SEVEN

Everything to Match

Never wear an outfit until you have collected everything, yes everything, to go with it – hat, shoes, gloves, handbag, scarf and even a special umbrella to match.1

Miss Modern (1936)

The advice from Miss Modern magazine in 1936 was clearly aimed at young women, but for men and women alike, young and old, accessories completed an ensemble yet their importance was often out of proportion to their size. They were frequently vital emblems of correctness and respectability. Seemingly minor items such as gloves, ties, braces or hats, if incorrectly chosen or worn, had clear social significance and could betray a person’s lack of breeding.

Accessories can generally be divided into those that can be justified on the grounds of necessity and those that can be seen only as fashion items. A few, such as hats and gloves, fall between two stools; they were often needed but, for women, they were fashion items in their own right. As broadcaster René Cutforth pointed out, they comprised ‘a whole armoury of paraphernalia, cufflinks, cigarette holders, cigarette cases, studs and tie pins … and most of these gadgets were counters in the class game’.2 They were items that Mr D., a 27-year-old insurance agent from Hove, with typical middle-class reserve of the period, termed ‘anything unnecessary in dress’.3

THE TIES THAT BOUND

There was one accessory that men could not avoid wearing and that was the tie. To do so was to be associated with the plebeian collarless worker. For the middle classes there is little doubt that P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves was correct when he stated that ‘there is no time … at which ties do not matter’.4 While ties were often seen as tyrannical objects, associated with the strangulating stiffness of collars, the British male of all classes was extremely reluctant to relinquish them even at leisure.5

For the man from the upper middle classes in particular, the tie was part of the coded language of his social group. In the wardrobe of every upper-middle-class man would have been at least one striped tie denoting the key rites of passage to his current social position – public school, regiment/ship, sports club, gentlemen’s club – all were represented by prescribed sets of coloured stripes. Mr B., a 27-year-old undergraduate, owned only two ties. Significantly one was the ‘club stripe of a club I belong to and [the other] one quiet blue – worn alternatively’.6 Another Mr B., Stanley Baldwin, although his son insisted he did not ‘dress to impress [and] would never wear his old school tie’, did admit that he relished ‘wearing the yellow, red and black striped tie of the I Zingari Cricket Club when out of London’.7 This exclusive club, formed in 1845, boasted one of the first recorded ‘striped’ ties.

The fashion for wearing ties with affiliations started in earnest at the turn of the century. The majority of British public schools established their striped-tie colours in the Edwardian era, and they were often linked to the establishment of ‘Old Boys’ societies. This was the period when the majority of the regimental, school and university tie designs were registered with a few select companies such as T.A.M. Lewin of Jermyn Street which had been established in 1898. Those who had not already done so created their designs in the 1920s and 1930s.

A tie manufacturer’s pattern book of the period shows 183 different combinations of silk stripes, ranging from No. 1, the Guards (maroon and navy), to No. 183, the Royal Corps of Signals (pale blue and green with a narrow navy stripe). In between were other military organisations and Old Boys clubs such as the Old Carthusians of Charterhouse public school (navy with narrow grey and maroon stripes) and the Old Bedfordians (navy and grey).8

From the 1930s many public schools such as Sherborne and Berkhampstead had ‘country’ and ‘city’ colours, particularly when the original colour schemes were bold. The ‘city’ version would have smaller, more discreet stripes on a black or navy background.9 Subtle variations were also available. Lewin’s designed a tie for those who went to school at Harrow and then on to Christ’s College, Cambridge, combining the colours of both school and university college. In addition, firms like Lewin’s and Benson & Clegg produced ties with crests, bow-ties, blazer badges, hat bands, cufflinks, cravats and scarf squares all with the appropriate colour or crest. Ties with crests on were rare during this period and did not become popular until after the Second World War, possibly connected with the large number of ex-service organisations which chose symbolic regimental emblems for their crests in preference to stripes in the late 1940s and 1950s.

In 1968 it was still possible for dress historian James Laver to categorise 750 different ties with club, school or career associations from sporting clubs to the Inns of Court.10 Thus by the late 1930s the middle-class man would have had a small but distinct choice of ties to wear signalling to others his educational background, social standing and sporting interests.

