FOUR

In Home and Garden

No matter what your circumstances may be, you cannot afford to neglect your appearance, nor must you ever forget that to look your best at all times is your duty – towards yourself and towards the man you married.1

Woman’s Own, October 1932

Woman’s Own did not mince its words in telling its female readers where their duty lay in 1930s Britain. It highlights the importance of the home in interwar society and the pressures to maintain correct standards even behind closed doors. For the majority of middle-class men the routine of their lives followed an established pattern. Their activities were neatly divided between work, domestic and social activities with clearly defined wardrobes to match. Their home was somewhere to come back to and relax in after a hard day’s work, an opportunity to escape the formality of the office – albeit one many were slow to take up. In contrast, most women within the middle classes stopped work on marriage and the home became their central domain.

In 1931 only 16 per cent of married women went out to work.2 Raising a family, running a house and neighbourhood society occupied their time and required flexible wardrobes to cope with changing demands throughout the day. The daily routine for a married woman depended on her family situation, the age of her children, her class status and where she lived. The 1920s and 1930s saw a spectacular house-building boom with housing developments spreading like tentacles along Britain’s newly-built arterial roads. Between 1919 and 1939 just under four million new homes were built, almost three-quarters of them for private buyers.3 This enabled almost 60 per cent of middle-class families to own or buy their own homes.4 By 1938 two-thirds of civil servants and teachers on salaries of £250–£500 a year had a mortgage.5 House-builders advertised for ‘families of good breeding’, aiming to keep each road to ‘a definite class’, and even asking for high deposits to keep ‘estate[s] select’.6 Since families were usually trying to ‘better themselves’ by buying one of these homes, the pressures on maintaining the correct social etiquette were considerable. Even codes of speech, such as saying ‘my husband’ instead of ‘my Bill’, had to be remembered.7

These suburban homes, usually built outside the major cities across the country but predominantly in the Midlands and south-east, brought with them a pre-occupation with the home environment. Events such as the annual Daily Mail ‘Ideal Home Exhibition’ recognised a new obsession with all things domestic. It was not surprising that the imagery of women at the Exhibition was ‘overwhelmingly middle-class – well-dressed, affluent and glamorous – and, almost certainly, married’.8

THE SERVANT PROBLEM

Organisations such as the Women’s Institute that focused on encouraging the domestic skills of their predominantly middle-class married members, thrived. This was in part because middle-class women were finding it increasingly difficult to get domestic help. Although servant numbers increased slightly overall during the interwar period, the number of individual family homes also grew, effectively creating staffing shortages.9 By the end of the 1920s the term ‘daily’ had come into common usage to describe the older, local woman who would come in and help with domestic work replacing the traditional live-in servant.10

Domestic staff were also becoming more demanding about pay, hours and social restrictions. Their new financial status showed in the clothes they wore, something noticed by Punch particularly in the early 1920s.11 It was also noted in the New Survey of London Life & Labour published in 1931:

With the better pay that she now commands the domestic servant is quite as well dressed as any others in her class … Well-cut ready-made garments of all kinds, artificial silk stockings and under-clothing, and fur-trimmed coats came within the reach of young ammunition workers during the war, and domestic servants now generally look on them as a necessary part of their equipment.12

Women from the lower middle class spent a great deal of time doing their own domestic chores. The designs of many newly built homes took this into consideration by ensuring that the cooking area of the home was not open to view, so that guests could not see the housewife working in her kitchen. In addition, advertisements in magazines such as Good Housekeeping and Ideal Home increasingly offered women new domestic appliances.13 Take-up of this type of equipment was slow but the middle classes were the first to buy them. Equipment with no direct relation to housework such as electric lights and radios quickly arrived in most households.14 But middle-class women benefited most from supposedly ‘time-saving’ appliances such as cookers and vacuum cleaners both in their usage and in their appeal to servants.15

Married women felt under pressure to maintain not only certain standards of ‘housewifery’ in their homes but also high standards of respectable dress within the home and neighbourhood. As Mrs P., a 36-year-old housewife from Surrey, explained,

