.119 Austin Reed opened branches in Liverpool, Manchester and Preston during the early 1920s; the Liverpool and Manchester stores flourished but Preston floundered. Their first-ever market research campaign revealed that in Preston’s business area collarless coloured shirts outnumbered the formal white shirt by eight to one. This was in contrast to the figures in Liverpool and Manchester, where the ratio was virtually 50:50. Austin Reed duly closed the Preston store, accepting that the social mix in the town was not enough to sustain their middle-class business.120

A lower income did not necessarily mean a lower spend on clothing but this largely depended on where one lived. In 1926 Londoners needed to spend less on their clothes than those living in large towns, probably because more choice made prices slightly more competitive. In the lower-middle-class wage range those living in small towns with limited access to large department stores necessarily had to spend more on their clothes. In mathematical terms the provincial shopper felt the need to spend 1.5 per cent more of their income on clothes than Londoners did.121

To take one example from a man’s wardrobe, an evening suit was, for most men, likely to be their biggest clothing purchase. In 1929 Austin Reed advertised evening wear that would not ‘depart by a hair’s breadth from those standards which are implied by the very words “dress clothes”’. Such correctness came at a price. Jackets cost 4½ and 6 guineas, waistcoats, 30 shillings and trousers, 45 shillings. The longevity of such a purchase was emphasised by the fact that all the items could be bought separately and replaced ‘at any future time’.122 Although 80 per cent of clerks working within government, banking and insurance earned over £150 a year, salaries dropped slightly during the late 1920s and early 1930s and 6 guineas for one jacket would have been a major investment.123

It is not surprising that the expense but also the necessity of correct evening dress led to the growth of one of Britain’s most famous outfitting chains, Moss Bros. The company started by specialising in the hire of ceremonial dress from the turn of the twentieth century, and one general, Sir Ian Hamilton, found himself hiring a campaign uniform he had sold to Moss Bros thirty-six years before.124 This is a rare indication that there may have been a hidden second-hand menswear market as well though it was most likely confined to dress clothes. For example, clients of Moss Bros have always been able to purchase outfits that they have hired.125

The firm capitalised on the middle classes’ need for a correct but economically priced evening wear hire facility in the 1920s and 1930s. As store buyer Ethyle Campbell noted in 1939, Moss Bros served ‘those who have all the impulses towards gentility, but lack the necessary money to equip themselves in accordance with their real or imaginary status in life’.126 There had been a reluctance to use the facilities of a hire shop in the early 1920s. While the aristocracy had no such compunction, Moss Bros found the trade among the middle classes slow to start with.127 Ethyle Campbell explained:

This hush-hush attitude about the hiring of ceremonial garb is a peculiarly English one. The Englishman doesn’t really mind admitting that he is hard up. He doesn’t mind driving a shabby old car, wearing practically worn-out flannel bags, travelling third class by train, eating at cheap restaurants and risking wet feet to save a taxi fare … but – the ordinary, decent, reasonably truthful young man will shift, prevaricate, shuffle and lie sooner than admit that he has hired any garment.128

The social necessity for such outfits soon left many men with no choice but to hire rather than buy if they wanted to be seen in anything other than a poor quality suit. Men’s attitude to hiring their dress clothes is just one example of the angst that clothes-buying in the interwar years induced. Whatever the situation, at home, at work, on the golf course, even on holiday, dress mattered during this heyday of sartorial correctness.