To the untutored eye many of the patterns seem indistinguishable but this was the most classic and subtle form of social exclusion. With the lounge suit becoming more universal, the upper middle classes clung tenaciously to any distinguishing factors that could maintain the class divide. The presumption of any man stupid enough to wear a tie to which he was not entitled naturally earned him social disapproval. In 1925 Ernest Hemingway spotted F. Scott Fitzgerald in Paris wearing a Guards tie with the distinctive – and distinguished – navy and maroon stripe. He claimed to have bought it in Rome.11

In the 1930s Apparel Arts, an American menswear trade magazine, published an article detailing the thirty major British regimental colours.12 The Guards tie was a style that had sold ‘like hot cakes’ in America once Edward, Prince of Wales, who of course was entitled to, was seen wearing it. In Britain Punch pointed out the humour of all and sundry being able to buy ‘club’ ties in a poem entitled ‘Gents’ Smart Neck-wear. Lines inspired by the spectacle of a number of club-ties in the windows of a sixpenny “cash-and-carry” store’:

How deep a debt we owe to Mr Woolworth

(I speak in tropes: his rule is strictly cash),

Who for our humble sixpence gives such full worth,

Enabling one and all to cut a dash

(It matters not with howsoever thick a mist

Obscurity enwraps their earlier years)

Either as Old Etonian or Wykehamist

On Britain’s proms and piers!

Incogniti, Crusaders, Bacchanalians,

See how they flaunt their richly-blended hues!

Hawks, Butterflies, Authentics, Old Borstalians,

I Zingari – you’ve only got to choose;

No need to face the hazard of rejection

Or year by year to pay immoderate subs;

At sixpence each you have a wide selection

Of all the smartest clubs.13

In 1933 dress historian Doris Langley Moore confirmed the truth behind this poem and showed how easily the naive shopper could be ensnared:

In a certain ‘mammoth store’ we saw a counter covered with ties, tobacco pouches, and other articles, made up in well-known combinations of colours, and hanging about them a show card bearing these words: ‘School and Club Colours – Always Fashionable.’ And there we observed a number of men innocently choosing their stripes.14 (Original italics.)

Even in the early 1950s, when George Thomas took his seat as a young Labour MP in the House of Commons, he was accosted by a Conservative Chief Whip who accused him of wearing an Old Etonian tie. Thomas, unabashed, assured him he had bought it from a Co-operative Society store in his Welsh constituency of Tonypandy.15 Mindful of this sort of confusion, a few organisations insisted on identification before purchase. Ogden’s, official suppliers to the Sir Joseph Williamson’s Mathematical School, Rochester, Kent, would only sell to registered names.16

For those excluded from this ‘club tie’ coterie, which meant the majority of lower-middle-class men, their main concern was maintaining an image of respectability through the appearance and cleanliness of their shirt collars. ‘Sonny’ Farebrother, a character in Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time, hoped to make his fortune with a machine to turn stiff collars so that both sides could be used, thus ‘reduc[ing] laundry bills by fifty per cent’.17 The failure of his machine was matched only by the disgust of his snobbish friends at such a suggestion.

During the 1930s men in the middle classes had a choice of collar style for day wear. However, the older generation were reluctant to relinquish the formality of the pre-First World War era and many retained the winged collar. This encouraged a look of gravitas they were unwilling to part with. Younger men tended to stay with the separate stiff collar throughout the 1930s for reasons mainly of economy rather than comfort. It was cheaper to launder a collar rather than a complete shirt. The shirt with an attached collar was acceptable for informal wear and was quickly taken up by the young in preference to the stiff collars their fathers preferred. A popular style had long points which were secured under the tie knot with a gold pin. ‘It was a social error,’ recalls broadcaster René Cutforth, ‘if this tiepin had a twisted bar or a round bar or a silver bar: it must be flat and gold.’18

Stiff collars looked dated by the 1930s but the older generation were reluctant to give up a look to which they felt accustomed as shown by two generations of the Bunce family from north London. The pater familias, complete with hat in hand (standing, right), prefers a more traditional look to his middle-aged sons. (Mrs E. Baxendale)

Whatever the style, clean collars were imperative, dirty collars suggesting a lack of respectability, a cliché going back to the eighteenth century at the very least. The older generation were not about to abandon a look to which they were accustomed, despite the acknowledged discomfort of the starched collar. In many ways, just as the corset had given women a bearing that was easily visible and definable, so the stiff collar gave a man a sense of uprightness which could be equated with dignity. Certainly anything less would not be considered except by a younger generation.