I have no best or second best in the generally accepted sense. I have various frocks of which I have become very fond and as I choose patterns that don’t date I wear my frocks for three years on an average. I have no old clothes for wearing about the house liking to keep up to the same standard all the time. An overall protects them from dirty works. I don’t believe in any-old-thing for the home.16

The preoccupation with high standards of dress started before women got married. A telling quote comes from Miss Modern in 1932: ‘When a man looks for a wife,’ it said, ‘she must have a nice taste in dress … clothes are so important to a man’s success.’17 [My italics] Woman’s Own reminded married women that they must not let their standards slip after the wedding: ‘A certain loveliness … is born of a healthy mind and a healthy body, plus a fastidiousness about one’s toilet. This is the only beauty a man understands.’18

Mrs P., a 36-year-old housewife and Mass-Observation contributor from Surrey, thought that ‘one should look as nice for one’s husband and children as for anyone’ and coyly comments that she doesn’t ‘like to make too much effect on strangers – that can be inconvenient at times!’19 She continues by observing that:

one of the biggest differences in the matter of clothes now-a-days between my generation and those immediately before it, is the fact that women continue to take a pride in their appearance after domesticity has set in. My grandmother assumed cap, shawl and apron when she became married and settled down to be middle-aged. My mother never could bother about nice clothes, because she hadn’t the time with the children – and I take more interest in clothes and make-up now, after twelve years of married life, than I ever did when I was in my ’teens.20

The need to ‘keep up appearances’ in a variety of situations meant that most middle-class women felt they required a selection of clothes to suit varying occasions. Suitability was the critical dress criteria for Miss D., a 43-year-old unmarried organising secretary from London:

I am actually embarrassed if I find myself unsuitably dressed for an occasion but it does not worry me if other women have more fashionable or more expensive frocks. Having once satisfied myself that a garment is suitable, and having got ‘the feel’ of it, I do not consciously worry myself about its effect on others.21

Most middle-class women would change at least once in the day. For many this was a habit that did not change until after the Second World War. Mrs D.R.’s mother, from Lanarkshire, would wear ‘old things in the morning … with an apron on’ and change into a better dress in the afternoon.22 While fashionability was an important criterion in a dress, anything conspicuous or daring was considered ‘in very bad taste’ and ‘the mark of vulgarity’.23 The dictum of the time was: ‘Be not the first by whom the new is tried, Nor yet the last to cast the old aside.’24

Women at home regarded the clothes they wore in the morning as ‘work’ clothes. New electrical equipment such as irons and vacuum cleaners helped make housework a marginally less dirty job than it had been when carpets had to be brushed on hands and knees and irons heated up on a coal-fired stove. Not surprisingly, the iron and the vacuum cleaner were the most popular domestic items purchased during the 1930s. In the early 1930s less than 20 per cent of homes had an electric vacuum cleaner but by 1938 nearly 40 per cent owned one. Figures for take-up of irons were even greater and by 1936 70 per cent of homes had an electric iron.25

Advertisements no longer featured a maid using domestic machinery but the housewife herself, reflecting the increased involvement in the home of the middle-class woman. However, magazines such as Good Housekeeping rarely depicted women in anything other than a small dainty apron.26 Therefore there was little confusion between the maid’s apron – plain with an equally simple uniform dress – and that worn by the middle-class woman doing her own cleaning; hers was often decorated with flowers or trimmed with a coloured frill.

Advertisements for new electrical equipment for the home demonstrated their labour-saving properties for both mistress and maid. However, there was little confusion between the apron of the maid (left), plain with an equally simple uniform dress, and the apron worn by the middle-class woman (right) doing her own cleaning. Hers was often decorated with flowers or trimmed with a coloured frill and was ready to be whipped off as soon as the doorbell rang. (Hulton Getty)

Attitudes to aprons and overalls were changing as more women had to take on their own domestic chores. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s the wrap-round overall was associated with working-class ‘char’ women. Miss M., a 28-year-old pianist from Croydon, had a different attitude from her parents in such matters: ‘They hate to be caught by visitors if they are wearing old or working clothes, especially an apron. Myself I think a clean white overall is as pleasant as a frock and I do not mind who sees me. Most of my friends agree.’27 Many women chose to wear an apron that could be taken off as soon as the front door bell rang. As Miss M. shows, there was a need and a desire for respectability even within one’s own home. Worse would be to forget to take the apron off when ‘crossing the road to see a friend’.28 Even in the 1950s it was still considered the ‘height of bad manners and bad taste, very rude’ to answer the door with an apron on.