The abolition of the stiff collar was one of the main proposals in the ‘manifesto’ of the Men’s Dress Reform Party when it was established in 1929. They were not the first to tackle this issue in the 1920s. In 1926 the Anti-Collar League had met in Paris. They knew they wanted to abolish the starched collar but, according to press reports, could not agree on what to have as a substitute.19 The MDRP in contrast wanted to replace the collar with a fixed or ‘soft’ collar to be worn without a tie. The question of doing away with stiff collars for men was also fundamental to their ethos. By advocating the abandonment of not just separate and stiffened collars but also ties as well, they alienated many men.

Ten years later, in 1939, a military man from Eastbourne, Sussex, admitted that the use of ‘loose collars’ would be more hygienic but insisted that ‘the weight of conservative opinion’ against this meant that he did not ‘consider the question one to be pursued’.20 It was the younger generation who were taking the lead as usual. A 22-year-old bank clerk from Wiltshire was typical in not wearing stiff collars, ‘a departure’, he admitted, ‘from my father’s tradition’.21

THE PATH TO RESPECTABILITY

The pressure on women was to obtain matching accessories and in particular shoes and bags. The language of shoes (‘well-heeled’, ‘down at heel’) amply conveys the importance of footwear as an indicator of status. ‘A lady’, said Miss Modern in 1936, ‘used to be known, and recognised as such, by her neatly-shod, well-bred feet. The young woman of to-day has not forgotten this axiom, and that tap-tap of her heels beats a tattoo of chic.’22

Shoes were regularly sent to the menders and repair costs were an important economic consideration. As with the main wardrobe purchases, it was the lower income families who had to spend proportionally more money on repairs, not just on their clothes but on their shoes as well. Lower-middle-class families were also spending twice as much proportionally of their income on shoe buying.23 However, the poor quality of cheaper shoes showed that it was a false economy. Mrs B., a 26-year-old housewife from Dorking in Surrey, explained why:

I like to spend as much as I can possibly afford on shoes. … I spend anything from 1 gn to 3 gns on a pair. The cheaper ones definitely are not an economy to me as I find that they lose their shape in about a month, while the more expensive shoes last almost for ever. My cheap shoes last six to nine months with care, but the dearer ones last easily two years and still keep their shape and to their dying day look ‘good’.24

There is no need for colour in H.M. Bateman’s cartoon since the expression on the face of the snooty butler says it all. The poor man has just realised he is wearing ‘brown in town’ – an unforgivable social solecism at the time. (Estate of H.M. Bateman)

Not even a Savile Row suit could protect the owner from comment if with it he was wearing the incorrect shoes. The most well-known faux pas of this period was that of wearing brown boots or shoes with a dark town suit – ‘never brown in town’. To wear brown for a formal occasion was to show disrespect, as had been immortalised by the 1910 music hall song ‘Brahn Boots’, later popularised by Stanley Holloway in 1940: ‘And we could ’ear the neighbours all remark/”What, ’im chief mourner? Wot a blooming lark!/”Why ’e looks more like a Bookmaker’s clerk … In brahn boots!”’25

Here is a classic example of how a seemingly innocent and necessary basic item of clothing could place the wearer in a social minefield. Similarly, there was no need for colour in H.M. Bateman’s cartoon, ‘The Wrong Shoes’, since it was clear that the mortified man lacked the savoir faire to realise that he had worn the wrong colour of shoes.26 Even in 2002 David Beckham, England’s football captain, who had recently been voted one of Britain’s best-dressed men, was criticised in the press for selecting brown shoes to be worn with blue suits for the England squad formal uniform.