In the mid-1920s Mrs Gertrude Naylor (centre) poses with daughters Rita, Rose and at their feet Kay, elegant and confident of their middle-class status as the family of a Bradford industrialist. (Prof J. Styles)

OUT AND ABOUT

The housework done, a married woman’s day might continue with shopping trips, library visits, a trip to the cinema or appointments for tea. All required a degree of correctness greater than in the home. When Mrs P., a 36-year-old housewife from Surrey, went up to London once a week she wore her ‘smartest clothes’.29 Miss D., the 43-year-old secretary from London, found the need to change regularly put pressure on her wardrobe:

Except for three weeks holiday, there are few occasions when I can wear ‘any old thing’; hence my clothes are divided into formal, all-day, or country wear, rather than best and second best. Formal clothes are needed for ‘functions’, afternoon or evening, and social occasions; all-day clothes are those which do not look out of place in the office but can be also worn for informal evenings; country tweeds and a softer style of dressing is needed for week-ends in the country. Dress for formal occasions can seldom be more than two seasons old, after which it will probably be adapted for one of the other categories. In general coats and suits last three years, also dresses.30

What to wear for what occasion was a regular topic of female conversation. Female Mass-Observation respondents showed an acute awareness of the seemingly minor details of their appearance that sometimes exposed regional differences. Mrs T., a 30-year-old housewife from Otley, explained that in Yorkshire

it was considered fast to wear your best clothes for every day. Provincial middle-class people didn’t ‘dress up’ in their own homes. Even now my mother doesn’t ‘dress up’ to the same extent for a party in her own home as she does when she visits other people. She regards ‘dressing up’ as a compliment to her hostess but it would be showing off if she dressed to the same extent when she was receiving guests.31

This attitude reflects the general view among the middle classes that to be too fashionable was to border on the ostentatious or vulgar. The ideal middle-class woman should be, according to London dress buyer Ethyle Campbell, ‘just a little behind the current fashion – weeks, not years – rather than quite abreast. She would then be well turned out in every sense of the word without being conspicuous.’32

In John Bull at Home, written in 1933, the author Karl Silex suggests that the reason why Englishwomen were ‘smart’ while Frenchwomen were ‘chic’ is that Englishwomen viewed their clothes as a form of uniform.33 A traditional rather than ultra-fashionable style of costume or frock brought a certain reassurance with it. Established styles offered a social safety net. Even in maternity wear, women were encouraged to ‘conform’ as much as possible ‘so the wearer doesn’t look different to other women’.34 Specialist maternity wear was hard to find and pregnant women usually had to make their own outfits or use a dressmaker or tailor.

The key to this British style of correctness was ‘good taste’. As medical researcher’s daughter Eileen Elias pointed out, ‘“taste” was something I was very careful about … I had no clear idea of what it was, but I knew it was terribly important.’35 Harold Nicolson wrote in 1930 that ‘the people who are the most lavish in maintaining the ideal of good taste and in decrying its opposite are in most cases people who are not very certain of their own sense of values’.36 During this period the wearing of correct and ‘tasteful’ clothing alleviated a woman’s social anxieties. Mrs K., a housewife from Yorkshire, echoes the sentiments of Miss D., a secretary from London, admitting, ‘If I’m not well-dressed – suitably for the occasion – I feel self-conscious. When I know I look “right” I can forget myself.’37

The desire for anonymity lead to a definite feeling of ‘anti-fashion’ among the middle classes, the irony being that it forced them to change their appearance so that they could disassociate themselves from anything that might be considered ‘too cheap, too expensive, too formal, too slovenly, too old-fashioned or too trendy’.38 Older women, for example, often took to wearing black indefinitely after the death of their husbands. Mrs E.E. of Pwllheli remembers her mother dyeing all her clothes after she was widowed.39