Sometimes an item’s decline down the social scale can be charted as it became unacceptable to each successive social rank. An example of the occasional inevitability of the trickle-down of fashion is the theme of the 1922 Punch cartoon, ‘the downward spread of the spats habit’. The text reads that while spats had been considered ‘becoming in the case of the Chief, permissible in the junior partner and perhaps to be tolerated in a confidential clerk’, when the office boy takes to wearing them, asks Punch, ‘who knows where it will end?’27

By the late 1920s Punch associated spats with caddish behaviour using a seaside landlady in a cartoon to say, after an unsatisfactory experience with a flashily-dressed lodger, ‘A white spat may often ’ide the cloven ’oof.’28 Less than ten years later spats were included in a list of things a 23-year-old printer from Worthing particularly classed as ‘vulgar’ – a list that included lavender suits, double-breasted waistcoats, lemon kid gloves, bowler hats, and showy and prosperous-looking overcoats’.29 Once items were no longer exclusively worn by the upper classes, it was often seen as pretentious and ‘vulgar’ for someone of a lower class to wear them.

For men in particular, accessories could convey messages about sexuality. The combination of brown and suede in shoes was associated with, as Robert Graves noted, the ‘Pansy’ or ‘homosexual beauty’.30 Worn with flannel trousers since the 1920s, by the mid-1930s brown suede shoes were only just acceptable for casual wear within the middle classes. Mrs R., an undergraduate at Cambridge in the late 1930s, remembers suede shoes being controversial: ‘But I knew lots of people who did wear them. They were … I think they were probably looked down on by the dons if you know what I mean.’31

Just as for men, coloured shoes for women could be seen as social mistakes. Black was not to be worn in the country.32 During the 1930s shoes made of two tones of leather, one light, one dark, and worn by both men and women, were known as ‘divorce court’ or ‘co-respondent’ shoes. It was well known that Wallis Simpson wore them but it would have been considered extremely daring for a middle-class British girl to do the same. Mrs R., an MP’s daughter from Gloucestershire, remembers ‘two-coloured shoes, you know, they were known as co-respondent shoes, everyone knew that. I mean you wouldn’t dream of them. Or if you did, you were not quite our class dear, which was, NQOCD. Isn’t that awful? That was said sometimes.’33

HAND IN GLOVE

For women, gloves were seen as a necessity throughout the middle classes. There is no doubt that this was a hangover from the centuries-old ideals of aristocratic gentility, together with Victorian respectability when the gloved hand became the mark of a lady who had no need to work.34 From the early twentieth century the practicalities of modern living, travelling on public transport and later the increased popularity and availability of car driving, only served to emphasise the expediency of gloves for all women. In 1923 the firm of Atherton & Clothier, based in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, were producing 6,000 pairs of gloves a week, of which 200 were hand-sewn chamois gloves.35

The usefulness of gloves did nothing to lessen their importance as a social statement either. Far from becoming more democratic, gloves became a mark of social standing with spotlessly clean white kid gloves being at the top of the status tree. White gloves rarely regained their purity after washing and few women could afford the extravagance of Nancy Astor, who sent hers to the cleaners after only one wearing.36 As The Girls’ Favourite pointed out, ‘White gloves that aren’t white do spoil the general appearance of a smart girl, don’t they?’37

For the majority of women white gloves were a luxury kept for best. Female university students at Bedford College, London, had to wear white gloves with their academic dress on public occasions though there is little photographic evidence that they wore them willingly at any other time.38 For the most part, leather gloves in a variety of more practical colours were the accepted choice. Woollen gloves were not acceptable other than for sporting or country wear. ‘Good gloves, nicely fitted, are the best economy in all ways, for neatness and daintiness in detail are the primary considerations that must be ever present in the mind of all women striving towards Success through Dress!’39

Not surprisingly, Mass-Observation found in 1939 that gloves were worn less by younger women than by those over thirty who did not work, suggesting that it was older women who were anxious to utilise this symbol of gentility.40 Gloves were put on before leaving the house but few women went to the extremes of a schoolmaster’s wife in 1924 who retained the Victorian habit of keeping her gloves on when visiting for tea.41 Nevertheless, gloves were seen as ‘the hall-marks of refined apparel’.42 The girls of the Merchant Taylors’ School in Crosby, for example, were told they must wear their gloves on the way home ‘so as not to be mistaken for council school children’.43

The necessity for gloves had certainly not lessened by the end of the 1930s. Even the reduction of hat-wearing did not diminish the popularity of gloves for women. Glove historian C. Cody Collins has attempted to explain why this was so. ‘Gloves’, Collins stated in 1947, are ‘of paramount importance to that instinctive feeling of a completed costume and are a signature of social standards.’44 In a list of hat and glove purchases in Bolton in 1939, some women are listed as not wearing hats but there is no such entry for gloves.45 Gloves were an integral part of any outfit and it was desirable that they matched other accessories such as shoes and bags.

With the need not just for quantity but also for quality in gloves, they were listed as often being given or received as presents.46 In 1934 gloves were advertised at Christmas as ‘gifts that are absolutely certain of success’.47 The majority of female Mass-Observation respondents wore gloves year round for going out of the house, some even for work.48 A teenage student from Romford, Essex, who admitted she did not wear them, says that most of her friends did because they did not feel dressed without them.49 Gloves were not always worn willingly, however. The feeling among many Mass-Observation respondents was that one had to wear them otherwise other people would think one was not ‘dressed’.50 As with hats, the idea that gloves were an essential social accessory for women was still widespread well into the 1950s.51

HATS OFF!

In contrast, the choosing and wearing of hats initially did not seem so fraught with anxiety and social brinkmanship. Indeed, the most common visual cliché of the interwar years is the inevitability of hat-wearing among both men and women. It is presumed that men of all classes willingly wore hats whenever they were out of doors, whether it was a trilby, a top hat or a flat cap. But since the eighteenth century and before, men’s hats had been part of a code of etiquette unique to an item of clothing.52

Hats were still seen as an essential prop of street etiquette for the man from the middle and upper classes who cared about decorum. To fail to acknowledge status distinctions by dress and gesture was disrespectful, and therefore anathema to the respectable persona so many of them were trying to present. Young men brought up in an upper-middle-class family would have been initiated into the complicated rituals of hat lifting from their youth.

For those less sure of the social rites involved, there was no shortage of published advice. The following extract published in 1937 shows by its length how complicated the rituals were to those unsure of themselves. While hat honour may have been second nature to many men, to the uninitiated it was a social minefield:

It is not necessary for you to raise your hat if you see a lady of your acquaintance in a public vehicle in which you are also a passenger. A little smile or nod is sufficient. Otherwise, you should always raise your hat when meeting a lady whom you know. If the lady is a close friend, raise your hat immediately she gets near; but if you do not know her very well, you should wait until she acknowledges your presence before raising your hat. You should also raise your hat when meeting a male friend accompanied by a lady, whether you know the lady or not, when walking with a lady who meets someone she knows, and when walking with a man who has occasion to raise his hat. To raise one’s hat, however, does not constitute an introduction. If, for example, when walking with a friend you meet an acquaintance of his and raise your hat, you should make no sign if you meet the lady again when alone – unless she should happen to smile or bow. … While there is no need for a sweeping movement like that of the cavalier of other days, do not go to the other extreme and simply touch the brim with your forefinger, as many men have a habit of doing in these days. Raise the hat just clear of the head for a moment, that is the correct procedure.53

It comes as no surprise that this is taken from a revised version of an etiquette manual for men first published in 1902. What is surprising is that while changes had been made to various other sections, this particular section remained essentially the same from 1902 to 1937.