The agonies women went through in deciding what to wear for what occasion were rarely more complicated than in the interwar years. While styles appeared to be less rigid than before the First World War, there was still a complicated code of dressing that had to be adhered to. (Punch, 13 January 1937 © Punch Ltd)

The younger the person the less concern they showed for ‘keeping up appearances’ though this did not exempt them from social awareness. Miss M., a young girl from Romford who describes herself as middle class, would not be seen locally with ‘a shiny nose or laddered stockings or shabby coat’ but was far less worried about her appearance away from Romford or at home. Sagely she explains that ‘this points to my taking care over myself only to impress the people I know … “No-one knows me around here” exempts me from taking pains.’ Within the home, the divide between the generations on matters of fashion was becoming more noticeable. Miss M. mocked her parents for thinking that short skirts were not ‘nice’. ‘The not-nice attitude is typical,’ she wrote, quoting other aphorisms of her parents such as ‘nice girls don’t wear slacks in the street’ and ‘nice men’ don’t wear ‘brightly-coloured suits’.40

CLEANLINESS AND CLOTHES CARE

There was no debate over matters of cleanliness. It was not just a vital part of daily living but had to be seen to be so as well. Because of the atmosphere of ‘niceness’, titled ladies such as Lady Troubridge warned in magazines that the dangers of poor dress care could be far-reaching: ‘Many a “marriage will not take place” notice has been traced back to a dusty black velvet frock.’41

E.M. Forster cruelly said that the middle classes of this period smelled, but personal hygiene was a constant battle at a time when even many upper-middle-class homes had only the most basic of washing facilities.42 The ‘stink of unwashed humanity’ was so great in one cinema, according to a chemist in Lancashire, that he was forced to buy more expensive tickets in order to avoid it.43 Attitudes to hygiene varied between the sexes. For most men, it was accepted that ‘a man should not seem to have tried consciously to do anything about his appearance other than the minimum demands of hygiene’.44 Yet the standards of a civil servant from Yorkshire who prided himself on his tidiness are typical:

I like to keep suits on coat-hangers while not in use – I always fasten the top waistcoat button and the middle jacket button when on a coat-hanger. Press occasionally, I brush weekly. Other clothes – I rotate on 3 shirts, wearing one for week; clean collar every other day, clean handkerchief every day in winter; clean socks every other day. Vest I changed weekly, I don’t wear pants; pyjamas I change fortnightly.45

Established styles offered a social safety net, as shown by the Davies family from Crosby in Lancashire, gathered for a family christening; all the women look relaxed and ‘suitably’ dressed. (Mrs A. Sharp)

Women were increasingly becoming aware of body odour through magazines. Removable dress shields were sewn into clothes to protect them from underarm staining. Basic deodorants such as ‘Odorono’ could be bought but were frowned upon by the older generation. Amazingly, a book published in 1936 called The Modern Woman. Beauty, physical culture and hygiene, with subjects ranging from corsets to constipation, managed not to mention perspiration once.46 ‘Ladies’, believed the elder relations of Miss H., a 37-year-old housewife from Blackheath, ‘do not perspire so deodorants are not a necessary adjunct to the bathroom and it’s perfectly horrible to wear protectors in one’s dresses’.47 Instead, toilette water or ‘scent’ – the word ‘perfume’ was thought common – were used to mask body smells to some extent.

Clothes care was important to both sexes and every middle-class home had a clothes brush on the hallstand ready to brush down a suit or costume and a darning ‘mushroom’ in its mending box.48 An indication of this perceived respectability was intimated by the requirement suggested by Ethyle Campbell that a woman should ‘have a fresh, wholesome appearance, turned out in such a way that it subtly conveyed, without investigation, that her underclothing was spotless’.49

Achieving spotless underclothes required careful cleaning. In 1938 only 4 per cent of UK households owned a washing machine.50 Laundry services were still relatively cheap but clothes cleaning and repairs were still one of the largest chores for the middle-class woman either to cope with herself or oversee. For many middle-class women evening leisure involved some element of darning, mending or knitting for the family while listening to the radio.51

With few homes having any form of central heating, families wore clothes in the home for warmth as much as for comfort or elegance. Knitting was therefore a practical and valuable craft for women to master. More than a hobby, it was a way of economically expanding the family wardrobe. Great skill was often required to create the complicated patterns that were so fashionable. With so much knitwear made at home, broadcaster René Cutforth claimed it was ‘a notable stroke of the universal one-upmanship to own a genuine Fair Isle sweater’.52