It was a recognised problem that the man who went hatless was in danger of not being able to ‘make his most courteous gesture to a woman’. Writing to The Times in 1934 under the heading ‘Polite Though Hatless’, Mr Roberts of Bristol was ‘unrepentant about [his] sartorial deficiency’ but anxious to find an alternative gesture of courtesy.54 A reply from Mr Stuart Jervis of London suggested such an alternative:

I have been hatless for years … I used to smile (I hope) charmingly, and incline my head, in what I can only describe as a lingering, and slightly fond, manner. The success almost dazzled me. I could almost hear the ladies say, “Ah! An eccentric. But what manners.” But now (eheu fugaces) [Alas! Our fleeting years pass away] I am older, still hatless, and rather fat. But the method still works. A smile, an inclination of the head, … at least I am not mistaken for a Fascist by the passers-by.55

The debate on hatlessness centred on etiquette. The confusion of a vicar from Moretonhampstead exposed the complications of hat lore in the pages of The Times in 1929. It shows that not only was hat honour directed at women but also that there was a complicated hierarchy of professional men to be acknowledged as well:

I cannot keep my hat on in a bank, though I know my courtesy is often mistaken by my young friends for eccentricity, not to say insanity. It dates from my undergraduate days at Oxford, when none but a ‘bounder’ would have done it. The reason, as I understood it, was that a banker is not a tradesman but a professional man. Even now I suppose, hats come off in a doctor’s consulting room, or a lawyer’s office. What has the poor banker done, that he should be insulted?56

It is not surprising that the older generation were reluctant to give up wearing a hat, while the less deferential younger generation were more relaxed about it. After the First World War there was an anxiety in the industry that men were leaving off their hats in an effort to appear more relaxed.57 There was a mild resurgence in hat-wearing in the late 1920s, caused mainly by the variety of hats now needed to suit different social occasions. For the majority of middle-aged men one or two hats would have been all they needed – or wanted. Some men, said the Hatter’s Gazette, were ‘so conservative in their tastes that they would dread the change from a bowler to a soft felt as they would dread the migration from their native haunts to an unexplored territory’.58

Newspaper photographs from the 1920s and 1930s suggest that the majority of men wore hats of varying styles whenever they were out of doors. Yet closer inspection reveals another story. By the end of the 1920s there were already murmurs of discontent among the hatting trade that ‘hatlessness’ was again affecting their business. Such was the concern that hat manufacturers and wholesalers refused to see travelling salesmen who were hatless.59 Among the trade journals, retailers were shown medical propaganda from America, which was intended to be sent to schools, pointing out the supposed health risks of going hatless.

The trade suspected that the hatless movement was led by a younger generation not willing to follow the formality of their fathers. They also tried to suggest that hatless men were ‘inclined towards loose morality, criminal tendencies, suicide and revolutionary activity’.60 Since this was at a time when the Men’s Dress Reform Party was saying that hat-wearing was unhealthy, it was not difficult for the trade press to point out the eccentricity of the MDRP to further its own cause.

In addition, there were regular debates in the trade press on the correct way to tilt one’s hat, if at all. The tilt at which a man wore his hat was of consequence. Commenting on the film Cavalcade, made in America but supposedly set in Britain, a correspondent to The Times said the film’s one flaw was the men’s hats, especially in the crowd scenes, since ‘Englishmen don’t wear their hats like that.’61 Pushed over to the right, the wearer looked like ‘a rowdy’ or someone ‘presiding at a coconut shy’. Tilted back, one could look like ‘Mr Alfred Jones, of Peckham, in a punt with his braces on,’ or in other words like a working-class man at leisure. The worst was to tilt to the left when one would lose ‘social status completely [and] become a mental deficient’.62

The main worry for the hat trade was obviously that many men were disregarding etiquette altogether and leaving off hats. In an article in Punch entitled ‘My Hat!’, the author confessed to hating hats. While he could see they had their uses in wartime, ‘in the civilised times of peace it cannot be denied that the principal end of a gentleman’s hat is to be taken off to ladies’.63 This, he felt, could not justify the prolonged use of an item of clothing.

A more fortuitous linkage was the one that developed between the cinema and the hat industry. Battersby’s, leading men’s hat manufacturers, realised that the ‘hatless’ problem was coming from the younger generation. ‘The hat Father wants is not the one that his son is likely to wear,’ they claimed.64 The customer they were losing was the sixteen-to-twenty-five year old whose ‘principal form of relaxation [was] taking his girl to the “talkies”, and without his hat he [felt] sporty and bold, and perhaps a bit dashing’.65 This young man, they assumed, identified with the characters he admired on the screen – ‘perhaps, that exclusive product of Hollywood, the “Tough Guy”’. In response to this, Battersby’s produced a lower priced hat called the ‘Big Shot’. To judge from the press coverage, the hat appears to have been a success, selling 100,000 in eight months.66 The ‘Big Shot’ was followed by the ‘Tiger Rag’ named after the bandleader Harry Roy, and then the ‘Alex James’.67

With hat sales falling in the early 1930s, the hat trade was grateful for the opportunity to promote hat-wearing through film star role models such as Paul Muni. (Hulton Getty)

Nevertheless, it was still an uphill struggle to persuade young men to buy these hats since many of them were rejecting not just the styling of hats but also the hat etiquette followed by their fathers. It is significant that hats such as the ‘Big Shot’ were aimed at the young or working man from the lower middle classes. The more solid older man would have shunned such a raffish look as bordering on the ‘spiv’, on a par with the brown bowlers worn by ‘street-corner bookmakers’.68 Instead, the trade press tried to appeal to a man’s dignity by pointing out the status he might lose by going out hatless. For example, if a man did not keep his hat on in a department store, claimed the Manchester Evening Chronicle, he was in danger of being mistaken for a floor walker.69 Men’s Wear Organiser used the accusation of meanness to try to shame men into buying a new hat to replace one that perhaps they had used for anything up to twenty years.70

In 1935, in an effort to attract publicity, a hatting firm in Luton – the ‘boater borough’ – invited French film star Maurice Chevalier, known for wearing straw hats, to the town to receive a donation of presentation boaters. The visit was a huge success in terms of publicity since thousands of town residents, many of whom would have worked locally in the hatting industry, turned out to see him.71 However, a photograph of the crowd shows that even in this hatting town at least half the men, mainly young, are not wearing hats.

By 1939 the hat trade had to try harder than ever to maintain sales by pursuing blatant links with the cinema. ‘Tie Up with the Films’ headlined a feature in the Hatter’s Gazette showing photographs of Adolphe Menjou and other well-known actors wearing various styles of soft-brimmed hats.72 They were fighting a losing battle against the tide of men who preferred to be hatless whether for expense, status or fashion. The decline of hat-wearing is confirmed by the attitude of the respondents of the Mass-Observation directives. It is hard to find a man who has something positive to say about wearing hats. Conversely, they are eager and proud to state that they do not wear a hat at all, except for two men who only wore one in the rain.73 Hatlessness was becoming a sign of male daring.

The Hatter’s Gazette was right to be concerned since informal head-count surveys during a snowstorm in London in January 1939 show that 23 per cent of the men seen were hatless. Perhaps even more surprising were the results of similar surveys from the hatting centres of the north of England. Male hatlessness was at 14 per cent in Stockport and 20 per cent in Manchester.74 A final blow came when the War Office issued a photograph of a hatless man in July 1939 representing the militiaman’s off-duty uniform.75 Under the heading, ‘Were they going to send them out like this?’, the hat trade complained bitterly. As an afterthought, the War Office, somewhat surprisingly, added a beret to the outfit. However, the damage had already been done and hat-wearing would never return to the levels of the 1920s.

A FEATHER IN HER CAP

The trade in women’s hats in contrast was robust between the wars, millinery still being a high-fashion accessory. The relatively low cost of a hat compared with that of the complete outfit allowed women to update their look for a moderate expenditure. The popularity of women’s hats waxed and waned depending on hairstyles. In 1926 the Luton News claimed the town, the centre of Britain’s hat-making industry, had been ‘made rich by shingling’. The need for a pull-on hat that did not have to be pinned had ‘banished unemployment from Luton’.76 Removing hats in public, however, meant exposing squashed or untidy hair. Such exposures were especially tricky for middle-class women involved in public speaking:

Some of the early Labour women leaders, and particularly the younger generation of bobbed-headed enthusiasts, solved the hat question economically. Their first act on mounting a platform was to discard their headgear. Many of the advanced feminists also follow this practice. Some, for instance, even in a public restaurant at lunch-time, almost invariably remove their hats. The ‘hatless’ vogue on the platform, of course, involves additional care of the coiffure. … The platform speaker can gain assurance by the knowledge that she is wearing the correct hat.77

Most women solved the squashed-hair problem by not removing their hats in public places. However, in general women were not subject to the same demanding hat etiquette as men. Women’s hats did not have to be removed for any social acknowledgements and generally remained in place once they were outside and in public places such as shops and tearooms.