POWDER AND PAINT

Another area which caused sparks to fly between the generations was that of make-up. The use of cosmetics by middle-class women slowly developed during the 1920s. The older generation and the more staid middle classes still considered lipstick taboo until much later. They considered vulgar not just the use of it, but its application in public. In 1925 Mrs Forester wrote in Success Through Dress, ‘Well-bred women do not so often offend in this prospect, but it is a pity our ultra-modern girls seem unable to grasp the fact that the use of the lipstick in public is not all a question of morals, simply of taste.’53 Make-up was problematical for the young female, as this verse from 1927 shows:

A powder-puff or a shiny nose – a shiny nose or a powder puff?

A problem this, it seems to me, on which some girls cannot agree.

From good taste it is very far, to make up like a cinema star.

But you can’t look pretty with a nose like sun,

So my puff will always be my good, staunch chum!54

By the 1930s, when a shiny nose was deemed ‘unpardonable’, a matt-powdered face was the only acceptable face for a woman. Miss M., a student from Romford, recorded her friends’ comments: ‘Yes, my dear, she’s quite nice looking, I suppose, but her nose! Hasn’t she ever heard of powder?’55

By the late 1920s the increase in the use of cosmetics was inexorable. Within the middle classes, while public use was still associated with low morals, in 1930 magazines were cautiously acknowledging that some use of cosmetics was inevitable even for job interviews. ‘You may need a little powder, but if so, choose it with care and apply it with discretion. As for lipstick, if you use it at all, remember that art lies in concealing art.’56 In 1932 Godfrey Winn, writing in Miss Modern, was outraged when the Bank of England banned its female employees from wearing make-up. ‘The majority of business men, from chief down to office boy, delight in the pretty, varied clothes and the lovely (though artificial) complexions of the women members of staff. … they introduce glamour and romance into our humdrum routine.’57

For many girls a dance or theatre trip was the first opportunity they had to wear any form of make-up though cosmetics were still frowned upon by the older man. ‘Ladies now do not hesitate to powder their noses and rouge their lips and even comb their shingled locks not only in public places but at one’s private dining table,’ complained a correspondent in The Times. ‘Surely the proper place is in the dressing-room and not where it causes offence to others?’58

Similarly, some young men were suspicious of cosmetics. ‘I am always over-awed by splendid coiffures and elaborate make-up,’ confessed a 24-year-old local government clerk from Sutton in Surrey, ‘[and] aim at a girl who I can safely lay hands on without anything coming to pieces or smearing.’59 The too obvious wearing of lipstick and rouge was seen as vulgar. This sort of snobbery was confirmed even by a young middle-class girl who was interviewed for Mass-Observation outside the Streatham Locarno in South London; she said, ‘I don’t like the girl[s] in there … [they are] too heavily made-up.’60

Early 1930s advertisements aimed at married women show that many men also disapproved of their wives wearing make-up since it might make them look cheap. Cosmetic advertisements tactically acknowledged this male reticence. ‘There’s one thing even a loving husband won’t forgive … a cheap, painted look!’61 The dilemma was that fashionable women were increasingly using make– up and therefore not to use it could be seen as being distinctly behind the times.

Make-up was a particular cause of disagreement between the younger and older generations. Miss H., a 21-year-old hospital almoner’s clerk from Bromley in Kent, had problems getting her parents to accept her wearing of make-up:

My people are reluctant but willing to accept any fashion, but lipstick is a veritable red flag to a bull in my home! It is, I am told, muck, horrible and never used when they were young and definitely not necessary. I use lipstick and make-up in moderation, if applied carefully looks well, and certainly gives me added self-confidence.62

But given the popularity of the glamorous film stars seen every week at the cinema, it is not surprising that the popularity of cosmetics was unstoppable. Manufacturers were quick to respond and there was a giant leap in advertising expenditure on face powders in the early 1930s. Within two years spending had leapt by 50 per cent from £18,315 a quarter to £27,606. The top company, Tokalon, spent over £3,500 in the national press in September 1934 alone.63 This was an enormous amount considering that it was more than the total spent by eighteen competing firms advertising perfumes in one quarter in 1933.64

Advertising on face powder continued to grow, increasing by nearly 40 per cent in one year.65 In late 1936 magazines carried 60 per cent more advertisements for lipstick than in the same six months of the previous year.66 While the consequences of impending war during the first half of 1939 must be taken into account, it is clear that advertisers were reacting to increased demand for their products.

By the end of the 1930s only the older generation still considered make-up vulgar. The complication remained that a shiny nose and laddered stockings were also thought of as ‘inferior’.67 Mrs H., a 37-year-old housewife from Blackheath, came from a family who disapproved of cosmetics. Her aunt used books of Papier Poudré, pocket-sized leaves of powder-impregnated papers for blotting, ‘so thinks she has evaded the daily sin of powdering her face’.68 In 1939 many older women regarded ‘unusual hats and lipstick as an outward sign of complete lack of morals and sense and no capabilities for business’.69 However, figures detailing advertising spending on lipstick and rouge between 1935 and 1939 show they were fighting a losing battle.70

Magazines for the middle classes such as Good Housekeeping were important influences in middle-class women’s lives. When it came to writing about cosmetics, they concentrated their editorials on the less frivolous aspects of beauty care such as weight control and anti-ageing exercises. In 1931 Good Housekeeping ran a light-hearted article called, ‘Do Women Dress to Please Men?’, berating the ‘habits of modern woman, her paint and powder, her reddened nails … and plucked eyebrows … [do] many women realise how deeply men are revolted by some of their habits?’.71 This reaffirms the pressures women within the middle classes were under to remain feminine without incurring the dreaded vulgarity that too much make-up might bring them.

A survey published in Good Housekeeping in 1930 had revealed that the use of obvious make-up was still frowned upon and ‘very much [in] a minority among women of the middle classes’. Only 20 per cent of their readers used lipstick, 7 per cent rouge and 5 per cent scent. Yet few used no make-up at all, only 7½ per cent.72 In 1935 a feature called ‘What Price Beauty?’ revealed that whereas a provincial typist might be expected to spend just over £3 a year on her cosmetics budget, Good Housekeeping’s average reader would spend £8–9 a year to cover rouge, lipstick and face powder plus visits to the hairdresser and beauty salon.73 This appears to confirm Robert Graves’s much-quoted observation that the course for the acceptance of cosmetics went ‘from brothel to stage, then on to Bohemia, to Society, to Society’s maids, to the mill-girl, and lastly to the suburban woman’.74 Rather than trickling down the social ladder, make-up bounced through the various different groupings before finally coming to rest among the staid middle classes.

MENSWEAR AT HOME

Unlike housewives, whose weekend wardrobes were on the whole the same as their weekday wear, most middle-class men did have separate clothes that were worn only at weekends. Many men felt constrained by the clothes they had to wear for work and young men in particular were relieved to be able to wear more relaxed clothing when they were not working. Mr H., a 17-year-old articled clerk from Sunderland, expressed how many felt: ‘Apart from office occasions, I usually dress in plus fours or something which leaves the office behind, something which I feel free in.’75

Yet whereas women usually changed during the day into a smarter ‘afternoon dress’ for socialising, a man’s wardrobe would only change completely when the working week ended. Leisure did not necessarily start immediately when they returned home from the office. A man might take off his jacket and put on a cardigan or jumper, but in general he would keep other items for weekend wear.

Men were therefore not free from social dress codes in or around their own homes. For example, although there was a tongue-in-cheek call for more colourful braces through the columns of The Times in 1932, braces, along with sock suspenders, were expected to be invisible in polite society.76 The necessity for men to have three-piece suits was in part to use the waistcoat to cover up braces which were still required to hold up suit trousers. But to display them even in their own home was ‘low’ and ‘common’.77

The tale of a man being berated by his wife for sitting in his garden in his braces, reported in The New Statesman and Nation in 1938, is revealing. Her use of words such as ‘uncivilised’, ‘country bumpkin’, ‘indecent’ and ‘bad example’ show the strength of feeling that such an action induced. This woman was not concerned with the styling of her husband’s outfit but with what the neighbours would think if they saw him. The author acknowledged that there was what he called ‘a social vendetta against braces’ publicised in the Sunday Express and led, he claimed, by women.78