Women’s hat-buying habits were the constant butt of jokes but hats were a relatively cheap way of enlivening much-worn outfits and remained a popular accessory for women until after the Second World War. (Punch, 13 October 1937 © Punch Ltd)

How to cope with hats was to prove an issue for the first female Members of Parliament. Male MPs were not allowed to wear hats inside the House of Commons unless they wished to make a point of order, although they needed to have one with them to reserve their seat. Female MPs were exempt from the rule such was the almost biblical strength of feeling that women ought to have their heads covered on public occasions.

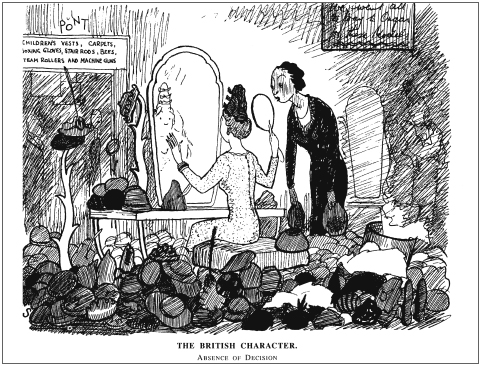

Women’s supposedly frivolous attitude to hats was the constant butt of cartoons. While acknowledged as a social necessity, hats appeared to incorporate all the weaknesses of the female gender: extravagance, frivolity and indecision. Some women regarded hats not as something frivolous but as a necessity which was often a nuisance to buy. A politician’s daughter from Gloucestershire only ever wore the one hat she owned in London and never during her time as an undergraduate at Cambridge.78

Gloves and hats were vital social accessories for women throughout the interwar period. However, while hats remained firmly in place during social outings, it was increasingly unusual to keep one’s gloves on indoors although they would always be close at hand. (Hulton Getty)

There appears to have been a more relaxed atmosphere at Cambridge, in contrast to the all-female Bedford College in the heart of London’s Regent’s Park, where students were not allowed to leave the college grounds without a hat.79 A non-hat-wearing school teacher in 1930 was warned that she would not be recommended for promotion unless she took to wearing a hat. With the scarcity of jobs, she resigned herself to knitting a tam o’shanter to wear.80 A 37-year-old nurse from Chester admits buying one hat that suited her for winter and wearing it ‘until it drops to bits’.81

These women’s rates of hat buying were well below average since according to Mass-Observation by 1939 ‘Mrs Everywoman’ was buying 2.7 hats a year.82 The Daily Mail doubled this figure, telling its readers that ‘five times a year (on average) every wife goes home with a smile and hatbox in the hope of pleasantly surprising her husband with the honeyed words, “Do you like me in this model, dear?”’ The paper acknowledged that there was a percentage of what manufacturers termed ‘open air’ girls who did not wear hats except on special occasions. ‘This habit (or lack of habit)’ was said to be on the increase especially in the north of England, for some unexplained reason. The hat trade did not, the paper said, regard this as widespread enough to be menacing.83

However, by the mid-1930s the press local to the centre of the hat-manufacturing trade in Luton were giving the clear impression that it was a problem. Hatting factories posted notices requiring all employees to enter the premises wearing some form of headgear. ‘We weren’t allowed in the factory without a hat on – take it off when you get round the corner maybe – but you had to wear a hat … it was just as simple as that.’84

The older generation of women remained solidly loyal to everyday hat-wearing until well into the 1950s.85 Indeed, it was one of the last vestiges of pre-war respectability to disappear, along with the City gentleman’s rolled umbrella and bowler hat.