Since it was considered extremely ‘bad form’ for a respectable man to take his coat off and reveal his braces, it is not surprising that men from the middle classes were reluctant to take their jackets off in public, whether through pressure from their wives or from their own social conscience, however informal the surroundings might be. The relaxed attitudes of the ‘rough’ working-class man in his shirtsleeves were anathema to the ‘Pooterish’ respectability of the lower middle classes. The less socially confident could easily slip up by misjudging their ‘off-duty’ clothes. When a Scotland Yard detective joined the well-to-do Newby family on their boat on the Thames, he was damned for taking off his black suit jacket and revealing ‘a thick flannel shirt and rather grubby braces’, and was forever known as ‘that fellow who wore braces’.79

Many middle-aged men in particular did not feel relaxed without a jacket even in their own homes. Playwright John Osborne’s grandfather was ‘always dressed … as if ready to go out at any moment’.80 Even on retirement, men did not necessarily discard formal outfits completely. I cannot remember my own grandfather, a retired economist, wearing anything other than a three-piece suit daily until his death in 1957.

Mr A., a 31-year-old married retail chemist from Colne in Lancashire, owned one business suit and five suits all ‘worn in leisure time’: a one-year-old grey lounge suit, a four-year-old navy blue suit, a three-year-old tweed suit, and a six-year-old plus-four suit and a sports suit, both worn mostly for holidays. ‘I like the right thing for the right occasions,’ Mr A. commented. ‘I do not wear sport suits for business or formal occasions, or indoors generally.’81 And as Mr A., a 23-year-old journalist from Chelmsford, said, ‘There is a considerable difference between my dull workaday appearance and my appearance at weekends and other times when I do not have to be about our office.’82

Mr R. of Tamworth was unusual in changing immediately he got home into what he termed ‘free-and-easy garb’:

I like as much freedom as possible in the matter of clothes, and wear sports attire with open-neck shirt whenever possible, even in winter. In summer I wear shorts and sleeveless shirt at home, in the garden and when hiking and cycling (my favorite [sic] recreations). On returning home each evening I always change into this free-and-easy garb, and I never wear anything else at weekends. I hate ‘best clothes’ for Sundays and am usually more unconventionally dressed on that day than any other.83

Plus-fours and patterned socks for weekend wear were popular during the 1930s even for those who never played golf. Mick Borgars and his friend, both from Wiltshire, look relaxed with their contrasting styles of leisurewear. (Mrs E. Baxendale)

Many men felt uncomfortable without the armour of a formal suit jacket around them, even in their own homes. According to his daughter, this is a rare photograph of her father, Richard Williams, an accountant with the Liverpool Gas Company, wearing a jumper rather than a jacket in 1935. (Mrs A. Sharp)

In the 1930s most men would have had knitted for them a sleeveless ‘vest’ worn instead of the formal waistcoat, the third part of the three-piece suit. The adaptability of patterns was part of their popularity, as can be seen from a knitting pattern for the ‘David’ pullover, possibly named after the family name that Edward VIII was known by. It was described as a

serviceable pullover, knitted in a neat vandyked design, [and] is suitable for the older man no less than for the younger. Made up in a fawn or grey shade of wool, it would be right for wearing during working hours; or, knitted in one of the lighter colourings, it would be useful for wearing at tennis or on other sports occasions.84

The idea of the ‘Sunday Best’ was rapidly dying out within the middle classes.85 At home at weekends, particularly on Sundays, since many men still worked on Saturday mornings, there was an opportunity to escape the formal suit. The attitude of Mr B., a 26-year-old clerk from central London, is typical. ‘At week-ends I wear plus-fours or an old suit or grey flannel trousers and sports coat if there are visitors at home. If not, old trousers and khaki shirt for gardening, etc.’86

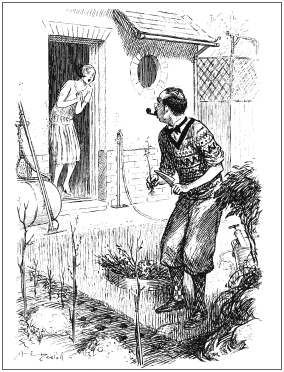

With many families owning their own home for the first time, gardening became a popular hobby for many men in the 1920s and 1930s. Old lounge suits were often kept for pottering around in but popular fashions such as plus-fours and patterned knitwear were regular weekend wear as well. The winged collar is a satirical dig at the Englishman’s seeming inability to reject formality completely. (Punch, 29 April 1925 © Punch Ltd)

Old suits were frequently kept for wearing while gardening.87 Cartoons allude to the fashion for middle-class suburban man even to wear golfing clothes while gardening. Gardening was a popular hobby encouraged by the design of the new

suburban house which gave every householder a back garden and often a front garden to care for. The man of the house did most of the work and most male respondents mention keeping old clothes for gardening.

Mass-Observation respondents knew what was thought correct for men to wear at weekends. Miss H., a hospital library assistant from Liverpool, was quite clear that it was not acceptable to her for a man to wear an open-necked shirt in the street. ‘This can be obviated by filling in the space with a scarf … Also it is not “done” to wear a lounge jacket with flannels – a blazer is the correct thing. Then there is the fact of not doing up the bottom button of your waistcoat.’88

In spite of the fact that the term ‘sports’ clothes was used for informal clothes not necessarily worn for a particular sport, much of men’s leisure clothing did reveal the influence of participatory sports. Virtually all the men questioned by Mass-Observation mentioned ‘sports’ jackets and flannels in their wardrobe listings. Mr A., the young journalist from Chelmsford, wore what he called the ‘usual week-end wear, unless hiking or biking is to take place’. His weekend wear comprised grey flannels, ‘Kantabs’ (a brand of flannel trousers) and a dark blue blazer with his school crest on the pocket, the typical middle-class system of branding. Mr A. also owned a plus-four suit, which was ‘rather dirty’ and had been ‘re-seated with material from similar previous plus-4 suit’. This he wore ‘only if hiking and biking, usually with a blue-grey roll-neck pullover’.89

The origins of plus-fours are obscure. Clearly related to breeches, the ‘four’ is most likely to indicate the number of inches below the knee these garments should correctly be worn at, a practical and, as it turned out, fashionable alternative to tucking one’s trousers into one’s socks to prevent them getting wet or muddy when following country pursuits such as shooting and, of course, golf. They were looser and longer than knickerbockers, which had traditionally been worn with the Norfolk jacket since the mid-nineteenth century.90 The high point of the plus-four suit was around 1927, prompted by the Prince of Wales’s passion for them together with checked socks and Argyle jumpers.91 Although The Drapers’ Record mentions record sales of plus-four suits in 1930, they gradually fell out of fashion for golf after that to be replaced by the traditional trouser style.92 By the mid-1930s the figure of the ‘knickerbocker glory’ was a regular object of ridicule in the satirical press.93

Much as the tracksuit and trainer wearer of today may never have set foot inside a gym, plus-four trousers were often worn by men who had rarely, if ever, swung a club. Yet it was a popular item of menswear particularly in the 1920s. Many Mass-Observation respondents still owned a pair for ‘weekend wear’ in 1939, clearly reluctant to part with a garment that was comfortable if outdated.94 Mr M., a 30-year-old married man from Ayrshire who worked in the steel industry, owned a plus-four suit he had bought seven years previously for golf. ‘Now that I’ve stopped golfing I use the trousers for cycling along with a leather jacket that I had for golf.’95

British middle-class men seem to have remained untouched by the new breed of American male film star who successfully wore a smart but casual look. Women’s magazines bewailed the fact that few men looked to the cinema for dress guidance while acknowledging that ‘too much obvious interest in his clothes on the part of any man is not a trait which is regularly admired among men’.96 Much as women may have wanted their sweethearts or husbands to emulate a certain film star’s style, the truth was that in Britain, as in America, women’s opinions appeared to have little impact on manliness or men’s dress, especially with regard to what they wore at home. As many think is still the case, during the interwar years, British men did not take easily to ‘casual’ dressing.